Rep:Mod:ht1010

The Cope Rearrangement

In the experiment below, we have studied the [3,3]-sigmatropic shift rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene, commonly known as the cope rearrangement. The reaction occurs in a concerted fashion via either a boat or chair transition state, with the chair transition state several kcal/mol lower in energy than the more highly strained boat. In this experiment we will use the Hartree Fock, Becke three-parameter Lee-Yang-Parr exchange-correlation functional and quadratic synchronous transit 2 methods within Gaussian to probe the transition states of the cope reaction. This has previously been shown to give values in very good agreement with experimental values.

Optimizing the reactants and products

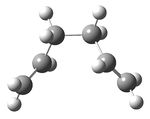

A molecule of 1,5-hexadiene with an anti peri-planar conformation for the central four C atoms was drawn in gaussview and the structure cleaned. The structure was then optimized using the Hartree Fock method and 3-21G basis set to give the structure shown below in figure 1, with a calculated energy of -231.69253528 a.u. This was then symmetrized (which did not observably change the structure) and shown to belong to the Ci point group.

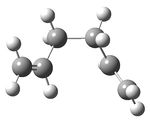

A molecule of 1,5-hexadiene with a gauche conformation for the central four C atoms was drawn in gaussview and the structure cleaned. The structure was then optimized using the Hartree Fock method and 3-21G basis set to give the structure below with a calculated energy of -231.69266122 a.u. This was then symmetrized (which again did not observably change the structure) and shown to belong to the C1 point group.

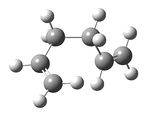

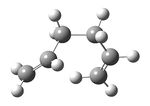

On first inspection, this was a surprising result, as it was assumed that anti peri-planar conformations of the molecule would be more stable than gauche conformations because of the greater dihedral angle within them and so less steric strain. As such, another anti per-planar conformation was drawn, cleaned and optimized using the Hartree Fock method and 3-21G basis set to investigate this anomaly further. The resulting structure, shown below in figure 3, was then symmetrized revealing a point group of C1 and its energy was found to be -231.69097054 a.u.

This energy value was again surprisingly higher than that of the gauche structure in figure 2 and when the calculations were then compared with a provided table of the low energy conformers of 1,5-hexadiene and their point groups, as shown in Appendix 1[1], it confirmed the finding that the structure shown in Figure 2 (identified in Appendix 1 as Gauche3) is the lowest energy conformer. To probe the stability of the gauche3 conformer, its HOMO and LUMO were generated using an HF/3-21G energy calculation as shown below in figure 4 and figure 5.

|

|

As can be seen from the HOMO, there is a significant stabilising overlap between the π orbitals of each of the alkenes, which would be impossible in the anti peri-planar conformers. Additionally, as can be seen from the LUMO, there is a significant stabilising overlap of the σ bond next to the alkenes with the π* orbitals of the alkenes. These electronic factors are the reasons for the excess stability of the gauche3 conformer.

The two conformers shown in Figures 1 and 3 were identified as Anti2 and Anti4 respectively and the provided table also gave added confidence in the calculations, as the energies calculated for the conformers are all in agreement with those provided.

The Ci anti2 conformation (previously optimized using the Hartree Fock method and 3-21G basis set) shown in figure 1 was then optimized again via density functional theory, using the Becke three-parameter Lee-Yang-Parr exchange-correlation functional and the 6-31G(d) basis set. This yielded the structure shown below in figure 6 with a calculated energy of -234.55969667 a.u. and as can clearly be seen, although the energy changed a fair amount from -231.69253528 for the HF/3-21G to -234.55969667 for the higher level B3LYP/6-31G, the geometry of the two were very similar.

As the energies calculated thus far only represented the bare potential energy surfaces of the molecules, additional terms had to be added so that comparisons could be made to empirical results. As such, a frequency calculation was conducted on the B3LYP/6-31G optimized anti2 conformer (again using the B3LYP/6-31G method). As expected, all of the vibrational frequencies obtained were positive, thus confirming the conformer was at an energy minima and so was a correctly optimised structure. This frequency calculation also produced the following thermochemical data for the species:

- Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.416252 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.408952 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.408008 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.447896 a.u.

Optimizing the chair and boat transition structures

The chair and boat transition structures of the Cope rearrangement consist of two CH2CHCH2 allyl fragments seperated by roughly 2.2 Å, one with C2h symmetry and the other with C2v symmetry. As such, to investigate the two transition structures, a CH2CHCH2 allyl fragment was first optimized using the Hartree Fock method and 3-21G basis set resulting in the optimized fragment shown in figure 7 below:

By duplicating this fragment and manually positioning the terminal ends of the fragments approximately 2.2A apart to approximate the chair transition state. The transition structure was then optimized by running an optimization and frequency calculation using the Hartree Fock method and the default basis set 3-21G to produce the optimized transition structure shown below in figure 8. The frequency calculation produced an imaginary vibration with frequency of 817.97cm^-1, which as can be seen from the animation below in figure 9, does indeed corresponds to the cope rearrangement.

|

|

Having located the chair transition structure, we then wanted to determine the boat transition structure and to achieve this, we used the quadratic synchronous transit 2 method. This involved first duplicating the already B3LYP/6-31G optimized 1,5-hexadiene molecule labelled anti2 and then manually changing the atomic numbering of one of the pair so that its numbering corresponded to that of the product of a cope rearrangement of the other. A QST2 transition state optimization and frequency calculation was then run on the structures which produced the transition structure shown in figure 10 below.

As can be seen, the resulting transition structure was not the optimal boat structure. This is because the QST2 calculation's linear interpolation between the two structures resulted in a simple translation of the allyl fragments and so did not take into account the more optimal bond rotations possible. To overcome this problem, the geometries of the two input structures were adjusted so that they were closer to the desired boat transition structure. This was accomplished by changing the dihedral angle of the central 4 carbon atoms of the reactant and product structures to 00 and then reducing the C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5 angles to 1000. This successfully produced the structure of the boat transition state as shown in figure 11 below. As can be seen from the animation below in figure 12, the vibration calculated does correspond to the cope rearrangement and as only one imaginary frequency was produced, the results confirm that the structure obtained was a transition state.

|

|

As the energy of the chair transition structure was calculated to be lower than the energy of the boat transition structure, the activation energy of the Cope rearrangement via the chair transition state must be lower than via the boat and as such, the chair will be the kinetically favoured pathway.

Although the boat transition structure looks like it could connect the gauche3 conformer and the chair transition structure could connect the gauche2 conformer, in reality predicting definitively by sight is impossible. As such, the intrinsic reaction coordinate method is used to follow the reaction pathway down the maximum energy gradient and in doing so, predict which conformer is connected to each transition structure. We ran HF3-21G IRC calculations with 50 IRC points on the chair and boat transition structures previously found and as our reaction coordinate was symmetrical, we only needed to calculate the IRC in the forward direction. For both the chair and the boat, the minimum geometry was still not reached at the end of this calculation and so three separate courses of action were available to us:

1. Optimize from the final point on the IRC.

2. Rerun the IRC with more points.

3. Rerun the IRC and compute force constants at each step.

In turn, each method was employed to compare its success, the results of which are shown below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The IRC 50 calculation for the boat transition structure did not reach the minimum structure as can be seen in figure 16 as its energy vs IRC graph does not reach its asymptote. However, as can be seen in figure 18. the optimization of the final structure from the IRC 50 resulted in the gauche3 conformer which fitted with our earlier prediction. As shown above in figure 22, the IRC 150 calculation did reach an asymptote, but whilst its structure is similar to that of gauche3, it is still noticeably different. The constantly recalculating force constant IRC 50 calculation appeared to reach asymptote, but it presented a similar structure to the IRC 150 calculation, which again does not fit any of the minimum energy structures.

The IRC 50 calculation for the chair transition structure did not reach the minimum structure as can be seen in figure 14. But an optimization of the final structure resulted in the gauche2 conformer as shown in figure 17 and as previously predicted. The IRC150 did reach the minimum structure as its energy graph reached its asymptote as shown above in figure 20 and the resulting structure was gauche2 as predicted. The constantly recalculating force constant computing IRC did not appear to produce a minimum as the energy graph did not reach its asymptote, yet despite this, the resulting structure was very similar to the gauche2 structure.

To find the activation energies for the reactions via the boat and chair transition structures, the chair and boat structures found earlier were then optimized further and frequency calculations run, again using the Becke three-parameter Lee-Yang-Parr exchange-correlation functional and the 6-31G(d) basis set. The resulting structures are shown below in figures 27 and 28 and by comparison with the HF structures, it is clear that this optimization at the higher level of theory did not significantly affect the structure.

|

|

Although the structures resulting from the B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculation are not significantly different from the HF/3-21G, the energies of the Boat and Chair structures from the B3LYP/6-31G(d) of -234.351359 a.u. and 234.362677 a.u.. respectively are significantly different. From this we assumed that it was time efficient to first locate the structure from the Hartree Fock and then to optimize using the higher level B3LYP/6-31G(d) to accurately calculate the energy. The frequency calculations on the two species produced the following thermochemical data for each:

Chair:

- Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.362677 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.356763 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.355818 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.391606 a.u.

Boat:

- Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.351359 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.345042 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.344098 a.u.

- Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.380795 a.u.

The activation energy at absolute zero via each transition state was then calculated using this data, by subtracting the sum of electronic and zero-point energies obtained for the anti2 conformer from the sum of electronic and zero-point energies of the transition structure. Additionally, the activation energies at 298.15K were found by subtracting the sum of electronic and thermal energies for the anti2 conformer from the sum of electronic and thermal energies for the transition structure. The results of these calculations are shown in the table below, where the energy values have been converted into kcal/mol [2].

- Calculated activation energy (0k) boat = 40.7209 kcal/mol

- Experimental activation energy (0k) boat = 44.7 ± 2.0 kcal/mol

- Calculated activation energy (298.15k) boat = 40.1041 kcal/mol

- Calculated activation energy (0k) chair = 33.6188 kcal/mol

- Experimental activation energy (0k) chair = 33.5 ± 0.5 kcal/mol

- Calculated activation energy (298.15k) chair = 37.3299 kcal/mol

As shown, the values calculated are in reasonable agreement with the values provided[3] and so we can be confident in the success of our method.

Appendix 1 [4]

| Conformer | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees HF/3-21G |

Relative Energy/kcal/mol |

| gauche1 | C2 | -231.68772 | 3.10 | |

| gauche2 | C2 | -231.69167 | 0.62 | |

| gauche3 | C1 | -231.69266 | 0.00 | |

| gauche4 | C2 | -231.69153 | 0.71 | |

| gauche5 | C1 | -231.68962 | 1.91 | |

| gauche6 | C1 | -231.68916 | 2.20 | |

| anti1 | C2 | -231.69260 | 0.04 | |

| anti2 | Ci | -231.69254 | 0.08 | |

| anti3 | C2h | -231.68907 | 2.25 | |

| anti4 | C1 | -231.69097 | 1.06 |

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

In the experiment below we have studied The Diels Alder Cyloaddition reaction, which is a pericyclic reaction between a dienophile and a diene. As the Diels Alder is a pericyclic reaction, it occurs in a single concerted step, through only one transition state. As such, it is a perfect reaction to probe using computational analysis such as that which is detailed below. In this experiment we will use the Hartree Fock, Becke three-parameter Lee-Yang-Parr exchange-correlation functional and the semi-empirical Austin Model 1.

Cis-butadiene and Ethene

A molecule of cis-butadiene was drawn in Gaussian before being cleaned and optimised using the Hartree Fock method and 3-21G basis set. The resulting structure was then optimised again using the Becke three-parameter Lee-Yang-Parr exchange-correlation functional and 6-31G basis set resulting in the structure in figure 29 below. The HOMO and LUMO for the structure was then obtained as shown below in figures 30 and 31, which also shows their symmetries.

|

|

|

HOMO = Antisymettric |

LUMO = Symmetric |

The symmetries of the HOMO and LUMO with respect to the σv plane for the structure are also shown above. A guess at the transition state for the reaction between the cis-butadiene and ethene was then drawn. As the transition structure has an envelope shape to maximise π overlap between the reactants, the guess structure was drawn by first drawing a bicyclic system and then removing the bridging –CH2-CH2- fragment. The interspecies transition state bond length was set to 2.2A and the structure was then optimised and the frequency calculated using the constant force constant calculating Berny transition state method, the Hartree Fock method and 3-21G basis set. The resulting transition structure is shown below in figure 32 as well as the vibration corresponding to the bond formation shown in figure 33.

|

|

The bond lengths of the partially formed C-C σ bonds were found to be 2.209A which was in the expected range because typical c-c bond lengths are 1.54A. Moving from the reactants to the transition structure, the C-C bond length in the cis-butadiene contracts to 1.394A, this is also expected as it is in the process of forming a C=C, the typical length of which is 1.32A. The previous C=C bond lengths in the transition structure are all significantly greater than in the starting molecules, with the C=C in the ethene fragment expanded to 1.376A as it transitions into the longer typical c-c bond length. All of the above results were as expected given the lengthening of C-C bonds changing from sp2 to sp3 and the contraction when changing from sp3 to sp2. As the van der waals radius of a carbon atom is 1.7A, the sum of the van der waals radii is actually larger than the interspecies distance in the transition structure. This means the partial C-C σ bond in the transition structure, is in fact a bonding interaction. The imaginary frequency of -818.37cm-1 illustrated in figure 33 above, does correspond to the Diels Alder bond formation, and is certainly a concerted process as the bond formation happens at the same time. In contrast, the lowest positive frequency of 166.52cm-1 corresponds to an asynchronous mechanism. The calculated HOMO and LUMO of the transition structure are shown below in figure 34 and 35. As can be seen, the LUMO of the transition structure is symmetric with respect to the reflection plane and the HOMO is anti-symmetric. The HOMO is formed from the interaction of the HOMO of butadiene and the LUMO of the ethene and so as orbital symmetry is conserved, the reaction is therefore allowed.

|

|

Maleic Anhydride and Cyclohexa-1,3-diene

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene readily undergoes a Diels Alder cycloaddition reaction with maleic anhydride, the mecahnism of which we have probed below. The endo product is the major and kinetic product in the reaction and so it was assumed that the Exo transition state was higher in energy than the Endo.

To calculate the structure of the transition state, an approximation of each of the transition strutures was needed. To create this, the cyclohexadiene part of the transition state was first approximated by drawing and HF/3-21G optimizing a bicyclo structure structure and then removing one of the bridging CH2CH2 to create the desired fragment. Maleic Anhydride was then drawn and HF/3-21G optimized to approximate the other half of the transition state. The Exo and Endo transition states were then approximated by guessing an interfragment bond length of 2.2A and orientating the two fragments to the approximate orientations expected in the exo and Endo product. An HF/3-21G transition state (Berny) optimization and frequency calculation with constantly calculating force constants was then carried out on each of the approximated transition states resulting in the structures shown below in figures 36 and 37. The energy of the Exo transition state was found to be -605.60359125 a.u. and the energy of the Endo transition state was found to be -605.61036823 a.u. As the energy of the Endo transition state is lower than the energy of the Exo transition state, we could confirm the empirical observation that the reaction via the Endo transition pathway was the kinetically favored route. This is also a qualitatively reasonable as there is likely to be considerable steric repulsion in the Exo transition state between the bridging carbons in the cycoheadiene and the oxygen groups on the maleic anhydride which is not present in the Endo state. The effect of this steric hinderence could also be seen directly by the increased inter-fragment bond length of 2.2607A in the Exo state compared to 2.23099A in the Endo state and also by the increased through space distance between the -(C=0)-0-(C=O)- and the bridging CH groups (3.026A vs 2.848A). The rest of the bond lengths in the transition states agreed with the range of expected values, with the maleic anhydride double bond having taken on significant single bond character as it had lengthened to 1.370A and 1.407A and the cycloheadiene fragment double bonds also having lengthened to 1.398A and 1.371A.

|

|

|

|

Each of the structures only had one negative vibration, which equaled -647.44cm-1 for the Exo state and -643.52cm-1 for the Endo state. Both of these vibrations are shown below in figures 38 and 39 (to view vibration, please click on image) and these clearly correspond to the bond formation of the Diels Alder reaction. The vibrations also show that the bond formation is concerted as expected.

|

|

Semi empirical Austin model 1 calculations were then performed on each of the transition states to give the molecular orbitals, the HOMO and LUMO of which are shown below in figures 40 to 43. As can be seen from the HOMOS of the species, there is no visible secondary orbital overlap for either of the transition structures. As such, the kinetic preference for the Endo product is solely due to the steric hindrance in the Exo transition state and not to do with secondary orbital interactions. Although often touted as the explanation for many Diels Alder reaction preferences[5][6], the true influence of secondary orbital interactions has been called into doubt by some including Garcia et al. who suggested that Diels Alder preferences stemmed instead from more common effects such as solvent effects, steric interactions, hydrogen bonds and electrostatic forces [7]. The results of this experiment seems to side with those of Garcia et al. and so further computational investigation into other reactions said to be dominated by Woodward and Hoffmann's secondary orbital interactions would be interesting.

|

|

|

|

The cycohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride reactants were then drawn, cleaned and B3LYP/6-31G optimized. Energy calculations were then carried out on the resulting structures using the AM1 semi-empirical method to produce the molecular orbitals of the reactants. The HOMO and LUMO of each of each of the reactants are shown below in figures 44 to 47. The HOMO and LUMO of the maleic anhydride were symmetric and anti-symmetric respectively.Additionally, the HOMO and LUMO of the cyclohexadiene were found to be anti-symmetric and symmetric respectively.

|

|

|

|

Conclusion

The experiments carried out have been successful in elucidating the transition states of the cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene; the Diels Alder cycloaddition of Cis-butadiene and Ethene and finally the Diels Alder cyloaddition of Maleic Anhydride and Cyclohexa-1,3-diene. We have used a wide variety of computational techniques and have confirmed several experimental findings, whilst also having confirming the shortcomings of several techniques. Perhaps the most interesting result we obtained was discovering the very minimal effect that secondary orbital interactions had on the the Diels Alder reaction studied. As we have only studied this effect for one molecule, no wide conclusions can be drawn and once very plausible explanation would be that this may have resulted simply because of incorrect assumptions made by our theory. Further investigation into the extent of SOIs on Exo/Endo preference would however be very interesting given the already heated debate surrounding their influence and this would involve studying a wide range of reactants and also using higher levels of theory to give more confidence to our findings.

References:

- ↑ Appendix 1, Phys3 Lab Manual, Imperial College London [1]

- ↑ NIST fundamental physics constants [2]

- ↑ Optimizing chair and boat transition structures, Phys 3 Lab manual, Imperial College London[3]

- ↑ Appendix 1, Phys3 Lab Manual, Imperial College London[4]

- ↑ Hoffmann, R; Woodward, Orbital symmerties and Endo-Exo Relationships in Concerted Cycloaddition Reactions R.B.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1965,87, 4388-4389

- ↑ Hoffmann, R; Woodward, R.B.Orbital Symmetries and Orientational Effects in a Sigmatropic Reaction. J.Am.Chem.Soc.1965,87, 4389-4390

- ↑ García,Mayoral, Salvatella. Acc. Chem. Res., 2000, 33 (10), pp 658–664 [5]

Log Files

File:HT1010-FIGURE1Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE2Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE3Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE4&5Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE6Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE7Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE8&9Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE10Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE11&12Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE13&14Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE15&16Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE17Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE18Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE19&20Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE21&22Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE23&24Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE25&26Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE27Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE28Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE29Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE30&31Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE32&33Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE34&35Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE36,38,40,41Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE37,39,42,43Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE44,45Log.txt

File:HT1010-FIGURE46,47Log.txt