Rep:Mod:jlorgwik

Introduction

The following is James Lees’ submission for the organic module of the computational chemistry lab course. The programmes used included ChemBio3D Ultra 12.0, ChemDraw Ultra 12.0, Gaussview 3.0, Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, EndNote X3. Gaussview 3.0 was used instead of Gaussview 5.0 as the 5.0 version was prone to crashing.

Modelling Using Molecular Mechanics

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

The 2 isomers of the cyclopentadiene dimer 1(exo) and 2(endo), and the isomers of the hydrogenated dimer (3 and 4) were all created in ChemBio3D. Using MM2 molecular mechanics the structures were then optimised providing the energy contributions including: stretching (str), bending (bnd), torsion (tor), van der Waals (vdw). A comparison of these energies allows a comparison of their relative energies.

The endo isomer(2) is produced specifically over the exo isomer(1) which means that 2 must be the more stable. This is indeed shown in the overall energy given for the molecules, 31.8817 Kcal.mol-1 compared with 34.0063Kcal.mol-1. The lower energy of the endo isomer is mainly accounted for by a lower degree of torsional strain: 7.64545 Kcal.mol-1 compared to 9.5146 Kcal.mol-1 in the exo form, thus accounting for 87.98% of the energy difference.

Torsion is so much higher in the exo isomer because bond angles in 1 are so much further from the ideal of 105 for an sp3 carbon. A simple observation of each molecule also appears to show that 1 has its rings further twisted out of proportion than is visible in 2 resulting in higher torsional strain.

A comparison of the energies of the potential hydrogenated products of 2 shows isomer 3 to posess a lower energy (29.256Kcal.mol-1) than isomer 4(34.9661 Kcal.mol-1). The largest discrepancy between the isomers in this case is that 4 has a far higher result for the bending energy (19.1509) compared to 3 (13.0418) meaning it is being considerably further bent from the ‘norm’. This results in 4 being the less stable isomer and the much less likely product of the hydrogenation.

Knowing this we can say the double bond on the right hand side of the diagram of molecule 2 is less likely to be attacked during hydrogenation resulting in a reaction that selectively produces isomer 3. Considering that it is stated in the project notes that molecule 2 is favoured over 1 almost entirely, and the difference in energy between 1 and 2 is less so than for 3 and 4, it is reasonable to assume 3 will be the predominant product and as it is the thermodynamically more stable product it can be concluded that the hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene dimer is thermodynamically controlled.

Note that although the energy value at the bottom of the results does not correspond to any particular thermodynamic property, a lower value still corresponds to a more thermodynamically stable compound as this energy is a sum of the distortions from the ideal.

| energy | molecule 1 /Kcal.mol-1 | molecule 2 /Kcal.mol-1 | molecule 3 /Kcal.mol-1 | molecule 4 /Kcal.mol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| str | 1.2515 | 1.2861 | 1.132 | 1.268 |

| ben | 20.8585 | 20.6031 | 13.0418 | 19.1509 |

| str ben | -0.8393 | -0.8418 | -0.5659 | -0.8404 |

| tor | 9.5146 | 7.6545 | 12.3966 | 11.0657 |

| non 1-4 vdw | -1.5614 | -1.4326 | -1.3152 | -1.6202 |

| 1-4vdw | 4.3327 | 4.2351 | 4.4256 | 5.7799 |

| dip-dip | 0.4497 | 0.3773 | 0.141 | 0.1623 |

| energy | 34.0063 | 31.8817 | 29.256 | 34.9661 |

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Addition to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

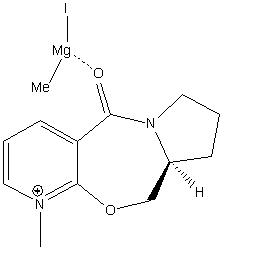

Two examples of stereochemistry of nucleophilic addition to a pyridinium ring were investigated: 5 being converted into 6 using MeMgI and 7 being converted to 8 upon reaction with PhNH2.

If the MeMgI component is put into the calculation an error message is observed stating that ‘WARNING! No atom type was assigned to the selected atom!’ with the selected atom being the Mg. This is because the MM2 method is unable to perform calculations with metals.

When a molecule of the Grignard reagent MeMgI comes close to molecule 5, the Mg is able to coordinate with the oxygen of the amide[1]. This results in strong region and stereo control as the δ- Me group is forced to attack the 4 position of the pyridinium ring rather than any other position of the ring.

|

According to the literature there are 2 possible conformations of 5: where the oxygen of the amide is above the plane of the pyridinium ring or simply in the plane. However the computational analysis only revealed the conformation where the oxygen was above the plane of the ring (slightly) after trying many different conformations before optimising the geometry. It was not found to be possible to find a conformational minima with the carbonyl below the plane of the ring. Therefore when the Mg coordinates the methyl group has to add above the plane of the ring resulting in the conformation of molecule 6.

|

Molecule 8 is formed into the given conformation due to dipolar coupling, as shown in the image below, between the H shown and the phenyl group[2] This attraction is seemingly strong enough to cause the incoming amine nucleophile to form into this conformation.

|

|

The analysis of this reaction did not take into account any MO effects at all meaning that potential stabilising or destabilising effects have been ignored. This said the method does explain the observed conformations reported in the literature, but if MO effects had been taken into account a more complete explanation may be made.

References

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol.

When either molecule 10 or 11 as I had initially drawn them were put through the minimising energy calculation of MM2 the molecule changed to the form shown in 11 with the carbonyl pointing down in respect to the page. Upon manual manipulation in ChemBio3D of the position of the carbonyl group the desired geometry of molecule 10 was achieved, immediately it was noted that it possessed a higher final energy (59.7897 kcal/mol) compared to 44.3248 kcal/mol for molecule 11, with this greater degree of stability in 11 being due largely to a difference in the bending energy. This means that to have the carbonyl group pointing up destabilises the molecule by forcing the molecule to be more bent.

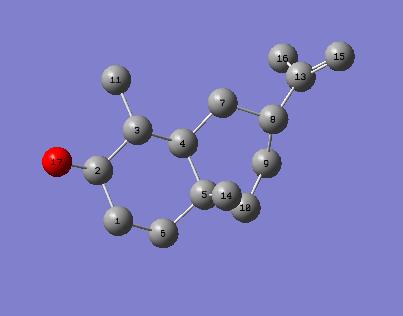

A hyper-stable alkene is a compound where an alkene which is part of a cyclic system serves to reduce the overall strain energy of the compound.[1] Ordinarily having an alkene in a ring increases the strain energy of the compound but in a hyperstable alkene the strain energy is lowered which can be demonstrated using the heats of hydrogenation.[2]

As such, if the molecule undergoes a functional group conversion at the alkene it can be expected to proceed slowly as the alkene being in the ring has effectively stabilised the molecule making a conversion likely to be thermodynamically unfavourable.

References

Modelling using Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital theory

Regioselective Addition of dichlorocarbene

|

|

|

|

|

|

The HOMO shows that the Cl-Cσ* orbital lies anti peri-planar to the exo π orbital which is occupied. This provides a stabilising effect for the exo double bond which in turn makes the endo alkene more nucleophilic in an electrostatic sense and a frontier orbital sense. [1]

Both molecules 12 and 12H were subjected to optimisation and frequency calculation using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) submitted through SCAN. The resulting .fchk files were put into Gaussview 3.0 and their vibrational frequencies inspected.

|

The observed frequency of the C=C double bonds stretches in 12 are observed at 3176cm-1 and 3178cm-1. The C-Cl stretch is observed at 770.8cm-1.

|

|

|

In the hydrogenated version of 12 with only 1 double bond, labelled 12H, the C=C double bond stretch is observed at 1736cm-1 and the C-Cl stretch is observed at 551cm-1

|

|

The absence of the 2nd double bond in 12H has had some profound effects on the observed stretching frequencies. Firstly the C=C stretching frequencies in 12 are at much higher wave numbers (3176,3178cm-1) compared to 12H (1736cm-1). Ordinarily stretching for C=C double bonds at values around 3170cm-1 indicates a conjugated system whereas 1736 would be an isolated double bond. The system is not conjugated so this must be explained through the presence of the chlorine syn to the double bond providing stability via the anti periplanar interactions of the Cl-Cσ* orbital and the exo π orbital.

The C-Cl stretch is also observed at a lower wavenumber in 12H than in 12. Which is a result of the presence of the extra C=C double bond.

References

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese, H. Rzepa, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 1992, 447 - 448, DOI: 10.1039/P29920000447

Mini Project- Stereoselective dissolving metal reduction

A recent paper [1] described the reduction of the carbonyl of molecule 13 into the alcohol of 14 with complete stereoselectivity. In the following project I will discuss how it could be determined that the reaction had come to completion, how the stereoisomerism could be determined, why the particular stereoisomer was created, whether the 13C NMR and related 3JH-H couplings match those stated in the literature and whether the optical rotation matches that given in the literature.

|

Reaction Completion

The reaction converting 13 into 14 requires the reduction of the ketone in 13 into the alcohol of 14 using the mechanism of dissolved metals (Li in NH3 in this case) to reduce the functional group. A very high yield of 92% is recorded in the paper.

The reaction can be said to be complete when the IR spectrum shows no signs of a carbonyl band which would indicate the presence of molecule 13. An IR stretch for an alcohol group would also show the presence of 14, but if there is still a carbonyl stretch then it would not answer whether the reaction had gone to completion. NMR might also be used to indicate the presence of the protons not present in 13 (the alcohol and the proton on the carbon of the alcohol). Though again these would merely show the existence of 14, not prove the reaction had gone to completion.

Therefore to determine whether the reaction has gone to completion the IR spectrum would be investigated. The paper does not give the experimental IR spectra, so instead the peaks of interest will be discussed using the computational spectra to illustrate how the end point of the reaction could reliably be concluded.

|

As would be expected the analysis shows that for molecule 13 there is a significant peak of intensity at 1806cm-1 corresponding to a stretching vibration in the carbonyl group. This is not present in the IR of molecule 14, so an absence of this in the spectra of the product that has been synthesised would indicate the reaction has gone to completion.

Determining and Predicting the Stereochemistry

Molecule 14 is potentially 1 of 2 optical isomers, though only 1 is created in the synthesis laid out in the literature. The 2 possible enantiomers are shown below as 14 and 14* where 14 is the product said to be formed in the synthesis.

|

Isomer 14 is the R enantiomer whilst 14* is the S enantiomer following from the CIP system[2] . As such enantiomer 14 will bend polarised light to the right and 14* would bend polarised light to the left allowing the exact conformation to be deduced. This information was gathered experimentally and presented in the literature and the value of -11.6 for [α]D20 thus confirming that the molecule is in the form shown in molecule 14.

The optical rotation was calculated returning an answer of 174.44˚ for molecule 14, which can be converted to -5.56˚ though this is still far from the experimental value. However as the job took 1 day 3 hours 38 minutes 2.7 seconds of CPU time I concluded that it was not worth ‘playing’ with the configuration of the molecule to get a closer match as it suggests in the script. This would merely tie up the queue and waste the computers, others in the queue and my time.

Similarly the result of [α]D20 for molecule 13 was -19.5˚ in the literature and 169.26˚ (-10.74˚) from the calculation. Again the result was far off but with a CPU time of 23 hours 13 minutes 6.1 seconds the same conclusion was reached with regards to repeating with a different conformation.

However the fact remains that the way in which the stereochemistry can be confirmed is through investigation of the optical rotational properties of the molecule. The experimental result from the literature confirms the molecule is as shown in 14. It can also be concluded that using a computational analysis for predicting optical rotation is not yet at a stage where the accuracy is high nor where the calculation is quick.

The synthesis proceeds with complete control of stereochemistry making an investigation into why such control is achieved worthwhile.

It can be seen upon a glance inspection that the OH group in the position shown in 14 might provide less steric hindrance than in 14* as there is a methyl group on the adjacent carbon to the alcohol which is in the same direction, and by minimising the steric hindrance here the energy of the system will be lowered.

This would be shown quantitatively in the IR output file where the sum of electric and thermal energies is given. The energy is in Hartrees allowing for an easy comparison of the free energies of the molecules: -662.159136 for 14 and -662.158468 for 14*. Which being extremely similar means the answer must not lie with 1 molecule being inherently lower in energy.

Running the MM2 geometry optimisation on molecules 14 and 14* and comparing the energy values also shows that 14 is going to be the ever so slightly favourable molecule. 14 exhibits less variation from the ideal in bending (3.65 to 3.85Kcal.mol-1) and torsion (10.91 to 11.15Kcal.mol-1).

However these differences are really quite small, meaning that the vast favourability of 14 over 14* is unlikely to be purely thermodynamically controlled meaning that the reaction must be somewhat kinetically controlled with the answer lying in the mechanism.

The reaction proceeds as follows[3]:

|

The addition of the H+ to the ketyl ,[4] [5] occurs through axial protonation of the ketyl. The axis on which the protonation is determined by the best overlap between the incoming H+ ions orbital and the ketyl LUMO orbital. If the attack is made from ‘above’ the ring as drawn this overlap is less obstructed as shown in the diagram below of the ketyl LUMO.

|

Comparison of 13C NMR from literature and computational analysis

13C NMR spectra were calculated for molecules 13 and 14 using the molecules which had been optimised for their geometry at the mpw1pw91/6-31(d,p) by creating a Gaussian input files altered to perform NMR calculations. These were submitted to the SCAN and the data then analysed in Gaussview 3.0. The purpose was to determine whether the structures put forth in the literature match those predicted analytically by comparison of the NMR spectra.

The literature reports the 13C NMR of compound 13 as: 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 213.25 (C-3, s), 146.28 (C-11, s), 111.06 (C-13, t), 45.66 (C-5, d), 45.24 (C-4, d), 41.74 (C-1, t), 38.32 (C-7, d), 38.20 (C-2, t), 36.32 (C-9, t), 33.99 (C-10, s), 27.54 (C-6, t), 23.02 (C-8, t), 22.71 (C-12, q), 16.10 (C-15, q), 11.18 (C-14, q). The computationally predicted spectra [6] is:13C NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm): 207.82 (C-2), 147.02 (C-12), 109.80 (C-14), 47.85 (C-3), 45.55 (C-4), 43.2 (C-6), 41.58 (C-8), 38.99 (C-1), 38.38 (C-10), 33.22 (C-5), 31.90 (C-7), 26.03 (C-9), 23.32 (C-13), 18.61 (C-15), 13.69 (C-11).

The computational analysis supplies no data on the coupling of the carbon nuclei so no singlet, doublet etc assignments can be made. The paper has labelled the carbons in a different manner to how Gaussview has them, and as such to compare the data it was necessary to decipher the common carbons. This was done by putting the NMR chemical shift values along with their carbon number into a table in Excel. The data was then sorted such that the chemical shift values were put into a descending order whilst keeping the carbon label. This allowed for the data from the reference and from the computational analysis to be seen side by side.

The data matched very well with an average difference between the reference and calculated chemical shifts of just 2.09ppm; the average being calculated by summing the modulus of the differences and dividing by the number of carbons. It can thus be concluded that the data reported in the literature and the values calculated give good agreement on the structure of compound 13 though the labelling is different in the reference.

| Carbon # | ref δ/ppm | Carbon # | calc δ/ppm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 147.11 | 12 | 147.43 |

| 13 | 110.67 | 14 | 109.28 |

| 3 | 76.86 | 2 | 74.26 |

| 5 | 43.22 | 3 | 42.32 |

| 1 | 39.93 | 4 | 41.726 |

| 7 | 39.19 | 6 | 41.46 |

| 4 | 38.88 | 4 | 41.22 |

| 9 | 37.10 | 10 | 39.05 |

| 10 | 33.78 | 5 | 33.50 |

| 2 | 30.92 | 7 | 30.87 |

| 6 | 26.05 | 1 | 30.60 |

| 8 | 23.08 | 9 | 26.06 |

| 15 | 16.68 | 15 | 18.76 |

| 14 | 14.87 | 11 | 15.39 |

The 13C NMR from the reference for molecule 14 is as follows: 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 147.11 (C-11, s), 110.67 (C-13, t), 76.86 (C-3, d), 43.22 (C-5, d), 39.93 (C-1, t), 39.19 (C-7, d), 38.88 (C-4, d), 37.10 (C-9, t), 33.78 (C-10, s), 30.92 (C-2, t), 26.05 (C-6, t), 23.08 (C-8, t), 22.82 (C-12, q), 16.68 (C-15, q), 14.87 (C-14, q). The computationally predicted spectra [7] is:13C NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm): 147.43 (C-12), 109.28 (C-14), 74.26 (C-2), 42.32 (C-3), 41.73 (C-1), 41.46 (C-6), 41.22 (C-4), 39.05 (C-10), 33.50 (C-5), 30.87 (C-7), 30.61 (C-1), 26.06 (C-9), 24.14 (C-13), 18.76 (C-15), 15.39 (C-11).

Again the labelling was different between the reference and the computational analysis, so the same method was employed to allow for the correct comparisons to be made. This time the data was an even closer fit with a mean difference of just 1.69ppm between the 2 values. Once more it could be concluded that the structure reported in the paper is the same as that predicted using the computational analysis.

| Carbon # | ref δ/ppm | Carbon # | calc δ/ppm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 213.25 | 2 | 207.82 |

| 11 | 146.28 | 12 | 147.02 |

| 13 | 111.06 | 14 | 109.80 |

| 5 | 45.66 | 3 | 47.85 |

| 4 | 45.24 | 4 | 45.55 |

| 1 | 41.74 | 6 | 43.2 |

| 7 | 37.32 | 8 | 41.58 |

| 2 | 38.20 | 1 | 38.99 |

| 9 | 36.32 | 10 | 38.38 |

| 10 | 33.99 | 5 | 33.22 |

| 6 | 27.54 | 7 | 31.90 |

| 8 | 23.02 | 9 | 26.03 |

| 12 | 22.71 | 13 | 23.32 |

| 15 | 16.1 | 15 | 18.61 |

References

- ↑ 1. L. Castellanos, C. Duque, J. Rodríguez and C. Jiménez, Tetrahedron, 2007, 63, 1544-1552.

- ↑ 1. L. Castellanos, C. Duque, J. Rodríguez and C. Jiménez, Tetrahedron, 2007, 63, 1544-1552.

- ↑ 1. G. Stork and S. D. Darling, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2002, 86, 1761-1768

- ↑ Some modern methods of organic synthesis, W. Carruthers, pg 443, 1986

- ↑ IUPAC

- ↑ Predicted NMR of molecule 13 DOI:10042/to-2530

- ↑ Predicted NMR spectrum of molecule 14 DOI:10042/to-2531