Rep:Mod:hy2

Module 2: Inorganic (Holly Yu)

The following article covers the optimisation and analysis of the structures of several compounds. Gaussian will be used to perform these optimisations, and the results will be analysed through the Gaussview interface.

In performing an optimisation, both a method and a basis set are required. The method chosen impacts on the approximations made in solving the Schrodinger equation, and the basis set chosen affects the accuracy of calculations. Higher level basis sets will give more accurate results, but the calculations will take longer and use considerably more computational resources.

During an optimisation, both electron and nuclei properties are calculated. The electronic density of a molecule is solved using an SCF component, which involves assigning a fixed position to the B and H atoms, before solving the Schrodinger equation for the electron density and energy. The nuclear positions are calculated using the OPT component. This involves continually changing the nuclear geometry, and running the SCF calculation at each of these geometries, until the lowest energy geometry (the ‘optimised’ geometry) is found.

Several factors must be taken into account when analysing the results of the calculations. Errors on the energy are on the order of 10 kJ mol-1. Converting this to atomic units (hartree) gives an error of 0.00381 hartree. The accuracy of the dipole moment is around 2 decimal places, and the frequencies are only correct to within around 10%, due to the use of a harmonic approximation when the vibrations observed are actually anharmonic. Similarly, the calculated intensities are only accurate to within one integer, bond lengths to within 0.01Å and bond angles to 0.1o. All of these factors mean that the results obtained during these calculations cannot be taken to be definitive values.

These factors will be taken into account when interpreting the results from the optimisations below.

Analysis of BH3

Creating and optimising a molecule of BH3

A molecule of BH3 was created using Gaussview version 3.09, before adjusting the structure by increasing all the B-H bond angles to 1.5Å (whilst leaving the B centre in a fixed position). This geometry was then optimised using a B3LYP method, a 3-21G basis set and an OPT (optimisation) calculation. File:Hollybh3optimisedlogfile.txt

hollybh3optimisedjmol.mol |

The optimised structure has the following geometric information:

| B-H bond length (Å) | H-B-H bond angle (o) |

|---|---|

| 1.19435 | 120.000 |

No comparative B-H bond length in borane was found, though in diborane, B2H6, X-ray diffractions have found the B-H(terminal) bond length to be 1.09Å.[1]. This therefore suggests that the value obtained during this calculation is sensible.

The 120o angle obtained corresponds to an ideal trigonal planar geometry, meaning that all three hydrogens are in the same environment and are thus chemically identical.

Additional parameters from the results of the optimisation can be seen as follows:

To confirm the optimisation had been carried out successfully, the gradient of the output was analysed: this had a value of 0.00000285 hartree, which is less than the maximum allowed value of 0.001, meaning the optimisation was performed successfully.

To confirm that the results had converged as desired, the log file for the results was analysed. This showed the following forces and displacements:

This shows that all four forces and displacements have converged as required for further analysis.

In Gaussview, the log file from the above BH3 optimisation was opened, ensuring that the “Read intermediate geometries” box was ticked during the opening process. ‘Results’, followed by ‘optimisation’, were selected, to observe how the energy and gradient underwent changes during the optimisation. This can be seen in the following graphs:

Gaussview allows an animation of the molecular structure to be seen at different optimisation steps during the optimisation process.

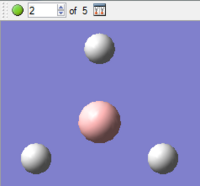

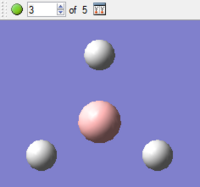

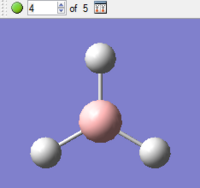

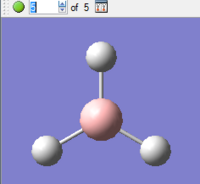

These changes in molecular structure can be seen as follows:

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

As can be seen in the first diagram, during the first optimisation step, there are no bonds shown between the boron centre and the surrounding hydrogen atoms. This is due not to the fact that the bonds are not present, but that Gaussview has a pre-defined distance for showing bonds on a structure and the bond length during the first optimisation step (presumably around 1.5Å, as this is what was initially inputted) is greater than this pre-defined distance.

The final structure, during optimisation step 5, has the lowest (most negative) energy. This therefore corresponds to the most stable structure found over the optimisation process, and corresponds to the ground state of the molecule. This structure is in fact the structure which would be found in the gas-phase of the molecule, when intermolecular interactions are at a minimum.

The molecular orbitals of BH3

The checkpoint file from the above BH3 optimisation was opened, before running an MO analysis using a “full NBO” and applying “pop=full” in the additional keywords section, to activate the MO analysis. As before, a B3LYP method and a 3-21G basis set were used. This file was submitted to Scan (http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6638), before the resulting molecular orbitals were opened from the checkpoint file.

This gave the following MOs:

| MO 1 | MO 2 | MO3 | MO 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| MO 5 | MO 6 | MO 7 | MO 8 |

|

|

|

|

The unoccupied orbitals, numbers 5 to 8, show a more diffuse character than their occupied counterparts, orbitals 1-4.

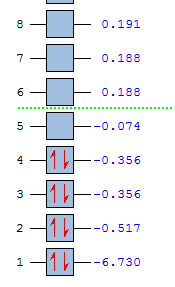

The quantitative MO energy levels calculated are as follows (the energies are expressed in atomic units):

This shows that there are two sets of doubly degenerate orbitals, which correspond to the 1e’ and the 2e’ levels.

Comparing the computed MOs with those of an MO diagram gives the following result:

This shows that the quantitative molecular orbitals calculated agree extremely well with those predicted using qualitative moleculaer orbital theory. The only real difference is that MO theory predicts that the 2e’ level lies above the 3a1’ level, whereas the quantitative energies provided by the calculations suggest that the 3a1’ level should in fact lie about the 2e’ level.

NB molecular orbital 1 is not shown on the above MO diagram; this corresponds to the filled 1s shell of boron, which is too low in energy to interest with the H 1s orbitals. Overall, qualitative MO theory is a useful aide in predicting the structures of compounds, but computational methods are required for more accurate results.

A Natural Bond Orbital analysis of BH3

To perform a Natural Bond Orbital analysis, the log file from the BH3 optimisation was opened, before viewing the charge distribution present within the structure. This gave the following pictorial representation, where green indicates a highly positive charge (as expected for the electropositive boron atom, which is strongly Lewis acidic), and red indicates a highly negative charge:

This result can also be shown quantitatively:

Opening the log file allows the NBO analysis to be investigated.

The “Summary of Natural Population Analysis” gives the following data:

Summary of Natural Population Analysis:

Natural Population

Natural -----------------------------------------------

Atom No Charge Core Valence Rydberg Total

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

B 1 0.33126 1.99904 2.66970 0.00000 4.66874

H 2 -0.11042 0.00000 1.11010 0.00032 1.11042

H 3 -0.11042 0.00000 1.11010 0.00032 1.11042

H 4 -0.11042 0.00000 1.11010 0.00032 1.11042

=======================================================================

* Total * 0.00000 1.99904 6.00000 0.00097 8.00000

The ‘natural charges’ from the table correspond to those shown on the image above.

The “Bond orbital/Coefficients/Hybrids” section is as follows:

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.99851) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2

( 44.49%) 0.6670* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.8165 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.51%) 0.7451* H 2 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

2. (1.99851) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3

( 44.49%) 0.6670* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.51%) 0.7451* H 3 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

3. (1.99851) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4

( 44.49%) 0.6670* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 -0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.51%) 0.7451* H 4 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

4. (1.99904) CR ( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

5. (0.00000) LP*( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

The second order perturbation theory analysis of Fock Matrix in NBO analysis data from the above calculation can be seen below:

Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis of Fock Matrix in NBO Basis

Threshold for printing: 0.50 kcal/mol

E(2) E(j)-E(i) F(i,j)

Donor NBO (i) Acceptor NBO (j) kcal/mol a.u. a.u.

===================================================================================================

within unit 1 4. CR ( 1) B 1 / 10. RY*( 1) H 2 1.51 7.55 0.095 4. CR ( 1) B 1 / 11. RY*( 1) H 3 1.51 7.55 0.095 4. CR ( 1) B 1 / 12. RY*( 1) H 4 1.51 7.55 0.095

The summary of the natural bond orbitals from the above calculation can be seen as follows:

Natural Bond Orbitals (Summary):

Principal Delocalizations

NBO Occupancy Energy (geminal,vicinal,remote)

====================================================================================

Molecular unit 1 (H3B)

1. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2 1.99851 -0.43697

2. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3 1.99851 -0.43697

3. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4 1.99851 -0.43697

4. CR ( 1) B 1 1.99904 -6.64515 10(v),11(v),12(v)

5. LP*( 1) B 1 0.00000 0.67699

Performing a vibrational analysis on BH3

A vibrational analysis was performed, to ensure that the optimised structure from earlier was indeed the optimised structure for the BH3 molecule. This involved opening the output file from the BH3 optimisation, with the “read intermediate geometries” box checked, before performing a Gaussian frequency calculation on the structure. In the additional keywords box, “pop=(full,nbo)” was added, to perform a full electron density and MO analysis.

Viewing the summary energy of the resulting file showed the same energy as that recorded for the optimisation.

In the output file, the following frequencies were detailed:

Low frequencies --- -0.6560 -0.0171 -0.0021 20.1987 21.4875 21.4975

Low frequencies --- 1145.7148 1204.6589 1204.6599

Diagonal vibrational polarizability:

0.6041804 0.6041102 1.9004460

Harmonic frequencies (cm**-1), IR intensities (KM/Mole), Raman scattering

activities (A**4/AMU), depolarization ratios for plane and unpolarized

incident light, reduced masses (AMU), force constants (mDyne/A),

and normal coordinates:

1 2 3

A" E' E'

Frequencies -- 1145.7148 1204.6589 1204.6599

Red. masses -- 1.2531 1.1085 1.1085

Frc consts -- 0.9691 0.9478 0.9478

IR Inten -- 92.6991 12.3789 12.3814

Atom AN X Y Z X Y Z X Y Z

1 5 0.00 0.00 0.16 0.00 0.10 0.00 -0.10 0.00 0.00

2 1 0.00 0.00 -0.57 0.00 0.08 0.00 0.81 0.00 0.00

3 1 0.00 0.00 -0.57 -0.38 -0.59 0.00 0.14 0.38 0.00

4 1 0.00 0.00 -0.57 0.38 -0.59 0.00 0.14 -0.38 0.00

4 5 6

A' E' E'

Frequencies -- 2592.7908 2731.3088 2731.3095

Red. masses -- 1.0078 1.1260 1.1260

Frc consts -- 3.9918 4.9491 4.9491

IR Inten -- 0.0000 103.8370 103.8302

Atom AN X Y Z X Y Z X Y Z

1 5 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.11 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.11 0.00

2 1 0.00 0.58 0.00 0.02 0.00 0.00 0.00 -0.81 0.00

3 1 0.50 -0.29 0.00 -0.60 0.36 0.00 0.36 -0.19 0.00

4 1 -0.50 -0.29 0.00 -0.60 -0.36 0.00 -0.36 -0.19 0.00

The ‘low frequencies’ lines detail the 6 vibrations which constitute the ‘-6’ portion of the 3N-6 vibrations of the BH3 molecule. These are attributed to motions related to the centre of the mass of the BH3 molecule.

Choosing to view results, then vibrations, of the previous file enables the vibrational modes of the molecule to be viewed.

In total, 6 vibrations were found, 2 of which were doubly degenerate. The vibrational frequencies and their modes of action are shown below: Choosing to display the vibrations resulted in animations of each of the six vibrations. These vibrations can be summarised as follows:

| Vibrational mode | Animation of vibration | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | Symmetry of vibration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

1146 | 93 | A2” | |||

| 2 |

|

1205 | 12 | E' | |||

| 3 |

|

1205 | 12 | E' | |||

| 4 |

|

2593 | 0 | A1' | |||

| 5 |

|

2731 | 104 | E' | |||

| 6 |

|

2731 | 104 | E' |

The IR spectrum from the above calculation can also be viewed. This can be seen as follows:

The spectrum displays only three peaks because two of the IR stretches are doubly degenerate, and another has an IR intensity of zero, meaning it is not seen on the spectrum.

No literature comparisons could be found for the vibrational frequencies of BH3. This is due to the fact that literature computational analyses of BH3 used different methods and basis sets, meaning that the values cannot be compared with those obtained above, using a different method and basis set. This is due to different approximations being used in the different methods and basis sets, which does not translate particularly well towards comparison.

Analysis of TlBr3

Creating and optimising a molecule of TlBr3

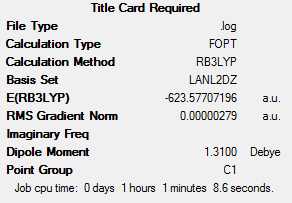

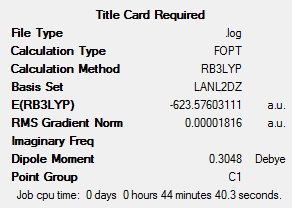

A molecular of TlBr3 was drawn on Gaussview 3.09, before restricting the point group to D3h with a ‘very tight’ tolerance. The geometry was optimised using the B3LYP method, and a LANL2DZ basis set. This is a medium-level basis set, as opposed to the lower level 3-21G basis set used in the above BH3 optimisation, meaning a higher level of accuracy should be seen for the heavier Tl element.

File:Hollytlbr3optimisation.txt

hollytlbr3optimisedjmol.mol |

The optimised Tl-Br distance was found to be 2.65095Å, and the optimised Br-Tl-Br bond angle was found to be 120o.

This compares to an experimental bond length of 2.512Å.[2] The two values are in reasonably good agreement, though one reason for the shorter literature value may be that it was proposed that two water molecules were bound to the TlBr3 compound, which would affect the bond lengths within the compound. One way of potentially improving the correlation between the two bond lengths is to use a better basis set, though this would require much longer computational times to compute.

A summary of the calculation results can be seen below:

Performing a vibrational analysis on TlBr3

To confirm this optimised structure is at an energy minimum, a frequency analysis was performed on the structure as for BH3. The same method and basis set were used for both the optimisation and frequency analysis, as this enables a valid comparison to be drawn between the two.

The first ‘low frequencies’ line corresponds to vibrational modes which are not classed as ‘real’ modes. The second ‘low frequencies’ line corresponds to the first three vibrational modes which are classed as ‘real’ modes.

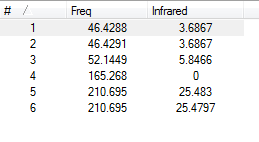

The six ‘real’ modes obtained for TlBr3 using this optimisation can be seen as follows:

Two of the modes appear to be doubly degenerate. The higher frequency of these pairs appears as a single absorption on the spectrum below, whereas the lowest frequency doubly degenerate pair overlaps with the absorption at 52.1 cm-1, producing a broad absorption peak. The animated frequencies can be seen as follows:

| Vibrational mode | Animation of vibration | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | Symmetry of vibration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

46 | 4 | E’ | |||

| 2 |

|

46 | 4 | E' | |||

| 3 |

|

52 | 6 | A2” | |||

| 4 |

|

165 | 0 | A1' | |||

| 5 |

|

211 | 25 | E' | |||

| 6 |

|

211 | 25 | E' |

The values obtained above for the vibrational frequencies agree well with literature Tl-Br vibrational frequencies found within a TlBr3.2py adduct: these are 211, 204, 190, 156, 137, 100 and 82 cm-1.[3]

The IR spectrum generated for this compound can be seen as follows:

Analysis of the cis- and trans- isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Creating and optimising the cis- and trans- isomers

The cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 were created and optimised, using the B3LYP method and an LANL2MB basis set, with keywords ”opt=loose” (to increase the calculation speed) to obtain a rough geometry for the two isomers.

| Cis isomer | Trans isomer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LANL2MB logfile | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6610 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6609 | ||||||

| Jmol of LANL2MB optimised structure |

|

|

The resulting optimised structures returned with no visible P-Cl bonds. This is due to the fact that the bond lengths are longer than those recognised by Gaussview, meaning they are not displayed. This low-level optimised structure was then optimised again using the B3LYP method and a different, LANL2DZ basis set. Additional keywords used for this optimisation were “int=ultrafine scf=cover=9”.

In order to perform the optimisation, the ‘missing’ P-Cl bonds had to be reinserted by using the bond length tool, selecting a P and a Cl atom, and selecting a single bond, rather than the ‘none’ which the program was set to. The torsion angles of the LANL2MB optimised cis and trans isomers were also altered:

In the cis conformer, the angles were altered so that one Cl atom pointed upwards, and parallel to the axial bond, whereas the other Cl pointed downwards, again parallel to the axial bond.

In the trans conformer, it was ensured that both of the PCl3 groups were eclipsed, and that one of the P-Cl bonds lay parallel to an Mo-C bond.

The LANL2DZ optimisation was then performed, to give the following optimised summaries:

This shows that the relative energies of the two isomers are very similar, but that the cis isomer is in fact more stable by 0.000104 hartree (2.73 kJ mol-1). This energy difference is very small, suggesting that intramolecular geometrical isomerism should be possible at room temperature. This result is somewhat surprising – it may have been expected that the trans isomer, with the smaller dipole moment, would be the more stable of the two. Experimental findings have concluded that cis Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2, a related compound, is more stable than the trans form. The CO and Cl ligands resemble each other in size, meaning that this finding may be applied to the compounds analysed in this case.[4]

In general, for Mo(CO)4(PR3)2 species, the relative stability of the cis and trans isomers appears to vary depending on the nature of the phosphine ligand. When R = Ph, it has been found that phosphine dissociation is more likely to occur from the cis form than the trans form, suggesting the trans form is more stable. In fact, the stability of the trans form has been found to have a of hange in Gibb's free energy of -1 kcal compared to the cis form. This is probably because steric interactions between the extremely sterically demanding PPh3 ligands are minimised in the trans form.

When R is a slightly smaller group, however, e.g. R = Me2Ph or R = MePh2, the cis forms have shown no tendency to isomerise to the trans form.[5] This suggests that the energy gained from minimising steric interactions is less than the energy required for the dissociation and subsequent reassociation mechanism.

| Cis isomer | Trans isomer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LANL2DZ logfile | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6611 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6608 | ||||||

| Jmol of LANL2DZ optimised structure |

|

|

| Geometric parameter | Cis isomer | Literature value | Trans isomer | Literature value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-P bond length (Å) | 2.51 | 2.58 | 2.44 | 2.50 |

| Mo-C bond length (Å) | 2.06 | 2.06 | 2.06 | 2.00 |

| P-Cl bond length (Å) | 2.24 | 2.24 | ||

| C=O bond length (Å) | 1.17 | 1.15 | 1.17 | 1.16 |

| P-Mo-P angle (o) | 94.2 | 104.6 | 177.4 | 180.0 |

| C-Mo-C (cis) angle (o) | 89.7 | 87.0 | 90.5 | 92.1 |

| C-Mo-P (cis) angle (o) | 91.9 | 90.3 | 88.7 | 87.2 |

| C-Mo-C (trans) angle (o) | 178.4 | 174.1 | 180.0 | 180.0 |

| Cl-P-Cl angle (o) | 100.2 | 99.1 | ||

| C-Mo-P (trans) angle (o) | 176.1 | 173.2 | ||

| Cl-P-Mo angle (o) | 120.4 | 117.3 | ||

| O=C-Mo angle (o) (with CO group trans to ligand) | 177.9 | 176.6 | 180.0 |

NB the literature comparison[6] for the cis isomer relates to cis Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2, meaning that slight variations are to be expected.

The literature comparison for the trans isomer relates to trans Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2[7].

Performing a vibrational analysis on the cis- and trans- isomers

In order to confirm an optimised geometry had been obtained, a frequency analysis was performed on these optimised geometries. The additional keywords “int=ultrafine scf=conver=9” were retained.

| Cis isomer | Trans isomer |

|---|---|

| http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6613 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-6612 |

No negative frequencies were obtained, indicating that a true vibrational minima had been obtained. The ‘low’ frequency vibrational modes for the complexes are detailed below. It is likely that these vibrations will be occurring at room temperature, due to the very low energy input required to induce the vibrations.

| Vibrational mode | Animation of vibration (cis isomer) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | Vibrational mode | Animation of vibration (trans isomer) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

11 | 0 | 1 |

|

5 | 0 | ||||||

| 2 |

|

18 | 0 | 2 |

|

6 | 0 |

The vibrational frequencies associated with the C=O stretches are shown below.

| Vibrational mode | Animation of vibration (cis isomer) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | Vibrational mode | Animation of vibration (trans isomer) | Vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Vibrational intensity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 |

|

1945 | 763 | 42 |

|

1950 | 1475 | ||||||

| 43 |

|

1949 | 1498 | 43 |

|

1951 | 1467 | ||||||

| 44 |

|

1958 | 633 | 44 |

|

1977 | 1 | ||||||

| 45 |

|

2023 | 598 | 45 |

|

2031 | 4 |

In transition metal carbonyl complexes, the number of vibrational bands for CO is linked to the symmetry of a complex. The number of absorptions can be determined by looking at a molecule’s point group:

Cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 isomer: Linear? No -->

2 or more Cn, n>2? No -->

Cn? Yes C2 -->

2C2 perpendicular to C2? No -->

σh? No -->

2σv? Yes --> C2v

Trans isomer:

Linear? No --> 2 or more Cn, n>2? No --> Cn? Yes C4 --> 4C2 perpendicular to C4? Yes --> σh? Yes --> D4h

It has been found for cis-octahedral metal complexes that 4 infrared absorption bands will be exhibited[8] – one medium intensity band at a higher frequency, along with three intense, closely spaced bands at a slightly lower frequency. This can be rationalised by grouping the carbonyl ligands into two sets of two – one pair being cis to each other, the other trans. Four sets of carbonyl stretches are then possible – a symmetric, and asymmetric stretch of the trans CO’s, and a symmetric, and asymmetric stretch of the cis CO’s. These are assigned, respectively, as having A1a, B1, A1b and B2 symmetry (these labels relate to the C2v point group of the molecule).

These different stretches give rise to the four calculated peaks. The highest frequency peak is due to symmetric stretching of the two trans carbonyls – trans carbonyls have stronger force constants and thus a higher frequency, and also symmetric stretches have higher frequencies. On this basis, the highest frequency is due to A1a symmetry, the second highest A1b, the third highest B1 and the lowest B2.

During second year synthesis labs, for cis-[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] on my spectrum the absorption bands were at 2024, 1924, 1895 and 1869 cm-1. The literature[9] gives the absorptions at 2023, 1927, 1908 and 1897 cm-1. These values agree reasonably well with those calculated for the cis isomer of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 shown below. Differences may arise due to PCl3 ligands being used for the calculations (which require lower computational power), as opposed to the PPh3 ligands used in both the actual experiment and that from the literature comparison.

A trans-tetracarbonyl complex is only expected to exhibit one carbonyl absorption as all the carbonyls are in the same environment.[10] The literature value of the carbonyl absorption in trans-[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] is 1901 cm-1.

This contradicts the computational finding, shown below, which predicts that 4 peaks will be shown in the IR spectrum (admittedly two of these have a very low intensity, and may not correspond to ‘real’ vibrational modes). This discrepancy may arise because these points groups have been determined assuming a perfect octahedral geometry, with all bond angles of 90o, whereas in fact, as shown above, none of the bond angles have an ideal value of 90o.

Therefore the ideal geometry point group differs from that of the molecule when ligand interactions are taken into account.

Overall, the above calculations have shown that computational calculations can offer a reasonable fit to observed bond lengths and vibrational modes. To improve the fit, better basis sets and methods could be used, though these would require longer computational times and more computational power.

References

- ↑ D. S. Jones and W. N. Lipscomb, Acta Cryst., 1970, A26, 196.

- ↑ J. Glaser and J. Johansson, Acta. Chem. Scand., 1982, A36, 125.

- ↑ R. A. Walton, J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem., 1970, 32, 2875.

- ↑ D. W. Bennett et al, J. Chem. Cryst., 2004, 34, 353.

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg et al, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 294.

- ↑ F. A. Cotton et al, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 294.

- ↑ G. Hogarth and T. Norman, Inorg. Chim. Acta., 1997, 254, 167.

- ↑ A. D. Allen, P. F. Barrett, Can. J. Chem., 1968,46, 1649.

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, L. Kemp, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680.

- ↑ M. Y. Darensbourg, D. J. Darensbourg, J. Chem. Ed, 1970, 47, 33.