Rep:Mod:khlmod3

Module 3

The Cope Rearrangement

Introduction

The aim of the first part of this module is to investigate the pericyclic cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene. The investigation of this reaction aims to provide an example for how to analyse a chemical reactivity problem. The mechanism by which the Cope rearrangement proceeds by has been subject to much controversy over the years despite extensive computational investigation. The cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene is a [3,3]-sigmatropic regarrangment whereby three carbon atoms with one olefinic bond migrates across 3 carbons. This reaction occurs under thermal conditions, and with six electrons it conforms to Huckel’s Rules (4n +2), and therefore one can deduce that it proceeds supraficially.

It is now predominantly recognised that the rearrangement proceeds in a concerted manner via the “chair” and “boat” transition structures, where the boat conformation is a few kcal mol-1 higher in energy. The ambiguity surrounding the mechanism of the cope rearrangement and the transition states that it proceeds via, have been attributed to the relative flatness of the potential energy surface curve connecting to two position transition structures. However, literature has found that the DFT (Density Functional Theory) method, using the B3LYP/6-31G* basis set, provides particularly accurate estimates, predicting the activation energies within 1 kcal mol-1 of the experimental values. DFT methods have all demonstrated that the “boat” transition structure is a “looser” transition structure than the “chair” transition structure, and has been found to be approximately 5-6 kcal mol-1 higher in energy [1]. In this module both possible transition structures shall be investigated to support these findings.

Optimisation of the Reactants and Products

The reactants and products were initially drawn in Gaussview 5.0 where each molecule was “cleaned” by ‘editing’ the molecule. Each reactant and product was optimised by created a gif. Input file whereby ‘job type’ was selected as ‘optimisation’, optimised to a minimum, and the method was set to Hartree Fock (HF) using the 3-11G basis set. Each molecule was optimised to a global minimum. Vibrational analysis was used to confirm that the global minimum had been reached, at which point the energies were tabulated. In order to determine the point group of the molecules, the molecule was edited by ‘symmetrize’. The energies and point groups of each reactant and product molecule are tabulated below.

| Conformation | Structure | Jmol | Point Group | Total Energy (Ha) | Relative Energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauche 1 [2] |  |

Jmol | C2 | -231.68771616 | 3.10 |

| Gauche 2 [3] |  |

Jmol | C2 | -231.69166701 | 0.62 |

| Gauche 3 [4] |  |

Jmol | C1 | -231.69266120 | 0.00 |

| Gauche 4 [5] |  |

Jmol | C2 | -231.691530 | 0.71 |

| Gauche 5 [6] |  |

Jmol | C1 | -231.68961574 | 1.91 |

| Gauche 6 [7] |  |

Jmol | C1 | -231.68916015 | 2.20 |

| Anti 1 [8] |  |

Jmol | C2 | -231.69260233 | 0.04 |

| Anti 2 [9] |  |

Jmol | Ci | -231.69253527 | 0.08 |

| Anti 3 [10] |  |

Jmol | C2h | -231.68907064 | 2.25 |

| Anti 4 [11] |  |

Jmol | C1 | -231.69097057 | 1.06 |

The results tabulated above conformed precisely (to five decimal places) with those tabulated in the phys3 appendix 1 and therefore were deemed to be accurate. The results show the gauche 3 conformer to be the most energetically stable with an energy of -231.69266120 Ha, 0.00 kcal mol-1. This is approached with some trepidation, since the 3-11G basis set is very primitive and provides a basic calculation. One would expect an anti-periplanar conformation to be lower in energy, since hyperconjugation and bond-bond Pauli repulsion energy stabilise anti conformers, as indicated by the lecture course on conformational analysis by Henry Rzepa [12]. This said, the gauche conformations do sometimes have access to increased Van de Waals forces, increasing their stability. Therefore, one should consider conducting further analysis to confirm these results. The three lowest energy conformers calculated by the HF/3-11G method were further analysed using a higher level of theory. Therefore the anti 1, anti 2 and gauche 3 conformers were re-optimised using the optimisation job type, where the method was changed to DFT and the method was B3LYP using the 6-31G(d) basis set. To do these calculations the %mem was increased to 500 MB and the link file was changed so as not to overwrite the parent file (the original primitive optimisation). These calculations found that the anti-periplanar conformers are indeed lower in energy than the gauche 3 conformer.as previously discussed the anti conformers are more energetically favourable due to the hyperconjugation within the conformer due to the close alignment of atoms and the stabilising Van de Waals interactions. The DFT calculations, which were conducted using a higher level of theory proved to produce more accurate predictions of the energies one would expect to see experimentally, which correlated with the literature.

| Conformer | Jmol | Point Group | Energy (6-31G* Opt) (Ha) | Relative Energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauche 3 [13] | Jmol | C1 | -234.55993363 | 0.29 |

| Anti 1 [14] | Jmol | C2 | -234.55977103 | 0.00 |

| Anti 2 [15] | Jmol | Ci | -234.55970424 | 0.06 |

MO Analysis

The vibrtaional analaysis carried out on the anti1, anti 2 and the gauche 3 conformers suing the higher level of theory (using the DFT method with B2LYP/6-31G basis set). This allowed one to visualise the molecular orbitals by accessing the checkpoint file from the FREQ calculation and 'editing' the MOs. The HOMO molecular orbitals of the anti 1, anti 2 and gauche 3 conformers are shown below.

| Conformer | HOMO Molecule Orbtial |

|---|---|

| Anti 1 |  |

| Anti2 |  |

| Gauche3 |  |

One can see that there is significant electron density overlap between the orbitals of the two allyl groups in the gauche 3 HOMO, this stabilising pie interaction is not seen in the anti-periplanar anti conformer structures. One can see that after re-optimisation the Van der Waals dispersion forces are still operating on the gauche 3 conformer. These Van de Waals forces result in the ability for H..H interactions resulting in an increased stability of the gauche 3 conformer.

Geometry Comparisons

The geometry of the anti 2 conformer optimised by two different method was compared. The anti 2 conformer was initially optimised using HF/3-21G level of theory, this was then built upon but re-optimising the conformer with DFT theory, using the B3LYP/6-31G basis set. This is assumed to be a higher level of theory that will obtain more precise and accurate results. The table below summaries the bond lengths and bond angles found in the conformer on optimisation, using both methods. The results obtained show that the sp2 C=C bonds become short on re-optimisation with a higher level of theory, reducing from 1.33 Å to 1.32 Å. The sp3 C-C bonds become shorter in between C2-C3 and C4-C5, reducing from 1.54 Å to 1.51 Å, and longer in the centre of the conformer between C3-C4, increasing from 1.51 Å to 1.55 Å. The dihedral angle between C2-C3-C4-C5 remained almost exactly the same, while the dihedral angles between C1-C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5-C6 both decrease. However the changes upon re-optimising with a higher level of theory are small.

| Method | C(1)=C(2) & C(5)=C(6) Bond Length Å | C(2)-C(3) & C(4)-C(5) Bond Length Å | C(3)-C(4) Bond Length Å | C1-C2-C3-C4 Dihedral Angle | C2-C3-C4-C5 Dihedral Angle | C3-C4-C5-C6 Dihedral Angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/3-21G | 1.32592 | 1.54000 | 1.51425 | 119.840° | 179.997° | 115.890° |

| DFT B3LYP/6-31G | 1.31615 | 1.50887 | 1.55290 | 114.670° | 179.974° | 114.670° |

Virbtaiontal Analysis

As previously discussed vibrational analysis of the anti 1, anti 2 and gauche 3 conformers was conducted in order to determine that the conformers had indeed been optimised successfully to a minimum. The checkpoint file for each optimised conformer was used to create a new gif. Input file, where the job type was edited to frequency and a DFT method was selected using the B3LYP/6-31G basis set. All three conformers were found to have been successfully optimised to a minimum since there were no negative frequencies found by vibrational analysis. The spectra is shown below, along with an extract from the log file which demonstrates no negative real frequencies were found and that the low frequencies were all marginally negative, confirming that the minima on the potential energy surface curve has been found. Negative frequencies from vibrational analysis would indicate that a false minimum or a transition state has been found and therefore the optimisation was unsuccessful.

anti1

Low frequencies --- -23.8263 -7.3937 0.0006 0.0008 0.0008 8.4607 Low frequencies --- 72.4492 98.0823 106.7471

anti 2

Low frequencies --- -9.3735 -0.0004 0.0004 0.0009 3.6244 13.1846 Low frequencies --- 71.8977 79.9170 116.8570

Gauche 3

Low frequencies --- -6.1192 0.0006 0.0007 0.0008 6.1738 6.6805 Low frequencies --- 73.4213 100.2986 122.4458

Below is the IR spectrum and the two C=C stretches identified from the vibrational analysis of the anti 2 conformer. The images below demonstrate both the symmetric and anti-symmetric vibrational modes of the C=C bonds found in the anti 2 conformer.

| IR Spectrum of the Anti 2 Conformer | C=C Symmetric Stretch at 1724.63 cm-1 | C=C Anti-symmetric Stretch at 1728.11 cm-1 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Thermochemical Data of the Lowest Energy Conformers

By conducting vibrational analysis for the anti 1, anti 2 and gauche 3 conformers, one can view the thermochemical data. From the log file of each frequency calculation it is possible to extract thermochemical data, which is predicted at 298.15 K. These corrections can also be calculated at different temperatures by editing the input file and adding additional key words “Freq=ReadIsotopes” and editing the input file on wordpad by adding in additional information at the bottom of the input file by stipulating the temperature as 0.0001 K, since 0 could not be entered, and stipulating the exact MW for each atom, where C was 12.0 and H was 1.0.

The thermochemical data taken from the log file for each conformer includes the sum of electronic and zero-point energies, the sum of electronic and thermal energies, the sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies and the sum of electronic and thermal free energies. The sum of the electronic and zero-point energies represents the potential energy at 0 K including the zero-point vibrational energy. The sum of the electronic and thermal energies represents contributions from the translational, rotational, and vibrational energy modes at 298.15 K temperature and 1 atm pressure,. The sum of electron and thermal enthalpies represents a correction for room temperature (H = E + RT) which is particularly relevant when looking at dissociation reactions. The sum of electronic and thermal free energies represents the entropic contribution to the free energy (G = H –TS). These thermochemical values for the anti 1, anti2 and gauche 3 conformers are tabulated below where the [0 K] values were ran at 0.0001 K.

| Conformer | Sum of Electronic and Zero-Point Energies 298.15 K [0 K] | Sum of electronic and Thermal Energies 298.15 K [0 K] | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies 298.15 K [0 K] | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies 298.15 K [0 K] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauche 3 | -234.415744 [-234.415744] | -234.408572 [-234.408572] | -234.407628 [-234.407628] | -234.447180 [-234.447180] |

| Anti 1 | -234.416333 [-234.416333] | -234.409055 [-234.409055] | -234.408111 [-234.408111] | -234.447936 [-234.447936] |

| Anti 2 | -234.416244 [-234.415804] | -234.408954 [-234.406288] | -234.408010 [-234.405180] | -234.447849 [-234.457066] |

The results above are as one would expect. The first value, the sum of electronic and zero-point energies for all three conformers unsurprisingly remains constant between 0 K and 298.15 K. Both the anti 1 and gauche 3 conformers have the same value at both temperatures to six decimal places, while the anti 2 conformer has the same values at both temperatures to three decimal places. The zero-point energy of the system remains constant at all temperatures, and at 0 K all other contributions are zero. This demonstrates that the electronic and zero-point energies remain constant with a variance of temperature as all contributions remain unchanged across all temperatures.

The second value, the sum of the electronic and thermal energies, also remains almost identical as the temperature is reduced from 298.15 K to 0 K. One would expect that on increasing the temperature this value would increase in response to an increase in vibrational, translational and rotational energy contributions. There are obviously no thermal energy contributions at 0 K but one would expect the increase of thermal energy contributions as temperature increases to increase this value.

Thirdly, the sum of the electronic and thermal enthalpies demonstrate no deviation at 0 K and 298.15 K. one would again expect that thermal energy contributions at 0 K would be zero and as the temperature increases one would expect thermal contributions to increase this value.

Lastly, the contributions to free energy one would expect to have no thermal contributions at 0 K. however, as the temperature increases one would expect the contributions to free energy to increases as the degrees of freedom available throughout the molecule increase via rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom.

Analysing the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

This section of the module aims to investigate the “chair” and “boat” transition structures by optimising their structures to the transition state to investigate their relative stability. Optimising to a transition state is far more complex than optimising to a minimum because the calculation needs to know where the negative direction of curvature (the reaction coordinate) is. This module demonstrates the alternative methods one can use to successfully optimise to a transition state. One can initially optimise by computing the force constants using the TS(Berny) calculation with the HF/3-11G method from a “guess” transition state structure. The accuracy of this method depends on the similarity in geometry of the “guess” structure and the actual transition structure. The frozen coordinate method is then used an alternative to this, by using the redundant coordinator editor. Finally, one can then optimise to a transition state by using the QST2 method. These will be discussed in more detail below.

Chair Optimisation

One begins by optimising the “chair” transition structure. Initially the allyl fragment (CH2CHCH2) was drawn in Gaussview 5.0 using the HF/3-21G level of theory. This is half of the transition state structure [16]. The optimised checkpoint file was then opened and a new file was opened. The optimised structure was copied and paste into a new window, by using the edit option, where it was pasted by selecting “append molecule”. This was conducted twice into the same window where the two fragments were moved and rotated so that the form of the transition state shown in appendix 2 of phys3 was visible. The bond distance between the terminal ends of the ally fragments was set to 2.2 Å. This for all intents and purposes is ones “guess” structure.

One can initially optimise to a transition state using the Berny method by computing the force constants using the TS(Berny) calculation with the HF/3-11G method from a “guess” transition state structure. This method is very effective when you have reasonable “guess” transition structure geometry, where one can then compute the force constant matrix in the first step of the optimisation and this will then be updated as the calculation proceeds. However if the “guess” structure is very different from the actual transition structure then this method is not ideal, since the curvature of the surface may be significantly different at point far removed from the transition structure. The “guess” structure obtained by the procedure above is copied and paste into a new window and a gif. Input file is created. A calculation set up is initiated where the job type is set to Opt+Feq, where the structure is optimised to a TS(Berny). The additional words Opt=NoEigen are then also added to prevent the calculation from crashing if more than one imaginary frequency is detected during the optimisation. This optimised successfully, since on obtaining the vibrational data one could see that there was one imaginary frequency, confirming that thee structure had been optimised to a transition state. The bond length between the two terminal atoms of the ally fragments was 2.02 Å which one would expect. As previously discussed above one imaginary frequency was found at -817.81 cm-1, the animation of which is shown below. The imaginary frequency corresponds to the expected value stated in phys3 of -818 cm-1, showing that these calculations were successful. [17].

As an alternative to the Berny method the frozen coordinate method was then explored. In some cases the frozen coordinate method can be more effective where the structure is generated by freezing the reaction coordinate and minimising the rest of molecule. Once the molecule is fully relaxed the reaction coordinate can then be unfrozen and the optimisation can be carried out again. This method can be advantageous when dealing with particularly large molecules; since this method avoids calculating the whole Hessian, as the larger and come complex the molecule the more expensive it is to conduct a force constant calculation. The “guess” transition structure was pasted into a new window and the redundant coordinator editor was selected using the edit option. By using the ‘add’ button two of the terminal carbons on each ally fragment (which would later form a bond) were selected where ‘bond’ was selected rather than ‘unidentified’ and ‘freeze coordinate’ rather than ‘add’. The bond length was also specified as 2.2 Å. This was done for both sets of terminal carbons of the allyl fragments. A calculation set up was initiated where the job type was selected as optimisation, where it is optimising to a minimum. Again the HF/3-11G level of theory is used. The key words “Opt=ModRedundant” is always visible in the input line. This file was submitted to SCAN. The optimised molecule form this method was found to have a bond length of 2.36121 Å and looked very similar to that produced by the previous method [18].

The optimised molecule was then further optimised using the redundant coordinate editor again. By using the ‘add’ button two terminal carbons on the allyl fragments are selected as before and ‘bond’ is selected rather than ‘unidentified’ but this time ‘derivative’ is selected rather than ‘add’. This is repeated with the other bond. The calculation this time is optimised to a transition state as in the Berny method, but this time the force constant are not calculated, so this option is set to ‘never’. The job was submitted to SCAN and the optimised structure was viewed. Again the optimised transition structure looks very similar as before, however the bond length between the terminal carbons of the ally fragments was shortened to 2.02 Å. Vibrational analysis showed that the optimisation to a transition structure had been successful by the presence of one imaginary frequency, corresponding to the bond forming/breaking vibration, which one can see in the animation below. This was found to be at -817.98 cm-1. [19]

Boat Optimisation

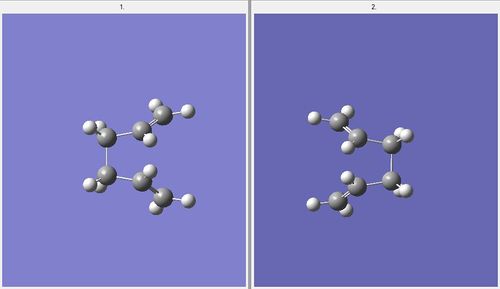

In order to optimise the “boat” transition state both the QST2 and QST3 methods were used. The optimised anti 2 conformer (with the higher level of theory B3YLP/6-31G*) was opened in Gaussview 5.0 and a new window was opened. The optimised anti 2 conformer was copied and paste into the new window and ‘Add to MolGroup’ was selected under file/new, which enables one to view multiple geometries. The reactant molecule is then copied and paste into window 2. By clicking on the ion to show both windows at once it is then possible to rotate and number the molecules. While viewing both molecules simultaneously the molecules are rotated and numbered so they appear as seen in the image below.

This file was then saved as an .gif file and a calculation was made where the job type was Opt+Freq where the file was optimised to a TS(QST2) with the HF/3-21G level of theory. The first optimisation failed since the boat could never be calculated starting from these reactant and product structures. Therefore the structures of both the reactant and product conformations were altered. The dihedral angle of the central four carbon atoms (C2-C3-C4-C5 in the case of the reactant) was altered to 0˚, and the bond angle of central three carbon atoms (C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5 in the case of the reactant) was changed to 100˚. This was carried out for the reactant and product structures. Therefore the conformations appeared as shown below.

This file was subsequently submitted as a .gif input file where the structure was optimised to a TS(QST2) again. This optimisation was successful; producing a structure which one could visibly see had taken up the “boat” structure [20].

The vibrational analysis demonstrated that the transition structure had been indeed found by the presence of one imaginary frequency at -840.91 cm-1, which corresponds to the bond forming/breaking vibration, corresponding to the [3,3]-sigmatropic shift.

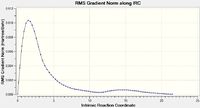

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Calculations for the "Chair" Transition Sate

The intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) method allows one to follow the minimum energy path from a transition structure down to its local minimum on a potential energy surface. This creates a series of points by taking small geometry steps in the direction where the gradient of the energy surface is steepest. The IRc calculation takes the imaginary frequency from the transition state and extrapolates to a lower local energy minimum. This local energy minimum is likely to a conformer of the molecule with undergoes the rearrangement via the chair or boat TS.

The IRC method is approached by using the optimised structures found previously of the “chair” and “boat” structures. A new .gif input file is submitted to SCAN where the job type is selected as IRC. From the options given one selects to compute in the forward direction, since the reaction coordinate in this case is symmetrical, and the force constants are calculated once, at the beginning of the calculation. The IRCMax option could be specified here, this means the calculation will take the transition structure as its input structure and find the maximum energy along a specified reaction path, taking the zero-point energy and so forth into account, producing all the quantities needed for a variational transition state theory calculation. But this is left out for this calculation. Finally, one must consider the number of point along the IRC. When selecting the number of points, 10 points is the default calculation. To begin with one could enter 50 steps along the IRC. The first IRC calculation conducted was on the chair, and various approaches were used until the local minimum was successfully found. The chair transition structure was used initially to determine the best approach in order to reach the local minimum.

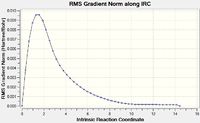

Initially one started with 50 points on the IRC curve. This method terminated after 21 steps and the IRC energy plots and the IRC energy gradient plot indicated that the local minimum hadn’t been reached since the gradient of both IRC graphs didn’t plateau sufficiently. Therefore alternative approaches were then explored. The IRC calculation was re-run but this time the number of points along the IRC was doubled and increased to 100. Similarly, this method terminated after 21 steps and the minimum energies and RMS gradients were very similar as before. Therefore one final method was used, whereby the number of points on the IRC remained at 100; however the force constant was now calculated at every step. Despite taking a little longer than the previous IRC calculations it proved to be the most reliable approach; however it is more expensive and therefore sometime infeasible with larger systems. This method terminated after 47 steps and one can see from the IRC energy plots and IRC energy gradient plots that the energy plateaus significantly, very early on and remains constant, indicating that the local minimum has been found. Altering the IRC approach by increasing the number of points on the IRC can produce the right results however; it is possible that sometimes increasing the number of points on the IRC may just lead to a false local minimum being reached as the calculation goes in the wrong direction.

The results from the three different approaches taken for the "chair" transition structure are tabulated below.

| IRC Calculation | Structure | IRC Energy Plot | IRC Energy Gradient Plot | Minimum Energy | RMS Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRC calculation with 50 steps [21] |  |

|

|

-231.61932200 | 0.00002891 |

| IRC calculation with 100 steps [22] |  |

|

|

-231.61932200 | 0.00002890 |

| IRC calculation with 100 steps computing the force constant at every step [23] |  |

|

|

-231.61932200 | 0.00002890 |

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Calculations for the "Boat" Transition State

Likewise the IRC calculation was carried out on the “boat” transition structure. Similarly the optimised transition structure previously calculated using the QST2 method was opened and a new .gif input file was created. This IRC calculation used the approach found most reliable for the “chair” and therefore the IRC was calculated for the “boat” with 100 point on the IRC and the force constant was calculated at every step. This calculation successfully yielded the local minimum as shown by the results in the table below.

| IRC Calculation | Structure | IRC Energy Plot | IRC Energy Gradient Plot | Minimum Energy | RMS Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRC calculation with 50 steps [24] |  |

|

|

-231.60280100 | 0.00007147 |

Transition State Activation Energies

Finally one needs to look at the activation energies of the “chair” and “boat” transition structures. It is possible to use these calculations to compare the effectiveness of two different computing approaches for optimisation. Therefore, to do this one can take the HF/3-21G optimised “chair” and “boat” structures from above and re-optimise the transition structures using a higher level of theory, using the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* method.

Thus the tables below show the activation energies and the thermochemical data derived by the two different levels of theories allowing one to compare the two methods. In addition, once the calculations had converged successfully it was then possible to look at the difference in energies between the transition structures, which were significant, despite the geometries being relatively similar.

The thermochemical data within the log file of the optimisation of the “chair” and “boat” transition structures and the reactant (conformer anti 2) were extracted, as explained in detail above. To find the activation energies at 0 K and 298.15 K for the “chair” and “boat” transition structures the difference between the respective transition structure energies and the ground state 1,5-heaxadiene (conformer anti 2) energy was found and this was then converted to kcal mol-1, using 1 Ha = 627.509 kcal mol-1. To calculate the activation energies at 0 K the zero-point energies provided by the thermochemical data extracted from the log file were used. Therefore the tables below show the energies calculated by each method and the final table conveys the activation energies calculated at each temperature, by each method after manipulation of the raw data above.

Summary of HF/3-21G Energies

| Conformer | Point Group | Electronic Energy | Sum of Electronic and Zero Point Energies (0 K) | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies (298.15 K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | C2h | -231.61932228 | -231.466700 | -231.461340 |

| Boat | C2v | -231.60280134 | -231.450918 | -231.444348 |

| Reactant(anti 2) | -231.69253501 | -231.539544 | -231.532573 |

Summary of B31YP/6-31G* Energies

| Conformer | Point Group | Electronic Energy | Sum of Electronic and Zero Point Energies (0 K) | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies (298.15 K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | C2h | -234.50546708 | -234.362663 | -234.356754 |

| Boat | C2v | -234.49291456 | -234.351356 | -234.345053 |

| Reactant(anti 2) | -234.55970424 | -234.416244 | -234.408954 |

Summary of Activation Energies in kcal mol-1

| HF/3-21G (0 K) | HF/3-21G (298.15 K) | B31YP/6-31G* (0 K) | B31YP/6-31G* (298.15 K) | Experimental | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE (Chair) | 45.710 | 44.699 | 33.623 | 32.756 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat) | 55.614 | 55.362 | 40.718 | 40.098 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

The resultant activation energies do not correspond well to the literature experimental values when calculated using the HF/3-21G level of theory. However when calculated using the B3LYP/6-31G the values calculated for the activation energies show far better correlation with those specified in literature. This reflects the difference in accuracy of the two different methods and demonstrates that the B3LYP/6-31G level of theory provides significantly greater accuracy in its results. Therefore, according to the data obtained above, the “boat” transition structure is 7 kcal mol-1 higher in energy than the “chair” transition structure. This is what one would expect to find, since as previously discusses above, literature has found that the boat structure is indeed higher in energy and that this energy difference is approximately 5-6 kcal mol-1 which is very close to the figures predicted computationally above by the B3LYP/6-31G method. Therefore, one can conclude that it is more favourable for the Cope rearrangement to proceed via the chair transition structure and will twist into the gauche 2 conformer to make this possible.

A possible cause for this energy difference could be the interaction between the HOMO and LUMO molecular orbitals of the two allyl fragments of the “boat” transition structure. This interaction is slightly anti-bonding in nature and this will therefore destabilise this transition structure. This interaction is not seen in the chair transition structure.

Diels Alder

The Diels Alder reaction is a well-researched pericyclic reaction, first discovered in 1928. The reaction proceeds by a [π4s+π2s]-cycloaddition, whereby the dieneophile contributes 4π electrons and the diene contributes 2π electrons. The total electron count is six and proceeds under thermal conditions and therefore conforms to Huckel’s rules (4n + 2), where n=1. This means that the reaction consists of only suprafacial components. The stereochemistry of this reaction depends on whether the new bond is formed on the bottom of the face or the top of the face the alkene and therefore the reaction can proceed via either the endo or the exo transition structure. Literature suggests that the endo product (where the new bond is formed on the bottom face of the alkene) is more energetically favourable than the exo product (where the new bond is formed on the top face of the alkene). The π orbitals of the dieneophile form new σ bonds with the π orbitals of the diene. If the reaction can proceed in a concerted stereospecific way because the HOMO and LUMO of one fragment can interact with the HOMO and LUMO of the other reactant the reaction will be allowed to proceed, thus forming two new molecular orbitals, one bonding and one anti-bonding. This interaction of the HOMO and LUMO of the reactants can only occur when there is significant electron density overlap. Therefore if the HOMO and LUMO orbitals have different symmetry then no overlap in the electron density will be possible and the reaction will be forbidden.

In this part of the module one will explore the relative stereochemistry of the two transition structures and the effect they have on the reactivity of the reaction. The reaction considered below is between maleic anhydride (dieneophile) and cyclohexadiene (diene). Therefore in this case the dieneophile and diene are both substituted. It is often the case that when the dieneophile has substituents that have π orbitals, these can interact with the new bond being formed in the product, which can stabilise the regiochemistry of the reaction. This will be explored below.

Optimisation of Cis-Butadiene and Ethene

Cis-butadiene and ethane were both drawn out in Gaussview and optimised. To do this the AM1 semi-empirical method was used. This calculation was done by an Opt+Freq job type which then allowed one to decipher if the optimisation had been successful by the presence or absence of negative vibrational modes. These optimisations were successful since there were no negative frequencies. The HOMO and LUMO molecular orbitals were visualised using the checkpoint file for both molecules and are tabulated below, where the symmetries of the MOs are shown with respect to the plane of symmetry.[25][26]

| HOMO of Cis-Butadiene Antisymmetric | LUMO of Cis Butadiene Symmetric | HOMO of Ethene Symmetric | LUMO of Ethene Antisymmetric |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

The symmetry of the HOMO and LUMOs of the cis-butadiene and the ethene show that the reaction is allowed and will proceed since the HOMO of the cis-butaidene and the LUMO of the ethene are of both antisymmetric while are the LUMO of the cis-butadiene and the HOMO of the ethene are both symmetric. As previously discussed for the reaction to proceed, the molecular orbitals of the reactants must be of the same symmetry in order for there to be sufficient electron density overlap between the orbitals for a new bond to be made. Therefore the above symmetry of the molecular orbitals demonstrates that the reaction will be stabilised by the electron density overlap made possible by their shared symmetry. No electron density overlap can occur where the symmetry of the molecular orbitals is different.

Computation of Transntion State Geometry

The optimised cis-butadiene and ethene fragments as before were copied and paste into a new window to create the transition state. The two fragments were orientated to a position thought similar to the transition state where the two terminal carbons on each fragment were set 2.0 Å apart. The Berny method was used to find the transition state, and initially the HF/3-21G level of theory was used to gain a rough estimate of the transition structure from the “guess” structure. The structure obtained was then re-optimised using a higher level of theory using the DFT method with the B3LYP/6-31G basis set. Vibrational analysis was then subsequently conducted on both transition structures produced by both methods to confirm that the transition structure has indeed been found. This was indicated by the presence of one imaginary vibrational mode. The imaginary frequency vibrations are depicted below, illustrating the bond forming and bond breaking vibration. In order to see the animation please click on the images below.

| Method | Structure | Jmol | Imaginary Frequency cm-1 | Image of Imaginary Frequency (Click on image to see animation) | Lowest Frequency cm-1 | Image of Lowest Frequency (Click on image to see animation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS(Berny) with HF/3-21G [27] [28] |  |

Jmol | -818.46 |  |

166.62 |  |

| TS(Berny) with DFT/6-311G [29] |  |

Jmol | -534.69 |  |

139.72 |  |

DFT method: Bond separation = 2.26351 Å Ethene sp<sub>2</sub> = 1.39260 Å Butadiene sp<sub>2</sub> = 1.38871 Å Butadiene sp<sub>3</sub> = 1.40810 Å

HF/3-21G method: Bond separation = 2.20938 Å Ethene sp<sub>2</sub> = 1.37589 Å Butadiene sp<sub>2</sub> = 1.37000 Å Butadiene sp<sub>3</sub> = 1.39440 Å

Both structures demonstrated the expected envelope structure with the bond distance between the two terminal carbon atoms of the two fragments at 2.2 Å. The concerted vibrations shown above are as one would expect. Both imaginary frequencies found, illustrating the bond breaking and bond forming vibration, are symmetric, in that both fragments move in a concerted manner away and toward each other simultaneously and therefore the formation of the bond is synchronous. The presence of an imaginary frequency in both methods demonstrates that the transition structure was reached.

As demonstrated above, the first optimisation using the HF/3-21G level of theory found only one negative frequency, the imaginary frequency, corresponding the reaction path at the transition, at -818.46 cm-1. The lowest positive frequency was found to be at 166.62 cm-1, as shown above. The cis-butadiene sp2 C=C bond lengths were modelled as 1.37000 Å and the sp3 C-C bond as 1.39440 Å. The ethene sp2 C=C bond was modelled as 1.37589 Å. The separation of the terminal carbon atoms of the two fragments was modelled as 2.20938 Å.

Similarly, the higher level of theory (DFT, B3LYP/6-31G) found only one negative frequency, the imaginary frequency, at -534.69 cm-1, whilst the lowest positive frequency was found to be 139.72 cm-1. The cis-butadiene sp2 C=C bond lengths were modelled as 1.38871 Å and the sp3 C-C bond as 1.40810 Å. The ethene sp2 C=C bond was modelled as 1.39260 Å. The separation of the terminal carbon atoms of the two fragments was modelled as 2.26351 Å.

As one would expect the sp2 bonds were calculated to be shorted than the sp3 bonds in both cases. In addition to this, one would expect the sp3 bond lengths to be longer in the transition state and the sp2 bonds to be longer than 1.35 Å, which was observed in the calculations above. The bonds lengths calculated in the transition state are therefore intermediate of literature bond lengths that literature suggests [30] [31]. An explanation of this could be that there is some disruption in the π-bonding of the reactants and this could then affect the hyperconjugation of the carbon atoms in the fragments. In addition to this, a transition from sp2 hybridised carbon atoms to sp3 hybridised carbon atoms confirms the previous assumption that this is a cycloaddition.

Furthermore, the distances between the terminal carbon atoms on the two fragments, 2.26 Å and 2.21 Å, suggest the partial formation of the new sp3 C-C bond between the two fragments since this distance, in both cases, is below the doubled Van de Waals radii of carbon atoms which are generally accepted as 3.14 Å. It should also be noted that the bond distances of the terminal carbon atoms of the two fragments are exactly the same for both sets of terminal atoms, again confirming the concerted nature of the reaction.

The molecular orbitals were then visualised from the checkpoint file of the optimisation, looking at the HOMO and LUMO of the transition structure in particular. The HOMO and LUMO molecular orbitals of the transition structures calculated by the two methods are therefore shown below.

| HOMO using HF/3-11G Antisymmetric | LUMO using HF/3-11G Symmetric | HOMO using DFT/6-31G Antisymmetric | LUMO using DFT/6-31G Symmetric |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Form the molecular orbitals shown above one can see that the antisymmetric cis-butadiene HOMO and the ethene antisymmetric LUMO overlap to form the antisymmetric HOMO in the transition structure, thus preserving the symmetry. Furthermore the HOMO shows that the new sp3 C-C σ bond formed between the two fragments is a consequence of the interaction between the π orbitals in the cis-butadiene fragment and the π* molecular orbitals in the ethene fragment.

It can also be seen that the symmetric LUMO molecular orbital in the transition structure is formed by the overlap of the symmetric LUMO π* fragement orbital of the cis-butadiene fragment and the symmetric HOMO π fragment orbital of the ethene fragment to form the new sp2 C=C bond in the butadiene, again preserving the symmetry. In addition to this, the suprafacial overlap of the orbitals in the HOMO molecular orbitals conforms to Huckel’s rules, which state that 4n+2 pericyclic reactions under thermal conditions consist of only suprafacial components in the transition state.

Analysis of Regioselectivity of Diels Alder Reaction

The regioselectivity of the Diels alder reaction was then explored using maleic anhydride (dieneophile) and cyclohexadiene (diene), where both the diene and dieneophile are substituted. This reaction is known to proceed via kinetic control and therefore primarily give the endo adduct, with the exo transition structure being higher in energy. The two mechanisms for the formation of both the exo and endo adduct are shown below.

In order to accurately model the transition structures for this reaction the reactant were initially optimised individually. Therefore cyclohexadiene [32] and maleic anhydride [33] were both separately drawn in Gaussview and optimised using the semi-empirical method AM1. The reactants successfully optimised and their molecular orbitals were then visualised using the checkpoint file, where one could see if the optimisation yielded sensible results. The HOMO and LUMO of both reactants are shown below.

| HOMO of Cyclohexadiene | LUMO of Cyclohexadiene | HOMO of Maleic Anhydride | LUMO of Maleic Anhydride |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

As before the two optimised reactants were copied and paste into a new window were they were orientated into a position relative to each other which was thought to be similar to that of the transition state. They were arranged so that either the double bonds of the cyclohexadiene were above the oxygen groups of the maleic anhydride (in the case of the endo transition state), or where the oxygen groups of the maleic anhydride faced in the opposite direction to the double bonds in the cyclohexadiene (in the case of the exo transition state). The double bond in the maleic anhydride was position roughly below the central two carbon atoms in the six membered ring (1 and 4 positions), where the new bonds would be forming in both cases. Thus two “guess” structures were created and these were then optimised to their respective transition states. To do this the frozen coordinate method was utilised. Initially both structures (endo [34] and exo [35]) were optimised to a minimum, where the redundant coordinate editor was used to freeze the two bonds that would be formed in the product. The calculation therefore had the key words Opt=ModRedundant already in the input line. Once this calculation succeeded the structure was again optimised, but this time it was optimised to a TS(Berny) where the force constants were never calculated and the two bonds which were previously frozen were changed from ‘add’ to ‘derivative’. This gave the final optimised transition structure for both the exo [36] and endo [37] forms. However in order to confirm that the transition structures had indeed been found, vibrational analysis was conducted by doing a further frequency calculation where the semi-empirical method AM1 was again used for both the exo [38] and the endo [39] transition structures. The results of these calculations are tabulated below.

| Transition State Approach | Jmol | Energy (Ha) | Optimised bond break/making Separation Å | Lowest Frequency cm-1 | Imaginary Frequency cm-1 | Image of Imaginary Frequency (Click on image to see animation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo | Jmol | -605.60358970 | 2.17 | 41.99 | -647.63 |  |

| Endo | Jmol | -646.30 | 2.16 | 66.20 | -646.30 |  |

From the table above one can see that the transition structure for both the endo and exo form was indeed found, confirmed by the presence of one negative frequency, the imaginary frequency, for each structure. The vibration of these vibrational modes are shown in the table above which display the bond break and bond forming vibration that one would expect to see in a transition structure. The lowest positive frequencies were also found; aside from the imaginary frequency all other frequencies were sufficiently positive indicating that the calculation had been successful.

As one can see from the animations of both imaginary frequencies the vibrations show the symmetric and synchronous bond forming the sp3 σ C-C bonds between the fragments, indicating that this pericyclic reaction is indeed concerted as one would expect. This is additional supported by the bond breaking and bond making distances between the two fragments being uniform for both bond being made. Furthermore, one can also see that the transition structure leading to the endo product has a much lower energy than the transition structure leading to the exo product, -605.6 Ha versus -646.3 Ha, this supports the notion that the endo product is the primary product.

The MOs calculated from the optimised transition structures for the exo and endo form are shown below.

| Transition State | HOMO Anitsymmetric | HOMO-1 Symmetric | LUMO Antisymmetric | LUMO+1 Symmetric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo |  |

|

|

|

| Endo |  |

|

|

|

The LUMO+1 MO of the endo transition structure illustrates orbital interactions between the C=O pie bonds of the maleic anhydride fragments and the C=C pie bonds of the cyclohexadiene, which in the endo approach both have the same symmetry and therefore the electron density of the orbitals can overlap, which is not possible in the exo form. On close inspection of the LUMO+1 MO one can see that it is very slightly bonding. The second orbital interaction could be a consequence of occupation of the molecular orbital and would support the shorter C-C bond separation between the fragments in the endo form when compared to the exo form.

The IRC pathway was calculated for the endo and exo transition states to confirm an actual transition state. This calculation was done by calculating the force constant at every step, and manually selecting the number of steps on the IRC to 100 to ensure that the local minimum was found, this was done in the forward direction only. This was done using the semi-empirical method AM1 and the checkpoint file was subsequently optimised to ensure that the endo and exo product had been found.

| Transition Structure | Jmol | IRC Energy Plot | IRC Energy Gradient Plot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exo [40] | Jmol |  |

|

| Endo [41] | Jmol |  |

|

Conclusion

Normal 0 false false false EN-GB X-NONE X-NONE MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

From the calculations above using the semi-empirical method and the DFT approach, once can conclusively see that the endo approach is primarily produced during the reaction between maleic anhydride and cyclohexadiene. Despite the increased steric strain present in the endo form, the endo form remains more favourable due to the secondary orbital interactions present between the pie systems of both reactants, leading to the increased stabilisation of the endo form over the exo form. It should be taken into consideration that these calculations are carried out using the semi-empirical method and that for greater accuracy and precision of results a higher level of theory could be used to explore these findings further and quantify the energy difference between the two transition states further.

References

- ↑ O. Wiest, K. A. Black, K. N. Houk, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116, 10337 DOI:10.1021/ja00101a078

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11234

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11235

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11236

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11237

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11238

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11239

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11242

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11243

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11241

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11240

- ↑ Henry Rzepa, Conformation Analysis 2nd Year Lecture Course

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11262

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11260

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11261

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11263

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11264

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11265

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11253

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11255

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11266

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11267

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11268

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11269

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11281

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11280

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11279

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11375

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11376

- ↑ Stoicheff, B.P., Tetrahedron, 1962, 17, 135-145

- ↑ J. Breulet, H. F. S. III, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1984, 106, 1226

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11377

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11384

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11426

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11428

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11401

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11400

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11403

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11402

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11435

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11436