Rep:Mod:irb10

Isaid Benitez Cabral

Computational Laboratory 2013 Physical Module: Transition States and Reactivity

Introduction

Computational chemistry lies at the forefront of modern chemical research. Computational techniques allow chemists to calculate important molecular properties, without the need to get their hands dirty. Computational techniques allow us to locate the transition states for a reaction, predict vibrational spectra and important thermochemical quantities. The calculations of energy properties are of comparable accuracy to experimental determinations. At the heart of everything lies the Schroedinger Equation and molecular wavefunctions. The importance of computational chemistry in modern science is illustrated by the fact that the 2013 Nobel Prize was awarded to tree computational chemists 'for the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems'.

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

The Cope rearrangement is a [3,3]-sigmatropic shift rearrangement. In this exercise, we are going to locate the transition states for the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene.

Optimizing the reactants

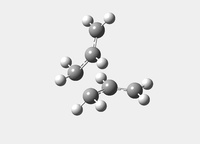

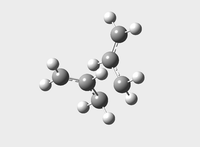

The first step is to optimise the reactants. We talk about reactants, in the plural, because 1,5-cyclohexadiene can adopt a number of conformations, which arise as a result of rotation about single bonds. There are two main conformational types, which we call here 'anti' and 'gauche'. These are illustrated in the following figure:

We expect the gauche conformers to have a higher energy than the anti conformers. Steric repulsion between the two 'ethene' groups is minimised when they are found in an antiperiplanar relationship, which leads to the anti conformers having a lower energy.

Three conformers were drawn, two anti and one gauche, and optimised using the Hartree-Fock method and a 3-21G basis set. This is the default method. The following results were obtained:

anti1

Total Energy = -231.69260236 a.u.

Point Group: C2/C1

anti2 - first optimisation

Total Energy = -231.69253516 a.u.

Point Group: Ci

gauche4

Total Energy = -231.69153035 a.u.

Point Group: C2/C1

Lowest energy structure is anti2. We proceeded to re-optimise this conformer at the more sophisticated B3LYP level, making use, this time, of a 6-31G* basis set. B3LYP calculations belong to the family of Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. The results are shown below:

anti2 - second optimisation

Total energy:

-234.61170273 a.u.

The total energy was lower after this second, more sophisticated, optimization. The overall geometry is almost identical. The dihedral angle between the central four carbon atoms was unchanged. There were very small variations in the 'triatomic' angles.

No imaginary frequencies appear in the predicted vibrational spectrum, as expected.

anti2 - frequency calculation

We proceeded to run a frequency calculation, in order to obtain useful thermochemical data that we can compare to experimental values.

Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies: -234.469212 a.u.

Sum of electronic and thermal Energies: -234.461856 a.u.

Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies: -234.460912 a.u.

Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies: -234.500822 a.u.

Optimizing the 'Chair' and 'Boat' Transition Structures

In order to locate the chair transition state we cut 1,5-hexadiene in half. We drew and optimised an allyl fragment and proceeded to copy and paste two allyl fragments into a new file and position them such that they resembled the chair transition structure, with the distances between the terminal ends of the ally fragments as close to 2.2 Å as possible. This is where bond making and breaking occurs. This guess chair transition state structure is our input file for the optimisation.

Allyl fragment

Chair transition state guess structure

Distances between terminal ends of allyl fragments:

B = 2.19427 Å (C1 C9) B = 2.21589 Å (C6 C14)

Optimising chair transition state - Berny method

In order to locate the chair transition structures, we used a number of methods. The simplest method is the Berny method. The Berny method works only if the guess transition state structure is close to the real transition state structure.

After running a Berny optimisation we found one imaginary frequency of magnitude -817.90 cm-1 appears in the predicted vibrational spectrum. This observation confirms that the optimized structure corresponds to a transition state. The animation of the vibration corresponding to the imaginary frequency is shown below:

The animation clearly shows that we have indeed found the transition state for the [3,3]-sigmatropic shift rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene. We can follow the bond making and breaking of the Cope rearrangement easily by eye.

Distances between terminal ends of allyl fragments:

B = 2.02051 Å B = 2.02057 Å

Optimising chair transition state - Frozen coordinates method

The second method we used is the frozen coordinates method. This method proceeds in two steps. In the first step we select two coordinates, here the distances between the terminal ends of the allyl fragments i.e. where bond making and breaking occurs, and 'freeze' them. We then carry out an optimisation as in the Berny method. In the second step, we unfreeze the coordinates and run a second optimisation. The settings change from the first step to the second step, for example instead of 'freeze coordinates' we choose 'derivative' and we refrain from calculating force constants.

The structure we obtain with the frozen coordinates method is almost identical to the one obtained with the pure Berny method. The energy differs by 0.00000001 a.u.

Optimising boat transition state - QST2 and QST3

In order to optimise the boat transition state, we used a different method than that used for the chair transition state. In the QST2 method we specified the reactants and product and the calculation determined the transition state. In the QST3 method, we additionally specified a guess transition state. These calculations took a longer time to complete than the Berny optimisations.

The initial QST2 calculation failed:

The QST2 calculation was re-run after bringing the reactants and product structures to look more like the boat transition state.

The animation of the vibration corresponding to the imaginary frequency is shown below:

A QST3 calculation was run straight after the successful QST2. The same result was obtained, but the calculation itself took a longer time to run.

Optimising chair transition state - Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate

This fourth method allows us to follow the minimum energy path from a transition structure down to its local minimum on a potential energy surface. We ran the IRC with n=50 and obtained 44 intermediates. We re-ran it, this time with n=100 and obtained the same number of intermediates. In a third rerun we changed the settings to calculate force constants at every step. This last rerun took longest.

B3LYP/6-31G* Re-optimization

In order to calculate the activation energies for the rearrangement via the chair and boat transition structures, we ran a second optimisation of the transition structures we located using the methods explained above.

Chair transition state:

Total Energy: -234.55698298 a.u.

Boat transition state:

Total Energy: -234.54309304 a.u.

The geometry is identical.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels Alder reaction is a [4+2] cycloaddition of a conjugated diene and dienophile. The mechanism is concerted. The reaction is stereo- and regio selective.

(i)Drawing and optimizing cis-butadiene and ethene

Cis-butadiene and ethene were drawn and optimised using the semi-empirical AM1 method. The HOMOs and LUMOs of both molecules were visualised:

Cis-butadiene HOMO:

anti-symmetric

(ii)Computing the transition state geometry for the prototype reaction

The transition state for the prototype reaction of cis-butadiene and ethene was located using the Berny method.

Distances pre-optimisation: B = 1.94639 Å (C8 C14) B = 1.74254 Å (C1 C11)

Distances post-optimisation: B = 2.20946 Å (C8 C14) B = 2.20960 Å (C1 C11)

'Distances' above refer to distances between carbon atoms where bond making occurs on two molecules.

Three views of the transition state 'HOMO':

HOMO is antisymmetric with respect to plane.

Typical C-C distances2:

C(sp3)-C(sp3) = 1.53 Å C(sp2)-C(sp2) = 1.48 Å

Vibration corresponding to bond making:

Vibration corresponding to first real vibration:

(iii)Studying the regioselectivity

Endo transition state:

Total Energy: -605.61036808 a.u.

Imaginary frequency of magnitude -643.30 cm-1 observed.

Exo transition state:

Total energy: -605.60359125 a.u.

Imaginary frequency of magnitude -647.47 cm-1 observed.

The energy of the exo isomer is higher than that of the endo regioisomer, as expected.

Three views of the exo HOMO:

C-C bond making distances in exo transition state:

2.26075 (C5 C6) 2.26068 (C1 C9)

C-C through-space distances in exo transition state:

2.91624 (C2 C10) 2.91627 (C4 C11)

Three views of the endo HOMO:

C-C bond making distances in endo transition state:

2.23049 (C1 C6) 2.23156 (C2 C9)

C-C through space distances in endo transition state:

2.84836 (C3 C8) 2.84745 (C5 C7)

Secondary orbital effects are what cause the endo to be lower in energy. There are favourable interactions between the maleic anhydride oxygen p orbitals and the p orbitals on the diene. This also explains why the 'through-space' distances are lower in the endo.

References

1. Guy H. Grant, W. Graham Richards Computational Chemistry

2. Matthew S. Platz, Robert A. Moss, Maitland Jones, Jr. Reviews of Reactive Intermediate Chemistry