Rep:Mod:jh2810B

James Hayward - Second Submission

Modelling Using Molecular Mechanics

Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Formation

Process

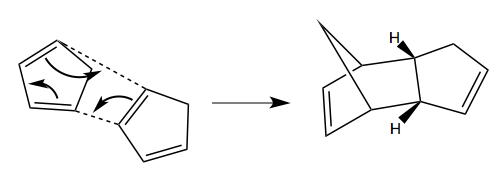

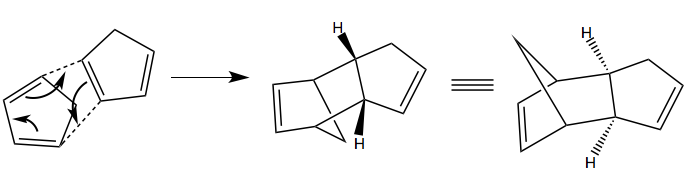

Cyclopentadiene readily forms dimers at room temperature, by [3+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition with itself (being both a potential diene and a dieneophile). The mechanism for the formation of the two possible dimers is shown below:

Data

The exo and endo products were then drawn in ChemBio3D, and their structures were optimised to a minimum energy using the MM2 method (Allinger's). Diagrams of the structures are shown, as well as a table of their total energies and their compositions.

Analysis

The energies show that the endo product is slightly higher in energy, with the major difference between the two forms coming in the Torsion energy. This is as expected from literature, which agrees that the exo product is slightly more thermodynamically stable[1], but also indicates that the endo product dominates. [2]

It can be seen from the table that the component which contributes most to the difference in energy is the torsion. This energy difference can be accounted for by studying the different dihedral angles in the carbon structure.

Figure 5 and figure 6 show images of the two compounds such that they show side views of the longest carbon chain structures. In the exo-dimer (Fig. 5), the dihedral angle of 179o shows that this structure is approximately antiperiplanar along this central bond. The endo-dimer has a dihedral angle of -51o, indicating that the structure is closer to the gauche confirmation along the carbon backbone.

From computational analysis of simple linear hydrocarbons [3], gauche confirmations are higher energy than antiperiplanar (app) conformations. The analysis of a simple butane system in this example an energy difference of 0.5 kcal/mol is observed. Considering that there are two bonds that are either gauche-gauche or app-app, and also that the gauche dihedral angles in the endo-dimer are a significant 9o from the ideal 60o conformation due to other strain in the molecule (e.g. at the double bonds, in the bridge etc.), it seems that this energy is sensibly comparable to the ~2kcal/mol difference between the endo and exo dimers.

Why the Endo Dimer is Favoured

The reason why the endo-dimer is favoured despite the slightly higher energy is due to the secondary orbital stabilisation in the formation. This stabilises the transision state. Unfortunately, the MM2 method cannot be used to determine the energy of the transition state, but this could be calculated using a different method accessible via ChemBio3D or GaussView. Although the computation of the transition state is not included in this exercise, the following diagrams illustrate where the stabilisation of the endo-transition state comes from.

Hydrogenation

Data

This table shows the energy comparison between the two possible hydrogenation products from the endo-cyclohexadiene dimer. The first row (from figure 9) shows hydrogenation at the bicyclic double bond (giving Product 3), and the second row (from figure 10) shows hydrogenation at the cyclic double bond.

Analysis

Product 4 is thermodynamically more stable; it has an overall energy of 31.15 kcal.mol-1 compared with 35.69 kcal.mol-1 for product 3. This time the largest contributor to the overall difference in energy is the bending energy, with Product 3 being 5.34 kcal.mol-1 higher in energy. This difference is actually larger than the overall difference in energy (of 4.54 kcal.mol-1), but this is balanced by the torsion energy of 4 being 1.70 kcal.mol-1 larger.

The main difference in the bending energy is due to the different bond angles at the sp2 carbon atoms. Figures 11 and 12 show the difference between these bond angles for the two products. Product 3 (figure 11) has a sp2 bond angle of 108o, and Product 4 (figure 12) has a sp2 bond angle of 112o. The minimum energy angle for sp2 occurs at 120o, so it is clear from this reasoning that product 4 will be lower in energy, as it is closer to the minimum than product 3.

The difference in the torsional strain energy comes from the degree to which hydrogenation of the double bond relieves strain in the different parts of the molecule. In product 3, the hydrogenation relieves the strain in the 5 membered ring, whereas in product 4, the strain is relieved in the bicyclic 5/6 membered rings. The relief of strain in the bicyclic system is smaller because the hydrogenated system remains quite highly strained. Therefore by this reasoning alone, the hydrogenation of the 5 membered monocycle is favoured as it produces the greater reduction in torsion energy. However, as previously explained, this effect is smaller than the effect of the bending energy, and therefore, Product 4 dominates thermodynamically.

To determine whether kinetics or thermodynamics dominates in this reaction, the transition states and frontier molecular orbitals would need to be studied. Molecular mechanics theory does not allow for this, although other methods would make this determination possible.

Introduction

The compounds used in this section (intermediates in the synthesis of Taxol proposed by Paquette [4][5]) display a very good example of atropisomerism. Explanation of the concept fully, as well as may more examples can be found in the literature [6]. The atropisomerism in this example comes from the restriction in rotation about the bonds connecting the two smaller cyclic systems in the molecule. They can be differentiated by the direction of the carbonyl group, with "up" meaning pointing (direction; C to O) the same way as the end of the 5 membered ring with the quaternary carbon atom, and "down" meaning pointing in the opposite direction.

Data

The two isomers of the Taxol intermediate were drawn and then minimised by MM2 theory (and then by MMFF94 theory), to give the products and energies as follows:

| Compound | Image | Stretch /kcal.mol-1 | Bend /kcal.mol-1 | Stretch-Bend /kcal.mol-1 | Torsion /kcal.mol-1 | Non-1,4 VDW /kcal.mol-1 | 1,4 VDW /kcal.mol-1 | Dipole/Dipole /kcal.mol-1 | Total Energy (MM2) /kcal.mol-1 | Total Energy (MMFF94) /kcal.mol-1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound 9 (Figure 13) |

|

2.78 | 16.54 | 0.43 | 18.25 | -1.56 | 13.11 | -1.73 | 47.84 | 70.55 | |||

| Compound 10 (Figure 14) |

|

2.60 | 10.42 | 0.29 | 19.37 | -2.21 | 12.92 | -2.01 | 41.38 | 61.21 |

Computing both Isomers

The key part to simulating the two isomers is in getting the correct orientation of the cyclohexane ring relative to the carbonyl group, and then optimising the cyclohexane ring into an accurate chair conformation. Although easy to achieve for the first ("up") isomer, simple adding the structure of the "down" isomer and minimising resulted in flipping of the system back to the "up" isomer. Therefore, the structure of the "down" isomer was achieved by starting from the "up" isomer and building a second cyclohexane ring alongside the first one, before deleting the first ring to leave the opposite stereochemistry in the structure. This new structure was then reoptimised to give the "down" isomer.

Energy Comparison

In terms of energy, compound 10 (the "down" isomer) is the thermodynamically more stable species by 6.46 kcal.mol-1 (by MM2 theory) or 9.34 kcal.mol-1 (by MMFF94 theory); see final 2 columns of table 4. Although the two levels of theory give a different value for the energy, the relative energies for the two calculations agree to 3 significant figures (energy(compound 9) = 1.15 * energy(compound 10).

Of the energy components, the major difference again lies with the bending energy, as MM2 theory shows Compound 10 having a lower bending energy by 6.12 kcal.mol-1. This is probably due to the rigid structure of the carbon backbone which connects the 5 and 6 membered rings at either end, and causes the atropisomerism.

Hyperstable Alkenes

This compound is an example of a phenomenon known as hyperstability of alkenes. First formally recognised in the literature here[6], this class of compounds is unique in that the alkene is less strained than the parent hydrocarbon, and therefore "should show decreased reactivity due to the bridgehead location of the double bonds". There are many other examples given in the paper, but this is an excellent example, explained as follows:

Figure 15 shows the "up" isomer (Compound 9) with the sp2 bond angle shown as 124o, only 4o from the expected (non-strained) minimum at 120o. Then, the double bond was replaced with a single bond, and the new structure optimised (all at MMFF94 level of theory). It is shown in figure 116, with the same bond angle (now sp3) shown. However, this bond angle is still 121o, when an expected (non-strained) sp3 would be 109.5o. This gives some indication of the predicted reactivity; despite double bonds normally being more reactive than single bonds towards electrophiles, the extremely high strain in the alkane species here would mean that it is more reactive than the alkene. Therefore, the alkene species observed is described as "hyperstable", and will show significantly less reactivity than a free alkene.

Modelling Using Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective addition of Dichlorocarbene to a diene

Introduction

The use of semi-empirical molecular orbital theory is a solution to several of the problems encountered with using the simpler molecular mechanics approach. Some of the advantages of using molecular orbital theory in computation are shown with the following examples.

Use of MM2 Theory

The following section shows the effect of introducing molecular orbital theory on the properties of the diene compound shown. First tthe molecule is minimised using HH2 theory, and energies and image are displayed as previously.

| Compound | Image | Stretch /kcal.mol-1 | Bend /kcal.mol-1 | Stretch-Bend /kcal.mol-1 | Torsion /kcal.mol-1 | Non-1,4 VDW /kcal.mol-1 | 1,4 VDW /kcal.mol-1 | Dipole/Dipole /kcal.mol-1 | Total Energy (MM2) /kcal.mol-1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound 12 (Figure 17) |

|

0.62 | 4.74 | 0.04 | 7.66 | -1.07 | 5.79 | 0.11 | 17.89 |

Comparison to MOPAC Theory

Now this can be compared to the MOPAC RM1 level of theory, which takes Molecular orbitals into account. The following .jmol animation shows the structure as optimised at the new level of theory. This calculation also gives a value for the energy (RM1 energy = 32.19 kcal.mol-1).

|

|||

| Figure 18: Taxol intermediate (Compound 9) with MOPAC theory |

The visible differences between the two molecules are not immediately obvious. However, superimposition of the resultant molecules from each level of theory clearly shows a significant difference in the computed structures. In the following diagram, the MM2 optimised structure is highlighted and the two structures overlay such that the H-C=C-H on the side furthest from the Cl atom have the maximum possible overlay (minimum possible separation).

The diagram clearly shows the influence of the molecular orbital calculation. The chlorine atom clearly affects bending of the ring structure away from the near-planarity, as predicted by the MM2 calculation. This is because of the large effect the chlorine atom has on the molecular orbitals; although not much larger in size than a carbon atom (and therefore not much different in the MM2 properties), it's electronegativity is the key factor in influencing the molecular orbitals.

Calculating Molecular Orbitals

The key (frontier and surrounding) molecular orbitals of the diene were calculated by MOPAC PM6 method and are shown here:

Reactivity

The images show a clear difference between the HOMO and LUMO in distribution across the molecule. The HOMO is strongly biased towards the C=C bond adjacent to the chlorine, whereas the LUMO is strongly biased towards the opposite C=C bond. Therefore this gives a very good indication of the expected reactivity; i.e.

- The C=C п-bond syn to the Cl group is the best site for electrophilic attack (e.g. of dichlorocarbene, as in the example)

- The C=C п-bond antito the Cl group is the best site for nucleophilic attack

It is possible that the stabilisation of the double bond syn to the Cl atom comes from a stabilising interaction between the C-Cl σ* orbital and the C=C п orbital. This is then reflected in the overall combined molecular orbitals, and causes the split int the HOMO/LUMO location and energy.

In terms of molecular symmetry, with both double bonds the compound has Cs symmetry with a mirror plane through the C-Cl bond. However, if either double bond undergoes addition then this symmetry is lost. The vibrational frequencies of the molecule were then calculated and the spectra are shown below.

Vibrations and Spectra

Figure 21: The IR spectrum of the diene molecule

Monosaccharide chemistry and the mechanism of glycosidation

Introduction

This section studies the process of glycosidation. This involves substitution of a leaving group adjacent to the ring oxygen in monosaccharides with a nucleophile. The mechanism by which this occurs involves a neighboring group effect from the adjacent acetyl group, and is shown below:

This mechanism effectively blocks one side of the anomeric carbon where the substitution occurs. This means that when the acetyl group is orientated downwards (e.g. in A), the β-anomer product is exclusively formed. Equally, when the acetyl group is orientated upwards (e.g. in C), the α-anomer product is formed.

The R group chosen for these computations was the methyl group. Larger groups with lengthy alkyl chains or simply more atoms would result in lengthy and variable calculation results. An even smaller H group could have been used, but as this would result in hydrogen bonding within the molecule, -OH groups were not used.

Structures A/A* and C/C* represent different conformations of the structure after the leaving group has gone (leaving a cation on oxygen), and the B/B* and D/D* structures represent the closed 5 membnered ring with the cationic charge on the carbonyl oxygen. These structures are all summarised in figure XX:

The difference denoted by the star for A and C comes from orientating the carbonyl in the other direction so it faces away from the bond about to form. In structures A and C, there is a stabilising interaction between the δ -ve carbonyl oxygen and the δ +ve anomeric carbon atom. In A* and C* this interaction is not present, so they are higher energy.

For B and D it represents the difference between having the oxygens in the 5 membered ring anti or syn to each. B and D show the syn-ring structure and B* and D* show the higher energy (more strained) anti-ring structure.

Energy table

| Compound | Stretch /kcal.mol-1 | Bend /kcal.mol-1 | Stretch-Bend /kcal.mol-1 | Torsion /kcal.mol-1 | Non-1,4 VDW /kcal.mol-1 | 1,4 VDW /kcal.mol-1 | Charge/Dipole /kcal.mol-1 | Dipole/Dipole /kcal.mol-1 | Total Energy MM2 /kcal.mol-1 | Jmol/MM2 | Total Energy MOPAC/PM6 /kcal.mol-1 | Jmol/MOPAC/PM6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.50 | 12.41 | 0.94 | 2.62 | 2.42 | 19.90 | -42.78 | 8.33 | 6.34 | -91.66 | ||

| A* | 2.33 | 10.93 | 0.82 | 2.34 | -0.92 | 19.94 | -22.47 | 5.24 | 18.21 | -85.04 | ||

| B | 1.99 | 13.22 | 0.69 | 7.47 | -2.55 | 17.71 | -10.86 | -0.64 | 27.04 | -91.66 | ||

| B* | 2.75 | 17.99 | 0.86 | 7.99 | -2.30 | 19.19 | -1.03 | -0.12 | 47.48 | -66.88 | ||

| C | 2.83 | 12.98 | 1.06 | 2.05 | 3.56 | 19.03 | -36.76 | 7.01 | 28.04 | -91.66 | ||

| C* | 2.39 | 14.61 | 1.01 | 1.61 | -3.20 | 18.83 | -1.68 | 6.28 | 39.87 | -63.45 | ||

| D | 1.99 | 13.08 | 0.68 | 7.45 | -2.54 | 17.72 | -10.49 | -0.54 | 27.36 | -91.66 | ||

| D* | 2.69 | 16.98 | 0.75 | 7.65 | -2.89 | 19.32 | 4.50 | -0.76 | 48.25 | -65.42 |

N.B. due to the rotation of the methyl groups, it is likely that these energies are slightly incorrect, as repeats of the calculation showed a small fluctuation of the final energy result. However, these differences were small enough that they did not effect the relative energies of each of the species.

Introduction

The objective of this section is to produce a NMR spectrum for another intermediate in the synthesis of taxol (figure XX). It involves using a Gaussian interface with the RB3LYP/6-31G(d,p) method to first optimise the molecule, then produce the H and C NMRs before comparing to literature. [7]

This is used as a preparation for the module which follows, which involves a full comparison of computed data to a literature reaction involving formation of 2 different isomers.

Spectra

1H NMR

Computed

Figure 24: 1H NMR Spectrum of Taxol intermediate

Literature

'H NMR (300 MHz, c&) 6 5.21 (m, 1 H), 3.00-2.70 (m, 6 H), 2.70-2.35 (m, 4 H), 2.20-1.70 (m, 6 H), 1.58 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1 H), 1.50-1.20 (3 H), 1.10 (s, 3 H), 1.07 (s, 3 H), 1.03 (s, 3 H)

Comparison

H NMR

From literature: 6-5.21 (m, 1H), 3.00-2.70 (m, 6 H), 2.70-2.35 (m, 4 H), 2.20-1.70 (m, 6 H), 1.58 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1 H), 1.50-1.20 (3 H), 1.10 (s, 3 H), 1.07 (s, 3 H), 1.03 (s, 3 H)

Computed spectrum: 6.02, 3.53, 3.18, 3.12, 3.01, 2.93, 2.79, 2.59, 2.21, 2.10, 2.02, 1.90, 1.84, 1.78, 1.63, 1.51, 1.33, 1.19, 1.04

| δ(calculated) (corrected) (ppm) | δ(literature) (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 6.02 | 6-5.21 (m, 1H) |

| 3.53 | 3.00-2.70 (m, 6 H) |

| 3.18 | " |

| 3.12 | " |

| 3.06 | " |

| 2.93 | " |

| 2.79 | " |

| 2.59 | 2.70-2.35 (m, 4 H) and 2.20-1.70 (m, 6 H) |

| 2.21 | " |

| 2.10 | " |

| 2.02 | " |

| 1.90 | " |

| 1.84 | " |

| 1.78 | " |

| 1.63 | " |

| 1.51 | 1.58 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1 H) |

| 1.33 | 1.50-1.20 (3 H) |

| 1.19 | 1.10 (s, 3 H) |

| 1.04 | 1.07 (s, 3 H), 1.03 (s, 3 H) |

13C NMR

Computed

Figure 25: 13C NMR Spectrum of Taxol intermediate

Literature Results

13C NMR (75 MHz,(m, C6D6) ppm 211.49, 148.72, 120.90, 74.61, 60.53, 51.30, 50.94, 45.53, 43.28, 40.82, 38.73, 36.78, 35.47, 30.84.30.00, 25.56, 25.35, 22.21, 21.39, 19.83;

Comparison

The following table shows how the computed results map to the literature results. Although the extremes lie in the same place, and thus the solvation/method would seem to be correct, the central peaks show a fairly large divergence from the literature values. The level of error here will be compared to that for the literature module which will be done next.

| δ(calculated) (corrected) (ppm) | δ(literature) (ppm) |

|---|---|

| 24.69 | 19.83 |

| 25.52 | 21.39 |

| 27.17 | 22.21 |

| 27.47 | 25.35 |

| 28.72 | 25.56 |

| 30.51 | 30.00 |

| 33.91 | 30.84 |

| 40.36 | 35.47 |

| 45.81 | 36.78 |

| 47.55 | 38.73 |

| 50.57 | 40.82 |

| 52.02 | 43.28 |

| 57.56 | 45.53 |

| 60.48 | 50.94 |

| 62.21 | 51.30 |

| 124.36 | 60.53 |

| 151.13 | 74.61 |

| 1.19 | 120.90 |

| 219.28 | 148.72 |

| 211.49 |

Infrared

Computed

Figure 26: IR Spectrum of Taxol intermediate

Literature results

"IR (cm-l) 3070-2800, 1675, 1470, 1390, 1345, 1275, 1260-1200, 1170, 1050"

Comparison

Unlike with the NMR data, the infrared prediction maps very well with the literature data. All the peaks from the literature are prominent and close to their expected location.

Regio- and Stereoselective Synthesis of Cyclic Imidates via Electrophilic Cyclisation of 2-(1-Alkynyl)benzamides[8]

Introduction

This section relates to the study of a recent piece of literature which reports production of 2 isomeric products. The example I have chosen relates to the formation of cyclic imidates from an alkynyl benzamide starting material. The literature reports formation of either a 5 member or 6 member ring attached to the benzene ring, with the alkyne reacting with the carbonyl oxygen to give an oxygen containing cycle. The reaction scheme, with the 2 experimentally confirmed products is shown below.

Reaction Scheme

Structures

The following table shows a classification and comparison of the two products by three different levels of theory:

| Compound | 6-5 structure | 6-6 structure |

|---|---|---|

| Full Name: | N-[(E)-3-(Iodo(phenyl)methylene)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-ylidene]aniline | N-(4-Iodo-3-phenyl-1H-isochromen-1-ylidene)aniline |

| align="center" colspan="3" ! Energy /kcal.mol-1 | ||

| BY3LYP: | -7823.4849 | -7823.4880 |

| Structure | ||

| MOPAC/PM6: | 97.65267 | 90.35449 |

| Structure | ||

| MM2: | 49.5879 | 56.2203 |

| Structure |

The three levels of theory give very different results; not only in that they are different magnitude, but the theories do not agree on the compound which is higher energy. The highest level of theory used here (the BY3LYP theory, run via Gaussian) shows that the two products are practically identical in energy (with a difference of just 0.00004%). Therefore, this suggests that as the products are thermodynamically equally likely to form, the more important factor to consider in deciding which product will predominate is the study of kinetics.

There is other evidence that suggests this from the literature. It is shown that changing the reaction conditions (e.g. using I2 + NaHCO3 in acetonitrile for 1h at RT under Ar vs. using ICl with no base in chloroform for 0.5h at RT under Ar) changes the product ratio considerably. This points towards use of kinetic control as the primary method to determining product ratio.

|

|

The best way to determine the difference between these two isomers would probably be to look at the subtle differences in the IR spectra. The proximity of the iodine atom to the oxygen and nitrogen changes by one bond between the structures, so you would expect this to have an effect, probably in the location of the single prominent peak produced. Also, if the finestructure of the IR could be studied, you would expect to see different ring-wagging modes for the 5 and 6 membered rings.

In addition to this, a different fragmentation pattern would be expected in the Mass spectrometry. A significant fragment of the double ring structre would be expected, and this would be different by 13 AU in each case (depending on the number of Hydrogens that remain attached).

Spectra

N-[(E)-3-(Iodo(phenyl)methylene)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-ylidene]aniline

13C NMR

Figure 30: 13C NMR Spectrum of 6-5 ring compound

Literature

13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 124.1, 125.07, 125.1, 125.4, 128.1, 128.7, 130.5, 130.9, 132.0, 132.8, 135.8, 140.6, 145.0, 147.8, 152.0 (one carbon missing due to overlap)

Comparison

COMPUTED: 92.8, 94.0, 97.18, 99.54, 99.68, 100.08, 100.56, 101.42, 102.61, 103.30, 103.96, 104.77, 104.90, 105.58, 107.02, 109.39, 113.39, 117.81, 117.24, 123.84, 126.87

Here the literature data is significantly different from the computed data. Although the extremes of the peaks are approx. 30ppm apart in both cases, the range is out by and additional 30ppm. This could be due to used of an incorrect reference, or an error in the solvation model resulting in all carbons changing shielding significantly. Either way, the comparison is too vague to make a significant comparison.

1H NMR

Figure 31: 1H NMR Spectrum of 6-5 ring compound

Literature

1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.09 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.22–7.36 (m, 7H), 7.59–7.73 (m, 4H), 8.05 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.86 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H)

Comparison

COMPUTED: 5.79 (2- 31,30), 6.04 (1- 33), 6.15 (2- 36,37), 6.24 (3- 35,32,25), 6.32 (2- 29,34), 6.48 (1- 38), 6.55 (2- 26,28), 7.25 (2- 26,28)

Again, the difference between the literature and computed spectra are very large. This is an example where further study would be needed to determine the reasons and causes of this difference.

Infrared

Figure 31: IR Spectrum of 6-5 ring compound

Literature

Literature: IR (neat, cm–1) 1684

Comparison

This value agrees well with the generated spectrum shown above. Also, the fact that there is only a single prominent peak (like in the literature) gives a good indication this structure is correct.

N-(4-Iodo-3-phenyl-1H-isochromen-1-ylidene)aniline

Figure 32: 1H NMR of 6-6 ring compound

1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.06 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.33 (m, 4H), 7.39–7.41 (m, 3H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.67 (m, 3H), 7.76 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.40 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H)

COMPUTED: 5.33 (1H- 31), 5.47 (1H- 30), 5.78 (2H- 33, 25), 6.01 (1- 28), 6.12 (1- 32), 6.21 (5- 36,26,35,37,29), 6.31 (1- 27)

Figure 33: 13C NMR of 6-6 ring compound

13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 123.1, 124.0, 124.1, 127.7, 128.2, 128.9, 129.4, 130.1, 130.2, 131.5, 133.2, 135.0, 135.6, 146.1, 148.7, 153.4

COMPUTED: 132.00, 120.35, 119.17, 109.03, 108.36, 107.24, 105.55, 105.47, 104.78, 104.12, 103.70, 102.72, 103.71, 102.72, 102.07, 101.91, 97.50, 94.56, 93.56, 92.23, 85.77

Figure 34: IR Spectrum of 6-6 ring compound

Literature: IR (neat, cm–1) 1645.

Similar comparisons can be made for the 6-6 ring compound as the 6-5 ring, with the IR spectra being closest to the literature values. Also, the single, prominent, infrared peaks are clearly different, so this would be the best way to determine which isomer was formed and at what approximate ratio.

Conclusion

The computation has shown that the two isomers in the chosen literature reaction are very similar in energy. It has also shown that accurate computed reproductions of the IR spectra can be produced. However, it has shown also that although NMR spectra can be computed, more refinement of the method is needed in order to reproduce the literature spectra exactly, as the model seems to not be very accurate when it comes to prediction of shielding.

References

- ↑ D. Hönicke, R. Födisch, P. Claus, M. Olson, 2000, Cyclopentadiene and Cyclopentene, Ullman's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry DOI:10.1002/14356007.a08_227

- ↑ W. C. Herndon, C. R. Grayson, J. M. Manion, J. Org. Chem., 1967, 32, 529 DOI:10.1021/jo01278a003

- ↑ H. Rzepa, Conformational Analysis Template:Http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/local/organic/conf/

- ↑ S.W. Elmore, L.A. Paquette, Tetrahedron Lett., 1991, 32, 219 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ L.A. Paquette, N.A. Pegg, D. Toops, G.D. Maynard, R.D. Rogers,J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277 DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bringmann, G., Price Mortimer, A. J., Keller, P. A., Gresser, M. J., Garner, J. and Breuning, M. (2005), Atroposelective Synthesis of Axially Chiral Biaryl Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 44: 5384–5427. DOI:10.1002/anie.200462661 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Six" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 227-283 DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ S. Mehta, T. Yao, R. C. Larock, J. Org. Chem., Article ASAP DOI:10.1021/jo301958q