Rep:Mod:jessrocks2

Kandeeban Gopalakrishnan CID:00602999

Introduction

This module will use Gaussian in order to calculate bond lengths, angles and various other properties in order to determine the structure of a compound. In this day and age, computational chemistry has become an ever-more reliable tool for chemists. The large resources available and low cost associated with such a method makes it a more viable option compared to more traditional ‘wet’ experiments.

In the Gaussian program, different basis sets will be tested and compared in order to obtain a good representational of a molecule’s orbitals. Each and every molecule have slightly different components and may need a different basis set in order to obtain a very accurate depiction of their correspondng orbitals. Let us take a slightly deeper look into the term ‘basis sets’. It is a set of wave-functions (expressed mathematically)[1] that accurately represents the molecular orbitals of a molecule. Furthermore, although minimal basis sets can be used to get a rough depiction, constraints on the each atom make this basis set makes these set much less accurate compared to pople basis sets. This basis set includes the 6-31g and 6-311g sets which will be frequently used within this module.

In addition to this, Density Functional Theory (DFT) is an approximation method that will also be used throughout this module; although the main limitation to this method (and most others) is that the exact solution cannot be obtained, DFT does give a much better approximation compared to methods such as Hartree-Fock (HF) and Molecular Mechanics (MM) methods[2].

A variety of these methods will also be applied in the mini-project in order to examine the extent of Pi back-bonding in various Metal hexacarbonyls. The computationally calculated results will then be compared to literature sources in order to determine the reliability of these computational methods.

BH3 Molecule Optimisation

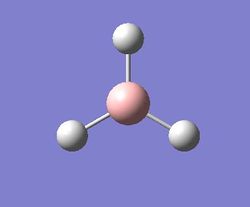

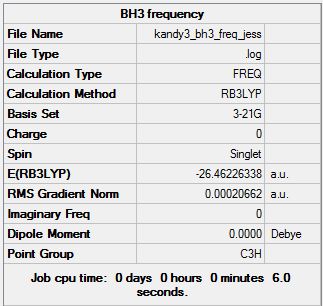

As stated in the instruction page, the BH3 molecule was drawn on Gaussview. In addition to this, each B – H bond length was set to 1.5 Angstroms and the molecule was then optimised using the 3-21g basis set (and B3LYP method) in order to attain the optimised geometry of the BH3 molecule. This allows a quick and moderately accurate calculation to be performed [3]. The 3D model of the optimised molecule can be seen below:

|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000017 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000010 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.883324D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

----------------------------

! Optimized Parameters !

! (Angstroms and Degrees) !

-------------------------- --------------------------

! Name Definition Value Derivative Info. !

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

! R1 R(1,2) 1.1943 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! R2 R(1,3) 1.1944 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! R3 R(1,4) 1.1944 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A1 A(2,1,3) 120.0005 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A2 A(2,1,4) 120.0005 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A3 A(3,1,4) 119.999 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! D1 D(2,1,4,3) 180.0 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

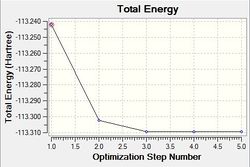

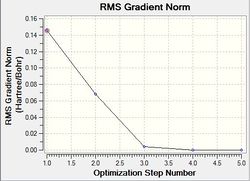

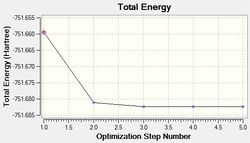

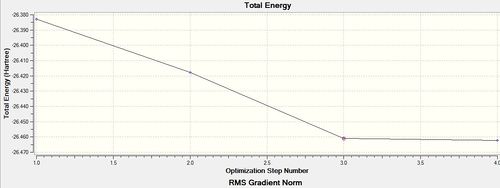

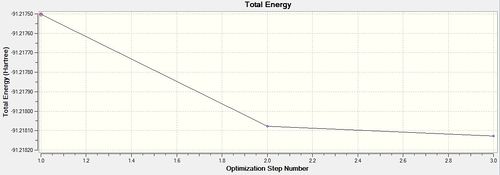

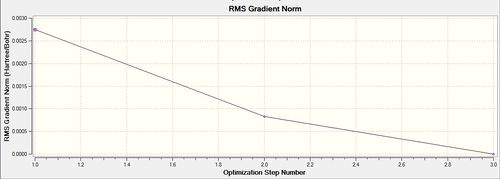

Optimisation using the Density Functional Theory (DFT) method allows one to calculate the optimum position of the nucleus in comparison to the electronic structure. Optimisation of the molecule can be followed in the graphs shown below (figure xx) and the structures of the various structures are also shown below (figure xx). Iterations were performed until a gradient of zero was achieved for the ‘total energy’ plot and total convergence was achieved (shown above).

The first derivative is used to determine whether a minimum or maximum has been achieved; however, in order to determine the real nature of this peak (minimum in this case), the second derivative must be analysed. By looking at the IR frequencies, there are no negative frequencies present, thus confirming the presence of the energy minimum (the presence of negative frequencies would arise if a transition state was formed). These frequencies are displayed in the ‘IR analysis’ section.

|

|

|

|

As stated earlier, the intermediates of the optimisation were obtained in order to analyse this process. Evidently, it can be seen that 3 iterations; the four intermediates, which result from each of these iterations, are shown above. As indicated by the total energy curve, the last intermediate (intermediate 4) has the lowest energy configuration. Intermediate 1 and 2 don’t have bonds displayed; however, this is because Gaussview regards a bond in terms of the inter-molecular distance (pre-set value). As the actual bond length is slightly longer than this, Gaussview is unable to display them visually.

Figure xx and Figure xx show the bond angle and the optimal bond distance respectively. After geometric optimisation, a bond length of 1.193 Angstroms[4] was obtained. This value is in agreement with the literature bond length of 1.19001 Angstroms. In addition to this, a bond angle of 120 degrees was obtained, thus confirming that the optimal structure of the BH3 molecule is trigonal planar[5].

Natural Bond Order (NBO) analysis allows us to see the distribution of electron density within the whole molecule. This can be used to determine the bonding activity involved in BH3. Table 3 represents the charge distribution within the molecule. It illustrate the role of BH3 as a lewis acid; the green area illustrates the lack of electron density in the region while the green area shows an abundance of electron density in a certain area. The Boron atom appears to be fairly electron deficient while a large amount of electron density seems to reside in the Hydrogen atoms. The role of BH3 as a Lewis acid is due to the presence of six valence electrons. In order to obtain full octet (shell), it must accept electrons from elsewhere. This analysis also confirms that Hydrogen is more electronegative than Boron, resulting in the electron distribution stated above.

Summary of Natural Population Analysis:

Natural Population

Natural -----------------------------------------------

Atom No Charge Core Valence Rydberg Total

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

B 1 0.19785 1.99962 2.80253 0.00000 4.80215

H 2 -0.06595 0.00000 1.06582 0.00013 1.06595

H 3 -0.06595 0.00000 1.06582 0.00013 1.06595

H 4 -0.06595 0.00000 1.06582 0.00013 1.06595

=======================================================================

* Total * 0.00000 1.99962 5.99998 0.00040 8.00000

The Natural Population Analysis numerically confirms this explanation. Here, one can see that in arbitrary terms, there are 2.80253 electrons. As there is supposed to be 3 valence electrons in the valence shell of Boron, the difference in electron density (~0.2 of an electron) is spread across the 3 H atoms. This illustrates the electronegativity difference between the Boron and Hydrogen atoms.

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.8165 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 2 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

2. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 3 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

3. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 -0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 4 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

4. (1.99903) CR ( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

5. (0.00000) LP*( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

6. (0.00000) RY*( 1) B 1 s( 0.00%)p 1.00(100.00%)

7. (0.00000) RY*( 2) B 1 s( 0.00%)p 1.00(100.00%)

8. (0.00000) RY*( 3) B 1 s( 0.00%)p 1.00(100.00%)

The values above show the relative contributions from the Boron and Hydrogen atom for each bond. It shows that the Boron contributes 44.5% of the bond while the Hydrogen atom contributes to 55.5% of the bond. In addition to this, the table shows that the 1s orbitals of the Hydrogen atom interacts with the sp2 hybridised Boron orbitals (this is shown by the 33.33% s character: 66.67% p character). Furthermore, it can be seen that there is a p(Z) lone pair present on the Boron atom (this is indicated on Lines 8,9 and 10).

IR Analysis

Vibrational analysis has been undergone to identify the vibrational modes displayed by the BH3 molecule. Furthermore, as mentioned in the optimisation section (Table 4), one can whether a minimum was achieved in the optimisation process by inspecting whether all vibrational frequencies are positive which indicates successful optimisation of the molecule (as it is in this case). Each vibrational mode has been illustrated in the table below (Table 5):

|

|

https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:KANDY3_BH3_FREQ_JESS.LOG

The table shows the major vibrational modes (6 modes) exhibited by the BH3 molecule. These highly intense peaks do not all show up as separate peak. The IR seems to show around 3 intense peaks in the IR spectrum. Firstly, the symmetric stretch will not show up on the spectrum due to the absence of a change in dipole. With the rest of the peaks, there are two sets of degenerate peaks (2 sets of E'); this explain the presence of the 3 intense peaks.

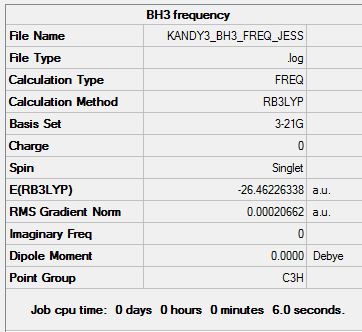

MO Diagram

In this section, the MO of BH3 will be generated using Gaussian (DFT/B3LYP method used; 6-31g basis set used- the 'full NBO tab was chosen) and this will be compared to the MO provided by Dr Hunt. The mixing that is undergone within the molecule will be illustrated in the MO diagram shown below (these were obtained from the checkpoint file generated on Gaussian):

https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:BH3_Optimisation_MO_%28kandy%29.chk

In the MO energy diagram above, the 3rd/4th MO is the the HOMO of the molecule i.e. as you move further up, unoccupied orbitals will be reached. The HOMO has a symmetry label of 1e’(doubly-degenerate). The LUMO, LUMO +1 and LUMO +2(doubly-degenerate) have a symmetry label of 1a’’2, 3a’1 and 2e’ respectively. Furthermore, the HOMO – 1 orbital (2nd MO) has a symmetry label of 2a’1.

As you move to the LUMO (5th MO) and above, the orbitals become more spread out (diffuse) compared to the orbitals located below it (1st-4th MO’s)as the orbitals are located further away from the nucleus and therefore experiences much less nuclear attraction. This diffuse nature of the LUMO is a common attribute for Lewis acids such as BH3. It is worth noting that any electron density donated into BH3 is a viable option as the non-bonding orbital (1a"2) is filled. However, any further electron donation will occupy anti-bonding orbitals causing a reduction in bond strength.

From comparing the LCAO MO diagram (provided by Dr Hunt) and the Gaussian-generated MO diagram are exactly the same. This can clearly be seen upon inspecting both the diagrams shown above. This proves that computational chemistry can be used to accurately generate MO diagrams for a variety of molecules; however, one must carefully consider which basis set should be used when dealing with a large variety of different molecules.

TlBR3 Molecule

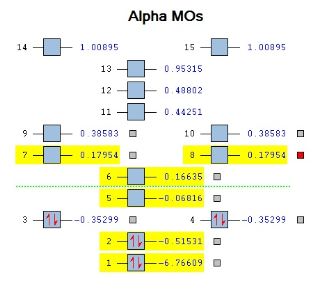

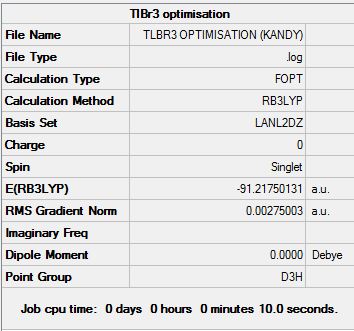

TlBR3 Optimisation

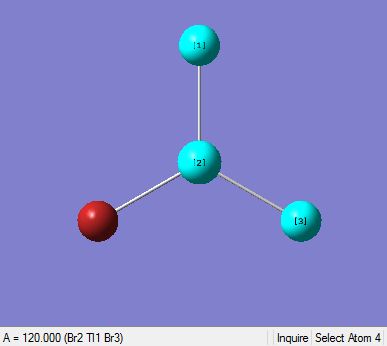

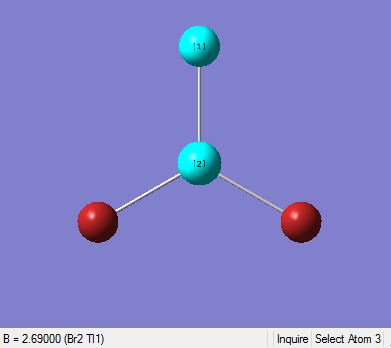

DFT and B3LYP method was used for the optimisation of BH3. However, unlike the optimisation of BH3, the basis set used for this was LanL2DZ. This is because this larger basis set only accounts for the valence electrons of the Thallium atom and neglects the rest of the metal atom’s electrons. By the use of pseudo-potentials, a faster calculation and a very accurate illustration of the molecules orbitals can be attained. The optimised structure of TlBr3 is shown below (Figure 8):

By keeping a very tight tolerance (and keeping the point group of the molecule to D3h), this enables the calculations performed to be as accurate as possible (and give us correct vibrational and NBO results).

|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000002 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000001 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000022 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000014 0.001200 YES Predicted change in Energy=-6.083881D-11 Optimization completed. -- Stationary point found.

https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Kandy3_TlBr3_freq.chk

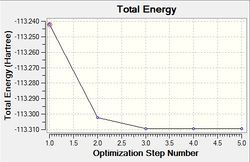

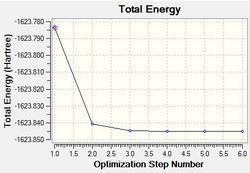

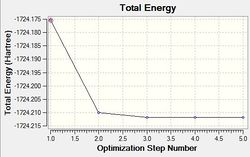

As done with BH3, the RMS and Total optimisation energy plots were obtained in order to determine whether the optimisation process was successful. Two iterations were performed and the three optimised intermediates are shown above. The optimisation can be deemed as a success as total convergence was achieved and the curve on the ‘total energy’ curve attains a gradient of zero. As explained before, you can only confirm whether a minimum (or maximum) was been achieved by looking at the vibrational frequencies. All-positive frequencies will indicate that an energy minima has been achieved. As shown on both plots, it can be seen that Intermediate 3 is the lowest in energy and therefore the optimised structure of BH3.

|

|

|

|

|

In the diagram above (Table 11), they show that the bond angle and the optimal bond distance is 120 degrees and 2.69 Angstroms respectively. The bond length is in good agreement with the literature value of 2.512 Angstroms[7]. In addition to this, the bond angle attained is 120degrees, insinuating that the optimised molecule has a trigonal planar structure.

TlBR3 Optimisation

IR Analysis

This section involves the vibrational analysis of the TlBR3 compound. The summary shown below indicates that the molecule obtained is highly optimised (this is because the RMS value indicated is very small). As alluded to before, the presence of only-positive frequencies indicate that during optimisation, an energy minima was achieved. The vibrational modes are illustrated in the tables below.

|

|

https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:TlBr3_kandy_frequency.chk

Low frequencies --- -3.4213 -0.0026 -0.0004 0.0015 3.9367 3.9367

Low frequencies --- 46.4289 46.4292 52.1449

Although some of these ‘low’ frequencies are negative, they are acceptable as they are between -5 and 0cm-1). TlBr3 will intrinsically display the same number of stretches as BH3 as they both have the same point group (D3h). The formation of three intense peaks has been explained above (see BH3 – IR frequency analysis).

what is a bond?

Throughout this project, there are several molecules that seem to have bonds ‘missing’ within the structure. However, this simple visual error is due to the inability of Gaussview to display a bond that has a distance larger than the usual ‘pre-determined’ bond length. The idea of chemical bonding helps chemists to understand the interactions of orbitals between different atoms. The distribution of electron density between these orbitals helps us understand the ‘bonding between atoms. Typically, there are three types of bonding that are exhibited by atoms/molecules[8]:

a) Covalent bonding: This involves the sharing of valence electrons between atoms in order to allow both atoms to form full (stable) octet shells.

b) Ionic bonding – This arises due to the interaction between oppositely charged atoms.

c) Metallic bonding: This type of bonding involves electrostatic interactions between the ‘sea’ of delocalised electrons and the positively charged metal cations.

Mo(CO)4L2:Cis and Trans Isomerism

Cis and Trans Isomerisation3

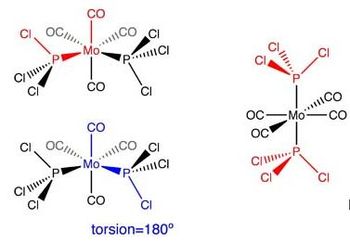

This part of the project involves the study of cis- and trans- Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2.However, Cl atoms have beenused in place of Ph groups in order to significantly reduce computational times (this substitution is allowed as they both provide similar bonding contributions). These molecules will be optimised using LanL2MB, LanL2DZ and a corrected LanL2DZ basis sets. Vibrational analysis will be used to confirm the identity of both isomers. In the case of the cis-isomer, there should be 4 carbonyl peaks present in the IR spectrum while for the trans-isomer, there should be one carbonyl peak present on the spectrum. It must be noted that the -Ph group has been substituted with Cl groups (on the Phosphorus atom) as they both have impart similar electron contributions, however, as chlorine is made up of one atom (compared to the 11 atoms on each -Ph group), it saves some computational time if Cl atom is used.

The un-optimised structures of both isomers are shown below:

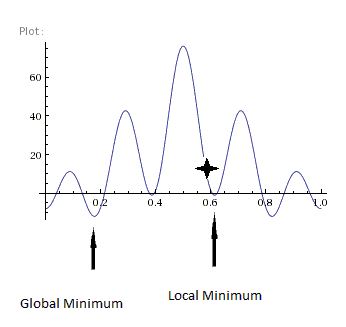

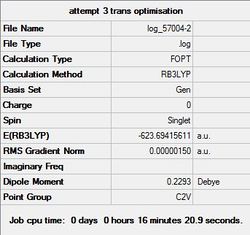

Cis and Trans Isomerisation3 Optimisation (Loose method)

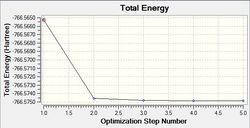

Initially, both isomers were loosely optimised using the LanL2MB pseudo potential basis set (B3LYP method). By using this method, quick but roughly optimised structures were obtained. As shown in the RMS gradient component of the summary (shown above), the very low values suggest that optimisation has occurred. However, inspection of the vibrational results is needed to confirm that an energy minimum (and not a maximum) has been achieved. As the Phosphorus groups are able to move about unhindered, this questions whether the minimum achieved is actually the lowest minimum possible(which is more likely) or just the local minimum.

The structures of the LanL2MB loosely-optimised structures can be found in the table below:

| Cis | Trans |

|

|

|

|

|

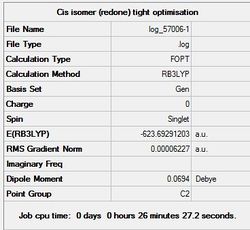

Cis and Trans Isomerisation3 Optimisation (Tight method)

After the loose optimisation of both isomers, they were then optimised ‘tightly’ using the LanL2DZ basis set. Before the optimisation was applied, the geometry of the both isomers was slightly modified:

In the case of the cis-isomer, one of the Cl points up parallel to the axial bond while a Cl (from the other PCl3 group) points down parallel to the axial bond.

In the case of the trans-isomer, both PCl3 groups were orientated so that the Hydrogen atoms eclipsed each other. For the structure of both isomers, check the table below.

By invoking these changed, computational time was reduced. Both summaries (also in the table below) show that the RMS gradient component is very low, meaning that a very optimised structure has been attained. However, one must note that the minimum achieved here may only be a local minimum (most likely scenario) rather than a global minimum.

| Cis | Trans |

|

|

|

|

|

Optional Corrected Optimisation (Tight method)

With the LanL2DZ pseudo-potential basis set, it doesn’t take into account the d-orbital interactions of the Phosphorus atom (it only takes into account the s and P orbital interactions). As a result, a correction was manually incorporated into the Gjf file in order to account for such d-orbital interactions (which are very important due to the hyper-valent structure of Phosphorus). From analysing the LanL2DZ optimised isomers and the corrected LanL2DZ optimised isomers, it can be seen that in both cases, the trans-isomer is thermodynamically more stable than the cis-isomer.

| Cis | Trans |

|

|

|

|

|

| Bond | Tight Optimisation(LanL2DZ)

Bond Length [Å] |

dAOs Modified Optimisation (LanL2DZ)

Bond Length [Å] |

Literature Value [Å][10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-C (axial) | 2.01 | 2.02 | 1.98 |

| Mo-C (equatorial) | 2.06 | 2.06 | 2.02 |

| C-O | 1.18 | 1.17 | 1.21 |

| Mo-P | 1.18 | 1.18 | 2.56 |

| Bond | Tight Optimisation(LanL2DZ)

Bond Length [Å] |

dAOs Modified Optimisation (LanL2DZ)

Bond Length [Å] |

Literature Value [Å][11] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-C | 2.06 | 2.05 | 1.85 |

| C-O | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.16 |

| Mo-P | 2.44 | 2.42 | 2.50 |

Frequency Analysis of optimised Cis-Isomer

From inspecting both graphs, it can be seen that both sets of results are both similar. However, the accuracy of both sets of data will be compared to literature values in order to determine whether the dAO modification has helped improved the accuracy of the calculation.

| Cis | Trans |

|

|

|

|

|

The vibrational modes of the Cis-isomer are described in the table below:

| Mode Number | Movie File | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Frequency (cm-1) (dAO correction)[literature [12] | Intensity (dAO correction) | Group | Symmetry |

| 1 |  |

2023 | 596 | 2019[2026 ] | 545 | C=O | A1 |

| 2 |  |

1958 | 634 | 1952[1924] | 588 | C=O | A1 |

| 3 |  |

1948 | 1498 | 1941[1896] | 813 | C=O | B1 |

| 4 |  |

1945 | 762 | 1938[1869] | 1605 | C=O | B2 |

| 5 |  |

18 | 0 | 20[no lit. value] | 0 | PCl3 | Bend |

| 6 |  |

11 | 0 | 12[no lit. value] | 0 | PCl3 | Bend |

The IR spectrum of the cis-isomer (LanL2DZ and modified LanL2DZ basis sets) shows the presence of 4 intense carbonyl stretches; this is in accordance with general intuition. This is because each of the 4 carbonyl vibration modes are slightly asymmetric hence peaks will arise as a result of this observed dipole movement. The vibrational values calculated using the LanL2DZ and modified LanL2DZ basis sets were very similar.

Frequency Analysis of optimised Trans-Isomer

| Cis | Trans |

|

|

|

|

|

The vibrational modes for the Trans-isomer are described in the table below:

| Mode Number | Movie File | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Frequency (cm-1)(dAO correction)[Literature[13]] | Intensity (dAO correction) | Description | Symmetry |

| 1 |  |

2031 | 4 | 211 [2050 ] | 25 | C=O | A1g |

| 2 |  |

1978 | 1 | 211 [1933] | 25 | C=O | B1g |

| 3 |  |

1951 | 1467 | 165[1885] | 0 | C=O | Eu |

| 4 |  |

1950 | 1475 | 52[1865] | 6 | C=O | Eu |

| 5 |  |

6 | 0 | 46[no lit. value] | 4 | PCl3 | Bend |

| 6 |  |

5 | 0 | 46[no lit. value] | 4 | PCl3 | Bend |

In the case of the trans-isomer, one would expect only one peak to show up on the observed IR spectrum and this observation is seen in the Gaussian-calculated IR spectrums. The reason for the presence of one carbonyl vibrational band is due to two reasons:

a) The A1g and B1g vibrational modes only experience an incredibly small change in dipole moment as the stretches involved are nearly-perfectly symmetrical. This means the vibrational modes are not completely IR inactive but instead, there are very small peaks (of very weak intensity) present in the IR spectrum which are hard to see.

b) Two of the asymmetric carbonyl stretches are degenerate therefore only one peak (of high intensity due to the large change in dipole) will appear on the IR spectrum. Once again, the vibrational results obtained for the LanL2DZ and modified LanL2DZ basis sets are very similar, however, in this case, modified LanL2DZ basis set provides a slightly more accurate set of results (when compared to the literature values).

The very low/slightly negative frequencies obtained for are thermally excited at ambient temperature. In addition to this, the cis and trans isomers may be able to interconvert readily due to the very similar energies of the isomers.

Mini Project

Introduction

The purpose of this mini-project is to explore the extent of π back-bonding in metal hexa-carbonyls (with the same number of valence electrons). Two different basis sets will be compared and contrasted (while DFT will be used throughout the project; the 6-31g (full electron) basis set and the 6-311g (full electron/pseudo potential) basis set will be used in order to calculate the distribution of electron density within the molecule.

IR analysis can be used to great effect when trying to determine the amount of π back-bonding within the complex. By looking at the vibrational frequency of the metal-Carbon bond as well as the Carbonyl bond, the strength of the bond can be deduced. By comparing the complex’s carbonyl bond to the length of the C-O bond in carbon monoxide, one can determine the extent of back-bonding within a molecule.

First of all, let us delve into the basic concept of (π) back-bonding within metal complexes:

The metal and the carbon atom (of the carbonyl ligand) are principally bonded via a σ bond (which occurs from the ligand and towards the metal centre). In addition to this, if there is a sufficient amount of electron density in the d orbital of the metal centre, some of this electron density is donated by the metal into the π* CO antibonding orbital i.e. the strength of the Metal – Carbon bond is increased (synergistic relationship) while the bond strength of the Carbon-Oxygen bond decreases, leading to the lengthening of the C-O bond. Hence, the more electron-rich a metal centre is, the weaker the carbonyl bond of that particular metal hexa-carbonyl complex. The overall process is shown below:

IR analysis could be used to provide us with the relative bond strength of the C-O ligand bonds i.e. one would imagine that the more electronegative the metal centre of the hexa-carbonyl complex is, the greater the back bonding ; this leads to the IR spectrum displaying a C-O band of a lower wavenumber than that of free C=O or hexa-carbonyl complexes with an electron-deficient metal centre.

THe back-bonding in VCO6- ,CrCO6 and MnCO6+ will be compared using various analysis such as IR and NBO analysis in order to illustrate the points made above.

Molecules

| CO | VCO6- | CrCO6 | MnCO6+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimisation

As mentioned previously, two basis sets were used for the optimisation of each complex. Each complex was (separately) optimised using the DFT method/ 6-31g (full electron) basis set and the DFT method/6-311g and LanL2DZ (full electron/pseudo potential mix) basis set.

In the case of CO, it is necessary to optimise the geometry of the molecule using the 6-31g(although 3-21g can also be used). As orbitals vary in size, it is essential that this variation in size is taken into account. The advantage of using 6-31g is that more than one basis function is provided, allowing for a better fit in terms of size of the orbital (as opposed to a different shape). Furthermore, in the case of CO, the use of this basis set is fairly cheap and computational time is fairly low.

AS indicated in both summaries, there is a dipole charge present in the molecule. This is due to the electronegativity difference between the highly electronegative oxygen atom and the electropositive carbon atom.

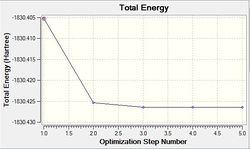

By looking at the summary for both basis sets, it can be seen that the RMS gradient is much lower (by a factor of 2) for the 6-31g optimised CO molecule compared to the 6-311g/LanL2DZ optimised CO molecule. This indicates that the 6-31g basis set produced the lowest energy optimised structure. In both cases, total convergence occurred and a zero gradient was achieved (for the first derivative)confirming that optimisation had succeeded.

In addition to this, the same results were obtained for the following three metal complexes (barring the dipole charge which is zero for all three complexes).

Vibrational analysis

| Basis set | Product 1 | Product 2 | Product 3 | Product 4 |

| 6-31g |  |

|

|

|

| 6-311g |  |

|

|

|

- Intensities are denoted within [...] as shown above

From looking at the IR spectrums shown above, it is evident that there are no C=O stretches present on them. Upon analysis of the vibrational modes, it can be seen that for each molecule, each C=O vibrational mode incurs no change in dipole moment; i.e. as the symmetry of the molecule is kept intact, no IR band arises.

In terms of backbonding, one can see that a pattern emerged for each individual vibrational mode. In the case of the first vibrational mode (where all bonds stretch in phase), the wavenumber of the C=O stretch for the Cr complex is around 90cm-1 larger than that in the V(-I) complex. As you then moved from the Cr hexacarbonyl complex to the Mn(I) hexacarbonyl complex, the wavenumber of the C=O stretch increased by 90cm-1. This trend is evident for each vibrational mode. As explained in the introduction, this occurs due to the following reason: As you move from left to right (V(-I) complex - Cr complex - Mn(I) complex), the amount of electron density in the metal central atom decreases; intrinsically, this means that less electron density is donated into the empty C-O π* orbital. This results in a stronger C=O bond which is evident on the IR spectrum in terms of a higher wavenumber. Furthermore, it results in a stronger Metal-Carbon bond.

It is essential to compare the values generated by the use of different basis sets (note: all calculations were run using the DFT/B3LYP method). In the case of the V(-I), Cr and Mn(I) complexes,the literature value for the most intense C=O peak wavenumber are 1860,2000 and 2090cm-1 respectively. The presence of only one C=O peak is due to the highly symmetrical nature of the homoleptic molecules in question. Surprisingly, the 6-31g basis set helped produce better results in comparison to the 6-311g/LanL2DZ basis set (which was used in this mini-project as it is a suitable option when dealing with heavy atoms such as Mn, Cr and V atoms. Furthermore, it is known that with such heavier metals, the 6-31g basis set is usually generates moderately unreliable results (due to the absence of any sort of diffusion component). However, literature suggests that medium -sized basis sets such as 6-31g overcompensates values due to the basis set neglecting electron correlation (~15%)

NBO

| Free CO | V complex | Cr complex | Mn complex |

|

|

|

|

For NBO analysis, the 3 complexes were optimised using the DFT/B3LYP method and the 6-31g basis set was used. In addition to this, the three complexes were also optimised using the DFT/B3LYP method and the 6-311g/ LanL2DZ method was used (as it should give a much more accurate depiction of the relevant MO’s and give satisfactory stabilisation energy values for each complex). After severe problems, the molecule was re-optimised using the same method and then NBO analysis was undergone where the ‘custom’ option on the basis set option was set (and the energy calculation was undergone).

From charge distribution analysis, one can see the increase in the amount of π-back bonding (into the empty C-O π* orbital) as you move from Mn(-I) to Cr and then to V(I). Moving from left to right, the metal atoms have a lower amount of electron distribution localised on the metal atom, therefore this means that less electron density is transferred to the Carbon and Oxygen atoms.

The values above illustrate the secondary orbital interaction. The pi back bonding can be observed and proved using data obtained in these calculations. It shows the donor/acceptor interactions; using the 6-31g basis set, the stabilisation energy obtained for the V (charged complex), Cr complex and the Mn (charged) complex is 55.19 kcal/mol, 25kcal/mol and 14.91 kcal/mol respectively (this shows the stabilisation energy between the lone pair on the metal centre that is donated into the C-O π* orbital. This can be explained as follows: The strength of the back-bonding increases as the electron density decreases as you move from V(I) to Mn(-I). Despite having the same number of electrons, the higher electron/proton ratio makes the V(I) complex the most electron dense complex, therefore electrons can be donated to a greater extent. This leads to a greater stabilisation energy.

The second set of results have not been analysed as no basis set could be applied (especially pseudo-potential) without error. However, the results have been displayed to show that some measures were taken to try and obtain NBO data usingthis particular basis set.

In the case of the V(I) complex, the V-C bond has a electron distribution of 26%:74% meaning a large portion of the metal electron density has been donated into other orbitals (π* c-O orbital). In the Cr complex and the Mn complex, the ratio of electron distribution in the Metal-Carbon bond is 27%:73% and 31%:69% respectively.

In addition to this, the values above also show that there is 33% d component in the V(I)complex, indicating that some π back-bonding is occurring from the occupied d orbital of the metal into the π* c-O orbital. This d component is also seen in the other two complexes confirming that all the complexes undergo π* c-O orbital back-bonding.

Furthermore, in all the complexes, there is data that shows the formation of π bonds. The Oxygen atom and the Carbon atom have sp2 orbitals that overlap to form a sigma bond. In addition to this, each of these atoms have pure p-component (100%) that overlap to form the π bond.

MO

In the case of the 6-31g basis set (using the B3LYP/DFT method), the LUMO +1 orbitals and the HOMO+1 for all the complexes look very similar. However, there are few differences between some of the orbitals in the HOMO and LUMO.

In the LUMO of the Cr complex and the Mn complex, the orbitals look nearly-identical. The V complex produces an orbital that looks slightly different. In particular, there is no interaction between the carbon atoms of different carbonyl ligand with each other. In the other compounds, all the carbon atoms of individual carbonyl ligands seem to interact with each other. The orbitals involved in the LUMO is the sigma* orbital in the case of the Vanadium complex (as opposed to the Pi* orbitals of the other two complexes).

The HOMO orbitals for each complex all look very similar (6-31g method).

It is hard to interpret the MO diagrams and even more difficult to form a conclusion regarding the presence of back-bonding in the complex.

Further analysis will be undergone to describe the orbitals present in each complex (however, in this case, Cr complex will be analysed):

Conclusion

This mini-project has used many different techniques successfully in order to determine the extent of π back-bonding. Although MO analysis was used was touched upon, IR and NBO analysis was used extensively in order to establish whether a change in electron density on the metal affected the strength of the co-ordinated carbonyl bond. Overall, it has been established that computationally calculated results tend to mirror literature values, justifying why such methods are becoming even more popular in the scientific community.

References

- ↑ Peter Atkins, Julio de Paula, Atkins' Physical chemistry 8th edition, Oxford University press 2006, pp360-365

- ↑ Guy Grant,Graham Richards, Computational Chemistry, Oxford Science Publications, 1995,

- ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:BH3_Optimisation_MO_%28kandy%29.chk

- ↑ Schuurman et al.,Journal of Computational chemistry, 2005, 26,11

- ↑ Molecular Geometry and Hybrid Orbitals Module,Department of Chemistry, UCLA

- ↑ Dr Patricia Hunt, MO diagram of BH3 (Lecture 8), Molecular Orbitals in Inorganic Chemistry Module, Department of Chemistry, Imperial College London

- ↑ Glaser,Johansson, Acta Chemica Scandinavica A 36 (1982) 125-135

- ↑ H.B.Gray,Chemical bonds: an introduction to atomic and molecular structure,1994

- ↑ Dr Patricia Hunt Research Group: www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/10b_MoC4L2_opt.html (12/03/12 15.49)

- ↑ Cotton, Darensbourg, Klein, Kolthammer,; Inorganic chemistry, 1982, 21, 295

- ↑ Cotton, Darensbourg, Klein, Kolthammer,; Inorganic chemistry, 1982, 21, 295

- ↑ Ardon,Hayes. Hogarth, Journal of Chemical Education 79(10), 1249-12511

- ↑ Darensbourg,D.J.,Inorg. Chem, 1979, 18, 14-17.

- ↑ Dr Wilton Ely, Advanced Organometallics Module, Lecture 1, Department of Chemistry, Imperial College London