Rep:Mod:kl1111syn

Part 1: Conformational Analysis using Molecular Mechanics

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

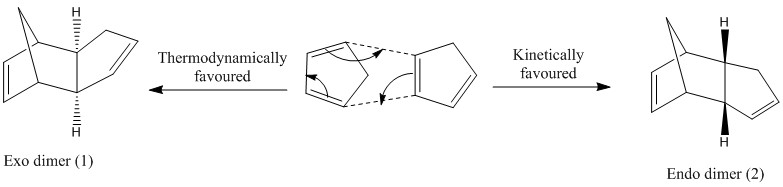

Cyclopentadiene may undergo a Diels-Alder reaction in which a [Π4s + Π2s] cycloaddition occurs, to form its dimeric form, dicyclopentadiene. The total number of electrons in the reaction equals 6, which follows the 4n+2 rule and thus the thermal reaction should proceed suprafacially via a Huckel transition state, to form either the exo or the endo form of dicyclopentadiene.

The dimerisation is stereospecific and thus dependent on the position of the dienophile relative to the diene. In the case that it is directed towards the diene, the kinetically favoured endo form is produced, and if the dienophile is directed away from the diene, the thermodynamically favoured exo form is produced.

It has been reported in literature [1] that the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene may achieve equilibrium when severe reaction conditions are used. In most cases, the reaction is therefore kinetically controlled and so the endo product is formed faster despite it being less stable than the exo product due to secondary orbital overlap effects which help to stabilise it.

The endo and exo structures were both analysed in Avagadro and optimised using the MMFF94s force field to calculate their relative energies. The contributions from bond stretching, angle bending, torsion, Van der Waals and electrostatic energy can all be seen using this method and these parameters represent a deviation from normality for a particular function.

| Exo Dimer (1) | Endo Dimer (2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kcalmol-1) | ||||||

| Bond Stretching Energy | 3.54314 | 3.46124 | ||||

| Bond Angle Bending Energy | 30.77255 | 33.23837 | ||||

| Torsional Energy | -2.73069 | -2.93825 | ||||

| Van der Waals Energy | 12.80140 | 12.33163 | ||||

| Electrostatic Energy | 13.01367 | 14.16211 | ||||

| Total Energy | 55.37342 | 58.19961 |

As seen above, the exo product is the thermodynamically more stable product, being 2.82 kcalmol-1 lower in energy when compared to the endo product. The parameters above are very similar for both products, aside from the bond bending energy which differs by 2.47 kcalmol-1. The difference in stability may therefore be attributed to the difference in bond angle bending energy.

| Exo Dimer (1) | Endo Dimer (2) |

|

|

Since both molecules differ only by the position of the 6-membered ring relative to the rest of the molecule, the bond angle bending energy can be defined as being the angle between the two rings. The carbon linking the two rings together is sp3 hybridised and a bond angle of 109.5° is expected. However, in both cases, it can be seen that the bond angle for carbon has deviated significantly from ideality, with the endo dimer being more so. This can explain why the endo dimer is thermodynamically less stable compared to the exo dimer.

The dimerisation of cyclopentadiene leads to the formation of only the endo dimer [1]. The endo dimer has been shown to be thermodynamically less stable than the exo dimer and thus it must be the case that the reaction is under kinetic control. The endo pathway must therefore have a transition state which is more stable (lower activation energy) than that of the exo pathway due to secondary orbital overlap and so the endo product is formed faster.

Hydrogenation of endo-dicyclopentadiene

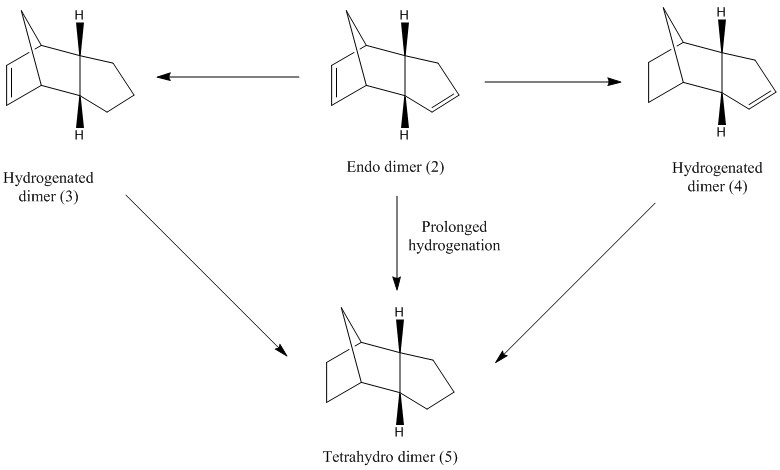

Hydrogenation of dimer 2 leads to either the dihydro dimer 3 or 4. Only after prolonged hydrogenation is complete hydrogenation of the molecule (5) achieved. This means that the hydrogenation does not occur simultaneously at both double bonds, and either 3 or 4 may be formed faster than the other depending on which is thermodynamically more stable. To determine which dihydro derivative is formed first, the relative energies of both molecules were analysed using the method used previously. (Avagadro, MMFF94s)

| Hydrogenated Dimer 3 | Hydrogenated Dimer 4 | |||||

| (kcal/mol) | ||||||

| Bond Stretching Energy | 3.31235 | 2.82311 | ||||

| Bond Angle Bending Energy | 32.36780 | 24.68533 | ||||

| Torsion Energy | -1.81541 | -0.37841 | ||||

| Van der Waals Energy | 13.78635 | 10.68093 | ||||

| Electrostatic Energy | 3.03027 | 2.99926 | ||||

| Total Energy | 48.57642 | 39.15333 |

Molecule 4 has the lower energy of the two and is therefore thermodynamically more stable. The parameters for both molecules are very similar but it is clear that both the bond angle bending energy and Van der Waal's energy differ significantly by 7.68 and 3.11 kcalmol-1 respectively and this will be examined further to explain why molecule 4 is more stable.

| Molecule 3 | Molecule 4 |

|

|

| 93.3° | 93.7° |

|

|

| 107.5° | 102.9° |

Norborane and Norborene molecules are highly strained due to the presence of a methylene group on the 6-membered ring which is restricted to a bond angle of approximately 93.5° for both molecules instead of the ideal 109.5° for sp3 hybridised structures. However, molecule 3 is less stable than 4 and this is due to the presence of the double bond within the ring. In molecule 3, the ideal bond angle for this sp2 hybridised carbon should be 120° and the ideal bond angle for molecule 4 is 109.5° for the sp3 hybridised carbon. If the actual bond angles are compared to their ideal values, it is clear that molecule 3 has deviated more from its ideal bond angle and thus is more strained and less stable compared to molecule 4.

Van der Waals energy may also contribute to one of the molecules being more stable than the other, and is defined as the interaction energy between two non-bonded atoms within close proximity. For a C-C bond, the Van der Waal radius is 3.40Å. If the calculated bond length between two carbon atoms is smaller than this value, the Van der Waals interaction energy will increase as repulsion increases.

| Molecule 3 | Molecule 4 | |

| 1 |

|

|

Due to the similarity of the two molecules, only the important bond lengths were measured. The distance between the methylene carbon and the alkene/alkane carbon was measured. The distance is smaller for molecule 3 and the double bond seems to account for increased repulsion. However, Van der Waals interaction only contributes a little to the overall energy for both molecules and it is the bond angle bending interaction that is significant in explaining why molecule 4 is thermodynamically more stable than 3.

The energy difference between endo-dicyclopentadiene (molecule 2) and molecule 3 is 9.62 kcalmol-1 and is 19.05 kcalmol-1 between molecule 2 and 4. Since the stabilization energy is greater for molecule 4, this is the product that will form faster in the case that the reaction is thermodynamically controlled. According to literature, this has been proven correct and product 4 is the predominant intermediate due to steric hindrance effects [2]

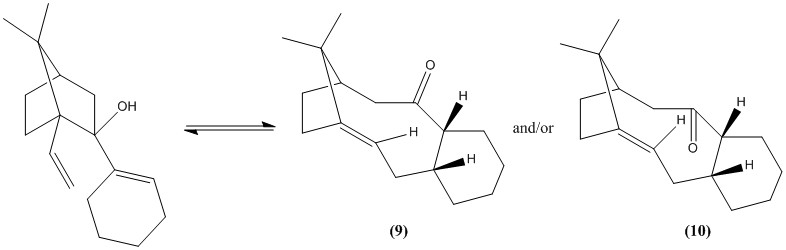

In the synthesis of taxol, the intermediates formed show atropisomerism due to the presence of two rings locking the positions of the substituents in place and are thus isolatable. The two intermediates formed are stereoisomers and differ only in the position of the carbonyl group relative to the plane of the ring. In molecule 9, the carbonyl group is above the plane of the ring, syn to the methylene bridge whereas the carbonyl group is below the plane or anti to the methylene bridge in molecule 10.

The reaction is reversible and when left standing, the thermodynamically more stable isomer will predominate. To determine which stereoisomer will predominate, the energies of both molecule 9 and 10 were calculated using Avagadro with the MMFF94s force field. Due to the presence of the cyclohexane ring, it may alter its conformation to adopt structures of lower energies, controlling the conformation of the rest of the molecule. Out of a total of 7 conformations that may exist, only 4 are isolatable and these are the chair and twist boats conformations, both of which are made of 2 diastereomers. The chair conformation is expected to give the lowest energy due to it having the least torsional strain.

| Chair 1 | Chair 2 | Twist Boat 1 | Twist Boat 2 | |||||||||

| JSmol image | ||||||||||||

| Energy (kcalmol-1) | 70.53937 | 82.69993 | 88.51589 | 76.28195 |

| Chair 1 | Chair 2 | Twist Boat 1 | Twist Boat 2 | |||||||||

| JSmol image | ||||||||||||

| Energy (kcalmol-1) | 60.55165 | 74.73915 | 66.28484 | 68.87551 |

As expected, the chair conformation is the lowest energy conformation for both isomers. If both of these chair conformations are compared side by side, it can be seen that atropisomer 10 is the more stable molecule, being lower than the other isomer by 9.99 kcalmol-1.

| Atropisomer 9 (Chair 1) | Atropisomer 10 (Chair 1) | |||||

| (kcalmol-1) | ||||||

| Bond Stretching Energy | 7.67308 | 7.59505 | ||||

| Bond Angle Bending Energy | 28.29236 | 18.81573 | ||||

| Torsional Energy | 0.24247 | 0.25211 | ||||

| Van der Waals Energy | 33.13329 | 33.24028 | ||||

| Electrostatic Energy | 0.30313 | -0.05351 | ||||

| Total Energy | 70.53937 | 60.55165 |

Again, the energy parameters are very similar for both aside from the bond angle bending energy. Since the bond angle bending energy is greater for atropisomer 9, the bond angles must deviate more significantly than those for isomer 10.

| Atropisomer 9 | Atropisomer 10 |

|

|

| 95.5° | 96.84° |

|

|

| 123.04° | 118.25° |

The CCC bond angles observed above for tetrahedral structures have significantly deviated from the ideal 109.5°, with atropisomer 9 being deviated more so than 10. This helps to explain why 10 is the more stable isomer and should also be the isomer that is formed first and predominately in the synthesis of taxol when under thermodynamic control.

In 1924, Bredt predicted that double bonds avoid being located at ring junctions and would be very reactive. However, isomer 10 has been shown to functionalise very slowly despite having a bridgehead olefin. It was not until 1970 when Wiseman realised that bridghead olefins were isolatable when contained within a trans-cycloalkane system with more than 8 carbon atoms. [3] Isomer 10 is relatively stable due to it being a "hyperstable" olefin, compounds which are less strained than its parent hydrocarbon and display decreased reactivity due to the double bond being located at the bridgehead.[4]

| Isomer 10 | Isomer 10b | |||||

| kcalmol-1 | ||||||

| Bond Stretching Energy | 7.59505 | 5.70562 | ||||

| Bond Angle Bending Energy | 18.81573 | 25.02510 | ||||

| Torsional Energy | 0.25211 | 7.43483 | ||||

| Van der Waals Energy | 33.24028 | 28.49927 | ||||

| Electrostatic Energy | -0.05351 | 0.00000 | ||||

| Total Energy | 60.55165 | 66.96928 |

Both isomer 10 and its parent hydrocarbon were compared and the energy of 10 has been shown to be lower than its saturated counterpart. Analysis of the above parameters show that bond angle bending energy and torsional energy contribute mainly to the overall stability of the molecule, however it has been stated in literature that torsional energy contributes little to hyperstability and thus only bond angle bending energies will be analysed.[5]

| Isomer 10 | Isomer 10b |

|

|

| 123.69° | 125.89° |

Molecule 10 is sp2 hybridised and the bond angle observed above is fairly similar to this value, only deviating from ideality by 3.69°. Molecule 10b is sp3 hybridised however, and so the bond angle observed deviates from ideality by a greater amount, equating to 16.39°. Since molecule 10 is less strained, it is more stable compared to molecule 10b, and explains why it reacts slowly.

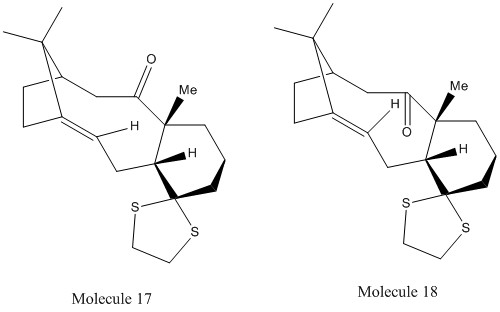

Molecules 17 and 18 are derivatives of molecules 9 and 10 respectively. The cyclohexane ring adopts the most energetically favourable conformation and adjusts the conformation of the rest of the molecule to match it. This means that the cyclohexane rings in both 17 and 18 will adopt a chair conformation to be thermodynamically stable. Both molecules were analysed using Avagadro and the MMFF94s force field and their relative energies compared.

| 17[6] | 18[7] | |||||

| kcalmol-1 | ||||||

| Bond Stretching Energy | 15.71455 | 15.00664 | ||||

| Bond Angle Bending Energy | 32.11149 | 30.90258 | ||||

| Torsional Energy | 11.35015 | 9.67983 | ||||

| Van der Waals Energy | 51.43471 | 49.38363 | ||||

| Electrostatic Energy | -7.59874 | -6.03955 | ||||

| Total Energy | 104.29660 | 100.48739 | ||||

| Gibbs free energy (au) | -1651.463258 | -1651.459443 |

Molecule 18 has been found to be marginally more stable than 17 which is to be expected if molecule 10 is more stable than 9. In addition, the carbonyl group in molecule 18 are anti to the two methyl groups, leading to less steric repulsion. Their Gibbs free energies were also analysed and it was found that molecule 18 had a lower Gibbs free energy value, equating to it being thermodyamically more stable than 17.

Molecule 18 has been chosen for its spectroscopic data to be analysed. To simulate the NMR spectra, the minimum energy structure was found, with the cyclohexane ring in a chair conformation. This structure was then optimised using the MMFF94s force field and the geometry calculated at the density functional level (DFT) in Avagadro. After the calculations were run, a spectrum was obtained and TMS B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p) GIAO was used as a reference.

Molecule 18 1H NMR Spectrum

|

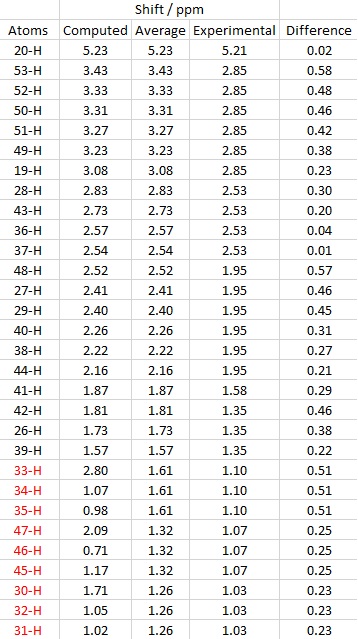

Computed[8] | Experimental[9] | ||

| δ (ppm) | Integration | δ (ppm) | Integration | |

| 5.23 | s, 1H | 5.21 | m, 1H | |

| 3.43 | s, 1H | 3.00-2.70 | m, 6H | |

| 3.28 | s, 4H | |||

| 3.08 | s, 1H | |||

| 2.81 | s, 1H | 2.70-2.35 | m, 4H | |

| 2.73 | s, 1H | |||

| 2.54 | s, 3H | |||

| 2.41 | s, 2H | 2.20-1.70 | m, 6H | |

| 2.24 | s, 2H | |||

| 2.16 | s, 1H | |||

| 1.87 | s, 1H | 1.58 | t, 1H | |

| 1.81 | s, 1H | 1.50-1.20 | m, 3H | |

| 1.72 | s, 1H | |||

| 1.57 | s, 1H | |||

| 1.62+ | s, 3H | 1.10 | s, 3H | |

| 1.32+ | s, 3H | 1.07 | s, 3H | |

| 1.26+ | s, 3H | 1.03 | s, 3H | |

+ denotes the fact that Gaussian cannot compute for rapid bond rotation and thus protons that should be in the same environment are not recognised. For this reason, the 9 methyl protons present in molecule 18 are given as individual peaks with different chemical shifts. The chemical shift of the methyl protons was taken as an average of their individual values.

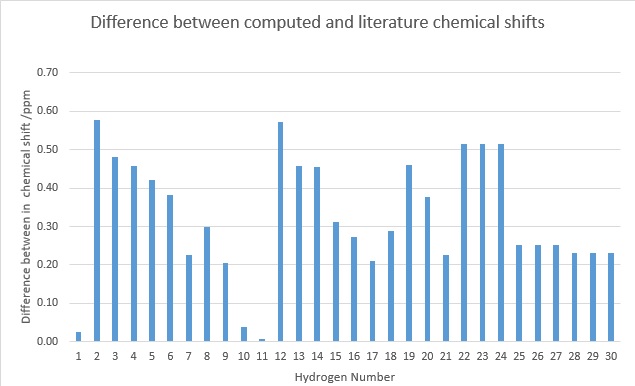

The table above indicates the hydrogen number and their respective chemical shifts. The shifts coloured red are methyl proton shifts and have been averaged. The difference between the computed and experimental chemical shifts were then calculated, and a table displaying the data created. As seen on the table of the right hand side, there is quite a large deviation in chemical shifts, with the largest deviation being nearly 0.60 ppm. This is quite significant as proton NMR typically displays a small range between 0-14 ppm and a small change in chemical shift would appear as a different functional group.

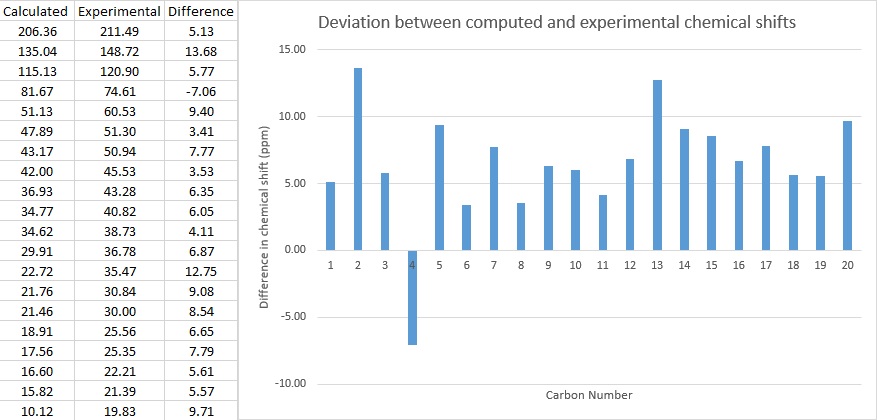

Molecule 18 13C NMR Spectrum

|

Computed[10] δ (ppm) | Experimental[9] δ (ppm) |

| 206.36 | 211.49 | |

| 135.04 | 148.72 | |

| 115.13 | 120.90 | |

| 81.67 | 74.61 | |

| 51.13 | 60.53 | |

| 47.89 | 51.30 | |

| 43.17 | 50.93 | |

| 42.00 | 45.53 | |

| 36.93 | 43.28 | |

| 34.77 | 40.82 | |

| 34.62 | 38.73 | |

| 29.91 | 36.78 | |

| 22.72 | 35.47 | |

| 21.76 | 30.84 | |

| 21.46 | 30.00 | |

| 18.91 | 25.56 | |

| 17.56 | 25.35 | |

| 16.60 | 22.21 | |

| 15.82 | 21.39 | |

| 10.12 | 19.83 |

The same reference and basis set was used in the carbon NMR simulation.

As shown above, the difference in chemical shift between computed and literature values were calculated and a table displaying the deviation across all atoms were displayed. There is an average deviation of 6.54 ppm. Since the NMR range for 13C NMR is between 0-300 ppm, the deviation is not significant and the computed data is quite a good match with experimental data.

For both NMR simulations, the input file was modified to account for the use of chloroform as a solvent and the basis set was set to B3LYP/6-31 g(d,p). In viewing the NMR, TMS was used as a reference and the B3LYP-G(2d,p) GIAO basis set was used as it was the closest to what was used in the input file. However, the solvent used in literature[9] was deuterated benzene and this may account for the significant deviation seen in the computed NMR simulation values.

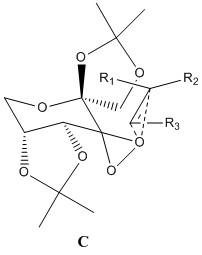

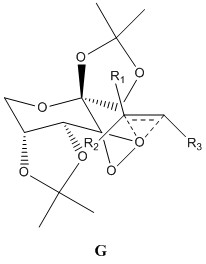

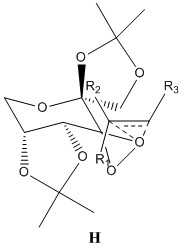

Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

One of the third year synthesis lab experiments (1S: Asymmetric Epoxidation of Alkenes) consisted of preparing two catalysts; the salen based-manganese containing Jacobsen catalyst and the fructose derived Shi catalyst. The enantioselectivity of the catalysts were tested by carrying out an aymmetric epoxidation on two alkenes: trans-stilbene and 1,2-dihydronapthalene. The structures of both catalysts and alkenes are given below.

| Shi Catalyst | Jacobsen Catalyst | 1,2-dihydronapthalene | trans-Stilbene |

|

|

|

|

Catalyst Crystal Structures

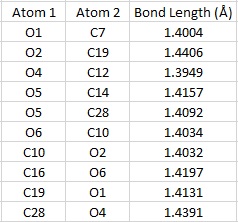

The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) was searched for the crystal structures of the pre-catalysts 21 and 23. These molecules then had their bond distances and angles measured using the Mercury program.

Shi Catalyst

The anomeric effect was originally used to describe the preference of heteroatomic substituents adjacent to a heteroatom to occupy the axial position within a cyclohexane ring over the equitorial position, despite it being sterically less favourable. The effect has now been generalised and can be applied to ring systems with CYCX substructures where Y is an electronegative element and X is a heteroatom with a lone pair. In this case, a hyperconjugation interaction occurs between the the lone pair on X and the antibonding orbital of the adjacent CY bond. The interaction causes the CY bond to lengthen and weaken whilst the XC bond is shortened.[11]

The Shi catalyst contains anomeric centres and the crystal structure for 21 was analysed to determine whether any anomeric interactions had taken place.

|

|

There are three anomeric centers present in molecule 21, these are located at carbon numbers 10, 19 and 28. The effect is most prevalent at 19 and 28. There are 2 dioxolane rings present within the molecule and by observing the ring on the left side of the molecule, one can see that the C28-O4 bond is longer than that of the C12-O4 or C14-O5 bond. The same can be said for the ring on the right hand side of the molecule. The anomeric effect is clearly taking place within the ring, causing the bond lengths to differ. The lone pair on O5 is aligned anti-periplanar to the C28-O4 bond, and thus can be donated to its antibonding orbital, causing the C28-O5 bond to lengthen dramatically. The lone pair on O1 is also be donated to the antibonding orbital of the C19-O2 bond, causing it to lengthen.

The central cyclohexane ring is in the stable chair conformation. There is an anomeric center present at C10, and both oxygens bonded to this carbon are aligned perfectly to the other C-O bond, and a potential anomeric effect may take place. Both C10-O6 and C10-O2 bond lengths are the same, measuring at 1.403Å and this may indicate equivalent anomeric interactions taking place. However, these bonds are shorter than those seen in C19-O2 and C28-O4, and may be caused by C10 being close to the electron withdrawing carbonyl group.

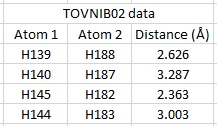

Jacobsen's Catalyst

Two crystal structures were found for the Jacobsen's catalyst; TOVNIB01 and TOVNIB02. The distances between the hydrogens of the two adjacent t-butyl groups within the complex were measured for the TOVNIB02 structure.

|

|

|

The Mn complex was found to be non planar, having a bond angle of 154 degrees. The distance between the hydrogens of the two butyl groups was found to be greater than the sum of the Van der Waals radii for two hydrogen atoms (2.40Å). These distances signify some attractive forces present between the butyl groups and this induces them to come closer together and distort the planarity of the molecule. As the molecule is distorted, the face with the Mn-Cl bond is sterically less hindered and thus favoured over the the other face and this also allows alkenes to avoid approaching the molecule from over the bulky butyl groups. This supports work by Jacobsen and Katsuki[12][13] and can be seen on the right hand side of the table above.

Assigning the absolute configuration of the product

When conducting experiment 1S, the asymmetric epoxidation of trans-stilbene and 1,2-dihydronapthalene were conducted using both the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts. The epoxidation of trans-stilbene should produce a mixture of (R,R) and (S,S)-stilbene oxides whilst the epoxidation of 1,2-dihydronapthalene should produce (1S,2R) and (1R,2S)-dihydronapthalene oxides. The formation of one enantiomer over another depends on the selectivity of the catalyst used and the reasons as to why will be explained.

|

|

The 1H and 13C NMR spectra for Trans-stilbene oxide and 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide was miinimised using the MMFF94s force field and then optimised using the B3LYP/6-31G (d,p) basis set. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and optical rotation values were calculated and compared to literature data to deduce the identity of the enantiomer modelled.

Stilbene Oxide

1H NMR of Stilbene Oxide

|

Computed[14] | Experimental[15] | ||

| δ (ppm) | Integration | δ (ppm) | Integration | |

| 7.71 | s, 2H | 7.52–7.42 | m, 10H | |

| 7.62 | s, 8H | |||

| 3.67 | s, 2H | 3.98 | s, 2H | |

| ||||

13C NMR of Stilbene Oxide

|

Computed δ (ppm)[14] | Experimental δ (ppm)[15] |

| 124.38 | 137.70 | |

| 114.52 | 129.10 | |

| 113.81 | 128.80 | |

| 113.51 | 128.80 | |

| 113.37 | 126.10 | |

| 108.56 | 126.10 | |

| 56.71 | 63.30 | |

| ||

The computed NMR values for stilbene oxide look similar to those obtained in literature[15]. However, the largest deviation in the 1H NMR is approximately 0.3 ppm and for 13C NMR it is about 17ppm. These deviations are quite small and large deviations may be due to the conformation of the molecule or the computational method used.

Calculated Chirooptical Properties of trans-Stilbene Oxide

The optical rotation of trans-stilbene oxide was computed using the B3LYP method, 6-31++G(2d,p) basis set. This method was calculated at 589nm and the data modeled using chloroform as a solvent. The computed values for both the R,R and S,S enantiomers have been tabulated below for comparison with literature values.

| (R,R) | (S,S) | |

| Computed | +298.12°[16] | -298.11°[17] |

| Experimental | +250.80°[18] | -249.00°[19] |

The computed optical rotations for trans-stilbene oxide are similar to the values obtained in literature. This indicates that the computational methods used were accurate.

Dihydroapthalane Oxide

1H NMR spectrum of 1,2-dihydronapthalene Oxide

|

Computed[20] | Experimental[15] | ||

| Δδ (ppm) | Integration | Δδ (ppm) | Integration | |

| 7.63 | s, 1H | 7.45 | d, 1H | |

| 7.52 | s, 2H | 7.35-7.20 | m, 2H | |

| 7.33 | s, 1H | 7.15 | d, 1H | |

| 3.72 | s, 2H | 3.90 | d, 1H | |

| 3.77 | t, 1H | |||

| 3.02 | s, 1H | 2.85-2.80 | m, 1H | |

| 2.40 | s, 1H | 2.60-2.55 | m, 1H | |

| 2.35 | s, 1H | 2.50-2.40 | m, 1H | |

| 1.70 | s, 1H | 1.80-1.75 | m, 1H | |

| ||||

13C NMR spectrum of dihydronapthalene oxide

|

Computed Δδ (ppm)[20] | Experimental Δδ (ppm)[21] |

| 124.14 | 137.10 | |

| 120.68 | 132.90 | |

| 115.85 | 129.90 | |

| 114.13 | 129.80 | |

| 113.72 | 128.80 | |

| 111.74 | 126.50 | |

| 46.73 | 55.50 | |

| 45.12 | 53.20 | |

| 18.33 | 24.80 | |

| 15.24 | 22.20 | |

| ||

The computed 1H and 13C NMR spectra agree closely with those found experimentally. The largest deviation found in the 1H NMR is 0.27ppm and for 13C, it is nearly 16ppm. These deviations are fairly small and most likely arise from the computational method used or from differences in the conformation of the molecule.

Calculated Chiroptical Properties of dihydronapthalene oxide

The optical rotation of dihydronapthalene oxide was computed from the previous output file obtained from the NMR calculation using the B3LYP method, 6-31++G(2d,p) basis set. This method was calculated at 589nm and the data modeled using chloroform as a solvent. The computed values for both the 1R,2S and 1S,2R enantiomers have been tabulated below for comparison with literature values.

| (1R,2S) | (1S,2R) | |

| Computed | +155.82°[22] | -155.82°[23] |

| Experimental | +133.0°[24] | -133.0°[24] |

The computed optical values for dihydronapthalene oxide are similar to the values obtained experimentally. This indicates that the computational methods used are accurate.

Using the calculated properties of the transition state for the reaction

The selectivity of both the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts on different substrates can be determined by analysis of the transition state structures. These energies were corrected for entropy and zero-point energies and also the presence of water as a solvent. The lowest energy transition structures are the most stable and the difference (Gibbs free energy) can be related to the equilibrium constant by the formula ΔG=-RTlnK and then the enantiomeric excess (e.e) can be calculated from the equation: e.e=(K-1)/(K+1).[25]

Transition State for the Shi Epoxidation of trans-Stilbene

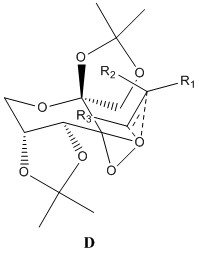

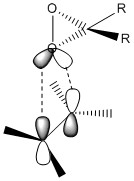

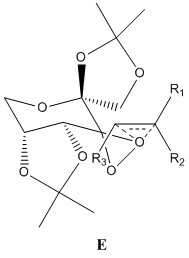

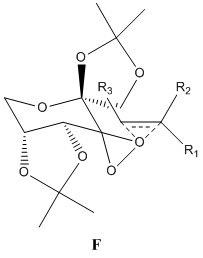

For a fixed chirality of the Shi catalyst, there are a possible 8 transition states.[26] The many varieties arise from whether the Re or the Si form of the alkene is reacting, which of the 2 diasteromeric dioxirane oxygens take part in the reaction and the position of the phenyl group relative to the fructose (exo or endo). The 8 transition states can be split into 2 groups, spiro and planar. It has been reported that the spiro state is favoured over the planar state in the epoxidation of alkenes with dioxirane compounds due to the interaction of the dioxirane oxygen lone pair with the antibonding orbital of the alkene which is only possible in the spiro state.[27] The orbital interactions between the alkene and dioxirane oxygen are shown below. Also shown in the table are the 8 possible transition states.

| State | Orbital Interactions | Transition State Structure | |||

| Spiro |

|

|

|

|

|

| Planar |

|

|

|

|

|

Within the 8 transition states, only spiro A and planar E are favourable, with the rest consisting of unfavourable steric interactions between the dioxirane ring and the alkene substituents. Both spiro A and planar E form epoxides of opposite configurations[26] and it has been found that the Shi catalyst is most effective in epoxidizing trans or trisubstituted alkenes,[28] via the spiro A transition state. 8 transition state structures were provided, corresponding to 4 R,R and S,S epoxides. By analyzing which is the lowest energy structure, it is possible to determine which enantiomer has reacted via the spiro A pathway and will be formed in excess. The next lowest energy structure can be assigned as reacting through the planar E pathway. Since trans-stilbene is a trans-alkene, its transition state structures were analysed and the results given below.

| (R,R) Transition State | (S,S) Transition State | ||||

| Free Energy (au) | -1534.700037 | -1534.693818 |

By observing the above transition states, it can be seen that both are orientated very similarly in a way to minimize steric interactions between the bulky phenyl rings of the tran-stilbene and the dioxolane groups on the catalyst. The R,R transition state can be seen to be lower in energy compared to the S,S enantiomer by 0.006219 au, and thus it is the R,R enantiomer which will be formed in excess. For the Shi catalysed epoxidation of trans-stilbene, the value of k can be calculated to be 728.01 and thus the enantiomeric excess can be calculated to be 99.7%, which is very similar to the value of 98% obtained in literature.[26]

Transition state for the Jacobsen epoxidation of 1,2-dihydronapthalene

There are 4 possible transition state structures for the Jacobsen epoxidation, and these depend on the position of the alkene relative to the catalyst and whether the (R,S) or the (S,R) enantiomer is formed. There are many theories that attempt to explain the high selectivity obtained with Jacobsen's catalyst, all of which use a "side on" approach from the alkene to the complex to allow favourable orbital overlap.[12] There are four pathways shown in the image above and Jacobsen originally proposed that the alkene appraoched the catalyst from over the diamine bridge via pathway A, since it avoids steric clash with the bulky t-butyl groups. However, this hypothesis was rejected by Katsuki who claimed that the pathway A could not explain the high enantiomeric excesses obtained with cis-alkenes and instead proposed pathway B in which the alkene apporached over the Mn-N bond via pathway C.[12] This argument could explain the degree of asymmetric induction obtained using a combination of steric interactions and π,π-repulsive interactions. Since then, Katsuki have modified their argument, as there is evidence to show that the Mn-catalyst is not planar but "stepped" and this leads to pathway C being favoured. In this conformation, the bulky t-butyl substituents do not actually prevent the alkene from approaching via this pathway. H. Jacobsen and Cavallo have conducted computational studies which support this finding, and found that the t-butyl groups are neccessary for blocking pathway D.[12] This may explain why enantiomeric excesses obtained for trans-alkenes are poor. Since Jacobsen's catalyst has proven to provide high enantiomeric exccesses for cis-alkenes, an analysis of 1,2-dinapthalene's transition state was carried out.

| (R,S) Transition State | (S,R) Transition State | ||||

| Free Energy (au) | -3421.359499 | -3421.369033 |

As stated previously, the interactions between the 2 t-butyl groups are bulky and the plane of the complex will distort away from planarity in order to minimize steric interactions. This means that alkenes are more likely to apporoach from the top face of the catalyst, on the side with the Mn-Cl or Mn=O bond. This is supported in the above transition states where the alkenes are coming towards the Mn=O face of the catalyst. The S,R transition state is lower in energy compared to its diasteroisomer by 0.009534 au and hence it is enantiomer which will be formed in excess. Using the same method as described in the calculating the e.e for trans-stilbene oxide, the k value for the Jacobsen epoxidation of 1,2-dihydronapthalene can be found to be 24422.1503 and thus the e.e can be calculated to be 99.99% which is slightly higher than the value of 86% obtained in literature. [29]

Investigating the non-covalent interactions (NCI)and the Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

During a chemical reaction, there is a change in electron density. Thus, by examining the electron density of a system, it is possible to get an insight into the electron structure and the reactivty of a molecule. The two methods used to do this were QTAIM and NCI.

NCI analyses the electron density gradient of a system. It uses a colour sysyem to indicate whether an non-covalent interaction is likely to occur, with blue being most likely and red being most unlikely. Complementary to this is the QTAIM method which relates topological properties of the electron density to the structural properties of the system.

The lowest energy transition state for the Shi epoxidation of trans-stilbene was subjected to these two methods.

| NCI | QTAIM |

|

|

Suggesting new candidates for investigations

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 M. A. Fox, R. Cardona and N. J. Kiwiet, "Steric effects vs. secondary orbital overlap in Diels-Alder reactions. MNDO and AM1 studies", J. Org. Chem., 1987, 52, 1469–1474. DOI:10.1021/jo00384a016

- ↑ G. Liu, Z. Mi, L. Wang and X. Zhang, "Kinetics of Dicyclopentadiene Hydrogenation over Pd/Al2O3Catalyst", Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2005, 44, 3846–3851.DOI:10.1021/ie0487437

- ↑ J. R. Wiseman and W. A. Pletcher, "Bredt's rule. III. Synthesis and chemistry of bicyclo[3.3.1]non-1-ene", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1969, 92, 956–962. DOI:10.1021/ja00707a035

- ↑ W. F. Maler and P. von R. Schleyer, "Evaluation and prediction of the stability of bridgehead olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891–1900.DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ J. Kim, "The Molecular Mechanics Evaluation of the stability of Bridgehead Olefins Containing Medium Rings", Bull. Korean Chem. Soc., 1997, 18, 488–495.

- ↑ K. Luong, Molecule 17 Gaussian Output File DOI:10042/193835

- ↑ K. Luong, Molecule 18 Gaussian Output File DOI:10042/193834

- ↑ K. Luong, Computed 1H NMR values

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 L. A. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard and R. D. Rogers, "[3.3] Sigmatropy within 1-vinyl-2-alkenyl-7,7-dimethyl-exo-norbornan-2-ols. The first atropselective oxyanionic Cope rearrangement", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277–283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ja00157a043" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ K. Luong, Computed 13C NMR values

- ↑ G. F. Bauerfeldt, T. M. Cardozo, M. S. Pereira and C. O. da Silva, "The anomeric effect: the dominance of exchange effects in closed shell systems" Org. Biomol. Chem., 2013, 11, 299–308. DOI:10.1039/c2ob26818c

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 E. M. McGarrigle and D. G. Gilheany, "Chromium- and manganese-salen promoted epoxidation of alkenes.", Chem. Rev., 2005, 105, 1563–602.DOI:10.1021/cr0306945

- ↑ E. N. Jacobsen, W. Zhang, A. R. Muci, J. R. Ecker and L. Deng, "Highly enantioselective epoxidation catalysts derived from 1,2-diaminocyclohexane", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 7063–7064.DOI:10.1021/ja00018a068

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 K. Luong, Stilbene Oxide NMR Gaussian Output Files DOI:10042/193927

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 M. W. C. Robinson, K. S. Pillinger, I. Mabbett, D. a. Timms and A. E. Graham, "Copper(II) tetrafluroborate-promoted Meinwald rearrangement reactions of epoxides", Tetrahedron, 2010, 66, 8377–8382.DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2010.08.078 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "1-s2.0-S0040402010013116-main" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ K. Luong, Gaussian Output Files: (R,R) trans-Stilbene Oxide Optical Rotation DOI:10042/193964

- ↑ K. Luong, Gaussian Output Files: (S,S) trans-Stilbene Oxide Optical Rotation DOI:10.14469/ch/189696

- ↑ D. J. Fox, D. S. Pederson, S. Warren, "Diphenylphosphinoyl chloride as a chlorinating agent - the selective double activation of 1,2-diols", Org. Biolmol. Chem., 2006, 4, 3117-3119. DOI:10.1039/B606881B

- ↑ J. Read, I, G, M. Campbell, "The optically active Diphenylphosphinoyl chloride as a chlorinating agent - the selective double activation of 1,2-diols", J. Chem. Soc., 1930, 2377-2384, DOI:10.1039/JR9300002377

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 K. Luong, Dihydronapthalene Oxide NMR Gaussian Output Files DOI:10.14469/ch/189694

- ↑ P. C. B. Page, M. M. Farah, B. R. Buckley and A. J. Blacker, "New Chiral Binaphthalene-Derived Iminium Salt Organocatalysts for Asymmetric Epoxidation of Alkenes.", J. Org. Chem., 2007, 38, 4424–4430.DOI:10.1002/chin.200742093

- ↑ K. Luong, RS Dihydronapthalene Oxide Optical Rotation Gaussian Output Files DOI:10042/193963

- ↑ K. Luong, SR Dihydronapthalene Oxide Optical Rotation Gaussian Output Files DOI:10.14469/ch/189709

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 D. R. Boyd, N. D. Sharma, R. Agarwal, N. a. Kerley, R. A. S. McMordie, A. Smith, H. Dalton, A. J. Blacker and G. N. Sheldrake, "A new synthetic route to non-K and bay region arene oxide metabolites from cis-diols", J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 1994, 1693.DOI:10.1039/c39940001693

- ↑ S. T. Schneebeli, M. L. Hall, R. Breslow and R. Friesner, "Quantitative DFT modeling of the enantiomeric excess for dioxirane-catalyzed epoxidations.", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 3965–73.DOI:10.1021/ja806951r

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Y. Shi, "Organocatalytic asymmetric epoxidation of olefins by chiral ketones.", Acc. Chem. Res., 2004, 37, 488–96.DOI:10.1021/ar030063x

- ↑ R. D. Bach, J. L. Andres, A. L. Owensby, H. B. Schlegel and J. J. W. McDouall, "Electronic structure and reactivity of dioxirane and carbonyl oxide", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1992, 114, 7207–7217.DOI:10.1021/ja00044a037

- ↑ Y. Tu, Z.-X. Wang and Y. Shi, "An Efficient Asymmetric Epoxidation Method for trans -Olefins Mediated by a Fructose-Derived Ketone", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1996, 118, 9806–9807.DOI:10.1021/ja962345g

- ↑ T. Katsuki, "Mn-Salen Catalyzed Asymmetric Oxidation of Simple Olefins and Sulfides.", J. Synth. Org. Chem. Japan, 1995, 53, 940–951.DOI:10.5059/yukigoseikyokaishi.53.940