Rep:Mod:kwlittle1

Hydrogenation of the Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Introduction

Molecular mechanics calculations were used to determine the relative stability of cyclopentadiene dimer stereoisomers (1 and 2), and of two hydrogenation products (3 and 4) of the endo isomer. From these relative energies, the thermodynamic products of both the dimerisation and hydrogenation reactions were found, to determine whether the reactions are kinetically or thermodynamically controlled.

Method

As Avogadro is extremely buggy software in Windows 8, crashing upon the use of common keyboard shortcuts such as ctrl-V and ctrl-Z, ChemBio 3D was used to draw all molecules, which were first optimised by MM2, then imported into Avogadro for optimisation with MMFF94s, using the conjugate gradients algorithm until convergence.

Results

| Molecule | Bond Stretching | Angle Bending | Stretch Bending | Torsional | Out-of-Plane Bending | van der Waals | Electrostatic | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo (1) | 3.54296 | 30.77300 | -2.04138 | -2.27377 | 0.01469 | 12.80827 | 13.01393 | 55.37370 |

| Endo (2) | 3.46672 | 33.20112 | -2.08182 | -2.95080 | 0.02141 | 12.34994 | 14.18390 | 58.19056 |

| 3 | 3.31179 | 31.96902 | -2.10439 | -1.50341 | 0.01311 | 13.64014 | 5.11951 | 50.44578 |

| 4 | 2.82318 | 24.68541 | -1.65722 | -0.37893 | 0.00028 | 10.63777 | 5.14701 | 41.25749 |

Discussion

The energies given by MM calculations are not relatable to absolute thermodynamic properties such as G; however, they are comparable between similar molecules as a measure of thermodynamic stability. Thus the data above show that the exo product of dimerisation is more thermodynamically stable, mostly due to less angle bending energy as the carbon atoms on the dienophile part are closer to tetrahedral, and a lower electrostatic repulsion due to greater distance between the two alkene groups. As the endo product is formed, it is clear that the dimerisation must occur under kinetic control, further evidenced by the fact that the dimer is preferred at lower temperatures and dissociates into monomers upon heating.

Of the hydrogenation products, 4 is more stable, suggesting that the alkene in the diene part is more facile to hydrogenation.

Introduction

Atropisomerism occurs when rotation about a single bond has a high energy barrier. It is often found in macrocyclic structures, such as this intermediate in the synthesis of an anti-cancer drug, Taxol:

Molecular mechanics calculations were used to determine which of these atropisomers is most stable. Molecules with a double bond adjacent to a bicyclic junction, so-called 'bridgehead' alkenes, have been shown[1] to have an unusually high stability and be less hindered than the parent alkane. This has also been investigated.

Method

The molecules (labelled 9 and 10) and the alkane of 10 were drawn in ChemBio 3D and optimised with MM2, then imported into Avogadro and further optimised with MMFF94s, using the Conjugate Gradients algorithm until convergence. Upon inspection, the cyclohexane group of both molecules was in a twist-boat-like conformation. An atom was manually moved to the position of a chair conformer and the MMFF94s optimisation ran again, further decreasing the energies of each molecule by around 6 kcal/mol.

Results

| Molecule | Bond Stretching | Angle Bending | Stretch Bending | Torsional | Out-of-Plane Bending | van der Waals | Electrostatic | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 8.84817 | 33.37610 | 0.06559 | 3.26950 | 1.39986 | 36.24943 | 0.25690 | 83.46556 |

| 10 | 7.57940 | 18.89899 | -0.13751 | 0.32618 | 0.84797 | 33.11434 | -0.04456 | 60.58482 |

| Alkane of 10 | 6.39633 | 22.34160 | 0.29429 | 9.27903 | 0.03494 | 31.20290 | 0.00000 | 69.54910 |

Discussion

Product 10 is clearly favoured. By inspection, its macrocyclic ring is less hindered, being able to adopt geometries close to tetrahedral at each atom; this is reflected in the much lower angle bending energy than 9. The electrostatic energy in 10 is negative, indicating an attractive force: this is most likely between the ketone carbon and the alkene's pi bond. The alkene is more stable than the equivalent alkane, but the electrostatic attraction is a negligible factor in this: it is a special property of bridgehead alkenes called hyperstability. The alkane has far greater stretch bending and torsional energies, showing that the bridgehead alkene allows a bicyclic system to adopt bond angles and lengths closer to ideality. Olefin strain energy is defined as the difference between total strain energies of the most stable alkane conformer and the most stable alkene conformer. A molecular orbital explanation of olefin strain suggests that the twisting of the double bond lowers the HOMO-LUMO gap; however, this does not explain hyperstability.

Introduction

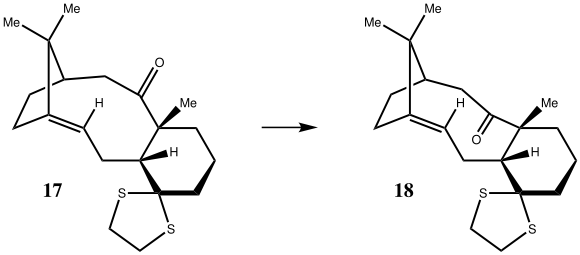

Quantum mechanical computations are more advanced than molecular mechanics, and can be used to predict NMR and IR spectra. A further intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol (18) was optimised and its NMR spectrum predicted and compared to literature.

Method

The molecule was drawn in ChemBio 3D and optimised with MM2, then imported into Avogadro and further optimised with MMFF94s, using the Conjugate Gradients algorithm until convergence. Manual adjustment of the cyclohexane ring to a chair conformer was at first unsuccessful. Adjusting the 5-membered ring to an envelope conformation was found to be unfavourable, but adjusting to the opposite twist conformer allowed access to the chair conformation in the 6-membered ring, which was optimised again with MMFF94s and found to be the most stable.

Optimised Intermediate 18 |

The optimised molecule was submitted to the HPC cluster for quantum mechanical calculations in Gaussian. The B3LYP theory and 6-31G(b,p) basis set were used with carbon and hydrogen polarisation. A solvation model for chloroform and empirical dispersion parameter of GD3 were also used.

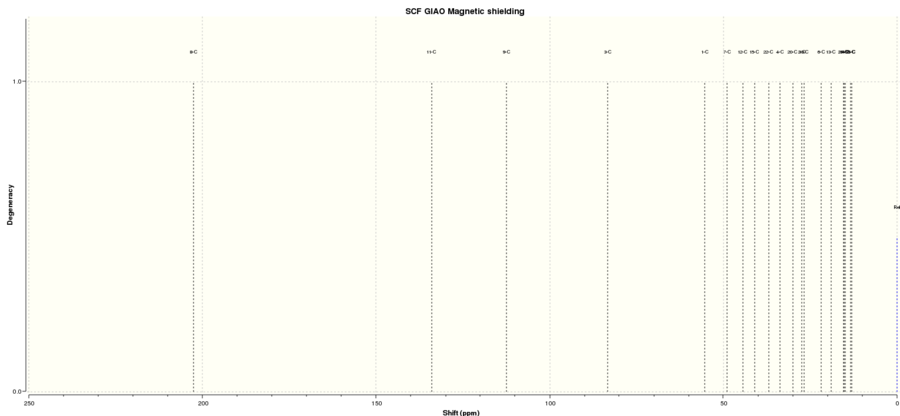

Results

Full calculation data can be found at DOI:10042/25976 . The JMol visualisation above has atom labels for precise assignment with the spectra below.

Discussion

As this calculation method does not take into account coupling, and due to the large number of hydrogen atoms, the 1H comparisons that can be made with real spectra are limited. Thus, I will compare the 13C peaks to literature values[2]:

| Calculated | Literature | Difference |

|---|---|---|

| 202.37 | 211.49 | -9.12 |

| 133.52 | 148.72 | -15.20 |

| 112.91 | 120.90 | -7.99 |

| 80.44 | 74.61 | 5.83 |

| 51.79 | 60.53 | -8.74 |

| 48.28 | 51.30 | -3.02 |

| 44.48 | 50.94 | -6.46 |

| 41.22 | 45.53 | -4.31 |

| 36.97 | 43.28 | -6.31 |

| 35.18 | 40.82 | -5.64 |

| 32.29 | 38.73 | -6.44 |

| 32.02 | 36.78 | -4.76 |

| 26.22 | 30.00 | -3.78 |

| 20.95 | 25.56 | -4.61 |

| 20.23 | 25.35 | -5.12 |

| 18.27 | 22.21 | -3.94 |

| 15.32 | 21.39 | -6.07 |

| 14.16 | 19.83 | -5.67 |

| 13.41 | ||

| 11.83 |

Note that the peaks at 80.44, 35.18 and 32.02 ppm are less accurate, as these are for the carbons bonded to sulphur atoms. Heavy atoms like halogens and sulphur cause spin-orbit coupling errors. A correction value has not been calculated for sulphur, but applying an assumed correction of -3 ppm, the value for similar-weighted chlorine, would not improve agreement with the literature values. There is a mean difference of roughly 6 ppm between the calculated and measured spectra. Over the large ppm range of a 13C spectrum, this is accurate enough to determine many functional groups. As the literature provided does not include assignments, assessing the accuracy of calculations for individual atoms is not possible. Though care was taken to find the most stable conformer of 18, there is a chance that another conformer is available which would give more-accurate calculated values.

Crystal structures of epoxidation catalysts

Introduction

The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre was searched for crystal structures of both the Shi and Jacobsen epoxidation catalysts. These structures were analysed using the Mercury software to find any interesting conformational patterns the catalysts adopt in the solid state.

Shi

The 3D stick diagram below shows non-bonded atom distances of less than the sum of their van der Waals radii as dotted lines. These short distances can be seen to only occur between oxygen and hydrogen atoms, indicating an attractive dipole-dipole interaction, which is strongest for the ketone oxygen. The C-O bond lengths about the anomeric centres are shown on the left. These are distorted slightly from the equal lengths one might expect to see. Interestingly, this distortion is probably not due to dipole interactions, as for one anomeric centre it is the oxygen atom with the longer bond which is close to an adjacent molecule's hydrogen atom; at the other centre, it is the oxygen with the shorter bond.

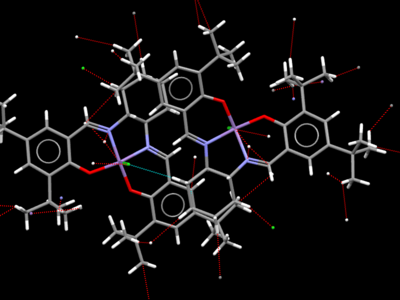

Jacobsen

As with the Shi catalyst, the Jacobsen catalyst's crystal structure shows evidence of dipole interactions, this time not with oxygen atoms but between Cl, N and Mn with nearby hydrogens. Unlike in the Shi catalyst, there are many interactions between hydrogen atoms with each other or with carbon. These are most notable where the bulky tert-butyl groups are packed together, eclipsing the aromatic rings of adjacent molecules. This can be seen in the second image.

NMR spectra of styrene oxide and trans-stilbene oxide

Introduction

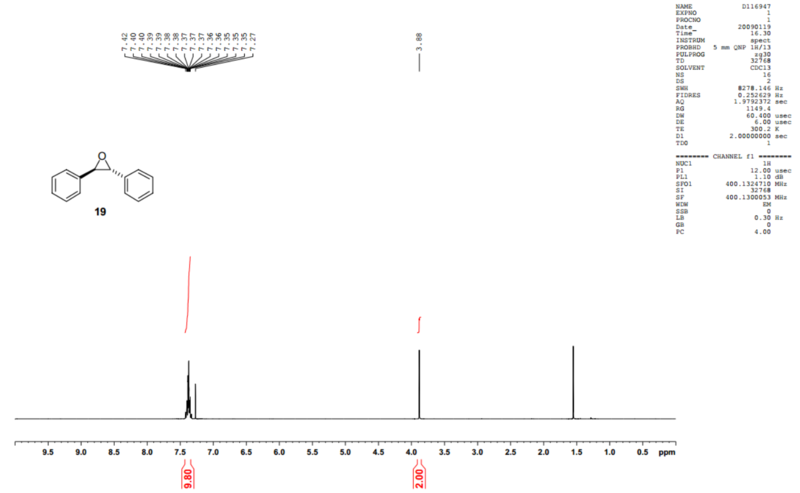

As above with the Taxol intermediate, NMR spectra were predicted for the two epoxides of the alkenes used in the lab: styrene oxide and trans-stilbene oxide. Due to time constraints, the latter was not synthesised in the lab, and optical characterisation of the former was not possible. As chirality has no effect on NMR spectra in such systems, only the R and R,R enantiomers, respectively, of each molecule were studied.

Method

The molecules were drawn in ChemBio 3D, optimised with MM2, then in Avogadro were optimised with MMFF94s using the Conjugate Gradients algorithm. They were submitted to Gaussian for quantum mechanical optimisation and NMR spectrum prediction using the following keywords:

# b3lyp/6-31g(d,p) opt scrf(cpcm,solvent=chloroform) NMR EmpiricalDispersion=GD3

As the above calculations do not include couplings, the fully-optimised outputs were then resubmitted for coupling calculations with the following keywords:

# b3lyp/6-311+G(d,p) scrf(cpcm,solvent=chloroform) NMR(spinspin,mixed)

The shifts and coupling constants were typed into gNMR for calculation to produce the spectra shown below.

Results

Calculation data for styrene oxide[3][4] and trans-stilbene oxide[5][6] are available.

Discussion

Literature spectra for styrene oxide[7] and trans-stilbene oxide[8] were found:

While the aromatic peaks are accurate, the others are upshifted by about 0.25ppm.

Absolute configurations of epoxide products

Introduction

There are many methods for determining the configuration of a reaction product. Properties such as optical rotation, electronic and vibrational circular dichromism spectra can be calculated for a given enantiomer and compared with experimental results from the lab or literature. Alternatively, the relative energies of different transition states can be analysed to determine which is the more stable, and thus more likely pathway. As optimisation of transition states takes an inhibitive amount of time, this has been done with given data for β-methyl-styrene epoxide rather than the epoxides examined in the lab.

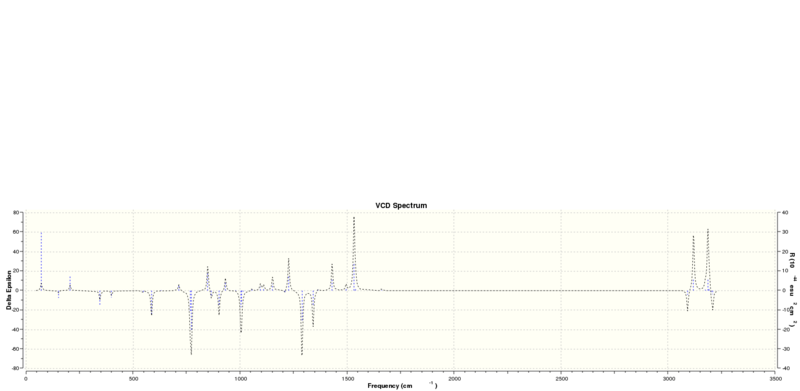

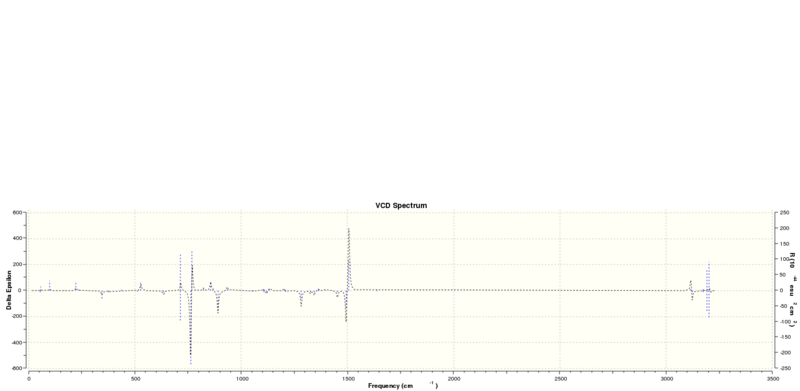

Calculated chiroptical properties of styrene epoxide and trans-stilbene epoxide

Using the NMR calculations above included the freq(vcd) keyword for computing the vibrational circular dichromism spectrum. The optimised output molecules from those calculations were submitted for optical rotation calculation using the Cambridge version of the B3LYP method. However, at the time of writing on Friday afternoon, I realised that I had not specified the wavelength in the input file, thus the jobs had been computing endlessly since Wednesday. Calculations for the ECD spectrum[9][10] failed for an unknown reason. The VCD spectra are shown below:

Calculated energies of transition states of β-methyl-styrene epoxide

The most-likely product of a reaction can be determined from the free energies of the transition states, with the most-stable transition state giving the major product. Furthermore, the ratio of the products, K, can be fround from the free energy difference:

Using the final given transition states for trans-β-methyl-styrene with the Shi catalyst[11][12]:

| Enantiomer | Energy / Hartree | Energy / Jmol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| R,R | -1343.032443 | -3.525460163×109 |

| S,S | -1343.024742 | -3.525439948×109 |

For this pair, K=7375 in favour of the R,R enantiomer, which gives an enantiomeric excess of 99.99%.

Non-covalent interactions and electronic topology of transition states of b-methyl-styrene oxide

The non-covalent interactions of the transition state of the formation of (R,R)-β-methyl-styrene oxide with the Shi catalyst are shown below:

Pentahelicene |

And for the S,S enantiomer:

Pentahelicene |

Green areas show an attractive force, and there appears to be a greater amount of attraction near the site of epoxidation with the R,R enantiomer than for the S,S enantiomer, further evidencing the fact that the R,R form is favoured.

References

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ Spectroscopic data: L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ Styrene oxide NMR calculations: DOI:10042/26007

- ↑ Styrene oxide coupling calculations: DOI:10042/26008

- ↑ trans-Stilbene oxide NMR calculations:DOI:10042/26009

- ↑ trans-Stilbene oxide coupling calculations: DOI:10042/26010

- ↑ K. Huang H. Wang et al., J. Org. Chem., 2011, 76 (6), 1883-1886DOI:10.1021/jo102294j

- ↑ N. J. Findlay S. R. Park. et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc.,2010, 132 (44), 15462–15464 DOI:0.1021/ja107703n

- ↑ Styrene oxide ECD calculations: DOI:10042/26013

- ↑ trans-Stilbene oxide ECD calculationsL DOI:10042/26014

- ↑ Shi 4th R,R transition state: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.738037

- ↑ Shi 4th S,S transition state: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.739117