Rep:Mod:jag

Module 3

Introduction

The modelling of transition states is a very useful technique in chemistry as it allows the prediction of mechanistic product formation and reaction rates. Computational chemistry allows chemists to investigate the potential energy and optimal structures of these transition states, hence greatly increasing the knowledge and understanding in this field.

In the following project, two important organic reactions (Cope Rearrangement and Diels Alder reaction) will be examined using GaussView 5.0. This computer program works by utilising quantum mechanics, with enforcement of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, to produce potential energy surfaces for a given reaction. This involves plotting energy against the reaction coordinate, which is defined by the intermediates and transition states of the reaction. The potential energy surface is then used to characterise the progress of a reaction and frequency analysis gives information about vibrational modes of the molecules. A graphical example of a potential energy surface is provided below [1] (where the minima are reactancts/products and the maxima represent transition states/saddle points) :

Cope Rearrangement

The Cope rearrangement is a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, which involves the heating of a 1,5-diene. It involves the movement of pi electrons, with the breaking and formation of a sigma bond. The reaction mechanism is shown below [2]:

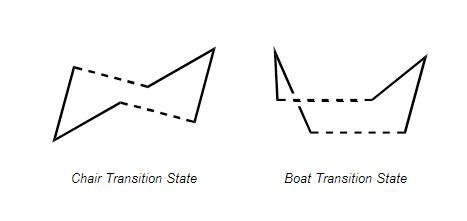

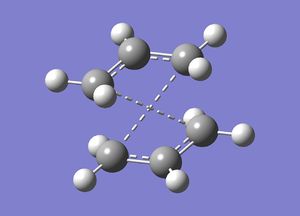

There are two possible transition states that the reaction could proceed via - a chair or boat conformation (shown below [3]). This project will involve optimisation and frequency calculations to find the correct transition state for the reaction.

Comparison of 1,5-Hexadiene Conformers

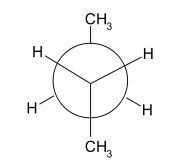

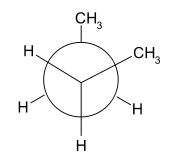

1,5-Hexadiene has two dominant conformations which are anti-peri planar and gauche. The difference between these two conformers can be most easily seen using Newman projections (shown below [4]). The left diagram displays an anti-peri planar arrangement, with the most bulky substituents, the methyl groups, being as far apart as possible, a dihedral angle of 180 degrees. The right hand diagram is an example of a gauche conformation, with the methyl groups being next to each other, a dihedral angle of 60 degrees.

Optimisation of the 1,5-hexadiene molecule will enable investigation into all the different anti-peri planar and gauche conformers, which can then be characterised according to their energy. A table was provided to me, containing all of the different possible conformations, which I have included.

Anti

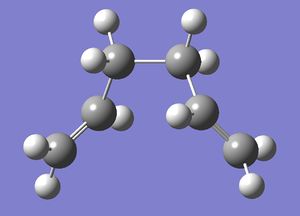

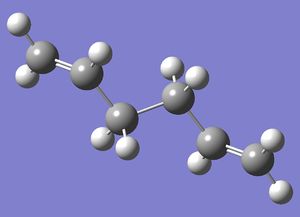

1,5-Hexadiene was drawn with an anti-peri planar arrangement and then "cleaned up" and optimised. The optimised structure (shown right) is point group C2.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24055

| Anti optimisation | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RHF | |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | |

| Total Energy | -231.69260235 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00001824 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.2021 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

Gauche

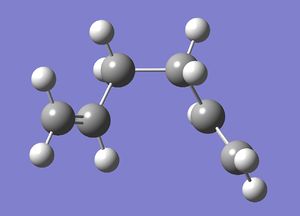

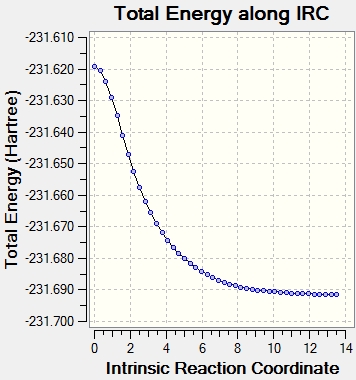

The Gauche conformer, in the same way as for the anti-peri planar arrangement, was "cleaned up" and optimised. The resulting structure (shown right) is point group C2.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24058

| Gauche optimisation | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RHF | |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | |

| Total Energy | -231.68771613 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00001461 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.4550 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

The gauche conformation has a higher (less negative) energy than the anti-peri planar form, which shows that it is the less stable conformer. This is due to the steric clash of the two C=C groups, which does not occur in the anti-peri planar arrangement.

Lowest Energy Conformer

The table which was provided to me (shown below) has been used as reference to carry out the optimisations of the different conformations. It can be seen that the lowest energy is the gauche 3 form, with the anti 1 and 2 arrangements also being very close in energy to this. These two anti-peri planar arrangements are low in energy due to the orbital stabilisation in this orientation and the bulky R groups being the maximum distance away from each other (180 degrees). Gauche 3 is the most stable form because in this orientation there is maximum attractive Van der Waals interacion between the hydrogens, with restricted Pauli repulsion from neighbouring σ C-H orbitals.

ci conformer

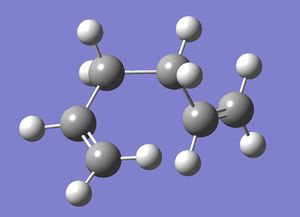

The ci conformer was drawn and then optimised at the HF/3-21G level, followed by the DFT/6-31G(D) level.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24060

| ci conformer optimisation 3-21G | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RHF | |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | |

| Total Energy | -231.69253516 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00004313 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0000 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24077

| ci conformer optimisation 6-31G(D) | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RHF | |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(D) | |

| Total Energy | -234.61170273 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00001299 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0000 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

Literature value for optimised energy: -234.32879 a.u. This is only a slightly higher energy than the calculated values, showing a good general agreement.

Frequency analysis was used to check the minimum on the potential energy surface, by ensuring that all vibrational modes are real and a positive frequency.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24087

| ci conformer frequency analysis | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(D) | |

| Total Energy | -234.61170273 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00001300 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0000 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

Low frequencies --- -18.8144 -11.7181 -0.0012 0.0003 0.0005 1.7516 Low frequencies --- 72.7146 80.1401 120.0114

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000036 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000013 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000222 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000104 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.485397D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Zero-point correction= 0.142491 (Hartree/Particle) Thermal correction to Energy= 0.149847 Thermal correction to Enthalpy= 0.150791 Thermal correction to Gibbs Free Energy= 0.110881 Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469212 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461856 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.460912 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500822

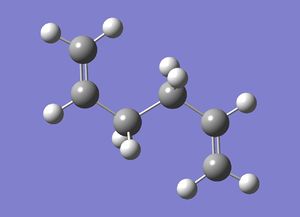

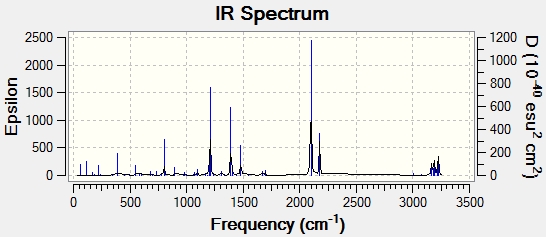

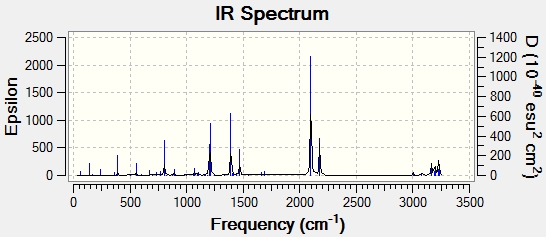

There are 41 vibrations in total, of which 21 are IR active (there is a change in dipole moment) and so can be seen in the IR spectrum.

Optimizing the Chair and Boat Transition Structures of the Cope Rearrangement

The difficulty in optimising a transition state is that the geometry of the structure needs to be known in advance to a fair degree of accuracy, so that the calculations can converge correctly on the potential energy surface. In any cases where this is difficult to compute, the GaussView program may provide a different structure to the one required.

Chair Transition state

Hessian Method

Two allyl fragments were optimised and placed in an orientation similar to that of the chair conformation, about 2.2A apart. This combined structure was then further optimised.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24106

| Allyl fragment | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | UHF | |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | |

| Final Energy | -115.82303991 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00009674 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0293 Debye | |

| Spin | Doublet | |

| Point group | C1 | |

| Job CPU Time | 17.4 seconds. | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000160 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000056 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000711 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000290 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.860815D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24109

| Combined alyll fragments | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RHF | |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | |

| Final Energy | -231.61932178 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00004102 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0009 Debye | |

| Imaginary freq | 1 | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Point group | C1 | |

| Job CPU Time | 18.4 seconds. | |

Low frequencies --- -817.8541 -2.2760 -0.0006 -0.0003 0.0004 5.5533 Low frequencies --- 6.9292 209.5850 395.4710

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000037 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000009 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001791 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000308 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.772348D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The frequency analysis produced the expected imaginary absorption peak at -817.85 cm-1. This negative absorption is typical of a transition state and shows that the structure is at a maximum point on the potential energy surface. The peak corresponds to the breaking and forming of the sigma bond in the Cope rearrangement reaction. The spectrum below displays the IR active vibrations,

Frozen Coordinate Method

If the geometry of a transition state is not known to a high level of accuracy, the potential energy surface may distort to give a different curvature, and so converge to a structure which is not the desired transition state. A way to try to avoid this is to use the frozen coordinate method. This method involves freezing the reaction coordinate and minimising the energy of the rest of the molecule by optimising it, followed by unfreezing of the reaction coordinate and optimisation of the whole transition state. In the case of the Cope rearrangement, it is the breaking/forming sigma bond that is frozen, whilst the rest of the molecule is optimised.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24114

| Frozen coordinate part 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RHF | |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | |

| Total Energy | -231.61509647 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00329464 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0014 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000011 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000003 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000478 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000081 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.759566D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24116

| Frozen coordinate part 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RHF | |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | |

| Total Energy | -231.61932178 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00004102 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0009 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

Low frequencies --- -817.8541 -2.2760 -0.0007 -0.0003 0.0000 5.5533 Low frequencies --- 6.9292 209.5850 395.4710

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000037 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000009 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001791 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000308 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.772348D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Boat Conformation

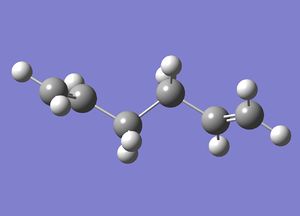

For the boat transition state, two molecules of the optimised ci 1,5 hexadiene (anti 2) conformation were numbered so that one of the molecules represented a reactant and the other a product. HF/3-21G method was used to carry out the calculation with "Opt+Freq" settings and "QST2" optimisation. The resulting optimisation (shown right) failed; although gaussian has been able to locate a transition state of sorts, it is not of the correct geometry, ie. in boat form. This is due to the inability of GaussView to rotate the bonds to form the required orientation.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24120

| QST2 method part 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RHF | |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | |

| Total Energy | -231.61932228 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00004348 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0000 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000038 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000017 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000616 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000225 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.987172D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

In order to correct this failure, the bond angles of the input structure were manually altered, to provide an initial structure more similar to the desired boat conformation. For both the reactant and product molecules, the central dihedral angle was set to 0 degrees and the inner C-C-C angle was set to 100 degrees, providing a structure more similar to the boat form. The calculation was then run again, with the same settings as before, producing a successful transition state (shown right).

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24123

| QST2 method part 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RHF | |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | |

| Total Energy | -231.60280239 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00003238 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.1584 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

Low frequencies --- -839.9283 -8.0756 -6.3114 -4.0796 0.0006 0.0009 Low frequencies --- 0.0012 155.0909 382.2138

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000105 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000022 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001248 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000277 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.838289D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

There is an imaginary frequency at -839.9283 which shows that the structure is a transition state because it is a maxima on the potential energy surface. The spectrum below displays the IR active vibrations.

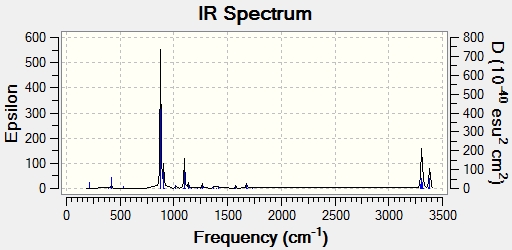

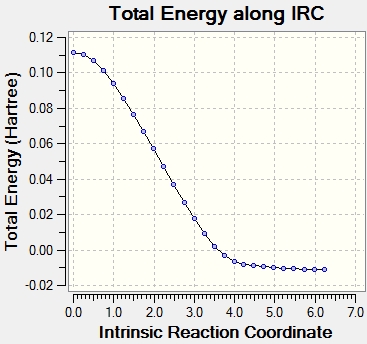

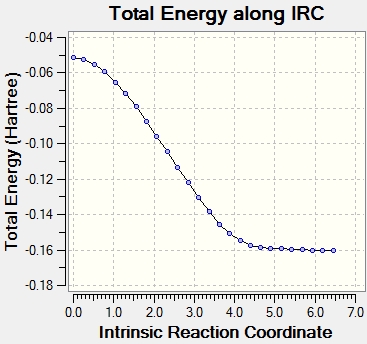

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24215

The Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) is the pathway of minimum energy from a transition state to the reactants or products. The IRC method follows the minimum energy path from a transition state to a minimum on the potential energy surface, which corresponds to the reactant or product. This enables the identification of the conformation which results from a specific transition state structure. The IRC method works by taking small increments down the energy surface with the steepest gradient. The IRC path can be designated a direction; forwards, backwards, or in both directions. In this case, due to the reaction pathway being symmetrical in both directions, it was chosen as "forwards" only. The number of points along the IRC was set as 50.

| ci conformer optimisation 6-31G(D) | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | |

| Calculation Type | IRC | |

| E(RHF) | -231.61932242 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00002671 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0002 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Point Group | C1 | |

| Job cpu time | 14 minutes 43.5 seconds. | |

The IRC did not reach the minimum energy geometry using 50 steps, so the calculation was performed again using 100 steps instead, which enabled a minimum energy to be found. The resulting structure resembles the C2 conformer (gauche 2).

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24220

| ci conformer optimisation 6-31G(D) | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | |

| Calculation Type | IRC | |

| E(RHF) | -231.61932242 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00002671 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0002 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Point Group | C1 | |

| Job cpu time | 15 minutes 13.3 seconds. | |

Activation Energies

Both the chair and boat transition states were calculated using the higher order optimisation: B3LYP/6-31G

Chair Optimization

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24145

| Chair optimisation | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(D) | |

| Total Energy | -234.55698536 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00016636 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0008 Debye | |

| Charge | 0 | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000191 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000049 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001348 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000311 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.259402D-06

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Boat Optimisation

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24142

| Boat optimisation | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(D) | |

| Total Energy | -234.54309307 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00000117 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0613 Debye | |

| Charge | 0 | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

Low frequencies --- -530.2936 -8.9971 -0.0012 -0.0010 -0.0009 15.4361 Low frequencies --- 17.6170 135.5780 261.6528

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000002 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000001 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000024 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.663302D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The data in the table below shows the chair conformer to have a more negative energy than the boat form, for both the HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G(D), due to it being more stable. For all values, the zero-point energy at 0K is smaller than the sum of electronic and thermal energies, which is in agreement with theory because there are no thermal vibrations at 0K. At the higher B3LYP/6-31G(D) level, the calculated value is significantly closer to the experiental value and is even within the experimental range for the chair transition state at 298K. This high degree of accuracy shows that computational calculations can indeed be a very useful tool in modern chemistry.

1 a.u. = 1 hartree = 627.509 kcal/mol

Total energies after optimisation

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy (a.u.) | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies at 0 K (a.u.) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies at 298.15 K (a.u.) | Electronic energy (a.u.) | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies at 0 K (a.u.) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies at 298.15 K (a.u.) | |

| Chair TS | -231.619322 | -231.466705 | -231.461346 | -234.556983 | -234.414919 | -234.408998 |

| Boat TS | -231.602802 | -231.450929 | -231.445300 | -234.543093 | -234.402340 | -234.396006 |

| Reactant (anti2/Ci) | -231.692535 | -231.539539 | -231.5322566 | -234.611710 | -234.469203 | -234.461856 |

Activation energies

| HF/3-21G at 0 K (ΔE (kcal/mol)-1) | HF/3-21G at 298.15 K (ΔE (kcal/mol)-1) | B3LYP/6-31G* at 0 K (ΔE (kcal/mol)-1) | B3LYP/6-31G* at 298.15 K (ΔE (kcal/mol)-1) | Experimental Values [4](ΔE(kcal/mol)-1) | |

| ΔE (Chair) | 45.7 | 45.3 | 34.1 | 33.7 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat) | 55.6 | 50.3 | 42.0 | 37.6 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

The Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

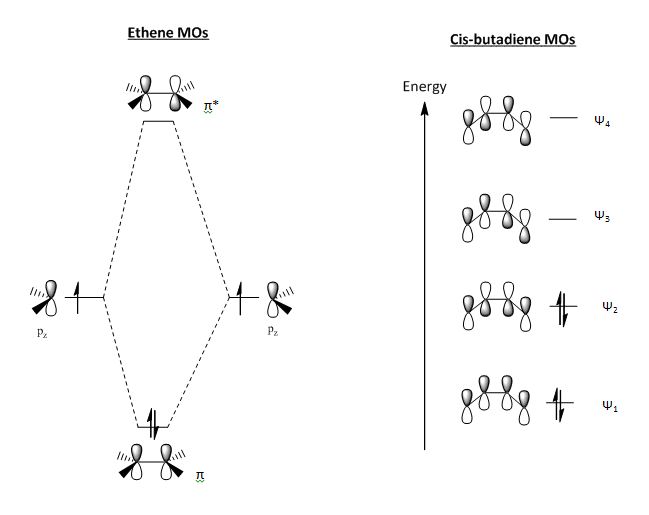

The Diels-Alder reaction is a well known [4+2] cycloaddition which occurs between a conjugated diene and a dienophile. It is a useful and popular reaction for forming carbon-carbon bonds due to it being both regioselective and stereoselective. The reaction is determined by the orbital interactions between the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile. The rate of the reaction can therefore be increased by the inclusion of an electron withdrawing group (EWG) on the dienophile, which lowers the energy of the π* LUMO, promoting electron donation into it from the diene's HOMO (shown below [5])

There are two Diels-Alder reactions which are going to be investigated in this project: the reaction of ethylene with cis-butadiene and maleic anhydride with cyclohexa-1,3 diene.

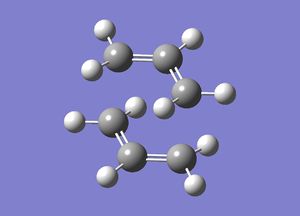

The Reaction of Ethylene with cis-Butadiene

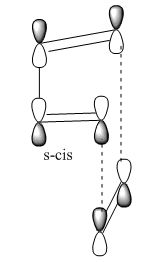

As with all diels-alder reactions, this is a concerted pericyclic reaction, which involves the breaking and formation of a sigma bond. It requires the butadiene fragment to be in the cis conformation, rather than the trans, where there would be insufficient orbital overlap. The molecular orbitals have been generated below to display the stereo and regio chemistry of the reaction.

The reaction proceeds via a transition state with an envelope structure. In order to investigate this, the diels-alder fragment was produced and the molecular orbitals visualised.

Diels Alder Fragment

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24187

| Diels Alder fragment | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RAM1 | |

| Basis Set | ZDO | |

| E(RAM1) | 0.04879719 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00001745 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0414 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

| Point group | C2 | |

| Job CPU Time | 22.6 seconds. | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000030 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000011 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000341 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000162 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.691126D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

| Molecular Orbital | Molecular Orbital Schematic | Symmetry of MO | Energy (au) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO |  |

Anti-symmetric | -0.34381 |

| LUMO |  |

Symmetric | 0.01707 |

The HOMO of cis-butadiene contains a node, which destabilises the orbital with respect to the lower lying orbitals, raising its energy. The LUMO contains two nodes, and has overall anti-bonding character.

There is a large HOMO-LUMO gap for both cis-butadiene and ethene, which is difficult to overcome and so requires the correct orbital overlap; cis-butadiene is around 242.7 kCal Mol-1 and ethene is around 276.5 kCal Mol-1. The HOMO of cis-butadiene and the LUMO of ethene are both of the same symmetry (asymmetric) and similar in energy, as are the HOMO of ethene and the LUMO of cis-butadiene. The relative energy difference of the ethene HOMO with the cis-butadiene LUMO is 0.40484 au and the energy difference of the cis-butadiene HOMO with the ethene LUMO is 0.39665 au. These energy differences have very similar values, with the latter being slightly more favourable. In order to determine with a greater degree of certainty which interaction is taking place, further calculations were performed.

Diels Alder transition state

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24188

| Diels Alder transition state | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RAM1 | |

| Basis Set | ZDO | |

| Total Energy | 0.11165466 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00001713 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.5604 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

Low frequencies --- -956.0739 -4.4300 -3.9713 -3.4554 -0.0032 0.0140 Low frequencies --- 0.0370 147.1503 246.6411

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000039 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000006 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000983 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000159 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.732848D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

There is an imaginary vibrational mode at -956.07cm-1, typical of a transition state and shows that the structure is at a maximum point on the potential energy surface. This vibration corresponds to a symmetrical bending motion.

| Molecular Orbital | Molecular Orbital Schematic | Energy (au) |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO |  |

-0.32396 |

| LUMO |  |

-0.02316 |

The HOMO is symmetrical and weakly bonding. The LUMO is anti-symmetric with more nodes present, making it more antibonding in character.

The reaction proceeds in the manner that it does due to the movement of electrons into low lying pi* orbitals, where there is maximum favourable orbital overlap, forming the structure that is the most energetically stable.

In the transition state, the partially formed sp2 bond of cyclohexene had a length of 1.3975 A (literture [8] = 1.3305 A) and the partially formed sp3 bond had a length of 1.3829 A (literature [8] = 1.454 A). Both of these bond lengths are very similar to each other and lie between the values for normal a C=C bond and C-C bond. This implies that there is delocalisation of the pi electrons and aromatic character present, which is concerted with the concerted nature of pericyclic reactions.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24297

| Diels-alder IRC | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | |

| Calculation Type | IRC | |

| E(RAM1) | 0.11165470 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00003308 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.5605 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

| Point Group | C1 | |

| Job cpu time | 1 minutes 11.4 seconds. | |

Maleic Anhydride

The reaction of maleic anhydride with cyclohexadiene (shown below [6]) can produce either the endo or exo product. The endo product is defined by literature to be the kinetically favoured form, with the exo product being thermodynamically favoured. The kinetic preference for the endo product is due to the lower energy barrier in the transition state, as a result of more favourable orbital interactions.

Firstly, the maleic anhydride and cyclohexadiene were optimised with a 6-31G(D) basis set.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24190

| Maleic Anhydride | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(D) | |

| Total Energy | -379.28954412 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00011731 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 4.0749 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000292 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000094 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001546 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000551 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-4.590502D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

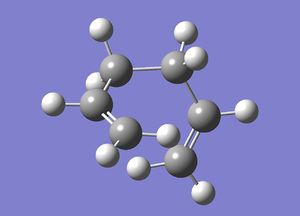

Cyclohexadiene

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24191

| Cyclohexadiene | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(D) | |

| Total Energy | -233.41891073 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00003729 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 0.3780 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000038 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000014 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000621 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000227 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-6.689732D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The HOMO of maleic anhydride is largely bonding, whereas the LUMO has a greater number of nodes and is more antibonding. The LUMO of cyclohexadiene is symmetrical and largely antibonding, with many nodes, whereas the HOMO has mostly bonding character.

The HOMO of cyclohexa-1,3-diene, is symmetrical with a central node and is overall weakly bonding in nature. The LUMO is also symmetrical, but is overall antibonding with several nodes.

Endo

The structure of the transition state leading to the endo product was guessed and drawn in GaussView, with the C-C bonds set as 2.2 A apart and the molecules were optimised.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24240

| Endo frozen coordinate | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | |

| Calculation Method | RAM1 | |

| Basis Set | ZDO | |

| Total Energy | -0.05238801 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00271829 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 6.0017 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000023 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000006 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001628 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000399 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-6.090212D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

There is an imaginary vibrational mode at -806.17cm-1, typical of a transition state and shows that the structure is at a maximum point on the potential energy surface. The spectrum below displays the IR active vibrations.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24247

| Endo optimisation | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RAM1 | |

| Basis Set | ZDO | |

| Total Energy | -0.05150456 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00003499 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 6.1669 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000104 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000013 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001413 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000207 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.538005D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24254

| Endo IRC | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | |

| Calculation Type | IRC | |

| E(RAM1) | -0.05150456 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00003503 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 6.1667 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

| Point Group | C1 | |

| Job cpu time | 1 minutes 44.1 seconds. | |

An IRC was calculated with 100 points, using a semi-empirical/AM1 method.

Activation energy = 68.70 kcal/mol.

Exo

In the same way as was done for the endo form, the structure of the transition state leading to the exo product was guessed and drawn in GaussView, with the C-C bonds set as 2.2 A apart and the molecules were optimised.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24254

| Exo frozen coordinate | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RAM1 | |

| Basis Set | ZDO | |

| Total Energy | -0.05098777 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00229068 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 5.3789 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000043 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000011 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001340 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000313 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.195490D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

There is an imaginary vibrational mode at -811.20cm-1, typical of a transition state and shows that the structure is at a maximum point on the potential energy surface. The spectrum below displays the IR active vibrations.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24271

| Exo optimisation | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |

| Calculation Method | RAM1 | |

| Basis Set | ZDO | |

| Total Energy | -0.05041993 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00003794 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 5.5625 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000038 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000006 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001097 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000153 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy= 8.415632D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/24276

| Exo IRC | ||

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | |

| Calculation Type | IRC | |

| E(RAM1) | -0.05150456 a.u. | |

| Gradient | 0.00003503 a.u. | |

| Dipole Moment | 6.1667 Debye | |

| Spin | Singlet | |

| Charge | 0 | |

| Point Group | C1 | |

| Job cpu time | 2 minutes 16.4 seconds. | |

An IRC was calculated with 100 points, using a semi-empirical/AM1 method

Activation energy = 68.19 kcal/mol, lower than exo transition state

| Endo HOMO | Endo LUMO | Exo HOMO | Exo LUMO |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Secondary orbital overlap [7]

The IRC calculations show that the exo transition state (-0.05042 au) is slightly higher in energy than the endo (-0.05151 au). The additional stabilisation is due to the secondary orbital overlap present in the endo form of the transition state, which is not in the exo. This favourable orbital interaction lowers the energy barrier that has to be overcome in the endo form, rendering it the kinetic product of the reaction and also the predominant form in this case.

Conclusion

This project shows how molecules can be modelled, optimised and analysed effectively using coputational chemistry. In particular, this module has shown that orbital symmetry is conserved in Diels-alder cycloadditions. The HOMO and LUMOs of the reactants and transition states have been investigated in detail, aswell as the regio chemistry of the system. Computatinal chemistry, using programs such as GausView allows this to happen, without needing to do the experiment manually.

Possible improvements

Solvent effects, temperature and pressure were all ignored in these calculations. An improvement in this study would have been to explore the effects of these factors. Running calculations using a greater variety of settings (methods, basis sets etc) would also help provide more information about the reaction systems.

References

1. ↑ Nature Chemistry 4, 169–176 (2012) doi:10.1038/nchem.1244

2. ↑ A.C. Cope, E.M. Hardy, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1940, 62, 441–444

3. ↑ R.B. Woodward, R. Hoffmann, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1969, 8, 781–853

4. ↑ R. Hoffmann, R.B. Woodward, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87, 4388-4389

5. ↑ I. Fleming, Frontier Molecular Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions, 1976

6. ↑ O. Wiest, K. A. Black, K. N. Houk, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116, 10336-10337

7. ↑ R. Hoffman, Organic Chemistry: An Intermediate Text, 2004, John Wiley & Sons

8. ↑ R. Gleiter, M. C. Böhm, Pure & Appl. Chem., 1983, 55, 237—244