Rep:Mod:jjb215ts

Introduction

Potential energy surfaces

A molecule with N atoms has 3N degrees of freedom, with three translational and three rotational degrees (for a non-linear molecule) of freedom. However, translation and rotation do not change the potential energy of a molecule (as the inter-nuclear distances do not change), so the potential energy of a non-linear molecule is a function of 3N-6 degrees of freedom or coordinates.[1] A plot of the potential energy as a function of these coordinates is called a potential energy surface (PES).[1]

A potential energy surface contains stationary points and these are points on the PES at which the first derivative of the potential energy is equal to zero (ie. gradient is zero) with respect to every degree of freedom. A minimum and a transition state (TS) are both stationary points on the PES, where a minimum corresponds to a stable configuration of a molecule and a transition state is a maximum along the minimum-energy path (reaction coordinate), which connects two minima.[1] A minimum is a point at which any movement in any degree of freedom will increase the potential energy. Whereas, at a transition state, movement along the reaction coordinate will decrease the potential energy but movement in any other degree of freedom will increase the potential energy.

A minimum and a transition state can be distinguished by considering the second derivative of the potential energy or curvature (force constants) with respect to every degree of freedom. A minimum is identified as a point at which the curvature is positive in every degree of freedom. Whereas, a transition state is a point at which the curvature is negative in only one degree of freedom (this would then be defined as the reaction coordinate) and in all the others, the curvature is positive. This negative force constant would lead to an imaginary frequency of vibration and the presence of this imaginary frequency would mean the transition state has been found.

Nf710 (talk) 11:03, 18 December 2017 (UTC) you can find the curvature of each dimensions at a point by taking the hessian matrix eiegenvalues

Computational methods

Two types of computational methods were utilised in this experiment: the semi-empirical method PM6 and the Density Functional Theory (DFT) method B3LYP. The PM6 method is based on the Hartree-Fock method (which treats the Hamiltonian with respect to electron position); however, it makes a lot of approximations and uses parameters taken from experimental data to solve the Hamiltonian matrix—meaning less integrals need to be calculated. This makes PM6 less expensive and faster than B3LYP but consequently, this method is less accurate.

Nf710 (talk) 11:04, 18 December 2017 (UTC) Excellent, good understanding

The B3LYP method is hybrid method that uses Hartree-Fock and DFT (which treats the Hamiltonian with respect to electron density). DFT is a faster method than Hartree-Fock because electron density is a function of only three variables-- x, y, z position of the electrons and its determination is independent of the number of electrons, unlike many-body wavefunctions.[2] DFT also improves on Hartree-Fock as it doesn’t neglect the correlated motions of electrons with anti-parallel spins. Therefore, B3LYP uses DFT to calculate every term in the Hamiltonian apart from the exchange correlation (DFT uses an approximation for this)-- this term is calculated using Hartree-Fock. Overall, B3LYP is more expensive and runs slower than PM6; however, it is much more accurate as it doesn't calculate integrals using experimental data.

Nf710 (talk) 11:12, 18 December 2017 (UTC) this is good, but there are a few bits you have confused. the reason why B3LYP uses HF for the XC term is to account for the fact that DFT cannot account the the uncorrelated nature of anti parallel spins (they can occupy the same position in a nucleus. See p53 https://chemistlibrary.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/modern-quantum-chemistry.pdf.) This problem is internet in all Quantum chemical calculations apart from coupled cluster. DFT hamiltonian is built in terms of a non interacting system and then you add in the XC at the end to account for the rest of the corrections. hence why al ot of quantum chemists see DFT as a 'dirty' method with lots of different functionals which are optimised for different systems.

Methods for finding the transition state

Method 1: A method that starts by estimating the structure of the TS and subsequently running a PM6 TS calculation and if successful, a B3LYP/6-31g(d) calculation is run. The disadvantage of this method is that a good knowledge of the TS is required for it to be reliable. If the initial guess structure is wrong, the calculation would just fail or the wrong TS would be found. This is, however, the fastest method.

Method 2: This is the fastest reliable method. An initial guess of the TS structure is also required; however, the structure is first optimised to a minimum before running a calculation to find the TS. This is done by freezing the atoms involved in the reaction (bond forming), this allows the rest of the structure to be optimised before calculating the TS. After this initial optimisation, a TS calculation by PM6 and/or B3LYP/6-31g(d) can be run. The disadvantage is that some knowledge of the TS is still required.

Method 3: This is the only method that does not require knowledge of the TS--making it the most reliable. The disadvantage is that it requires more steps and that it is difficult to apply if the TS is far away from the geometries of the minima. This method requires starting from either the reactants or products, optimising their structures and then altering the structure to correspond to how the reaction would proceed along the reaction coordinate to reach the TS. The atoms directly involved in the reaction are then frozen, the structure is optimised and from that, a TS calculation is run.

In this experiment, Method 2 has been used in Exercise 1 and 2, whereas Method 3 was used on Exercise 3.

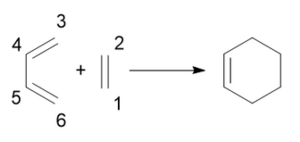

Reaction of butadiene and ethene

(Fv611 (talk) Excellent section. Clear, concise and correct. Very well done!)

Analysis of molecular orbitals

| MO | Butadiene | Ethene | Transition state | ||||||

| LUMO+1 | N/A | N/A | |||||||

| LUMO | |||||||||

| HOMO | |||||||||

| HOMO-1 | N/A | N/A |

A comparison of the molecular orbitals (MOs) of butadiene, ethene and the transition state shows us which orbitals in the two reactants interact and overlap during the formation of the transition state. Figure 2 and Table 1 show that the HOMO-1 MO of the TS is formed by the stabilising overlap of the HOMO of butadiene and LUMO of ethene; HOMO of the TS is formed by the stabilising overlap of the LUMO of butadiene and the HOMO of ethene; LUMO of the TS is formed by the destabilisng overlap of the LUMO of butadiene and the HOMO of ethene; and lastly, the LUMO+1 of the TS is due to the destabilising overlap of the butadiene HOMO and ethene LUMO. It can be seen that only orbitals of the same symmetry (both symmetric or antisymmetric) can overlap: HOMO of butadiene only overlaps with the ethene LUMO (both asymmetric) and the LUMO of butadiene only overlaps with the ethene HOMO (both symmetric). This means that a reaction is only allowed if the reactant MOs can fulfill this symmetry requirement and are able to overlap; otherwise, the reaction is forbidden if there is no MO overlap between reactants. The orbital overlap integral is zero for a symmetric-antisymmetric interaction; however, it is non-zero for symmetric-symmetric and antisymmetric-antisymmetric interactions.

This Diels-Alder reaction undergoes by normal electron demand because the energy gap between the butadiene HOMO and ethene LUMO is smaller than the energy gap between the ethene HOMO and butadiene LUMO.[3] The smaller energy gap between MOs means that there is a better overlap in the transition state. The energies were determined by running an IRC calculation on the TS and subsequently running an energy calculation on the two reactants and comparing energy levels of the MOs.

Changes to the carbon-carbon bond lengths

| C-C bond | Bond length/ Å | |||

| Butadiene | Ethene | Transition state | Cyclohexene | |

| C1-C2 | N/A | 1.3273 | 1.3818 | 1.5347 |

| C2-C3 | N/A | N/A | 2.1147 | 1.5371 |

| C3-C4 | 1.3353 | N/A | 1.3798 | 1.5008 |

| C4-C5 | 1.4684 | N/A | 1.4111 | 1.3370 |

| C5-C6 | 1.3353 | N/A | 1.3798 | 1.5009 |

| C6-C1 | N/A | N/A | 2.1148 | 1.5371 |

As the reaction progresses, the C1-C2 double bond in ethene lengthens and starts to form a single bond and the two C atoms turn from sp2 into sp3 centres to form new single bonds with C6 and C3, respectively. In butadiene, although C4 and C5 remain sp2 hybridised, the single bond between them becomes shorter as the double bond forms. The double bonds between C3-C4 and C5-C6 start to become single bonds; hence, the bond between these C atoms gets longer. C3 and C6 also become sp3 hybridised and form new single bonds with C2 and C1, respectively, and these are the new bonds forming between the two reactants and this can be seen in the bond distances of the TS in Table 2. These calculated bond distances of 2.1147 and 2.1148 Å are shorter than twice the Van der Waals radius of carbon, which is 1.7 Å, and this means that there is an interaction between the electron densities of the two carbon atoms and there is a partially formed bond in the TS.[4] Typical sp3 C-C and sp2 C=C bond lengths are 1.54 and 1.34 Å, respectively. These literature values match closely with the calculated bond lengths for butadiene, ethene and cyclohexene: the butadiene single C-C bond is slightly shorter due to the delocalisation of π electrons and the single bonds C3-C4 and C5-C6 in cyclohexene are shorter because one of the C atoms is an sp2 centre with more s orbital character-- making the bond slightly shorter than 1.54 Å.[5]

Reaction path at the transition state

This shows the vibration the TS takes in order to form cyclohexene. It shows that the C1-C2, C3-C4 and C5-C6 bonds are all elongating at the same time and the vectors show that the terminal C atoms of both reactants are moving closer together in the same direction to form new single bonds-- this means that the formation of the new bonds is synchronous. Step 10 in the IRC also shows that the two new single bonds form at the same-- meaning that the formation of the two bonds is synchronous.

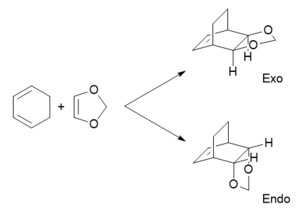

Reaction of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole

Analysis of molecular orbitals

(Fv611 (talk) Very nice MO diagram, although you could have added a discussion on the relative energies of the endo vs exo TS orbitals.)

| MO | Exo TS | Endo TS | ||||

| LUMO+1 | ||||||

| LUMO | ||||||

| HOMO | ||||||

| HOMO-1 |

An IRC calculation was ran on the the Exo TS, then the cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole geometries were extracted and an Energy calculation was ran on them separately. The comparsion of the energies of the reactant MOs revealed that the reaction undergoes inverse electron demand Diels-Alder. This is due to the fact that there is a smaller energy gap between the 1,3-dioxole HOMO and the cyclohexadiene LUMO compared to the energy gap between the cyclohexadiene HOMO and the 1,3-dioxole LUMO. This is possible in this system because the O atoms in 1,3-dioxole are electron-donating, which causes both the HOMO and LUMO energies to increase-- leading to inverse electron demand as the HOMO of the dienophile (1,3-dioxole) is now closer in energy to the LUMO of the diene (cyclohexadiene).[3]

Nf710 (talk) 11:16, 18 December 2017 (UTC) this is correct, probably easier to show with a diagram

Analysis of the thermochemistry

| Pathway | Activation barrier/ kJmol-1 | Reaction energy/ kJmol-1 |

| Exo | 166.30 | -65.14 |

| Endo | 158.48 | -68.75 |

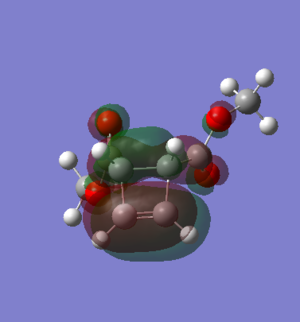

Figure 5: Endo product HOMO |

The activation barriers and reaction energies in Table 4 have been calculated using the "Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies" values taken from the thermochemistry data of the optimised structures of the reactants, TS and products. From the activation barrier data, it can be concluded that the endo product is more kinetically favourable as the activation barrier is lower compared to the exo pathway-- the energy required to reach the TS is lower. The reaction energy data also shows that the endo product is the more thermodynamically favourable product, as the reaction energy is lower (more negative) compared to the exo pathway-- the product formed has a lower energy and more thermodynamically stable. The reason for the lower activation barrier of the endo pathway is due to secondary orbital interactions, this can be seen in the HOMO of the endo TS in Table 3. This arises due to the overlap of p orbitals of the O atoms in 1,3-dioxole with the π electron density of cyclohexadiene-- this is a stabilising interaction that causes the TS to be lower in energy. This interaction is still present in the endo product HOMO (Figure 5), which explains why the endo product is also the thermodynamic product. However, this secondary orbital interaction is not available in the exo TS due to the wrong orientation of the 1,3-dioxole. A possible reason for the higher activation barrier of the exo pathway is that there is steric hindrance between the two CH2 groups of the bridgehead and the O atoms of 1,3-dioxole (Exo TS HOMO in Table 3)-- which is not present in the endo TS.

Nf710 (talk) 11:21, 18 December 2017 (UTC) This is very nice explanation. The argument for the endo being the thermo is more due to the fact it has less steric clashing than the exo. Your energies look correct well done. A diagram would have ben nice to explain the SSO.

Diels-Alder vs Cheletropic: O-xylylene-SO2 cycloaddition

IRC calculations for Exo/Endo Diels-Alder and Cheletropic pathways

The IRCs of the three different pathways are shown above, it can be seen that the exo and endo Diels-Alder pathways are both asynchronous as the C-O bond is formed faster than the C-S bond; whereas, the cheletropic reaction is synchronous as the two C-S bonds are formed at the same time. In all three reaction pathways, the bonding of the 6-membered ring in xylylene becomes a fully delocalised π electron system and the ring becomes aromatic. This makes xylylene highly unstable-- due to the strong driving force for aromatisation of the 6-membered ring and it can be seen in the IRCs that the aromatisation occurs faster than forming new bonds with SO2.

("are both asynchronous as the C-O bond is formed faster than the C-S bond" be careful here as GaussView uses distance thresholds to determine what a "bond" is. It's clear to say that they are formed at different times due to asymmetry, but not so trivial to say which is faster (different parameters for different atom pairs) Tam10 (talk) 15:32, 7 December 2017 (UTC))

Analysis of the thermochemistry

| Pathway | Activation barrier/ kJmol-1 | Reaction energy/ kJmol-1 |

| Exo | 88.40 | -97.02 |

| Endo | 84.42 | -96.41 |

| Cheletropic | 106.74 | -153.34 |

From Table 5, it can be seen that the favourable kinetic product is the endo product as it has the lowest acitvation barrier, this could be due to secondary orbital interactions caused by the p orbtials of the non-bonding O atom, which interacts with the π system of xylylene and stabilises the transition state. The cheletropic product is the more thermodynamically favoured product, as it has the lowest reaction energy-- this is due to the high bond energy of two S=O double bonds, making the product lower in energy and more stable.[6] However, the cheletropic TS has the highest activation barrier due to the ring and angle strain of the 5-membered ring formed-- this is less stable than a 6-membered ring formed in the exo and endo TS.

| Pathway | Activation barrier/ kJmol-1 | Reaction energy/ kJmol-1 |

| Exo | 122.47 | 23.35 |

| Endo | 114.63 | 18.91 |

An alternative Diels-Alder pathway can occur at the 6-membered ring fragment of xylylene and in Table 6, it can be seen that the activation barriers for these reactions are much higher compared to the previous site-- making these pathways very kinetically unfavourable. The reaction energies are also positive, which means that the reactions are endothermic and energy has to be put in to form products. This makes these pathways also thermodynamically unfavourable and this is because a stable aromatic ring is not formed in the TS or product. The conjugation with the other cis-butadiene fragment is also lost-- which is present in xylylene.

|

|

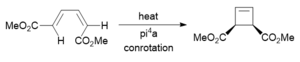

Electrocylic ring closing of a butadiene

Conrotatory or disrotatory

|

|

|

This electrocyclic reaction undergoes conrotation because it is a π4 system and it reacts antarafacially.[3] Figure 13a shows that the HOMO of the butadiene fragment in the reactant is antisymmetric and a conrotation will allow for a stabilising in-phase overlap of the MOs. In Figure 13b, the formation of a strong end-on overlap of the MOs in the TS can be seen and this end-on overlap transforms into a strong σ-type bond in the product-- this can be seen in Figure 13c. This conrotation and overlap of MOs can be seen more clearly in Figure 12.

(This is interesting to see. You can see how the double bonds are transferred to a single double bond (resembling the LUMO) without accessing the LUMO. You should state what method you have used here, even though it is clear in your files. Would be good to see energetics. Tam10 (talk) 15:43, 7 December 2017 (UTC))

(+10% Tam10 (talk) 15:43, 7 December 2017 (UTC))

Conclusion

In conclusion, the combination of using PM6 and B3LYP methods of calculation allowed to predict the feasibility of the cycloaddition reaction pathways studied. PM6 provided a quick calculation of the TS geometries and B3LYP provided more accurate results. The close comparison of C-C bond lengths with literature in Exercise 1 proved the reliability of these computational methods.

In Exercise 1 and 2, visualisation of the MOs allowed to distinguish Diels-Alder reactions between normal or inverse electron demand and the importance of MO symmetry in predicting whether reactions are allowed or forbidden. Analysis of the negative frequency of vibration of the TS in Exercise 1 showed that the bond formation to form the cyclic product is synchronous. In Exercise 2 and 3, analysis of thermochemistry of the reactants, TSs and products allows prediction of the thermodynamic and kinetic products when a reaction has multiple pathways--where it was found that the kinetic and thermodynamic product is the endo product in Exercise 2. Whereas in Exercise 3, it was found that the kinetic product is the endo product but the thermodynamic product is the cheletropic product. In the investigation of the electrocyclic ring closing of a butadiene, the visualisation of the HOMO of the reactant, TS and product provided evidence for the conrotatory requirement of the reaction.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 I. N. Levine, Physical chemistry, McGraw-Hill, New York ; London, 4th ed. edn., 1995.

- ↑ Marques, M. A. L.; Gross, E. K. U. Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory; Springer: New York, 2003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 J. Clayden, N. Greeves and S. G. Warren, Organic Chemistry, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2nd edn., 2012.

- ↑ S. S. Batsanov, Inorg. Mater., 2001, 37, 871-885.

- ↑ L. Pauling and L. O. Brockway, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1937, 59, 1223-1236.

- ↑ E. Lippert, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. , 1960, 72, 602-602.

LOG files

Exercise 1

Exercise 2

LOG file of B3LYP cyclohexadiene,

LOG file of B3LYP 1,3-dioxole,

LOG file of B3LYP Exo product,

LOG file of B3LYP Endo product

Exercise 3

LOG file of PM6 Cheletropic TS,

LOG file of PM6 IRC Cheletropic TS,

LOG file of PM6 Cheletropic product

Alternative site:

LOG file of PM6 Exo TS (Alternative site),

LOG file of PM6 IRC Exo TS (Alternative site),

LOG file of PM6 Exo product (Alternative site),

LOG file of PM6 Endo TS (Alternative site),

LOG file of PM6 IRC Endo TS (Alternative site),

LOG file of PM6 Endo product (Alternative site)