Rep:Mod:knt11y3s1c

Y3S1C: Third year Synthesis Laboratory Module 1C

Name: Kai Ni Teh

CID: 00697229

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the use of computational methods and modelling has become more prevalent in determining the outcome of reactions and the stability and properties of compounds. With this understanding in mind, this computational exercise consists of two parts, the first with the aim to introduce basic computational techniques and the second with the aim to assign stereochemistry of compounds synthesised in a related organic synthesis laboratory session. Instead of UFF, which is a method that can be used across the periodic table of elements but is a simpler model which fixes the hybridisation of each atom, MMFF94s is used.

Conformational analysis using Molecular Mechanics

This part of the exercise compares the energies of related compounds, isomers or atropisomers in some cases, to determine and explain the relative stability of one of the compounds.

Cyclopentadiene dimerisation

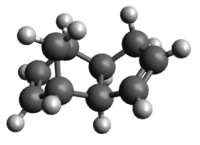

Cyclopentadiene dimerises readily and the two dimers are the exo and endo dimers, as shown in Figure 1.

The MMFF94s method is run to determine the energies of the exo and endo dimers and the results are shown in Table 1.

A reaction under thermodynamic control means that the product that is more thermodynamically stable with a lower total energy is preferentially formed, whereas a reaction under kinetic control means that the product with a lower activation energy barrier to achieve its transition state will be preferentially formed.

Cyclopentadiene dimerisation is an example of Diels Alder cycloaddition reaction with π2s + π4s or π4s + π2s components.

Comparing the total energies of the exo and endo dimers, it is clear that the exo dimer is the thermodynamically more stable product given its lower energy, predominantly because it has a smaller degree of ring strain. However, it is a well-known fact that Diels Alder cycloaddition reactions usually produce the endo product preferentially. This can be explained by secondary orbital interactions derived from the endo transition state, which is absent in the exo transition state.[1] Hence, the endo dimer is the product under kinetic control with a smaller activation energy barrier to achieve the endo transition state and it is formed at a faster rate. This is confirmed by a study performed by Caramella et al.[2] revealing the fact that the endo transition state (21.0 kcalmol-1) is 2.9 kcalmol-1 lower in energy than the exo transition state (23.9 kcalmol-1). The preferential formation of the endo dimer also illustrates the overriding effect of this favourable secondary orbital interactions over the higher angle strain observed in the endo dimer.

Cyclopentadiene hydrogenation

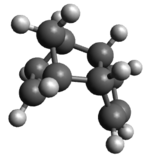

Partial hydrogenation of the endo dimer initially produces one of the dihydro derivatives 3 or 4, as shown in Figure 2, instead of the tetrahydro derivative which is only formed after prolonged hydrogenation.

The MMFF94s method is run to determine the energies of the dihydro derivatives and the results are shown in Table 2.

With a double bond in the norbornene ring, Compound 3 has a much larger ring strain and this leads to a higher angle bending energy, resulting in a much higher total energy. From the results in Table 2, it is clear that Compound 4 is the thermodynamic product with a much lower energy. Compound 4 also has a lower van der Waals energy, indicating a smaller van der Waals repulsion energy and a larger intermolecular interaction, leading to a more stable product with lower total energy.

In fact, the observation of the preference for partial hydrogenation on the norbornene ring is also supported by Skála et al and they found that using Pd/C catalyst, the rate of hydrogenation of the alkene in the norbornene ring is much higher than that of the other alkene of the endo dimer even though both hydrogenation processes are exothermic.[3]

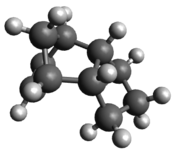

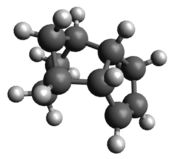

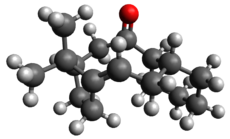

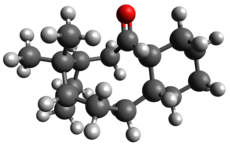

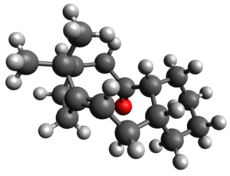

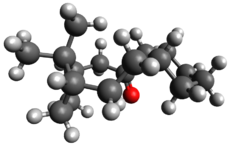

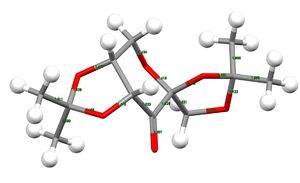

Compounds 9 and 10 are intermediates in the synthesis of taxol, their and their parent hydrocarbons' structures are shown in Figure 3.

The MMFF94s method is run to determine the energies of these intermediates and the results are shown in Table 3.

This taxol intermediate is an example of atropisomerism, where there is sufficiently large rotation barrier about the C-C bonds allowing the isolation of both isomers (Compounds 9 and 10 in this case). For example, with the presence of a large OTBS substituent on the cyclohexane ring, only Compound 10, with the carbonyl pointing downwards, was produced.[4]

From Table 3, it is clear that Compound 10 is thermodynamically more stable than Compound 9 and this is predominantly due to a much smaller angle strain. This could be due to the proximity of the carbonyl and the bridging alkyl groups in Compound 9, resulting in a larger repulsion. This is in contrast with a further distance between the carbonyl and -CH2CH2- group in Compound 10, and hence a smaller repulsion.

While trying to optimise the structures of Compounds 9 and 10 (including manual editing), it was found that there are two alternative cyclohexyl twist boat conformations that give rise to much higher total energy. This is because chair conformations are known to be more stable than the twist boat analogues due to the absence of torsional strain in the chair conformation since all hydrogen atoms are staggered with respect to each other. During manual editing, as long as a chair conformation is obtained from the twist boat analogue, the total energy decreases massively; hence, both Compounds 9 and 10 are presented in the chair form in the table above.

During subsequent alkene functionalisation, it was observed that the alkene in Compounds 9 and 10 were very unreactive or reacted very slowly. Firstly, in these compounds, the alkene is positioned at a bridgehead position and they can only be isolated due to a large ring size according to Bredt's rule[5]. However, the alkenes are not just typical bridgehead alkenes, they are classified as hyperstable olefins, being more stable than their parent hydrocarbons with a smaller olefin strain ("the difference between the strain energy of an olefin and that of its parent hydrocarbon"[6]). This phenomenon is verified by computational calculations whereby Compounds 9 and 10 both have lower total energy as compared to their parent hydrocarbons and the results are summarised in Table 3. In each case, there is a much larger angle strain in the parent hydrocarbons and this is because the alkenes are encapsulated in a cage structure and they experience less strain than their parent hydrocarbons,[6] resulting in an unusual stability and hence unreactivity. In fact, the extent of unreactivity can be so severe that some hyperstable olefins, such as bicyclo[4.4.4]tetradec-1-ene, will not even undergo simple hydrogenation reactions under normal conditions. [6]

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

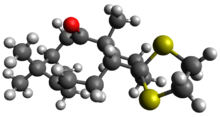

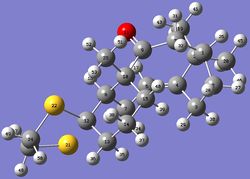

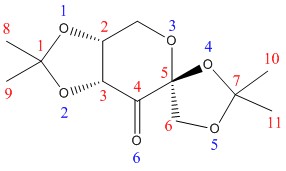

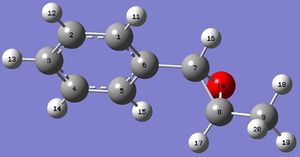

This part of the exercise exemplifies, by using Compound 17, the use of computational methods to derive the NMR spectra of compounds. Compound 17 is a derivative of Compound 9 and it is also an intermediate in the synthesis of taxol. Its structure is shown below in Figure 4.

Energy optimisation of Compound 17

The structure and energy of Compound 17 are first optimised in ChemBio 3D Ultra 13.0 then the method MMFF94s is run to determine its energy and the results are summarised in Table 4.

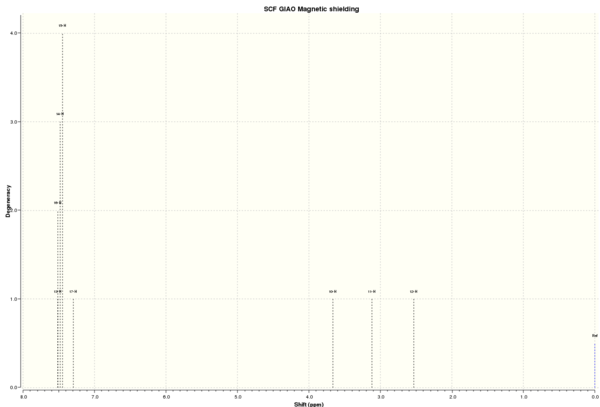

NMR spectra of Compound 17

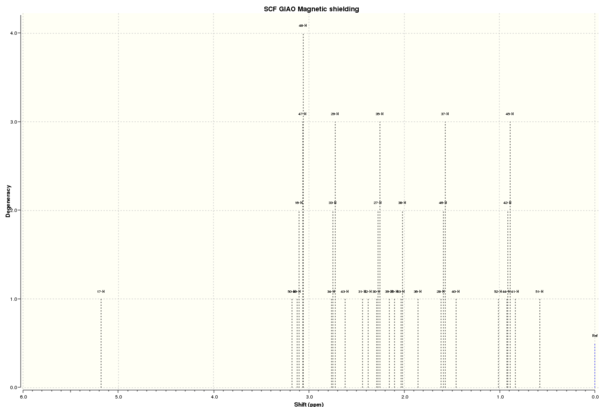

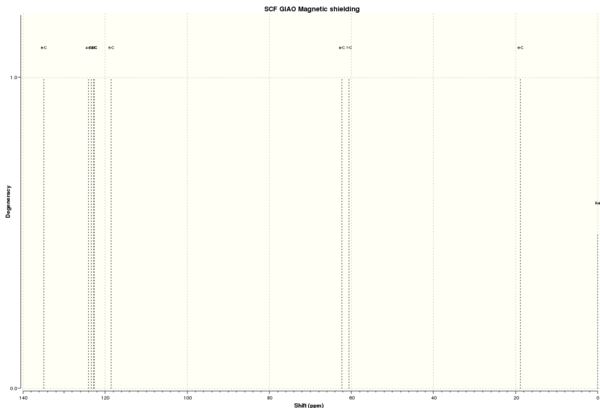

After energy optimisation, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of Compound 17 are computed using Avogadro. The spectra and spectral data are presented below in Tables 5 and 6. In each spectrum, the solvent used was chloroform.

1H NMR spectrum

| 1H NMR chemical shift /ppm | |||||

| |||||

| DOI:10042/26524 To enlarge the spectrum, click on the spectrum. | |||||

| Atoms | Calculated value | Literature value[7] | Absolute difference | Calculated integration | Literature integration[7] |

| 17 | 5.18 | 4.84 | 0.34 | 1 | 1 |

| 50 | 3.18 | 2.99 | 0.19 | 1 | 1 |

| 16, 47, 48, 49 | 3.09 | 3.40-3.10 | < 0.31 | 4 | 4 |

| 29, 33, 34 | 2.74 | 3 | |||

| 43 | 2.62 | 1 | |||

| 31 | 2.44 | 1 | |||

| 32 | 2.38 | 1 | |||

| 27, 30, 35 | 2.27 | 3 | |||

| 39 | 2.16 | 1 | |||

| 26 | 2.10 | 1 | |||

| 38, 53 | 2.03 | 2 | |||

| 36 | 1.85 | 1 | |||

| 28, 37, 46 | 1.59 | 1.25 | 0.34 | 3 | 3 |

| 40 | 1.46 | 1 | |||

| 52 | 1.01 | 1 | |||

| 42, 44, 45 | 0.91 | 1.10 | 0.2 | 3 | 3 |

| 41 | 0.84 | 1 | |||

| 51 | 0.58 | 1.00-0.80 | <0.42 | 1 | 1 |

The computation correctly assigns the most deshielded chemical shift to H17 which is an alkenyl hydrogen due to ring currents of the alkene. The next most deshielded hydrogen atoms are those attached to the carbon atoms adjacent to sulphur with chemical shifts above 3 ppm. The group of hydrogen atoms positioned spatially relatively close to the alkene group are also more deshielded than usual alkyl hydrogens and show up as peaks above 2 ppm due to ring currents of alkene but the effect of ring currents is certainly much smaller than H17 which is directly attached to the alkenyl carbon. The other hydrogen atoms are alkyl hydrogen atoms and they produce peaks at about 0.5 - 1.5 ppm depending on their exact chemical environment.

Comparison with the 1H NMR data of Compound 17 by Paquette et al[7] leads to some chemical shifts being unassigned and these are the 14 hydrogen atoms showing up as multiplets in the region of 2.80-1.35 ppm and 3 hydrogen atoms showing up as a singlet at 1.38 ppm. For the rest of the hydrogen atoms that could be corresponded to those in the literature, they are generally in good agreement with the literature with the biggest deviation of 0.42 ppm. This could be because the computation calculates the chemical shift for individual hydrogen atoms based on their exact positions in a 'frozen' instant without accounting for the fact that there could be C-C bond rotation given sufficient energy at room temperature, rendering the protons chemically and magnetically equivalent. This is despite the fact that some hydrogen atoms remain chemically and magnetically inequivalent given their different chemical environments. For instance, H44, H45 and H46 should produce just one peak at approximately 1 ppm due to C-C bond rotation; however, from the computation (Table 5), they are split into 2 peaks with a large 0.68 ppm difference. The same applies to H51, H52 and H53, which are split into three peaks with a very large deviation of 1.45 ppm. After the calculated chemical shifts are averaged for equivalent protons, the deviation in chemical shifts is in fact small and acceptable, 1.14 ppm compared to 1.10 ppm for H44, H45 and H46; 1.20 ppm compared to 0.80-1.00 ppm for H51, H52 and H53. Therefore, it can be concluded that the computations are generally successful and the results agree well with literature values.

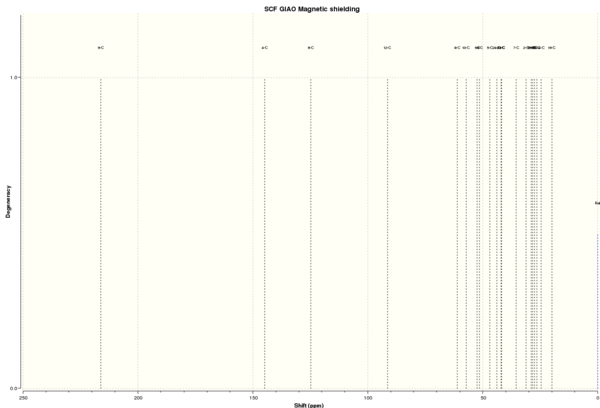

13C NMR spectrum

| 13C NMR chemical shift /ppm | ||||

| ||||

| DOI:10042/26524 To enlarge the spectrum, click on the spectrum. | ||||

| Atom number | Calculated value | Literature value[7] | Absolute difference | |

| 9 | 216.27 | 218.79 | 2.52 | |

| 4 | 144.86 | 144.63 | 0.23 | |

| 6 | 124.71 | 125.33 | 0.62 | |

| 12 | 91.35 | 72.88 | 18.47 | |

| 8 | 60.96 | 56.19 | 4.77 | |

| 10 | 57.08 | 52.52 | 4.56 | |

| 1 | 52.46 | 48.50 | 3.96 | |

| 18 | 51.48 | 46.80 | 4.68 | |

| 5 | 46.92 | 45.76 | 1.16 | |

| 24 | 43.87 | 39.80 | 4.07 | |

| 23 | 41.95 | 38.81 | 3.14 | |

| 13 | 41.87 | 35.85 | 6.02 | |

| 7 | 35.440 | 32.66 | 2.78 | |

| 2 | 31.20 | 28.79 | 2.41 | |

| 15 | 28.94 | 28.29 | 0.65 | |

| 25 | 28.36 | 26.88 | 1.48 | |

| 3 | 27.37 | 25.66 | 1.71 | |

| 20 | 26.33 | 23.86 | 2.47 | |

| 14 | 24.55 | 20.96 | 3.59 | |

| 19 | 19.78 | 18.71 | 1.07 | |

Note: calculated and literature values of integration are 1 carbon atom per signal.

C9 is the most deshielded carbon atom in Compound 17 because it is directly and doubly bonded to the electronegative oxygen atom. C4 and C6 correspond to the alkenyl carbons; hence, they are also very deshielded due to ring currents. C12 is more deshielded than typical alkyl carbons because it is attached to 2 sulphur atoms.

C2, C15, C25, C3, C20, C14 and C19 are carbon atoms in the carbon framework; hence, they have chemical shifts of typical alkyl carbons of 15-30 ppm. C8, C10, C18, C4, C24, C23, C13 and C7 are carbon atoms in close proximity to alkenyl carbons, sulfur atoms or carbonyl groups. Therefore, they are more deshielded, to different extent depending on the group they are close to, than typical alkyl carbons. C1 is unexpectedly more deshieleded than a typical alkyl carbon and this might be because it is in rather close proximity with both the alkene and carbonyl groups.

As explained above, the deviation between calculated and literature values are within an acceptable range with the second largest deviation of 6.02 ppm. However, it is very important to note a very large deviation of 18.47 ppm for C12 and this is because there needs to be a correction factor for spin-orbit coupling for carbon atoms attached to heavy atoms like sulfur. Since the correction factor was not included in the computation, the large deviation is expected.

Analysis of the properties of the alkene epoxides

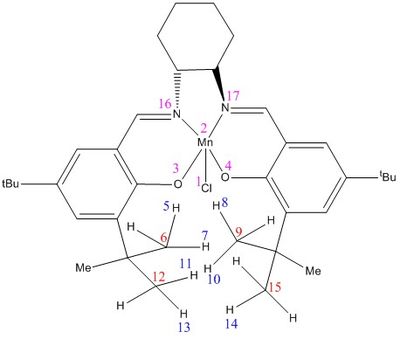

In the two week synthesis experiment 1S, the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts were synthesised and they have the structures shown in Figure 5.

These catalysts were used as catalysts in alkene epoxidation reactions and various properties of the epoxides are analysed in this section of the exercise. The two alkenes used were styrene and methylstyrene and the respective epoxides were obtained with the addition of appropriate reagents and the use of catalysts, as shown in Figure 6.

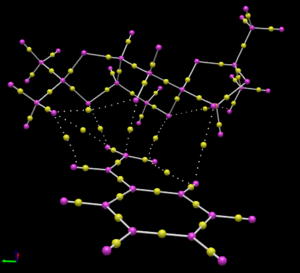

Crystal structure of the catalysts

The crystal structures of compounds 21 and 23 are obtained by searching the Cambridge crystal database (CCDC) using the Conquest program.

Shi catalyst (Compound 21)

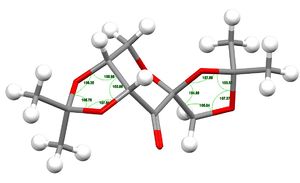

For Compound 21, two hitlists, NELQEA amd NELQEA01, were obtained. The former is not analysed because the anomeric effect (explained later) in this crystal structure is less pronounced. Thus, the NELQEA01 hitlist is chosen and the relevant structures and data are presented and analysed below in Table 7.

| Shi catalyst (NELQEA01 hitlist) | |||||

| Compound with labelled bond distances |

| ||||

| Compound with labelled bond angles |

| ||||

| Jmol file |

| ||||

| Compound with labelled atoms |

| ||||

| Bond distances /Å | C1-C8 | 1.511 | |||

| C1-C9 | 1.500 | ||||

| C7-C10 | 1.508 | ||||

| C7-C11 | 1.503 | ||||

| C1-O1 | 1.428 | ||||

| C1-O2 | 1.456 | ||||

| C2-O1 | 1.437 | ||||

| C3-O2 | 1.415 | ||||

| C3-C4 | 1.533 | ||||

| C4-O6 | 1.207 | ||||

| C5-O3 | 1.415 | ||||

| C5-C6 | 1.521 | ||||

| C5-O4 | 1.423 | ||||

| C6-O5 | 1.429 | ||||

| C7-O4 | 1.454 | ||||

| C7-O5 | 1.423 | ||||

| Bond angles /° | O1-C1-O2 | 105.78 | |||

| C1-O2-C3 | 107.81 | ||||

| O2-C3-C2 | 103.80 | ||||

| C3-C2-O1 | 100.99 | ||||

| C2-O1-C1 | 108.25 | ||||

| O4-C7-O5 | 103.59 | ||||

| C7-O5-C6 | 107.37 | ||||

| O5-C6-C5 | 105.04 | ||||

| C6-C5-O4 | 104.96 | ||||

| C5-O4-C7 | 107.59 | ||||

There are three anomeric centres in Compound 21 with carbon centres at C1, C5 and C7.

The anomeric effect is a phenomenon where there is lone pair donation from one oxygen atom to the σ*C-O orbital of the other oxygen atom, termed σLpO/σ*C-O conjugation, leading to the shortening of the first C-O bond and the lengthening of the second C-O bond. This effect is especially pronounced for the anomeric centres at C1 and C7, where one C-O bond is significantly shortened and the other is significantly lengthened compared to a typical C-O bond of 1.420 Å (ether) or 1.427 Å (alcohol)[8].

Upon a closer examination of the crystal structure of the compound, it is clear that the three atoms in each of the O1-C1-O2 and O4-C7-O5 substructures can be aligned in such a way where the σLpO and σ*C-O orbitals are anti-periplanar with respect to each other. This allows good overlap of the σLpO and σ*C-O orbitals, leading to a good and large extent of σLpO/σ*C-O conjugation. Thus, one of the C-O bonds would be shorter than expected due to a larger extent of bonding interaction or overlap between carbon and oxygen atoms, whereas the other C-O bond would be longer than expected as electron density from the first oxygen atom is donated into the antibonding σ* orbital.

However, this effect is not observed for the anomeric centre at C5 and the C5-O3 and C5-O4 bond distances are about the same as a typical C-O bond distance. This could be because the σLpO orbitals of O3 and O4 are quite nicely aligned to the σ*C=O orbitals and after such lone pair donation, there is insufficient electron density for donation to the other C-O bond, and hence no anomeric effect is observed.

It is also interesting to note that the O1-C1-O2 and O4-C7-O5 bond angles are smaller than the ideal sp3 angle of 109.5 °. This is probably because of the anomeric effect, in which there are strengthened C1-O1 or C7-O5 bonds and weakened C1-O2 or C7-O4 bonds, meaning that there is greater overlap between these orbitals, leading to a contraction in bond angle. Furthermore, the bond angles centered on oxygen atoms, such as C2-O1-C1, C1-O2-C3, C5-O4-C7 and C7-O5-C6, are all smaller than the ideal sp2 angle of 120 ° because oxygen possesses two lone pairs and according to VSEPR theory, lone pair-lone pair repulsion is larger than bond pair-bond pair repulsion, hence, there is a smaller bond angle than 120 ° as the lone pairs occupy larger space spatially.

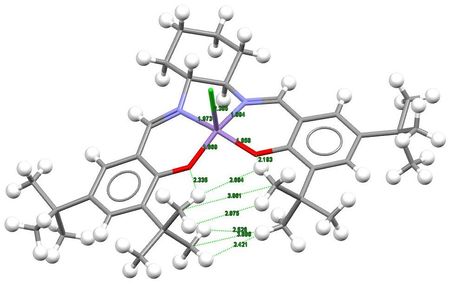

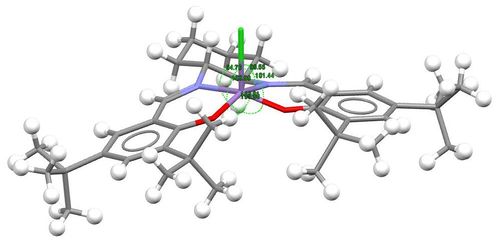

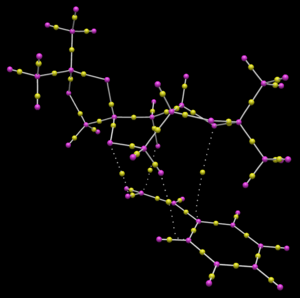

Jacobsen catalyst (Compound 23)

For Compound 23, five hitlists, TOVNIB, TOVNIB01, TOVNIB02, WEWZUU and WULJAP, were obtained. The last 2 hitlists were not analysed as they do not correspond to the structure of Compound 23, and TOVNIB was not analysed because it does not return any results. Out of TOVNIB01 and TOVNIB02, the latter was not chosen as it has 2 Me groups of some tBu groups perfectly elicpsed with each other resulting in a less stable compound. Thus, the TOVNIB01 hitlist is chosen and the relevant structures and data are presented and analysed below.

| Jacobsen catalyst (TOVNIB01 hitlist) | ||||||

| Compound with labelled bond distances |

| |||||

| Compound with labelled bond angles |

| |||||

| Jmol file |

| |||||

| Compound with labelled atoms |

| |||||

| Bond distances /Å (through space interactions for some as they are not bonds) |

CCDC value | Literature value[9] | ||||

| Mn2-Cl1 | 2.385 | 2.36 | ||||

| Mn2-N16 | 1.973 | 1.951 | ||||

| Mn2-N17 | 1.994 | 2.003 | ||||

| Mn2-O3 | 1.869 | 1.872 | ||||

| Mn2-O4 | 1.858 | 1.848 | ||||

| O3...H5 | 2.335 | - | ||||

| O4...H8 | 2.193 | - | ||||

| H5...H8 | 2.694 | - | ||||

| C6...C9 | 3.861 | - | ||||

| H7...H10 | 2.975 | - | ||||

| H11...H14 | 2.526 | - | ||||

| C12...C15 | 3.696 | - | ||||

| H13...H14 | 2.421 | - | ||||

| Bond angles /° | N17-Mn2-O3 | 155.90 | 167.1 | |||

| O4-Mn2-N16 | 163.01 | 147.0 | ||||

| N17-Mn2-Cl | 99.55 | 103.8 | ||||

| N16-Mn2-Cl | 94.76 | 94.5 | ||||

| O4-Mn2-Cl | 101.44 | 97.9 | ||||

| O3-Mn2-Cl | 103.99 | 108.5 | ||||

With 5 substituents on the Mn centre, it might be expected that Compound 23 adopts a trigonal bipyramidal or square pyramidal structure. However, from the crystal structure obtained, the complex in fact adopts a puckered square pyramidal structure.

It is known that maximum H...H attraction occurs at 2.4 Å and this interaction becomes repulsive when the distance is less than 2.1 Å, maximum C...C attraction occurs at 3.2 Å and maximum O...H attraction occurs at 2.62Å.[10] Although the 2 large tBu groups look very close in two dimensions, closer examination of the crystal structure reveals the fact that these tBu groups are not actually that close in three dimensions with H...H and C...C distances further than the distance that leads to repulsive interaction.

In fact, there are some favourable attractions between H11 and H14, H13 and H14; however, such attraction is absent between H8 and H10, H7 and H10 as these hydrogen atoms are further away from each other. There is also absence of attraction between C6 and C9, C12 and C15 as these carbon atoms are too far away from each other. Also, as the tBu groups are actually relatively far away from each other, there is no repulsive interaction between the two large and bulky groups. Furthermore, the O3...H5 and O4...H8 distances are smaller than 2.62 Å, meaning that there is some form of attraction between the two atoms. All these favourable interactions help to stabilise the compound.

The crystal structure of Jacobsen catalyst was reported by Pospisil et al.[9] and there is close agreement between experimental bond distances for data available and the computed values. There is a larger difference for bond angles between calculated and literature values and in the actual experimental crystal structure, the geometry with respect to the manganese atom is even more puckered as compared to that found in the CCDC. This could be because the computation underestimated the extent of steric bulk of the ligands and hence predicted a structure that is closer to square pyramidal than expected.

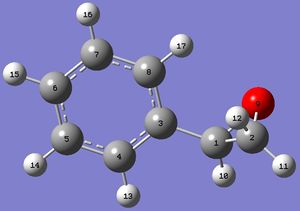

NMR spectra of epoxides

After energy optimisation, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of styrene oxide and methylstyrene oxide are computed using Avogadro. The spectra and spectral data are presented below in Tables 9-12. In each spectrum, the solvent used was chloroform. Note that the configuration of the compound does not affect its NMR spectra. For example, R-styrene oxide and S-styrene oxide will give the same NMR spectra.

1H NMR spectrum of styrene oxide

| 1H NMR chemical shift /ppm | ||||||||

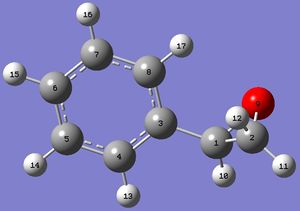

Figure 7a. Styrene oxide with labelled atoms. |

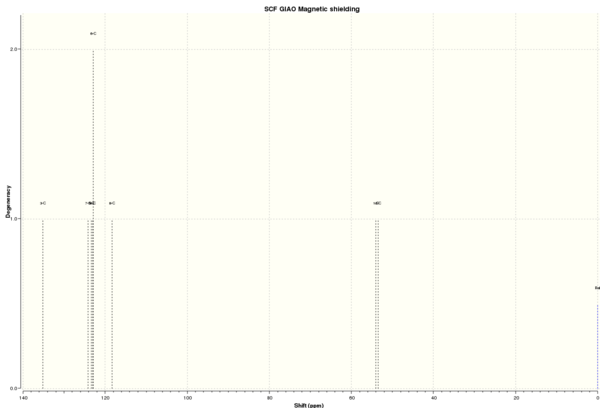

DOI:10042/26540 To enlarge the spectrum, click on the spectrum. | |||||||

| Atom number |

Calculated value |

Literature value (1)[11] |

Literature value (2)[12] |

Largest absolute difference |

Calculated integration |

Literature integration[11][12] | ||

| 13-16 | 7.49 | 7.22-7.42 | 7.27-7.34 | 0.15 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 17 | 7.30 | 1 | ||||||

| 10 | 3.66 | 3.92 | 3.84 | 0.26 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 11 | 3.12 | 3.20 | 3.13 | 0.08 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 12 | 2.54 | 2.87 | 2.81 | 0.33 | 1 | 1 | ||

From Table 9, it is clear that there is only a small and negligible difference (≤0.26) between calculated and literature values of 1H chemical shifts. Hence, it can be concluded that the computation is successful.

13C NMR spectrum of styrene oxide

| 13C NMR chemical shift /ppm | ||||||||

Figure 7b. Styrene oxide with labelled atoms. |

DOI:10042/26540 To enlarge the spectrum, click on the spectrum. | |||||||

| Atom number |

Calculated value |

Literature value (1)[11] |

Literature value (2)[12] |

Largest absolute difference |

Calculated integration |

Literature integration (assumed)[11][12] | ||

| 3 | 135.13 | 125.5, 128.2, 128.5, 137.6 |

125.5, 128.1, 128.5, 137.6 |

7.23 | 1 | 6 | ||

| 7 | 124.13 | 1 | ||||||

| 5 | 123.41 | 1 | ||||||

| 4, 6 | 122.96 | 2 | ||||||

| 8 | 118.27 | 1 | ||||||

| 1 | 54.06 | 52.4 | 52.4 | 1.66 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 53.47 | 51.3 | 51.2 | 2.27 | 1 | 1 | ||

From Table 10, most of the data agree well with literature values with a small and negligible difference of ≤1.66. However, the chemical shifts for the aryl carbon atoms differ by quite a large extent as compared to literature values and there are also a larger number of peaks than experimentally observed. This could be because the computation calculated the chemical shift of each individual carbon atom at a 'frozen' instant, whereas in real life, the carbon atom signals might be averaged out. Overall, it can be concluded that the computation is successful.

1H NMR spectrum of methylstyrene oxide

| 1H NMR chemical shift /ppm | ||||||||

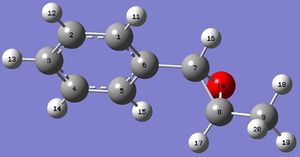

Figure 8a. Methylstyrene oxide with labelled atoms. |

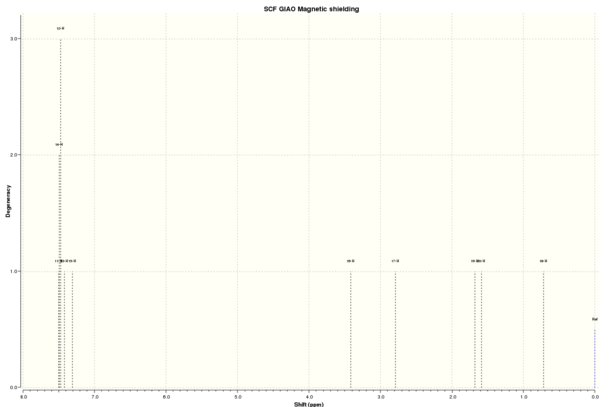

DOI:10042/26539 To enlarge the spectrum, click on the spectrum. | |||||||

| Atom number |

Calculated value |

Literature value (1)[12] |

Literature value (2)[13] |

Largest absolute difference |

Calculated integration |

Literature integration[12][13] | ||

| 11, 12, 14 | 7.49 | 7.22-7.32 | 7.24-7.34 | 0.15 | 3 | 5 | ||

| 13 | 7.42 | 1 | ||||||

| 15 | 7.31 | 1 | ||||||

| 16 | 3.41 | 3.55 | 3.56 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 17 | 2.79 | 3.10 | 3.00-3.05 | 0.31 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 19 | 1.68 | 1.42 | 1.44 | 0.72 | 1 | 3 | ||

| 20 | 1.59 | 1 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.72 | 1 | ||||||

From Table 11, it is clear that there is only a small and negligible difference (≤0.31) for most chemical shifts between calculated and literature values. Although there seems to be a large difference of chemical shifts for atoms 18-20, this is not true. This is because the computation gives three separate chemical shifts depending on the exact location of each hydrogen atom at one instant, whereas in real life, there is sufficient energy at room temperature to overcome the C-C rotation barrier and these three hydrogen atoms are in fact chemically and magnetically equivalent. The three separate signals are thus averaged to give a value of either 1.42 or 1.44, which is sufficiently close to computed value of 1.33. Hence, it can be concluded that the computation is successful.

13C NMR spectrum of methylstyrene oxide

| 13C NMR chemical shift /ppm | ||||||||

Figure 8b. Methylstyrene oxide with labelled atoms. |

DOI:10042/26539 To enlarge the spectrum, click on the spectrum. | |||||||

| Atom number |

Calculated value |

Literature value (1)[12] |

Literature value (2)[13] |

Largest absolute difference |

Calculated integration |

Literature integration (assumed)[12][13] | ||

| 6 | 134.98 | 125.5, 128.0, 128.4, 137.9 | 125.5, 128.0, 128.4, 137.7 | 7.01 | 1 | 6 | ||

| 4 | 124.07 | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 123.33 | 1 | ||||||

| 1 | 122.80 | 1 | ||||||

| 3 | 122.73 | 1 | ||||||

| 5 | 118.49 | 1 | ||||||

| 8 | 62.32 | 59.5 | 59.5 | 2.82 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 7 | 60.58 | 59.0 | 59.0 | 1.58 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 9 | 18.84 | 18.0 | 17.9 | 0.84 | 1 | 1 | ||

Note: calculated and literature values of integration are 1 carbon atom per signal.

From Table 12, most of the data agree well with literature values with a small and negligible difference of ≤2.82. However, as explained above for the 13C NMR spectrum of styrene oxide, the 13C chemical shifts for the aryl carbon atoms in methylstyrene oxide also differ by quite a large extent as compared to literature values and there are also a larger number of peaks than experimentally observed. Overall, it can be concluded that the computation is successful.

Assignment of the absolute configuration of the epoxides

The NMR spectra do not differentiate between compounds of different configurations. Therefore, to assign the absolute configuration of the epoxides, three chiroptical properties can be investigated. Firstly, with the knowledge that enantiomers have optical rotation value (at a specific wavelength) of the same magnitude but opposite sign, computations are performed to obtain optical rotation data for each enantiomer. Secondly, the Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD), rather similar to UV/Visible spectroscopy but with the use of polarised light, can be useful for other compounds but not these epoxides as there are no appropriate chromophores for epoxides. Lastly, the Vibrational Circular Dichroism (VCD), akin to IR spectroscopy with the use of polarised light, can also be used as different enantiomers will absorb the polarised light to different extent, giving rise to a VCD spectrum.

The epoxides can exist in the following configurations, as shown in Figure 9.

Optical rotation

The optical rotation data at 589 nm with chloroform as solvent are computed for each enantiomer of styrene oxide and trans-β-methylstyrene oxide and the results are presented below.

| Optical rotation /° | |||

| Computed value | Literature values | Absolute difference | |

| (R)-styrene oxide | -30.31 DOI:10042/26551 |

-23.7[14] -24.0[15] |

6.61 6.31 |

| (S)-styrene oxide | +30.43 DOI:10042/26550 |

+28.0[11] +32.1[16] |

2.43 1.67 |

| (R,R)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide | +46.77 DOI:10042/26552 |

+45.7[17] +47[18] |

1.07 0.23 |

| (S,S)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide | -46.78 DOI:10042/26553 |

-46.9[19] -43.6[20] |

0.12 3.18 |

| (R,S)-cis-β-methylstyrene oxide | -37.00 DOI:10042/26582 |

-37.8[21] -40.8[22] |

0.8 3.8 |

| (S,R)-cis-β-methylstyrene oxide | +37.40 DOI:10042/26581 |

+38.6[20] +43.8[22] |

1.2 6.4 |

From Table 13, it is clear that there is close agreement between computed and literature values of optical rotation at 589 nm, the biggest deviation being 6.61 where the possible reasons of deviation will be explained later. More importantly, to show that a certain enantiomer is created and subjected to computational analyses, the sign of the computed values should agree with that of the literature values in each case. From Table 13, it is clear that the sign of the optical rotation value computed is the same as the literature values in each case. This means that the computations are successful.

However, it is important to note how a Reaxys search reveals a surprisingly large number of errors in the literatures. For example, a patent by inventor Y. Shi reveals an optical rotation value of -47.8[19] for (R,R)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide at 589 nm at 25 °C with chloroform as solvent. This is the only literature which gives a negative optical rotation value among the 20 hits obtained from Reaxys even with different solvent, wavelength and temperature used. This example shows how literature values cannot be trusted entirely without further probe and cross referencing with other literature values.

As optical rotation data are obtained by measuring the extent by which the compound rotates a plane of polarised light, even a slight difference in conformation of a compound will result in different values obtained. This difference could be magnified with the use of different solvents, wavelengths and temperatures. For example, using a different solvent, the conformation of the compound will be slightly altered depending on the extent of interaction with the solvent. Or at a higher temperature, the compound will have a slightly larger amount of energy and this might cause a different bond position or orientation due to bond flipping or rotation processes. Therefore, for most literature values quoted apart from one (where the temperature at the point of optical rotation data collection was 26 °C), optical rotation data were collected at 589 nm at 25 °C with chloroform as solvent. Also, since enantiomeric excess affects optical rotation data directly as different enantiomers absorb polarised light to different extents, a sample of product albeit with a slight contamination of the other enantiomer will greatly affect the optical rotation values obtained, and this could contribute to a large deviation in literature values.

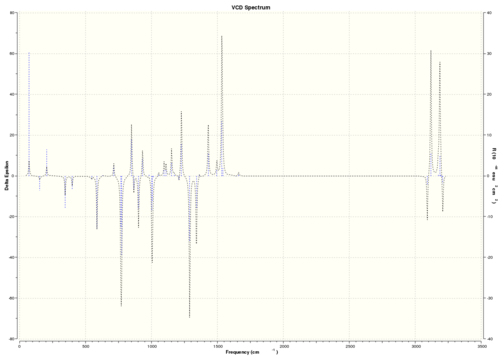

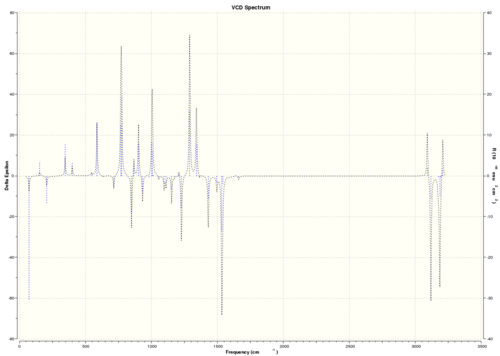

Vibrational Circular Dichroism (VCD)

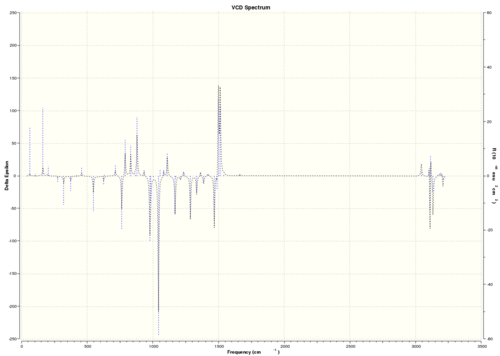

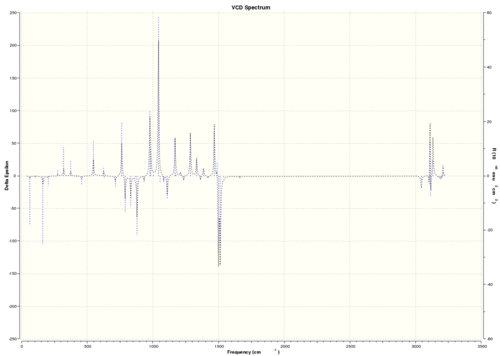

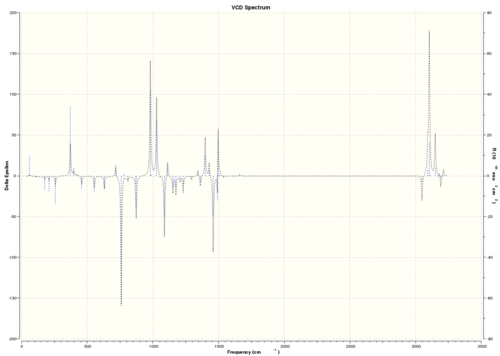

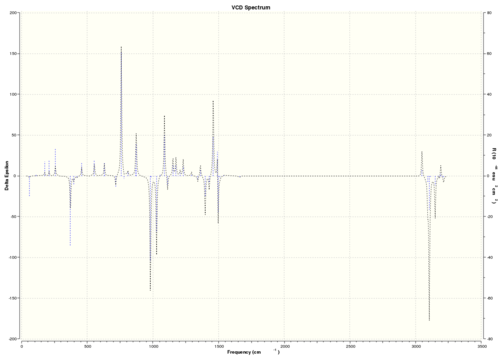

The VCD spectra are computed for each enantiomer of styrene oxide and trans-β-methylstyrene oxide and the results are presented below.

| VCD Spectrum | |

| (R)-styrene oxide |  DOI:10042/26621 |

| (S)-styrene oxide |  DOI:10042/26620 |

| (R,R)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide |  DOI:10042/26619 |

| (S,S)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide |  DOI:10042/26618 |

| (R,S)-β-methylstyrene oxide |  DOI:10042/26617 |

| (S,R)-β-methylstyrene oxide |  DOI:10042/26616 |

As VCD is a relatively new and expensive technique, there is insufficient, or no, data or literature values to compare with. However, it can be seen that the enantiomers produce peaks at the same frequencies but the sign of the intensities is different. For instance, (R)-styrene oxide produces a strong peak at 1550 cm-1 in the positive intensity axis, whereas (S)-styrene oxide produces the same peak at 1550 cm-1 in the negative intensity axis. The magnitude of intensity for each peak is the same for the enantiomers (but with different signs), and this is because the calculations are theoretical predictions. In real life, there might be other complications which result in a slightly or negligibly different result. However, there is no data for comparison purposes yet.

Transition state of the reactions

Free energies of the transition states can be used to check the enantiomeric assignment of compounds. The transition state with the lowest free energy for each enantiomer is identified, K is calculated after obtaining the free energy difference (by subtracting the free energy of the second epoxide from the first) and this value of K is manipulated to obtain the enantiomeric excess of one enantiomer over the other. The results for each pair of epoxide is summarised below in Table 15.

| Catalyst | Compound | Lowest free energy /Hartree |

Free energy difference /Hartree |

Free energy difference /kJmol-1 |

K | Enantiomeric excess (ee) /% |

Literature ee /% |

| Shi catalyst | (R,R)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide | -1343.032443 | 0.007701 | 20.218977 | 0.0002856 | 99.94 | 95.5[23] |

| (S,S)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide | -1343.024742 | ||||||

| (R)-styrene oxide | -1303.738044 | -0.000459 | -1.205104592 | 1.6264594 | 23.85 | 24.3[23] | |

| (S)-styrene oxide | -1303.738503 | ||||||

| Jacobsen catalyst | (S,R)-cis-β-methylstyrene oxide | -3383.259559 | 0.008499 | 22.3141262 | 0.0001226 | 99.98 | 84[24] |

| (R,S)-cis-β-methylstyrene oxide | -3383.251060 | ||||||

| (S,S)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide | -3383.262481 | 0.008137 | 21.3636951 | 0.0001799 | 99.96 | 92[25] | |

| (R,R)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide | -3383.254344 | ||||||

| (S)-styrene oxide | -3343.969197 | 0.007035 | 18.4703939 | 0.0005785 | 99.88 | 57[26] 59[27] | |

| (R)-styrene oxide | -3343.962162 |

In each case, the catalyst has an enantioselectivity for a specific alkene, leading to the formation of the underlined epoxide based on comparison of enantiomeric excess values.

For each pair of epoxide, the more stable compound is the one with a lower free energy; hence, the more stable epoxides are (R,R)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide, (S)-styrene oxide for Shi epoxidation and (S,R)-cis-β-methylstyrene oxide, (S,S)-trans-β-methylstyrene oxide, (S)-styrene oxide for Jacobsen epoxidation.

From Table 15, based on the calculated enantiomeric excess values, it is clear that the catalysts have enantioselectivity for one of the enantiomers of each alkene and the resulting epoxides are underlined. This means that the catalysts preferentially react with this specific alkene enantiomer, giving rise to a specific epoxide, and this is most probably due to better orbital overlaps and/or covalent and non-covalent interactions between the catalyst and the enantiomer.

The enantiomeric excess values calculated mostly agree well with literature values. Albeit with different absolute values, in most of the cases, the deviation is small and acceptable. More importantly, the enantioselectivity of catalysts calculated for each pair of epoxide is confirmed by comparison with literature reported by Shi and Jacobsen. Hence, it can be concluded that the computations are largely successful.

However, although both calculated and literature enantiomeric excess values indicate that the Jacobsen catalyst prefers to react with (R)-styrene, there is a large deviation between calculated and literature values. Strangely, when the procedures of Jacobsen epoxidation originally reported by Jacobsen were followed, an enantiomeric excess value of 57 % was obtained, and this is even more peculiar as when the reaction condition was changed to -78 °C and the reaction included m-CPBA as an oxidant, an enantiomeric excess value of 59 %, which was very similar to that of the original procedures', was obtained. This means that the enantioselectivity of Jacobsen catalyst for this pair of alkenes is not as high as in other cases and the deviation could be because the computations over-estimated certain covalent or non-covalent interactions in the transition state of (R)-styrene oxide.

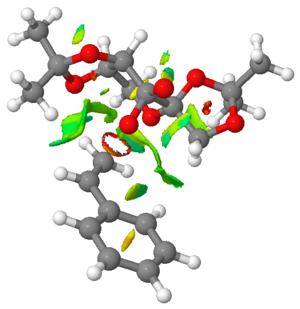

Non-covalent interactions (NCI) analysis

To investigate the properties of the transition state, the same transition state for Shi epoxidation of (R)-styrene as above is subjected to NCI analysis. Then, to illustrate the difference between the extent of non-covalent interactions in the transition state for different enantiomers, the transition state for Shi epoxidation of (S)-styrene is also subjected to NCI analysis. The NCI analysis reveals information about and extent of various non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bond and electrostatic attractions. The colour of regions indidates different extent of such interactions, with blue meaning strongly attractive, green mildly attractive, yellow mildly repulsive and red strongly repulsive.

The outcome of the NCI analysis of the transition states for Shi epoxidation of (R)- and (S)-styrene is shown below in Table 16.

| Transition state | ||

| (R)-styrene | (S)-styrene | |

| Figure |  |

|

Firstly, for the transition state for (R)-styrene, the region with the predominantly red ring indicates the region where a bond is formed in the transition state. This lies between the oxygen atom and the alkene, showing exactly where the bond formation and breaking processes happen during the alkene epoxidation reaction with the use of the Shi catalyst. The fact that this ring is red indicates that the interaction between the oxygen atom and the alkene are rather strongly repulsive, and this could be due to the electron-electron repulsion between electron-rich alkene, due to pi electron delocalisation into the phenyl ring, and the lone pair on oxygen atom. Furthermore, it is clear that the oxygen atom on Shi catalyst approaches the alkene from the top face, or rather the Re face, leading to the formation of (R)-styrene oxide via syn addition to the alkene and highlighting the stereoselectivity of the Shi catalyst.

Moreover, there are many parts throughout this transition state with mildly attractive interactions indicated by green regions. For instance, there is a large attractive interaction (indicated by a large green region) between the hydrogen atoms on the phenyl ring and those attached to the carbon atom in the 5 membered ring. There is also another large attractive interaction between the alkenyl hydrogen and hydrogen atom on the methyl group (towards the left of the image). These interactions, coupled with a few more, help to stabilise the transition state. Overall, the transition state is stabilised with multiple large and attractive interactions that override the effect of small repulsive interactions.

It is interesting to note that the phenyl ring is oriented exo with respect to the Shi catalyst. In other words, there are no favourable non-covalent interactions between the phenyl ring and any part of the Shi catalyst. This could be due to the large size of the phenyl ring, which tends to minimise steric repulsion by avoiding the Shi catalyst entirely in this particular transition state, and the pi electron repulsion between phenyl ring and other atoms of the Shi catalyst.

For the transition state for (S)-styrene, a similar red ring or region is observed where the bond is formed in the transition state. There are also many green regions indicating mildly attractive non-covalent interactions between or within atoms in the two compounds. The biggest difference between the two transition states is the extent of non-covalent interactions and there is a much larger extent of non-covalent interactions in the transition state for (S)-styrene. Most notably, the phenyl ring participates in such interactions and these interactions greatly stabilise the transition state for Shi epoxidation. If the extent of non-covalent interactions is larger in any possible transition states of Shi epoxidation of (S)-styrene as compared to those of (R)-styrene, it means that the Shi catalyst will prefer to react with (S)-styrene due to a larger extent of interactions, giving rise to the stability of the transition states formed and the catalyst's enantioselectivity.

However, from Table 15, it is clear that the Shi catalyst has a preference to react with (R)-styrene, leading to the formation of (R)-styrene oxide. This could be because overall, there is a larger extent of non-covalent interactions in the most stable transition state of (R)-styrene oxide compared to that of (S)-styrene oxide, whereas in this NCI analysis, only one each of the transition states of (R)- and (S)-styrene is compared.

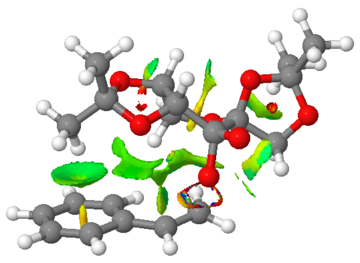

Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) analysis

To complement the NCI analysis, the same transition states for Shi epoxidation of (R)- and (S)-styrene as above are subjected to QTAIM analysis. The QTAIM analysis shows the distribution of electron density in the transition state between covalent bonds and non-covalent interactions. The result of the QTAIM analysis is shown below in Table 17.

| Transition state | ||

| (R)-styrene | (S)-styrene | |

| Figure |  |

|

From the analysis of (R)-styrene, it is interesting to note that only one of the oxygen atoms in the dioxirane group participates in non-covalent interactions with carbon atoms either on another part of the Shi catalyst or on (R)-styrene. The other oxygen atom does not participate in any form of interactions with any atoms and this is most probably because it is located far away from many atoms for any meaningful interactions. In the case where the oxygen atom of the dioxirane forms a weak non-covalent interaction with the carbon atom on (R)-styrene, it is interesting to note that it does not have such favourable interactions with both alkenyl carbon atoms at the same time. This is probably because the oxygen-carbon bonds of the epoxide are asynchronously formed.

There are also many other weak non-covalent interactions between atoms from Shi catalyst and (R)-styrene. For instance, the hydrogen atom of one of the methyl rings (towards the left of the image) forms weak non-covalent interactions with a hydrogen atom on the alkene. There is also a weak O...H interaction between one oxygen atom of the 5 membered ring and another hydrogen atom on the alkene. These interactions help to stabilise the transition state, aiding the process of epoxide formation.

For (S)-styrene, there is also only interaction between one of the oxygen atoms in the dioxirane group and one of the alkenyl carbon atoms. There is also an intermolecular O...H interaction formed between the oxygen atom in the 6 membered ring and one of the alkenyl hydrogen atoms. These interactions help to stabilise the transistion state, but overall, there is a smaller extent of interactions between (S)-styrene and Shi catalyst in the transition state for (S)-styrene as compared with that for (R)-styrene. This might mean that there is a smaller tendency to form this transition state for the Shi epoxidation of (S)-styrene.

Suggestions for new candidates for investigations

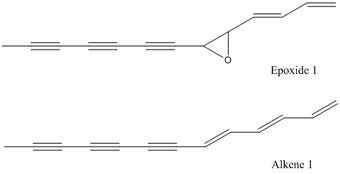

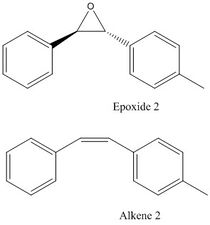

Reaxys is used to search for epoxides with optical rotatory power of less than -500° or more than 500° and the structures of two of the epoxides and their corresponding alkene are presented below in Table 18.

| 2-buta-1,3-dienyl-3-hepta-1,3,5-triynyl-oxirane | Trans-(2R,3R)-2-(4-methylphenyl)-3-phenyl oxirane | |

| Figures |  |

|

| Wavelength /nm | 365 | 436 |

| Temperature /°C | 20 | not reported |

| Optical rotation /° | -718[28] | -580[29] |

The two epoxides have optical rotatory power of -718 ° and -580 ° respectively according to the literature. However, the optical rotatory power data for epoxide 1 is only reported by one literature, whereas for epoxide 2, it is only reported by one literature using a wavelength of 436 nm. In each case, the corresponding alkenes are not commercially available (not found in Sigma-Aldrich but available from less well-known online suppliers). With limited commercial availability and unknown toxicity, these epoxides are hard to be incorporated in lab synthesis projects. They might be of a slightly greater use in computational projects; however, there is limited literature data to make comparison with.

Conclusion

Through this two week computational exercise, various computational techniques are developed and explored, such as energy optimisation, optical rotatory power, VCD and NMR spectra computation, crystal structure search, NCI and QTAIM analysis. These techniques have proven to be very effective and successful in predicting various properties of compounds, such as the relative stability of isomers, absolute configurations of compounds and enantioselectivity of catalysts. There is also good agreement with literature values for most, if not all, computations performed. Results discussion would have been more interesting if there were more time to fully characterise epoxides obtained in the complementary experiment 1S.

References

- ↑ M. A. Fox, R. Cardona, N. J. Kiwiet, "Steric Effects vs. Secondary Orbital Overlap in Diels-Alder Reactions. MNDO and AM1 Studies.", J. Org. Chem., 1987, 52, 1469–1474. DOI:10.1021/jo00384a016

- ↑ P. Caramella, P. Quadrelli, L. Toma, "An Unexpected Bispericyclic Transition Structure Leading to 4+2 and 2+4 Cycloadducts in the Endo Dimerization of Cyclopentadiene.", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 1130–1131. DOI:10.1021/ja016622h

- ↑ D. Skála , J. Hanika , "Kinetics of dicyclopentadiene hydrogenation using Pd/C catalyst", Petroleum and Coal, 2003, 45, 105-108.

- ↑ S. W. Elmore, L. A. Paquette, "The first thermally-induced retro-oxy-cope rearrangement", Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 32, 319-322. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ J. Bredt, "Über sterische Hinderung in Brückenringen (Bredtsche Regel) und über die meso-trans-Stellung in kondensierten Ringsystemen des Hexamethylens", Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie, 1924, 437, 1-13. DOI:10.1002/jlac.19244370102

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 W. F. Maier, P. V. R. Schleyer, "Evaluation and prediction of the stability of bridgehead olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891-1900. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 L. A. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, "[3.3] Sigmatropy within 1-vinyl-2-alkenyl-7,7-dimethyl-exo-norbornan-2-ols. The first atropselective oxyanionic Cope rearrangement.", J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1990, 122, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ G. Glockler, "Carbon-oxygen bond energies and bond distances", J. Phys. Chem., 1958, 62, 1049–1054. DOI:10.1021/j150567a006

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 P. J. Pospisil, D. H. Carsten, E. N. Jacobsen, "X-Ray Structural Studies of Highly Enantioselective Mn(salen) Epoxidation Catalysts", Chemistry - A European Journal, 1996, 2, 974–980. DOI:10.1002/chem.19960020812

- ↑ H. Rzepa, "Conformational Analysis", 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 K. Huang, H. Wang, V. Stepanenko, M. D. Jes, C. Torruellas, W. Correa, M. Ortiz-marciales, "Chiral Epoxides via Borane Reduction of 2-Haloketones Catalyzed by Spiroborate Ester : Application to the Synthesis of Optically Pure 1,2-Hydroxy Ethers and 1,2-Azido Alcohols", J. Org. Chem., 2013, 76, 1883–1886. DOI:10.1021/jo102294j

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 L. Ji, Y.-N. Wang, C. Qian, X.-Z. Chen, "Nitrile-Promoted Alkene Epoxidation with Urea-Hydrogen Peroxide (UHP)", Syn. Comm., 2013, 43, 2256–2264. DOI:10.1080/00397911.2012.699578

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 K. a. Stingl, K. M. Weiß, S. B. Tsogoeva, "Asymmetric vanadium- and iron-catalyzed oxidations: new mild (R)-modafinil synthesis and formation of epoxides using aqueous H2O2 as a terminal oxidant", Tetrahedron, 2012, 68, 8493–8501. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2012.07.052

- ↑ D. E. White, E. N. Jacobsen, "New oligomeric catalyst for the hydrolytic kinetic resolution of terminal epoxides under solvent-free conditions", Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2003, 14, 3633–3638. DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2003.09.024

- ↑ D. C. Forbes, S. V. Bettigeri, S. a. Patrawala, S. C. Pischek, M. C. Standen, "S-Methylidene Agents: Preparation of Chiral Non-Racemic Heterocycles", Tetrahedron, 2009, 65, 70-76. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.019

- ↑ H. Lin, J. Qiao, Y. Liu, Z.-L. Wu, "Styrene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. LQ26 catalyzes the asymmetric epoxidation of both conjugated and unconjugated alkenes", Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 2010, 67, 236–241. DOI:10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.08.012

- ↑ S. Pedragosa-Moreau, A. Archelas, R. Furstoss, "Microbiological Transformations 32: Use of Epoxide Hydrolase Mediated Biohydrolysis as a Way to Enantiopure Epoxides and Vicinal Diols: Application to Substituted Styrene Oxide Derivatives", Tetrahedron, 1996, 52, 4593–4606. DOI:10.1016/0040-4020(96)00135-4

- ↑ G. Fronza, C. Fuganti, P. Grasselli, A. Mele, "On the mode of bakers’ yeast transformation of 3-chloropropiophenone and related ketones. Synthesis of (2S)-[2-2H]propiophenone, (R)-fluoxetine, and (R)- and (S)-fenfluramine", J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 6019–6023. DOI:10.1021/jo00021a011

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Y. Shi, "Catalytic asymmetric epoxidation", 2004, United States.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 S. Koya, Y. Nishioka, H. Mizoguchi, T. Uchida, T. Katsuki, "Asymmetric epoxidation of conjugated olefins with dioxygen", Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2012, 51, 8243–6. DOI:10.1002/anie.201201848

- ↑ O. A. Wong, B. Wang, M.-X. Zhao, Y. Shi, "Asymmetric epoxidation catalyzed by alpha,alpha-dimethylmorpholinone ketone. Methyl group effect on spiro and planar transition states", J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74, 6335–6338. DOI:10.1021/jo900739q

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 B. Wang, O. A. Wong, M.-X. Zhao, Y. Shi, "Asymmetric epoxidation of 1,1-disubstituted terminal olefins by chiral dioxirane via a planar-like transition state", J. Org. Chem., 2008, 73, 9539–9543. DOI:10.1021/jo801576k Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "jo801576k" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 23.0 23.1 Z.-X. Wang , Y. Tu , M. Frohn , J.-R. Zhang , Y. Shi , "An Efficient Catalytic Asymmetric Epoxidation Method", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 11224–11235. DOI:10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ E. N. Jacobsen, W. Zhang, A. R. Muci, J. R. Ecker, L. Deng, "Highly enantioselective epoxidation catalysts derived from 1,2-diaminocyclohexane", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 11224–11235. DOI:10.1021/ja00018a068

- ↑ A. M. Daly , M. F. Renehan , D. G. Gilheany , "High Enantioselectivities in an (E)-Alkene Epoxidation by Catalytically Active Chromium Salen Complexes. Insight into the Catalytic Cycle", Org. Lett., 2001, 3, 663-666. DOI:10.1021/ol0069406

- ↑ W. Zhang, J. L. Loebach, S. R. Wilson, E. N. Jacobsen, "Enantioselective Epoxidation of Unfunctionalized Olefins Catalyzed by (Sa1en)manganese Complexes", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 2801-2803. DOI:10.1021/ja00163a052

- ↑ M. Palucki , P. J. Pospisil , W. Zhang , E. N. Jacobsen, "Highly Enantioselective, Low-Temperature Epoxidation of Styrene", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116, 9333–9334. DOI:10.1021/ja00099a062

- ↑ F. Bohlmann, C. Arndt, H. Bornowski, H. Jastrow, K.-M. Kleine, "Polyacetylenverbindungen, XXXVIII. Neue Polyine aus dem Tribus Anthemideae", Chemische Berichte, 1962, 95, 1320–1327. DOI:10.1002/cber.19620950603

- ↑ P.M. Dansette, H. Ziffer, D.M. Jerina , "Optically active 4-substituted cis-1,2-diphenylethylene oxides and related 1,2-diphenylethane diols", Tet., 1976, 32, 2071-2074. DOI:10.1016/0040-4020(76)85110-1