Rep:Mod:jelliclecats2

Part I: Basics

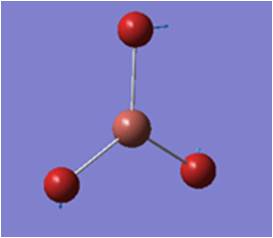

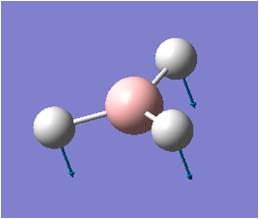

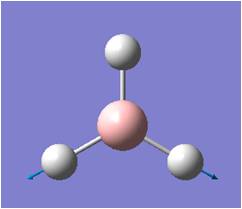

BH3

Optimisation

BH3 is optimised using Gaussian, with the method used being B3LYP and basis set of 3-21G, a relatively simple basis set. A "simple" basis set, when applied to large or complicated complexes/molecules/atoms will result in larger inaccuracies and errors during calculation; however, it is applied here as BH3 is a relatively small and symmetry molecule, and its calculation accuracy is not compromised. A summary of the optimisation is shown:

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | 3-21G |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | singlet |

| E(RB+HF-LYP) | -226.4622 a.u (600670 kJ/mol) |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.00 Debye |

| Point Group | D3H |

| Job cpu time | 10.0 sec |

| B-H Bond length | 1.19Å |

| HBH Bond angle | 120.0° |

As can be seen here, the optimised bond length is 1.19Å while the bond angle is 120.0°, corresponding well with theoretical and experimental observation that BH3 adopts a trigonal planar structure of bond length 1.21Å and bond angle 120.0° [1].

BH3 optimisation log file output: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/a/a0/Leyang_BH3_OPT.LOG

Vibrational Analysis

On the optimised BH3 molecule, a frequency analysis was performed:

Logfile output to be accessed here: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/a/a7/BH3_FREQ_LE_YANG.LOG

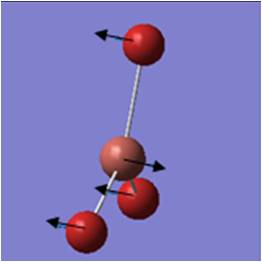

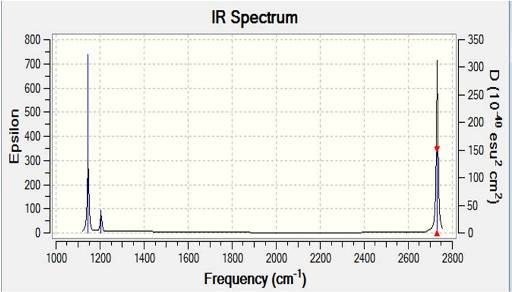

| No. | Mode of Vibration | Description | Freq/cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry (D3h) | Literature Freq /cm-1[2] |

| 1 |  |

Out of plane wagging: All H move in direction of arrow while B moves slightly in exactly the opposite direction. | 1146 | 93 | A2" | 1159 |

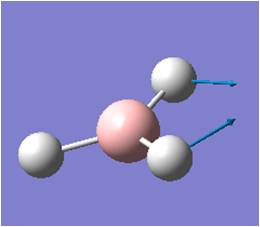

| 2 |  |

In-plane Scissoring: 2 H move in criss-cross fashion (scissors-like) while B moves slightly in opposite direction, away from the 2H's. Third H does not move. | 1205 | 12 | E' | 1202 |

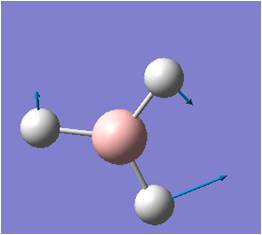

| 3 |  |

In-plane Rocking: 2H and B rock concertedly in plane as one unit, while the third H rocks in opposite direction with larger amplitude. | 1205 | 12 | E' | 1202 |

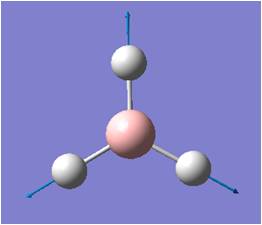

| 4 |  |

Symmetric Stretching: All three H move away (or towards) B in the BH3 plane, while B remains unmoved. | 2593 | 0 | A1' | NA |

| 5 |  |

Asymmetric stretching: two H move in opposite directions with B wagging in the plane of the screen, while the third H remains unmoved. | 2731 | 104 | E' | 2616 |

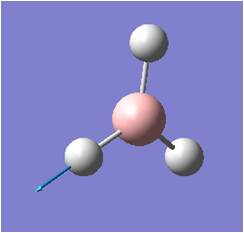

| 6 |  |

Asymmetric stretching: two H move away (or toward) B in concerted motion, while third H moves towards (or in -- opposite to the two H), all in the plane of screen. B moves towards and away from this third H. | 2731 | 104 | E' | 2616 |

6 IR peaks are predicted according to the table shown above, but only 5 peaks are seen both experimentally and in the IR spectrum above. This is because the 4th vibration mode, symmetric stretch, where all three H's move in and out at the same time while central B remains stationary, has a change in dipole moment of zero as the dipoles moments of individual stretches cancel each other out. Since IR detects the changes in dipole moment of a certain vibrational mode, the resultant intensity is zero, and hence not reflected on the spectrum. It does not mean this form of vibration is non-existent.

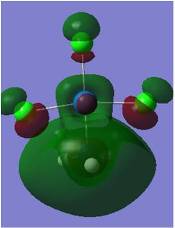

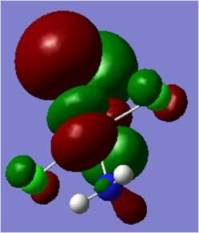

Population Analysis (MO)

Data for MO/NBO (Energy) of BH3 :DOI:10042/to-5888

Referring to Dr Patricia's Hunt lecture notes and tutorial from Year 2(2009-10), the molecular orbital (MO) diagram for BH3 is reproduced here (with ChemDraw 12.0) with modifications, based on MO Theory:

It is seen that the MO diagrams and their relative energy levels produced from Gaussian calculations match reasonably well with that predicted by MO theory. The shapes, phases, and electron density/distribution of these two sets of results are in good agreement. Their relative energy levels match rather well, with the exception of the top two energy levels -- orbitals 3a1' and 2e'. In MO theory, the prediction gave 2e' orbitals being higher in energy than 3a1' orbotal, while Gaussian results in the opposite situation. This is an inherent limitation of the MO theory, where the exact energy of the orbitals cannot be determined, hence producing an uncertainty of the order of energy levels, especially when two non-degenerate MOs are close in energy and cannot be determined by mere pictorial representation. The situation is complicated with MO mixing (not present in this case) where difficulties in determining the order of energy levels might be tricky. But generally, Gaussian calculations and MO theory gave similar predictions and Gaussian can be used as a reliable source of prediction.

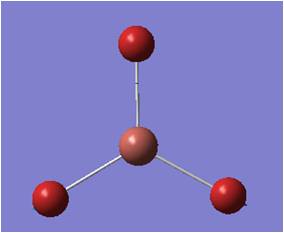

TlBr3

Optimisation

TlBr3 is optimised by Gaussian, using B3LYP method with a pseudo potential applied (LanL2DZ) due to heavy atoms being present that need a higher level of basis set than the simpler 6-311G(d,p) model.

Log file output to be accessed here: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/8/83/LEYANG_TLBR3_OPT.LOG

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | single |

| E(RB+HF-LYP) | - 91.2181 a.u (241947 kJ/mol) |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.00 Debye |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Job cpu time | 11.0 sec |

| Tl-Br bond length | 2.65Å |

| Br-Tl-Br angle | 120.0° |

Bond length reported in literature[3] is 2.52Å and bond angle is 120.0Å, which is in reasonable agreement with calculated values obtained here, obeying the ideal geometry of a trigonal planar compound. The slight deviation could be accounted for by simulated conditions done by Gaussian being different from the method of measurement done experimentally.

After optimisation, it is checked that the geometry of the compound has all converged, and that its energy has fallen to a minimum as shown by the graphs below. When optimised, the energy of the structure should be the lowest possible, where optimal bond distances are achieved at which the positive potential energy generated by nuclear repulsion is balanced by the negative potential energy generated by nuclear-electron attraction.

Vibrational Frequency Analysis

Frequency .log output file to be accessed here: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/c/cd/TLBR3_FREQ_LEYANG.LOG

As seen from the graphs above, the gradient of the energy graph has reached nearly zero, though it cannot be determined if this is a minimum or maximum. So a second derivative calculation is carried out, in terms of frequency analysis -- where all values obtained need to be positive in order to confirm a minimum turning point. Any negative second derivative values would mean maximum being present, and thus optimisation has not been successfully achieved since a minimum energy is not obtained.

Vibration frequency analysis is done using the same method and basis set, upon the optimised structure obtained after optimisation. It is necessary to use the same method and basis set to ensure accuracy and consistency of results obtained. Frequency essentially is the second derivative of energy optimisation optimisation; if the method or basis set is changed subsequently for frequency calculation, it is apparent that the second derivative values would then not reflect what has been initially calculated.

- Low frequencies reported for this calculations are reported to be:

-3.4226 -0.0026 -0.0004 0.0015 3.9361 3.9361 - Real low frequencies actually start at:

46.4288 46.4291 52.1449 - These values are quoted from log file without altering their decimal places.

IR frequencies and their vibration modes are shown in the table below, together with literature values for comparison, and followed by an overview of IR spectrum:

For symmetrical molecules, 3N-6 vibrational modes should be present, where N is the number of atoms. For non-symmetrical molecule, 3N-5 vibrational modes should be seen. Therefore, for both BH3 and TlBr3 symmetrical compounds, 6 vibrational modes should be observed, corresponding to Gaussian calculated results.

Bond

- No bonds drawn in Gaussview? Does it mean there is no bond?

No, it does not mean there is no bond even if there isn't one drawn between two atoms. Gaussview, working from a pre-defined set of definitions, criteria and paramters, has a pre-assigned minimum value for bond length in order for a 'bond' to be recognized as a 'bond' with the bond drawn. This usually works fine for organic compounds whose bond distances are within predicted or pre-determined range. For inorganic compounds, the internal list of bond distance within Gaussview is not exhaustive anymore and often bond lengths are longer than those found in organic molecules, resulting in Gaussview not recognizing it as a bond and thus no bonds are drawn in. But the interactions are certainly present.

- What is a bond?

A chemical bond is an interaction between atoms or molecules which results in the formation of polyatomic compounds. Bonds can be categorized in terms of ionic, covalent, dipole-dipole and hydrogen-bonding. In other words, it is the electrostatic forces of attraction between opposing charges, either between electrons and nuclei, or a result of dipole moments.

Part II: Organometallic Complex

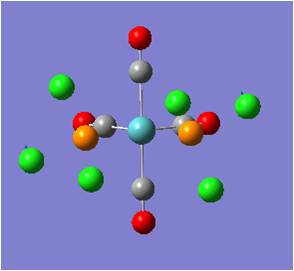

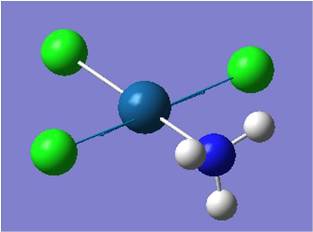

Mo(CO)2(PCl3)2 Cis-Trans Isomerism

Optimisation

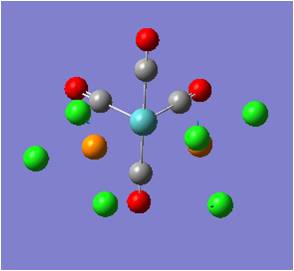

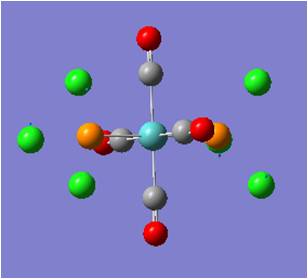

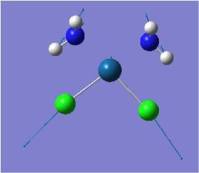

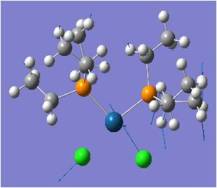

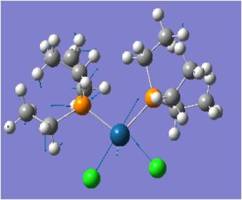

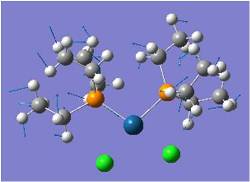

The cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 are optimised by the method B3LYP in Gaussian, first pre-optimised the pseudo potential/basis set LanL2MB to get close to the structure with the minimal energy (opt=loose), and subsequently optimised a second time with the pseudo potential LanL2DZ. Pseudo potentials are applied here to provide a higher level of optimisation for these heavier atoms. LanL2DZ is an even higher level optimisation than LanL2MB, more suited to this large complex with heavy atoms like Mo.

| (1st optimisation) | ||

| cis-isomer | trans-isomer | |

| Jmol | ||

| D-space link | DOI:10042/to-5887 | DOI:10042/to-5886 |

| File Type | .log | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2MB | LANL2MB |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | singlet | singlet |

| E(RB+HF-LYP) | - 617.5252 au (1637923 kJ/mol) | - 617.5221 au (1637915 kJ/mol) |

| Dipole Moment | 8.62 | 0.28 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 8min 42.6sec | 8min 50.7sec |

| (2nd optimisation) | ||

| D-space link | DOI:10042/to-5884 | DOI:10042/to-5885 |

| File Type | .log | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2DZ | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | singlet | singlet |

| E(RB+HF-LYP) | -623.5771 a.u. (1653976 kJ/mol) | -623.5760 a.u. (1653973 kJ/mol) |

| Dipole Moment | 1.31 | 0.30 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 22min 13.9sec | 40min 20.5sec |

Jugding from their optimised energies, it can be concluded that trans-isomer is slightly more stable by ~3kJ/mol, though a minimal margin. This is probably due to two reasons:

- Sterically bulky PCl3 (or PPh3, even bulkier) are separated further apart in trans-isomer, relieving steric strain.

- Due to the geometrical arrangement of the groups, the dipole moments of each group of substituents cancel out, resulting in overall dipole moment of zero, again stabilising the complex.

This fact that trans-isomer being more stable is echoed by literature[4], where trans-[PtCl2(PPh3)2] is the thermodynamic product while the cis-[PtCl2(PPh3)2] is the kinetic product. Experimentally, this is told through reaction time required to form trans-product being longer than time required to form cis-product[5].

Inferring from the two reasons of stabilisation above, it can be hypothesized that, to further stabilise trans-isomer, we can:

- Use more bulky PL3 ligand, eg PPh3. This destabilises cis-isomer to a far larger extent due to heavy steric clash. The steric relief can be seen more significantly on trans-isomer.

- Use a more electronegative group than PL3, eg use Fluoride instead. This produces a more significant effect on the dipoles. The cancellation of dipole moment in trans-isomer is more significantly observed as compared to cis-isomer (which will have a larger dipole moment), and stabilisation will be more apparent.

Critical bond lengths and bond angles of trans-isomer is compared with literature (with PPh3 instead of PCl3 ligands)[6]:

| Gaussian | Literature[7] | |

| Mo-P/Å | 2.44 | 2.5 |

| Mo-C/Å | 2.06 | 2.005 |

| P-Cl (P-C in lit)/Å | 2.24 | 1.828 |

| C-O/Å | 1.17 | 1.164 |

| P-Mo-P/° | 177.4 | 180 |

| trans-C-Mo-C/° | 179 | 180 |

| 180 | ||

| cis-C-Mo-C/° | 89.5 | 92.1 |

| 90.5 | ||

| P-Mo-C/° | 91.3 | 87.2 |

| 90 | ||

| 88.7 |

Generally, the results produced by Gaussian are in close range with experimental observation -- however the bond lengths/angles for equatorial and axial positions seem to be different in the Gaussian optimisation, unlike the uniform values reported in literature, though it is noted that the deviations are small. This means that the optimisation did not produce what the complex is like in reality. Perhaps another method and basis set or pseudo potential could be used to produce a more accurate prediction. Generally, it is still a reliable modelling as the bond lengths and angles are within close range with real values. It could also mean that literature reports an averaged measurement but did not specify it, as it is only logical that due to the steric strain posed by the bulky PPh3 ligand that the geometry distorts from the ideal octahedral structure.

Vibrational Frequency: Low Frequencies

Data for IR analysis of Cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 :DOI:10042/to-5883

Data for IR analysis of trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 :DOI:10042/to-5829

These vibrations occur at low frequencies, i.e. only low energies are required to incur the vibrations (since energy is proportional to frequency, by the relationship E=hf), possible even at room temperature. From low energy vibrations, it can be inferred that the energy gaps between these vibronic levels are small.

Vibrational Frequency: C=O Stretches

Carbonyl stretches from Gaussian calculations are compared with literature experimental values[8]:

| Gaussian IR Frequency /cm-1 | Computed Intensity | Literature IR Freq/cm-1[8]

|

Symmetry |

| 1945 | 762 | 1986 | B2 |

| 1949 | 1500 | 1994 | B1 |

| 1958 | 635 | 2004 | A1

|

| 2023 | 596 | 2072 | A1 |

| Gaussian IR Frequency /cm-1 | Computed Intensity | Literature IR Freq/cm-1[8]

|

Symmetry |

| 1950 | 1476 | 1896 | Eu |

| 1951 | 1467 | 1896 | Eu |

| 1977 | 1 | NA | B1g |

| 2031 | 4 | NA | A1g |

For cis-isomer, the number of peaks obtained and the frequencies at which they occur match with literature data. All four modes of vibrations are IR-active due to the presence of overall change in dipole moment. However, for trans-isomer, only two peaks are observed experimentally while four peaks are predicted by theoretical calculation. The two Eu peaks match well in value with literature. The other two vibration modes, however, are not IR active as they do not possess an overall change in dipole moment, explaining the absence of these two peaks on spectrum (intensity = 0) Again, this does not mean the IR-inactive modes are not present; Gaussian calculations allow viewing of non-observeable forms of vibrations.

Part III: Mini Project

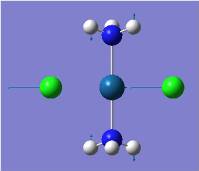

Introduction: Trans Effect of Square-Planar Pt(II) Complexes

Trans effect is the ability of ligands to become labile, in inorganic chemistry, in relationship to certain other ligands trans to themselves, thus forming trans-directing effect when considering reactions like nucleophilic substitution, where the incoming ligand only substitute at certain positions due to trans effects exerted by existing ligands on the metal centre. This observation has two aspects to it[9][10]:

- Kinetic trans effect. This is empirically observed on rates of substitution by trying out with a series of common ligands. It acts by supposedly lowering the energy of the transition state (or reducing the activation barrier) thereby stabilising it towards the kinetic product. It is also observed from the results that the kinetic trans effect is proportional to the σ-donation ability of the trans-ligand.

- Thermodynatic or structural trans influence. It is concluded that the σ-donation strength of a ligand is closely related to the bond length of the leaving ligand.

These two sets of factors work together and the resulting order of trans-effect or trans-directing ligands are observed to coincide; in fact the two sets are influences are sometimes inter-dependent. The sequence is best reflected on Pt(II) complexes, which are d8 and usually adopt a square planar geometry (though it is to be noted that octahedral trans-effect on Pt(II) is widely observed too).[9] The commonly accepted series is as follows, in order of increasing intensity of trans effect[10]:

F-, H2O, OH- < NH3 < py < Cl- < Br- < I-, SCN-, NO2-, SC(NH2)2, Ph- < SO32- < PR3, AsR3, SR2, CH3- < H-, NO, CO, CN-, C2H4 (For this report, no π-donor ligands are considered or discussed.)

σ-donation ability of a ligand depends on the σ-donation strength of the ligand trans to it, and hence, trans effect caused by σ-donation is essentially a competition between trans ligands for the opportunity to donate electron density to the central Pt(II) atom.[9] In other words, the above ordering of trans-activating ligands is in fact an ordering of nucleophilicity towards Pt(II) -- the better the nucleophile, the stronger the trans effect.

The project is divided into two main parts:

- A trans-directing nucleophilic substitution is investigated:

[PtCl3(NH3)]- + NH3 --> cis-PtCl2(NH3)2 OR trans-PtCl2(NH3)2 + Cl-

It has been widely shown that the cis-product, or cisplatin (famous for its anti-tumour properties in anti-cancer drug therapy), is formed preferentially to its trans-counterpart. Computational methods will be used to try to predict or verify this experimental observation, mostly in terms of bond strength.

- Substitution of ligands on cisplatin is then investigated, based on two fats:

- Strong σ-donors 'T' (eg PR3) weaken the Pt-L bond trans to itself: so NH3 ligands are replaced with PEt3 which are better donors to see the effect on Pt-Cl bonds.

- A more electronegative ligand 'T', the more Pt-T molecular orbital swells, and thus depleting electron density between Pt-L (where L is the leaving ligand): so Br- replaces Cl- ligands, where Br, though being less electronegative than Cl-, is a stronger donor than Cl-(higher up the trans-activating order than Cl-), and thus again it weakens the Pt-N bond trans to itself.

It follows that with very strong σ-donors, the leaving ligand L most likely gets substituted via a Dissociative or dissociatively activated interchange (Id) mechanism, since Pt-L is very much weakened[9].

However, it is to be noted that these sets of 'rules' are only based on observation, and forms a rationalised justification or generalisation, i.e. not absolute.[10]

Optimisation

All optimisation and subsequent analyses (vibrational frequency, natural bond orbital/population analysis) are performed by Gaussian, with a method of B3LYP and pseudo potential basis set LanL2DZ, applied to all complexes and molecules used in this project. Applying the same conditions for all compounds is necessary, as the energy generated by optimisation is very 'subjective', very much dependent on the method/basis set used and may churn out vastly different numbers. Using the same conditions will provide some form of consistency for comparison, where needed. Using the same method/basis set for all analyses of the same compound is also critical as it will continue to work on the already-optimised structure, providing accuracy and consistency.

Pseudo potentials are used in this case, as heavy atom Pt requires more than a simple level of modelling. An alternative way of performing these calculation is by applying the pseudo potential (LanL2DZ) only to Pt while a simpler basis set (eg 6-311G(d)) on other atoms.

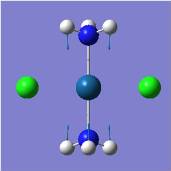

| [PtCl3(NH3)]- | cis-PtCl2(NH3)2 | trans-PtCl2(NH3)2 | cis-PtCl2(PEt3)2 | cis-PtBr2(NH3)2 | |

| Compound No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| D-space link | DOI:10042/to-5813 | DOI:10042/to-5827 | DOI:10042/to-5826 | DOI:10042/to-5828 | DOI:10042/to-5815 |

| Jmol | |||||

| File type | .log | .log | .log | .log | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LanL2DZ | LanL2DZ | LanL2DZ | LanL2DZ | LanL2DZ |

| Charge | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | singlet | singlet | singlet | singlet | singlet |

| E(RB3LYP)/a.u | -220.7929 | -262.2982 | -262.3216 | -637.4663 | -258.738 |

| E(RB3LYP)/kJ mol-1 | -585631 | -695720 | -695782 | -1690816 | -686277 |

| Dipole moment | 8.23 | 1.72 | 0.00 | 13.15 | 11.65 |

| Point group | C1 | C1 | C1 | C1 | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 2min 35.3sec | 18min 26.9sec | 2min 36.9sec | 3h 47min 37.2sec | 17min 28.9sec |

| NH3 | Cl- | |

| D-Space link | DOI:10042/to-5821 | DOI:10042/to-5825 |

| File type | .log | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LanL2DZ | LanL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | singlet | singlet |

| E(RB3LYP)/a.u | -56.5483 | -14.9986 |

| E(RB3LYP)/kJ mol-1 | -149989 | -39782 |

| Dipole moment | 1.20 | 0.00 |

| Point group | C3v | Oh |

| Job cpu time | 27.0sec | 4.6sec |

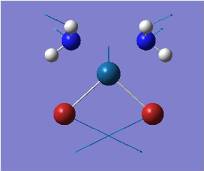

Investigating Reaction: Focus on [PtCl3(NH3)]-

In terms of energetics, the sum of energy of starting materials is compared with the sum of energy of possible combinations of products. It can be seen that the overall reaction is endothermic, with the trans-product 3 being slightly more thermodynamically stable by nearly 60kJ/mol. It can be inferred that the cis-product 2 could be the kinetic product, with lowered activation barrier. Trans isomers are generally more stable, as seen from Part II of this module, as it is stabilised both by steric relief and overall zero dipole moment. Judging from energies alone, no meaningful conclusions can be drawn regarding observed selectivity.

Taking trans-effect into consideration, Cl- being a stronger nucleophile and donor than NH3, it is higher up the trans-directing series, and thus weakens the Pt-N bond trans to Cl-. Hence, there are two possible positions for substitution -- either NH3 or a Cl- cis to NH3 gets kicked out: NH3 is trans to a Cl, so Pt-N bond is potentially weakened; the two Cl's are trans to each other, potentially weakening each other in turn. Therefore, bond strengths of various Pt-Cl and Pt-N bonds are looked into with the following analysis, anticipating the leaving Pt-Cl bond to weakened:

- Bond lengths: stronger bond results in shorter length

- IR: vibration frequency is proportional to energy of bond. Thus, higher frequency correlates to a stronger bond

- NBO/Charge distribution: larger the charge difference, more polar the bond, hence stronger the bond. Bonding interaction energies can be intepreted as stability and strength of bond too -- the more negative, the stronger.

Mechanism-wise it is difficult to determine for certain the mechanistic pathway the reaction undertakes.[11]

Bond Lengths & Angles

For convenience, the two Cl ligands cis to NH3 will be referred to as Cl'.

| Gaussian | Literature[12] | |

| Pt-Cl (trans to NH3)/Å | 2.41 | 2.317 |

| Pt-Cl' (cis to NH3)/Å | 2.46 | 2.29 |

| Pt-N/Å | 2.09 | 2.06 |

| N-Pt-Cl/° | 84.5 | 84, 92 |

| Cl-Pt-Cl/° | 95.5 | 93.4, 90.5 |

Comparing with literature values, Gaussian calculations are very accurate with actual measurements, except that the real complex seem to be slightly asymmetric (given there are two N-Pt-Cl and Cl-Pt-Cl angles), probably due to lone pair repulsions and slightly different atom/group sizes between Cl and NH3. Nevertheless values fall in very close range with literature data.

Pt-Cl' bonds are longer than Pt-N by approximately 0.35Å, conferring an inherent weakening in Pt-Cl' bonds, and thus a potential target for substitution.

It is noted that according to literature[13], the structural propoerties and spectroscopic properties of this anion is very much dependent on its countercation. Here, literature data is taken where the countercation is K+, a common cation for the complex.

Vibration Frequencies

Data for vibrational frequency of [PtCl3(NH3)]-: DOI:10042/to-5811

| Description | Vibration | Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Freq/cm-1[13] |

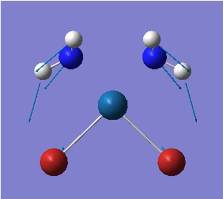

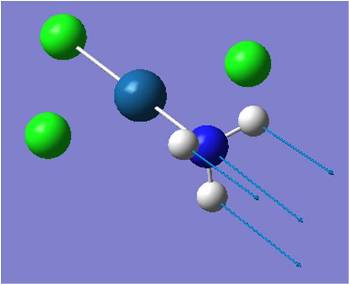

| Pt-Cl' symmetric stretch (two Cl's trans to each other) |  |

277 | 0 | N.A. |

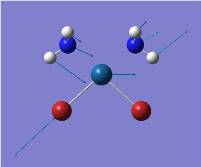

| Pt-Cl' asymmetric stretch (two Cl's trans to each other) |  |

298 | 77 | 315 |

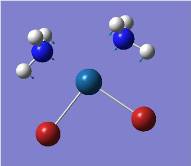

| Pt-Cl stretch (Cl trans to NH3) |  |

314 | 29 | 325 |

| Pt-N stretch |  |

492 | 14 | 489 |

As mentioned in Parts I and II of this module, vibrations which result in zero change in dipole moments are IR-inactive, i.e. leading to zero intensity and not observed on IR spectrum. Bearing that in mind, Pt-Cl symmetric stretch naturally will not have a matching literature value due to its dipoles cancel out in its motion; other IR peaks are in excellent agreement with experimental data.

Since vibration frequency is proportional to the energy required to vibrate the bond (E=hf), it is thus proportional to the energy and strength of a bond. Hence, the two P-Cl' bonds (at 277 and 298 cm-1), of lower frequencies, are weaker than Pt-N and Pt-Cl. Therefore, Pt-Cl' becomes a sensible breaking point for substitution.

NBO/Charge Distribution

Data for NBO Analysis of [PtCl3(NH3)]- : DOI:10042/to-5810

| Atom | Natural Charge |

| Pt | +0.137 |

| Cl' (Cl cis to NH3) | -0.476 |

| Cl (trans to NH3) | -0.444 |

| N | -1.022 |

| Bond | Energy/kJ mol-1 | Occupancy |

| Bonding Pt-Cl' (cis to NH3) | -708 | 1.91 |

| Bonding Pt-Cl (Cl trans to NH3) | -682 | 1.895 |

| Bonding P-N | -1021 | 1.923 |

A discrepancy is seen here as apparently Pt-N bond is the strongest of all judging from NBO analysis -- its localised natural charge difference between itself and Pt is the largest (difference of 1.159 as compared to 0.613 for Pt-Cl'), indicating the most polar bond of all; also, the energy of the bonding Pt-N is 0.118au or 313 kJ/mol more stable than Pt-Cl' bonding interaction. Furthermore, even the Pt-Cl bond seems to be less stable than Pt-Cl' by the same arguments. This contradicts the hypothesis that Pt-Cl' is weakened by trans effect and Cl' gets substituted.

A possible explanation for this deviation could be due to the Cl' ligands having better donor properties. Despite being more electronegative than N (Pauling's electronegativity for Cl = 3.16, for N = 3.04), Cl- being a better donor than NH3 could have donated electron density to the central Pt(II), strengthening the bond while reducing the charge on itself due to the shift of electron density. Also, strength of bond also depends on factors like atomic radius (Cl is larger than N). Besides, the repulsion between lone pairs on Cl' and non-bondng orbitals of Pt could have further weakend the bond.

However, this could also be an inherent limitation of computational method used, not being able to predict the outcome of this reaction whose trend and rationalisation was only proposed based on empirical observation and not an absolute rule.

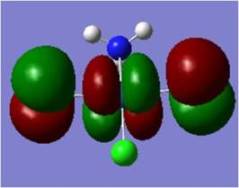

Molecular Orbitals

Data for MO of [PtCl3(NH3)]- :DOI:10042/to-5810

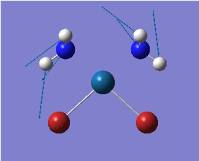

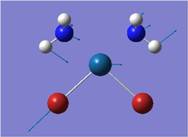

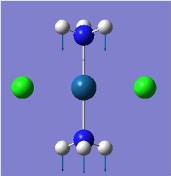

Comparing Cis- & Trans- Products: [PtCl2(NH3)2]

Cis- 2 and trans-isomeric 3 products are compared and their trans-effect, if any, is observed via computational prediction. It is expected that the Pt-N bonds in trans isomer 3 is stronger than in cisplatin 2, due to the absence of strong trans-directing Cl ligand being trans to NH3 in the trans isomer 3.

Bond Lengths & Angles

| Cis (Gaussian) | Cis(Lit)[14][15] | Trans (Gaussian) | Trans (Lit)>[15] | |

| Pt-Cl/Å | 2.41 | 2.385 | 2.43 | 2.32 |

| Pt-N/Å | 2.11 | 2.080 | 2.07 | 2.05 |

| N-Pt-N/° | 99.3 | 98.8 | 180.0 | 180.0 |

| Cl-Pt-Cl/° | 82.0 | 82.5 | 180.0 | 180.0 |

| Cl-Pt-N/° | 96.7 | 96.0 | 90.0 | 91.5, 88.5 |

Vibration Frequencies

Data for IR analysis of cis-[PtCl2(NH3)2] :DOI:10042/to-5824

Data for IR analysis of trans-[PtCl2(NH3)2] :DOI:10042/to-5823

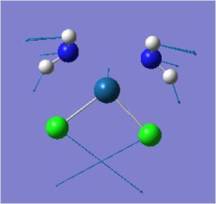

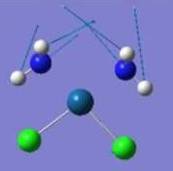

| Cis-[PtCl2(NH3)2] | Trans-[PtCl2(NH3)2] | |||||||

| Description | Vibration | Freq/cm-1 | Intensity | Lit Freq/cm-1[16] [17] | Vibration | Freq/cm-1 | Intensity | Lit Freq/cm-1[16][17] |

| Pt-Cl Scissoring |  |

136 | 0 | 148 |  |

119 | 10 | NA |

| Pt-N Rocking |  |

225 | 24 | 220 |  |

208 | 42 | NA |

| Pt-Cl asymmetric stretch |  |

321 | 0 | 317 |  |

301 | 0 | NA |

| Pt-Cl symmetric stretch |  |

330 | 77 | 325 |  |

330 | 52 | 327 |

| Pt-N asymmetric stretch |  |

463 | 29 | 489 |  |

510 | 6 | 505 |

| Pt-N symmetric stretch |  |

468 | 14 | 492 |  |

526 | 0 | NA |

Firstly, comparing Gaussian calculated values and literature values, their values are in good agreement indicating a reliable prediction by Gaussian. Vibrations which result in zero dipole change are again not physically observed in actual IR spectra, which is confirmed as shown in the table above.

Secondly, as expected, the IR frequencies of P-N stretches are indeed higher in trans-isomer 3 than in cis-isomer 2, confirming that P-N bonds in isomer 3 is stronger and needs more energy to vibrate. This is due to Cl ligands not being trans to NH3 in isomer 3, thus no competition for donation of electron density into central Pt, and so it allows NH3 to form stronger bond to Pt by donation.

NBO/Charge Distribution Analysis

Data for NBO analysis of cis-[PtCl2(NH3)2] :DOI:10042/to-5820

Data for NBO analysis of trans-[PtCl2(NH3)2] :DOI:10042/to-5822

| Atom | Natural Charge of cis-[PtCl2(NH3)2] | Natural charge of trans-[PtCl2(NH3)2] |

| Pt | +0.251 | +0.259 |

| Cl | -0.398 | -0.435 |

| N | -1.026 | -1.013 |

| cis-[PtCl2(NH3)2] | trans-[PtCl2(NH3)2] | |||

| Energy/kJ mol-1 | Occupancy | Energy/kJ mol-1 | Occupancy | |

| Bonding Pt-Cl | -1087 | 1.885 | -1103 | 1.900 |

| Bonding Pt-N | -1400 | 1.925 | -1414 | 1.912 |

Again, in terms of bond polarity (charge distribution), it seems counterintuitive that Pt-N is stronger than Pt-Cl in trans-isomer 3 (smaller charge difference between Pt and N in trans-isomer 3, 1.277 versus 1.272 ), unlike as expected where Pt-N bond is supposed to be strengthened. Again, it is possibly explained by bond strength being determined by factors other than polarity, eg atomic sizes and donor-properties that causes polarity representation to be somehow misleading. Moreover, looking at NBO population and energies, it agrees with expectation that Pt-N bonding orbital is lower in energy for trans-isomer 3 than its cis counterpart, by about 14kJ/mol. This suggests that the strength or energy of a bond consists of factors other than merely polarity indicated by the charges.

Generally, these results agree with trans-effect, where the absence of a strong trans-directing ligand removes the competition for donation into central Pt(II), thus allowing the weaker trans-directing ligand to form stronger dative bond with Pt(II). Hence, Pt-N in trans-3 is stronger than in cis-2.

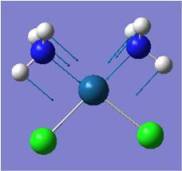

Substitution Effect on cis-Product: Replace NH3 With PEt3

Cisplatin 2 is studied alone, by substituting its ligands and looking at the trans-effect it has on the other unchanged ligands.

Firstly, the two ammonia ligands are replaced by triehtylphosphine PEt3, which is a much stronger σ-donating and nucleophilic ligand than ammonia. PEt3 is hence much higher up the trans-effect series than both Cl- and NH3. Now, there is a competition of donation into Pt between PEt3 and Cl ligands, as they are trans to each other. Chloride 'loses' out, as PEt3 donotes into Pt(II) and the total electron occupation in Pt d-orbital is now higher, preventing the trans Pt-Cl bond to form a strongly donating dative bond. It is now expected that Pt-Cl bonds in complex 4 is weakened as compared to 2.

Complex 4 should be expected to produce lower IR frequencies for Pt-Cl stretches, longer Pt-Cl bond length, a smaller difference in charge distribution between Pt and Cl and perhaps a less stable Pt-Cl bonding orbital.

- steric bulk!

Bond Lengths & Angles

| cis-PtCl2(NH3)2 | cis-PtCl2(PEt3)2 | Lit for PtCl2(PEt3)2 | |

| Pt-Cl/Å | 2.41 | 2.40 | 2.42 |

| Pt-N or Pt-P/Å | 2.11 | 2.34 | 2.25 |

| N-Pt-N or P-Pt-P/° | 99.3 | 100.5 | not found |

| N-Pt-Cl or P-Pt-Cl/° | 82.0 | 88.2, 89.2 | not found |

| Cl-Pt-Cl/° | 96.7 | 82.0 | not found |

Upon comparison with literature data, it is revealed that Gaussian calculation predicts a rather accurate structure as bond lengths correspond well with reported data, though angle measurements are not found. The more distorted angles deviating from the ideal square planar 90° is most likely due to the spatial constraints exerted by bulky PEt3 ligands. However, it is expected that Pt-Cl is longer and weaker in complex 4 than in 2, which is not exactly reflected by Gaussian's model where the Pt-Cl bond length is similar in both complexes. Hence, bond length, which is supposed to be a significant indicator of bond strength, seems not to mirror theoretical prediction. However, it is noted that the optimisation for complex 4 yields an extremely negative (i.e. stable) energy as compared to other complexes by nearly 1×106kJ/mol, at odds with other energies even though the same method and basis set was applied. This anomaly could have been due to:

- the significant steric bulk of PEt3 ligands as compared to smaller NH3, thus making it not a fair ground for comparison across these complexes; and

- the optimised energy is very relative value calculated by the programme.

The fact that this optimised energy for 4 may not be reliably compared with other complexes can also lead to bond lengths generated not being comparable. After all, even literature data for the same compound produced by different projects or experiments can church out different values -- for instance comparing structural data for cisplatin 2 done by Michalska et al[14] and Barker et al[15]. Meanwhile, other parameters like IR and NBO are explored to further verify the relative bond strengths of Pt-Cl.

IR Frequencies

Data for IR analysis of cis-PtCl2(PEt3)2 :DOI:10042/to-5819

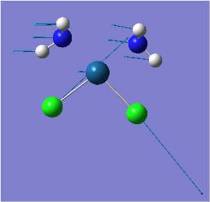

| cis-PtCl2(PEt3)2 | cis-PtCl2(NH3)2 | ||||

| Description | Vibration | Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity | Lit Freq/cm-1[17] | Frequency/cm-1 |

| Pt-Cl asymmetric stretch |  |

293 | 33 | 281 | 321 |

| Pt-Cl symmetric stretch |  |

308 | 30 | 308 | 330 |

| Pt-P asymmetric stretch (both Pt-P concerted) |  |

498 | 38 | not found | 463 |

| Pt-P symmetric stretch (both Pt-P concerted) |  |

513 | 12 | not found | 468 |

| Pt-P stretch (Only one Pt-P) |  |

55, 560 | 0, 0 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Pt-P Rocking |  |

654 | 6 | not found | 225 |

| Pt-P Scissoring |  |

656 | 7 | not found | N.A. |

Again, Gaussian calculated IR frequencies correspond very well with literature values, unless the intensity if predicted to be zero due to cancellation of dipole moment during vibration motion. As opposed to bond lengths, the stretching frequencies of Pt-Cl, both asymmetric and symmetric stretches, do agree with theoretical prediction that these Pt-Cl frequencies are lower in complex 4 than in 2, indicating a weaker Pt-Cl bond in 4.

Charge Distribution/NBO Analysis

Data for NBO Analysis of cis-PtCl2(PEt3)2 :DOI:10042/to-5817

| Atom | Natural Charge of cis-PtCl2(PEt3)2 | Natural Charge of cis-PtCl2(NH3)2 |

| Pt | -0.249 | +0.251 |

| Cl | -0.417 | |

| -0.402 | ||

| Cl (ave) | -0.410 | -0.398 |

| P or N | +1.018 | |

| +1.035 | ||

| P (ave) | +1.027 | -1.026 |

| cis-PtCl2(PEt3)2 | cis-PtCl2(NH3)2 | |||

| Energy/ kJ mol-1 | Occupancy | Energy/ kJ mol-1 | Occupancy | |

| Pt-Cl | -1040 | +1.889 | -1087 | +1.885 |

| Pt-P or Pt-N | -1029 | +1.827 | -1400 | +1.925 |

PEt3 being a much stronger electron donor, donates much electron density into Pt(II), resulting in a overall negative charge on Pt and a positive charge on P, in great contrast to the charges present in complex 2 with NH3. It is observed here that the difference in charges between Pt and Cl is only 0.16 on complex 4 but is 0.65 on complex 2, indicating a much less polar Pt-Cl bond in complex 4, in turn implying a weaker Pt-Cl bond (in terms of polarity) in complex 4.

NBO-wise, Pt-Cl bonding orbital is about 40kJ/mol lower in energy for complex 4 than for 2, provided if they actually do provide a good basis for comparison given the tremendous disparity in their optimised energy at the beginning.

Substitution Effect on cis-Product: Replace Cl With Br

Now, looking at cisplatin 2, its chloride ligands are now replaced with bromide ones, which are more nucleophilic and higher up in the trans-directing series, and thus is expected to exert a stronger trans effect on the ligands trans to themselves, i.e. Pt-N bonds. Bromide, being less electronegative than chloride, would reduce the electron density between Pt-Br as compared to Pt-Cl, weakening this bond, coupled with its larger radius, would lengthen this Pt-X bond. However, being more electron-rich, it acts as a better nucleophile and exerts a stronger trans effect and weakens the Pt-N bond to a larger extent than in complex 2.

By analysis, it is expected that in complex 5, a weaker Pt-Br IR stretch and longer Pt-Br bond length should be seen, together with raised energy for Pt-Br bonding interaction. Also, a weaker Pt-N IR stretch, longer Pt-N and raised Pt-N bonding orbital energy should be observed due to stronger trans-effect present.

Bond Lengths & Angles

| cis-PtCl2(NH3)2 | cis-PtBr2(NH3)2 | |

| Pt-X/Å | 2.41 | 2.54 |

| Pt-N/Å | 2.11 | 2.13 |

| N-Pt-N/° | 99.3 | 95.2 |

| N-Pt-X/° | 82 | 83.9 |

| X-Pt-X/° | 96.7 | 97.1 |

From the table above, it can be seen that Pt-Br and Pt-N bonds in complex 4 are indeed longer and weaker than their counterparts in complex 2, indicating the predictions mentioned above are verified in terms of bond lengths.

IR Frequencies

Data for IR analysis of cis-PtBr2(NH3)2 :DOI:10042/to-5814

The IR peaks obtained match very well with corresponding literature values, indicating a reasonably reliable calculation done by Gaussian. Looking at the Pt-Br asymmetric and symmetric stretches and scissoring, they are all of lower frequency than corresponding Pt-Cl vibration modes, indicating a weakening of Pt-Br bond. Looking at Pt-N bonds, it is also noted that its asymmetric and symmetric stretches and rocking are of lower frequencies than corresponding vibrations in complex 2, again indicating the presence of trans effect has weakened the Pt-N bonds.

Charge Distribution/NBO Analysis

Data for IR analysis of cis-PtBr2(NH3)2 :DOI:10042/to-5812

| Atom | Natural Charge | |

| cis-PtBr2(NH3)2 | cis-PtCl2(NH3)2 | |

| Pt | +0.116 | +0.251 |

| X | -0.326 | -0.398 |

| N | -1.029 | -1.026 |

| cis-PtBr2(NH3)2 | cis-PtCl2(NH3)2 | |||

| Energy/kJ mol-1 | Occupancy | Energy/kJ mol-1 | Occupancy | |

| Bonding Pt-X | -1008 | 1.868 | -1087 | 1.885 |

| Bonding Pt-N | -1395 | 1.928 | -1400 | 1.925 |

The natural charge difference between Pt and Br is 0.442 while between Pt and Cl in complex 2 is 0.649. The smaller difference in Pt-Br indicates a less polar bond and thus reducing its bond strength in complex 4. Similarly, the charge difference between Pt-N in complex 4 is 1.145 while that in 2 is 1.277. Again, the smaller polarity in Pt-N bond in 4 confers a weakened bond.

Looking at the bonding orbital energies, it is seen that Pt-Br bonding interaction is raised in energy by 80kJ/mol compared to Pt-Cl, indicating a destabilised and thus weaker Pt-Cl bond. Similarly, Pt-N bonding orbital of complex 4 is raised in energy by about 5kJ/mol than that in 2, again showing a weakened Pt-N bond.

In conclusion, these various paramters like bond lengths, IR peaks, charge distribution and NBO analysis, it shows that the Pt-Br and Pt-N bonds are indeed weakened, by trans-effect, in complex 4 than in corresponding bonds in 2, hence successfully confirming and predicting trans-effect trend.

Conclusions

In conclusion for this module, it can be seen that with computational methods alone (at least with methods performed here), it can be tricky and risky to predict certain outcomes and properties for trans effect on square planar Pt(II) complexes. However, it is a very useful tool to aid our understanding in rationalising possible explanations, by looking at parameters like structural properties, IR frequencies, population anaylysis, or NBO analysis. When results do not agree with initial rationalisation, other parameters and factors need to be considered before a conclusive result can be obtained. Other times, it could be the inherent limitation of computational methods to not be able to mimic an unrationalised or rationalisation based on merely hypothesis/proposed explanation as a complicated combination of different factors can come into play for more complex compounds. It has great potential to do much complicated calculations and modelling not conveniently done manually.

References

- ↑ M. R. Hartman, J. J. Rush, T. J. Udovic, R. C. Bowman Jr and S. J. Hwang J. Solid State. Chem., 2007, 180, 1298 - 1305 DOI:10.1016/j.jssc.2007.01.031

- ↑ M.S. Schuurman, W.D. Allen, H.F. Schaefer III, J. Comput. Chem., 2005, 26, 1106: DOI:10.1002/jcc.20238

- ↑ J. Glaser, Acta Chem. Scand. A, 1979, 33, 789

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, Inorg. Chem., 1979, 18, 14 - 17 DOI:10.1021/ic50191a003

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg and R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680 - 2682 DOI:10.1021/ic50187a062

- ↑ G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica Chemica Acta 254 (1997) 167 - 171.

- ↑ G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica Chemica Acta 254 (1997) 167 - 171.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 F. A. Cotton, Inorg. Chem., 1963, 3, 702 - 711 DOI:10.1021/ic50015a024

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Z.Chval, M. Sip, J.V. Burda, J. Comput. Chem., 2008, 29, 2370-2380

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 J. Chatt, L.A. Duncanson, L.M. Venanzi, J. Chem. Soc., 1955, 4456-4460 DOI:10.1039/JR9550004456 10.1039/JR9550004456

- ↑ L.E. Orgel, J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem., 1956, 2, 137

- ↑ Y.P. Jeannin, D.R.Russell,Inorg. Chem., 1970, 9, 778DOI:10.1016/j.jssc.2007.01.031

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 A. Oksanen, M. Leskela,Acta. Chem. Scand., 1994, 48, 485-489DOI:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.48-0485

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 D. Michalska, R. Wysokinski,Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun., 2004, 69, 63-73DOI:10.1135/cccc20040063

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 M. Barber, J.D. Clark, A. Hinchliffe, J. Mol. Struct., 1979, 57, 169-173DOI:10.1016/0022-2860(79)80242-2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "cis trans bond length" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 16.0 16.1 E.B. Burgina, E.N. Yurchenko, J. Struct. Chem., 1988, 29, 378-387DOI:10.1007/BF00743993

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 J. Hiraishi, I. Nakagawa, T. Shimanouchi, Spectrochim. Acta. A, 1968, 24, 819-832DOI:10.1016/0584-8539(68)80180-1