Rep:Mod:hy2b

Module 2: Inorganic – Mini project (Holly Yu)

Introduction

This project aims to determine which isomer of platin (cisplatin or transplatin) is of lower energy, and to rationalise this finding by analysis of the two compounds’ geometry, vibrational modes, frontier orbitals, and also using natural bond orbital theory.

Synthetically, the geometry of platin formation is governed by the trans effect. This is a kinetic phenomenon, which depends on the sigma donating/accepting ability of ligands trans to the site of substitution, generally on a square planar complex.

This project will be split into three sections:

1) analysis of the relative energies of cis and trans platin, to determine which isomer is the most energetically stable, followed by a natural bond and frontier orbital analysis of a potential precursor en route to platin formation, to determine the most likely site of nucleophilic attack and the most likely leaving group.

2) taking the trans effect into account, a ligand found to have a stronger trans effect than the chloride ligands will be analysed, to determine whether computational results agree with those documented widely in the literature. Again, a frontier orbital and NBO analysis of the potential platin precursor will be analysed.

3) taking the trans effect into account, a ligand experimentally found to have a weaker trans effect than the chloride ligands will be analysed, to determine whether computational results agree with those documented widely in the literature. Again, a frontier orbital and NBO analysis of the potential platin precursor will be analysed.

The ligands chosen in each case are monoanionic, small ligands, which should hopefully result in only minor steric differences between the ligands, meaning that the effects observed and interpreted below should arise solely due to electronic effects.

A related effect to the trans effect is trans influence. This is a structural phenomenon, and concerns how ligands trans to other ligands influence bond angles and geometry within a complex. The trans influence of ligands within the compounds below will also be analysed for each of the compounds detailed below.

Overview of the trans effect

The trans effect refers to the labilisation of a ligand in a trans position to another specific ligand[1]. It is related to the sigma donating ability of a ligand towards a metal centre. An empirical ordering of the trans effect for ligands (measured by looking at the relative rates of ligand substitution with different ligands present), has been found to be as follows:

F−, H2O, OH− < NH3 < py < Cl− < Br− < I−, SCN−, NO2−, SC(NH2)2, Ph− < SO32− < PR3, AsR3, SR2, CH3− < H−, NO, CO, CN−, C2H4

In the reactions studied below, three different types of ligand will be analysed: I-, Cl- and OH-. Looking at the ordering given above, it is expected that the I- will exert a stronger trans effect, and thus a faster rate of substitution, than both Cl- and OH-, and that Cl- will exert a stronger trans effect than OH-.

The trans effect is a kinetic phenomenon, and manifests itself via the stabilisation of transition states. This contrasts with the trans influence, which concerns reactant destabilisation via e.g. increasing bond lengths, corresponding to weakened, more reactive bonds.

Overview of trans influence

The trans influence can be defined as the effect which a coordinated ligand exerts on a ligand trans to it, on a metal centre. This trans influence can generally be seen in square planar complexes, and is particularly prevalent for Pt(II) complexes. Unlike the trans effect, which is a kinetic effect concerning the rate of ligand substitution, the trans influence is a thermodynamic effect, influencing bond lengths and vibrational frequencies.[2]

The trans effect can be thought of in molecular orbital terms as two ligands, situated trans to each other on a metal centre, competing for a single unoccupied metal orbital. The more strongly σ-donating ligand will win out over the less strongly σ-donating ligand, resulting in a weakening of the metal to the latter’s bonding.

An empirical trans influence scale has been determined to be as follows:[3]

O < N < F < P < Cl < Br < I

This order seems to mirror the trans effect ordering of ligands. The trans effect and trans influence have similar outcomes, in that a greater trans influence will weaken the metal-substituent bond trans to the ligand showing the trans influence. This weakened bond will then be more susceptible to substitution, which can be correlated to a greater trans effect.

Research has found that for complexes containing Pt-Cl bonds, strong σ-donors will show a strong trans influence by increasing the partial observed charges on both the Pt and Cl, which results in an increase in electrostatic repulsion between the two and thus a lengthened, weaker bond. The extent of the trans influence on Pt-Cl bonds can be exemplified by research which found a bond length of between 2.25Å and 2.43Å with various different trans ligands.

A note on errors and accuracy

Several factors must be taken into account when analysing the results of the calculations. Errors on the energy are on the order of 10 kJ mol-1. Converting this to atomic units (hartree) gives an error of 0.00381 hartree. The accuracy of the dipole moment is around 2 decimal places, and the frequencies are only correct to within around 10%, due to the use of a harmonic approximation when the vibrations observed are actually anharmonic. Similarly, the calculated intensities are only accurate to within one integer, bond lengths to within 0.01Å and bond angles to 0.1o. All of these factors mean that the results obtained during these calculations cannot be taken to be definitive values.

These factors will be taken into account when interpreting the results from the optimisations below.

Cis- and trans-platin

Creating and optimising the cis- and trans-platin structures

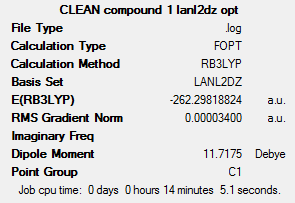

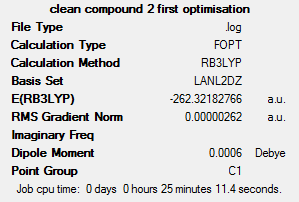

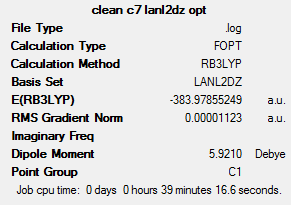

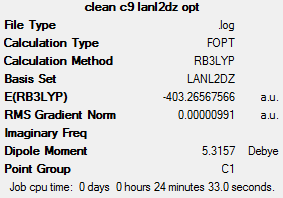

Compounds 1 and 2 were drawn on Gaussview, before optimising their structures using a B3LYP method and an LANL2DZ basis set. This is a medium-level basis set suitable for heavy atoms, such as Pt. Additional options used were “int=ultrafine scf=conver=9”. This gave the following optimised structures, geometries and summaries:

This shows that transplatin has a slightly lower energy (0.0236 hartree, or 61.96 kJ mol-1) than cisplatin. Cisplatin is much more physiologically active than transplatin; one reason for this may be due to it being higher in energy than transplatin, meaning there is a smaller energy barrier to the transition state along the physiological pathway. Transplatin’s stability may be due the fact that in cisplatin, the strongly electron-withdrawing chloride ligands exert a dipole moment in the same direction, meaning the complex is on average more polarised than the corresponding transplatin. Additionally, the large chloride ligands may experience slight steric clashes in the cis conformer, which are avoided in the trans conformer. Overall this gives rise to the fact that the trans conformer is of a lower energy than the cis conformer.

| Cis isomer (compound 1) | Trans isomer (compound 2) | |

|---|---|---|

| LANL2DZ logfile | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6667 | |

| Jmol of optimised structure | ||

| Frequency analysis logfile |

| Geometric parameter | Cis isomer (compound 1) | Trans isomer (compound 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Cl-Pt-Cl angle (o) | 96.8 | 180.0 |

| Cl-Pt-N angle (o) | 82.0 (cis) | 91.3 |

| Cl-Pt-N angle (o) | 178.7 (trans) | |

| N-Pt-N angle (o) | 99.3 | 180.0 |

| Pt-Cl bond length (Å) | 2.41 | 2.43 |

| Pt-N bond length (Å) | 2.11 | 2.07 |

The results from the geometric analysis show that the Pt-Cl bond lengths are slightly longer in the trans isomer, whereas the Pt-N bond lengths are slightly shorter in the trans isomer. Looking at the cis isomer, and taking the trans influence into account, this supports the fact that the chloride ligands show a stronger trans influence than the NH3 ligands, resulting from the Cl substituents donating more electron density to the Pt via σ-donation. This then enables the Pt to transfer electron density to the N atoms, resulting in a longer bond (the strength of which, relative to that in the trans isomer, will be analysed below).

The Cl-Pt-Cl angle in the cis isomer, which is greater than the 90o angle found in an idealised square planar compound, suggests electrostatic repulsion between the two Cls, resulting in an increased bond angle to reduce these electrostatic interactions. Although this would then bring the Cl substituents in closer proximity to the NH3 ligands, the loss of Cl-Cl electrostatic repulsion must outweigh the increased Cl-NH3 repulsion. This new Cl-NH3 repulsion may be either steric (as the N atom has 3 H atoms bound, which will be constantly rotating around the N atom), or electrostatic, though the electron cloud associated with the nitrogen will surely be smaller than that of the chlorines, due to it containing fewer electrons.

Performing a frequency analysis on cis and trans platin

In order to analyse the relative bond strengths in the cis and trans isomers, to see whether they correlated to the bond lengths shown above, a frequency analysis was performed on the LANL2DZ optimised structures.

Additional keywords used for this were “int=ultrafine scf=conver=9”. No negative frequencies were detected, meaning that the optimised structures were indeed energy minima, and the subsequent vibrational analysis is valid.

This gave the following results:

| Mode | Animation of vibration (compound 1) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | Mode | Animation of vibration (compound 2) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 |

|

320 | 25 | 8 |

|

300 | 0 | ||||||

| 9 |

|

330 | 25 | 9 |

|

328 | 53 | ||||||

| 10 |

|

463 | 14 | 10 |

|

509 | 6 | ||||||

| 11 |

|

468 | 2 | 11 |

|

526 | 0 |

It can be seen from the table that the Pt-N stretching frequencies in the cis isomer are significantly lower than those in the trans isomer. This supports the trans influence explanation given above; that the chloride ligands donate more electron density to the Pt centre, which consequentially weakens the trans Pt-N bond. The Pt-Cl stretches in each isomer are fairly similar, but are marginally higher in the cis complex. Again, this can be attributed to the Cl ligands donating more electron density to the Pt centre (thus resulting in a stronger bond between the two, and an increase in stretching frequencies). In the trans isomer, the Cl ligands are trans to each other, meaning that the trans effect will not be observed.

Creating and optimising the trichloro precursor

Compound 3 was drawn on Gaussview, before optimising its structure using a B3LYP method and an LANL2DZ basis set. Additional keywords used were “int=ultrafine scf=conver=9”. The negative charge of the complex was added manually prior to the optimisation. This gave the following optimised structure and geometry:

| Compound 3 | |

|---|---|

| LANL2DZ logfile | |

| Frequency analysis logfile | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6680 |

| Jmol of optimised structure |

| Geometric parameter | Trichloro precursor (compound 3) |

|---|---|

| Cl-Pt-Cl angle (o) | 180.0 (trans) |

| Cl-Pt-Cl angle (o) | 90.0 (cis) |

| Cl-Pt-N angle (o) | 90.0 |

| Pt-Cl bond length (Å) | 2.28 |

| Pt-N bond length (Å) | 1.99 |

Taking into account the scheme proposed in the introduction for the synthesis of compound 1 or 2 from compound 3, a Cl- ligand will be replaced with an NH3 ligand. In this case, the Pt-Cl bonds are all longer than those found in compounds 1 and 2, suggesting weaker bonds which will be more susceptible to substitution reactions. Surprisingly, the Pt-N bond length is shorter than those found in cis- and trans-platin, suggesting a stronger bond. The bond angles support an ideal square planar geometry, with no distortion due to steric or electronic effects.

Performing a frequency analysis on the trichloro precursor

A frequency analysis was performed on compound 3, again using the B3LYP method and LANL2DZ basis set. The additional keywords used above were retained.

| Mode | Animation of vibration | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 |

|

402 | 2 | |||

| 8 |

|

422 | 22 | |||

| 9 |

|

439 | 58 | |||

| 13 |

|

1277 | 220 |

A molecular orbital comparison of compounds 1, 2 and 3

Analysis of the molecular orbitals of compounds 1, 2 and 3 may enable some information to be gleaned about potential sites of nucleophilic attack for substitution reactions, or to rationalise the relative stabilities of the complexes:

| Molecular orbital | Compound 1 | Compound 2 | Compound 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| LUMO+1 |  |

|

|

| LUMO |  |

|

|

| HOMO |  |

|

|

| HOMO-1 |  |

|

|

Overall, relatively little difference can be seen between the LUMOs of each of the compounds, though the HOMO of compound 3 has higher regions of electron density on the two Cls trans to each other. This may mean that they would be better leaving groups in a substitution reaction. This supports the principles behind the trans effect, which in this case would lead to loss of a Cl ligand cis to the NH3.

The HOMO of compound 1 illustrates the large electron clouds associated with the Cl ligands which results in an increase in the Cl-Pt-Cl angle in the cis conformer, to reduce electrostatic repulsions as detailed earlier.

A Natural Bond Orbital comparison of compounds 1, 2 and 3

Performing a natural bond orbital analysis of compounds 1, 2 and 3 results in the following charges being assigned to each atom:

This basic NBO analysis shows that the two chlorides are equivalent in compound 1, and that the 2 NH3 ligands are also equivalent in compound 1. Similarly, in compound 2, the two Cls have the same atomic charge, as do the two NH3s. This means that in compound 1 the two Cls are chemically equivalent, and this is also the case in compound 2. A similar conclusion can be drawn for the NH3 ligands in compounds 1 and 2, respectively. Compound 3, on the other hand, shows a marked difference between the atomic charges on the Cl atoms. In this case, the two Cls cis to the NH3 have higher partial negative charges then the Cl trans to the NH3. This suggests that the cis Cls would be better leaving groups upon reaction and subsequent substitution with NH3, as they are closer to attaining the full 1- negative charge required to form the Cl- leaving group. The NBO analysis has therefore allowed determination of the most likely site for substitution to occur at.

(NB although the nitrogen has a much higher partial negative charge than any of the Cls, this is countered by the surrounding partial positive charges of the 3 Hs, resulting in an effectively electrically neutral ligand).

The results of the NBO analysis therefore support the trans effect, which proposes that a Cl ligand cis to the NH3 would undergo substitution, as Cl displays a greater trans effect than NH3.

The results also provide an example of the trans influence. Comparing compounds 1 and 2, it can be seen that there is a less negative partial charge on the Cls in compound 1, the cis compound, than in compound 2, the trans compound. Compound 1 also displays a higher partial negative charge on the N atom compared to that found in compound 2. This suggests a higher degree of the Cl- ligand’s full negative charge has been donated via σ-donation to the Pt centre, which can then transfer electron density to the NH3 substituent. This trans influence is not seen in compound 2, as the ligands trans to each other are equivalent.

Iodo-analogues of cis- and trans-platin

Creating and optimising the iodo-analogues of cis- and trans-platin

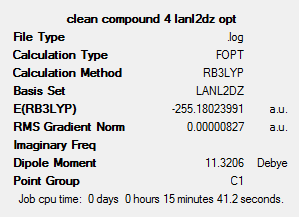

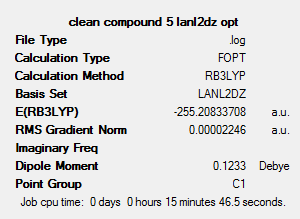

Compounds 4 and 5 were drawn on Gaussview, before optimising their structures using a B3LYP method and an LANL2DZ basis set. This is a medium-level basis set suitable for heavy atoms, such as Pt. Additional options used were “int=ultrafine scf=conver=9”. This gave the following optimised structures, geometries and summaries:

This shows that trans isomer, compound 5, has a slightly lower energy (0.0281 hartree, or 73.78 kJ mol-1) than the cis isomer. This could be due to similar reasons as for the chloro-substituted compound – i.e. steric clashes are minimised in the trans isomer, and there is a lower overall dipole moment in the trans isomer, leading to a reduced reactivity and thus a higher stability.

| Cis isomer (compound 4) | Trans isomer (compound 5) | |

|---|---|---|

| LANL2DZ logfile | ||

| Jmol of optimised structure | ||

| Frequency analysis logfile | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6682 |

| Geometric parameter | Cis isomer (compound 4) | Trans isomer (compound 5) |

|---|---|---|

| I-Pt-I angle (o) | 94.0 | 179.4 |

| I-Pt-N angle (o) | 85.7 (cis) | 89.7 |

| I-Pt-N angle (o) | 179.7 (trans) | |

| N-Pt-N angle (o) | 94.6 | 179.4 |

| Pt-I bond length (Å) | 2.69 | 2.73 |

| Pt-N bond length (Å) | 2.15 | 2.08 |

The bond lengths above follow the trend shown in cis and trans platin, again suggesting the trans influence is being observed. This is manifested in the shorter Pt-I bond length, and longer Pt-N bond length, in the cis isomer, as opposed to the trans isomer. Again, in the cis isomer, the I-Pt-I angle, and the N-Pt-N angle, are larger than the ideal square planar bond angle of 90o. This widening of bond angles can act to alleviate electrostatic interactions between filled electronic orbitals, resulting in a more stable conformation.

Performing a frequency analysis on the iodo analogues of cis and trans platin

| Mode | Animation of vibration (compound 4) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | Mode | Animation of vibration (compound 5) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 |

|

168 | 9 | 5 |

|

132 | 0 | ||||||

| 7 |

|

176 | 2 | 7 |

|

181 | 32 | ||||||

| 10 |

|

415 | 24 | 10 |

|

502 | 2 | ||||||

| 11 |

|

430 | 9 | 11 |

|

520 | 0 | ||||||

| 16 |

|

1329 | 475 | ||||||||||

| 17 |

|

1329 | 0 |

The longer Pt-I bonds seen in the trans complex are in agreement with the lower vibrational frequencies of the bonds shown in the table above. Similarly, the strength of the longer Pt-N bonds in the cis isomer can be defined as weaker than the corresponding bonds in the trans isomer, due to the lower vibrational frequencies seen for the cis isomer.

Creating and optimising the triiodo precursor

Compound 6 was drawn on Gaussview, before optimising its structure using a B3LYP method and an LANL2DZ basis set. Additional keywords used were “int=ultrafine scf=conver=9”. The negative charge of the complex was added manually prior to the optimisation. This gave the following optimised structure and geometry:

| Compound 6 | |

|---|---|

| LANL2DZ logfile | |

| Frequency analysis logfile | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6683 |

| Jmol of optimised structure |

| Geometric parameter | Triiodo precursor (compound 6) |

|---|---|

| I-Pt-I angle (o) | 180.0 (trans) |

| I-Pt-I angle (o) | 90.0 (cis) |

| I-Pt-N angle (o) | 90.0 |

| Pt-I bond length (Å) | 2.62 |

| Pt-N bond length (Å) | 1.99 |

Taking into account the scheme proposed in the introduction for the synthesis of compound 4 or 5 from compound 6, an I- ligand will be replaced with an NH3 ligand. Compound 6 contains shorter Pt-I and Pt-N bonds than the cis and trans isomers 4 and 5. This is unexpected: the complex, compound 6, is monoanionic, and it would be expected that all the bond lengths within the complex would be lengthened slightly to minimise electrostatic repulsions and provide a ‘larger’ compound for the charge to delocalise across.

Performing a frequency analysis on the triiodo precursor

| Mode | Animation of vibration | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 |

|

161 | 0 | |||

| 8 |

|

200 | 5 | |||

| 9 |

|

222 | 23 | |||

| 13 |

|

1245 | 236 |

Compound 6 shows similar Pt-I stretching frequencies as the cis and trans isomers, compounds 4 and 5, but the Pt-N stretching frequency seems anomalously high. This may be due to the use of only a medium-level basis set. Heavier atoms require higher level basis sets, though these require more computational power and longer computational times. The presence of three heavy I- ligands may have affected the calculations performed in this case.

A molecular orbital comparison of compounds 4, 5 and 6

| Molecular orbital | Compound 4 | Compound 5 | Compound 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| LUMO+1 |  |

|

|

| LUMO |  |

|

|

| HOMO |  |

|

|

| HOMO-1 |  |

|

|

As was the case for the chloro complexes above, very little can be deduced from the MOs shown above. The LUMOs differ little between the complexes.

A Natural Bond Orbital comparison of compounds 4, 5 and 6

For compounds 4 and 5, the same trend, as discussed for compounds 1 and 2 above, is seen, i.e. a trans influence is present in the cis isomer, compound 4. Analysing compound 6 in terms of the trans effect, it is expected that the iodide ligands would exert a stronger trans effect than the chloride ligands in compound 3, in line with experimental evidence.

This seems to be the case:

In compound 3, the charge of the Cl trans to the NH3 is around 86% that of the charge found on the Cls cis to the NH3.

In compound 6, the charge of the I trans to the NH3 is only around 70% that of the charge found on the Is cis to the NH3. This means that the Is cis to the NH3 are more strongly favoured as leaving groups relative to the I trans to the NH3, than the Cls cis to the NH3 relative to the Cl trans to the NH3. This correlates well with the ideas behind the trans effect.

Hydroxyl-analogues of cis- and trans-platin

Creating and optimising the hydroxyl-analogues of cis- and trans-platin

Compounds 7 and 8 were drawn on Gaussview, before optimising their structures using a B3LYP method and an LANL2DZ basis set. This is a medium-level basis set suitable for heavy atoms, such as Pt. Additional options used were “int=ultrafine scf=conver=9”. This gave the following optimised structures, geometries and summaries:

The two compounds have very similar energies – the trans isomer is marginally more stable (0.0000985 hartree, 0.26 kJ mol-1).The complexes are much more similar in energy than the compounds analysed above. Such a low energy difference suggests that isomerisation between the compounds is probably occurring at room temperature.

| Cis isomer (compound 7) | Trans isomer (compound 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| LANL2DZ logfile | ||

| Jmol of optimised structure | ||

| Frequency analysis logfile |

| Geometric parameter | Cis isomer (compound 7) | Trans isomer (compound 8) |

|---|---|---|

| O-Pt-O angle (o) | 100.9 | 180.0 |

| O-Pt-N angle (o) | 75.7 (cis) | 76.3 (cis) |

| O-Pt-N angle (o) | 176.2 (trans) | 103.7 (cis) |

| N-Pt-N angle (o) | 107.7 | 180.0 |

| Pt-O bond length (Å) | 2.03 | 2.06 |

| Pt-N bond length (Å) | 2.11 | 2.08 |

The overall trend is as seen above for the two previous reaction schemes: a longer Pt-N bond in the cis isomer than the trans isomer, and a shorter Pt-E (where E = Cl, I or O) bond in the cis isomer. However, in this case the results cannot be rationalised using the trans influence, as in the empirical table of ligands’ effects for the trans influence, oxygen comes below nitrogen. This means it would be expected that nitrogen would exert a trans influence on the oxygens trans to it, resulting in longer Pt-O bonds and shorter Pt-N bonds.

This is not the case. One possible factor which may explain this is that hydrogen-bonding is occurring in the complex. This can be seen extensively in the animated vibrations below. In terms of the geometry of compounds 7 and 8, it can be seen that there are in fact two O-Pt-N angles for each complex. This occurs as a direct result of hydrogen bonding between the O of the hydroxyl ligands, and a H from the NH3 ligand. This acts to contract one of the O-Pt-N angles, and also results in a concerted expansion of the corresponding O-Pt-N angle.

The fact that hydrogen bonding is occurring is unfortunate, as this means that the results calculated below will show a degree of bias when analysing the geometries and vibrational frequencies, relative to the non-hydrogen bonding I- and Cl- ligands. The hydroxyl ligand was chosen as it lay below Cl- in the spectrochemical series, and was monoanionic, thus resembling both Cl- and I- in that aspect.

Performing a frequency analysis on the hydroxyl analogues of cis and trans platin

| Mode | Animation of vibration (compound 7) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | Mode | Animation of vibration (compound 8) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 |

|

458 | 4 | 10 |

|

490 | 12 | ||||||

| 11 |

|

471 | 1 | 11 |

|

507 | 0 | ||||||

| 12 |

|

552 | 73 | 12 |

|

532 | 0 | ||||||

| 13 |

|

566 | 58 | 13 |

|

532 | 118 | ||||||

| 21 |

|

1261 | 127 | 20 |

|

1253 | 563 | ||||||

| 21 |

|

1255 | 2 |

The lower frequency Pt-N stretches, and higher frequency Pt-O stretches in the cis compound (relative to those in the trans compound) are in agreement with the bond lengths defined above. Overall, the two spectra show strong similarities, more so than those for the Cl and I derivatives shown above.

Creating and optimising the trishydroxyl precursor

Compound 9 was drawn on Gaussview, before optimising its structure using a B3LYP method and an LANL2DZ basis set. Additional keywords used were “int=ultrafine scf=conver=9”. The negative charge of the complex was added manually prior to the optimisation. This gave the following optimised structure and geometry:

| Compound 9 | |

|---|---|

| LANL2DZ logfile | |

| Frequency analysis logfile | |

| Jmol of optimised structure |

| Geometric parameter | Trishydroxyl precursor (compound 9) |

|---|---|

| O-Pt-O angle (o) | 175.40 (trans) |

| O-Pt-O angle (o) | 87.1 (cis) |

| O-Pt-N angle (o) | 98.9 (cis) |

| O-Pt-N angle (o) | 173.8 (trans) |

| Pt-O bond length (Å) | 2.07 (cis to N) |

| Pt-O bond length (Å) | 2.02 (trans to N) |

| Pt-N bond length (Å) | 2.12 |

This compound is the only precursor analysed to display a difference in the Pt-E bond lengths (cis or trans to the NH3). In compounds 3 and 6, the Pt-E bond lengths are equal, whether they are trans or cis to the NH3 ligand.

The shorter Pt-O bond length, trans to the NH3 ligand, and the longer Pt-N bond length, could be used to argue that the OH ligand displayed a stronger trans influence than the NH3 ligand. This is not in agreement with the literature. The discrepancies observed are most likely due to the effects of hydrogen bonding; perhaps the literature trans effect concerns neutral O-bearing ligands such as H2O. However, if H2O were used, then the cis and trans complexes, 7 and 8, would be dicationic overall. This difference would perhaps have more of an effect on the overall analysis and interpretation, than the effect of hydrogen bonding on overall neutral complexes.

Performing a frequency analysis on the trishydroxyl precursor

| Mode | Animation of vibration | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 |

|

451 | 16 | |||

| 11 |

|

498 | 146 | |||

| 12 |

|

502 | 14 | |||

| 13 |

|

551 | 76 | |||

| 19 |

|

1116 | 319 |

This shows one major difference from an experimentally observed spectrum, which would doubtless display a broad absorption peak at around 3500 cm-1, owing to hydrogen bonding within the sample. In this calculated spectrum, all the absorption lines are relatively sharp, showing ideal situations.

A molecular orbital comparison of compounds 7, 8 and 9

| Molecular orbital | Compound 7 | Compound 8 | Compound 9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| LUMO+1 |  |

|

|

| LUMO |  |

|

|

| HOMO |  |

|

|

| HOMO-1 |  |

|

|

In this case, the frontier orbitals for compounds 7, 8 and 9 now show noticeable differences. The LUMO of compound 7, the cis isomer, is mainly symmetric, with no discerning features, whereas the LUMOs of compounds 8 and 9, the trans isomer and tris-hydroxyl precursor, respectively, show distinct nodal planes, with just two regions of electron density on ligands trans to each other.

Looking at the LUMO of compound 9, the fact that there is substantially more electron density on the OH group trans to the NH3 than the OH groups cis to the NH3 demonstrates that NH3 shows a stronger trans effect than OH, proving that OH is a weaker trans effect director than NH3.

A Natural Bond Orbital comparison of compounds 7, 8 and 9

This shows both charges on the O in compound 7 are equivalent, as are the charges on the N atoms. The same trend is seen in compound 8. Interestingly, the hydrogen-bonding is manifested in the charges present on the hydrogens of the NH3 oriented towards the O of the OH:

In compound 7, the two hydrogens (labelled as 12H and 13H) closest to the Os have charges of +0.417, whereas in compound 8, the trans isomer, the two hydrogens (labelled 10H and 12H) have charges of +0.412. This suggests that the hydrogens 12 and 13 in compound 7 are slightly more acidic than hydrogens 10 and 12 in compound 8.

Similarly, in compound 9, hydrogen 9 is much more acidic (+0.396) than the corresponding Hs on the same N atom (hydrogens 10 and 11, both with charges of +0.329).

In compound 9, it is expected that NH3 will display a stronger trans effect than OH, resulting in the OH trans to NH3 bearing the highest partial negative charge, as it should be the best potential leaving group (as OH-, with a full negative charge). However, this expectation is not observed; the OH trans to the NH3, and one of the OHs cis to the NH3, have almost identical charges, whereas the other OH cis to the NH3 shows a much more negative partial charge and therefore it would be expected that this OH would undergo substitution in preference to the others.

This is clearly not in line with the outcome predicted by either the trans influence or the trans effect, and can only be attributed to the complications which arise in analysis due to hydrogen bonding. It serves to reinforce the complications that hydrogen bonding can have on a system.

Conclusion

Overall, the calculations shown above for schemes 1 and 2 (compounds 1-6) seem to agree quite well with the ideas behind the trans influence and the trans effect, but scheme 3 agrees less well with the principles of trans influence and trans effect, most likely due to the hydrogen bonding present within compounds 7, 8 and 9.