Rep:Mod:lebg

Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

Molecular mechanics is a useful modelling technique which relies solely on classical physics. More specifically, this means that Newtonian physics are applied to atoms in molecules. Since we know that Newtonian mechanics cannot describe accurately the atomic world, we need to start by making assumptions about the microscopic objects we will be dealing with. The first of these approximations is that each atom is assumed to be a particle with a fixed radius (the Van der Waals radius), polarisability and charge, whose linkage to other atoms of the molecule is characterised by a bond which has an associated force constant. Classical physics fails to predict force constants and equilibrium bond lengths and as such the values used within the model are ones that were determined experimentally. Moreover, the bonds between atoms are modelled using Hooke's law, which states that the restraining force exerted by a bond is proportional to the displacement from the equilibrium bond length. As we shall see in this section, this quite rough model can be a very useful first approximation to study the reactivity and thermodynamics of molecules.

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene and Hydrogenation of the Endo-Product

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

It is a well known fact that at room temperature, the spontaneous dimerisation of cyclopentadiene leads to the formation of the endo-product.

It seems natural to want to rationalise this selective dimerisation via modelling methods. One way to do this is to compute the relative energies of the exo- and endo-dimers, which can be done fairly quickly using the MM2 calculations which are supported by Chembio 3D. We will then be able to compare the relative energies of the two dihydro-derivatives -again using MM2 calculations- to predict which of the two products is more stable, in a thermodynamic sense.

It is found that the energy of dimer 1 is of 31.89 kcal/mol, whereas that of dimer 2 is of 34.00 kcal/mol. Hence, we can say that dimer 1 is thermodynamically more stable than dimer 2. This observation -which disagrees with the experimental observation that dimer 2 is formed preferentially- suggests the idea that the latter is the kinetic product, and thus that this dimerisation is under kinetic control. This is consistent with experimental observations [1].

Hydrogenation of the Endo-Product

We have seen that MM2 calculations are a quick way of determining the relative energies (and hence stability) of a pair of isomers. The approach presented above can also be used to rationalise the selectivity of the following reaction. It has been reported that hydrogenation of the endo-dimer 2 leads to the selective formation of dihydro-derivative 4 shown in the reaction scheme below, although at first glance it is not evident why one would selectively be formed over the other. Note that only prolonged hydrogenation of dimer 2 affords the fully reduced product[2].

Two reasons can be put forward to explain the observed selectivity: one of the alkene bonds is more reactive than the other and/or one of the two products is more stable than the other. Running MM2 calculations will allow us to determine which of the two dihydro-derivatives is more stable, from a thermodynamic point of view.

Let us analyse how the relative contributions from the stretching, bending, torsion, Van Der Waals and hydrogen-bonding energy terms contribute to the total energies of dihydro-derivatives 3 and 4. The results are summarised in the table below.

| Molecule | Stretching energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Bending energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Torsion energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Van Der Waals energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonding energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Total energy /(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product 3 | 1.24 | 18.97 | 12.15 | 5.73 | 0.16 | 35.93 |

| Product 4 | 1.10 | 14.54 | 12.50 | 4.51 | 0.14 | 31.15 |

Hence, we can see that product 4 is more stable than product 3 by approximately 4 kcal/mol, which tells us that the former is the thermodynamically favoured product.

It should be noted that although the stretching, torsion and hydrogen bonding energy contributions are roughly similar in both molecules, the bending energy contribution of product 4 is nearly 3.5 kcal/mol lower than that of product 3. Indeed, we know that norbornenes experience -due to the presence of a bridgehead carbon- considerable ring-strain and are consequently very reactive (for example, they undergo ring-opening polymerisations very readily[3]). On the other hand, cyclopentene rings are much more stable since they do not experience the ring strain caused by the presence of a bridgehead carbon. This explains why product 3 is much more strained than 4, and hence why the former is less thermodynamically stable. Since experimental observations tell us that the thermodynamically more stable product is formed during the course of this reaction, we can conclude that the reaction is under thermodynamic control. Note that in this specific example, another reason for the observed selectivity (but which comes this time from a kinetic argument) is that the norbornene alkene bond is more reactive than the cyclopentene one, and hence we can suspect that even under kinetic control the reaction would still afford product 4.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Additions to Pyridinium Ring Derivatives

Addition of a Grignard reagent to a derivative of prolinol

From purely mechanistic considerations, we could postulate that addition of a Grignard reagent to the following pyridinium derivative shown below would give the following racemic product.

This prediction, however, is not consistent with experimental observations. Indeed, it was reported that the reaction is in fact stereospecific, and that the isomer shown below is formed preferentially[3].

Using MM2 calculations, and focusing particularly on the angle of the carbonyl group with respect to the aromatic ring, we shall try to rationalise the enantiospecificity of this reaction. As alluded to in the mechanism shown previously, the carbonyl oxygen coordinates to the magnesium centre of the Grignard reagent, and thus the angle between the carbonyl group and the plane of the aromatic ring should be studied if we observe that the methyl delivery occurs preferentially from one of the faces of the aromatic ring.

The energy of the molecule was computed for a range of dihedral angles, and the results are plotted in the graph below.

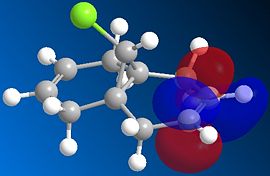

We can see that an angle of 11.3° gives the most stable conformation (relative energy of 43.13 kcal/mol). In that conformation, the carbonyl oxygen sits above the plane of the aromatic ring and thus the coordinated magnesium will also have to sit above the plane of the ring. This in turn means the attacking methyl will be above the plane of the ring, which explains why it will attack preferentially from that side of the ring. A 3D representation of the initial molecule in its lowest energy conformation is shown below.

|

Addition of aniline to a pyridinium ring

Another interesting reaction, which is somewhat related to the one presented above, is the addition of aniline to the following pyridinium derivative. The mechanism itself is fairly straightforward, as shown below, and one could expect the product to be racemic.

As in the previous example, the mere mechanistic considerations do not allow us to predict the experimental observation, which is that one of the enantiomers is formed preferentially[4] (the favoured product is shown below).

A closer look at the structure of the molecule shows that the carbonyl group is close to the site of attack; this hints at the fact that the latter might be sterically shielded by the former, especially in this case where the nucleophile is bulky. Hence, we can postulate that the angle between the pyridinium ring and the carbonyl group might be playing an important role in dictating the stereochemistry of the product. To investigate this further, we shall follow the same approach as previously and compute the energy of the starting molecule for a range of dihedral angles, using MM2 calculations. The results are summarised in the plot below.

We can see that the relative energy of the molecule is at a minimum when the dihedral angle of interest is of -21 degrees (the molecule then has a relative energy of 63.38 kcal/mol). A 3D representation of this molecule in its lowest energy conformation is shown below.

|

The fact that the carbonyl group is sitting below the plane of the molecule tells us that attack of the bulky nucleophile will, for steric reasons, have to occur from the other face of the pyridinium ring, which explains the enantioselectivity of the reaction.

Stereochemistry and reactivity of an intermediate in the synthesis of taxol

One of the two molecules shown below is an intermediate in the synthesis reported by Paquette of the anti-cancer drug Taxol[5]. It is observed that the intermediate initially synthesised spontaneously converts to its alternative isomer, which suggests that one of the two molecules has a lower energy than the other. As one can see from the structures shown below, it is the ring-flipping of the ten-membered ring which allows the carbonyl group to point "up" or "down" (i.e. allows interconversion between the isomers). Since ring-flipping is induced by bond rotation, and that in this case such rotation is prevented by steric hindrance (as confirmed by the fact that both molecules can be isolated), we are witnessing a case of atropisomerism.

|

|

We are looking to determine which of the two atropisomers is the most stable. Shown below are the relative energies of the two molecules obtained with MM2 calculations.

| Molecule | Stretching energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Bending energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Torsion energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Van Der Waals energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonding energy contribution /(kcal/mol) | Total energy /(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atropisomer 9 | 2.68 | 15.84 | 18.21 | 12.64 | 0.15 | 48.87 |

| Atropisomer 10 | 2.56 | 10.68 | 19.60 | 12.54 | -0.18 | 44.32 |

We observe that 10 has a significantly lower energy than 9 (by approximately 4.5 kcal/mol). Thus we can conclude that atropisomer 9 was initially synthesised, but that upon standing it spontaneously converted to 10, which is the more stable form. It should be pointed out that the bending energy contribution makes up for most of the total energy difference between the two isomers, which shows how much more strained atropisomer 9 is when compared to atropisomer 10.

An interesting feature of isomer 10 is that the alkene moiety is surprisingly unreactive when comapared with common alkene functions. This can be rationalised by invoking the concept of alkene hyperstability[6], which tells us that some alkenes actually experience less strain (and are therefore more stable) than their saturated counterparts.

As observed in the 3D representations of the saturated analogues of 9 and 10 (respectively 9' and 10'), having sp3 hybridised carbons and concurrently bond angles of 109.5 degree induces more strain in the ring system. This is confirmed by MM2 calculations, which show that 9' and 10' both have an energy 53.19 kcal/mol, which is significantly higher than the energies of 9 and 10, confirming the hypothesis of alkene hyperstability. Hence, we can see how a typical alkene reaction which involves reduction of the moiety (such as hydrogenation) would be thermodynamically unfavourable with those two species.

|

|

Modelling using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Introduction

In the previous examples, our rationalisations of the reactivity and selectivity of the chemical reactions studied relied solely on molecular mechanics calculations. This approach, although very useful in some respects, is mainly focused on steric effects and tells us very little about electronic effects. We shall now focus our attention on examples where electronic effects dictate the outcome of reactions, and whose study require computation of the molecular orbitals involved. We shall also see how taking the molecule's electrons into account allows us to predict spectroscopic properties. In this example, we will use the MM2 method to optimise the geometry and energy of the systems, and the MOPAC/PM6 method to generate an approximate representation of the molecular wavefunction.

Regioselectivity of a dichlorocarbene addition

We shall try to rationalise the unusual reactivity of molecule 12 (structure shown below) using an orbital approach.

Indeed, it is observed that this molecule, when reacted with dichlorocarbene, has an alkene moiety which is significantly more reactive than the other, as shown in the reaction scheme below.

It should be noted that the sp2-hybridised carbon centre of dichlorocarbene has an empty p-orbital as well as a full sp2 orbital which contains a lone pair (that is, dichlorocarbene is a singlet carbene, as opposed to a triplet carbene which would have both of these orbitals half-filled). This means that this reagent both acts a Lewis acid and as a Lewis base. During the reaction, the electron-rich alkene function starts by putting electron density in the empty p-orbital of dichlorocarbene. The fact that only one of the two alkene bonds reacts with dichlorocarbene suggests that one of the two is more electron-rich than the other. To investigate this, we shall have a look at the valence-electron molecular wavefunctions of the HOMO. Indeed, we know that most of the chemical reactivity of a nucleophilic molecule is mainly dictated by the energy and shape of the HOMO, while the reactivity of an electrophile is largely governed by the properties of the LUMO.

The HOMO (left) and LUMO (right) of the starting bicyclic structure are shown below.

|

|

This shows clearly that there is more electron density associated with the alkene bond which is on the same side as the chlorine atom (the syn-alkene), which means that this bond is more nucleophilic. Hence, we can infer from those MO calculations that dichlorocarbene will react preferentially with the syn-alkene moiety to form the substituted cyclopropane structure, which is indeed consistent with experimental observations.

Influence of the C-Cl bond on the vibrational frequencies of 12

To investigate this, we shall compare the vibrational frequencies of 12 and one of its hydrogenated derivatives 13, whose structure is shown below.

In this example, we use the density functional approach to obtain the vibrations of the two systems. To do this, we first optimise the geometry of both molecules using MM2 calculations, and the resulting Gaussian Input File is edited so that the top line shows:

# b3lyp/6-31G(d,p) opt freq

Essentially, this means that the geometry of the molecules will be optimised with the b3lyp method and using the 6-31G(d,p) basis set. The resulting .gjf file is submitted to the SCAN suite for optimisation, and the returned data can be visualised in Gaussview.

The major vibrations (i.e. the alkene C=C stretches and C-Cl stretch) of 12 and 13 are tabulated below.

| Molecule | Syn-alkene C=C stretch/(cm-1) | Anti-alkene C=C stretch/(cm-1) | C-Cl stretch/(cm-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diene 12 | 1757 | 1737 | 770.9 |

| Alkene 13 | 1758 | N/A | 775.0 |

It should first be mentioned that for both molecules, the predicted frequencies for the carbon-chlorine bond stretching vibration agree well with the 780 cm-1 reported in literature[7]. On the other hand, the alkene stretching frequencies reported in literature[8] (1620-1680 cm-1) are much lower than those predicted by the density functional approach. This is due to the fact that stretching frequencies predicted using the method mentioned above are systematically higher than the actual stretching frequencies by a factor of approximately 8 % (this error will be revisited in the analysis of the IR spectra carried out in the Mini-Project below). Indeed, accounting for this error would give us a predicted stretching frequency of 1616 cm-1 for the syn-alkene, and of 1598 cm-1 for the predicted stretching frequencies of the anti-alkene. These values are, as expected, much closer to the literature values.

Next, we notice that in diene 12, the syn-alkene bond has a higher stretching frequency than its anti-counterpart. This implies that the syn-alkene bond is stronger (more energy is needed to make it vibrate), and hence we could infer that it is less reactive. This does not agree with the MO calculations or experimental observations reported above, which suggest that the syn-alkene bond is more reactive. This contradiction can nonetheless be resolved by noting that in an electrophilic addition, the localisation of the most reactive electrons (i.e. those of the HOMO) is more important than the strength of the two potentially reactive bonds. That is, of course, providing that the difference between the strength of the two bonds isn't too large (such as in this case, where this difference is of 20 cm-1).

Finally, we observe that the syn-alkene stretching frequency in both 12 and 13 are nearly identical (1757 versus 1758 cm-1, respectively), which shows that the presence (or absence) of the anti-alkene bond does not really affect the strength of the syn-alkene bond.

Structure-based Mini-Project

In this section, we shall focus our attention on the work of Hu et al., whose group designed and carried out a synthesis of (+)-steviamine 14 and 5-epi-(+)-steviamine 15 which are, respectively, enantiomer and C5-epimer of the naturally occurring (-)-steviamine[9]. These two derivatives were initially synthesised because of the interest generated by the enzyme-inhibiting properties of (-)-steviamine, which have potential applications in the field of medicinal chemistry. The reaction scheme reported in the article is shown in the figure below.

As one can imagine, the ability of the group to synthesise a stereochemically pure compound and to successfully characterise it were a crucial prerequisite to the study of its pharmacology. Being able to predict the spectroscopic properties of such target molecules can prove extremely useful in their characterisation, and this is what we shall attempt in this mini-project.

The group managed to separate the two products and both of them were analysed using standard characterisation techniques, namely 13C, 1H NMR and IR spectroscopy.

In a first step, we shall predict the 13C NMR spectra of the two isomers and compare them with the ones reported in literature.

Prediction and analysis of the 13C NMR spectra of isomers 14 and 15

To begin with, the two molecules were sketched in ChemBio 3D, and their energy was minimized using the MM2 method. Shown below are 3D representations of the lowest energy conformations that I could model with that level of theory.

|

|

Note that at this stage, the relative energy of isomer 14 was of 21.42 kcal/mol, while that of isomer 15 was of 26.91 kcal/mol. This difference in stability is quite hard to foresee when looking at 2D representations of the isomers, but becomes quite obvious when one looks at their 3D representations. Indeed, we observe that in isomer 14, the methyl group lies above the plane of the bicyclic structure, while the CH2-OH group lies below it. On the other hand, in isomer 15, both the methyl and CH2-OH groups groups lie below the plane of the ring. This is a source of steric hindrance which causes the overall energy of the molecule to rise by approximately 5 kcal/mol.

Next, a molecule input file was created for both molecules and the mpw1pw91 DFT method was used, along with the 6-31G(d,p) basis set. The resulting Gaussian Input File's top line was edited so that it looked like the following:

# mpw1pw91/6-31g(d,p) opt(maxcycle=25)

These files were then submitted to the SCAN suite so as to optimise the geometry of the two molecules. When the geometry of both molecules had been optimised, the returned .gjf file was edited so that the top line showed:

# mpw1pw91/6-31(d,p) NMR scrf(cpcm,solvent=water)

This was then re-submitted to the SCAN suite but this time for NMR prediction. Note that the solvent used for the prediction is deuterated water, since the 13C NMR spectra reported by Hu et al. were both carried out in that solvent. The numbering of the carbon atoms which will be used for the rest of this section is the one showed in the structure below.

The table below summarises the 13C NMR data reported in the article for isomer 14, as well as the NMR spectrum predicted by Gaussview.

| Carbon atom | Literature shift isomer 14/ppm | Calculated shift isomer 14/ppm | Difference between literature and calculated shifts/ppm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 73.24 | 74.68 | -1.44 |

| 4 | 68.74 | 68.96 | -0.22 |

| 2 | 66.65 | 68.38 | -1.73 |

| 1 | 60.87 | 64.51 | -3.64 |

| 13 | 56.18 | 57.10 | -0.92 |

| 9 | 53.24 | 52.47 | 0.77 |

| 8 | 32.16 | 34.55 | -2.39 |

| 6 | 28.12 | 31.63 | -3.51 |

| 7 | 22.97 | 25.55 | -2.58 |

| 10 | 18.72 | 22.30 | -3.58 |

Full set of data for this spectrum available at DOI:10042/to-7409 .

Another point that needs mentioning is that the Gaussian program did not have a pre-loaded module which allows to adjust the NMR shifts for a deuterated water solvent and hence the peaks were visualised as if the spectrum had been run in chloroform. The error associated with this should nonetheless be negligible, since switching between the two solvents doesn't shift the peaks by much more than 1 ppm in most cases, and the error associated with the predicted 13C NMR shifts are of approximately 5 ppm anyway.

From the data presented above, we can say that the predicted NMR spectrum for isomer 14 agrees fairly well with the one reported in literature, the largest difference -in absolute value- between the predicted and literature shifts being of 3.64 ppm. The NMR assignment proposed by Gaussview seems reasonable, and it allows us to assign the peaks that were reported in literature to their associated nuclei (the authors of the journal did not bother reporting their assignment of the peaks). Hence, we can see that this relatively simple modelling experiment has proved very useful since it allows us to complement the data reported in literature.

Another interesting feature of the table above is that the differences between the literature and the predicted shifts are negative for all but one of the peaks. This could be due to the fact that the predicted NMR shifts are given relative to TMS in chloroform, and not in water. We could infer from this that NMR peaks usually show up at lower chemical shifts when water is used as the solvent, instead of chloroform.

Let us now compare the 13C NMR spectrum reported in literature for isomer 15 with the one predicted by Gaussview using the method mentioned previously. The results are summarised in the table below.

| Carbon atom | Literature shift isomer 15/ppm | Calculated shift isomer 15/ppm | Difference between literature and calculated shifts/ppm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 70.37 | 78.77 | -8.40 |

| 2 | 69.59 | 71.37 | -1.78 |

| 1 | 66.58 | 66.12 | 0.46 |

| 13 | 60.10 | 63.39 | -3.29 |

| 4 | 58.84 | 55.89 | 2.95 |

| 9 | 55.48 | 48.80 | 6.68 |

| 8 | 31.55 | 33.56 | -2.01 |

| 6 | 22.50 | 31.72 | -9.22 |

| 7 | 19.89 | 20.48 | -0.59 |

| 10 | 17.70 | 17.06 | 0.64 |

Full set of data for this spectrum available at DOI:10042/to-7408 .

It is quite obvious from the table above that the NMR prediction wasn't as successful for this isomer, as we observe that for some peaks the difference between the predicted shifts and those reported in literature can be as high as 9.2 ppm (in absolute value).

By inspection of the chemical shifts reported in literature, we can see that the only peak which would allow us to clearly distinguish between the spectra of the two isomers is the third most shielded peak, which is assigned to carbon-6 in both compounds. Indeed, carbon-6 has a chemical shift of 28.12 ppm in isomer 14 but a chemical shift of 22.50 in isomer 15. This is the only peak for which the difference between the two literature shifts is superior to the error of approximately 5 ppm associated with NMR spectra predicted using this method. Unfortunately, it appears that our NMR prediction is most inaccurate (9.2 ppm difference between the predicted and literature shifts) for this precise peak. This inaccuracy prevents us from really being able to distinguish between the two compounds from their spectra.

Furthermore, we should expect the relative assignment of the peaks for isomer 14 and 15 to be the same even if the chemical shifts aren't exactly similar, since the two molecules are nearly identical in structure. This is not observed, and a plausible origin to this and the aforementioned discrepancy is the optimised geometry of the molecule which was returned by Gaussian and submitted to the same program for NMR prediction.

Comparison of the two optimised geometries returned by Gaussian show that the conformation of the five-membered ring in the two isomers is different (see below). Indeed, we observe that for isomer 14, carbon-2 lies well above the plane of the ring whereas the same carbon is more in-plane for isomer 15.

|

|

One should bear in mind that the NMR predictions returned by Gaussian only apply to the precise conformation which was initially submitted, whereas an actual NMR spectrum is effectively a time-average of all the possible conformations of the molecule. This means that, providing one of the conformations of the molecule is sufficiently more stable than the other ones (i.e. providing the molecule spends most of its time in one conformation) and providing the lowest energy conformation was submitted to Gaussian, the predicted spectrum obtained will agree fairly well with the experimental one (see the predicted NMR spectrum for isomer 14). However, if one does not submit the lowest energy conformation to the program for NMR prediction (as it is suspected for isomer 15), then large discrepancies will be observed between the predicted and experimental spectra.

In an attempt to get a more accurate spectrum for isomer 15, the geometry optimisation process was repeated (carbon-2 was pushed above the plane of the five-membered ring as much as the preliminary MM2 optimisations would allow) and the returned geometry was submitted for NMR prediction. Shown below is the geometry that was returned by Gaussian. As one can see, the conformation of the five-membered ring hasn't really changed, but one feature to notice is the change of orientation of the alcohol group bonded to carbon-13, with the alcohol hydrogen pointing towards the other hydroxyl group, and thus favouring hydrogen-bonding interactions.

The results obtained with the newly optimised geometry are summarised in the table below.

| Carbon atom | Literature shift isomer 15/ppm | Calculated shift isomer 15, re-optimised geometry/ppm | Difference between literature and calculated shifts/ppm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 70.37 | 78.99 | -8.62 |

| 2 | 69.59 | 74.97 | -5.38 |

| 1 | 66.58 | 63.24 | 3.34 |

| 13 | 60.10 | 61.58 | -1.48 |

| 4 | 58.84 | 57.03 | 1.81 |

| 9 | 55.48 | 47.73 | 7.75 |

| 8 | 31.55 | 32.34 | -0.79 |

| 6 | 22.50 | 32.29 | -9.79 |

| 7 | 19.89 | 19.92 | -0.03 |

| 10 | 17.70 | 14.63 | 3.07 |

Full set of data for this spectrum available at DOI:10042/to-7407 .

Unfortunately, we observe that the differences between the predicted and literature shifts are roughly similar to those calculated previously for this same isomer. As a consequence, analysis of the predicted spectra does not really allow us to distinguish the two isomers. We have to conclude that this discrepancy is either due to the fact that the GIAO method is unable to predict an accurate spectrum for this molecule (this seems unlikely since the one predicted for the other isomer agreed reasonably well with literature spectra) or to the fact that the geometry of this molecule could not be optimised to its most stable form. Since the predicted NMR spectrum for isomer 14 matches much more closely the data reported in literature, we shall assume that the assignment associated with the spectrum of isomer 14 is the correct one.

It could be suggested that a more advanced level of theory needs to be used to investigate this problem further, but this is not possible considering the time and resource limitations that are inherent to the nature of a mini-project.

Finally, it would have probably been easier to study this problem in more detail had there been more than one journal article reporting the synthesis and characterisation of these two compounds (on the Scifinder and Reaxys databases).

Analysis of the predicted vibrational spectra of isomers 14 and 15

In the data reported by Hu et al., some of the vibrational frequencies characteristic of isomers 14 and 15 are reported, but no assignment of these peaks are to be seen. In this section, we shall attempt to correlate the observed IR peaks to those predicted by a computational method, namely the b3lyp procedure coupled to the 6-31G(d,p) basis set.

More generally, both molecules were initially sketched in Chembio 3D and their geometries were optimised using MM2 calculations. Gaussian Input Files were then generated for each molecule, and those files were edited so that the first line showed:

# b3lyp/6-31G(d,p) opt freq

The resulting .gjf files were submitted to the SCAN suite for IR prediction and the returned data was visualised in Gaussview. It should be noted that the error (in wavenumbers) associated with predicted frequencies for stretching vibrations is systematically higher (by a factor of approximately 8%). Hence, all stretching frequencies were corrected in the following way:

, where is the frequency of the stretch in wavenumbers.

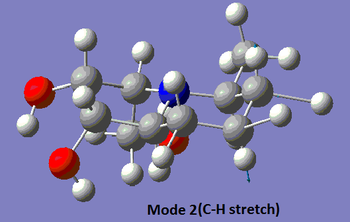

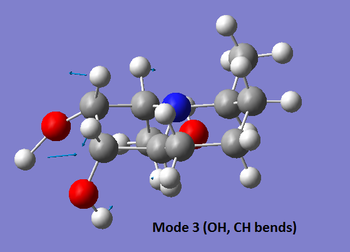

The table below summarises the data reported in literature for isomer 14 and compares it with the vibrational frequencies predicted by the aforementioned method. Note that the modes are numbered, so that the snapshots of the vibrations provided below the table can be matched to the associated frequencies.

| Mode number | Literature vibrational frequency/cm-1 (intensity) | Stretching mode | Correction applied | Predicted vibrational frequency/cm-1 (intensity), (corrected value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3366 (s) | Yes | Yes | 3681 (s), (3387) |

| 2 | 2928 (s) | Yes | Yes | 3076 (s), (3160) |

| 3 | 1441 (m) | No | No | 1440 (s), (n/a) |

| 4 | 1381 (m) | No | No | 1367 (s), (n/a) |

| 5 | 1138 (s) | No | No | 1164 (s), (n/a) |

| 6 | 1099 (s) | No | No | 1088 (m), (n/a) |

| 7 | 1038 (s) | No | No | 1044 (m), (n/a) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We observe in the predicted spectrum all of the expected vibrations, namely the OH and aliphatic CH stretches and bends. Notice that the predicted and experimental spectra agree very well, once the correction for the high-energy stretches is applied.

Next, let us examine the predicted spectrum for isomer 15, which will give us insight as to how one might differentiate between the two isomers using IR spectroscopy.

The table below shows the data reported in literature for isomer 15 and compares it with the vibrational frequencies predicted by the method described above.

| Mode number | Literature vibrational frequency/cm-1 (intensity) | Stretching mode | Correction applied | Predicted vibrational frequency/cm-1 (intensity), (corrected value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3398 (s) | Yes | Yes | 3746 (s), (3670) |

| 2 | 2926 (s) | Yes | Yes | 3008 (s), (3160) |

| 3 | 1453 (m) | No | No | 1429 (m), (n/a) |

| 4 | 1381 (m) | No | No | 1382 (m), (n/a) |

| 5 | 1120 (s) | No | No | 1118 (s), (n/a) |

| 6 | 1057 (s) | No | No | 1044 (m), (n/a) |

Both molecules are very similar in structure and have exactly the same functional groups. Hence, one can imagine that differentiating the two using IR spectroscopy is no trivial task. However, we notice from the experimental data presented in those two tables that isomer 15 has a characteristic vibration at 1120 cm-1 (mode 5 shown in the picture below), which isomer 14 does not have. The predicted frequency for this vibration is of 1118 cm-1, which is very close to the experimental value. Not only that, but we observe that this vibration is reported to show up as a strong peak in the spectrum, which is also what is predicted. Finally, isomer 14 does not have a predicted peak which shows up around this frequency, and so we can infer that these predicted spectra would allow us to differentiate between the two isomers, showing once more the power of computational chemistry.

|

It should be noted that all the vibration modes of isomer 15 are not shown in pictures, since the vibrations are nearly identical for both isomers.

Finally, the log files that were returned by the SCAN suite after geometry optimisation and prediction of the vibrational frequencies of the two molecules contain information about the sum of the electronic and thermal free energies the latter. Although the values on their own do not actually reflect any physical quantity, the difference between the two values corresponds to the difference in free energy between the two molecules. Quantitatively, the log files state that for isomer 14, Sum of electronic and thermal free energies = -672.673922 hartrees = -422102 kcal/mol and that for isomer 15, Sum of electronic and thermal free energies = -672.669819 hartrees = -422100 kcal/mol The result to take away is that isomer 14 has a free energy which is 2.0 kcal/mol lower than that of isomer 15, which at least qualitatively agrees with the MM2 calculations which were carried out at the beginning of this Mini-Project. As mentioned previously, the reason for this difference in energy is the presence of a steric clash between the CH2OH and methyl groups in isomer 15 due to their both lying below the plane of the ring. This steric clash is alleviated in isomer 14, where the CH2OH group lies below the plane of the ring but the methyl groups sits above it.

Conclusion

To put it in a nutshell, we can see that even though the NMR prediction wasn't as successful as it could have been (possibly due to poor geometry optimisation for isomer 15), it still allowed us to generate two reasonable spectra which helped us assign the data reported in literature. Moreover, the predicted IR spectra are very useful in that they complement well the NMR predictions. Thus, we can say that this mini-project was a success, in the sense that it allowed us to reach sensible conclusions as to how one would go about differentiating the two isomers with standard characterisation techniques.

References

- ↑ P. Caramella, P. Quadrelli, L. Toma Chem. Rev., 1944, 34, 1

- ↑ D. Skala, J. Hanika,Pet. Coal, 2003, 45, 105

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 S. Hilf, R. H. Grubbs, A. F. M. Kilbinger J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2008, 130, 33, 11040-11048 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ref 3" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ S. Leleu, C. Papamicaël, F. Marsais, G. Dupas, V. Leavacher, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919

- ↑ L.A. Paquette, S.W. Elmore, Tet. Lett., 1991, 32, 319

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P.v.R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891

- ↑ G. Socrates, Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies, 3rd Edition, 2001, p. 65.

- ↑ J. Coates, “Interpretation of Infrared Spectra, A Practical Approach", Encyclopaedia of Analytical Chemistry, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, 2000

- ↑ X. Hu, B. Bartolomew, R. J. Nash, F. X. Wilson, G. W. J. Fleet, S. Nakagawa, A. Kato, Y. Jia, R. van Well, C. Yu, “Org. Lett.", 2010, 12, 2562-2565