Rep:Mod:hgmd2

Module 2

by Hayleigh Gascoigne

Computational chemistry can be used to predict the structures and molecular orbitals of certain molecules. From this, reactivity and other properties such as bond angle and length can be found. There are limitations to these methods however, and so all the data is associated with some error.

BH3

A molecule of BH3 was drawn in GaussView and optimised. This optimisation calculation is broken down into two parts, the first being SCF and the second being OPT. In SCF, the positions of the nuclei (in this case B and H) are fixed and the electron density and energy are calculated using Schrodinger's equation. In the OPT part, the positions of the nuclei are moved around and the SCF calculation repeated until the geometry with the lowest energy is found. The method, determining the type of approximations made, used for BH3 was B3LYP and the basis set, determining the accuracy, was 3-21G. 3-21G is a split valence basis set[1]. This means it is a minimal basis set since it simply calculates a double zeta for the valence orbital, as the inner-shell orbitals are not considered as such an important contribution. It has quite a low accuracy but it is quick, and therefore efficient. Here is the optimised molecule.

An Natural Bond Orbital Analysis was carried out on the molecule. The NBO charge for Boron was 0.337 and for Hydrogen was -0.112

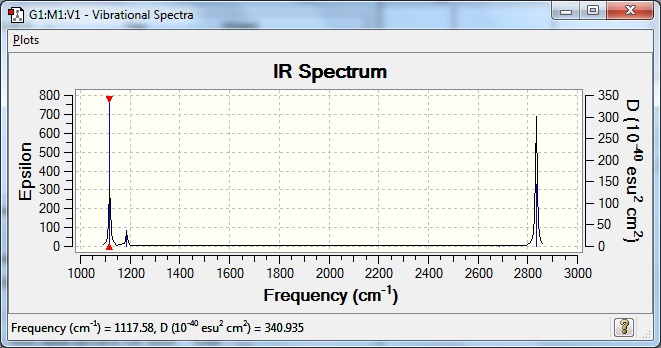

A calculation was done to predict the frequencies in IR spectrum. The animated vibrations are shown below along with the spectrum.

It is seen in the table that there are six (3N-6) vibrations, however there are not six peaks in the IR spectrum below. This is because two of the vibrations are degenerate and have the same frequency, hence they cannot be recognised separately on the spectrum. These degenerate frequencies are seen at 1186.21cm-1 and 2834.38cm-1. The vibration at 2687.50cm-1 is not seen on the spectrum because it is a symmetrical stretch, has a dipole moment and so is not IR active.

Here is the Molecular Orbital Diagram for BH3, made of a Boron and a H3 fragment orbital.

An MO analysis of BH3 was also done, and the method was set to energy rather than optimisation. These calculations of rea MOs are shown next to their corresponding MOs in the table below.

| 1a'1 | 2a'1 | 1e' | 1e' | 1a2 | 2e' | 2e' | 3a'1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It can be seen that the calculated MOs and the ones from the diagram match very well. This shows that the calculation worked well and the basis set used gave good enough approximations of the orbitals to give accurate results. It can be said, therefore, that this particular method and basis set is a useful one for a molecule such as this. However, if the molecule gets larger (ie more atoms) or the atoms become heavier, the approximations will break down and the MOs obtained may not match the qualitative MOs.

TlBr3

A molecule of TlBr3 was drawn in GaussView and an optimisation carried out on it. Alternatively to the BH3 molecule, the symmetry was restricted first. The point group was set to D3h, and the tolerance made very tight. The method used was the same as for the previous molecule but the basis set was LanL2DZ. This is a medium level basis set. This was required so that was more accurate as heavier elements are involved with this molecule.

The optimised Tl-Br bond distance was found to be 2.65Å, and the optimised Br-Tl-Br bond angle was found to be 120o. The literature value of the bond length was found to be 2.512Å [2]

Here is the optimised molecule.

chk filelog file

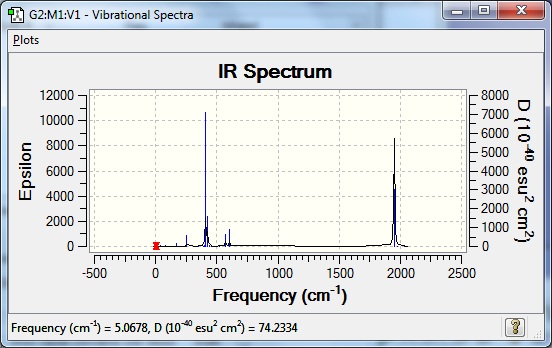

A frequency analysis was also carried out on the molecule and the same basis set was used. This is necessary as the basis set decides which aspects of the orbitals to use. If a different basis set is used, the results seen in the calculation will not be valid as different approximations of the orbitals will have been used for each part.

The low frequencies for TlBr3 are as follows.

| Low Frequencies | Low Frequencies |

|---|---|

| -3.4213 | 46.4289 |

| -0.0026 | 46.4292 |

| -0.0004 | 52.1449 |

| 0.0015 | |

| 3.9367 | |

| 3.9367 |

The six on the left are the -6 part of the 3N-6 vibrational frequencies and they are the motions of the centre of mass of the molecule. As required, all are smaller than the other three listed frequencies, and the largest zero frequency is an order of magnitude smaller. As these are particularly small, it shows the calculations done were accurate. The lowest real normal mode is 46.4289 as this matches the lowest frequency seen on the spectrum.

GaussView sometimes omits bonds from the drawing and optimisation of certain molecules. It has a certain range of bond lengths programmed into it, and so if anything falls outside of this, GaussView considers there to be no bond there. In reality, this does not necessarily mean that there isn't a bond there. A bond is not a physical line in space between two atoms meaning they are joined together. Rather, a bond exists where it is favourable for atoms to be close to each other, have a good orbital overlap and share or donate electrons, and lower their energy in doing so. However, the distance between two atoms in a 'bond' is hard to define. At what distance is there no longer a bond between two atoms? Depending on the size of the atoms and the extent of the overlap, it is different.

Cis and Trans Isomerism of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 exists in two forms, the cis and trans isomers. Calculations were performed on both forms of this molecule, in order that the structures be optimised and then the vibrational spectra analysed. The phenyl ligand is very big and so it takes a lot of computing power to calculate. Instead a chlorine ligand was used, as it is still big and so would represent phenyl reasonably well, but as less atoms are involved, less computing power is needed.

Here are the molecules before optimisation.

Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 was drawn in GaussView and the structure was optimised, this time using SCAN instead of Gaussian as more power was required due to the size of the ligands. The B3LYP method was used, and low level basis set, LANL2MB, was used at first so the geometry was approximately correct. If the calculation was done with a higher level basis set on a structure that wasn't at least close to the real one, a local minima in the energy may have been found and then any information taken from that would be invalid, and not accurate. Also, therefore, in the additional keywords was written "opt=loose".

Once the optimisation was received, it was realised that the dihedral angles were not described well, and so these were set using GaussView. In the cis conformer, this was done so that one Cl in one group was pointing up parallel to the axial bond, whilst rotating the whole PCl3 group, and the other PCl3 was rotated such that one Cl was pointing down parallel with the axial bond. For the trans conformer, the PCl3 groups were rotated such that a Cl from each one eclipsed the same equatorial carbonyl group. This newly better described molecule was once again sent to SCAN for optimisation, but this time using a higher level basis set, LANL2DZ. "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9" was also written in the additional keywords. Once done, the files were submitted to D-space and can be seen here.

A frequency calculation was then carried out, and the same basis set was used, and the additional keywords retained. Once the job was received back the frequencies were analysed. It was seen that there were no negative frequencies. The files were submitted onto D-space and are shown below:

The geometries of these optimised molecules were studied and are visualised below.

For the cis isomer, the Mo-P distance was measured at 2.51Å and the literature[3] value was found to be 2.576Å. These values are quite close. The P-Mo-P angle was measured from the optimised structure to be 94.2o, whereas the literature[3] was found to be 104.62o. This is quite significantly different, and so highlights the limitations of the basis set, and the accuracy of the output. The structure is not the one found in reality, and so in order to improve the accuracy of the calculated structure, a better starting geometry must be used. An energy minima was reached since none of the frequency outputs were negative, but this was probably a local minima.

For the trans isomer, the Mo-P distance was measured from the optimised structure to be 2.44Å whereas the literature[3] value is 2.500Å. This the same difference in literature and measured value as before, ~0.06Å. This could be to do with the fact that the phenyl group (from the literature) has been replaced with a Cl in the computational method, and thus the error is consistent. It can be seen that the Mo-P bond distance is shortened for the trans complex. This is thought to be due to the cis PR3 elongating their bonds in order that the unfavourable non-bonding interactions between the bulky groups be avoided. This is further proved by the investigation of the Mo-P bond length in the complex Mo(CO)5PPh3, which in the literature[3] was found to be 2.56Å, shorter than the value for the cis complex, as there are little steric interactions. The Mo-C bond was measured as 2.06Å and in the literature was 2.005Å[3]. Again, this shows the same error as before. The geometry is a distorted octahedron due to the bulk of the chlorines and so the angles are expected to be distorted too. The P-Mo-P bond angle was measured as 177.4o and the P-Mo-C bonds were measured as 88.7o and 91.3o. The P-Mo-C angles were found in literature[3] to be 87.2o and 92.1o. These match quite closely and so it is thought that the optimised structure was very close to the structure found in reality. As to why the trans isomer was a better optimisation than the cis is probably to with the fact that there is less room for error, and a change in the structure for trans as there is more symmetry in this molecule. With the cis isomer, there are probably a few more different conformers.

There is not a large difference between the energies of the molecules, in fact including error, the energies are the same. The cis isomer has the energy -623.577 hartree, as reported in the summary file whilst the trans isomer has the energy -623.576 hartree. Both of these are -1635680 kjmol-1.

Although the energy is the same, it is thought that the trans isomer is more stable. This is because chloride is a bulky group and if two lie cis to each other, the sterics will be unfavourable and it is not expected that this isomer will occur in significant quantities.

To make the cis isomer more stable, the size of the R group in PR3 can be decreased and as there will be less steric clash, the cis isomer will be more likely to occur.

Here are the low frequencies and their animations.

| Trans Frequency | Trans Animation | Cis Frequency | Cis Animation</ref> |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 |  |

10 |

|

| 6 |  |

17 |

|

The lowest frequencies show rotations of the PCl3 groups. As these frequencies are so low, the movements are very facile as they do not require much energy and so occur easily at room temperature.

Here are the carbonyl stretching frequencies and the IR spectrum for the cis complex.

| Calculated Computational | Experimental | Literature[4] |

|---|---|---|

| 1945 | 1780.59 | |

| 1948 | 1840.52 | 1888 |

| 1958 | 1889.21 | 1914 |

| 2023 | 2012.47 | 2028 |

Only one peak is seen for the trans complex, and this is at 1950cm-1. The wavenumber of the peak found in experiment was 1892.17cm-1. The spectrum from the calculation is seen below.

Both isomers got the number of peaks expected, which is four for the cis complex and one for the trans complex. However, the wavenumbers for the calculated and the literature are quite different. This is because, the approximation that the calculation uses is an harmonic oscillator, which means on average, the wavenumbers are out by about ~100 as in reality bonds are like anharmonic oscillators.

Mini Project

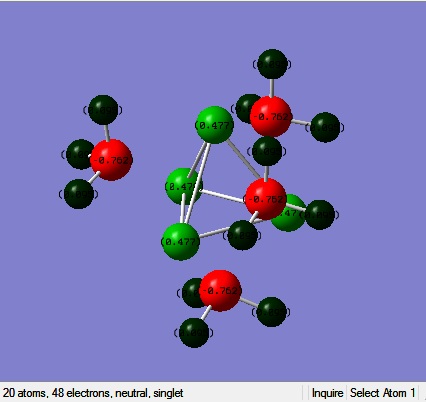

MeLi exists in cluster form as a tetramer. This is because lithium is intrinsically electron deficient, and so the deficiency is overcome be the formation of multicentre bonds. Increasing the alkali metal size, it would be expected that the bond length would increase, and different characteristics may be seen in the spectra. The tetramer structure of MeLi, MeNa and MeK was therefore investigated using computational chemistry. The MeLi tetramer was drawn in GaussView, and an optimisation was performed using B3LYP method and 6-311G (d,p) Basis Set. It was thought that this basis set would be adequate but not too complicated to cause inefficiency to the machine associated with the calculations. Again, this basis set is split-valence basis set[1]. On these optimised structures was then performed a frequency analysis, to see if the structures found were a minimum. Finally, a calculation was performed on the original structure of MeLi so that it's molecular orbitals could be visualised. Also, various parameters for each molecule were compared.

MeLi

The methyl lithium tetramer forms the basis for the all the structures, as this is the one known to exist. The other molecules were built from this, so that hopefully the optimisations would be shorter, and thus more efficient. Here is the optimised structure as received from SCAN.

The optimisation proceeded, terminated normally and converged as expected. The optimisation was at a minimum, since there were no negative frequencies in the IR analysis. The structure looks different from the input file as the bonds are in a different place. This does not matter since GaussView defines bonds to a strict parameter and in reality, it can be seen that 2c-2e bonds cannot be placed in this molecule because it is a cluster.

MeNa

This optimised structure of MeNa was made from the previous optimised structure, by changing the Li atoms to Na atoms. The bonds were also lengthened since Na is a larger atom, and if the bonds were too short the atoms would clash and hence the optimisation may not work.

This job also finished as expected. The frequency analysis of this also confirmed that this structure was at a minimum. Again the bonds are in an unusual place. This time, however, not all the metal atoms are linked. As this metal is bigger, perhaps the program considers the bonding to be unfavourable.

MeK

This structure again was built by changing the metal atoms to K from a previous optimised structure. The bonds were lengthened further.

The job terminated normally, and on inspection of the log file, it had converged. The gradient was also of a reasonable magnitude. However, the IR frequency analysis revealed four negative frequencies, leading to the belief that the structure was not a minimum. The negative frequencies corresponded to a twisting of the methyl groups. It was decided therefore that this structure be optimised a second time, this time with greater Me-K distances to avoid the unfavourable interaction. On analysing the IR frequencies from the second optimisation, the same thing had occurred. Perhaps, this can be explained by the fact that the tetramer structure of MeK does not occur in reality, and there must be some reason for this. It is unfavourable for this particular structure of MeK to exist, perhaps due to the large difference in orbital size between carbon and potassium and hence the weaker bond, for this particular geometry. The literature suggests that the difference in electronegativity between carbon and potassium is such that the MeK structure is essentially an ionic lattice where there are 'CH3- ions with trigonal prismatic coordination to six K ions'[5].

Here is a table comparing parameters found for the various compounds.

| Li | Na | K | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M-C bond length (Å) | 2.19 | 2.59 | 2.97 |

| M-M bond length (Å) | 2.39 | 2.97 | 3.67 |

| Relative Energies (kjmol-1) | -498537 | -2123770 | -6719790 |

| IR spectra |  |

|

|

One literature[6] value stated that the Li-Li distance in tetrameric MeLi was 2.44Å and the Li-C distance was 2.33Å, which was obtained from the x-ray structure. Another literature[7] value that was obtained by a computational study was found to be 2.40Å for Li-Li and 2.20Å for Li-C. The method and basis set used was B3LYP/6-31+G(d). This is slightly worse than the one that was used for this report. It can be seen that the values obtained are close to the computational ones in the literature, but not so close to the actual ones. And so, it is thought the structure is proved to be at a minima since it matches another's literature and the difference to the distances in x-ray structure are inherent to the calculation and basis set involved. It was seen in the literature[5] that Na-C bond distances were '253 to 291 pm', and the calculated bond distance lies within this. So the structure obtained is around what is seen in reality.

The M-M stretch, or breathing motion, was investigated for each structure in order that each molecule can be compared. The Li breathing motion occurred at 550cm-1, the Na one occurred at 244cm-1 and the K motion was not accurate as the structure was a local maxima. This is a decrease in wavenumber down the group. This suggests that as the metal size increases, the strength of the bond decreases. This is expected, as the orbital overlap of metal and carbon becomes poorer down the group, owing to the growing size of the metal orbital. Poorer orbital overlap means a weaker bond.

An NBO analysis was done for MeLi.

Where the more red an atom, the more negative it is, and the more green an atom, the more positive it is. The analysis showed that the charge on the carbon atoms was -0.762 and for the the lithium atoms it was 0.477. In the literature[8], the NPA charge, which was carried out using the B3LYP method and the 6-31+G* basis set, was found to be 0.86 for Li and -1.51 for C. The values, although quite different, have the correct sign and show the the Li-C bond to have a certain amount of ionic character, despite it being largely covalent. The values are different because firstly a different basis set was used and secondly it is assumed that an NPA analysis uses different approximations to an NBO analysis.

The molecular orbitals were calculated for the original MeLi tetramer structure and a few are shown below.

| HOMO-3 | HOMO-2 | HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 | LUMO+3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It can be seen in the LUMO that there are large vacant orbitals around the lithiums. This explains MeLi's nucleophilic character and why it's particularly air and moisture sensitive. The large vacant orbitals are open to attack by lone pairs from the oxygen on water. From the HOMO-3, it can be seen that there is a strong bonding interaction along the C-Li bonds, as there is a lot of electron density around this area.

A deeper MO, No 14, is pictured here.

This one has been chosen because it is particularly interesting, the orbital interaction between opposite carbons looks like a bow! It means that there is some overlap between these carbon atoms, and thus a bonding interaction. This strengthens the molecule overall.

In conclusion of the mini project, it can be seen that with the exception of the MeK structure, all the calculations worked well and were reasonably close to literature. The basis set used was appropriate, and the data could be used to give reasons for the reactivity of MeLi.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 ChemViz - Basis Sets. [1]

- ↑ J. Glaser and G. Johansson, On the Structures of Thallium (III) ions and its Bromide Complexes in Aqueous Solution, Volume 36a, 1982, 125-135. [2]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Crystal Structures of trans-[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2, Inorganica Chimica Acta, Volume 254, 1997, 167-171. [3]

- ↑ R. L. Keiter, M. J. Madigan, Tetracarbonyl Group 6 Complexes containing secondary and tertiary Phosphines, Journal of Organometallic Chemistry, 331 (1987), 341-346. [4]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 E. Weiss, Structures of organo alkali metal complexes and related compounds, Angewandte Chemie, Vol 32, 1993, p1501-1670 [5]

- ↑ M. Tacke, R. Leyden, L. P. Cuffe, A DFT study of the reactions of tetrameric and hexameric methyllithium with CO and CNMe, Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM, Volume 684, 2004, Pages 211-215. [6]

- ↑ Y. Ohta, The Body-Centered Cubic Structure of Methyllithium Tetramer Crystal: Staggered Methyl Conformation by Electrostatic Stabilization via Intratetramer Multipolarization, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2006, 110 (25), pp 12640–12644[7]

- ↑ O. Kwon, F. Sevin, M. L. McKee, Density Functional Calculations of Methyllithium, t-Butyllithium, and Phenyllithium, Oligomers: Effect of Hyperconjugation on Conformation, J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 913-922 [8]