Rep:Mod:lb3714TS

Transition States of Pericyclic Reactions

Aims and Introduction

The aims of this experiment were to use computational methods to locate and characterise the transition state structures of several pericyclic reactions, and to use these to predict the preferred outcome of each reaction. Sterics and secondary orbital interactions were considered in order to justify these outcomes.

Pericyclic Reactions

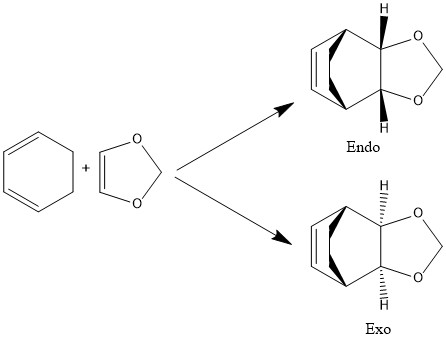

In pericyclic reactions, bond formation is concerted and there are no intermediates. The Diels-Alder reaction, an example of a pericyclic reaction, is a cycloaddition between a cis-conjugated diene and an alkene (the dienophile, which is often electron-poor) to form an unsaturated six-membered ring. This may proceed in two ways to give two different products. In the endo product, the substituents on the dienophile face towards the newly formed double bond, whereas in the exo product they face away from the double bond.[1]

The Diels-Alder reaction is governed by orbital symmetry considerations. It is classified as a [] cycloaddition, meaning that two components - a system and a system - both react suprafacially. A suprafacial component forms two bonds on the same face at both ends, whereas an antarafacial component would form two bonds at opposite faces. For a "normal demand" Diels-Alder reaction, the electron-rich diene's orbital is the HOMO, and the electron-poor dienophile's is the LUMO. In and "inverse demand" Diels-Alder reaction, the diene may contain electron withdrawing groups that lower the orbital energy, allowing it to act as the LUMO. The dienophile may contain electron donating groups that raise the energy of the orbital energy, allowing it to act as the HOMO. Under normal circumstances, the energy separation between these two orbitals is too large to allow them to significantly interact.[2]

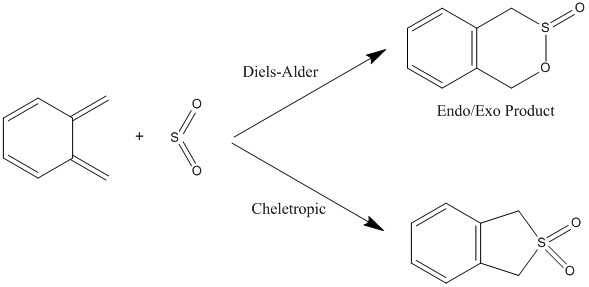

Cheletropic reactions are considered a subset of cycloaddition reactions. They differ from Diels-Alder in that the two new bonds are formed to the same atom.[3]

Nf710 (talk) 10:17, 7 April 2017 (BST) A diagram here would be good

Potential Energy Surfaces

A potential energy surface gives a visual representation of how the energy changes over the course of a reaction. Minima in the surface correspond to particular structures, such as the reactants, products or any intermediate geometries. These points have a gradient (first derivative) of zero, and positive curvature, which is calculated from the second derivative. Transition states also have a gradient of zero, but have negative curvature in one direction and positive curvature in all other directions, defining a saddle point. In order to transition between geometries, a reaction must be able to overcome the energy barrier posed by the transition state (the activation energy).

When using computational methods, a transition state can be identified by running a frequency calculation after optimisation of the structure. One imaginary (negative) frequency will be present; this indicates that in one direction the energy is at a maximum, while at orthogonal directions it is a minimum, giving positive frequencies. The normal mode corresponding to the imaginary frequency reflects a change in geometry from reactant to product, such as a change in bond length.[4] In contrast, running a frequency calculation on an optimised minimum structure would give only positive vibrational frequencies, as the energy in all directions has been minimised.

Nf710 (talk) 10:17, 7 April 2017 (BST) This is a good understanding, your could have said the potential energy surface has the dimensionality of number of degrees of freedom.

Computational Methods

This experiment made use of Gaussian. Two different computational methods were utilised to perform calculations: the semi-empirical PM6 method, and the Density Functional Theory B3LYP method. The former is a simplified version of the Hartree-Fock theory which uses experimental data to improve performance. The latter is based on an analogy of the Schrodinger equation which states that energy is a function of electron density. DFT methods give more accurate results than semi-empirical methods at the cost of requiring a higher level of computational power. The basis set of atomic orbitals used in the B3LYP method was 6-31G, which uses 6 Gaussian functions to describe inner-shell orbitals, and 3 and 1 Gaussian functions to describe the Slate-type orbitals (STO).[5]

Nf710 (talk) 10:32, 7 April 2017 (BST) B3LYP is a hybrid DFT and HF method

Exercise 1: Reaction of Butadiene with Ethylene

Associated Log Files

| Calculation | Log File |

|---|---|

| 1,3-butadiene optimisation | File:LB3714 EX1 BUTADIENE PM6.LOG |

| Ethylene optimisation | File:LB3714 EX1 ETHYLENE PM6.LOG |

| Frozen bonds optimisation | File:LB3714 EX1 FROZEN PM6.LOG |

| Transition state optimisation | File:LB3714 EX1 TS PM6.LOG |

| IRC | File:LB3714 EX1 IRC PM6.LOG |

| Product optimisation | File:LB3714 EX1 PRODUCT PM6.LOG |

Methodology

For this exercise, Method 2 was utilised. Each geometry was optimised and vibrational frequencies calculated in Gaussian, using the PM6 method. The transition state structure was carried out using the keyword opt=noeigen, and the IRC was calculated for 300 points. The changes in bond length plotted in Figure 10 were extracted from the bond distances in the IRC log file.

Molecular Orbitals

-

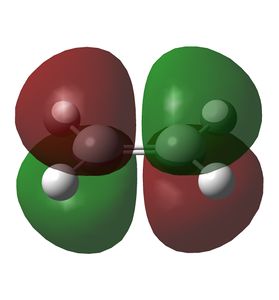

Figure 1: MO 11 of butadiene, the HOMO.

-

Figure 2: MO 12 of butadiene, the LUMO.

-

Figure 3: MO 6 of ethylene, the HOMO.

-

Figure 4: MO 7 of ethylene, the LUMO.

-

Figure 5: MO 16 of the transition state.

-

Figure 6: MO 17 of the transition state, corresponding to the HOMO.

-

Figure 7: MO 18 of the transition state, corresponding to the LUMO.

-

Figure 8: MO 19 of the transition state.

-

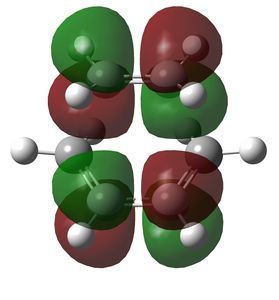

Figure 9: An MO diagram showing the frontier molecular orbitals of butadiene and ethylene.

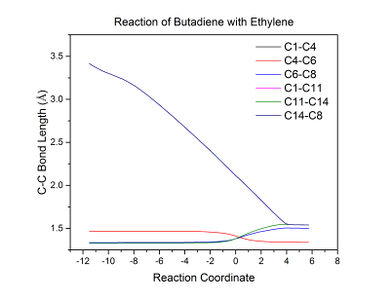

Looking at the MO diagram (Figure 9), it is clear that in order for two orbitals to interact, they must have the same symmetry. The only interactions that occur are symmetric-symmetric and antisymmetric-antisymmetric. Therefore, for the aforementioned interactions, the overlap integral SAB is nonzero, whereas it would be zero for an S-AS interaction.

This is a normal demand Diels-Alder reaction - the LUMO of the dienophile interacts with the HOMO of the diene. This is to be expected as there are no electron-withdrawing/donating groups on either substituent to affect the positioning of the energy levels. Considering this, however, the reaction is likely to be unfavourable in real life because the dienophile is not electron-poor and the LUMO would therefore not be very low in energy.

Bond Lengths

-

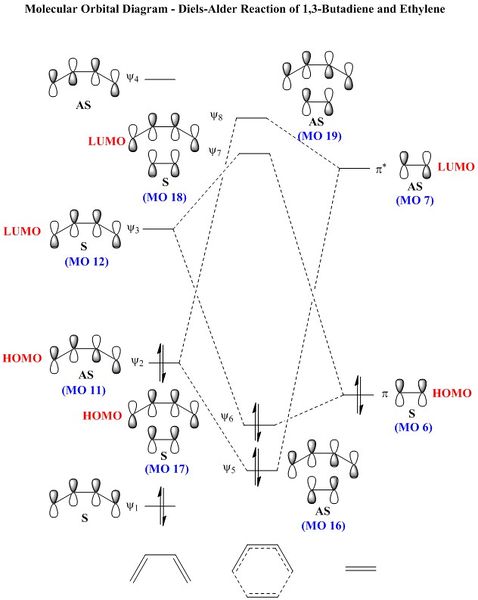

Figure 10: A graph indicating how C-C bond lengths change over the course of the reaction.

-

Figure 11: An IRC showing how the reactants approach each other.

| Figure 12: Transition State Vibration (-948.58 cm-1) | ||

|---|---|---|

Figure 10 shows that the C8-C14 (and presumably the C1-C11) bond length rapidly decreases to a constant value as the reactants approach each other and form single bonds. The C4-C6 bond decreases in length as the single bond transitions into a shorter double bond. Conversely, the C6-C8 and C11-C14 bonds increase in length as the double bonds lengthen and become single bonds. Typical sp2 and sp3 C-C bond lengths are 1.34 and 1.50-1.55 Angstroms respectively[6], which correspond well to the calculated bond lengths for the reactants and products. The bond lengths at the transition state (indicated by the gradient between plateaus corresponding to reactants and products in Figure 10) are intermediate between these values, which is to be expected.

(Fv611 (talk) 15:39, 5 April 2017 (BST) Even though you computed the bond lengths,you didn't identify which ones correspond to the reactants/TS/products. The transition state bond lengths are actually those corresponding to x = 0. You also didn't include any comparisons with the Van der Waals radii of the carbon atoms.)

Formation of the two C-C bonds (C1-C11 and C8-C14) (Figure 11) is shown to be synchronous, i.e. the two bonds are formed at the same time in a concerted manner. The above Jmol file (Figure 12) illustrates the negative vibration at -948.58 cm-1 in the transition state, which corresponds to the formation of the two bonds.

Exercise 2: Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

Associated Log Files

| Calculation | Log File |

|---|---|

| 1,3-dioxole optimisation | File:LB3714 EX2 DIOXOLE B3LYP 631G.LOG |

| Cyclohexadiene optimisation | File:LB3714 EX2 CYCLOHEXADIENE B3LYP 631G.LOG |

| Endo transition state | File:Lb3714 ex2 endo ts b3lyp 631g 2.log |

| Endo product | File:LB3714 EX2 ENDO PRODUCT B3LYP 631G.LOG |

| Exo transition state | File:LB3714 EX2 EXO TS B3LYP 631G.LOG |

| Exo product | File:LB3714 EX2 EXO PRODUCT B3LYP 631G.LOG |

Methodology

Method 3 was utilised for this exercise. Initially each geometry was optimised using the PM6 method and then further optimised using the B3LYP method with a 6-31G basis set. Each transition state structure was calculated using the keyword opt=noeigen.

Molecular Orbitals

-

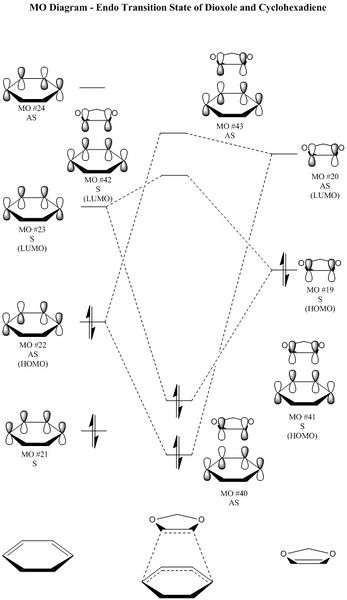

Figure 13: An MO diagram showing the frontier molecular orbitals of the endo transition state.

-

Figure 14: An MO diagram showing the frontier molecular orbitals of the exo transition state.

(Neat MO diagram and well correlated Tam10 (talk) 15:37, 3 April 2017 (BST))

| Figure 15: Endo TS HOMO | Figure 16: Exo TS HOMO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This is an inverse demand Diels-Alder reaction because dioxole, which acts as the dienophile, contains two electron donating oxygens, which donate electron density from p-orbitals into the orbitals on the adjacent carbons (a interaction). This raises the energy of MO 19, allowing it to act as the HOMO and interact with MO 23 of cyclohexadiene, which acts as the LUMO (Figures 13 and 14).

Reaction Energies

| Geometry | Free Energy (Hartrees) | Free Energy (kJ mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1,3-dioxole | -267.075 | -701204.343 |

| 1,3-cyclohexadiene | -233.337 | -612625.382 |

| Sum of reactants | -500.411 | -1313829.723 |

| Endo | ||

| Transition state | -500.351 | -1313669.739 |

| Product | -500.436 | -1313894.481 |

| Activation energy | 0.061 | 159.985 |

| Reaction energy | -0.025 | -64.758 |

| Exo | ||

| Transition state | -500.348 | -1313662.033 |

| Product | -500.435 | -1313890.989 |

| Activation energy | 0.064 | 167.691 |

| Reaction energy | -0.023 | -61.266 |

-

Figure 17: Diagrams showing the presence/absence of secondary orbital interactions in the endo and exo transition states.

(You're using the wrong MO for dioxole. This would be unfavourable - compare to the TS MOs you've shown above Tam10 (talk) 15:37, 3 April 2017 (BST))

-

Figure 18: Diagrams showing the presence of the destabilising steric clash in the exo transition state.

As seen in Table 1, the endo reaction gives the favoured kinetic product because its reaction barrier/activation energy is slightly lower than that of the exo reaction. It also gives the preferred thermodynamic product because the energy of the product is lower than that of the exo product. In the endo transition state, a stabilising secondary orbital interaction is possible (Figure 15); the p-orbitals on the dioxole oxygens donate electron density into the newly formed double bond (Figure 17). Additionally, there is a destabilising steric clash between the sp3 hydrogens in the exo transition state (Figure 18), leading to a less stable product.

Nf710 (talk) 10:30, 7 April 2017 (BST) Good section, your values are correct and your have come to the correct conclusions. Good section

Exercise 3: Diels-Alder vs Chelotropic

Associated Log Files

Methodology

Method 3 was again utilised for this exercise. All geometries were optimised, and IRCs and frequencies calculated, using the PM6 method. When calculating transition states, the keyword opt=noeigen was used. IRCs were calculated for 300 points.

Reaction Coordinates

-

Figure 19: The IRC of the endo reaction Media:Lb3714_ex3_endo_irc_small.gif.

-

Figure 20: The IRC of the exo reaction

-

Figure 21: The IRC of the cheletropic reaction.

Figures 19 and 20 indicate that the formation of the two new bonds is asynchronous - the C-O bond is formed before the C-S bond. However, the bond formation in the cheletropic reaction is synchronous (Figure 21), presumably because the sulfur atom donates its two lone pairs to the xylylene at the same time. During the course of each reaction, the xylylene ring becomes a planar, aromatic ring, conferring thermodynamic stability.

Reaction Energies

| Geometry | Free Energy (Hartrees) | Free Energy (kJ mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| o-Xylylene | 0.178 | 467.75 |

| SO2 | -0.119 | -313.14 |

| Reactants | 0.059 | 154.61 |

| Endo | ||

| Endo TS | 0.091 | 237.76 |

| Endo product | 0.022 | 56.98 |

| Endo reaction barrier | 0.032 | 83.15 |

| Endo reaction energy | -0.037 | -97.62 |

| Exo | ||

| Exo TS | 0.092 | 241.75 |

| Exo product | 0.021 | 56.33 |

| Exo reaction barrier | 0.033 | 87.14 |

| Exo reaction energy | -0.037 | -98.28 |

| Cheletropic | ||

| Cheletropic TS | 0.099 | 260.09 |

| Cheletropic product | 0.000 | 0.01 |

| Cheletropic reaction barrier | 0.040 | 105.48 |

| Cheletropic reaction energy | -0.059 | -154.60 |

-

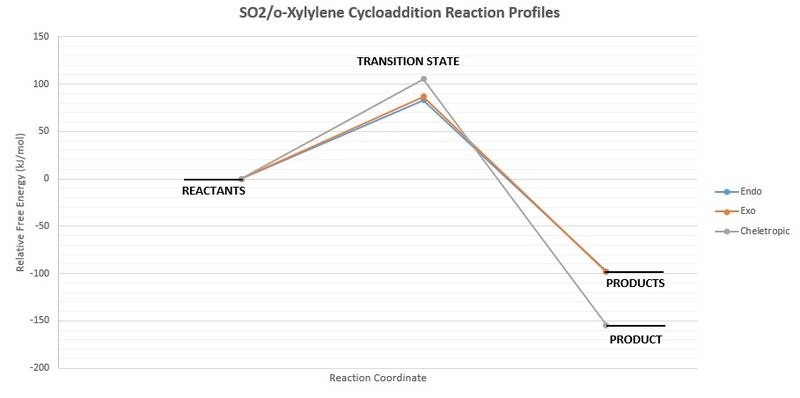

Figure 22: Reaction profiles showing the relative energies associated with each reaction.

From Figure 22, it is clear that despite having the highest reaction barrier and therefore being kinetically unfavourable, the chelotropic reaction is thermodynamically preferred as it gives by far the most energetically stable product. This is because a five-membered ring is formed, which is energetically preferred over the six-membered ring formed in the Diels-Alder reactions. Table 2 indicates that the endo reaction is kinetically favoured over the exo reaction as it has a slightly lower reaction barrier, whereas the exo reaction is thermodynamically favoured as it gives a lower-energy product.

Comparing the Two Potential Reaction Sites on o-Xylyene

| Geometry | Free Energy (Hartrees) | Free Energy (kJ mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Endo (site 2) | ||

| Product | 0.066 | 172.26 |

| Activation Energy | 0.043 | 113.37 |

| Reaction Energy | 0.007 | 17.65 |

| Exo (site 2) | ||

| Product | 0.067 | 175.71 |

| Activation Energy | 0.046 | 121.21 |

| Reaction Energy | 0.008 | 22.11 |

-

Figure 23: Reaction profiles showing the relative energies associated with reactions at each diene site on o-xylyene.

As shown in Figure 23, both the endo and exo reactions at the second cis-butadiene fragement on o-xylene are very kinetically unfavourable compared to the reaction at the first fragment because the energy barrier to the transition state is noticeably higher. They are also thermodynamically unfavourable because the relative energies of the products are higher than that of the reactants, whereas the products from the reaction at the first site are much lower in energy. This may be because the second butadiene fragment contained in the ring is more difficult to access by SO2, and does not confer extra stability by introducing aromaticity into the product.

Conclusions

The aims of this experiment were to calculate the transition state structures and energies of several pericyclic reactions, and to relate them to the effects of sterics and secondary orbital interactions. Exercise 1 illustrated the importance of symmetry for pericyclic reactions, namely that only orbitals of the same symmetry may interact. For Exercise 2, it was found that the endo reaction was both kinetically and thermodynamically favoured over the exo reaction due to the possibility of stabilising secondary orbital interactions in the transition state, and also because the exo structure contained destabilising steric interactions between sp3 hydrogens. For Exercise 3, the chelotropic reaction was found to be the favoured thermodynamic product because it formed a more energetically favourable five-membered ring, whereas the Diels-Alder products were kinetically favoured. There were two possible diene reaction sites on o-xylylene, and the energetics of reactions at each site were calculated and compared. It was found that the site outside of the ring was highly favoured both kinetically and thermodynamically; this is because the site inside of the ring was more difficult to access by SO2, and additionally did not lead to the stabilising formation of an aromatic ring.

References

- ↑ J. Clayden, N. Greeves, S. Warren and P. Wothers, in Organic Chemistry, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1st edn., 2001, ch. 35, pp. 905-942.

- ↑ F.A. Carey and R.J. Sundberg, in Advanced Organic Chemistry: Part A: Structure and Mechanisms, Springer Science & Business Media, 2007, ch. 10, pp. 836-850.

- ↑ I. Fleming, Frontier Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions, Wiley, 1977.

- ↑ Transition States in Chemical Reactions, http://people.chem.ucsb.edu/kahn/kalju/chem111/public/qm_ts_hcn_hnc.html, (accessed March 2017).

- ↑ Computational Methods Summary, http://glab.cchem.berkeley.edu/glab/tutorials_supporting-docs/CalculationMethods-Overview-052313.pdf (accessed March 2017).

- ↑ A. A. Zavitsas, J. Phys. Chem A., 2003, 107, 897-898.