Rep:Mod:jlinorgwik

The inorganic module for James Lees' 3rd year computer lab.

Borane and Trichloroborane

In this section of the report the molecules BH3 and BCl3 were optimised and then analysed using the MOs, NBO analysis and vibrational analysis.

Borane

Optimisation

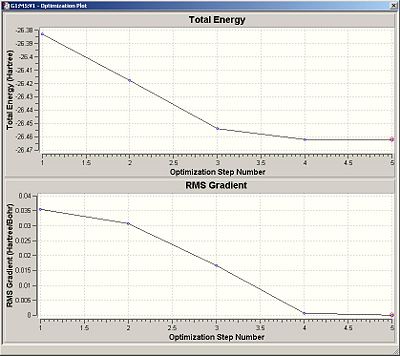

First the molecule was optimised using the DFT B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set, a very simple level of theory used to get an initial optimisation of the molecule so that for more complex calculations the molecule’s geometry is already some of the way towards optimisation allowing for faster calculations.

The optimised bond length for BH3 was 1.19Angstroms and the bond angle was 120degrees as would be expected. The file type of the molecule output summary was a .log. The calculation type is FOPT. The calculation method is RB3LYP. The basis set is 3-21G. The final energy is -26.4622a.u. The gradient is 0.00000285a.u. The dipole moment is 0.000 Debye. The point group is D3H.

Optimisation is complete as the gradient is significantly less than 0.1 and the output file shows the calculation has converged. Below is the optimisation plot.

|

Molecular Orbitals

The molecular orbitals of BH3 [1] were calculated and then visualised on Gaussview. It was observed that unoccupied MOs were more diffuse than occupied MOs (e.g 6 is diffuse and an unusual form).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Natural Bond Orders

|

|

From the output file it was seen that the B-H bonds are of sp3 character as it is reported they consist of 33.3% s character and 66.7% p character from the boron and 100% s character from the H. There is also a formally occupied lone pair (indicated by LP*) on the boron which is 100% s character.

Molecular Orbitals

| vibration number | form of the vibration | Frequency | intensity | Symmetry D3h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

1145 | 93 | A" |

| 2 |  |

1205 | 12 | E' |

| 3 |  |

1205 | 12 | E' |

| 4 |  |

2593 | 0 | A1 |

| 5 |  |

2731 | 104 | E' |

| 6 |  |

2731 | 104 | E' |

|

Not all vibrations are visible in the spectrum as only the spectra which produce a dipole moment will appear in the vibrational spectra. Also several vibrations are so close to each other that they cannot be identified, for example vibrations 5 and 6 are both at 2731 making them indistinguishable; this being due to them being degenerate and part of the same pair of E’ vibrations. The same reasons are why vibrations 2 and 3 are indistinguishable leaving only 1 peak. Vibration 4 is not observed as it is totally symmetric and thus doesn’t result in a change in dipole moment meaning it is not an IR active vibration.

So in conclusion the only peaks that would be expected in the IR spectrum are those due to vibration 1 as it is asymmetric, vibration 2 and 3 joined together and vibrations 5 and 6 joined together, this is indeed what is observed by the 3 peaks in the IR spectrum.

Trichloroborane

The molecule was first optimised using Ground state DFT B3LYP/LANL2MB level of theory. The optimised BCl3 bond length was 1.87Angstroms and the angle was 120 degrees. The calculation was deemed a success as the output file showed it had converged and the RMS gradient was significantly below 0.001. Later the vibrational analysis confirmed this by yielding no negative vibrational frequencies. The summary file shows this information:

|

The same method and basis set must be used for both calculations to make any comparisons legitimate. Different levels of theory will yield different optimised geometries, although the differences are unlikely to be radical, with a higher level of theory giving an answer closer to the ‘true’ answer.

A frequency analysis is required so as to make certain that the optimised geometry is in fact the minimum of the curve. When the molecule is optimised the calculation changes factors until it finds a standing point in the potential energy curve, effectively calculating the first derivative. This doesn’t tell us if the point is a minimum, maximum or even a point of inflexion. As such to determine if the first standing point found is indeed a minimum the 2nd derivative of the potential energy curve is required, and this is found using the frequency analysis. A maximum in the curve would indicate that the structure is a transition state, whereas the minimum is the optimised geometry for the structure in question.

As such a frequency analysis was carried out using the same method and basis set. The resulting output file returned with the same overall energy as the optimisation output file confirming the successful calculation.

| vibration number | form of vibration | frequency | intensity | D3h point group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

213 | 4 | E' |

| 2 |  |

214 | 4 | E' |

| 3 |  |

376 | 44 | A2 |

| 4 |  |

413 | 0 | A1 |

| 5 |  |

939 | 259 | E' |

| 6 |  |

939 | 259 | E' |

|

The form of the vibrations observed is the same as for BH3 as would be expected, with again only 3 observed peaks in the IR spectrum which is again for the same reasons as explained in the BH3 section.

Literature values for the B-Cl bond lengths are 1.75A and the bond angle is 120 [2] compared to the calculated values of 1.87A and 120degrees. It is possible that at the level of theory applied in the calculations has not adequately accounted for hyperconjugation which would shorten the bonds.

Gaussview does not always show bonds when they might be expected because the distances between the atoms when calculated exceed a pre given limit in gaussview for the length of bonds between those 2 atoms. This does not in any way imply there are no bonds, something which is important in my mini project on metallocenes.

A bond is, in the covalent sense at least, a sharing of electrons between atoms. As such I would define a bond as being when 2 (or more) atoms atomic orbitals overlap to form a bonding molecular orbital which is at least partially filled.

I would expect the ground state structure of BCl3 to conform to a D3h symmetry as it is a trigonal planar molecule. This is what is observed from the calculation, though that was inevitable as it was constrained to fit the D3h point group with a very tight fit.

The optimisation of geometry took 13 seconds. The frequency analysis took 12 seconds.

- ↑ BH3 molecular orbitals DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2665

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997), Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.), Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, ISBN 0-7506-3365-4

Cis and Trans Isomerism in Octahedral Transition Metal Complexes

Optimisation

Both isomers were initially optimised using the BL3YP method and the pseudo potential LANL2MB. In addition loose convergence criteria were given. The structure that came back are linked below.

Cis optimisation 1- http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2585

Trans optimisation 1 http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-258

|

Both isomers were then corrected by modifying the dihedral angles to ensure the correct minimum had been reached for the given structure as described in the script.

|

The resulting output files were then used to produce a modified input to include d orbitals by putting in:

opt b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity

int=ultrafine scf=conver=9 extrabasis

at the start of the input file as described in the instructions, with the following at the end of the script:

(blank line)

P 0

D 1 1.0

0.55 0.100D+01

(blank line)

The geometries are posted below.

Cis optimisation 2(dihedrals set): http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2593

Trans optimisation 2(dihedrals set): http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2591

Cis optimisation 3(d AOs): http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2597

Trans optimisation 3 (dAOs): http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2595

Frequency Analysis

Upon frequency analysis of the optimised structures which included the d atomic orbitals it was observed that there were several negative frequencies in the region of -100Hz, so it was deemed that the optimisation had failed for these. My close inspection of the input and output files of both molecules optimisation and frequency calculations didn’t yield any reasons why this should be.

However if the geometry optimised to the point of having the dihedrals set, but no d atomic orbitals included then the frequency analysis gave no negative frequencies. For this reason these results were used for the subsequent discussion.

Cis Frequency: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2599

Trans Frequency: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2598

| Bond Type | Bond Length/A |

|---|---|

| Mo-C (carbonyls trans to carbonyls) | 2.06 |

| Mo-C (carnonyls trans to PCl3) | 2.01 |

| M-P | 2.51 |

| P-Cl | 2.24 |

| Bond type | Bond length/A |

|---|---|

| Mo-C(not in plane of Mo-P) | 2.06 |

| Mo-C (in plane of Mo-P) | 2.06 |

| M-P | 2.44 |

| P-Cl | 2.24 |

M-C bonds should be in area of 1.99A[1]. So this is in good agreement with my results. Mo-P should be around 2.57-2.62A[2], this time my bond lengths are slightly too short though not massively so especially in the cis isomer, though this is likely due to these bond lengths being from non octahedral complexes involving cp ligands. P-Cl bonds should be in the area of 2.14A[3], though this value is for trigonal bipyramidal PCl5 which accounts for the difference between my calculated values and the reference value.

| Cis | Trans |

|---|---|

| -623.5760a.u. | -623.5770.u. |

As the 2 molecules are isomers a valid comparison of their energies can be made owing to having the same number and type of atoms. There is an energy difference of 0.00104a.u. or 2.73052kJ.mol-1. This energy difference is actually less than the likely range of error of 10kJ.mol-1 meaning the potential for error is actually almost 4 times larger than the given difference in energy. This means that a) the energy difference is small and b) any discussion of which molecule has higher energy from the calculated results is more or less invalid.

That said it would be expected that the trans isomer would be of lower energy. This was also observed in 2nd year synthesis lab when the complexes were made, as the cis isomer converted to the trans isomer upon heating indicating a greater activation energy was required to form this, but a lower final energy of the compound. It has also been confirmed in the literature.[4]

The simplest reason for this is a steric consideration. The PCl3 ligands are fairly bulky and by putting them at opposite ends of the molecule steric hindrance is minimised. Also the carbonyl ligands will serve to pull electron density from the ligand they are trans to. In the trans isomer all carbonyl ligands are trans to other carbonyl ligands, whilst in the cis isomer some are trans to the PCl ligands. This will cause the Mo-P bond to weaken making the compound less stable as electron density has been taken from the bond, most likely the back bonding electrons from the metal to the P. This can be seen in the shorter bond lengths of Mo-P in the trans isomer, and as drawing that extra electron density from the Mo-P bond will strengthen the Mo-C bonds it can also be seen that the Mo-C bonds are shorter in the cis isomer as would be expected.

By altering the size of the PX3 ligands, for example changing the Chlorines to a very bulky group would make it even less sterically favourable for the molecule to take on the cis isomer form. By using a group which is small and acting as an electron donating group towards the phosphorous would make the cis isomer more preferable, an example would be using PEt3.

|

|

In trans only 1 CO stretching band is observed (at 1951cm-1), a result of a E’ vibration. Whereas in the cis isomer 4 bands are observed (at 1945, 1948, 1958 and 2023cm-1) due to two A1, a B1 and a B2 vibration. The difference here is that the trans isomer has D4h symmetry whilst the cis isomer has C2v symmetry which is a lower level of symmetry. The result is that although both molecules have the same number of CO vibrations there is only 1 which causes a change in the overall dipole moment of the trans isomer, while 4 have this effect in the cis isomer.[5] This is as would be expected from symmetry considerations. Note that even the A1 stretches are observed in the cis isomer due to the uneven distribution of the ligands.

The reference 1 lists IR stretches for the cis isomer as 1986, 2004, 2004, and 2072cm-1, and 1896cm-1 for the trans isomer. There is a significant degree of disagreement between these experimental values and the values which I have calculated, though they are all in the acceptable range for carbonyl stretches. The difference is most likely due to the level of theory to which the calculations were made.

A vibration at a very low frequency at room temperature can be interpreted as the motions of the centre of mass of the molecule as mentioned in the instructions in the frequency analysis for the first section of the report. These movements will be a result of the other vibrations moving the centre of mass, not true vibrations in themselves.

|

Mini Project On Metallocenes

In this mini project I seek to compare different sandwich complexes using a variety of energetic and electronic factors to analyse trends in areas such as stability.

The first group of molecules to be investigated will be metallocenes with different transition metals. Metallocenes are sandwich complexes where a transition metal ion has 2 cyclopentadienyl ligands bound to it in an η5 manner. The first and most often discussed (at least at an undergrad level) being ferrocene, the metallocene with a Fe2+ ion.

The first comparison will be between the metallocenes of chromium (chromocene), iron (ferrocene), cobalt (cobaltocene) and ruthenium (ruthenocene).

All molecules to be used are illustrated and labelled below.

|

The final optimised structures are linked below: 1- http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2738 2- http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2737 3- http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2745 4- http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2736 5- http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2742 6- http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2733 7- http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-2740

Pure Metallocenes

In this section the pure metallocenes shall be compared. Strictly a metallocene is "Organometallic coordination compounds in which one atom of a transition metal such as iron, ruthenium or osmium is bonded to and only to the face of two cyclopentadienyl [η5-(C5H5)] ligands which lie in parallel planes. The term should not be used for analogues having rings other than cyclopentadienyl as ligands."[6]. In this section the metallocenes cobaltocene, ferrocene, chromocene and ruthenocene shall be looked at.

Optimising the structure

All of the molecules were first optimised to a BL3YP/3-21G level to get a relatively fast initial optimisation allowing for a time/accuracy analysis and with the hope of optimising further from here.

Various optimisations didn’t give reasonable results. Fe and Ru came back sort of fine leaving me with the belief that others had failed due to no spin corrections being made. All of the molecules removed the dummy upon optimisation and Fe came back with 3 bonds from the cp ring to the central ion which seemed odd for an η5 ligand, though bonds shown in gaussview are not a true depiction of the bonding reality as discussed earlier in the report.

Several of the calculations took over an hour even at this level of theory, and all came back with the rings in an eclipsed formation, other than Ru, which came back staggered which would be expected as the shape and the calculation took a mere 3 minutes.

The molecules were then optimised again to a greater level of theory. The run time on jobs was anywhere between 5 minutes and 2 hours, so if the level of theory were to be equal between all molecules (allowing for a more valid comparison of molecules) a decent, but not massively high level of theory could be used. Therefore I decided that the molecules should be optimised to the B3LYP and 6-31G(d) level as this is said to be a good level to reach.

The molecules now being optimised with confirmation from the frequency analysis, which will be discussed in more detail later, were ready to be compared.

Analysis of structure

The first thing I looked at to compare was the distance between the 2 cp rings, which has been compiled into a table below:

| Metallocene | Cp ring seperation/A |

|---|---|

| chromocene | 3.43461 |

| ferrocene | 3.36522 |

| cobaltocene | 3.56936 |

| ruthenocene | 3.83972 |

As would be expected the seperation between the cp rings is sizeably larger for ruthenocene than the others. This is due to ruthenium being in a lower period and hence being of a larger size, the central ion is interacting via 4d rather than 3d atomic orbitals. Chromocene has a larger cp seperation than ferrocene as a consequence of it’s electronic structure.

Chromocene is a 16 electron compound whereas ferrocene is an 18 electron complex. 18 electron complexes are the most stable for transition metal complexes as in this way all the bonding and non-bonding Mos are filled (a1g, t1u, eg, t2g in an octahedral complex). In a 16 electron configuration the d orbitals are not filled resulting in the bonding not being as strong, causing weaker bonds and as a result greater seperation.

Cobaltocene is a 19 electron compound. Here there is an unpaired electron in an antibonding MO, making the bond signifantly weaker than in ferrocene causing a longer cp ring seperation. This seperation is greater than in chromocene, as here the bonding to the central ion is being weakened through antibonding rather than simply not being as strong as possible as in the case of chromocene.

The same trend is naturally also observed if the direct distance is found between the metal ion and the carbons on the cp rings.

| Metallocene | Distance/A |

|---|---|

| chromocene | 2.11 |

| ferrocene | 2.08 |

| cobaltocene | 2.14 |

| ruthenocene | 2.25 |

These are all in a reasonable range for the literature reported geometries e.g. Ferrocene C-M distance of 2.05A.[7] When the rings are staggered they are in a D5d point group, when eclipsed they are in the D5h point group. In the solid state they will exist in the eclipsed form. This will be further elaborated on in the MO analysis below.

When the molecules are not in the solid state the rings are free to rotate which is a result of there being no formal bonds between the metal and the cp rings. The bonding is from the delocalised π electrons on the cp rings combining with the d electrons and atomic orbitals on the metals. The freedom to rotate has been confirmed by both NMR[8] and STM[9].

Vibrational Analysis

The calculated IR spectra are shown below:

|

|

|

|

All of the spectra are very similar, as would be expected from only changing the central metal ion. It is worth noting that there is only 1 C-H stretch in each spectrum, this being at around 1131cm-1 (the value in Ferrocene), a result of all the C-H bonds being equivalent as they are in an aromatic system.

Below are the vibrations of the 7 vibrations with greatest intensity:

| vibration number | form of vibration | frequency | intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

456 | 18 |

| 2 |  |

480 | 18 |

| 3 |  |

836 | 17 |

| 4 |  |

1038 | 23 |

| 5 |  |

1131 | 20 |

| 6 |  |

1461 | 3 |

| 7 |  |

3289.78 | 15 |

MO analysis

The HOMO and LUMO of each metallocene are shown below.

| Metallocene | HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|---|

| chromocene |  |

|

| ferrocene |  |

|

| cobaltocene |  |

|

| ruthenocene |  |

|

The MOs are a combination of the d atomic orbitals on the metal and the delocalised π orbitals on the cp rings. The π orbitals are a combination of the pz orbitals from the carbons, and as a result not all combinations are entirely bonding in the ring as shown in the diagram below.

|

With this information it becomes possible to interpret the MO diagram below [10].

|

The MOs in the box are of the most interest for comparing the metallocenes. Firstly none are strongly bonding or anti bonding which allows for the variety of number of d electrons observed in metallocenes.[11]

The a1 orbital from the cp ligands, which is the lowest in energy, has no favorable overlap with the d atomic orbitals from the central metal. There is also very little interaction with the dz2 because the p-orbitals from cp lie on the dz2 nodal plane. The pair of degenerate e1g orbitals overlap quite well with the dxz and dyz orbitals on the metal creating π bonds. The metal dx2-y2 and dxy do overlap with the e2g orbitals on the ligand, although the degree of overlap is not large enough to create any real degree of bonding, leaving them effectively non bonding.

This model of bonding can be seen in the calculated MOs. For example in chromocene the HOMO has contributions from the e1 type orbitals on the cp rings, with the LUMO including the other in the pair of e1 orbitals. Both the HOMO and LUMO are overall anti bonding in this case, though the existence of the structure can be explained by looking at the HOMO-1 and HOMO-2.

|

|

Both of these are shown to be strongly bonding by the large degree of orbitl overlap. This again demonstrates that the orbitals which are boxed in the MO diagram are not strongly bonding or antibonding and it is the orbitals below this that allow for the structure to be held together. The boxed MOs are effectively non bonding in all the molecules, though the small differences here are the source of a large part of the differences between the molecules such as the cp ring seperation mentioned previously.

It is also seen that the MOs of ferrocene and ruthenocene are of the same form, as would be expected with them both being in the same group. Another point worth noting is that a large degree of the bonding character of the complex comes from the 2 cp rings MOs overlapping. When in an eclipsed formation this overlap is maximised as the carbons are eclipsed allowing for their pz orbitals to be closer. This is why the staggered formation is energetically preferred resulting in the complexes optimising into this structure. However at room temperature the rings are free to rotate as the electrons are in fact delocalised as the cp rings are aromatic, and this means it is not necessary for the carbons to be eclisped for an interaction to occur.

References

- ↑ doi|10.1016/0022-328X(95)2905873-6

- ↑ Doi:10.1002/zaac.200300413

- ↑ http://www.up.ac.za/academic/chem/mol_geom/trigbip.htm

- ↑ D.J Darensbourg, Inorg. Chem., 1979, 18, 1257

- ↑ Advanced Structural Inorganic Chemistry,W. Li, G. Zhou, T. Mak, pg249, OUP 2008, ISBN: 0199216940, 9780199216949

- ↑ IUPAC

- ↑ F.G. Stone, Advances in Organometallic Chemistry, Volume 40, 1996, Pg 136, ISBN: 0120311402, 9780120311408

- ↑ E. W. Abel, N. J. Long, K. G. Orrell, A. G. Osborne, V. Sik, J. Organometallic Chem. 403, 1991, 195–208. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(91)83100-I.

- ↑ L. Ah Qune, K. Tamada, M. Hara, eJ. surface Science and Nanotechnology, 6, 2008, 119-123 doi:10.1380/ejssnt.2008.119

- ↑ http://www.ilpi.com/organomet/cp.html

- ↑ Metallocenes: an Introduction, N.J Long, 1998, ISBN: 0632041625