Rep:Mod:js3311y31c

Year 3 Chemistry Laboratories Computational Assignment 1C

The use of computational calculations had enabled people to rationalise various experimental observation as well as to predict likely structural conformation of new compounds.[1] This assignment is one of the two-pronged approach into understanding the epoxidation of various alkenes that were performed in the synthesis laboratory. Prior to the computational studies done on the epoxide, other computational experiments were carried out using Avogadro and various other platforms. Thereafter with these skill sets, a computational experiment was done on the epoxidation of alkenes.

Part 1

Conformational Anaylsis Using Molecular Mechanics

The first exercise involved the use of Avogadro for conformational studies of various compounds. Energy calculations provide a theoretical understanding of which conformation would be preferred (usually the conformer with the lowest energy). However, experimental observations can differ from these computational calculations and these are reconciled by the understanding of the mechanisms of the processes that lead to products.

Conformation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

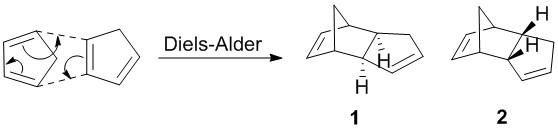

Cyclopentadiene are known to exist as a dimer as they readily undergo Diels-Alder reaction to form the dimer. As with many other Diels-Alder reaction, there are stereoselectivity concerns with the reaction; the exo (1) or endo (2) product may be formed. This selectivity arises due to the preference to form either the kinetic or thermodynamic product, where the kinetic product is formed due to the stability of the transition state, thereby lowering the activation energy. On the other hand, the thermodynamic product is formed as it is the lower energy isomer of the two. Scheme 1 shows the two stereoisomers that may form.

Scheme 1: Diels-Alder Reaction between two cyclopentadiene to give either 1 or 2

This section aims to investigate the conformation of the two cyclopentadiene 1 and 2 by analysing various aspects of the energy contribution to the compounds via computational methods. With the use of Avogadro, both 1 and 2 were optimised and their energies calculated using the MMFF94s force field. The results were tabulated in Table 1 below.

| Isomer | Bond Stretching (kcal/mol) |

Bending (kcal/mol) |

Torsion (kcal/mol) |

Non-bonded (kcal/mol) |

Electrostatic (kcal/mol) |

Total (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.54179 | 30.77496 | -2.71518 | 12.78657 | 13.01335 | 55.37503 |

| 2 | 3.46756 | 33.19461 | -2.94714 | 12.3553 | 14.18092 | 58.19091 |

As shown, the exo dimer 1 has the lower overall energy in comparison against the endo dimer 2. This corresponds to the exo dimer 1 being the thermodynamic product that resulted from the Diels-Alder reaction. Despite this, experimental observation had shown that only the higher energy-endo dimer 2 is formed.[2] This preferred conformation is due to the stability of the endo transition state where the adjacent p orbitals of the diene would interact with that of the dienophile as shown on Scheme 2. Hence it can be concluded that this reaction is kinetically driven as it is stabilised during the transition state by orbital interactions.

Scheme 2: Orbital stabilisation leading to the formation of only the endo dimer 2

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

The previous section have demonstrated that reactions can lead to kinetic or thermodynamic products, and this can be rationalised using the predicted energies of the two isomers via computational calculations. The same principle can be applied with the hydrogenation of the cyclopentadiene dimer 2. Hydrogenation of 2 will initially lead to only one of the two alkene bonds being hydrogenated (3 or 4) before the tetrahydro product 5 is obtained upon further hydrogenation.

Scheme 3: Hydrogenation of 2 to give either 3 or 4 before obtaining 5

A computational calculation can be done to predict the thermodynamic product of the reaction of 2 to either 3 or 4 by analysing which compound would give the lower energy regioisomer. Structures were similarly optimised using the MMFF94s force field on Avogadro and the energies are obtained. The result of the calculation is summarised in the table below.

| Bond Stretching (kcal/mol) |

Bending (kcal/mol) |

Torsion (kcal/mol) |

Non-bonded (kcal/mol) |

Electrostatic (kcal/mol) |

Total (kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.31163 | 31.93445 | -1.46930 | 13.63842 | 5.11949 | 50.44565 | |

| 2.82040 | 24.70273 | -0.36950 | 10.61385 | 5.14714 | 41.25873 | |

| Difference (3-4) |

0.49123 | 7.23172 | -1.0998 | 3.02457 | -0.02765 | 9.18692 |

Therefore by comparing the total energy of 3 and 4, 4 gave the lower overall energy and thus would be predicted to be the thermodynamic intermediate before obtaining the tetrahydro derivative 5. By comparing the different energy contributions, the bending energy is the biggest contribution to the thermodynamic stability of 4 over 3. Both 3 and 4 possess a 6-membered ring locked in a boat conformation due to the presence of a bridgehead carbon. However, presence of a double bond in the 6-membered ring of 3 could lead to higher rigidity due to the sp2 carbons, where the boat conformation is a slightly unnatural conformation. The other significant difference would be the non-bonded energy levels between the two isomers, where 4 experience less van der Waals repulsion that 3 would. By visual comparison of the spacial distribution of the hydrogen molecules in 3 and 4, the hydrogen molecules on the 6-membered ring is likely to experience less repulsive interaction with adjacent hydrogen molecules in comparison to that on the adjacent 5-membered ring.

Taxol is a compound extracted from plants and has been known to have anticancer properties and possesses the ability to inhibit tumours.[3] In the total synthesis of taxol, Paquette proposed two intermediates 6 and 7. They are atropisomers of each other, of which one is lower in energy than the other. For the purpose of this study, the stability of the two isomers 8 and 9 were compared instead.

Using the same procedures as above, the MMFF94s force field was employed to optimise the structure and their energy values were calculated and tabulated in Table 3.

| Compound1 | Total (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| 70.53974 | |

| 77.89927 | |

| 60.55099 | |

| 66.28752 |

1a = 6-membered ring in chair conformation

b = 6-membered ring in twist-boat conformation

The main factors that affect the stability of the isomer would be 1) the conformation of the 6-membered ring and 2) atropisomerism due to the position of C=O bond. The energy difference due to the conformation of the 6-membered ring can be compared between a and b while the energy difference due to atropisomerism can be compared between 8 and 9. With that, from Table 3, it can be seen that isomer 9a is the most stable isomer with an energy of 60.55099 kcal/mol. In consideration of the conformation of the 6-membered ring, two energy wells were observed in the energy profile of cyclohexane - chair and twist-boat conformation[4]. The calculations above has thus shown that the chair conformation is indeed the lower energy conformation. A further investigation into the different energy contribution to the stability of the intermediates revealed that the stability due to atropisomerism could be attributed to the difference in the bending energy of the molecule, which contributed to 95 % of the difference in total energy. This could suggest that the dihedral angle of various bonds within 8a were out of the natural bond angle (~109 ° about an sp3 hybridised orbital, ~120 ° about an sp2 hybridised orbital), causing a strain in the bond which gave rise to an increase in energy.

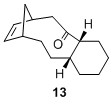

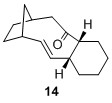

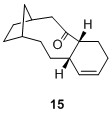

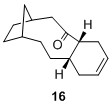

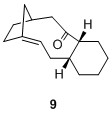

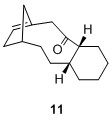

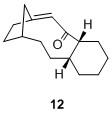

These compounds belong to a group of olefins known as "bridgehead olefins" due to the presence of a double bond at the junction of the bridgehead. Some of these compounds present extra stability for which Schleyer termed them "hyperstable bridgehead olefins". [5] These bridgehead olefins are exceptionally stable due to the "cage structure" that these alkenes possess.[5] In addition, the corresponding cycloalkane would have a higher strain and therefore lead to higher energy product, which is not favourable.[5] Thus to ascertain the stability of such bridgehead olefins, two sets of calculations were performed and compared against the bridgehead olefin 9a. The first of which is the calculation of total energies of various bridgehead olefin regioisomers and next would be the total energies of other possible regioisomers with the double bond not involving the bridgehead carbons. The purpose of this calculation is to ascertain the claim that these bridgehead olefins are indeed much more stable than other regioisomers. All calculations were performed on molecules with the 6-member ring in the chair isomer to ensure consistency. The result is tabulated in the table below:

It is interesting to note that of the 4 possible bridgehead olefin regioisomers, 10 had a very similar total energy as 9a at 60.47844 kcal/mol. However both 11 and 12 have much higher energy at 83.38447 and 88.03254 kcal/mol respectively. One plausible qualitative explanation would be the distortion of the alignment between the 2 σC-H orbitals with the σ*C-O, where in the 11 and 12, one σC-H orbital is misaligned and hence there will be far less orbital interaction thus gave rise to less stabilising energy. It can also be seen that the other regioisomers 13 to 16 possessed higher energy values compared to the bridgehead olefins 9 and 10. This has thus substantiated Schleyer's claim that bridgehead olefins possess stabilising effect when compared to other possible regioisomers.

Schleyer also claimed that the energy of the bridgehead olefins are lower than the corresponding cycloalkane. Therefore the second set of calculation aims to confirm this claim. Using the same force field for a simple hydrogenation process, the energy levels of the 4 possible bridgehead olefins were compared against the hydrogenated derivative 17 and the results were tabulated in Table 5.

| Compound | Total Energy (kcal/mol) |

Compound | Total Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

60.55099 |  |

83.38447 |

|

60.47844 |  |

88.03254 |

|

69.53460 |

With the exception of 11 and 12, the other two bridgehead olefins 9 and 10 are indeed lower in energy than the corresponding cycloalkane 17. The anomalies observed for 11 and 12 could be due to the same explanation given above; the lost of the stabilising effect by the adjacent orbitals led to 11 and 12 being higher in energy than the corresponding cycloalkane.

Spectroscopic Simulation Using Quantum Mechanics

Computational studies can also be used to predict various spectroscopic data. In this section, computational calculation is performed on another taxol intermediate 18[6][7] to obtain the predicted 1H and 13C spectral data. The molecule was first optimised using the MMFF94s force field and then submitted for calculation via High Performance Computer (HPC) on the college server. The calculated chemical shifts were compared against the literature values and discussed below.

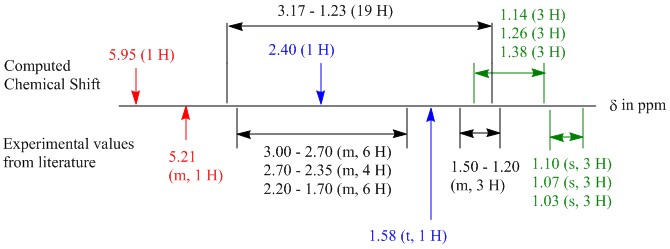

1H NMR Analysis

The predicted NMR values had to first be processed before obtaining the final values. The calculation was done on the assumption that all terminal methyl groups do not experience free rotation, resulting in all germinal hydrogens on these carbons having different chemical shifts. Thus these values were averaged before being tabulated. Furthermore, due to the cyclic nature of the compound, the hydrogens along the cyclic ring were locked in conformation and thus experience germinal (2J) coupling in addition to the usual 3J coupling, which give rise to complicated multiplets as assigned in the literature. With that we can only make the following comparison based on protons that can be identified:

1) Chemical shifts of protons on carbon 5, 6, 13 can be compared (after being averaged) against those of the literature where the chemical shifts are at 1.10, 1.07 and 1.03 ppm. It is to note however, that the absolute assignment of these three chemical shifts to a specific carbon may not be possible due to the similarity in the environment of which the methyl groups belong to. Therefore these 3 values are compared together.

2) Vinylic proton on carbon 9 has a characteristic chemical shift in the region of 5 to 6 ppm. This would thus correspond to the only chemical shift observed at 5.21 ppm in the literature.

3) Hydrogen on carbon 14 would give rise to a triplet (or double doublets if the two hydrogens are in different environments) due to 3J with adjacent hydrogens on carbon 10. This would thus correspond to the chemical shift at 1.58 ppm reported in the literature.

4) Anything else can only be estimated based on prior knowledge of similar compounds/environment of which these hydrogens belong to.

With that in mind, the computed values are compared against the literature values[8] and succinctly presented in a diagram (Figure 1) to illustrate the contrast between the two sets of values.

Figure 1: Illustration of comparison between literature 1H NMR and computed values of 18a

From the above it can be seen that the coloured values in Figure 1 correspond to the points 1 (green), 2 (red) and 3 (blue) above. There are a few plausible suggestions for this difference. One of which could be because that the molecule obtained is not at the lowest possible conformation due to the limitations of the method used in this computational study. Another reason could be that the molecule adopts a higher energy conformation. This is similar to the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene.

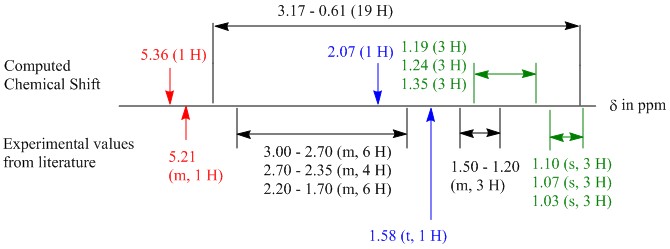

Thus to ascertain this claim, the process was repeated with the 6-membered ring in a twist boat conformation. Subsequent optimisation using the MMFF94s force field forced the 6-membered ring into a boat conformation instead. The NMR of the final conformation was then calculated via the HPC and the results presented in a similar structure to Figure 1 as given below:

Figure 2: Illustration of comparison between literature 1H NMR and computed values of 18b

The boat conformation 18b showed that the values that are coloured are closer to the reported values. However, the other values were spread over a larger range from 3.17 - 0.61 ppm as compared to 18a. This is because the carbons in the ring bearing the hydrogens are conformationally locked and thus 2 geminal hydrogens can have different chemical shift, thus spreading over a large range of chemical shifts. This may not be the case in the literature where the germinal 2J coupling is negligible. Due to the complicated multiplets observed in literature, germinal 2J coupling cannot be established.

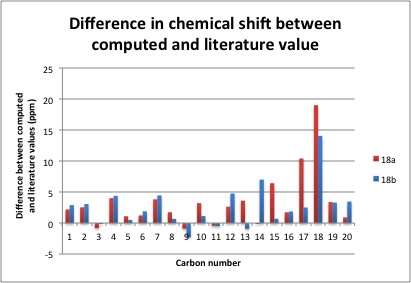

13C NMR Analysis

Similar to the computed 1H NMR values, the computed values had to be processed, albeit via a different method. The 20 chemical shifts were compared against the literature values and the difference (Predicted - Literature) were measured and presented in the graph below (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Graphical comparison of 13C NMR values between literature and the predicted values of 18a and 18b

It is shown on the graph that most chemical shifts were overestimated for both 18a and 18b. From the analysis of 1H NMR data, it can be seen that 18b is in closer agreement with the literature values. This is also the case for 13C NMR. All predicted chemical shifts are within ± 5 ppm of the literature values with the exception of carbon 15, 17 and 18 for 18a and carbon 14 and 18 for 18b. Predicted values of 18a have a larger deviation compared to 18b, suggesting that 18 may not adopt a chair conformation at the 6-membered ring. The abnormally large difference at carbon 14 and 18 could be best accounted for by the proximity of the carbon to heavy atoms, where carbon 14 is 3 bonds away from an oxygen and 2 bonds away from 2 sulphur atoms, while carbon 18 is directly bonded to 2 sulphur atoms. Corrections are required to be made in order to present a more accurate model.[9]

Part 1 References

- ↑ Rappe, A. K.; Casewit, C. J.; Colwell, K. S.; Goddard, W. A.; Skiff, W. M. UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10024–10035. DOI:10.1021/ja00051a040

- ↑ Cristol, S. J.; Seifert, W. K.; Soloway, S. B. Bridged Polycyclic Compounds. X. The Synthesis of endo and exo-1,2-Dihydrodicyclopentadienes and Related Compounds 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 2351–2356. DOI:10.1021/ja01494a060

- ↑ Wani, M. C.; Taylor, H. L.; Wall, M. E.; Coggon, P.; McPhail, A. T. Plant antitumor agents. VI. Isolation and structure of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2325–2327. DOI:10.1021/ja00738a045

- ↑ Squillacote, M.; Sheridan, R. S.; Chapman, O. L.; Anet, F. A. L. Spectroscopic detection of the twist-boat conformation of cyclohexane. Direct measurement of the free energy difference between the chair and the twist-boat. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 3244–3246. DOI:10.1021/ja00844a068

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Maier, W. F.; Schleyer, P. V. R. Evaluation and prediction of the stability of bridgehead olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 1891–1900. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "bridgehead olefins" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Soo, J. Taxol Intermediate 18 chair NMR. D-Space, 2014 DOI:10042/27507

- ↑ Soo, J. Taxol Intermediate 18 twist-boat NMR. D-Space, 2014 DOI:10042/27508

- ↑ Paquette, L. A.; Pegg, N. A.; Toops, D.; Maynard, G. D.; Rogers, R. D. [3.3] Sigmatropy within 1-vinyl-2-alkenyl-7,7-dimethyl-exo-norbornan-2-ols. The first atropselective oxyanionic Cope rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 277–283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ Braddock, D. C.; Rzepa, H. S. Structural reassignment of obtusallenes V, VI, and VII by GIAO-based density functional prediction. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 728–30. DOI:10.1021/np0705918

Part 2

This section aims to look closely into the chemistry of the epoxidation processes that were carried out in the undergraduate laboratory sessions. Various in-depth investigation into the chemistry was made via computational methods, part of which also include the studying of the structure of the two catalysts employed - Jacobsen's and Shi catalysts. The predicted 1H and 13C NMR for the epoxides were obtained using the same method of calculation for which the predicted NMR spectra for 18 were obtained. Finally, a closer look into the study of transition state of the reaction was done by looking at the non-bonding interaction between the 2 molecules and finally an analysis of the electronic topology is carried out.

Structural Analysis of Catalysts

In the laboratory, epoxidation reactions were carried out using 2 asymmetric epoxidation catalysts - The Jacobsen's and Shi catalysts. Both catalysts carry out the similar epoxidation reaction on alkenes. However as suggested that they are asymmetric epoxidation catalysts, they have different selectivity towards different geometrical isomers of alkenes; Jacobsen's catalyst is known to have a cis selectivity for alkenes[1] whereas the Shi catalyst have a trans selectivity[2]. The reason for this selectivity can be rationalised by looking at the structure of the catalysts. The structure of these two known catalysts were found using the Cambridge crystal database (CCDC) on ConQuest and then analysed using Mercury.

Shi Catalyst

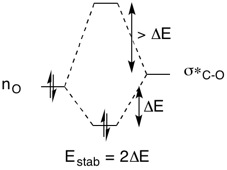

The Shi catalyst is a catalyst derived from fructose.[3] The epoxidation proceeds via a dioxirane intermediate in presence of oxone which will then transfer the oxygen atom over to the alkene, forming the epoxide.[3] One significant feature observed in the Shi catalyst is the anomeric effect. The anomeric effect arises due to the interaction of the lone pair on the oxygen with the σ*C-O orbital adjacent to it in an antiperiplanar relationship. This leads to the preferential alignment of the C-O bond in the axial position with respect to the 6-member ring in the Shi catalyst. Whilst the lone pair is also able to interact with the σ*C-C orbital, it is higher in energy than σ*C-O orbital thus from the Klopman-Salem equation, there will be lesser stabilisation as the overlap integral is smaller. The overall stabilisation is illustration in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Stabilisation of energy level due to anomeric effect

In addition, due to the donation of electron density from the oxygen lone pair to the σ*C-O orbital, it should cause a lengthening of the C-O bond. However, when comparing the C-O bond length in the catalyst, not all C-O bonds that experience the anomeric effect have an increased C-O bond length. For the purpose of comparison, a typical C-O bond length in ether is taken to be 1.42 Å.[4] The various C-O bond length is shown in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Various C-O bond length of Shi catalyst in Angstroms (Å)

From the figure it can be seen that there are two C-O bonds at 1.454 Å and 1.456 Å are longer compared to a typical C-O bond length at 1.42 Å. This is due to the antiperiplanar relationship between C-O and the oxygen lone pair. It is also interesting to note that while the anomeric effect is observed in the Shi catalyst, the C-O bond length on the fructose 6-member ring did not lengthen as predicted. This could indicate that there may be a lack of anomeric interaction within the 6-membered ring. One plausible reason would be the lack of antiperiplanar relationship between the orbitals involved due to the presence of the two 5-membered ring adjacent to it, which may force the substituent groups to twist out of position.

Another interesting feature would be the 4 C-O bond lengths on the two 5-membered rings. All 4 C-O should experience the anomeric effect due to the presence of the lone pair on the adjacent oxygen. However, only one C-O bond in each of the 5-membered ring experienced an increase in bond length. A similar explanation of the misalignment of the orbitals may be used, albeit it being a mere qualitative explanation and further investigation may be required to fully account such observation.

Jacobsen's Catalyst

Analysis of the distance between the two tBu groups on either phenyl rings reveal that the distance between them is 2.08 Å (can be measured in the Jmol file on the right). This is within the van der Waals radius of the hydrogen atoms [5] and thus presents as a very favourable interaction which arose form London dispersion forces of interaction. This would therefore result in a closure of the plane of which the ligand is situation and prevent any approach by alkenes in that direction. This would therefore restrict the alkenes to approach the catalyst only from either side of the plane of the ligand.

Another structural evidence that explains its selectivity towards cis alkenes can be observed in the space-filling model of the catalyst (visualised using Jmol). The catalyst has a planar structure with a chlorine atom attached perpendicular to the plane. Although the mechanism of the epoxidation is subjected to controversy[6], a likely route involved exchange between the chlorine atom and oxygen atom from NaOCl to from the activated Mn=O catalyst, which then transfer the oxygen onto the alkene, forming the epoxide.

The planar structure of the catalyst therefore has a cis selectivity because the ligand would present a steric bulk to the approach of trans alkenes thereby making the double bond less accessible whereas the cis alkenes have substituents all on the same side of the double bond thus favouring the formation of the epoxide.

Another interesting feature worth noting would be that the tBu groups could also give rise to much higher selectivity as it might provide a steric bulk to the approach of alkene from the direction of the tBu groups, forcing the alkenes to approach via the opposite end of the plane. This feature is also best observed on the space-filling model of the catalyst.

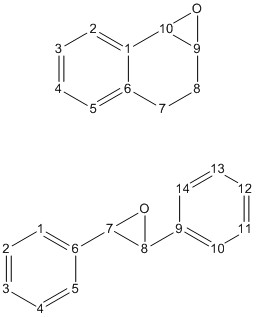

Analysis of NMR Data of Synthesised Epoxides

In the synthesis laboratory, 1,2-dihydronapthlene and trans-stilbene were subjected to epoxidation using both the Jacobsen's and Shi catalysts. This section aims to look at the computed[7][8] and literature values of various properties of the synthesised epoxides. NMR (both 1H and 13C) comparison were made. The structure of both epoxides were first optimised on Avogadro using the MMFF94s force field and then the NMR calculation were carried out on the optimised structures via HPC.

1H NMR Analysis

A comparison of the literature value with the computed value of the proton chemical shift of the two epoxides and the results were tabulated below.

| Computed δ in ppm |

Literature[9] δ in ppm |

Computed δ in ppm |

Literature[9] δ in ppm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.49 (1 H) | 7.33 (1 H) | 7.48 - 7.57 (10 H) | 7.30 - 7.38 (10 H) |

| 7.39 (2 H) | 7.14 - 7.21 (2 H) | 3.54 (2 H) | 3.87 (2 H) |

| 7.20 (1 H) | 7.01 (1 H) | ||

| 3.59 (2 H) | 3.65 - 3.78 (2 H) | ||

| 2.88 (1 H) | 2.65 - 2.70 (1 H) | ||

| 2.27 (1 H) | 2.45 (1 H) | ||

| 2.21 (1 H) | 2.31 - 2.39 (1 H) | ||

| 1.56 (1 H) | 1.60 - 1.70 (1 H) | ||

From the table it can be seen that the computed values and the literature values are very similar (± 0.2 ppm). An interesting general observation was that while the computed chemical shifts of protons within the aromatic rings were overestimated, the aliphatic proton chemical shifts were underestimated. With the similarity in the computed and literature chemical shift, it can be assumed that the conformation of the two epoxides were as shown in Table 6.

13C NMR Analysis

Following the same procedure for the analysis of the taxol intermediate 8 and 9, the graphs below (Figure 6) shows the difference (Literature - Predicted) between the literature and the predicted values for the chemical shift for both epoxides.

Figure 6: Difference between the computed and literature values of 13C NMR of epoxides

From the graphs it can be seen that most chemical shifts on either compounds have very comparable values (± 5 ppm). However carbon 4 on 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide and carbon 1 and 10 of stilbene oxide have a larger deviation from the literature. With reference to the environment these carbons are in however, do not show any presence of heavy atoms in its proximity and thus corrections due to presence of heavy atoms is not a valid reason for the anomalies. Despite computing the predicted 13C chemical shifts of many other possible conformers of the two epoxides, the computed values of other conformers showed larger deviations from the reported chemical shifts. Another interesting observation would be similar to what was observed in the 1H NMR analysis. The calculated chemical shifts of aromatic carbon were higher than literature whereas that of the aliphatic carbons are mostly lower than literature values.

Calculation of Optical Properties of Epoxides

Calculation of the optical properties would be useful in the determination of the stereo configuration of isomers. Three different methods can be used, of which two would be explored in this assignment - optical rotation at a specific wavelength and the Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD). The last method (Vibrational Circular Dichroism) cannot be used due to the lack of the required instrumentation.

Optical Rotation

The optical rotation for 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide[10] and stilbene oxide[11] were calculated and compared against literature value. Calculations were performed on previously optimised structures when calculating the predicted NMR chemical shifts via the HPC with the appropriate solvents according to literature (benzene for stilbene oxide and chloroform for 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide) and wavelength (589 nm). The results were tabulated in the table below.

| Computed (°) | Literature[12] (°) | Computed (°) | Literature[13] (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| - 155.79 | - 138 | + 304.76 | + 319.8 |

From the table it is shown that the computed optical rotation for 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide deviated slightly from the literature value. The sign of the rotary power correspond to the assignment of 1S,2R for 1,2-dihydronapthalene, which corresponded to the enantiomer used in the calculation. This could suggest that either the computed structure is the wrong conformer or the literature value is not accurate. Whilst the former could be a possibility, the latter could happen due to presence of 1R,2S enantiomer when the reading was made, or simply due to presence of impurities. Stilbene oxide however, is in closer agreement to the literature reported values. When comparing to literature, it corresponded to the assignment of R,R-stilbene oxide, which is in agreement with the enantiomer used to compute the value.

ECD Spectra

Whilst there are no literature comparison to be made for ECD spectra of the epoxides due to the lack of the appropriate chromophore, the computed spectra can be generated to observed the theoretical spectra produced. The calculations[14][15] were down on a previously optimised structure when computing the predicted NMR and visualised on GaussView.

Figure 7: ECD Spectra of 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide (top) and stilbene oxide (bottom)

Assigning the Absolute Configuration from the Transition State

The absolute configuration can be assigned by looking at the transition state of the reaction. For the epoxidation reaction of trans-β-methylstyrene using both the Jacobsen's and Shi catalyst, the calculations of free energies were obtained on various transition state based on the spatial arrangement of the two reactants. The lowest energy arrangement were chosen for both epoxidation reactions and the differences were taken to obtain the equilibrium constant, K using the formula ΔG = RT ln K, where the temperature was assumed to be at 298 K. The results is shown in the table below:

| Epoxidation using Shi Catalyst | Epoxidation using Jacobsen's Catalyst | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free energy ΔG (kJ/mol) |

- 3526131.9477[16] (R,R enantiomer) |

- 3526111.7287[17] (S,S enantiomer) |

-8882734.9568[18] (R,R enantiomer) |

-8882756.3205[19] (S,S enantiomer) |

| Free energy difference (kJ/mol) |

- 20.219 (ΔGRR - ΔGSS) |

- 21.364 (ΔGSS - ΔGRR) | ||

| Equilibrium Constant, K |

3501 | 5557 | ||

| Enantiomeric Excess | 99.97 % (R,R configuration) |

99.98 % (S,S configuration) | ||

Based on the calculations in the table above, it can be seen that the epoxidation of trans-β-methylstyrene by both catalysts were able to produce the epoxides with a high enantiomeric excess. Despite the trans configuration of the alkene, the epoxidation by Jacobsen's catalyst was able to produce 99.98 % enantiomeric excess of the desired product. The reaction for favourable epoxidation can be best explained in the later section on non-bonding interaction.

The enantiomeric excess of 99.97 % of the epoxidation by Shi catalyst was in close agreement with the observed literature value at 94 %.[3] The preferred R,R configuration over the S,S epoxide is also the same as reported. Analysis of the epoxidation by Jacobsen's catalyst is a little more complicated. The literature reported that the S,S configuration of the resultant epoxide has an enantiomeric excess of 20 %.[20] This epoxidation was carried out with the S,S enantiomer of a variant of the salen ligand. In comparison, the calculated enantiomeric excess was made with the R,R configuration of the salen ligand. This would correspond to 20 % enantiomeric excess of the R,R epoxide. This significantly deviates from the calculated value of 99.98 % enantiomeric excess of the S,S enantiomer. This has shown the limitations of computational calculation as it is not an accurate representative of the understanding of the asymmetrical properties of the Jacobsen's catalyst.

The literature value of the enantiomeric excess from the two reactions would be logical. The Shi catalyst has a higher selectivity for trans alkenes and thus generating epoxides with high enantiomeric excess (94 %).[3] The Jacobsen's catalyst however, favours cis alkene and thus would be more likely to give a lower enantiomeric excess (20 %)[20] of the the reaction with a trans alkene (ie. trans-β-methylstyrene). As discussed later below, the planar structure of trans-β-methylstyrene would still allow the epoxidation by Jacobsen's catalyst to proceed. However, it can epoxidise on either face of the double bond with equal probably thus leading to lower enantiomeric excess. The computed value therefore does not reflect accurately the enantiomeric excess of the reaction of trans-β-methylstyrene with the Jacobsen's catalyst.

Non-covalent Interaction (NCI) Analysis of Transition State

A NCI analysis can also be done on the transition state of the epoxidation reaction. The epoxidation of trans-β-methylstyrene by Jacobsen's catalyst[21] was subjected to the analysis. The non-covalent interactions were generated on GaussView and visualised by a Java applet online. The interaction is shown in Figure 8 below.

Orbital |

Figure 8: Transition state of the reaction between the activated Jacobsen's catalyst and trans-β-methylstyrene

From the above, a few observations can be made about the transition state. Firstly, there are very little unfavourable interaction between the two molecules. The colours of the interaction is largely green in colour, which indicate a mildly favourable interaction. A favourable interaction in the transition state would therefore indicate that the epoxidation of trans-β-methylstyrene by Jacobsen's catalyst would lead to a high possibility of formation of the epoxide. However it is interesting to note that the Jacobsen's catalyst preferentially epoxides cis alkene instead.[1] The favourable interaction of trans-β-methylstyrene can be best explained by looking at the geometry of the alkene. Due to the planar nature of the alkene, it is still able to approach the activated Jacobsen's catalyst such that the alkene bond is still accessible.

It is also interesting to note that a large portion of this interaction arises from the phenyl group on the ligand and on trans-β-methylstyrene. This favourable interaction is due to the π-π interaction between the two rings. Interactions between such systems are the basis of some of the observed phenomenon including the stacking of DNA and other large molecules.[22] There are three different interactions observed between two benzene rings - the sandwich, T-shaped and the parallel-displaced configuration.[22] From the diagram, it can be seen that the interaction shown corresponds to the parallel-displaced configuration.

It is worth noting that while red/yellow interactions indicate an unfavourable interaction and blue/green show favourable interaction, there are regions on the Jacobsen's catalyst showing a co-existence of both types of interaction. This can be observed between the tBu group substituent and the aromatic protons adjacent to it. The concurrent attractive/repulsive force is not one that would be observed in a formal bond.

Electronic Topology (QTAIM) Analysis of Transition State

The same transition state[21] can also be subjected to an electronic topology analysis. The electronic topology of the transition was visualised using Avogadro2. Those in yellow are the Bond Critical Point (BCP) and are observed between bonds. These BCP interactions can also be observed on weak interactions. Figure 9 shows the side profile of the transition state. The dotted line indication the weak interaction between the activated Jacobsen's catalyst and trans-β-methylstyrene. While this analysis is unable to tell us whether the interaction observed is a positive or negative one, this can be resolved by looking at the NCI analysis above. From Figure 8, it shows that the region for which there are mildly attractive interaction correspond well to the region of which the electronic topology analysis showed weak interaction. Therefore the interactions are positive.

Figure 9: Side profile of the electronic topology analyse of the transition state between the activated Jacobsen's catalyst and trans-β-methylstyrene

For the BCP indicated between covalent bonds, two observations can be made. For C-C bonds, the BCP lies in the centre of the bond. For heteroatom bonds such as C=N or C-H bonds, the BCP is found to be closer to one molecule. It is observed that the BCP is always found further away from the more electronegative atom. This is because BCP is defined to be the point of which the electron density is found to be zero.[23] As such, the more electronegative atom would have a larger electron density than that of the other molecule, hence resulting in the shift of the BCP towards the less electronegative atom. Figure 10 shows the various BCP along covalent bonds.

Figure 10: Illustration of various BCPs in the transition state

New Candidates for Investigation

The investigation of simple molecules can be made in the same way as the epoxides in this study. One epoxide that can be investigated is 2-(chloromethyl)oxirane as shown on the right. The S enantiomer has been reported to have an optical rotation of + 32.2 ° at 1.25 g/100 mL in methanol.[24]

Part 2 References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tian, H.; She, X.; Shu, L.; Yu, H.; Shi, Y. Highly Enantioselective Epoxidation of cis -Olefins by Chiral Dioxirane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11551–11552. DOI:10.1021/ja003049d Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "jacobsen is cis" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Tu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Y. An Efficient Asymmetric Epoxidation Method for trans -Olefins Mediated by a Fructose-Derived Ketone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 9806–9807. DOI:10.1021/ja962345g

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Wang, Z.; Tu, Y.; Frohn, M.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y. An Efficient Catalytic Asymmetric Epoxidation Method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 11224–11235. DOI:10.1021/ja972272g Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "shi is fructose" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Glockler, G. Carbon–Oxygen Bond Energies and Bond Distances. J. Phys. Chem. 1958, 62, 1049–1054. DOI:10.1021/j150567a006

- ↑ Rowland, R. S.; Taylor, R. Intermolecular Nonbonded Contact Distances in Organic Crystal Structures: Comparison with Distances Expected from van der Waals Radii. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 7384–7391. DOI:10.1021/jp953141%2B

- ↑ Linker, T. The Jacobsen–Katsuki Epoxidation and Its Controversial Mechanism. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. English 1997, 36, 2060–2062. DOI:10.1002/anie.199720601

- ↑ Soo, J. 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide NMR calculation. D-Space, 2014 DOI:10042/27512

- ↑ Soo, J. stilbene oxide NMR calculation. D-Space, 2014 DOI:10042/27514

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ji, L.; Wang, Y.-N.; Qian, C.; Chen, X.-Z. Nitrile-Promoted Alkene Epoxidation with Urea–Hydrogen Peroxide (UHP). Synth. Commun. 2013, 43, 2256–2264. DOI:10.1080/00397911.2012.699578 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "chem shift of epoxides" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Soo, J. 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide optical rotation. D-Space, 2014 DOI:10042/27511

- ↑ Soo, J. stilbene oxide optical rotation. D-Space, 2014 DOI:10042/27513

- ↑ Boyd, D. R.; Sharma, N. D.; Agarwal, R.; Kerley, N. a.; McMordie, R. A. S.; Smith, A.; Dalton, H.; Blacker, a. J.; Sheldrake, G. N. A new synthetic route to non-K and bay region arene oxide metabolites from cis-diols. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994, 1693. DOI:10.1039/C39940001693

- ↑ Wang, B.; Wu, X.; Wong, O. A.; Nettles, B.; Zhao, M.; Chen, D.; Shi, Y. A diacetate ketone-catalyzed asymmetric epoxidation of olefins. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 3986–9. DOI:10.1021/jo900330n

- ↑ Soo, J. 1,2-dihydronapthalene oxide ECD. D-Space, 2014 DOI:10042/27510

- ↑ Soo, J. stilbene oxide ECD. D-Space, 2014 DOI:10042/27509

- ↑ Rzepa, H. S. Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.738037

- ↑ Rzepa, H. S. Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.739117

- ↑ Rzepa, H. S. Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.856651

- ↑ Rzepa, H. S. Jacobsen trans methyl styrene 1 D-Space, 2013 DOI:10042/25945

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Zhang, W.; Loebach, J. L.; Wilson, S. R.; Jacobsen, E. N. Enantioselective epoxidation of unfunctionalized olefins catalyzed by salen manganese complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 2801–2803. DOI:10.1021/ja00163a052 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "jacobsen ee" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 21.0 21.1 Rzepa, H. S. Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3 figshare, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.856649

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Sinnokrot, M. O.; Valeev, E. F.; Sherrill, C. D. Estimates of the ab initio limit for pi-pi interactions: the benzene dimer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 10887–93. DOI:10.1021/ja025896h Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "benzene stacking" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Boyd, R. J.; Boyd, S. L. Group electronegativities from the bond critical point model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 1652–1655. DOI:10.1021/ja00031a018

- ↑ Sadhukhan, A.; Khan, N. H.; Roy, T.; Kureshy, R. I.; Abdi, S. H. R.; Bajaj, H. C. Asymmetric hydrolytic kinetic resolution with recyclable macrocyclic Co(III)-salen complexes: a practical strategy in the preparation of (R)-mexiletine and (S)-propranolol. Chemistry 2012, 18, 5256–60. DOI:10.1002/chem.201103574