Rep:Mod:jamesmac

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

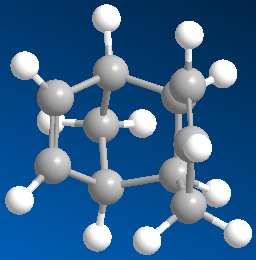

In theory, when cyclopentadiene dimerises it may form either the exo dimer (Product 1) or the endo dimer (Product 2). According to the MM2 force field calculations the total energy of the exo dimer is 31.88 kcal/mol and the energy of the endo dimer is 34.01 kcal/mol. Given that it is the endo dimer which predominates one can make the conclusion that the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is under kinetic control because the endo dimer is less energetically stable compared to the exo dimer. Because these reactions are irreversible under the reaction conditions the product formed the fastest will predominate, in this case, the endo dimer by virtue of its lower energy transition state.

Either the double bond found in the 6-membered ring may be hydrogenated or the one found in the 5-membered ring. The product formed by the hydrogenation of the 5-membered ring (Product 3) has a total energy of 36.87 kcal/mol whereas the energy of the product where the 6-membered ring is hydrogenated (Product 4) has a total energy of 29.25 kcal/mol. Product 4 in fact predominates in this reaction allowing one to conclude that this reaction is under thermodynamic control. Because these reactions are reversible at the given conditions they can equilibrate, in turn favouring the product most energetically stable.

Below the individual energy terms for both product 3 and product 4 have been tabulated.

| Product | Dipole/Dipole | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.163 | 1.24 | 18.7 | -0.753 | 12.8 | -1.34 | 6.04 |

| 4 | 0.141 | 1.14 | 13.0 | -0.564 | 12.4 | -1.34 | 4.43 |

As the table above shows, the energy contributions arising from dipole/dipole interactions, stretches, stretch-bends and non-1,4 Van Der Waal are all relatively small (no more than 2 kcal mol-1 in magnitude). This leaves one to conclude that the relative stabilities of these two molecules is governed predominantly by bond bending and to a lesser extent, 1,4 Van Der Waal interactions. Equally it is these two terms which give rise to the energy difference between the two products with bond bending in product 3 raising its energy by an extra 6 kcal mol-1 relative to product 4 and 1,4 Van Der Waals another 1.5kcal mol-1.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring

Reaction 1

The first reaction we will be looking at is the alkylation of prolinol with a Grignard reagent (MeMgI in this case). The Grignard reagent will attack the aromatic ring at the carbon para- to the positively charged Nitrogen atom resulting in an addition of a methyl group to the molecule. The reaction scheme is illustrated below.

As the above reaction scheme illustrates the Grignard reagent can in theory attack the ring from either above or below the ring resulting in 2 possible products. To understand the stereochemistry of the product, the stereochemistry of Prolinol must first be understood. First of all Prolinol's structure as seen above was drawn and minimised using the MM2 force field, this yielded a total energy of 43.14 kcalmol-1 and the following potential energy terms.

| Reactant | Charge/Dipole | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | -3.99 | 2.05 | 14.2 | 0.135 | 5.18 | -0.583 | 16.5 |

As a sidenote, it was noticed that when trying to run the MM2 force field calculations with the MeMgI drawn as well as Prolinol the calculation would not run stating that the "atom type could not be specified". As such the MeMgI component has to be removed in order to proceed with the minimisation.

It should be noted that the above results are inaccurate due to a bug pertaining to the MM2 force field calculations. To account for this MOPAC orbital calculations were also performed on the molecule (repeated for the next reaction as well)to work out the energies of formation of said molecules. For Prolinol the heat of formation was worked out to be 93.91 kcal/mol. It was noticed that operating the MM2 force field calculation optimised Prolinol's structure in such a way that the rings displayed very little bending and the carbonyl group was near planar with the aromatic ring. The PM6 model however, illustrated a greater extent of bending in the 7-membered ring particularly and showed the carbonyl group to be bent out of the plane with respect to the aromatic ring by approximately 20-25o.

To confirm the stereochemistry of Prolinol, the conformations of the 5- and 7-membered rings will be used as starting points for energy minimisation. The resultant heats of formation will be compared to conclude the stereochemistry assumed by Prolinol.

As the picture to the right shows, the 7-membered ring is planar with respect to the aromatic ring (on the leftmost side) with the 5-membered ring somewhat raised (yet still parallel to the aromatic ring) by virtue of bond bending. It was found that changing the directionality of the bonds in the 7-membered ring (introducing bends and kinks into the ring) increased the energy of the system by a few kcal/mol. It is thought that the stereochemistry of the 7-membered ring is such that the carbonyl group may attractively interact with the nearby Hydrogen atom on the aromatic ring thus lowering the energy of the molecule. Equally increasing the angle the 5-membered ring makes with the plane of the aromatic ring was shown to increase the heat of formation to 124 kcal/mol (likely a result of torsional strain). It seems that the 5-membered ring is angled so as to reduce non-bonding repulsive interactions made with the atoms on the 7-membered ring whilst keeping the torsional strain as low as possible. Bearing this in mind it can be concluded that the optimal structure agrees with the reactant drawn in the scheme above, however it is of note that the carbonyl is slightly bent out of the plane of the aromatic ring (imagined as pointing "up" out of the computer screen).

Both the MM2 and MOPAC optimisation models work by considering all of the forces and interactions within a molecule and then optimising them so as to achieve the lowest possible total energy for the molecule. Such models are therefore relatively simple in that they don't account for all of the factors which contribute to a molecule's total energy. Aromaticity and resonance stabilisation are an example of this. In this molecule it can be expected that the 6-membered aromatic ring and the nearby carbonyl group will display electron delocalisation giving rise to multiple resonance forms. Analysis of the molecular orbital surfaces supports this, showing delocalisation and extension of the pi-electron cloud from the 6-membered ring into the 7-membered ring by virtue of the electron-withdrawing Oxygen atoms. Naturally, such an effect will work to stabilise the overall energy of the molecule. Unfortunately the MM2 and MOPAC models don't account for conjugation, aromaticity and secondary orbital overlap effects and therefore it can be concluded that the model will be somewhat inaccurate, especially for molecules featuring a large extent of conjugation and electron delocalisation.

This model is also rather simple in that it optimises an isolated molecule, considering only intramolecular interactions. It also important to account for intermolecular interactions, particularly molecules which can form a large number of attractive Van Der Waal interactions (Hydrogen bonds included) because such interactions may also dictate the adopted geometry of a molecule and thus its total energy. To obtain a true representation of these interactions a large number of molecules would have to be included in the model which would undoubtedly make the calculations far too complicated and much slower.

These force field optimisations themselves are rather simplistic in nature. When a molecule's geometry is optimised, it is optimised to the nearest stable conformation. This doesn't necessarily mean however, the most stable conformation possible. As seen above this effectively means that manual editing of a molecule is sometimes necessary to ensure the most stable conformation is arrived at.

It is thought that when the MeMgI moves in to attack the 4 position on the pyridine-derived ring the positively polarised magnesium centre can coordinate with the nearby carbonyl group thus stabilising the soon to be positively-charged magnesium atom and facilitating the C-Mg bond cleavage (see the above reaction scheme). Because the carbonyl group is somewhat bent out of the plane of the pyridine ring (as described above) it can be concluded that the Grignard reagent will attack the molecule such that the newly formed carbon-carbon bond will also lie out of the plane of the aromatic ring. This results in the product illustrated in the scheme.

Reaction 2

This reaction consists of a molecule of aniline adding onto a larger pyridinium ring system. The aniline molecule will add onto the aromatic ring para- to the positively charged Nitrogen atom (see previous reaction). The reaction scheme is illustrated below.

MM2 optimisation calculated a total energy of 63.5 kcal mol-1 with following potential energy terms.

| Reactant | Charge/Dipole | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | -4.88 | 3.95 | 11.7 | 0.403 | 9.82 | 4.15 | 29.3 |

Running the PM6 method gave a heat of formation of 156.2 kcal mol-1. As was seen for the previous reaction, the PM6 method yields an optimised molecule which shows more severe bending (relative to the MM2 optimised structure) in the 7-membered ring resulting in the carbonyl group making a greater angle with the plane of the aromatic ring. The conformation adopted by the molecule is illustrated below. The higher energy of molecule 7 compared to 5 can be attributed to higher torsional strain and greater Van Der Waal repulsive terms.

It can be seen that the 7-membered ring to which the carbonyl group is attached is much more bent than seen for reactant 5 and as such the carbonyl group is further bent out of the plane of the aromatic system. The more significant bent nature of the non-aromatic ring is caused by the kinks where the Nitrogen atom is and the neighbouring -CHMe group. In this case the 2 fused aromatic rings lie in the same plane as the 7-membered non-aromatic ring with a dihedral angle, again close to 0. The other aromatic ring, however makes an angle of approximately 45 to the non-aromatic ring.

The carbonyl group acts in a similar way here as it did in the previous reaction by stabilising and facilitating the removal of a cationic leaving group. Using one of its lone pairs to attack the aromatic ring, the aniline Nitrogen gains a positive charge during this reaction. To "quench" this charge a proton must be lost from said Nitrogen centre. By aligning with the carbonyl group (as seen before) a Hydrogen-bond-like interaction may form between the carbonyl oxygen and the proton to be removed. This stabilises and thus facilitates the removal of said proton. As such it is unsurprising that aniline will attack at a trajectory which is similar to the angle the carbonyl group makes with the aromatic ring allowing for this stabilisation to occur. This is why the aniline group is directed out of the plane of the aromatic ring as seen. Modelling also shows that in attacking this way the remaining Hydrogen (on the aniline Nitrogen) may align with the carbonyl group in the final product to form a stabilising Hydrogen-bond, lowering the product's total energy.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

As before, both isomer 9 and 10 need to be optimised using the MM2 force field. The total energies of isomer 9 and 10 are 44.3 kcal mol-1 and 54.4 kcal mol-1 respectively with the following energy terms and conformations.

| Isomer | Dipole/Dipole | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | -0.181 | 2.52 | 10.7 | 0.322 | 19.6 | -1.22 | 12.6 |

| 10 | 0.140 | 2.81 | 16.5 | 0.461 | 21.3 | -0.874 | 14.1 |

Bearing these results in mind it can be concluded that isomer 9 is the more stable of the two due to smaller bending and torsional energy terms. This is reflected in the fact that isomer 9 is much more open with the 5-membered ring bent to a lesser extent. Isomer 10 on the other hand shows the 5-membered ring to be bent at a much greater angle thus "closing" off the larger ring and increasing its energy. The fact that isomer 9 also has a slightly smaller 1,4-Van Der Waal term illustrates that by directing the carbonyl group out of the ring repulsive interactions with nearby atoms inside the ring are reduced giving a lower overall energy. It is the repulsive interactions between these atoms that forms the basis of the hyperstability of these alkenes with respect to their corresponding saturated forms. Before getting to this however the MM2 force field calculations will be performed on said alkanes. By directing the carbonyl group out of the ring the dihedral angle made with the neighbouring Hydrogen atoms can be increased, reducing steric clashing and bond electron-pair repulsions. This explains why the torsional strain energy is 3 kcal mol-1 smaller for isomer 9.

Isomers 9 and 10 were then optimised using the MMFF94 force field which yielded respective final energies of 60.6 kcal mol-1 and 76.3 kcal mol-1 . This agrees with the conclusion made above suggesting that isomer 9 is thermodynamically more stable due to the reduced strain associated with directing the carbonyl group out of the ring. These values however, may not be directly compared with the MM2-based results as the MMFF94 force field consists of a different set of parameters to those of the MM2 force field.

When a molecule is optimised using the MM2 force field method the adopted conformation will be the most stable conformation which is closest to the geometry of the drawn molecule. As such it is possible to further minimise a molecule' total energy by manually adjusting the atom positions before performing another optimisation calculation. This was done for the two isomers illustrated above.

It was thought that enlarging the central ring by adjusting the corresponding Carbon atoms would lower the energy further by increasing the distance between neighbouring non-bonding groups and thus reducing the non-bonded repulsive terms between them. Bends and kinks were also introduced to the ring so as to decrease the overlap of neighbouring substiuents (increasing the dihedral angle, anti-periplanar being an ideal situation)in an attempt to reduce the rings torsional strain. Unfortunately MM2 optimisation returned the same geometries and corresponding energy terms tabulated above.

Next, the outer 6-membered ring was looked at in attempt to further minimise the total energies of the two isomers. Interestingly, it was found that by bending the 6-membered ring away from the larger ring both isomers achieved a lower energy. The steric conflict between the 6-ring bound substituents and those of the main ring will have been reduced, increasing stabilisation. The optimisation of both isomers was improved even further by making this 6-membered ring adopt a more stable chair-like conformation. By improving the structure in these two ways, the total energy of both molecules was reduced by approximately 4 kcal mol-1 .

The saturated form of isomer 9 has a total energy of 53.1 kcal mol-1 and the alkane of isomer 10, 58.5 kcal mol-1 . Each potential energy term is tabulated below with the corresponding conformations illustrated.

| Saturated Isomer | Dipole/Dipole | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 0.00 | 2.84 | 13.5 | 0.659 | 22.0 | -1.28 | 15.3 |

| 10 | 0.00 | 3.11 | 14.4 | 0.590 | 24.3 | 0.0466 | 15.9 |

The fact that the corresponding alkanes are higher in energy and thus less stable gives a simple argument as to why isomers 9 and 10 can be considered stable in their unsaturated forms. The basis for the relative instability of the saturated isomers arises due to repulsive Van Der Waal interactions increasing the strain energy of the large ring. The predominant repulsive interactions which destabilise the saturated isomers are vicinal and transannular interactions between neighbouring Hydrogen atoms inside the large ring. Such interactions are simply a result of substituent overlap of nearby groups in large cyclic compounds much like the simpler but highly unfavourable syn-periplanar overlaps seen in aliphatic alkanes and alkenes. Naturally these unfavourable interactions are exaggerated in the saturated isomers due to the presence of an additional two Hydrogen atoms. The table above shows an increase in non-bonding terms which illustrates the fact that repulsive Van Der Waal interactions are increasing within the molecule (the ring specifically). More importantly however, the increasing torsional strain imposed on both molecules by hydrogenating the alkene bond is supported by the relatively large increase in torsional energy components for both isomers (approximately 3 kcal mol-1 gained on hydrogenation).

In summary, the saturated isomers are sterically and torsionally more strained than their corresponding unsaturated counterparts making the reaction of the double bond thermodynamically unfavourable and less likely. This "unwillingness" to react so as to maintain the lowest possible energy lends these alkenes "hyperstability" with respect to any reagent (Dihydrogen included) that would react with the double bond, in turn removing unsaturation.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

First of all, compound 12 was drawn using ChemDraw3D and then optimised using the MM2 force field. This yielded the following energy terms with a total energy of 17.9 kcal mol-1.

| Molecule | Dipole/Dipole | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialkene | 0.112 | 0.622 | 4.78 | 0.0408 | 7.63 | -1.08 | 5.79 |

Having done this the MOPAC molecular orbital method was used to further optimise the compound's structure. This returned a heat formation of 19.74 kcal mol-1, a value which is in good agreement with the MM2 calculation before it in turn validating these results. The other reason for using such an optimisation method is to view the molecular orbitals formed by the molecule. By inspecting the HOMO of this molecule the most nucleophilic alkene double bond may be deduced. Below is the picture of said molecular orbital.

Rather interestingly this picture suggests that a pi-like molecular orbital between the cyclopropyl bridging carbon and the chlorine atom is formed. The two bonding sp3 hybridised orbitals lying along the bond to the bridging cyclopropyl carbon are inverse in phase with respect to one another. The resultant lobes are then able to correspond to filled p-orbital on the adjacent chlorine atom giving the appearance of a pi-antibonding molecular orbital. This molecular orbital overlaps well with the pi-antibonding molecular orbital of the exo- alkene double bond. This orbital overlap lends a degree of stabilisation to the exo-alkene bond compared to the endo-double bond and as such one can conclude that it will be the endo- bond that will be most reactive (as a nucleophile). This may also be supported by a steric argument whereby it can be assumed that the chlorine atom hinders addition (electrophilic) on the upper face of the exo- alkene bond making it less reactive as a nucleophile compared to the endo- bond.

The HOMO, HOMO-1, LUMO, LUMO+1, LUMO+2 are shown on the right.

As these Molecular Orbital illustrations show, there is a large degree of secondary orbital overlap within this molecule. For this reason, it can be suggested that the heat of formations obtained from the MOPAC calculations may be somewhat higher than reality with the "real" molecules being more stable than calculated by virtue of positive molecular orbital overlap.

Next the corresponding monoalkene in which the double bond anti (see above as to why) to the C-Cl bond has been hydrogenated has been drawn in ChemDraw3D and optimised using the MM2 force field. This returns the following energy terms with a total energy of 22.3 kcal mol-1.

| Molecule | Dipole/Dipole | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoalkene | 0.0705 | 0.914 | 4.65 | 0.0144 | 10.8 | -1.07 | 6.99 |

Next MOPAC optimisation was run yielding a heat of formation of -2.43061 Kcal/Mol.

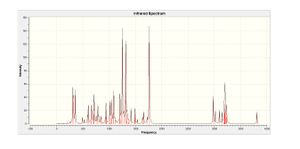

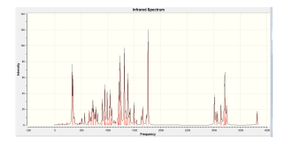

Using the MOPAC optimisations for both the dialkene and monoalkene, the Infra-red spectra of the two may be predicted and the corresponding vibrations analysed.

| Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity |

|---|---|

| 775.0 | 20.0 |

| 1758 | 4.34 |

| Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity |

|---|---|

| 770.9 | 25.1 |

| 1737 | 4.21 |

| 1757 | 3.93 |

In both cases the vibrations observed at approximately 770cm-1 corresponding to the vibrations of the C-Cl bond, specifically a stretching of said bond. The vibrations at approximately 1750cm-1 on the other hand, are the stretches of the C-C double bonds. In the case of the dialkene, the vibration at 1737cm-1 is the stretching of the endo- double bond with the 1757cm-1 corresponding to the exo- double bond (as seen in GaussView). Vibrations at approximately 3100cm-1 corresponding to the stretching of the alkene C-H bonds seems to indirectly stretch the C=C slightly as well. The other vibrations predicted by the program include stretches of the other bonds in the molecule as well as more severe ring distortions.

These results show us then, that the C-Cl bond causes the vibrational frequency of the (exo-) alkene bond to increase. This result supports the molecular orbital argument suggested above as to why the exo- double bond is more stable than the endo- bond. If the exo- bond is more stable due to a good secondary orbital overlap it can be presumed that the exo- alkene bond is stronger than the endo- alkene bond. As such more energy will be required to distort and stretch said bond, resulting in a higher vibrational frequency as is observed.

It is expected that adding electronegative groups (alcohol, amine, halides etc.) will effectively lower the electron density found in these overlapping molecular orbitals as well as in the alkene bond, resulting in a weaker C=C bond and thus lower vibrational frequency. Electropositive substituents (Silyl groups), on the other hand may strengthen the secondary orbital overlap and C=C bond resulting in a higher vibrational frequency.

Mini-Project

The reaction chosen for this mini-project is a diastereoselective Aldol synthesis. The reaction pathway consists of the Lewis-acid catalysed ring-opening of a cyclic ketone to form an enolate, which then reacts with an aldehyde to form the Aldol. The Lewis-acid also acts as a catalyst for the joining of the enolate and aldehyde chains resulting in a 6-membered chair-like transition state. Depending on the conformation of this transition state, either the syn- diastereoisomer or the anti- diastereoisomer may form in the product. By looking at the mechanistic pathway this reaction takes it can be deduced which isomer is most likely to predominate. Any conclusions may then be supplemented with the corresponding geometry optimisations and corresponding MM2 force field calculations. The latter half of this project will focus on using computational techniques to predict various spectra for the two isomeric products and ultimately will be used to decide whether the two isomers can be differentiated through spectroscopic methods. With respect to the 13C NMR, comparison to literature spectral values will aid in validating the power and accuracy in predicting spectra via computational means.

Reaction Scheme and Mechanistic Pathway

Below is the general reaction scheme and corresponding isomeric products that will be studied.

In this reaction TiCl4 is the lewis-acid catalyst and CH2Cl2 the solvent. The fact that this reaction is run at a low temperature suggests that irreversibilty is being imposed so as to kinetically control the reaction (i.e. the product formed fastest will predominate); this will be expanded upon later in the report.

The first step of this mechanism involves the lewis-acid (TiCl4 ) accepting electron density from the cyclic ketone's carbonyl oxygen. This shifting of electron density facilitates the ring-opening of the cyclopropyl group as electrons flow across the chain to appease the carbonyl group's loss of electrons. As the cyclopropyl ring is cleaved open a carbocation is formed β- to the trimethylsilyl group. This is a facile process as the carbocation is stabilised by the silyl-β effect in which the vacant p-orbital of the carbocation is strongly stabilised by the Si-C σ* molecular orbital which is a particularly good donor by virtue of Silicon's electropositivity and thus high energy donor orbitals. The trimethylsilyl group is then cleaved from the molecule so as to quench the carbocation's positive charge resulting in an enolate derivative. A mechanistic summary is provided below.

It is worth noting that at this stage it is entirely possible that the bond between the Oxygen atom and Lewis-acid may break resulting in the formation of an γ,δ-unsaturated ketone. This is a side reaction however and as such will not be focussed on here.

Having formed the enolate derivative it is now free to react with the aldehyde as expected for Aldol formation. It is thought that TiCl4 catalyses this step by associating with the aldehyde carbonyl Oxygen whilst still bound to the carbonyl Oxygen of the enolate derivative. In doing so the Lewis-acid forms a transition-state which brings the two reactants closer together in a conformationally acceptable manner whilst simultaneously stabilising the increased electron density received by the Aldehyde over the course of the addition (electron density resides on carbonyl Oxygen). This transition-state is a 6-membered ring and as such preferentially adopts a chair-like conformation (as opposed to the higher energy boat conformation) [1]. This is illustrated below.

As the illustration shows, depending on the direction from which the Aledhyde is attacked the Phenyl group may either adopt the equatorial position or the axial position; the Hydrogen atom adopting the opposing position. Due predominantly to 1,3-diaxial compressions and steric clashes associated with nearby axial substituents, it is energetically favourable for the larger substituents to adopt the equatiorial position so as to reduce strain on the ring. The Phenyl group corresponding to the enolate derivative adopts the axial conformation due to a favourable anti-periplanar relationship with the σ-orbital occupied by the neighbouring Oxygen atom's lone pair. There is also likely a degree of conformational locking due to the carbon-carbon double bond (preventing ring-flipping and as such interconversion between axial and equatorial positions). Because this Phenyl group adopts the axial conformation there is already a large degree of strain placed on the ring, making the sterics of placing a second Phenyl group into an axial conformation even more unfavourable. It may then be concluded that the transition-state where the Phenyl group is found in the equatorial position will be significantly lower in energy in comparison to the corresponding transition-state where the Phenyl group is placed in the axial position. The formation of product from these transition-states is shown below.

Note: It is assumed that in the final step that TiCl4 has been cleaved and the resultant negative charge (on the Oxygen atom) appeased by proton transfer to form the Aldol.

Because this reaction is carried at out at low temperatures the amount of thermal energy found in the system will be particularly low. The natural consequence of this is that the system will only have enough energy to overcome the activation barrier leading to transition-state formation, effectively making the reaction irreversible (not enough energy to go back to starting materials); this is kinetic control. In a kinetically controlled reaction the product which forms the fastest (i.e. proceeds via a lower energy transition state) will predominate. It is therefore logical to assume that syn-isomer will predominate as the preceding transition-state is more stable (as discussed above). This is in fact the case, as supported by the literature[1] which shows the syn:anti ratio for this particular reaction to be 5:1. If the Phenyl group was replaced by an even bulkier ligand it is possible that the selectivity will be driven such that only the syn-product will be found. The choice of Lewis-acid will undoubtedly affect the formation of the transition-state and as such it can be expected that selectivity may change with a different Lewis-acid as well. The fact that this reaction is kinetically controlled is supported by the MM2 optimisations carried out on both products, the results obtained from this are tabulated below.

| Isomer | Dipole/Dipole | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syn | 0.939 | 1.36 | 4.65 | 0.268 | -6.65 | -4.85 | 17.0 |

| Anti | -0.545 | 1.39 | 3.78 | 0.273 | -7.38 | -3.89 | 16.7 |

The total energy of the syn-isomer is 12.7 kcal mol-1 and 10.3 kcal mol-1 for the anti-isomer. As this highlights, the syn-product is actually higher in energy than the anti-product; further supporting the fact that this reaction is kinetically controlled.

Predicted 13C NMR Spectrum

Having used a mechanistic argument to explain product formation and selectivity, computational methods may now be used to predict the 13C NMR spectra for both isomers and as such it can be concluded whether or not computational chemistry may be used to differentiate between the two diastereoisomers. Using literature spectra, the accuracy of the predicted spectra may be validated. Below are the predicted 13C chemical shifts reference against literature shifts[2]. The literature quotes the solvent used as being deuterated chloroform and as such the prediction was made with the same solvent.

| Predicted Chemical Shift/ppm | Degeneracy | Literature Chemical Shift/ppm |

|---|---|---|

| 35.29 | 0.78 | 31.7 |

| 61.98 | 0.83 | 52.7 |

| 78.58 | 0.91 | 73.7 |

| 112.8 | 0.98 | 116.9 |

| 123.8 | 0.97 | 126.2 |

| 124.2 | 1.9 | 127.5 |

| 124.2 | 0.99 | 128.3 |

| 124.9 | 1.90 | 128.4 |

| 124.9 | 0.99 | 128.6 |

| 127.8 | 0.87 | - |

| 130.1 | 0.97 | 133.3 |

| 134.6 | 0.93 | 135.4 |

| 136.0 | 0.97 | 137.0 |

| 139.5 | 0.99 | 141.7 |

| 196.7 | 0.96 | 204.2 |

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5688

| Predicted Chemical Shift/ppm | Degeneracy | Literature Chemical Shift/ppm |

|---|---|---|

| 35.66 | 0.97 | 34.7 |

| 52.65 | 0.97 | 52.6 |

| 75.37 | 0.86 | 75.5 |

| 116.6 | 0.94 | 117.6 |

| 123.8 | 0.99 | 126.4 |

| 124.0 | 0.99 | 127.9 |

| 124.2 | 0.99 | 128.3 |

| 124.3 | 0.99 | 128.5 |

| 124.4 | 0.99 | 128.6 |

| 124.5 | 1.00 | - |

| 124.5 | 0.99 | 133.3 |

| 126.0 | 0.99 | 135.4 |

| 129.5 | 0.99 | 137.0 |

| 129.8 | 1.00 | 133.2 |

| 133.8 | 0.99 | 134.4 |

| 135.8 | 0.99 | 137.9 |

| 137.3 | 0.99 | 142.4 |

| 197.4 | 0.61 | 204.8 |

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5689

The predicted results compare favourably to the literature values with discrepancies ranging from 1-5 ppm and those at higher chemical shifts deviating slightly more. It can be seen however, that there are fewer literature shifts compared to the predicted results. This would suggest that nuclei spin-coupling is more extensive in reality (resulting in fewer chemical shift readings) and/or the Gaussian used for the prediction was incorrect. This is a minor discrepancy however as most of the correct shifts are observed with values in good agreement with the literature.

Inspection of the results however, shows very little variance in result between the two isomers with the chemical shifts varying by less than 1 ppm between isomers. This leads to the conclusion that 13C wouldn't be a valid means of differentiating between the isomeric products. This form of NMR spectroscopy will only successfully differentiate between more severe cases of isomerism and stereoselectivty.

Whilst computationally predicted 1H NMR spectra are much less accurate and precise, the J3 H-H spin couplings however, can be predicted to a good degree of accuracy. Below are the tabulated values of all of these couplings for both diastereoisomers.

| Hydrogen # (1) | Hydrogen # (2) | J3 H-H Coupling/Hz |

|---|---|---|

| 33 | 32 | 8.22 |

| 32 | 31 | 8.22 |

| 31 | 30 | 8.22 |

| 30 | 29 | 8.22 |

| 34 | 35 | 8.22 |

| 35 | 36 | 8.22 |

| 36 | 37 | 8.22 |

| 37 | 38 | 8.22 |

| 28 | 21 | -0.0318 |

| 21 | 22 | 9.88 |

| 22 | 24 | 1.13 |

| 22 | 23 | 11.1 |

| 23 | 25 | 8.22 |

| 24 | 25 | 1.42 |

| 25 | 26 | 8.22 |

| 25 | 27 | 8.22 |

| Hydrogen # (1) | Hydrogen # (2) | J3 H-H Coupling/Hz |

|---|---|---|

| 33 | 32 | 8.22 |

| 32 | 31 | 8.22 |

| 31 | 30 | 8.22 |

| 30 | 29 | 8.22 |

| 34 | 35 | 8.22 |

| 35 | 36 | 8.22 |

| 36 | 37 | 8.22 |

| 37 | 38 | 8.22 |

| 28 | 21 | -0.267 |

| 21 | 22 | 6.53 |

| 22 | 24 | 3.21 |

| 22 | 23 | 12.3 |

| 23 | 25 | 8.16 |

| 24 | 25 | 0.791 |

| 25 | 26 | 8.22 |

| 25 | 27 | 8.22 |

As expected, the H-H couplings seen in the phenyl groups are all the same. Because the orientations of the Hydrogen atoms don't change (with respect to each other) the nuclei spins will couple in the same way, giving the same coupling constant. To find out other the couplings differentiate between the two isomers one must look at the couplings corresponding to the branched unsaturated alkyl group. Doing so shows that the coupling constants in the syn-isomer are smaller than those of the anti-isomer. Whilst the difference is relatively small (approximate difference of 2-3 Hz) it may still be possible that this difference could be registered and noticed using a higher resolution NMR spectrometer. Given the sensitivity of NMR with respect to orientation and nucleic environment (particularly with regard to Hydrogen atoms) it is no surprise that the two isomers give slightly different coupling constants. It is confirmed by the literature that the 1H NMR was in fact used to differentiate between the two isomers and hence the observed ratio between the two. Whilst it is not specified as to whether the two isomers were distinguished by chemical shift, relative intensities or coupling constants; it may still be concluded that proton NMR is a good means of distinguishing between diastereoisomers.

An extension of this would be HH COSY (Correlation spectroscopy) which effectively correlates proton coupling to chemical shift. This method is particularly good for studying more subtle Hydrogen relationships such as vicinal and geminal interactions (torsional interactions) and w-coupling (long range proton coupling, normally extending across 4 or 5 bonds). Another proton-based NMR method is NOESY (Nuclear-Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy)which is similar to COSY except it considers the changing energy levels of the protons arising from coupling and the corresponding intensity changes. The literature confirms that this form of NMR spectroscopy was used to distinguish between the two isomers. COSY and NOESY spectra would be very difficult to predict using computer-based models however, limiting its practical use.

Predicted Infra-red Spectrum

| Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity |

|---|---|

| 1247 | 144 |

| 1319 | 125 |

| 1763 | 147 |

| 2983 | 41.7 |

| 3202 | 61.7 |

| Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity |

|---|---|

| 1229 | 87.2 |

| 1307 | 97.1 |

| 1382 | 64.4 |

| 1761 | 120.7 |

| 3011 | 38.7 |

| 3204 | 65.9 |

For the syn-isomer the lower vibrational frequencies correspond to general distortions across the molecule manifesting in an apparent "swaying" of the alkyl Hydrogen atoms in the molecule. The vibrations at approximately 1760cm-1 refer to the stretching of the carbonyl bond and those at approximately 3000cm-1 and 3200cm-1 corresponding to stretching of the Phenyl C-H bonds. Much higher vibrations (approximately 3600cm-1 ) were also noted in the data logs (less apparent in the spectra). These vibrations correspond to the alcohol functional group found in both molecules.

The IR spectrum and corresponding vibrations seen in the anti-isomer are very similar with the vibrations observed for the syn-isomer also seen for the anti-isomer. It is interesting to note however, that an additional vibration (of significant intensity) was seen for the anti-isomer at 1382cm-1 . According to GaussView this vibrational mode corresponds to a similar Hydrogen atom "wagging" as described before however this time the distortion extends to the Hydrogen atoms in the Phenyl group nearest to the carbonyl group. When viewing the 2 isomers in ChemDraw3D it can be seen that in the anti-isomer the unsaturated alkyl chain is in the same plane as the nearby aromatic ring, this is not the case for the syn-isomer on the other hand which shows staggering of the two. If the alkyl chain in the anti-isomer is in the plane of the aromatic ring then the vibrational distortions may extend along to the aromatic ring hence resulting in the wagging of the Phenyl Hydrogen atoms as well. With the syn-isomer though, the two groups are poorly aligned and as such the vibrations do not extend as far as the aromatic ring.

With that in mind it may be concluded that IR/vibrational spectroscopy is also a good method for determining between diastereoisomers.

Predicted UV/Visible and Circular Dichroism Spectra

As the two UV/Vis spectra on the right illustrate, both isomers strongly absorb in the Ultra-Violet region of the electromagnetic spectrum with no absorption and correspondingly, no emission of visible light. The region in which the two isomers absorb is approximately the same in each case with similar absorption intensities. This unfortunately means that for these two isomers, UV/Vis spectroscopy is a invalid method for distinguishing between the two.

The CD spectrum for the syn-isomer corresponds to its UV/Vis spectrum by showing that a change in absorption occurs at approximately 200nm. Unfortunately the calculation run yielded no CD spectrum for the anti-isomer and as such there is no way of telling if there would be a appreciable difference between the two isomers. The two products are not enantiomers however so it is predicted that the CD spectra would look identical to one another. This form of spectroscopy is therefore unlikely to prove useful in isomer determination.

Based on computationally derived results it can be concluded that both 1H NMR (and COSY and NOESY in a real lab experiment) and IR spectroscopy are valid means of differentiating between the two diastereoisomers produced in this reaction. 13C NMR, UV/Vis and CD spectroscopy on the other hand are invalid means of differentiating between the isomeric products of this reaction.

References and Citations

[1]V. K. Yadav, R. Balamurugan, Diastereoselective Aldol Reactions of Enolates Generated from Vicinally Substituted Trimethylsilylmethyl Cyclopropyl Ketones, Organic Letters, Vol. 5, Issue 23, 2003.

[2]V. K. Yadav, R. Balamurugan, Diastereoselective Aldol Reactions of Enolates Generated from Vicinally Substituted Trimethylsilylmethyl Cyclopropyl Ketones, Organic Letters Supporting Information, http://pubs.acs.org/doi/suppl/10.1021/ol035481g/suppl_file/ol035481gsi20030923_062533.pdf , 2003

[3]B.Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447.

[4]E. Breitmaier, Structure Elucidation by NMR in Organic Chemistry A Practical Guide, 1993, pp.31-32, 54.

[5]S. R. Buxton, S. M. Roberts, Guide to Organic Stereochemistry from methane to macromolecules, 1996, pp. 64.

[6]A. K. Rappe, C. J. Casewit, Molecular Mechanics across Chemistry, 1997, pp. 4-9, 34-40.