Rep:Mod:ht309mod1

3rd Year Computational Labs: Hideki Tanimura

The Hydrogenation of Cylopentadiene Dimer

The dimerisation of cyclopentadiene forms two isomers in the exo form (Compound 1) and the endo form (Compound 2). Further hydrogenation of the endo dimer produces Compounds 3 and 4.

Mechanism:

The dimerisation proceeds via a [4πs + 2πs] Diels-Alder cycloaddition.

Further hydrogenation of the endo dimer (2) forms the hydrogenated endo dimers (3) and (4).

Results:

The following geometries and energy values were determined using the MM2 force field option using ChemBio3D.

| Compound 1 (-exo dimer) | Compound 2 (-endo dimer) | Compound 3 | Compound 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Relative Contributions | Compound 1 (-exo dimer) /kcalmol-1 | Compound 2 (-endo dimer) /kcalmol-1 | Compound 3 /kcalmol-1 | Compound 4 /kcalmol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.29 | 1.25 | 1.23 | 1.10 |

| Bend | 20.58 | 20.85 | 18.94 | 14.52 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.84 | -0.84 | -0.76 | -0.55 |

| Torsion | 7.65 | 9.51 | 12.12 | 12.50 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.42 | -1.54 | -1.50 | -1.07 |

| 1,4 VDW | 4.23 | 4.32 | 5.73 | 4.51 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.14 |

| Total Energy | 31.88 | 34.00 | 35.93 | 31.15 |

Analysis:

Dimerisation

The exo dimer (1) was found to be lower in energy by 2.12 kcalmol-1 (9.25kJmol-1) compared to the endo dimer (2). Thus the exo form is more thermodynamically stable and in theory should be the predominant product if the reaction was under thermodynamic control. However Diels-Alder cycloaddition is under kinetic control - the endo form is always preferred[1].

The transition states for the dimerisation can be used to explain why the endo form is the predominant species in the reaction. The secondary orbital interactions between the HOMO and LUMO pz orbitals allow for greater overlap and thus greater stabilization of the transition state. Greater stabilization of the transition state leads to a lower activation energy and thus the endo form is preferred under kinetic control. Below we can see that the endo approach would proceed via a more stable transition state.

Hydrogenation

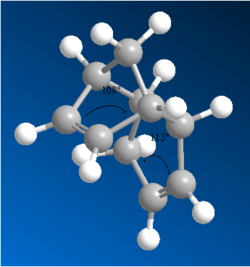

Compound (4) was found to be more thermodynamically stable than compound (3) (4.78kcalmol-1). The main contributor to this energy difference was the bending energy (4.42 kcalmol-1). The hydrogenation of Compound (2) changes the conformation via the hybridized orbitals of the carbon atoms. The bond angle of C=C-C in the norbornene is 108o and in the five membered ring is 113o. This means that the C-C bond in the norbornene is more likely to be hydrogenated as it would reduce the angular strain (ideal C-C sp2 bond angle is 120o but sp3 is 109.5o). This is why compound (3) was less stable as the ring strain in the norbornene still exists.

It was also observed that compound (4) was more stable than compound(2), it's precursor (31.15 and 34.00 kcalmol-1). This showed that the hydrogenation of compound (2) to compound (4) was preferred under thermodynamic control as explained above.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

A key intermediate 9 or 10 in the total synthesis of Taxol proposed by Paquette is initially synthesised with the carbonyl group pointing either up or down. They are formed from an oxy-Cope rearrangemen[2] and are atropisomers arising from high steric demand. On standing the intermediates isomerise to the alternative carbonyl isomer.

Results:

The following geometries and energies were obtained using MM2 molecular mechanics. It was observed that the conformations were of lowest energy when the cyclohexane was in a chair conformation (rather than a twist-boat).

| Taxol Intermediate (9) | Taxol Intermediate (10) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| Relative Contributions | Taxol Intermediate (9) "down" /kcalmol-1 | Taxol Intermediate (10) "down" /kcalmol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.79 | 2.62 |

| Bend | 16.54 | 11.34 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.43 | 0.34 |

| Torsion | 18.24 | 19.66 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.55 | -2.16 |

| 1,4 VDW | 13.11 | 12.87 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.72 | -2.00 |

| Total Energy | 47.84 | 42.68 |

The geometries/energies were then optimized further using MMFF94.

| Molecule | Allinger MM2 Energy Minimization /kcalmol-1 | MMFF94 Energy Minimization /kcalmol-1 | Geometry [MMFF94]] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxol Intermediate (9) | 47.84 | 70.54 | |

| Taxol Intermediate (10) | 42.68 | 60.60 |

Analysis:

It could be concluded from both MM2 and MMFF94 minimizations that Taxol Intermediate (10), the "down" isomer, was more thermodynamically stable (42.68 < 47.84 kcalmol-1 and 60.60 < 70.54 kcalmol-1 respectively). The Allinger MM2 derived lower estimates for the optimised energy stability than the MMFF94. This was due to the different parameters and approaches the two methods use.

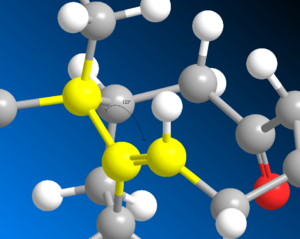

This stability can be explained in terms of molecular orbitals; there is overlap between σ(C-H) and π*(C=O) when the carbonyl group points "down" but not "up".

It was also useful to investigate the hyperstable alkene group[3]. It is hyperstable because although it appears to be in a strained conformation it is under less torsional strain than expected. In fact, the saturated derivative of the molecule would be under more torsional strain. This could be demonstrated by comparing Taxol Intermediate (10) with its saturated derivative.

The following was determined using MOPAC/PM6:

| Taxol Intermediate (10) | Energy [MOPAC/PM6] /kcalmol-1 | Angle of torsion at bridgehead /o |

|---|---|---|

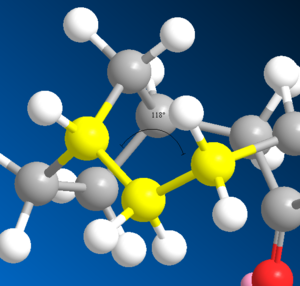

| Unsaturated | 60.60 |  123 123

|

| Saturated | 69.55 |  118 118

|

The saturated derivative was found to be more thermodynamically unstable. The angle for the unsaturated taxol intermediate (10) was 123o. This is fairly close to it's theoretical angle (for an sp2 hybridised C=C-C angle) of 120o. However the angle for the saturated derivative was found to be 118o. The theoretical angle for an sp3 hybridised C-C-C angle is 109.5o. Thus the saturated derivative would be under large steric strain.

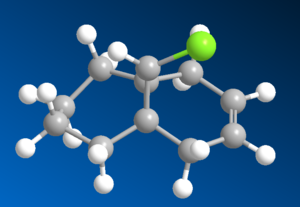

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

The regioselectivity of an enophilic attack to compound (12) (see right) was investigated in this section. The reaction would be a [1+2] cycloaddition of the following mechanism (using dichlorocarbene as the enophile/electrophile).

Results:

The following molecular orbitals were obtained using the MOPAC/PM6 method.

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Analysis:

The HOMO showed large electron density on the π bonding orbital on the C=C alkene endo or syn to the C-Cl bond; most susceptible to electrophilic attack. The LUMO showed that the alkene group exo or anti to the C-Cl bond had a large π* anti-bonding obital; most susceptible to nucleophilic attack. The HOMO-1 showed large electron density on the π bonding orbital anti to the C-Cl. The LUMO+1 showed the σ* anti-bonding orbital of C-Cl was capable of orbital overlap with the π bonding orbital anti to C-Cl. The πc-c would thus interact with the σ*C-Cl meaning nucleophilic attack would occur on the π orbital exo to C-Cl. This is where the regioselectivity arises.

The dialkene had a cs symmetry going down the plane of the C-Cl bond perpendicular to the plane of the ring. This was verified by the shapes of the FMOs.

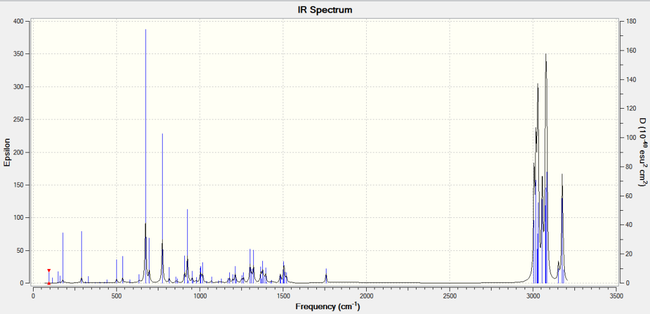

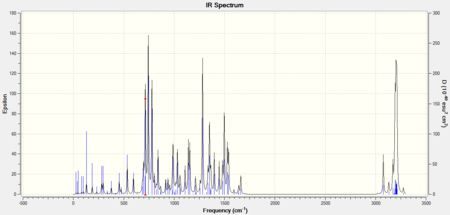

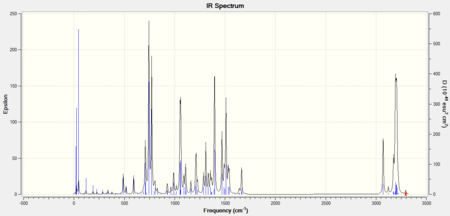

Vibrational Spectra:

| Compound 12 | Mono hydrated product |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Stretches | Diene Wavenumer /cm-1 | Diene Animation | Monoalkene Wavenumer /cm-1 | Monoalkene Animation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-Cl | 770.86 |  |

775.00 |

|

| anti/exo C=C | 1737.03 |  |

n/a | n/a |

| syn/endo C=C | 1757.34 |  |

1757.07 |

|

The vibrational spectra were predicted via DFT. The peaks (see above) showed that the peak ~1737 cm-1 came from anti/exo C=C stretching as the peak appeared on the diene spectrum but not the monoalkene one.

Monosaccharide chemistry: glycosidation

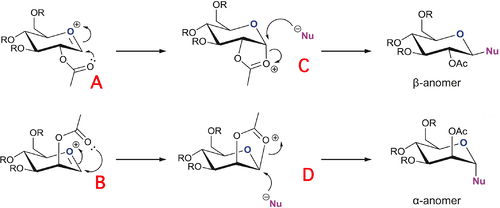

Glycosidation involves the nucleophilic substitution of the group X by a nucleophile Nu. Below is a reaction scheme for such a nucleophilic substitution.

The two monosaccharides A and B, due to the orientation of the OAc group attached to the adjacent carbon produce different anomers, as seen in the reaction scheme, via specific stereoselective steps. This is due to neighbouring-group-participation from the OAc group (see C and D). For the β anomer, i.e. the nucleophile attaches onto the equatorial position, to be synthesised, the oxonium cation in the ring must be attacked from below the plane of the ring. This allows for the nucleophile to attack from the top. For the α anomer, i.e. the nucleophile attaches onto the axial position, the oxonium cation must be attacked from above the plane of the ring, thus allowing the nucleophile to attack from the bottom.

For the reaction scheme above, R = Me was used to minimise error and the processing time in the modelling.

Results:

The following geometries and energies were predicted using the Allinger MM2 model first. However, it was observed that the model was not ideal due to the fact it does not consider effects from neighbouring-group-participation.. Thus a new mdoel the MOPAC/PM6 was used to determine the geometries of A, A', B, B', C, C', D, D' where the " ' " indicates that the acetyl group points above the plane of the 6-membered ring (where the oxonium cation lies).

| Monosaccharide | Geometry [MOPAC/PM6] | Stretch /kcalmol-1 | Bend /kcalmol-1 | Stretch-Bend /kcalmol-1 | Torsion /kcalmol-1 | Non-1,4 VdW /kcalmol-1 | 1,4 VdW /kcalmol-1 | Charge/Dipole /kcalmol-1 | Dipole/Dipole /kcalmol-1 | Total Energy /kcalmol-1 [MM2] | Energy /kcalmol-1 [MOPAC/PM6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.82 | 11.89 | 1.08 | 3.14 | 1.46 | 18.96 | -25.57 | 5.91 | 19.68 | -91.65 | |

| A' | 2.46 | 11.31 | 0.96 | 2.28 | -2.35 | 18.71 | -6.69 | 4.16 | 30.84 | -77.40 | |

| B | 2.73 | 10.71 | 0.98 | 2.80 | 0.63 | 18.93 | -21.80 | 5.53 | 20.56 | -88.73 | |

| B' | 2.51 | 9.85 | 0.90 | 2.65 | -1.51 | 19.22 | -9.47 | 3.85 | 28.00 | -77.51 | |

| C | 2.06 | 13.73 | 0.74 | 9.66 | -2.66 | 17.89 | -9.92 | -2.23 | 29.26 | -91.65 | |

| C' | 2.69 | 20.04 | 0.86 | 8.45 | -2.82 | 18.61 | -2.70 | -1.40 | 43.73 | -67.00 | |

| D | 1.93 | 17.12 | 0.76 | 8.59 | -2.29 | 17.31 | -11.64 | -1.58 | 30.21 | -91.64 | |

| D' | 2.90 | 18.28 | 0.90 | 9.29 | -2.05 | 19.07 | 1.79 | -1.54 | 48.63 | -66.84 |

It could be observed from the energy data that the "plain" geometry (where the acetyl group points below the plane of the ring) was more stable than the dashed, " ' ", geometry (where the acetyl group points above the plane of the ring).

The main contributor to this difference in stability was the energy (or stability) arising from charge/dipole interactions.

Looking back on the geometries, A and B have the acetyl group nearly directly above, or below the oxonium cation. It was believed the geometries were stabilized by interactions between them(in fact the simple MM2 model favoured these forms)

Certainly the main contributions for the charge/dipole interactions would have arisen from the oxonium cation and the acetyl group. Observing that "plain" geometries were more thermodynamically stable, the angle and the distance between the oxonium cation and the acettyl group were tabulated.

| Molecule | Angle between the two oxygen atoms /o | Distance between the two oxygen atoms /nm |

|---|---|---|

| A | 41.6 | 0.233 |

| A' | 13.1 | 0.398 |

| B | 41.0 | 0.235 |

| B' | 15.5 | 0.394 |

The data above showed that the molecules were more thermodynamically stable when the oxygen on the acetyl group was close to the oxonium cation (~0.234 nm) at a steep angle of ~41o. Diastereospecificity could be concluded from these data as the close distance/steep angle suggests more stability in their intermediates C and D. This would drive a high stereochemical selection although it is still common to obtain mixtures of the stereoisomers[4].

Structure based Mini project using DFT-based Molecular orbital methods

Assigning regioisomers in "Click Chemistry"

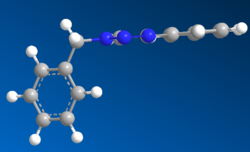

Click chemistry was introduced by Sharpless in 2001 and describes chemistry that is modelled to generate molecules quickly and reliably by joining small modular units together. The most powerful click reaction to date[5] is the Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC)[6]. The reaction is regioselective depending on the catalyst used. When mono-substituted alkynes and azides are used, they react via 1,3 polar cycloaddition to form two possible regioisomeric di-substituted 1,2,3-triazoles. Interestingly under Ru(II) catalysis the 1,5-isomer A forms but when Cu(I) is used the 1,4-isomer B forms.

In this investigation molecular modelling was used to determine whether the isomers could be differentiated using spectroscopic methods.

Mechanism:

For this investigation, R1 = Ph, R2 = -CH2Ph were chosen.

Results

Geometry

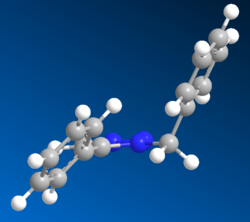

Using MM2 and MOPAC/AM1 the following geometries were obtained:

| Product (A)/MM2 | Product (A)/MOPAC/AM1 | Product (B)/MM2 | Product (B)/MOPAC/AM1 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

A

The simple Allinger MM2 modelling produced very planar benzene-triazole rings with a bend at the bridging carbon atom. The 5-substituted benzene ring was completely in plane with the triazole and the 1-substituted benzene was bent around the bridging carbon by an angle of 112.9o. This was certainly greater than the theoretical sp3 bend of 109.5o suggesting repulsion between the two ring structures most likely to be due to their delocalised nature. The distance between the benzene rings in terms of two closest hydrogen atoms was 0.269nm. The slightly more complex MOPAC/AM1 method generated a fairly different conformation. Both benzene rings were out of plane with the triazole but nearly in parallel with each other. The bend at the bridging carbon was now at 114.9o, suggesting more repulsion. The distance between the benzene rings in terms of two closest hydrogen atoms was 0.246nm.

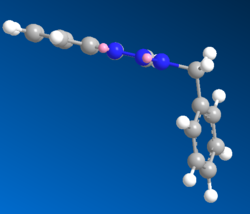

B

The Allinger MM2 produced a conformation where the two benzene rings planes were completely perpendicular to each other and the 4-substituted benzene was completely in plane with the triazole. The bend at the bridging carbon was 109.8o, somewhat lower, and much less strained than that found for A. The benezene rings were apart by a distance of 0.477nm. This suggested that the isomer B was much more stable than A. The MOPAC/AM1 produced a similar structure however the 4-substituted benzene was no longer in plane with the triazole ring. The angle of the bend was now 114.3o, suggesting more repulsion between the two rings. This was also verified by a longer distance of 0.561nm between the two benzene rings.

The stability of the two isomers were then computed using Allinger MM2.

Energy Optimisation

| Isomer | Stretch kcalmol-1 | Bend kcalmol-1 | Stretch-Bend kcalmol-1 | Torsion kcalmol-1 | Non-1,4 VdW kcalmol-1 | 1,4 VdW kcalmol-1 | Dipole/Dipole kcalmol-1 | Total Energy kcalmol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.11 | 18.30 | 0.11 | -15.72 | 0.73 | 14.37 | -1.66 | 17.22 |

| B | 0.77 | 13.11 | -0.03 | -14.83 | -1.68 | 14.72 | -1.41 | 10.65 |

MM2 predicted that isomer B is very much more stable; this was what was expected from the analysis of the structures.

DFT Calculations

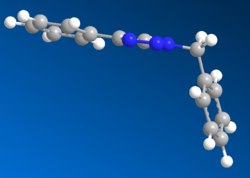

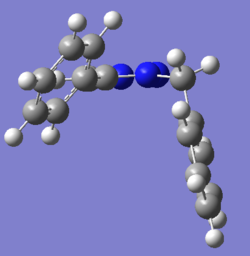

The geometries were recalculated using Gaussian mpw1pw91/6-31g(d,p):

| Product (A) Gaussian | Product (B) Gaussian |

|---|---|

|

|

A

The DFT model computed a similar structure to the MOPAC/PM6 but the benzene rings were not parallel with each other. The bend at the bridging carbon was now 112.9o which was in between values given by MM2 and MOPAC/PM6. Interestingly the distance between the two rings was now 0.377nm and the 4-substituted benzene was more out of plane with the troazole ring.

B

The DFT calculated complete delocalisation above and below the 4-substituted benzene and the triazole rings. Again the 1-substituted benzene was perpendicular to the plane of trizole but the DFT predicted a a more slanted structure where the 1-substituted benzene points away. The bend about the bridging carbon was predicted 113.1o, again less than the MOPAC/PM6 prediction, and the distance between the two benzene rings was calculated at 0.578nm.

Spectra

NMR

The following NMR spectra were predicted using DFT/MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) using Gaussian on SCAN.

13C NMR

The following were predicted using the GIAO appraoch.

| Product | Conformation | NMR Full | NMR 13C | NMR 1H | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A |  |

|

|

|

DOI:10042/to-9526 |

| B |  |

|

|

|

DOI:10042/to-9522 |

| Gaussian Calculated | Literature[7] | Integral | Assignment | Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52.67 | 51.85 | 1 | Carbon 1 | +0.82 |

| 124.16 | 126.93 | 1 | Carbon 2 | -2.77 |

| 124.51 | 127.22 | 1 | Carbon 3 | -2.71 |

| 124.67, 124.79 | 128.22 | 2 | Carbon 4, 5 | -3.55 |

| 124.92, 125.23 | 128.92 | 2 | Carbon 6, 7 | -4.00 |

| 125.41, 125.54 | 129.08 | 3 | Carbon 8, 9, 10 | -3.67 |

| 125.87 | 129.64 | 1 | Carbon 11 | -3.77 |

| 126.53 | 133.26 | 1 | Carbon 12 | -6.73 |

| 130.14 | 133.34 | 1 | Carbon 13 | -3.20 |

| 131.78 | 135.66 | 1 | Carbon 14 | -3.88 |

| 136.00 | 138.26 | 1 | Carbon 15 | -2.26 |

The NMR data obtained from the GIAO approach seemed to be fairly accurate. The biggest error in the chemical shift was 6.73 ppm of C12. This could have been due to the slant between the triazole and the 4-substituted benzene ring. Since the 1-substituted benzene is completely above the plane of triazole, as is C12, C12 would be affected the most from shielding; in fact the 1-substituted benzene points in the direction of C12. Otherwise the average error was 2.49 ppm. The error in the predicted chemical shifts was not consistent and was not affected by the size of the chemical shift, i.e. the error did not increase proportionally. This meant that the error in the data did not come directly from the GIAO approach but from the wrong geometry.

| Gaussian Calculated | Literature (only the spectrum was provided) | Integral | Assignment | Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54.91 | 54.0 | 1 | Carbon 1 | +0.91 |

| 116.19 | 120.0 | 1 | Carbon 2 | -3.81 |

| 121.10, 122.33, 123.95 | 126.0 | 3 | Carbon 3, 4, 5 | -4.90 |

| 124.20 | 128.0 | 1 | Carbon 6 | -3.80 |

| 124.43 | 128.5 | 1 | Carbon 7 | -4.07 |

| 124.65 | 129.0 | 2 | Carbon 8, 9 | -4.35 |

| 124.77, 125.23 | 129.0' | 2 | Carbon 10, 11 | -4.23 |

| 125.67 | 129.5 | 1 | Carbon 12 | -3.93 |

| 127.86 | 131.0 | 1 | Carbon 13 | -3.14 |

| 133.14 | 135.0 | 1 | Carbon 14 | -1.86 |

| 145.02 | 148.5 | 1 | Carbon 15 | -3.48 |

The biggest error here was 4.90 ppm for C3. Similar to C12 of isomer A, the carbon atom is slightly above the triazole plane due to a slant between the 4-substituted benzene and triazole. However due to the delocalised nature (as predicted by DFT modelling) of 4-substituted benzene and triazole it is less affected by shielding from the 1-substituted benzene. The shielding is reduced further by the larger bend around the bridging carbon atom. The average error was 2.57 ppm. Had there been a set of tabulated 13C peaks to support the spectrum given in the literature a more accurate value for the error would have been obtained.

The average errors obtained from the two 13C NMR spectra were consistent ~2.53 ppm. This is the error in the GIAO approach for modelling 13C NMR of disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles where the groups attached are benzyl and phenyl and the solvent used is CDCl3.

3J H-H

The following 3H J-J coupling constants were predicted using Janocchio.

| Hydrogen Couple | Coupling Constant /Hz | Dihedral Angle /o |

|---|---|---|

| 1-substituted benzene | ||

| 1-2 | 8.2195 | 0.4 |

| 2-3 | 8.2200 | 0.0 |

| 3-4 | 8.2199 | -0.2 |

| 4-5 | 8.2197 | -0.4 |

| 5-substituted benzene | ||

| 6-7 | 8.2130 | -1.7 |

| 7-8 | 8.2189 | -0.7 |

| 8-9 | 8.2199 | -0.2 |

| 9-10 | 8.2187 | -0.7 |

The vicinal coupling constants for the 1-substituted benzene were of similar value (8.20 Hz) as expected as all hydrogen atoms can be assumed to be in the same environment due to the near-planar nature of the benzene ring and the triazole. However the 5-substituted benzene gave different coupling constants. The two hydrogen atoms (H6 and H10) closest to the triazole gave slightly lower coupling constants with its neighbouring hydrogen. This is due to the torsion in the benzene ring. The dihedral angle between H6 and H7 is great (1.7o) compared to the rest of the vicinal hydrogen atoms (this can be verified using the Karplus equation). The delocalization on the triazole distorts the conformation of the hydrogen atoms making the benzene ring slightly non-planar. Clearly, due to the extra carbon atom in between the benzene ring and the triazole the 1-substituted benzene is not affected as much as the 5-substituted one.

| Hydrogen Couple | Coupling Constant /Hz | Dihedral Angle /o |

|---|---|---|

| 1-substituted benzene | ||

| 1-2 | 8.2199 | -0.1 |

| 2-3 | 8.2200 | 0.1 |

| 3-4 | 8.2200 | 0.1 |

| 4-5 | 8.2200 | -0.1 |

| 5-substituted benzene | ||

| 6-7 | 8.2200 | -0.1 |

| 7-8 | 8.2200 | -0.0 |

| 8-9 | 8.2200 | 0.0 |

| 9-10 | 8.2200 | 0.0 |

The vicinal coupling constants for isomer B were all consistent (8.2200 Hz). This was due to the fact that the 4-substituted benzene ring was directly in plane with triazole; hence no distortion of the ring and thus constant dihedral angles. The 1-substituted also gave constant vicinal coupling. The bend around the bridging carbon was computed ealier using DFT modelling as 112.9o and 113.1o (for A and B respectively). Therefore in B, unlike A, there were also no minuscule distortions in the two hydrogen atoms closest to the triazole (H1 and H5).

IR Spectra

| Stretch/Bend Type | Wavenumber (Isomer A) cm-1 DOI:10042/to-9540 | Wavenumber (Isomer B) cm-1 DOI:10042/to-9539 |

|---|---|---|

| C-H Stretch (Triazole) | 3275.89 | 3295.37 |

| C-H Stretches (Phenyl Arene) | 3214.49, 3209.10, 3201.22 | 3209.54, 3199.56, 3190.88 |

| C-H Stretches (Benzyl Arene) | 3210.66, 3203.75, 3193.74 | 3204.87, 3193.23, 3183.67 |

| CH2 Stretch | 3130.80 | 3122.23 |

| C=C Stretch (Benzyl Arene) | 1662.51 | 1665.86 |

| C=C Stretch (Phenyl Arene) | 1662.04 | 1663.48 |

| N-N Stretch (Triazole) | 1282.42 | 1309.32 |

| C-H Bend (Benzyl Arene) | 779.66 | 771.48 |

| C-H Bend (Phenyl Arene) | 743.47 | 744.03 |

The IR spectra showed that for most stretch peaks isomer A had a higher wavenumber than that for isomer B. The main exceptions seemed to be the C-H stretch peak found on the triazole, the C=C stretch peaks for arenes, and the N-N peak for the N-N=N on the triazole. This demonstrated a good differentiator for future investigations on disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole molecules; by studying the triazole parts of the vibrational spectrum. The values for the peaks were slightly out of range compared to the literature but that was thought to be due to the delocalised systems on the molecules.

Other Tests & Conclusion

There was no point investigating the two isomers by predicting the Optical Rotation as both isomers have no chiral centres. Predicting the Electronic Circular Dichroism could have been useful however, the NMR and the IR spectra proved to be good enough indicators to differentiate between the two isomers.

The free energies of the isomers were predicted using DFT. Isomer A gave a ΔG value of -743.46 kJmol-1 and isomer B gave a ΔG value of -743.47 kJmol-1. The test proved useless for the differentiation of the two isomers.

Many different spectroscopic methods were computed/predicted using DFT. It was conclusive that the NMR estimation was fairly accurate with the literature (error of ~2.57 ppm) and the IR calculations were efficient in differentiating between the two isomers. Given more time it would have been useful to have repeated the same spectroscopic methods on different substituents (i.e. different functional groups for R1 and R2). This woduld have made the investigations in the IR spectra controlled and thus more conclusive. The errors in the NMR were not consistent and thus further investigation is required to verify the magnitude of error on a 13C NMR (using CDCl3 as the solvent). The geometries seemed to be accurate however investigations using computated molecular surfaces (i.e. FMOs) might have made the bending around the bridging carbon, and the slants between the two benzene rings and the triazole ring.

Conclusion

In this investigation different molecular modelling methods were tested and limitations were observed in the simpler methods. The more interactions a mechanism model takes into account the more time it takes for it to process the computation but it is certainly more accurate in terms of chemical interactions. Some conclusions were made from complex methods used on fairly complex molecules in the mini-project. There were still some errors but the investigation was believed to have been a success.

References

- ↑ J.A. Norton, "The Diels-Alder Synthesis, Chem. Rev., 1942, 31 (2), 319–523 DOI:10.1021/cr60099a003

- ↑ S.W. Elmore, L.A. Paquette, "The first thermally-induced retro-oxy-cope rearrangement", Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319, DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P.v.R. Schleyer, "Evaluation and prediction of the stability of bridgehead olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103 (8), 1891-1900 DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ D. Whitfield & T. Nukada, "DFT studies of the role of C-2-O-2 bond rotation in neighbouring-group glycosylation reactions", Carbohydrate research, 342 (2007), 1291-1304 DOI:10.1016/j.carres.2007.03.030

- ↑ Kolb, H. C.; Sharpless, K. B. Drug DiscoVery Today 2003, 8, 1128

- ↑ J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15998; DOI:10.1021/ja054114s

- ↑ Supporting Info, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15998; DOI:10.1021/ja054114s