Rep:Mod:ja2209module1

Joshua Almond-Thynne: Year 3 Computational Labs - Module 1: Symmetry and Spectroscopy

Introduction

Computational chemistry is a branch of chemistry that allows the calculations of molecules that may be hard to make/isolate/handle to form relatively accurate ideas of reactivity and physical properties. It can also be used to solve puzzles of selectivity or lack of selectivity in certain reactions. In this module two types of comutational methods are going to be used to study a few prime examples of where computational chemistry can explain certain outcomes of reactions. The first was molecular mechanics based methods (mainly MM2) that used Newtonian physics at its core to minimize a compounds energy. The first of these methods started appearing in the late 1940's-early 1950's but was truly pioneered by Norman Allinger who wrote the Force field methods MM2/3/4 based on molecular mechanics. The second is the semi-empirical method based on the Hartree-Fock formalism. In this investigation MOPAC in particular was used which was largely written by the group of Michael Dewar[1] at the University of Texas, Austin.

Unless stated otherwise all models were draw in ChemBio 3D 12.0 with MM2 calculations being run at a Minimum RMS gradient of 0.010. With PM6/AM1 calculations also being run in ChemBio through the MOPAC interface with a Closed Shell Wavefunction (UHF) and an EF Optizimer. Later in the project for vibrational analysis and NMR prediction the calculations were run through Imperial College London's SCAN network through Gaussian 09W and exported into animations/displays/spectra through Gaussview 5.0. All pictures of compounds mentioned have been draw in ChemDraw Pro and exported as .gif

Modelling and Molecular Mechanics

Introduction

Molecular Mechanics focuses on Newtonian physics to model molecular systems. The total energy of the system is equal to the total of the covalent/bonded interactions between molecules of and the the interactions between the non-bonded atoms.

The sum of the energy between each bonded atom is dependent on bond energyies, angles and the dihedral angles. The non-bonded energies are reliant on electrostatic repulsions and Van-Der Waals interactions.[2]

Ebonded = Ebond+ Eangle+ Etorsion

Enon-bonded = Eelectro +Evdw

| Factor | Equation | Definition of All Terms | Comparative Classical Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond | Ebond = Σ E Sbond=Σ kij(rijk-rijk0)2 | kij=Bond Force Constant, rijk=Bond length, rijk0 = Equilibrium bond length | Hooke's Law |

| Angle | Eangle = Σ E Sangle=Σkijka(θijk-θijk0)2 | kijk=Bond Force Constant, θijk=Bond angle,θijk0 = Equilibrium bond angle | N/A |

| Torsion | Etorsion = Σ E Storsion=Σ kijklt(1+cos(nαijkl- αijkl0)) | kijkl=Bond Force Constant, αijkl=Torsion angle,αijk0= Equilibrium Torsion angle | N/A |

| Electrostatic Replusion | Eelectro = Σ E Selectro=Σ ( qiqj)/(eijrij) | eij is a constant, qiqjare charges of atoms,

rijis the distance between atoms. |

Coulomb's law |

| Van-Der Waals | Evdw = Σ E Svdw= Σεij ((σij/rij)12 - 2(σij/rij)6) | rijdistance between atoms,σijdistance at Van der Waals energy is minimum | Lennard-Jones potential |

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene “Cp” is a extremely important ligand in Inorganic complexes, especially in the field of catalysis due to the fact it can easily ring slip for a η5 to η3 to η1 thus allowing the metal centre to have a varying number of ligands during a multi-stage catalytic cycle. A large industrial application of Cp-containing complexes is the Ziegler–Natta catalysts which are used in the synthesis of terminal alkene based polymers[3]. Cyclopentadiene at room temperature exists as a dimer. This is due to the high thermal stability of the dimer comparatively to the monomer and the ease at which it can dimerise via a [2πs+4πs] cycloaddition Diels-Alder Reaction.

In this particular modelling exercise computational chemistry can show which isomer of the dimer is most stable and whether the mechanism follows a thermodynamic pathway or a kinetic pathway and the stablity of the hydrogenation product of the major dimer showing which would be the major product in the hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene.

Diels Alder Reactions

Diels Alder Reactions is generally considered the "Mona Lisa" of reactions due to the small emergy needed to create a substituted cyclohexene system from a reaction between a conjugated diene and substituted alkene[4] . Many cases show the favourability of the formation of the endo product over the exo[5]. The difference between the endo and exo products form when the diene and the dienophile approach. To form the exo product the dienophile approaches from the above whereas in the endo it approaches from the bottom. From the table below it can be seen that the endo product has a higher energy (+2.12 kcal/mol) than the exo product. As this is the major product it is shown that the reaction is under kinetic control. This implies that the endo product has a lower energy transition state. The reason for the increased energy of the endo product is mostly caused by the torsion in the endo being higher due to the two alkene bonds being closer together which is unfavourable (alkene to alkene distance difference ~3Å).

A reaction pathway can be seen with a quantitative analysis of the endo transition state showing that there are additional stabilizing interactions in the approach from above/behind of the diene between its high energy HOMO and the dienophiles low lying LUMO. This evidence would strengthen the argument for the endo product being favorable, however it may not be completely impossible to make the thermodynamic product. The issue in forming the exo product would be that nearly all pericyclic reactions form substantially more stable products and therefore are rarely reversible reactions[6], particularly in this case as the reaction occurs readily at room temperature. However, if there is a chance that the endo product can slip back to the reactants the exo product predominates[6]

The Hydrogenation of the Endo Product

From the modelling and calculations from section 1.2.1 above it is fair to assume that the first step in the hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene is under kinetic control rather than thermodynamic showing the endo product will be hydrogenated. In the next set of calculations MM2 force field optimization is used to see which of the two alkene bonds present in the dimer when hydrogenated give a more stable prouduct. Products 3 and 4 were optimized and the data is tabulated in table 2. As you can see the product 4 is the lower of the two with a difference of 4.533kcal/mol in is majority caused by the large difference in bend energies (difference= 5.34kcal/mol), This is due to the face is you look at the angle in the remaining alkene bond there are very different. In the favoured product 4 the alkene bond angle is (112°) and in product 3 it is (108°). In the lowest energy state a sp2 carbon in the alkenes will have a bond angle of 120 but deviation from this minima causes strain and an increase in energy showing that product 3 is disfavoured.

| Modelling Data | HYdrogenation Reaction Scheme | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From this modelling it can be concluded if the hydrogentation of the endo isomer was under thermodynamic control it can be said the major product will be product 4. However this may not be the case as hydrogentation as well as diels-alder could follow a kinetic pathway however in this particular example no obvious quantitative assumptions can be made about transtition states between product 2 and 3/4 therefore at this level of modelling it can be assumed that product 4 in the major product.

Stereo Chemistry of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Taxol is the trademark name for the drug Paclitaxel. Discovered in 1967 at the U.S. National Cancer Institute by Monroe E. Wall and Mansukh C. Wani by isolating it from the bark of the Pacific Yew tree. Its primary application is in the treatment of lung, ovarian and breast cancer. With other application is the treatment of of extreme forms of Kaposi's Sarcoma

Modelling the Intermediates

A key intermediate in the total synthesis during the first thermally-induced retro-oxy-cop rearrangement[7] shows isomerisation were one product is found to form quickly but slowly inter-converts back to the other[7] therefore implying the reaction have competing kinetic and thermodynamic products[6], The differences in the two intermediates is the orientation of the carbonyl. In intermediate 9 the carbonyl is facing up along with the bridge-end carbons, in intermediate 10 the carbonyl faces down from the ring away from the bridge-end carbons. At a first glance it can be assumed that Intermediate 10 would be favorable due to the steric classing between the bulky methyl groups of the bridge-end and the electron rich carbonyl however to conclude this MM2 modelling was used on both intermediates to find the key differences.

Table 3 has the tabulated MM2 force field calculations and major differences in the carbonyl carbon bond angles. This sp2 optimally should have a 120° bond angle. In the preferred intermediate 10 the bond angle around that carbon center is 119.8° when in intermediate 9 it is 125.4°. Using the idea as in the hydrogenated products of cyclopentadiene dimer a angle further from the optimal has a higher bend energy therefore 10 is preferred over 9.

| Modelling Data | The Two Taxol Intermidiates Under Investigation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However something else came up from the calculations, there are multiple isomers of both the intermediates with different cyclohexane ring conforms, however these all have very high energy and that is why they are not observed at all. Therefore I focused on the two under investigation

In conclusion it can be seen that intermediate 9 is the kinetic product and can be promoted by low heat and quick reaction times and intermediate 10 is the thermodynamically favorable product and is promoted by high heat and long reaction times.

Hyperstable Alkenes

In the original literature it is noted that both of these intermediates react abnormally slow[7]. This is due to an alkene to a bridgend carbon forms a "Hyperstable Alkene"[8] has less steric strain to its analgous hydrogenated product. I.E. The bond angle of the alkene at the bridge-end end is closer to its optimal angle comparatively to the alkane. An example of this can be seen in the table below with Intermiediate 10 comparing its hydrogenated partner including bond angles around the carbon in question and the discrepancy from the optimal.

| Modelling Data | The Two Taxol Intermidiates Under Investigation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In a case like this is it possible to calculate the Olefin Strain which is equal to the difference in the torsion energies of the alkene and alkane analogous compounds[8].

Torsion (C=C) - Torsion (C-C) = 18.2949-23.0714 = -4.7765 kcal/mol

By definition a Hyperstable Alkene is an alkene with negative olefin strain[8], In this case it can be seen Taxol intermediate 10 exhibits this characteristic and this is the explanation for the abnormally slow reactivity.

Modelling Using Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Theory is based on quantum chemistry which focuses on the energy of electrons and wavefunctions rather than the bonds within the compounds. Within the framework some pieces of information is approximated to cut down on excessively long computing times. For π-electron systems a form of Hückel Method introduced by Erich Hückel[9] and for valence electron systems energies are calculated by the Extended Hückel method introduced by Roald Hoffmann[10]. Nearly all methods (including MOPAC) are based around the Hartree–Fock algorithm which solves the time-independent Schrödinger equation for multi-electron systems. The problem is solved numerically due to there is non-know many electron systems. Each equation is solved using a non-linear method such as a iteration which gave rise to its other name "self-consistent field method".

Approximations involved are:

- The Born–Oppenheimer approximation is assumed.

- Relativistic effects are completely neglected.

- The variational solution is assumed to be a linear combination of a finite number of basis sets.

- Each energy eigenfunction is assumed to be dependany on a single Slater determinant.

- Electron Correlations are completely neglected for the electron with opposite spin but are taken into account for those with parallel spin.

A flow diagram of the algorithm can be seen to the right.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

|

The addition to the electrophilic regents such as dichlorocarbene to compound 12 (9-Chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,8a-methanonaphthalene) regioselectivty attack the endo alkene facing away from the Cl on the bridge-end carbon[11]. This implies a difference in energy between the endo and the exo. In this investigation modelling of the molecular orbitals of compound 12 will be made and they will be used to find the reasoning behind this selectivity.

Molecular Orbital Modelling

The first thing to be mentioned is during the calculated of molecular orbitals there is a flaw with the PM6 method. Compound 12 has a plane of symmetry intersecting the two alkene bonds. For unknown reasons there is a bug in the PM6 method for molecular modelling causing inaccuracy in molecules with symmetry within them. You can see this is the provided PM6 calculated MO's below and the fact they are not symmetrical which they obviously should be. Therefore a different parameter set was used within Guassview after stating the compound had Cs after forced symmetrization. This allowed Gaussian to calculate half of the MO and then reflect to cover the other side of the molecule giving more accurate and more importantly symmetrical MO's which can also be seen below.

| Frontier Orbitals of Dialkene Compound 12 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOPAC |  |

|

|

|

| Gaussview |   |

|

|

|

Looking at the HOMO which is the most important orbital due to this is the orbital being attacked by the electrophile in this reaction, it lies heavily to the endo explaining why the endo is prefered over the exo in terms of electrophilic attack. To understand why there electron density lies on the endo analysis of the HOMO-1 and LUMO+1 shows there is a overlap between the low lying σ*C-Cl orbital and the high lying exo πC=C orbital. This would lower the energy of the exo C=C bond making it more stable and less prone to nucleophilic attack explaining why electron density lies exclusively on the endo in the HOMO causing the regioselectivity during addition. A energetics diagram (on the right) shows the interaction in a simplified form showing the exo bond has less electron density present and at a lower energy (present in the HOMO-2).

Vibrational Spectra Investigation

To fully understand the πC=C→σ*C-Cl interaction vibrational spectra were estimated using the method:

# b3lyp/6-31G(d,p) opt freq

The main points of interest on the spectra are the two in equivalent alkene stretches at 1737cm-1 and 1757cm-1 showing there is a difference in the energies of the two bonds. The other is the tall sharp peak at 770.91cm-1 representing the C-Cl bond. The two small peaks for C=C bonds are very similar in wavenumber (difference of 20cm-1) however this is what would be exprected for this level of interaction. The higher alkene stretch at 1757cm-1 is the endo C=C bond as it has increased electron density on the bond comparatively to the exo which has part of its electron density located on the σ*C-Cl orbital. The spectra and the bond stretches of interest are tabulated below.

| Vibrational Spectra of Compound 12 |  | ||

| Stretch And Animation | C-Cl @ 770.91cm-1  |

endo C=C @ 1737cm-1 |

exo C-Cl @ 1757cm-1  |

Monoalkene

The same approach was taken with the monoalkene, only leaving the endo present in the molecule, the IR's are similar in each showing the overall interaction does not have a large impact. The important difference is the shift of the C-Cl bond to 774.94cm-1. With a increase of +4.03cm-1 it shows that without the endo alkene the C-Cl becomes stronger due to no interaction with its σ*C-Cl orbital. This difference in energy proves the interaction hypothesized.

| Structure | Vibrational Spectra of Monoalkene |

|---|---|

|

|

Effect of Substituents on Vibrational Spectra

In an additional investigation on the effect of electron density on the alkene the endo alkene affecting the interaction between the σ*C-Cl orbital exo πC=C. To do this two substituted compound 12's were modelled with both electron donating groups (EDG) and electron withdrawing groups (EWG). In this example the the EWG under investigation is the Nitro group (-NO2). One of the most electron withdrawing groups should draw electron density from the endo C=C bond, This is turn should lower the interaction with the σ*C-Cl exo πC=C meaning the C-Cl bond should shift up in wavenumber. (Also less importantly endo C=C bond lowers)

From the IR spectra the C-Cl bond stretch has a value of 776.77cm-1 confirming removal of electron density from the endo bond lowers the interaction which weakens the C-Cl bond .The endo C=C bond stretch has a value of stays the same at 1737cm-1 however in the [animation] the bond stretch has a higher intensity, this retention of energy may be due to conjugation with the nitro groups.

Vice versa in the case of an EDG, in this example amino (-NH2) should have the oppisite effect. And again this is seen with a C-Cl bond stretch frequency at 756.72cm-1 consinderably lower than that of Compound 12's C-Cl stretch. It is also seen that the endo C=C bond stretch increases to 1765.74cm-1 which corresponds to making bond stronger with additional electron density. The structures and spectra are tabulated below.

| Structure | Vibrational Spectra of Monoalkene |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Monosaccharide Chemistry: Glycosidation

Introduction

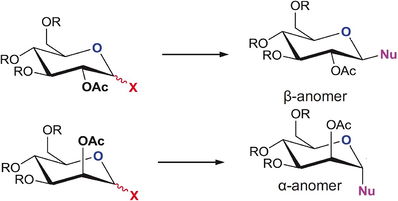

In carbohydrate chemistry an essential reaction is the Fischer Glycosidation[12]. Most commonly is substitution for a -OH group present on the anomeric carbon for a -OR by dissolving the original sugar in the alcohol (ROH) and may be catalysed by an external compound (example Trimethylsilylchloride. This reaction is a famous example of a stereoelectronic effect controlling the stereochemistry of the compound.

In carbohydrates the main stereoelectronic effect occuring is the anomeric effect[13], this makes the major product of glycosidation reactions the α-anomer where the -OR group is axial on the anomeric carbon so the ring oxygen can donate is lone pair into the σ*C-O. This being formal resonance by Hyperconjugation lowers the α-anomer energy meaning it is favoured.

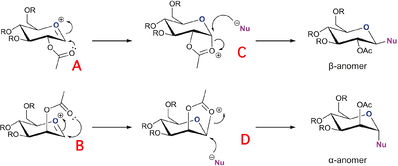

However in this investigation we are looking at a effect not always seen in sugars: neighboring group participation (NGP). With an -OAc adjacent to the anomeric carbon the carbonyl group can stablise the hyperconjugated sugar further controlling the regioselectivity even more[14], In this investigation we will be looking at how this NGP effects the energies of the compound and what will be the major outcome. But also the underlying impact on what parameters you use to model you compound. Namely Molecular mechanics vs. Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Anomer Modelling

Molecules A B C D exist in two forms, each compound have have the carbonyl group above or below the ring, with there corresponding analougous compounds A*, B*, C* and D*. Firstly each compound was minimized with MM2 force field parameter and the data is tabulated below. From there using the MOPAC interface they were subjected to minimization via PM6 parameters with the jmols and heat of formations provided in the table below.

Molecules A-D and A*-D* were modeled with OMe groups. This is because this minimizes calculation time because it is not bulky and has small flexibility. It would minimize steric clashing even more if H was used however this would invoke MOPAC calculating hydrogen bonding effecting results and increasing calculation time. Another reason is that some force field parameters set -Me groups as hard-sphere molecules minimizing calculation time even more.

| Molecule | Carbonyl Posistion | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Charge/Dipole | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy (MM2) | Heat of Formation (PM6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Below The Ring | 2.615 | 12.658 | 1.016 | 2.022 | 0.612 | 19.118 | -31.3710 | 9.3472 | 16.0172 | -91.173 |

|

|

Above The Ring | 2.381 | 10.966 | 0.898 | 2.293 | -2.796 | 19.3476 | -11.399 | 6.868 | 28.558 | -85.045 |

|

|

Above The Ring | 2.204 | 11.856 | 0.798 | 3.0589 | -0.046 | 20.576 | -29.243 | 6.114 | 15.317 | -88.534 |

|

|

Below The Ring | 2.206 | 10.903 | 0.892 | 3.305 | -2.451 | 20.306 | -18.303 | 4.9576 | 21.8163 | -79.383 |

|

|

Below The Ring | 2.089 | 14.152 | 0.7677 | 9.6276 | -2.632 | 17.861 | -8.5274 | -1.976 | 31.3608 | -91.650 |

|

|

Above The Ring | 2.794 | 18.498 | 0.884 | 9.068 | -2.088 | 19.051 | -0.356 | -1.441 | 46.100 | -66.849 |

|

|

Above The Ring | 1.970 | 12.7156 | 0.647 | 7.691 | -2.026 | 18.033 | -13.184 | -1.088 | 24.7572 | -87.730 |

|

|

Below The Ring | 2.572 | 18.616 | 0.672 | 4.6229 | -3.308 | 18.7012 | 2.002 | -1.145 | 42.734 | -66.843 |

The main points of interest from the table are the following:

- A and B are both lower than A* and B* in MM2 due to large difference in MM2 Charge/Dipole interaction. In non-bonded energy the carbonyl oxygen and the oxonium oxygen can be seen as point charges, the closer they are together the more stabilizing the interaction. The distance from the carbonyl oxygen and oxonium is the following:

- A=2.65Å,

- A*=4.08Å,

- B=4.07Å

- B*=4.20Å

- A and B are both lower than A* and B* in PM6 because of a similar interaction, this is more dependent on the distance between the carbonyl oxygen and the anomeric carbon where a nucleophilc attack like resonance seen in NGP can occur (if carbonyl is at Bürgi–Dunitz angle 109.5°) again the closer these atoms are the larger the interaction and closer to the Bürgi–Dunitz angle. The distance (D) and angle (θ) from the carbonyl oxygen to the anomeric carbon is the following:

- A(D=1.59Å θ=105.1°)

- A*(D=4.20Å θ=131.4°)

- B(D=1.61Å θ=105.7°)

- B*(D=3.81Å θ=150.4°)

- The next point of interest is that A in terms of MM2 is less energetically favourable that B this is due to the equatorial position has more steric clashing with the ring than the axial (in B) where there are few equatorial subtituents therefore minimal 1,3 Diaxial Strain. However A is favoured over B in PM6 due to slightly closer carbonly oxygen - anomeric carbon distance and slightly less deviation from the Bürgi–Dunitz angle so there is better overlap.

- Another point which is the explanation to the stereoselectivtiy seen in glycosidation is the fact that C and D and lower in energy (both MM2 and PM6) than C* and D*. This shows why with A and B you get the β and α anomers respectively. This is because the pathway for an equatorial -OAc (A) to come above the ring to form C* which then only allows nucleophilic attack from the bottom face is energetically unfavorable. And this is the same with B/B* and D/D* which is the cause of the selectivity caused by the NGP effect.

- The final point to make is that A=C and B=D in terms of PM6 because using the PM6 method there bond between the carbonyl and anomeric carbon is "made" and contributes to the final energy because it is molecular orbital based therefore drawing the bond in ChemBio has no effect on PM6 because it was already computed. However the MM2 energies will not match due toonly formed bonds being taken into account. This is why you can never compared between different force field parameters.

Mini Project

Aims and Objectives

In this project, the topics that are trying to be covered [15]

- Find a reaction to study that

- Have molecules that are not highly conformationally flexible

- Produce isomeric products

- Include 13C NMR of the isomeric products

- Which through investigation it must be found how to

- Differeniate the isomers spectroscopically

- Calculate the predicted 13C NMR

- Compare the predicted data to the experimental 13C NMR data in the paper

- Finally use all the data to discuss the mechanism of the reaction and why there is or isn't selectivity

An Introductions to Click Chemistry

Click chemistry was first introduced in 2001 by Sharpless at Scripps [16][17]. It is a philosophy for organic synthesis tailored in creating biological like reactions for joining small units together to form one larger product. The general concept is a reaction that mimics nature.

To be a "Click" reaction the reaction must have several qualities:

- Be modular

- Be stereospecfic

- Be wide In scope (work with lots of substituents)

- Provide high chemical yields

- Provide high atomic yield

- Produce easy to remove and non-toxic byproducts

- Have a large thermodynamic driving force

- Be physiologically stable

- Have mild reaction conditions

- Work with widely available starting products

- Preferably have no solvent (water is acceptable)

- Provide products that are easily isolated and purified

An ideal example of this type of chemistry is the Azide Alkyne Huisgen Cycloaddition which was first developed by Rolf Huisgen[18] which can be seen in the figure to the right of the page. It was found in 2002 that this reaction can be accelerated in the presence of a Cu(I) catalyst[19] and giving specific selectivity to the 1,4 isomer when in the presence of a Ru(II) catalyst it gives the 1,5 isomer[20]. In this particular investigation The R-groups R1= -CH2Ph and R2= -Ph.

Initial Calculations

Initial Calcualtion were run on both isomers using both molecular modelling and quantum mechanics based force fields, the date tabulate below contain the MM2 and AM1 data. AM1 was used in this particular part of the investigation due to its higher accuracy/sensitivity that will hopefully give closer results to experimental later on giving a closer comparison

| Energy in (kcal/mol) | ||

| Isomer A | Isomer B | |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.1054 | 0.7747 |

| Bend | 18.2943 | 13.1028 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.1073 | -0.0299 |

| Torsion | -15.7234 | -14.8249 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | 0.7285 | -1.6841 |

| 1,4 VDW | 14.3738 | 14.7254 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.6631 | 1.4083 |

| Total Energy (MM2) | 17.2228 | 10.6557 |

| Heat of Formation (AM1) | 143.4478 | 142.1451 |

NMR Calculation

The NMR's for Isomer A and B were calculated by minimizing the geometry through SCAN using the First method below and the NMR calculated with the second method listed below

# mpw1pw91/6-31g(d,p) opt(maxcycle=25)

# mpw1pw91/6-31(d,p) NMR scrf(cpcm,solvent=chloroform)

| Isomer A NMR Data: 13C NMR (Solvent CDCl3, Reference TMS), 1H NMR (Solvent CDCl3, Reference TMS),14N NMR (Solvent CDCl13, Reference NH3). | |||

|

|

|

DOI:10042/to-11765 |

| Isomer B NMR Data: 13C NMR (Solvent CDCl3, Reference TMS), 1H NMR (Solvent CDCl3, Reference TMS),14N NMR (Solvent CDCl3, Reference NH3). | |||

|

|

|

DOI:10042/to-11768 |

13C NMR

Isomer A

| Data | Assignment | DFT Optimized Geometry of Isomer A | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Isomer B

| Data | Assignment | DFT Optimized Geometry of Isomer B | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Discussion

All the NMR data relatively fit the literature quite well with the differences being around 3ppm on average with one spiking up to 7.03ppm. In general all values are lower in ppm than the experimental, this could be due to computationally you cant get accurate solvent interactions effecting the peaks, therefore it could be as simple as not computing solvent de-shielding effects in real life. However for this is shows that computational is relatively accurate at predicting spectra.

From the 13C NMR it can seen to distinguish between the two isomers singular peak at a higher ppm in the Isomer B around 148ppm rather than in A the highest peak is around 138ppm. Apart from this there is little difference between the two with a large overlapping peak that will be unclear due to real life errors so its best to look for the higher peak out of the high density of peaks.

This higher peak at 148ppm the carbon bonding to the phenyl group of the compound. It has less electron density on carbon 11 in isomer A relative to carbon 9 on isomer B. Both carbons are the attaching carbons to the -Ph group. However in compound A carbon 9 is adajcent to the Nitrogen bonded to the -CH2Ph group which is electron donating therefore this electron rich nitrogen can push electron density onto 9 increasing shielding and loweing ppm. In isomer B carbon 11 is bonded to a non-substituted Nitrogen which will draw electron density from the carbon lowering the shielding and increasing the ppm.

Testing the hypothesis

In this section, the idea of distinguishing the isomers by 13C NMR will be put to the test. A new set of data taken from the literature[22] of Isomer B is going to be plotted again the gaussian outputs of each isomer to determine which Isomer it is.

| Data | Bar Graph Plotting Differences Between Liuterature and Gaussian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

As you can see from the graph it shows that there are similar differences for most the data slightly lying towards the favour of B then the last peak as mentioned in the discussion there is a very large difference between the last peak and A's calculated last peak. Therefore it is confirmed that you can distinguish isomers A and B via NMR mostly using the higher ppm peak.

Other Computational Analysis

Vibrational Spectrum Analysis

The Vibrational spectra were calculated by the following method. They are tabulated after the method.

# b3lyp/6-31G(d,p) opt freq

| Vibrational Spectra of Isomer A | Vibrational Spectra of Isomer B |

|

|

As you can see from each vibrational spectra, there is no hihgly distinguishable difference between the two. The only intensities that could be used to distingish the isomers is the shifted N=N stretch, at 1282.51cm-1 on Isomer A and 1309.30cm-1.

UV-Vis Spectrum Analysis

| UV/Vis Spectra of Isomer A | UV/Vis Spectra of Isomer B |

|

|

From the UV/Vis Spectra it can be seen both isomers give very similar peaks. The two large absorptions for each compound are:

- Isomer A = λ1=230.8nm and λ2=180.0nm

- Isomer B = λ1=237.2nm and λ2=181.4nm

From these absorptions it can be said that it would be hard to tell the two isomers apart via UV/Vis. Near impossible with the larger peak in the high wavelength range and still quite difficult with the second smaller peak. With a difference of 6.4nm if there was any error in concentrations of the samples sent to UV the difference could easily be masked by different intensity peaks.

Conclusion

Depending on the concentration of copper or ruthenium you get a high regioselectivtiy for this process, teh reason for this is due to mechanistics and cannot be calculated via simple computational modules and requires studying the catalytic cycles of each process. However you can find out which Isomer you have via spectroscopic data. The main difference in the isomers is the high ppm shift in B, however there are other more subtle differences such as the shift in the N-N stretch in the IR data and the small lowering the of higher energy absorption in the UV/vis in Isomer B. The underlying message from this project however is the accuracy to which computational can predict 13C MNR and the realistic IR and UV spectra. With the NMR being reasonably accurate.

Summary of Module 1

From this module I believe it has been shown that computational chemistry can be applied to a wide sections of chemistry with relative success. Starting with molecular mechanic based parameters giving real insight to preferred sterics of compound allowing the analysis of a reaction going via a thermodynamic pathway or a kinetic pathway. However this can be built upon in more sophisticated systems were a quantum based parameter must be used to really find the true stability of a compound through wavefunctions, and even with all its assumptions give very accurate results in terms of selectivity for a reaction. The contest between the two methods is strong but in nearly all cases they still give the same trend with one compound coming out sterically and electronically favorable showing that they should be used in tandem to check each others results as well as improve on each others results.

References

- ↑ Young D. Computational Chemistry Wiley-Interscience, 2001. Appendix A. A.3.2 pg 342, MOPAC

- ↑ Wu, Zhijun. Lecture Notes on Computatlonal Structrual Biology, World Scientific Publishing, 2008.

- ↑ Hill, A.F. Organotransition Metal Chemistry Wiley-InterScience: New York, 2002: pp. 136–139.

- ↑ Synthesis in the hydroaromatic series, IV. Announcement: The rearrangement of malein acid anhydride on arylated diene, triene and fulvene, Diels, O.; Alder, K. Ber. 1929, 62, 2081 & 2087.

- ↑ Baldwin, J. E., "Cycloadditions. IX. Mechanism of the Thermal Interconversion of exo- and endo-Dicyclopentadiene", J. Org. Chem., 1966, 31(8), pp. 2441-44, DOI: 10.1021/jo01346a003

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Clayden, J., Greeves, N., Warren, S., Wothers, P., "Organic Chemistry", 2001

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Wilhelm F. Maier, Paul Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ E. Hückel, Zeitschrift für Physik, 70, 204, 1931; 72, 310, 1931; 76, 628 1932; 83, 632, 1933

- ↑ R. Hoffmann, Journal of Chemical Physics 1963 39 pp1397

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ Emil Fischer . Ueber die Glucoside der Alkohole. Ber. 1893 26(3): 2400–2412. DOI:10.1002/cber.18930260327.

- ↑ Juaristi, E., Cuevas, G. Recent studies of the anomeric effect Tetrahedron 1992 48(24) pp.5019–5087 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90118-8

- ↑ D. M. Whitfield, T. Nukada, Carbohydr. Res., 2007, 342, 1291. DOI:10.1016/j.carres.2007.03.030

- ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:organic

- ↑ Sharpless K. B., Kolb H. C., Finn M.G, Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2001 40(11) pp. 2004-2021 DOI:<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5

- ↑ Evans R. A. The Rise of Azide–Alkyne 1,3-Dipolar 'Click' Cycloaddition and its Application to Polymer Science and Surface Modification Australian Journal of Chemistry 2007 60(6) pp. 384-395 DOI:10.1071/CH06457

- ↑ Huisgen R. Centenary Lecture - 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions Proceedings of the Chemical Society of London 1961 60(6) pp. 357 DOI:10.1039/PS9610000357

- ↑ Sharpless, K. B., Rostovtsev, V. V., Green, L. G., Fokin, V. V., "A Stepwise Huisgen Cycloaddition Process: Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective "Ligation" of Azides and Terminal Alkynes", Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2002, 41 (14), pp. 2596-99

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Coelho, A., Diz, P., Caamaño, O. and Sotelo, E. (2010), Polymer-Supported 1,5,7-Triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene as Polyvalent Ligands in the Copper-Catalyzed Huisgen 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition. Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis, 352: 1179–1192. DOI:10.1002/adsc.200900680

- ↑ Sharpless, K., Fokin, V., Jia, G., "Supporting Information for Ruthenium-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Alkynes and Organic Azides", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2005, 127 DOI:10.1021/ja054114s

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Alonso F., Moglie Y., Radivoy G. Yus M., Unsupported Copper Nanoparticles in the 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of Terminal Alkynes and Azides, European Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2010 pp 1875-1884 DOI:10.1002/ejoc.200901446