Rep:Mod:jcl08M1

Chemistry Computational Lab

Module 1: Structure and spectroscopy (Molecular mechanics/Molecular orbital theory)

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

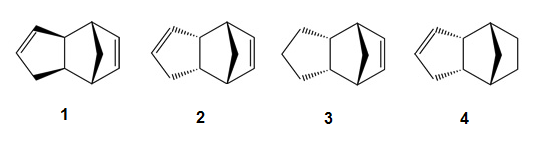

Cyclopentadiene dimerises to form dimer via a mechanism of [π4+π2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction. This theoretically can result in either molecule 1 (Exo dimer) or 2 (Endo dimer).

Repeat simulations was carried out using ChemBio3D. The lowest total energy obtained for Exo isomer was 31.8796 kcal/mol, whilst for Endo isomer the energy was 34.0053 kcal/mol. This indicates that Endo dimer has less strained conformation(mainly due to less torsion in the structure), hence thermodynamically more stable. . This matches with experimental result[1] on the thermal decomposition stability of the two dicyclopentadienes.

Table 1. Comparsion of the individual contribution towards the total energy for molecule 1 and 2

Most factors contribute to the total energy are similar in both isomers, but there is a 1.95 kcal/mol difference in torsion.

|

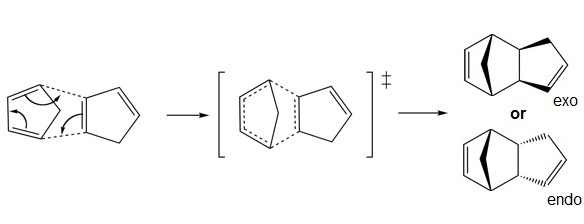

However, in real synthesis the endo product predominates as the reaction follows the Alder's endo addition rule. The transition state of the endo addition is lower in energy. A lower activation energy is required for the reaction hence a higher rate of reaction, giving endo dimer as the kinetically more favourable product. This can be explained by considering the second orbital interaction as shown below, where favourable overlap occur between non bonded carbon, hence lowering the energy level of the transition state.

From above, we can conclude that the cyclodimerisation of cyclopentadiene is kinetically controlled rather than thermodynamically.

Table 2 shows a comparison of the total energy and individual contributing factors between derivatives 3 and 4. Derivative 4 is a less hindered structure with a total energy of 31.1811 kcal/mol, whereas derivative 3 has a total energy of 35.9833 kcal/mol. Hence derivative 4 is thermodynamically more stable. The main difference in energy between the derivatives was the bend energy, where derivate 4 was 4.396 kcal/mol more stable. A greater amount of bend strain was released during hydrogenation for the double bond in derivative 4 (adjacent to the strained bridge head) than the double bond in derivative 3. This relative scale of strain at the sp2 carbon can be identified by looking at the angles at the double bond. They are 107.5850° and 107.5616° for derivative 3, much further away from the ideal 120° than 112.3682° and 113.0735° of derivative 4.

Therefore, we can conclude that derivative 4 is relatively more likely to be the product of the hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene dimer from the thermodynamic prospective.

Table 2. Comparsion of the individual contribution towards the total energy for derivative 3 and 4

|

| molecule 1 | molecule 2 | molecule 3 | molecule 4 | ||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

The MM2 minimisation has a pitfall, in which the optimisation might reaches a local energy minimum instead of a global minimum. Hence the geometry of the optimisation might not be the lowest energy conformation, thus multiple start conformations were optimised in order to obtain a more reliable result.

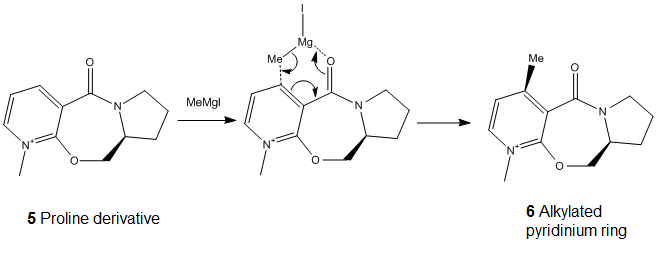

In this part, we are looking at the nucleophilic addition of methyl magnesium iodide to N-methyl pyridoxazepinone (molecule 5). This reaction has a high regio- and stereo- selectivity due to coordination between the electropositive Mg of the Grignard reagent and the electronegative oxygen from the carbonyl group. The C=O bond lies 11.1398° above the ring, the coordination between the Magnesium and the oxygen results in the formation of a 6 electron pericyclic transition state. Thus MeMgI attacks from the top, the addition of methyl group to the proline derivative would also take place above the ring due to the coordination, leading to the observed absolute stereochemistry of the reaction.[2]

Table 3. Different starting conformation for minimization of molecule 5

|

From the three different starting conformations, we can see the total energy vary enormously. The lowest energy obtained was conformation 1 with an energy of 43.1284 kcal/mol. The main contributing factors are bend energy and 1,4 Van der Waals, indicating that that there are large deviations from the ideal bond lengths and intermolecular forces within the molecule.

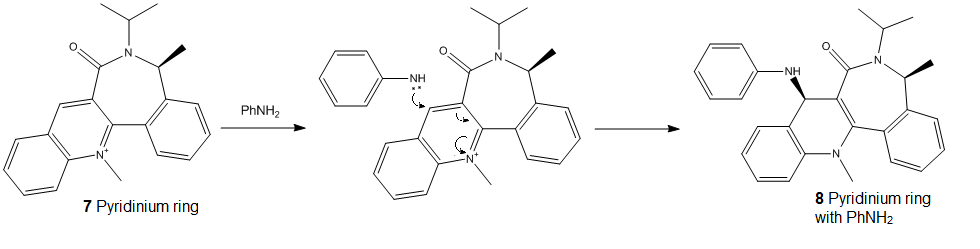

Similar reason applies to the nucleophilic addition of aniline to N-methyl quinolinium salt 7, resulting in highly regio- and stereo- selectivity.

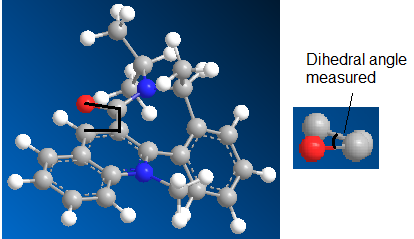

The lone pair repulsions between the aniline nitrogen and the carbonyl group oxygen give rise to stereoelectronic control. The position of the carbonyl group influences which side the aniline attacks the molecule. Steric hindrance between the large phenyl group and the carbonyl group also contribute to the regio-/stereo- selectivity. If we look at the dihedral angle of carbonyl group against the plane of the ring, we would know that the C=O is pointing away from the screen with an angle of -19.4479° (ie. 19.4479° below the ring). Therefore, the aniline group would react from the top, giving the stereo-specificity of product 8.

Table 4. Different starting conformation for minimization of molecule 7

|

The lowest energy obtained was conformation 2 with an energy of 63.4008 kcal/mol. The main contributing factor is the 1,4 Van der Waals, indicating that that there are large deviations from the optimal intermolecular forces within the molecule.

Note: If the methyl magnesium iodide(MeMgI) was included into the MM2 minimization, it gives an error "No atom type was assigned to the selected atom!" as there are no experimental values of the atom in the model.

| molecule 5 | molecule 6 | molecule 7 | molecule 8 | ||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

To improve the reliability and accuracy of the result, a different computational calculation is required. MOPAC method can be used instead of molecule mechanics (MM2 force field), as it introduces molecular orbitals and electronic structure into the calculation to give more accurate energy and optimisation. Guaussian density functional theory is also an alternative mehtod, it has the advantage over the other two methods as it can minimise the energy of two different at the same time in respect of each other. Hence the optimised conformation of the molecule would be more accurate when compare to the conformation of the molecules in the real reaction.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

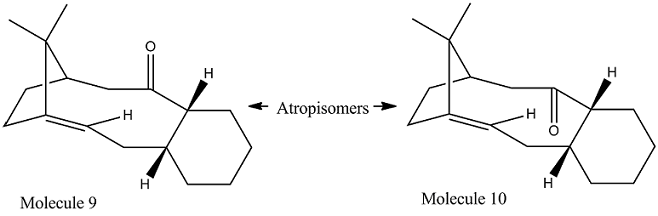

Atropisomerism arises when there are steric strain hinders rotation about single bonds and prevents interconversion of isomers. The key intermeidate 9/10 in the total synthesis of Toxal[3] would be one of the examples[4]. The structure of these 2 atropisomers were proposed by Paquette, with the carbonyl group pointing either up or down.

Table 5. Comparison between different optimized conformation of both molecule 9 and 10

|

It is clear that molecule 9 thermodynamically prefer a twisted boat conformation over chair conformation. The total energy from the MM2 simulation for chair conformation of 9 is 119.6860 kcal/mol,which is more than half of the total energy of its twisted boat conformation 48.9228 kcal/mol. The main difference in contribution between the two conformation were from the bend strain of the structure and the 1,4 Van der Waals interaction within the molecule. The same applies to molecule 10, but with the chair conformation being more stable. The total energy of chair conformation of 10 is 44.2925 kcal/mol, and it is 123.5935 kcal/mol for its twisted boat conformation. In comparison between the two atropisomers, molecule 10 with the carbonyl group pointing downwards has a lower energy of 44.2925 kcal/mol than 48.9228 kcal/mol of molecule 9. This is reconfirmed by using MMFF94 minimisation, in which molecule 10 is thermodynamically more stable by around 10 kcal/mol. Therefore, from the thermodynamic prospective, on standing molecule 9 would atropisomerise to molecule 10.

Molecule 9 and 10 are examples of hyperstable alkene, also known as hyperstable olefins. These are alkene generally contained in a trans-cycloalkene unit with at least 8 carbon atoms in a bridgehead style. Due to their bridgehead positions, they are comparatively less strained than the parent hydrocarbon and have a negative olefin strain value. Their cage structure provides extra stability, hence they are very unreactive and is not prone to hydrogenation. Such alkenes are suggested to be thermodynamically more stable than any of their positional isomers.[5]

| Optimized molecule 9 in chair conformation | Optimized molecule 9 in twisted boat conformation | optimized molecule 10 in chair conformation | Optimized molecule 10 in twisted boat conformation | ||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Theory Modelling

Part 1

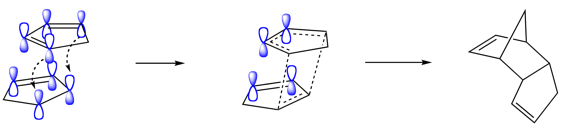

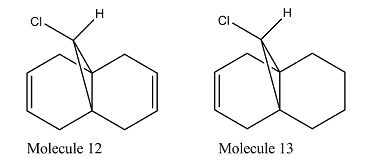

In this section we are looking at the regio-selective of dichlorocarbene. As the endo stereoselectivity in Diels Alder cycloadditions was attributed to "secondary orbital" interactions, an alternative method other than Molecular Mechanics is required in order to interpret the molecule. MOPAC/PM6 method was used to optimized the geometry of the structure, it was also used to approximate the valence-electron molecular wavefunction, in which the orbitals are shown graphically as a result.

Firstly, MM2 method was carried out to cleans the geometry up prior to applying an electronic method. Then the MOPAC/PM6 method was applied, giving the orbitals below.

To identify the sterochemistry of the reaction, we mainly need to examine the HOMO orbitals of the molecule, as the HOMO (Highest occupied molecular orbital) involves in the breaking of the double bond and the LUMO (Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital) involves in accepting electrons and making new bond. In terms of available orbital to accept electrons, the LUMO of the molecule shows that attack is possible for both exo and endo alkene. However, from the graphical representation of HOMO and HOMO-1, we would notice that the orbital has a higher electron density on the endo side of the molecule. Hence the electrophilic addition would occur on the nucleophilic endo alkene than the less electron rich exo alkene, giving the steroselectivity of the Diels Alder cycloaddition. This electron density is due to the antiperiplanar overlap between the Cl-C σ* orbital and the exo-π orbital, where the HOMO-1 is stablised relative to the HOMO[6]. Therefore, from the frontier orbital and an electrostatic perspective,the endo double bond is more nucleophilic and prone to electrophilic addition.

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

Part 2

In part two, we used the Guassian interface density functional approach B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) to calculate the expecting Infrared spectrum of molecule 12 and its monoalkene derivative(molecule 13).

|

|

|

|

Due to the interaction between the C-Cl σ* orbital and the exo-π orbital, the exo C=C is weaken. Thus its bond length is expected to be longer than endo C=C bond. This is clearly reflected not only on the simulated bond length, where exo C=C is 1.33552Å long and endo C=C 1.33189Å, but also by a lower wavelength on the IR spectrum for exo C=C. The IR spectrum of molecule 12 has two peaks at around 1737.02cm-1 (exo C=C)and 1757.44cm-1 (endo C=C), both representing C=C bond stretch. The 1737cm-1 peak disappeared for the IR spectrum of molecule 13 , matches with the hydrogenation of the exo C=C bond. In both spectrum, we can observe a strong peak at around 770cm-1, which represents the C-Cl stretch. As the interaction between the C-Cl σ* orbital and the exo-π orbital is lost in molecule 13, the C-Cl is expected to be strengthen. This is confirmed by the 4 cm-1 increase in frequency for C-Cl from molecule 12 to molecule 13.

Table 9. Calculated IR spectrum of molecule 12 using DFT/RB3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

|

|

Structure based Mini project using DFT-based Molecular orbital methods

Synthesis of diasteroisomers of 4-acetyl-2,6-diaroyl-3,5-diaryl-4-ethoxycarbonylthiane-1,1-dioxides

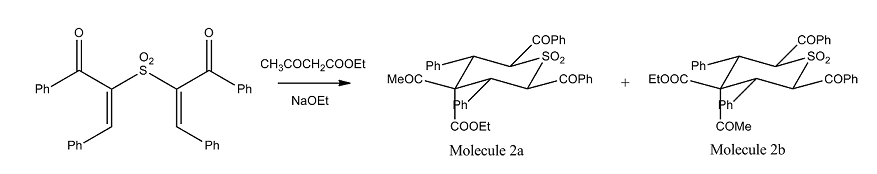

Reaction Scheme

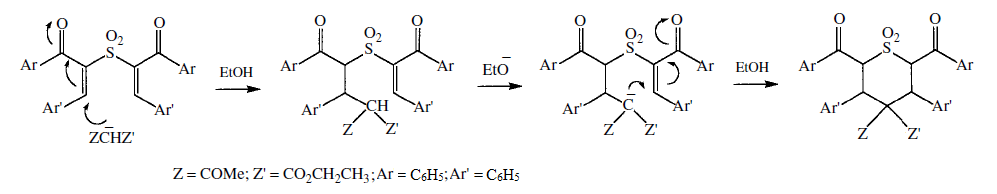

Proposed mechanism

Labeling of the carbon

The Carbon in the ring structure are labelled as above, starting with 1 being the sulphur and around the ring.

Energy optimisation

Conjugate addition of ethyl acetoacetate to 2,2-sulfonylbis(1,3-diarylprop-2-en-1-ones) results in a two diastereoisomer of 4-acetyl-2,6-diaroyl-3,5-diaryl-4-ethoxycarbonylthiane-1,1-dioxides differing in configuration at C-4. From the literature[7], molecule 2a is found to be the major product of this reaction (~65%) while 2b being the minor product (35%). One might therefore predict that 2a is the more stable isomer.

An optimization using DFT-mpw1pw91/6-31g(d,p) method was applied to both moelcule 2a and 2b, the total energy obtained for 2a(-2315.389 a.u.) is small than 2b(-2314.662 a.u.) Thus it is proven that 2a is a more stable structure as predicted.

The optimised structures are represented in Jmol.

Molecule 2a optimized using DFT=mpw1pw9/6-31G(d,p)

Molecule 2b optimized using DFT=mpw1pw9/6-31G(d,p)

Carbon-13 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Simulation

The optimised structures are then used to simulate the C13 NMR using the same method. The result are shown as below.

|

|

Table 8. Comparison between the simulated and experimental C13 NMR

|

The simulation result are similar to the experimental data, but error from the simulation can lead to 2-4 ppm difference from the original data for some peaks. However, the main characteristic between the molecule 2a and 2b are successfully produced in the simulation, which matches with the trend in the experimental result. For example, the experimental peak for CO(Me)has a shift of 205.2ppm(molecule 2a) and 213.8ppm(molecule 2b), where the peaks of the two molecule has a difference of 8.6ppm. The simulated result peaks has a shift of 201.4ppm(molecule 2a) and 209.5ppm(molecule 2b) with a difference of 8.1ppm, confirm with the experimental result to a good extend. This is also the case in CO2(CH2Me) and (CO)Me.

Graphical representation is used to show the similarity between the simulated result and the experimental data.

Infrared Spectrum simulation

Infrared spectrometry simulation was not considered as the spectrum for both structure would be the same as they are stereoisomers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the computational simulated result correspond well to the experimental result, and the energies of the molecule support the major/minor product suggestion from the literature. Thus the literature should have synthesised the correct product from their experiment. However, within the literature, it has not fully explain the reason behind its suggested mechanism, thus the simulation cannot provide any evidence in supporting the proposed mechanism.

Reference

- ↑ W.C. Herndon, C.R. Grayson, J.M. Manion, J. Am. Chem. Soc.., 2002, 124, 1130 DOI:10.1021/jo01278a003

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838. DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ K.C. Nicolaou, P.G. Nantermet, H. Ueno, R.K. Guy, E.A. Couladouros, E.J. Sorensen, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117, 624: DOI:10.1021/ja00107a006

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P.v.R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891: DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ Renuga, S., Selvaraj, S., Perumal, S., Lycka, A. and Gnanadeebam, M. (2001), DOI:10.1002/mrc.897