Rep:Mod:kmt07231

Cyclodimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

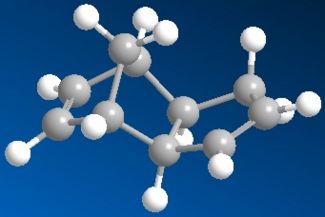

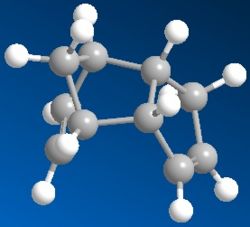

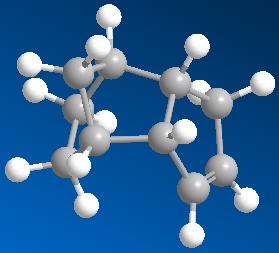

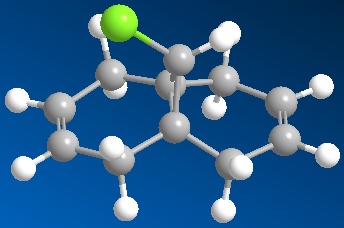

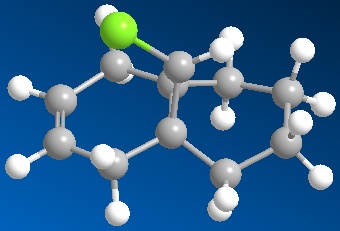

The cyclodimerisation of cyclopentadiene can give two possible products, the exo dimer 1 or the endo dimer 2. However, experimental results show that in reality, there is only one specific dimer product, which is the endo dimer 2. The exo dimer 1 has a total energy of 133.47 kJ/mol while the energy of the endo dimer product 2 is approximately 142.41 kJ/mol. Both energy values are calculated using the MM2 force field option in the ChemBio3D Ultra programme. The structures of both 1 and 2 are shown below.

The exo dimer 1 seems to be less strained as one of its 5-membered ring (pointing upwards) is pointing away from the other two rings. On the other hand, that particular 5-membered ring (pointing downwards) in the endo dimer 2 is forced near the other two rings, causing the endo dimer to be more strained and hindered. This explains the reason for the higher energy level of the endo dimer 2 and the lower energy of the exo dimer 1. As the exo dimer 1 has a lower energy, it is thermodynamically more stable and is expected to be the product of the cyclodimerisation if the reaction is under thermodynamic control.

However, the main and only product of the cyclodimerisation is the endo dimer 2 which has a higher energy level than the exo dimer 1. The product of the reaction is the kinetic product and this means that the cyclodimerisation of cyclopentadiene is kinetically controlled. There is no equilibrium between the two exo and endo dimers to obtain the thermodynamically more stable product and the reaction is irreversible. The transition state of the endo dimer 2 is expected to be at a lower energy level and it is more stable than the transition state of the exo dimer 1. Hence, the activation energy required to form the transition state of the endo dimer 2 is smaller than that for exo dimer 1, causing the endo dimer 2 to be formed much faster than the exo dimer 1, therefore making it the product of the reaction.

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

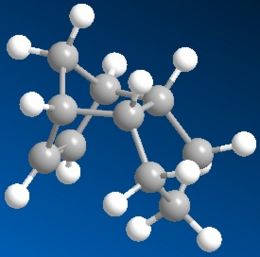

There are 2 possible hydrogenation products of the endo dimer 2 - the dihydro derivatives 3 or 4. Products 3 and 4 are different due to the different C=C double bonds involved in the hydrogenation reaction where only 1 of the 2 double bonds in the endo dimer 2 reacts with hydrogen. Using the MM2 force field option in the ChemBio3D Ultra programme to obtain the energy levels, it is found that the energy level of the dihydro derivative 3 (149.42 kJ/mol) is higher than that of the dihydro derivative 4 (130.53 kJ/mol). In a thermodynamically controlled reaction, there is an equilibrium between the 2 products (3 and 4) and the reactant (endo dimer 2) and all the reactions are reversible. The product with the lowest energy will be the most stable one and it will be the major product formed in the reaction. Therefore, if the hydrogenation reaction of dimer 2 is under thermodynamic control, product 4 will be the major product as it is more stable thermodynamically. This also means that the C=C double bond in the 6-membered ring can undergo hydrogenation more easily than the C=C double bond in the 5-membered ring to give a more stable product as product 4, which has a lower energy, does not contain a double bond in the 6-membered ring but only has a double bond in the 5-membered ring.

The stretching, bending, torsion, van der Waals and hydrogen bonding energy terms all contribute to the total energy of the products 3 and 4 under the molecular mechanics approach and all these components are assumed to be non-interacting. The hydrogen bonding contribution to the total energy and stability of products 3 and 4 is minimal and can be neglected as both 3 and 4 do not have any hydrogen bonding components in their structures. The contributions to the total energies of 3 and 4 are shown in the table below.

| Energy Component | Product 3 | Product 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch (kJ/mol) | 5.37 | 4.62 |

| Bend (kJ/mol) | 83.06 | 60.77 |

| Stretch-Bend (kJ/mol) | -3.50 | -2.29 |

| Torsion (kJ/mol) | 45.34 | 52.39 |

| Non-1,4 Van der Waals (kJ/mol) | -5.09 | -4.41 |

| 1,4-Van der Waals (kJ/mol) | 23.55 | 18.86 |

| Dipole-Dipole (kJ/mol) | 0.68 | 0.59 |

It is determined that the stretching, bending and van der Waals contributions to the total energy are higher for product 3 than product 4. In fact, the bending energy contribution to product 3 is very much larger than the contribution to product 4. Torsion is the only component that has a larger contribution to the total energy of product 4 than product 3. Overall, all these contributions have a larger effect on product 3 than product 4, causing product 3 to have a higher energy and less stable than product 4. The higher stretching and bending energies of product 3 are due to the fact that the 5-membered ring of product 3 is more crowded and there is more steric effect when stretching and bending the molecule. The higher steric effect increases the stretching and bending energies, making product 3 less stable. On the other hand, less steric effect is observed in the 5-membered ring in product 4 when stretching and bending it, hence, it is more stable than 3. A possible reason for the higher torsion of product 4 is the more substituted and crowded 6-membered ring in 4.

Nucleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring

The reaction above shows the reaction between prolinol (5) and methyl magnesium iodide to give product 6. The negatively charged methyl group can attack the pyridine at the 4 position from either the top or bottom face of the pyridine ring to give 2 possible products but the only one formed is product 6 where the methyl attacks the pyridine ring from the top face[1]. The starting reactant can have 2 possible configurations as shown below:

The structure on the left is the one labelled 5a or 5c and has the H atom pointing down while the other structure, 5b has the H atom pointing upwards. After minimisation using the MMFF94 force field, it is found that the structures with the H atom pointing down have lower energies (5a: 240.75 kJ/mol and 5c: 240.59 kJ/mol) than the other structure (5b: 247.58 kJ/mol). This means that the reactant 5 exists as a structure with the H atom pointing down as this structure is more stable. Comparing 5a and 5c, it is found that the configuration of the 5-membered proline ring and the -CH2 group around the ether O atom are quite different. Besides that, the carbonyl group in 5a is above the pyridine ring (an angle of approximately 20.5° from the pyridine ring) while the carbonyl group is about planar with the pyridine ring in 5c (angle of -1.9° which is small enough to assume that they are in fact planar)[1]. 5c is only slightly more stable than 5a due to its lower energy level. Prolinol 5 has the structure 5a with the C=O group above the ring at an angle of approximately 20.5° from the pyridine ring. The O atom of the carbonyl group will coordinate with the Mg atom of the Grignard reagent, causing the Grignard reagent to approach the pyridine ring from the top face[1]. This causes the methyl group to preferentially attack the pyridine ring from the top face instead of the bottom face and only 1 product, which is 6 is formed in this reaction. The magnesium enolate intermediate formed in the reaction is shown below[1].

The 2nd nucleophilic addition to a pyridine ring is given below. It involves the reaction between the pyridinium ring of 7 and aniline to form product 8.

There are 2 possible structures of 7 (shown below), one with the C=O group above the pyridine ring at an angle of 36.0° (7a) while the other one has the C=O group below the pyridine ring at angle of -34.3° (7b). The energy of both structures are calculated using minimisation with the MMFF94 force field. It is found that the energy of the structure with the C=O group below the pyridine ring (7b: 417.48 kJ/mol) is lower than the one with the C=O group above the pyridine ring (7a: 474.56 kJ/mol). This suggests that the most likely configuration for 7 is the one with the C=O group below the pyridine ring as it is more stable due to its lower energy level.

The nucleophilic attack of the aniline on the 4-position of the pyridine can take place from above or below the pyridine ring. As the C=O group in 7 is located below the pyridine ring (7b is the more stable structure), there will be unfavourable steric clash when the aniline approaches the pyridine ring from the bottom face for the attack on the 4-position. This causes the aniline to attack the pyridine ring of 7 from the top face only as this minimises the steric effects due to the C=O group. This means that the stereochemistry of the product 8 is controlled by the carbonyl lactam, where the aniline can only attack on the opposite face with respect to the C=O lactam[2]. Hence, the product formed, 8, has the -NHPh group on the top face (sticking up) at the 4-position of the pyridine ring.

These simple models can be improved by using other techniques such as the MM2 force-field, MOPAC interface, GAMESS interface or even the Gaussian interface to minimise the energy and find the structure with the lowest energy level. There are also many methods in the Gaussian interface which can be used, and these include the DFT (b3lyp or mpw1pw91 with different basis set, polarisation and heavy atom), HF, AM1 and other methods. These different techniques might give a slightly different structure and a different minimum energy for a same molecule as different methods consider different parameters when changing the structure and minimising the energy.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of Intermediate in Synthesis of Taxol

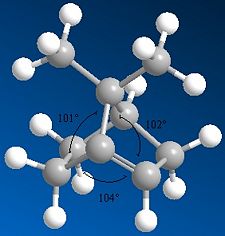

A key intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol is shown above and it has 2 possible structures, 9 or 10. Structure 9 has the carbonyl group pointing up while the carbonyl group is pointing down in structure 10. The energies of the 2 structures are minimised using molecular mechanics MM2 force-field. For structure 9, its energy is calculated to be approximately 227.72 kJ/mol while the energy of structure 10 is about 185.36 kJ/mol. The most stable isomer is the one with the lowest energy, hence, the intermediate exists as structure 10. In fact, the intermediate formed only has the structure 10 after the atropselective anionic oxy-Coperearrangement[3]. It is found that the bridgehead alkene in structure 10 is unusually stable and reacts very slowly with other reagents in subsequent functionalisation reaction of the alkene unlike typical bridgehead alkenes in cyclic systems. This is because the alkene found in intermediate 10 is a hyperstable alkene - a type of alkene that has negative olefin strain value and contains less strain that its parent hydrocarbon[4]. For small- or medium-sized bicyclic systems (5 or 6-membered rings), the bridgehead double bond is very strained (the angle around the C=C bond is much smaller than 120°), causing it to be very unstable and reactive in reactions with other reagents. However, for larger ring systems such as intermediate 10, the bridgehead alkene is unreactive due to the special stability afforded by the cage structure of the alkene[4]. The larger ring system in intermediate 10 causes the strain at the bridgehead alkene to be less severe (the angle around the C=C bond closer to 120°), giving it stability, hence the unreactiveness of the alkene in 10.

A reactive alkene :  Structure 10, a hyperstable alkene :

Structure 10, a hyperstable alkene :

In addition to that, the parent polycycloalkane (saturated form of the alkene), formed from the reaction of the alkene in intermediate 10, has a greater strain, making it less favourable for the alkene to change into the saturated, alkane form[4]. For example, the hydrogenated product of intermediate 10 (shown below) has a higher energy (292.51 kJ/mol) and has higher strain due to larger stretching, bending and torsion energies than intermediate 10, making it more unstable. In conclusion, the extra stability due to the larger ring system of 10 and the greater strain of the parent polycycloalkane cause the alkene in intermediate 10 to be very stable and unreactive.

The most stable intermediate, 10 has the carbonyl group pointing down. The 6-membered ring is in the chair conformation while the larger 10-membered ring is also in the chair conformation[3]. This combination of configurations is the one that produces the most stable isomer form of the intermediate. For 9, the 10-membered ring is in the twist-boat conformation which is not as stable as the chair conformation in 10[3]. The usage of a different force-field, MMFF94, gives different energy values for both 9 and 10. The energy of structure 9 is calculated to be 346.25 kJ/mol while the energy of structure 10 is approximately 253.60 kJ/mol. Both energies are higher than the ones obtained using the MM2 force-field, although the one for 10 remains much lower than the one for 9. This means that the structure 10 is indeed more stable than 9, regardless of the type of force-field used for the minimisation of energy.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

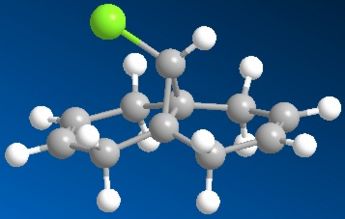

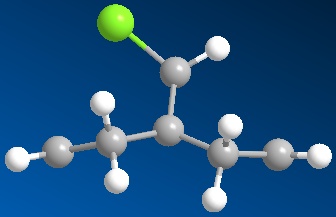

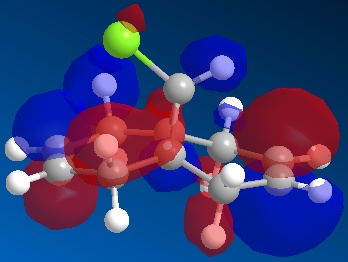

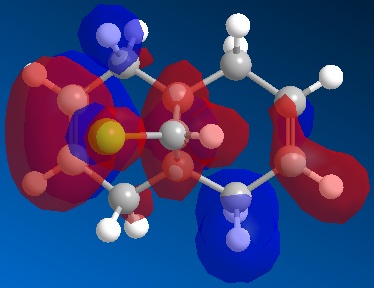

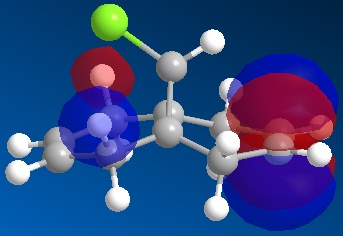

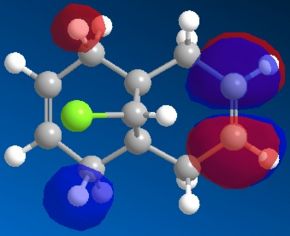

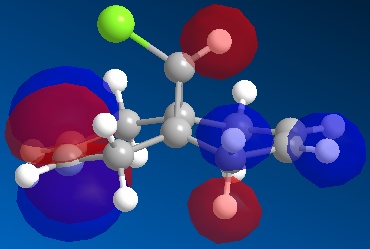

Compound 11 (shown above, on the left) has 2 6-membered rings fused together, with a bridging C atom that is bonded to a Cl atom. Minimisation using the MM2 force-field gives a structure shown above (on the centre) where the 2 6-membered rings are found to have an identical conformation. Both the 6-membered rings are slightly bent and the energy of structure 11 is calculated to be 74.94 kJ/mol. Application of the MOPAC/PM6 method on the pre-optimised structure of 11 gives a slightly different result for the structure (shown above, on the right). The 2 6-membered rings are now completely different as they have different configurations. The 6-membered ring directly below the Cl atom has a planar configuration while the other 6-membered ring which is away from the Cl atom has the bent configuration (unchanged). The heat of formation of compound 11 with this structure is given as 82.65 kJ/mol - slightly higher than the energy of the structure given by the MM2 force-field minimisation (74.94 kJ/mol). The HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 orbitals of compound 11 are obtained from the MOPAC/PM6 calculations and are shown below:

The HOMO is the molecular orbital that is most reactive towards the electrophilic attack of the dichlorocarbene. From the HOMO diagram above, it is observed that the 2 alkene bonds in compound 11 are different. The double bond that is directly below the Cl atom (endo double bond) has a large density of electrons while the other alkene (exo double bond) has less electron density[5]. This means that the endo double bond is more nucleophilic due to the higher density of electrons and is more likely to react with dichlorocarbene in the electrophilic addition reaction[5]. The exo double bond is also less reactive because there is significant stabilising overlap between the antiperiplanar Cl-C σ* orbital (LUMO+1) and the occupied exo π orbital (HOMO-1)[5]. The Cl-C σ* - exo π orbital interaction would result in a geometrical distortion of the exo double bond towards the bridgehead carbon and this is consistent with the expected structure of 11 given by the MOPAC/PM6 method[5]. Since the endo double bond is more nucleophilic, it is more reactive towards electrophile and will react with dichlorocarbene to give the product shown below[5]. In fact, the dichlorocarbene addition to compound 11 shows remarkable π-selectivity, with the syn-trichloride below the only monoadduct product isolated[6].

The vibrational frequencies of compound 11, which contains 2 double bonds (endo and exo) DOI:10042/to-3731 , are now compared to its dihydro derivative, compound 12, which only has one endo double bond (the exo double bond is replaced with a C-C single bond) DOI:10042/to-3730 .

The C-Cl stretching frequencies are observed for both compounds 11 and 12. Both peaks are strong in the IR spectrum although the C-Cl stretch is not a perfect C-Cl stretch with both the C and Cl atoms moving towards and away from each other, rather it looks more like a twist-stretch with the Cl atom not moving much while the C atom moves to stretch the bond. For compound 11, the C-Cl stretching frequency is at 771 cm-1 while the C-Cl stretching frequency is at 780 cm-1 for compound 12. A lower stretching frequency siganls a weaker C-Cl bond as less energy is required to stretch the bond. Hence, the C-Cl bond is weaker in compound 11 than the one in compound 12. This can be explained from the fact that there is electron density donation from the filled π orbital of the exo alkene bond to the empty σ* orbital of the C-Cl bond in compound 11. As electron density is added to the antibonding C-Cl σ* orbital, the C-Cl bond in compound 11 becomes weaker and has a lower stretching frequency.

The C-H stretching frequencies are very strong for both compounds; for compound 11, its range is between 3000 - 3197 cm-1 while the range for compound 12 is between 3007 - 3213 cm-1. Other peaks with large IR intensity are due to the bending of the molecule, especially the H atoms. For compound 11, a strong bending frequency is observed at 689 cm-1 while the strong bending frequencies are observed at 682 and 940.40 cm-1 for compound 12. Compound 11 has 2 C=C alkene bonds and 2 C=C stretching frequencies (which is expected) are observed: 1737 cm-1 for the exo double bond and 1757 cm-1 for the endo double bond. As the stretching frequency of the exo double bond is smaller than that of the endo double bond, this means that the exo double bond is weaker than the endo double bond. This is probably due to the overlap between the C-Cl σ* orbital and the π orbital of the exo double bond. The donation of electron density from the exo double bond to the empty C-Cl σ* orbital weakens the double bond, causing it to have a lower stretching frequency. For compound 12, there is 1 double bond and hence, only 1 stretching frequency at 1754 cm-1 is observed for the endo double bond. The stretching frequency of the endo double bond is slightly smaller in compound 12 than in compound 11, suggesting that the endo double bond is slightly weaker in compound 12.

Miniproject - Pd-Catalyzed Intramolecular 5-exo-dig Hydroarylation of N-Arylpropiolamides

The reaction shown above is an intramolecular 5-exo-dig hydroarylation of a N-arylpropiolamide where the alkyne group reacts with the benzene ring to form a 5-membered ring[7]. This reaction is catalysed using a Palladium catalyst, Pd(OAc)2, and is performed under neutral conditions as an acidic environment will result in another reaction, the 6-endo-dig cyclisation that gives only one product[7]. Toluene is used as the solvent in this reaction while dppf is the additional ligand that binds to the Pd centre in the reaction mechanism. The 5-exo-dig hydroarylation can give a product mixture of two isomers, the Z-isomer and the E-isomer due to the formation of an alkene after the formation of the 5-membered ring. The Z-isomer is the product where the phenyl group is on the same side of the double bond with the carbonyl group while these 2 groups are on the opposite side of the double bond in the E-isomer. The structure of the reactant is shown below DOI:10042/to-3713 .

Reactant |

The reactant has a structure with the carbonyl O atom pointing away from the fluoro-benzene ring, as shown above, instead of the one where the O atom is pointing towards the fluoro-benzene ring. This is because the first structure is more stable as proven by comparing the energies of the 2 possible structures after geometry minimization using the MM2 force-field. The structure given above has a lower energy (26.67 kJ/mol vs 28.52 kJ/mol), hence it is more stable and the reactant is very likely to exist as this structure. With the reactant having the above structure, it is observed that the alkyne group is located near the fluoro-benzene ring, making the 5-exo-dig cyclisation possible for the reactant. The structures of the Z- DOI:10042/to-3715 and E-isomers DOI:10042/to-3716 or DOI:10042/to-3714 are shown below.

Z-isomer:

Z-isomer |

E-isomer:

E-isomer |

or

E-isomer(2nd option) |

The Z-isomer has a structure where the phenyl group on the alkene is planar with respect to the fused 6- and 5-membered rings. The phenyl group on the double bond is not twisted and the whole Z-isomer is almost planar, except for the methyl group attached to the N atom. On the other hand, the E-isomer can have 2 possible structures, both shown above. Both structures have a very twisted phenyl group on the alkene (twist angle approximately 36° and -36°), with the only difference between them being the relative orientation of the twisting - the phenyl group is twisted in the positive direction in one of the structure while the other structure has the phenyl group twisted in the other direction. The reason for the large twist angle of the phenyl group for the E-isomer is the minimization of the steric clash between the phenyl group and the fluoro-benzene. If there is no twisting in the E-isomer, the H atoms on the phenyl will be very close to the H and F atoms on the fluoro-benzene and this gives rise to strong steric repulsions which is unfavourable as it raises the energy and destabilise the structure, hence, the phenyl group in the E-isomer is always twisted. The structures of both isomers are determined using MM2 force-field and MOPAC/AM1 methods first before the geometry is optimised further using the mpw1pw91/6-31G(d,p) DFT method.

As the phenyl group at the alkene is near to the fluoro-benzene group in the E-isomer, it is expected to have considerable steric clash (although this could be small after minimization) and the E-isomer is expected to have a higher energy. The two possible structures for the E-isomer, however, have almost the same energy as their energy difference is negligible (2.63×10-4 kJ/mol) and hence, the IR and NMR specta is expected to be about the same. The Z-isomer does not have much steric clash effect as its phenyl group on the alkene is pointing away from the other ring system and there is no other atoms which is located near the phenyl group. It is expected to have a lower energy due to the very minimal/absence of steric clash. Hence, we would expect the Z-isomer to have a lower energy than the E-isomer and the Z-isomer is predicted to be more stable than the E-isomer. The energies of both isomers are calculated using the b3lyp/6-31G(d,p) DFT method. The energy of the Z-isomer is calculated to be -2224663 kJ/mol DOI:10042/to-3717 while the energy of the E-isomer is about -2224660 kJ/mol DOI:10042/to-3718 . The Z-isomer has a lower energy than the E-isomer as predicted and this means that the Z-isomer is thermodynamically more stable than the E-isomer. However, the energy difference between the Z-isomer and the E-isomer is very small (approximately 3.06 kJ/mol). The energy level of the reactant is calculated to be about -2223950 kJ/mol DOI:10042/to-3713 , which is higher than the energies of both the Z- and E-isomers. This means that both isomer products are more stable than the reactant and the intramolecular 5-exo-dig cyclisation is a favourable reaction.

It is reported in the literature that the ratio of products formed from the reaction at 80°C is 71% Z-isomer and 22% E-isomer[7]. It is also reported that the energy of the Z-isomer is lower than the E-isomer, although the values given are for another reactant[7]. Both these statements and findings in the literature are supported by the computational energy calculations and predictions done in this experiment. Since the Z-isomer is more stable from the energy predictions, it is the thermodynamic product and will be the major product in the reaction. Some amount of E-isomer is formed in the reaction too as the energy difference between the two isomers are small (3.06 kJ/mol) and the E-isomer is not too destabilised. It is also reported in the literature that the ratio of products formed will be 26% Z-isomer and 70% E-isomer when the reaction is repeated at 140°C[7]. This means that the major product of the reaction has changed from the more stable Z-isomer to the less stable E-isomer. The explanation for this is the small energy difference between the two isomers[7]. As mentioned earlier, the E-isomer is not very destabilised and it is very easy to convert the Z-isomer to the E-isomer due to the small energy difference between them. The increase in temperature means that there is more thermal energy in the system and this increase in thermal energy can be used to change the Z-isomer to the E-isomer. This causes the E-isomer to be the major product at higher temperature. Therefore, the intramolecular 5-exo-dig cyclisation reaction under these conditions (Pd(OAc)2, dppf and toluene) shows different selectivity at different temperatures. The more stable Z-isomer will be the major product at low temperatures while the less stable E-isomer is favoured at higher temperatures.

There are 2 possible reaction mechanisms proposed for this reaction[7]. The first one is shown in the diagram below. The Pd catalyst first coordinates to the O atom of the carbony group to form A. Then, one of the the arene C-H bond (next to the C-N) is activated and broken with the help of the Pd catalyst and the complexation of the Pd catalyst to the alkyne occurs to give intermediate B. The arene C-H bond is easily activated as the Pd metal centre can interact easily with the orbitals on the arene due to the open and less hindered face of the arene. This is then followed by either the cis- or trans-addition across the alkyne to give either the (Z)-C or (E)-C intermediates. This step is the ring closing step which gives rise to two possible isomer products. The final Z-isomer and E-isomer products are then obtained from the protonation of C, with the cis and trans symmetries intact.

The second possible mechanism involves the in-situ formation of PdH(OAc)Ln from the direct reaction between the Pd catalyst and the ligand. This Pd species then reacts in the cis-hydropalladation of alkyne to give intermediate D. This is followed by the arene C-H activation step to give E, which has a new 6-membered ring due to the linkage between the Pd and the benzene and alkene C atoms. After that, the reductive elimination of D takes place to give only the Z-isomer product. The stereochemistry of the final product is determined in the cis-hydropalladation of alkyne step. As the addition is a cis-type addition to the triple bond, the Pd and the H will end up on the same side of the double bond, causing the phenyl and carbonyl groups to always be on the same side of the double bond, hence only the Z-isomer is formed.

Some spectroscopic methods can be used to try to differentiate the two isomer products. The IR spectroscopy can be used to determine the functional groups present in the product molecule allowing us to check that the products formed are indeed correct. Both the Z- and E-isomers are very similar to each other, and this causes the IR spectroscopy to be less useful in differentiating the two isomers. However, the stretching frequencies of some bonds could be quite different due to the different Z- and E-symmetries at the double bond. The C=O and C-F stretching frequencies for both the Z- and E-isomers could be different as the phenyl group on the double bond is nearer to the carbonyl group in the Z-isomer but closer to the fused ring system with the F atom in the E-isomer. The stretching frequencies of some bonds for both the Z- and E-isomers are reported in the literature but they are not labelled. Their results are given in the table below[7].

| Z-isomer | E-isomer | Assumed bond stretches |

|---|---|---|

| 2922 cm-1 | 2924 cm-1 | C-H |

| 1699 cm-1 | 1706 cm-1 | C=O |

| 1486 cm-1 | 1479 cm-1 | C=C |

| 1271 cm-1 | 1285 cm-1 | C-F |

The vibrational normal modes of the two isomer products are calculated using the b3lyp/6-31G(d,p) DFT method DOI:10042/to-3717 , DOI:10042/to-3718 . The important stretching frequencies and their assignments are given in the table below. The predicted wavenumbers are slightly overestimated by 8% for large wavenumbers and this has to be corrected. Wavenumbers for bending and lower frequency modes are usually right and no correction is required. In this case, it is assumed that the stretching frequency of the C-F is not small enough (above 1000 cm-1) and correction is still required.

| Stretching Assignments | Z-isomer (calculated) (cm-1) | Strength of peak | Z-isomer (corrected) (cm-1) | E-isomer (calculated) (cm-1) | Strength of peak | E-isomer (corrected) (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-H (aromatic) | 3175 - 3235 | strong | 2940 - 2996 | 3182 - 3244 | strong | 2946 - 3004 |

| C-H (alkene) | 3134 | medium | 2901 | 3145 | medium | 2912 |

| C-H (methyl) | 3036 - 3092 | strong | 2812 - 2863 | 3034 - 3091 | strong | 2810 - 2862 |

| C=O | 1772 | strong | 1641 | 1801 | strong | 1667 |

| C=C (alkene) | 1677 | strong | 1553 | 1691 | strong | 1566 |

| C=C (aromatic) | 1620 - 1669 | strong | 1500 - 1545 | 1628 - 1671 | strong | 1507 - 1547 |

| C-N | 1314, 1383 & 1411 | medium | 1217, 1280 & 1307 | 1313, 1378 & 1410 | medium | 1216, 1276 & 1305 |

| C-F | 1184 | medium | 1096 | 1240 | medium | 1148 |

Comparing the literature and the calculated/predicted values, it is observed that the predicted values are mostly different than the ones reported in literature. The predicted C-H stretching frequencies are about the same as the one reported in the literature but it is unclear which C-H stretch is referred to in the literature as the C-H stretches could be due to methyl, alkene or aromatic C-H. The predicted C=O and C-F stretching frequencies are smaller than the ones reported in literature for both isomers but the predicted C=C stretching frequencies are larger than the experimental values. However, as the stretching frequencies are not assigned in the literature, the vibrations at 1271 cm-1 (Z-isomer) and 1281 cm-1 (E-isomer) could be due to C-N stretches. If this is the case, then the predicted values are fairly accurate. Overall, the predicted values are not a very good match with the experimental values. This is due to the fact that the predicted vibrational frequencies are based on products in the gaseous state while the ones reported in literature are from products in the liquid form. There could be interactions between the product molecules in gaseous state that are not present in the liquid state, and these interactions affect the vibrations of the molecules and their respective frequency values. This explains the differences in the vibrational frequencies.

Comparing the predicted stretching frequencies of the Z-isomer and that of the E-isomer, it is found that the original prediction that the stretching frequencies of some bonds could be different due to the different Z- and E-symmetries at the double bond is proven correct. The C=O stretching frequency is higher for the E-isomer than the Z-isomer and this is consistent with the trend reported in the literature, although their values are different. A possible reason for the higher stretching frequency of C=O in the E-isomer is the fact that the phenyl group at the alkene is pointing away from the carbonyl group, minimising any possible repulsions with the carbonyl group. This then could allow the carbonyl group to stretch better and hence, a higher stretching frequency for the E-isomer. For the Z-isomer, the phenyl is next to the carbonyl and this may cause the C=O stretching to be weaker as the carbonyl might want to reduce the repulsion between the phenyl group and itself. Another significant difference between the IR spectra of both isomers is the stretching frequency of the C-F bond. The C-F stretching frequency of the E-isomer is larger than that of the Z-isomer. The reason for this is unknown but this is again consistent with the trend given in the literature where the C-F stretching frequency is higher in the E-isomer than in the Z-isomer. Three C-N stretches are reported as there are three types of C-N bonds present in the isomers, with the N atom connected to the C of the methyl group, the carbonyl group and the aromatic ring. The C-N stretching frequencies are about the same in both isomers and this is expected as the environment around the N atom and these bonds are the same in the Z-isomer and the E-isomer. The C-H and C=C stretches in both isomers are predicted to have an almost equal vibrational frequency values with each other and they are not very useful in differentiating both isomers. However, the C=O and C-F stretching frequencies are useful in differentiating the isomers as the E-isomer is shown to have a higher stretching frequency for both the C=O and C-F stretches than the Z-isomer.

13C NMR can also be used to differentiate the 2 isomers. Each C atom in the Z-isomer and the E-isomer (a total of 16 C atoms) are labelled as shown in the diagrams below. The 13C NMR spectra of both isomers are calculated and predicted using the GIAO method after geometry optimization with the mpw1pw91/6-31G(d,p) DFT method DOI:10042/to-3712 , DOI:10042/to-3710 . Every C atom in both isomers is then assigned to its respective chemical shift and its degeneracy is recorded. The 13C NMR data from the literature only gives the chemical shifts and degeneracy of the C atoms without any assignments. Both the literature and predicted chemical shifts and degeneracies are also listed in the tables below[7].

| Carbon Assignment | Z-isomer Chemical Shift (ppm) | Degeneracy | E-isomer Chemical Shift (ppm) | Degeneracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 106.3 | singlet | 106.4 | singlet |

| C2 | 112.7 | singlet | 114.2 | singlet |

| C3 | 155.2 | singlet | 154.3 | singlet |

| C4 | 104.3 | singlet | 107.9 | singlet |

| C5 | 123.1 | singlet | 119.4 | singlet |

| C6 | 134.0 | singlet | 136.8 | singlet |

| C7 | 123.5 | singlet | 124.1 | singlet |

| C8 | 160.2 (δcorr = 166.0) | singlet | 162.0 (δcorr = 167.7) | singlet |

| C9 | 25.6 | singlet | 26.0 | singlet |

| C10 | 139.7 | singlet | 139.4 | singlet |

| C11 | 130.4 | singlet | 131.7 | singlet |

| C12 | 133.4 | singlet | 125.0 | singlet |

| C13 | 124.6 | singlet | 124.9 | singlet |

| C14 | 129.0 | singlet | 127.3 | singlet |

| C15 | 125.5 | singlet | 125.0 | singlet |

| C16 | 124.6 | singlet | 125.7 | singlet |

| Z-isomer Chemical Shift (ppm) | Degeneracy | E-isomer Chemical Shift (ppm) | Degeneracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26.0 | singlet | 26.3 | singlet |

| 106.5 | singlet | 108.4 | singlet |

| 106.8 | singlet | 110.2 | singlet |

| 108.2 | singlet | 110.6 | singlet |

| 108.3 | singlet | 115.9 | doublet |

| 114.9 | doublet | 122.0 | singlet |

| 125.7 | singlet | 126.9 | singlet |

| 128.3 | singlet | 129.2 | singlet |

| 130.9 | singlet | 129.9 | singlet |

| 132.2 | singlet | 134.4 | singlet |

| 133.4 | singlet | 138.6 | singlet |

| 138.3 | singlet | 140.3 | singlet |

| 159.0 | doublet | 158.4 | doublet |

| 165.9 | singlet | 168.2 | singlet |

Comparing the degeneracy of the peaks in the 13C NMR, it is found that the degeneracy of the carbon peak is always singlet for the predicted peaks. This is because the chemical shifts of the carbon peaks are approximated on a static molecule in the computational method. On the other hand, the experimental 13C NMR spectra have peaks that show degeneracy such as singlets and doublets as the spectrum is taken on a free-rotating, moving molecule. The carbonyl C atom (C8) has the highest chemical shift since it is bonded directly to an electronegative O atom. This is observed in both Z- and E-isomers, and this means that the 165.9 ppm and 168.2 ppm chemical shifts reported in the literature are due to the carbonyl C. The second largest chemical shift is due to the C atom that is directly bonded to the electronegative F atom (C3) as this C atom is not only in an aromatic ring but also connected to an electronegative atom. This means that the chemical shifts at 159.0 and 158.4 ppm in the literature are due to this type of C atom. These peaks are also observed to be a doublet. This is caused by the coupling between the C atom and the F atom which is a spin 1/2 nuclei (2nI + 1 = 2, where n=1 and I=1/2). The smallest chemical shift is due to the C atom of the methyl group (C9) as it is a primary carbon. The experimental 13C NMR spectra also show 2 peaks that have very small chemical shift (26.0 and 26.3 ppm) and this must be the peak due to the methyl C atom.

It is harder to assign C atoms to the other chemical shifts given in the literature as they are not very obvious. However, from the computational method, it is expected that the chemical shifts from 106.5 - 114.9 ppm in the Z-isomer and 108.4 - 122.0 ppm in the E-isomer are most likely due to the C atoms on the fluoro-benzene group. The chemical shifts from 125.7 - 133.4 ppm in the Z-isomer and 126.9 - 134.4 ppm in the E-isomer are most likely due to the C atoms on the phenyl group attached to the alkene bond. An important thing to note from the 13C NMR data given in the literature is that there is only 14 chemical shifts reported instead of the expected 16 C atoms. This can be explained by considering equivalent C atoms in both isomers. C12 and C16, and C13 and C15 can be considered as equivalent carbons in both the Z-isomer and E-isomer, hence, instead of 4 peaks, only 2 peaks are observed (1 for C12 and C16 and another 1 for C13 and C15).

Comparing the predicted 13C NMR spectra of the Z-isomer and the E-isomer, it is found that there is a considerable difference in the chemical shifts of the carbonyl carbon, C8. The E-isomer is found to have a higher chemical shift than the Z-isomer, and this is consistent with the literature. Also, the chemical shifts of the two C atoms next to the C atom bonded to F (C2 and C4) are also significantly different for the two isomers. The E-isomer has higher chemical shifts for these C atoms while the Z-isomer has slightly lower values. These can be used to differentiate the two isomers if we are able to assign them correctly, which is not too difficult to do as we know that C1, C2 and C4 have the next lowest chemical shifts after C9. The chemical shifts for C5, C6, C12 and C14 are quite different for both the Z- and E-isomers but they are not useful in differentiating the two isomers as it is very difficult to assign these four peaks and their chemical shifts accurately. Overall, the 13C NMR spectra give a limited way of differentiating the Z-isomer and the E-isomer. However, the predicted 13C NMR spectra give a reasonable well match with the experimental spectra for both isomers, suggesting the usefulness of the computational method in checking and confirming the assigned carbon chemical shifts from the experimental spectra.

A more useful way of differentiating the two isomers is to use the Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) spectroscopy. This is the measure of the signal enhancement of certain H atoms when double irradiation occurs. The NOE occurs through space, and not through bonds, unlike the J-coupling. Therefore, only atoms that are in close proximity of each other show the NOE. For the Z-isomer, if the second irradiation is performed on the alkene H atom (bonded to C10), the intensity of the peak due to the H atom connected to C4 or C12 will be increased in the 1H NMR spectrum. This is because these two H atoms are spatially quite close to the alkene H atom due to the almost planar structure of the Z-isomer and the alkene H atom gives a NOE to them. On the other hand, for the E-isomer, the second irradiation on the alkene H atom (bonded to C10) will not give a signal enhancement on the peaks due to the H atom connected to C4 or C12 as these H atoms are not near the alkene H atom. The only peak that might show a signal enhancement is the peak due to the H atom bonded to C16. However, the signal enhancement may be small as the phenyl group, to which that particular H atom is attached to, is twisted at an angle, causing the 2 H atoms to be not planar to each other. As both the Z-isomer and the E-isomer show different signal enhancements in the 1H NMR spectrum due to NOE, the NOE spectroscopy method is a very good way to differentiate the two isomer products.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838: DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ S. Leleu, C.; Papamicael, F. Marsais, G. Dupas, V.; Levacher, Vincent. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928: DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 S. W. Elmore, L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 32, 319: DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 W. F. Maier, P. V. R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1981, 103, 1891-1900: DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447: DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ B. Halton, S. G. G. Russell, J. Org. Chem, 1991, 56, 5553 - 5556: DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 T. Jiang, R. Tang, X. Zhang, X. Li, J. Li, J. Org. Chem, 2009, 74, 8834 - 8837: DOI:10.1021/jo901963g