Rep:Mod:jacz2

Week 1 - Molecular mechanics and semi-empirical molecular orbital methods for structural and spectroscopic evaluations

Leung, Jackie Tsun Kei (00636554) Year 3 Computational Lab Module 1

Part.1.1 - Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

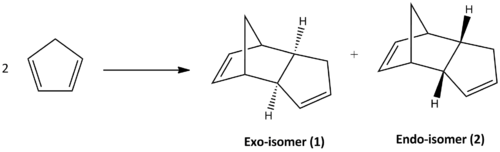

Cyclopentadiene molecules can undergo π4s + π2s cycloaddition with itself to form a dimer. The possible products are the two isomers described in Scheme 1 and experimentally under room temperature and pressure the endo-isomer (2) is observed to be the favoured product.

The selectivity of a reaction is dependent either on the thermodynamic or kinetic control. Reactions that are thermodynamically controlled establishes an equilibrium that is reversible under specific reaction conditions where it is related to the stability of the product. Whereas kinetically controlled reactions depends on the stability of the transition state that has a lower activation energy barrier, which is irreversible and often proceeds faster. One can analyse the molecular mechanics of both isomers to calculate the energies in order to define the thermodynamic and kinetic products respectively.

The optimsations of isomer 1 and 2 were performed using ChemBio3D Ultra 12.0 software using MM2 forcefield and the outcomes are tablulated in Table.1.

| Iteration of energy | exo-isomer(1)

(kcal/mol) |

endo-isomer(2)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2850 | 1.2515 | 0.0335 |

| Bend | 20.5806 | 20.8470 | -0.2664 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.8377 | -0.8359 | -0.0018 |

| Torsion | 7.6548 | 9.5109 | -1.8561 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.4160 | -1.5435 | 0.1275 |

| 1,4 VdW | 4.2322 | 4.3200 | -0.0878 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.3775 | 0.4476 | -0.0701 |

| Total Energy | 31.8765 | 33.9975 | -2.1210 |

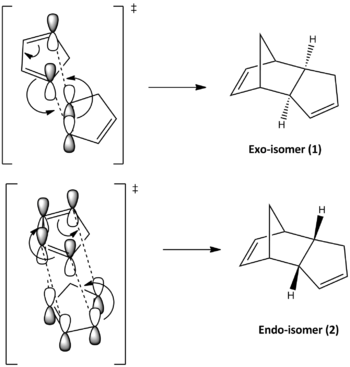

From Table.1 it can be observed that the isomers have a total energy difference of ~2.1 kcal/mol, where the exo-isomer possesses greater stability. This suggests that exo-isomer is formed under thermodynamic control; however it is not the observed major product at room temperature and pressure. Thus the Diels Alder dimerisation reaction of cyclopentadiene can be concluded to be kinetically controlled. The reason of this can be rationalised by the frontier orbital overlap of the transition state of formation of endo-isomer, described by Scheme.2. As shown the endo transition state allows additional orbital overlaps, 2 more pi-orbital interactions compared to the exo-isomer, which provides extra stabilisation lowering its activation barrier and therefore it is the predominant product. This tends to happen quickly at low temperatures like room temperature, since the dimerisation is kinetically controlled. As heat energy is introduced the molecule receives enough energy to revert and form the more thermodynamically stable exo-isomer.

Part.1.2 - Hydrogenation of endo-Cyclopentadiene Dimer

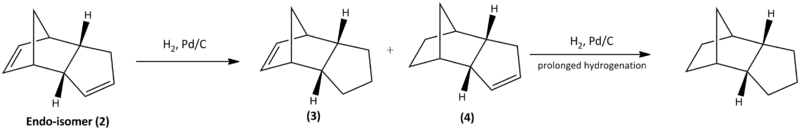

The endo-isomer can be hydrogenated to form the dihydro derivatives (3) and (4), only under prolonged hydrogenation the molecule will be saturated to produce the tetrahydro derivative as shown in Scheme.3. The minimised energies of (3) and (4) are calculated using ChemBio3D ultra 12.0 software with MM2 forcefield, in order to define the more stable product. The obtained energies are tabulated in Table.2.

| Iteration of energy | (3)

(kcal/mol) |

(4)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2771 | 1.0968 | 0.1803 |

| Bend | 19.8664 | 14.5224 | 5.344 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.8346 | -0.5488 | -0.2858 |

| Torsion | 10.8068 | 12.4993 | -1.6925 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.2257 | -1.0688 | -0.1569 |

| 1,4 VdW | 5.6330 | 4.5107 | 1.1523 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1621 | 0.1406 | 0.0215 |

| Total Energy | 35.6850 | 31.1522 | 4.5328 |

Table 2 has shown that molecule 4 has a lower energy than 3 by ~4.5 kcal/mol. Most of the different types of energy between 3 and 4 reveal not much difference; the greatest contribution to the total energy difference is the bending energy, which is related to the strain arised from the bond angles between C-C=C that contains the unsaturated double bonds across the rings, according to the detailed MM2 reports. Unsaturated carbon centres are sp2 which has an ideal angle of 120o, the hydrogenation across double bonds on 3 or 4 can reduce the strain in the rings which are clearly not at the ideal angle. Since one of the five membered ring has a bridge to another ring (norbornene), the double bond on that ring experiences extra strain than the other. Therefore molecule 4 would be lower energy than molecule 3 as the more strained double bond is hydrogenated resulting in more relief and lowering in energy. This is consistent with the computed results shown in Table.2. Literature shows that molecule 3 is not observed to be formed, possibly due to the high energy barrier. The formation of 4 is found to be correlated only to its concentration, which means although it is thermodynamically more favourable, at room temperature the reaction is still under kinetic control. The adsoption and desorption processes are considered to be the rate limiting steps which happens slowly and is dependent on the concentration of reactant, alongside with the high energy barrier of the less strained double bond, this explains the further hydrogenation requires prolonged time to take place.

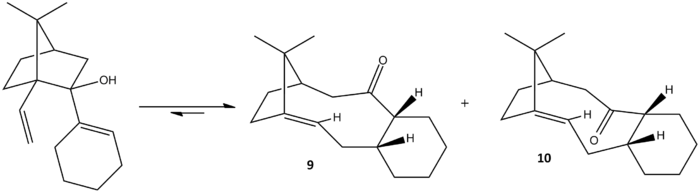

Scheme 4 shows the reaction of oxy-cope arrangement of an alcohol to a pair of atropisomers as molecule 9 and 10, which has the carbonyl group pointing up and down respectively. The atropisomers can be distinguished and isolated due to the hindered rotation about the single bond where there is steric strain. The favoured conformation under thermodynamic control is deteremined by calculating the minimised energy of both 9 and 10 using MM2 and MMFF94 forcefield. 1

| Iteration of energy | (9)

(kcal/mol) |

(10)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.5907 | 2.6012 | -0.0105 |

| Bend | 11.4078 | 10.4225 | 0.9853 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.3571 | 0.2905 | 0.0666 |

| Torsion | 20.9470 | 19.3704 | 1.5766 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.4070 | -2.2165 | -0.1905 |

| 1,4 VdW | 13.9037 | 12.9218 | 0.9819 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.7110 | -2.0092 | 0.2982 |

| Total Energy | 45.0881 | 41.3808 | 3.7073 |

| Iteration of energy | (9a)

(kcal/mol) |

(10a)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.7603 | 2.7065 | 0.0538 |

| Bend | 13.3191 | 11.8225 | 1.4966 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.5765 | 0.3914 | 0.1851 |

| Torsion | 22.3562 | 22.8856 | -0.5294 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.4700 | -1.9870 | 0.5170 |

| 1,4 VdW | 14.3433 | 14.3341 | 0.0092 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.6814 | -1.9973 | 0.3159 |

| Total Energy | 50.1040 | 48.1579 | 1.9461 |

From table 3 the MM2 forcefield calculated energies show clearly that atropisomer 10 is lower in energy by ~3.7 kcal/mol, which means it is thermodynamically more stable. So overtime it is expected that the equilibirum of the cope-rearrangement will lie towards the formation of 10. It is observed that the six membered ring within this molecule can adopt different types of conformers, one of which is twistboat where the energies calculated are shown in table 4. In general chair conformer is the most stable form for six membered ring structures which is what can be seen when comparing 9 chair conformer to 9 twistboat conformer and 10 chair conformer to 10 twistboat conformer respectively, the energies for chair conformers are clearly lower. However the trend remains the same for twistboat conformers, 10 is still observed to be lower in energy than 9. In addition, the energies between chair and twistboat conformations are fairly large, indicating that in order to interconvert between each other, a fair degree of energy is required. Hence it is difficult to simply twist the six membered ring within the polycyclic molecule, which may explain why atropisomers are observed.

| (9)

(kcal/mol) |

(10)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final energy | 63.9718 | 61.2137 | 2.7587 |

| (9a)

(kcal/mol) |

(10a)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final energy | 67.7786 | 66.3293 | 1.4493 |

The energy minimisations of energies of each atropisomers and corresponding conformers can be calculated in a more sophisticated MMFF94 forcefield, the results are shown above in table 4 and 6. Since the method is completely different in considering different interactions; although the outcome energies are different, it can still be observed that the difference in energies between atropisomers are very similar to the ones calculated by MM2 forcefield. Furthermore molecule 10 which has the carbonyl group pointing down is also similarly found to be the more thermodynamically stable than 9.

| hydrogenated(9)

(kcal/mol) |

hydrogenated(10)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM2 energy | 52.6179 | 50.2553 | 2.3626 |

| MMFF94 energy | 75.9569 | 72.7769 | 3.1800 |

On the other hand,literature proposed the existence of hyperstable olefins, which concerns the stability of bridgehead olefins like the norbornene rings in 9 and 10. It is reported that such olefins are very stable, unlike normal olefins. The reasons are not due to steric hindrance or any enhanced pi-bonding, but they contain less strain than its hydrogenated hydrocarbon analogue, hence should be very unreactive as the saturated product is thermodynamically unfavourable.2

Table 7 above shows the energies calculated with the same method MM2 and MMFF94 of the saturated analogues of 9 and 10. In comparison to table 3 and 4, it is clear that the saturated compounds have higher energies roughly 10 kcal/mol more for both types of calculation. This enhances the evidence of these compounds possessing extra stability known as hyperstable olefins.

1. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

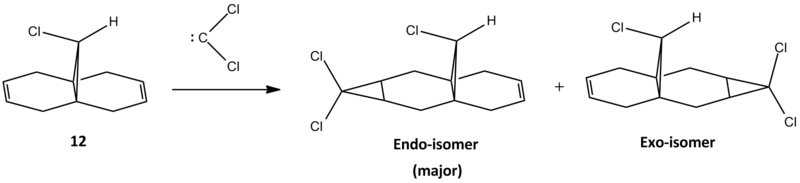

Part.3 - Semi-empirical molecular theory of regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene to a diene

Literature report has shown that onely one mono adduct is found via the reaction of dichlorocarbene and the diene 12, as shown in scheme 5. The carbene attacks selectively from the bottom (endo) face of the ring that is less sterically hindered. In this section semi-empirical molecular theory is used to show the electronic effects that controls the regioselectivity of the addition reaction. The molecule 12 was first minimised using MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 and then compared.

| Iteration of energy | 12(MM2)

(kcal/mol) |

12(MOPAC/PM6)

Heat of formation (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 0.6192 | |

| Bend | 4.7346 | |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.0400 | |

| Torsion | 7.6619 | |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.0657 | |

| 1,4 VdW | 5.7922 | |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1124 | |

| Total Energy | 17.8945 | 19.73995 |

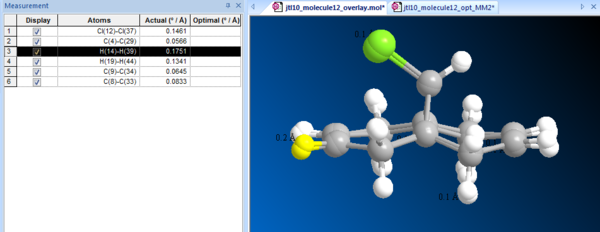

Table 8 shows the summarised energies of molecule 12, the limitation of MM2 can be seen as the energy is different from the one computed by MOPAC. In order to visualise the difference of minimisations, one can measure the deviation by overlaying both optimised molecules as shown in Fig.1. It also shows a list of selected pairs of atoms that differ. The highlighted H atom attached to the olefinic carbon appears to deviate the most from the two models about 0.18 Å, where the MOPAC modelled molecule show greater ring distortion away from the chlorine, which MM2 forcefield was not sophisticated enough to do so.

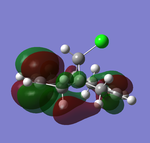

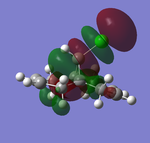

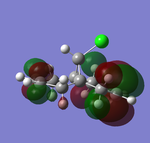

The MOPAC/PM6 modelled molecule was then used further to calculate the energy levels and molecular orbitals. The process was performed under HPC with DFT-B3LYP basis set. 1

| HOMO-1 (47) | HOMO (48) | LUMO(49) | LUMO+1(50) | LUMO+2(51) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visualisation |  |

|

|

|

|

| Energy/a.u. | -0.24519 | -0.23588 | 0.01555 | 0.02025 | 0.03613 |

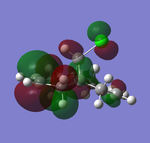

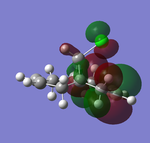

Table 9 above illustrated the computed molecular orbitals of molecule 12 by Gaussian. In general going across the table, increasing number of nodal planes is observed, leading to less bonding characters with increasing anti-bonding character. HOMO-1 shows π-bonding orbitals around both olefins where the electron density is more concentrated on the side that is exo to C-Cl bond. The key HOMO orbital on the other hand shows greater electron density around the olefin endo to the C-Cl bond, where it is more electron-rich and nucleophilic than the exo-olefin, and explains why addition of carbenes are regioselective to the endo-olefin. The π-orbitals are also observed to be large and diffused which allows electrophiles to attack more easily.

The LUMO indicates large anti-bonding on the exo-olefin, the tabulated energies also went from negative to positive by a gap of 0.25143 a.u., suggesting the significant increase in anti-bonding character. At the LUMO+1, the antibonding orbital of C-Cl bond is observed, the density is largely diffused across the bridge. Finally LUMO+2 shows that endo-olefin experiencing large anti-bonding interactions.

Vibrational frequency analysis has been carried out on HPC using b3lyp/6-31G(d,p) basis set.2

| Type | Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity/10-40esu2cm2 | Animation |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-Cl stretch | 771 | 25.1 |  |

| Exo-C=C stretch | 1737 | 4.2 |  |

| Endo C=C stretch | 1757 | 3.9 |  |

The key IR stretches are shown in table 10. The C-Cl stretch is found at 771 cm-1 at lower energy due to the heavier element of Cl atom. The endo C=C is found to be stretching at higher energy than exo C=C by about 20 wavenumbers. This explains the greater electron density around the endo-C=C that makes it more prone to electrophilic attack. The frequencies of these are very low but the reason is unknown and may not play a significant role in the analysis.

1. DOI:10042/22219

2. DOI:10042/22218

Part.4 - Monosaccharide chemistry and the mechanism of glycosidation

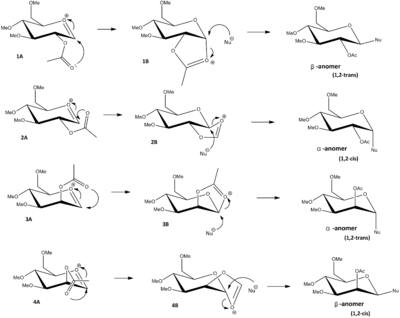

Monosaccharides can undergo glycosidation reactions forming a glycosidic bond a new group often nucleophiles, at the 2-position. The nucleophilic attack can be proceeded at the top or bottom face of the monosaccharide ring, resulting in α- and β-anomers, i.e. substituent at axial and equatorial position respectively. In sugar chemistry, neighbouring group effect is observed to lock either one of the positions by formation of cationic intermediates with presence of acetyl group next to the reacting carbon, in order to selectively produce α- or β-anomer. This excercise involves the investigation of preference in glycosidation of basic monosaccharide stereo/conformational-isomers around the oxonium cation shown in scheme x. The relative energies are established using MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 calculations.

| Iteration of energy | (1A)

(kcal/mol) |

(2A)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

(3A)

(kcal/mol) |

(4A)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.5152 | 2.5227 | -0.0075 | 2.8678 | 2.4463 | 0.4215 |

| Bend | 10.8567 | 13.8653 | -3.0086 | 10.9740 | 12.7151 | -1.7177 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.9797 | 1.0403 | -0.0606 | 1.0855 | 1.0221 | 0.0634 |

| Torsion | 1.0534 | 1.6234 | -0.5700 | 0.9420 | 1.1296 | -0.1876 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.1981 | -1.0688 | -1.1293 | 0.4436 | -4.0025 | 4.4461 |

| 1,4 VdW | 17.9266 | 18.5761 | -0.6495 | 17.9626 | 18.4825 | -0.5199 |

| Charge/Dipole | 4.4460 | 3.4034 | 1.0426 | -13.4956 | 10.6175 | -24.1131 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 4.5033 | 5.9920 | -1.4887 | 7.0173 | 5.6166 | 1.4007 |

| Total Energy | 40.0282 | 44.8251 | -4.7969 | 27.7971 | 48.0273 | -20.2302 |

| Iteration of energy | (1A)

(kcal/mol) |

(2A)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

(3A)

(kcal/mol) |

(4A)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat of formation | -86.77411 | -75.88819 | -10.88592 | -90.51213 | -64.33376 | -26.17837 |

1A and 2A are the conformers of the monosaccharide that has the acetyl group attached to the equatorial position, where the carbonyl group is pointing towards and away from the ring respectively. 3A and 4A are the conformers in similar manner but has the acetyl group attached to the axial position. From table 11 above 1A and 3A clearly show a lower energy than their corresponding conformers 2A and 4A. This can be explained that the carbonyl group is orientated towards the ring and thereby more easily stabilised by the orbital interactions with cationic oxonium ion.

The heat of formations calculated by MOPAC/PM6 of 1A-4A show essentially the same trend as MM2, where 1A and 3A are lower in energy due to the closer orientation of carbonyl towards the ring.

| 1A | 2A | 3A | 4A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| distance/ Å | 1.6 | 4.3 | 1.5 | 4.3 |

| angle/ o | 104 | 132 | 106 | 103 |

Table 13 above shows the distances between the carbonyl and the anomeric carbon, as well as the angle that it tends to attack, the measurements are taken using the MOPAC/PM6 optimised molecules. The low enregy isomers 1A and 3A are orientated at a short distance and close to the famous Burgi-Dunitz angle (~107o), where it is the optimised angle that a nucleophile can approach via collision to an unsaturated site. In contrast 2A and 4A are orientated at a large distance and less ideal angle of attack, therefore it is expected that the intermediates that form from 1A and 3A on the next step are more favourable. However to examine this further, minimised energies of the anomeric carbon-protected oxonium intermediates (denoted as molecule B) are computed below.

| Iteration of energy | (1B)

(kcal/mol) |

(2B)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

(3B)

(kcal/mol) |

(4B)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.0141 | 2.7321 | -0.7180 | 1.7542 | 2.6967 | -0.9426 |

| Bend | 13.5293 | 20.0995 | -6.5702 | 14.1880 | 16.7991 | -2.6111 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.6974 | 0.7782 | -0.0808 | 0.5800 | 0.7679 | -0.1879 |

| Torsion | 7.5269 | 6.0382 | 1.4887 | 7.1019 | 7.7084 | -0.6065 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.5040 | -3.5084 | 1.0044 | -5.2831 | -2.6714 | -2.6117 |

| 1,4 VdW | 17.7906 | 18.3510 | -0.5604 | 18.3936 | 19.4355 | -1.0419 |

| Charge/Dipole | -10.2339 | 3.6952 | -13.9291 | 0.6894 | 0.0312 | 0.6582 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.0051 | -0.1196 | -0.8855 | -0.4246 | -0.7526 | 0.328 |

| Total Energy | 27.8153 | 48.0662 | -20.2509 | 36.9995 | 44.0148 | -7.0153 |

| Iteration of energy | (1B)

(kcal/mol) |

(2B)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

(3B)

(kcal/mol) |

(4B)

(kcal/mol) |

Energy difference

(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat of formation | -91.64229 | -66.72495 | -24.91734 | -91.66024 | -66.64493 | -25.01531 |

As expected from previous section, both MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 show that 1B and 3B possess lower energy than their conformers. It can be observed that energies of 1B and 3B as well as 2B and 4B greatly resembles to each other respectively, this is because in fact their intermediates are very similar in structure, such that the final product that the similar pairs of molecules form will also be close in energy and stability.

With 2B and 4B at higher energies, this suggests that neighbouring group effect is not favourable on the alternative face of the monosaccharide ring where its reactants (2A and 4A) are higher in energy. In conclusion this explains the fact that 1,2-trans product is highly favoured in glycosidation reactions when neighbouring group effect is also favoured to occur. 1-2,cis is not the product that neighbouring group effect would lead to, due to both intermediates are higher in energy that rules out the possibility of them forming.

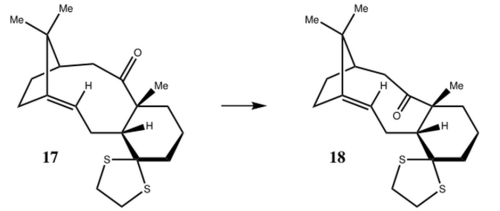

Week 2 Mini Project - Simulation of spectroscopic data for a literature molecule

| Calculated Shift (ppm) | Literature Shift (ppm) | Degeneracy | Atoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.07 | 5.21 | 1 | 26 |

| 3.24 | 3.00-2.70 | 2 | 50,48 |

| 3.12 | 3.00-2.70 | 1 | 49 |

| 3.02 | 3.00-2.70 | 1 | 47 |

| 2.89 | 3.00-2.70 | 1 | 32 |

| 2.83 | 3.00-2.70 | 1 | 27 |

| 2.72 | 2.70-2.35 | 1 | 33 |

| 2.66 | 2.70-2.35 | 1 | 24 |

| 2.51 | 2.70-2.35; 2.20-1.70 | 3 | 30,41,34 |

| 2.23 | 2.20-1.70 | 2 | 53,43 |

| 2.06 | 2.20-1.70 | 3 | 25,31,42 |

| 1.90 | 1.58 | 1 | 29 |

| 1.61 | 1.50-1.20; 1.10 | 4 | 28,45,37,40 |

| 1.36 | 1.10 | 2 | 52,44 |

| 1.28 | 1.07 | 2 | 46,36 |

| 1.05 | 1.07; 1.03 | 2 | 35,38 |

| 0.97 | 1.03 | 1 | 39 |

| 0.70 | 1.03 | 1 | 51 |

18nmr |

| Shift (ppm) | Literature Shift | Degeneracy | Atoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| 214.25 | 211.49 | 1 | 13 |

| 150.21 | 148.72 | 1 | 2 |

| 121.74 | 120.90 | 1 | 3 |

| 91.66 | 74.61 | 1 | 14 |

| 59.35 | 60.53 | 1 | 9 |

| 54.78 | 51.30 | 1 | 12 |

| 54.52 | 50.94 | 1 | 6 |

| 50.10 | 45.53 | 1 | 7 |

| 49.02 | 43.28 | 1 | 15 |

| 46.75 | 40.82 | 1 | 20 |

| 41.72 | 38.73 | 1 | 19 |

| 41.40 | 36.78 | 1 | 17 |

| 39.38 | 35.47 | 1 | 4 |

| 34.41 | 30.84 | 1 | 8 |

| 34.21 | 30.00 | 1 | 23 |

| 28.51 | 25.56 | 1 | 1 |

| 26.84 | 25.35 | 1 | 11 |

| 24.71 | 22.21 | 1 | 5 |

| 23.27 | 21.39 | 1 | 10 |

| 22.37 | 19.83 | 1 | 16 |

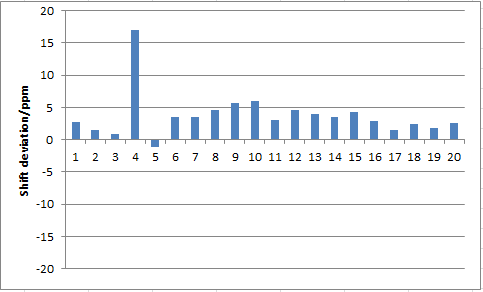

From table 17 and fig 0, the computed NMR data of molecule 18 is very similar to the literature report. 1The deviations of chemical shift are mostly within about ± 5 ppm except an anomaly of carbon 14, the reason that caused this large error is unknown it could either be a single calculation mistake of NMR, or possibly the experimental value of the literature report recorded wrongly. H NMR is also compared and tabulated in table 16. Although most values fall into the range that the literature state, it cannot be compared appropriately, as the uncertainties are too large; there are also some overlappings between peaks that happen to be in degeneracy. It is also worth to mention that the literature C and H NMR data are ran under C6D6, which is not the same as common CDCl3. The calculations are done under chloroform and referenced against chloroform, this could induce the small errors in shifts. Since the carbon-13 NMR shifts are at scale of 20 up too more than 200 ppm, the relative percentage error appears to be less with reasonable tolerance of ± 5 ppm, however for H NMR the peaks are found within 0-10 ppm, the relative error can significantly affect the assignment of peaks.

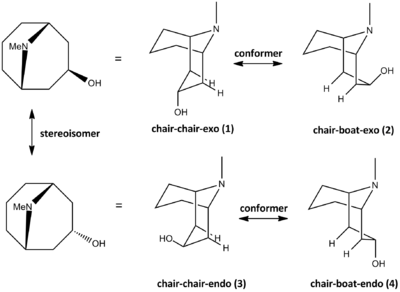

Part.2 - Literature molecule - 9-Azabicyclo[3.3.l]nonane Derivatives - granatanol

Introduction and Minimisation

Bicyclic molecules often exist as different conformers due to the flexible interconversion between chair and boat structure in a six-membered ring. However sometimes the conversion can be limited due to bulky substituents; there can also be stereoisomers if a chiral centre is present. Granatanol consists of a bicyclic piperidine ring bridged by an amine group; the hydroxyl group is stereoisomeric where it can point up(exo) or down(endo) with respect to the longest bridge. Each of the stereoisomers can give two possible conformers as double chair or chair-boat. These are illustrated in scheme 8.17

All four isomeric and conformational structures are constructed using Chembio 3D and minimised with MM2 forcefield. The energies are shown below in table 18.

| chair-chair-exo-(1)

(kcal/mol)1 |

chair-boat-exo-(2)

(kcal/mol)2 |

chair-chair-endo-(3)

(kcal/mol)3 |

chair-boat-endo-(4)

(kcal/mol)4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total energy | 25.3595 | 25.0699 | 28.1334 | 27.1850 |

| (1)

(kcal/mol) |

(2)

(kcal/mol) |

(3)

(kcal/mol) |

(4)

(kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat of formation | -65.56236 | -68.08572 | -64.61164 | -64.77556 |

From the MM2 results for either endo and exo isomers, it is found that the chair-boat conformation has a lower energy which is thermodynamically more stable. This is consistent with the literature, as it quoted that "the isomer exists predominately in the chair-boat conformation in order to relieve the transannular steric interaction in the chair-chair conformation." It is most obvious when we observe endo chair-chair conformed molecule 3 has the highest energy out of all, where the OH group is potentially having steric hindrance with the hydrogens attached to the carbons in the upper ring. For the exo-isomer the energies are very close as in terms of sterics the OH groups for both conformers are not sterically clashing into any possible atoms; but chair-boat conformer is still obtained to be the slightly more stable one. The heat of formations of these four molecules are also obtained by calculation using MOPAC/PM6, although the difference in energy appears to be small, the general trend of chair-boat conformation are still observed to be more thermodynamically stable. It is interesting that MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 results show the same trend that overall the exo-isomers are slightly more stable than the endo-isomer, which is not mentioned in the literature.17

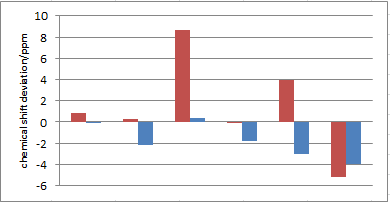

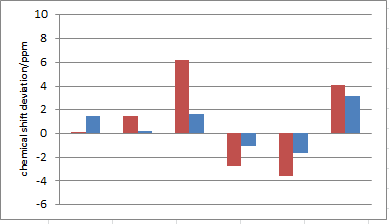

In order to distinguish between the isomers or conformers experimentally, one would usually obtain the analysis of 1H, 13NMR or X-ray crystallography to define the plausible position of the atoms hence its structure. For H NMR it is useful to define conformers by analysing the chemical shifts of hygrogens that can flip between chair-chair and chair boat; as the hydrogens in chair boat conformation are nearer to the nitrogen. C NMR is also useful to distinguish between exo and endo, as shown in the literature report. The following section examines the NMR data calculated by HPC and is compared to the literature report.17

13C NMR

This section includes the calculated NMR data of DFT-mpw1pw91-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) optimised 1-4. The solvent used is assumed to be CDCl3 hence the data exported is referenced to TMS mpw1pw91-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)CDCl3.

| Calculated Shift (ppm)5 1 chair-chair exo | Calculated (ppm)6 2 chair-boat exo | Literature Shift (ppm)17 | Degeneracy | Atoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65.21 | 64.30 | 64.4 | 1 | 9 |

| 54.17 | 51.73 | 53.9 | 2 | 4,6 |

| 43.98 | 35.67 | 35.3 | 2 | 7,8 |

| 40.38 | 38.75 | 40.5 | 1 | 11 |

| 23.76 | 16.74 | 19.8 | 1 | 2 |

| 22.21 | 23.47 | 27.4 | 2 | 3,1 |

| Calculated Shift (ppm)7 3 chair-chair endo | Calculated (ppm)8 4 chair-boat endo | Literature Shift (ppm)17 | Degeneracy | Atoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62.16 | 63.46 | 62.0 | 1 | 9 |

| 52.38 | 52.29,52.01 | 51.9 | (2) | 6,4 |

| 41.61,40.56 | 37.93,35.20 | 34.9 | (2) | 8,7 |

| 37.63 | 39.35 | 40.4 | 1 | 11 |

| 21.53,21.48 | 23.50,23.45 | 25.1 | (2) | 3,1 |

| 18.60 | 17.17 | 14.5 | 1 | 2 |

Both conformers of the isomers are compared to literature, from tables above and figures on the right the chair-boat conformer of both exo and endo isomers seem to produce less deviation from the literature values (all within ±5 ppm), whereas some data of the chair-chair conformers show very large deviation especially carbon 7 and 8. This suggested the computed molecule for exo and endo isomer of granatanol both tend to exist as chair-boat conformer, again it is consistent with the MM2 minimisation and also what the literature report has described.

IR vibrational spectrum

The IR vibrational spectra of each isomer/conformers can be predicted by DFT-b3lyp/6-31G(d,p)frequency analysis.

| Mode # | Type | Chair-chair exo 1 Frequency/cm-19 | Intensity/10-40esu2cm2 | Animation | Mode # | Chair-boat exo 2 Frequency/cm-110 | Intensity/10-40esu2cm2 | Animation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | O-H wagging | 355 | 83.2 |  |

not found | - | - | - |

| 78 | O-H stretch | 3789 | 6.6 |  |

78 | 3648 | 127.4 |  |

| 36 | C-N stretch | 1177 | 11.5 |  |

36 | 1177 | 24.0 |  |

| 67 | C-H stretch | 3042 | 115.9 |  |

74 | 3083 | 96.9 |  |

| Mode # | Type | Chair-chair endo 3 Frequency/cm-111 | Intensity/10-40esu2cm2 | Animation | Mode # | Chair-boat endo 4 Frequency/cm-112 | Intensity/10-40esu2cm2 | Animation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | O-H wagging | 308 | 114.7 |  |

8 | 318 | 17.7 |  |

| 78 | O-H stretch | 3808 | 10.1 |  |

78 | 3809 | 9.1 |  |

| 36 | C-N stretch | 1174 | 18.6 |  |

36 | 1180 | 25.8 |  |

| 69 | C-H stretch | 3049 | 92.3 |  |

74 | 3080 | 70.9 |  |

Above tables have shown the calculated vibrational modes of each molecule 1-4. Gaussview was used to generate the figures and animations. Key vibrational modes that can identify the molecule are chosen to record in the table. The main functional groups present in granatanol are tertiary amine and primary alcohol. The OH stretch of all 4 molecules are found in the range of 3600-3800cm-1, the intensities are small except for chair boat exo molecule 2, of which the reason is unknown. OH peaks are often broad and the exact range of wavenumbers are difficult to predict. The other key vibrational mode is C-N stretch, which is found in all 4 molecule at ~1180cm-1, the intensities are quite low and this is expected, since tertiary C-N peaks are often overlapped and hard to observe. The O-H wagging was also picked due to the chair-chair isomers showing large intensities in this peak, however it is unknown why the OH wagging is not identified for conformer 2. There are too many different types of C-H stretch, where it is impossible to assign all individually. For each molecule the C-H stretch with highest intensities are picked as an example, they all fall typically into the range for C-H which is ~3000cm-1. From the animations these happen to be similar in representing small stretches of almost every C-H bonds within the molecule.

| (1)

(kcal/mol) |

(2)

(kcal/mol) |

(3)

(kcal/mol) |

(4)

(kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total energy | -303028.37 | -303029.15 | -303025.46 | -303026.50 |

| (1)

(kcal/mol) |

(2)

(kcal/mol) |

(3)

(kcal/mol) |

(4)

(kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entropy change | 1016.65 | 1016.65 | 1016.65 | 1016.65 |

Table 24 shows the total free energy of the conformers and isomers, similar to the energy minimisation again the chair-boat conformers are slightly more thermodynamically favourable than chair-chair conformer. It can also be seen that the exo-isomers are lower in energy than endo isomers, which is also consistent with the result obtained by MM2 and MOPAC/PM6. The values of free energies are largely negative, indicating the formation of them are highly favourable. In combination with the heat of formation calculated from previous section, in effect entropy can be obtained by using ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, where the values calculated using room temperature 298K are tabulated above. Since the free energy as well as heat of formation differences are very small, the changes in entropy of all isomers/conformers turn out to be the same (to 2 d.p.). The values are largely positive indicating the property of highly thermodynamically favourable.

Optical Rotation

| (1)13

(deg) |

(2)14

(deg) |

(3)15

(deg) |

(4)16

(deg) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical rotation | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.58 | 30.47 | ||||||||||||

| 'Molecule visualisation |

|

|

|

|

The optical rotation of 1-4 were computed using CAM-b3lyp/ 6-311G(d,p) basis set and chloroform as solvent with the DFT-mpw1pw91-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) pre-optimised molecules. Both conformers of the exo-isomers turned out to have zero degree of optical rotation, this could be due to the high level of symmetry within the molecule, and in fact a plane of symmetry can be observed in the jmol files of 1 and 2. The optimised molecules of 3 and 4 somehow happen to have the O-H bond twisted creating an angle that destroys the symmetry, hence optical rotation is observed. There is no approproiate comparisons to be made between conformers and isomers 1-4 because none of them are enantiomeric to each other, which means it has no mirror image to possess exact opposite optical rotation. However it can be established that a small degree of twist in OH bond can affect the value of optical rotation, as the twisted OH of 3 and 4 is not significant but almost a doubled value is recorded.

1. DOI:10042/21636

2. DOI:10042/21641

3. DOI:10042/21640

4. DOI:10042/21639

5. DOI:10042/21637

6. DOI:10042/21633

7. DOI:10042/21634

8. DOI:10042/21632

9. DOI:10042/21631

10. DOI:10042/21629

11. DOI:10042/21630

12. DOI:10042/21628

13. DOI:10042/21627

14. DOI:10042/21626

15. DOI:10042/21624

16. DOI:10042/21623