Rep:Mod:hay147

Module 1: Structure and Spectroscopy using Molecular Mechanics and Molecular Orbital Theory

Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

In the following article, molecular mechanics will be used to predict the molecular geometries of a variety of compounds, along with the regioselectivity which is involved during their reaction. Molecular mechanics is a powerful technique which allows analysis of conformations in terms of their bond lengths, angles, sterics and van der Waals interactions. Molecular mechanics models molecular systems using Newtonian mechanics, the general principle of which involves determining the potential energy of a system using force fields.

Typical assumptions invoked by molecular mechanics programs include simulating individual atoms as single particles, allocating each particle with values relating to polarisability, net charge and atomic radius (typically the van der Waals radius), and interpreting bonding interactions in a classical manner: as springs, which then have an equilibrium distance equivalent to the calculated bond length.

Force fields determine the potential energy of a system as a function of both covalent and non covalent interactions:

Etotal = Ecovalent + Enoncovalent, where the covalent energy contributions include bond, angular and dihedral energies, and the non-covalent energies include electrostatic (dipole/dipole) and van der Waals contributions.

These van der Waals contributions are modelled on a Lennard-Jones 6,12 potential, i.e. attractive interactions fall off with 1/r6, and repulsive interactions fall off with 1/r12, thereby showing a strong distance dependence.

The electrostatic interactions are typically modelled using Coulomb’s law. These display a less severe distance dependence than the van der Waals contributions, which can render calculations difficult, as longer range interactions become more difficult to compute. Typical solutions involve using either a sharp cutoff radius, or using a scaling function to moderate the predicted electrostatic energy.

To finalise the energy contributions to the system, force constants and van der Waals multipliers must be taken into account, along with values of the equilibrium bond lengths, bond angles, dihedral angles, partial charges and atomic masses.

This combined medley of energies and parameters is collectively termed a force field.

Allinger’s[1] 1977 MM2 molecular mechanics model will be used to perform the analysis of the compounds. This can be found within the ChemBio3D program.

The MM2 model is widely used in academia. MM2 is a second-generation force field which has superceded the classical force fields due to its better fits to experimental data, and it is suitable for a broader range of molecules than the classical force fields.

Notable advances in the MM2 force field, relative to the MM1 force field, are that it contains an independently variable van der Waals parameter, (previously this had simply been taken to be the mean of H-H and C-C interactions), and the inclusion of other key parameters, namely the V1 and V2 torsional potential terms. These terms are insignificant in the case of symmetric molecules (they cancel out), but as the majority of the compounds analysed below do not have a plane of symmetry, a higher degree of accuracy should be observed in using the MM2 force field, due to the inclusion of these V1 and V2 torsional terms. The major change attributed to these V1 and V2 terms is the fact that the hardness/size of hydrogens can be adjusted, meaning the resulting force field will be able to better optimise molecular geometries.

The consensus for the MM2 force field is that overall it performs a better job not only for hydrocarbons (as was the standard for first generation force fields), but also other functionalities present within structures. One notable improvement is that of halides, due to the ability to include softer hydrogens. This will be important for compound 12 below, which contains a chlorine atom.

Finally, the entire field of C-H bond lengths has been improved relative to the MM1 model, by using electron diffraction bond lengths as opposed to the 1973 MM1’s microwave bond lengths, which were around 0.1 Å shorter than experimental data. This improvement is sensible, as the remainder of the structure is calculated using electron diffraction bond lengths, and should lead to a more uniform distribution of bond lengths within the structure.

More recently, MM3 and MM4 models have been released, though these are not available on the version of ChemBio3D being used to analyse the structures below.

The energy output from the MM2 force field is given in terms of different energy contributions: stretching, bending, torsion, van der Waals and dipole/dipole terms. The magnitude of these terms indicates the difference from a ‘normal’ situation, i.e. a highly positive energy contribution suggests that this energy parameter is widely different from the ‘natural’ magnitude of the parameter. This is most likely due to geometric effects. This will be taken into account when analysing the minimised energies of the structures below.

In addition to the MM2 force field, a slightly different MMFF94 force field will also be used, along with a MOPAC PM6 analytical technique. This is a non-molecular mechanical technique, instead using molecular orbitals to rationalise stereochemistry and reactivities.

The Hydrogenation of a Cyclopentadiene Dimer

It has been found that cyclopentadiene will dimerise in a Diels-Alder reaction to produce an endo dimer rather than an exo dimer:

Analysis of the relative energies of both the endo and exo dimer using the MM2 force field gives the following results:

| Energy parameter | Endo energy (kcal mol-1) | Exo energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2552 | 1.2813 |

| Bend | 20.8259 | 20.5698 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.8336 | -0.8372 |

| Torsion | 9.5117 | 7.6674 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.4986 | -1.4154 |

| 1,4 VDW | 4.3097 | 4.236 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.4452 | 0.3778 |

| Total energy | 34.0136 | 31.8796 |

These results show that the endo dimer is over 2 kcal mol-1 higher in energy than the exo dimer. As the endo dimer is the major product of Diels-Alder reactions, this suggests that the endo product is the kinetic product of the dimerisation reaction, with a lower energy transition state than that found during formation of the more thermodynamically stable exo product. The exo product, though thermodynamically more stable, must have a higher energy transition state en route to product formation. This means the exo product is less likely to form under non-equilibrating conditions. The endo transition state involves secondary orbital interactions, which helps to stabilise the transition state, resulting in a lower energy barrier to product formation than that for the exo product.

Hydrogenation of the endo cyclopentadiene dimer tends to mainly give a dihydro derivative; the tetrahydro derivative can only be obtained after extensive hydrogenation conditions.

Analysing the energies of the two dihydro derivatives of the endo dimer should enable a prediction as to which product will form, by comparing their relative energies, and thus stabilities:

| Energy parameter | Energy of compound 3 (kcal mol-1) | Energy of compound 4 (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2279 | 1.1366 |

| Bend | 18.6932 | 13.0252 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.7442 | -0.5640 |

| Torsion | 12.8241 | 12.4289 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.3366 | -1.3408 |

| 1,4 VDW | 6.0390 | 4.4279 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1632 | 0.1410 |

| Total energy | 36.8666 | 29.2548 |

Performing an MM2 analysis of compounds 3 and 4 reveals that compound 4 is over 7 kcal mol-1 lower in energy than compound 3. This suggests that compound 4 is the more thermodynamically stable dihydro derivative. This suggests that hydrogenation of the bridged ring’s double bond is more facile than hydrogenation of the unbridged ring’s double bond. The hydrogenated product 4 has lower contributions to the total energy from stretching, bending, torsion, 1,4 VDW and dipole/ dipole energies. The major difference can be seen in the relative bend energies of the two compounds; compound 4’s bend energy of 13.0252 kcal mol-1 is much lower than compound 3’s 18.6932 kcal mol-1 bend energy. This is because the bond angles around the carbons forming the double bond in compound 3 are more distorted in the bicyclic ring than those around the double bond in compound 4. Compound 4 has a less distorted structure, meaning the bond angles are closer to their ideal values. All of these factors combine to give a more thermodynamically stable product in compound 4.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring (an NAD+ analogue)

Compound 5 is an optically active derivative of prolinol, which reacts with methyl magnesium iodide in an alkylation reaction with overall alkylation in the 4-position to generate the product, compound 6. The absolute stereochemistry of the product is shown below:

Compound 5 is an activated N-methyl pyridinium salt, which is susceptible to 1,4-attack using a Grignard reagent, to alkylate the 4-position of the ring. In this example, methylmagnesium iodide is the organometallic reagent .

N-methyl salts tend to undergo highly regio- and stereo-selective addition using Grignard reagents: selectivity of up to 99% has been observed[2].

The major diastereomer formed has the R-group from the Grignard oriented in an anti-orientation relative to the hydrogen present at the chiral centre (shown on above diagram).

This stereoselectivity is typical of many Grignard reagents.

Chelation control[2] has been suggested to account for such a phenomenon. This would involve the amide oxygen atom coordinating to the magnesium of the Grignard reagent, forcing the organic nucleophile of the Grignard to add onto the same face of the pyridinium ring as the carbonyl is orientated. Overall, this involves a 6-membered transition state.

The minor products (i.e. with the organic nucleophile’s R group syn to the chiral centre’s hydrogen) have been proposed to result from non-chelation controlled routes. Research has shown that allylmagnesium bromide has a lower selectivity than most Grignard reagents. This has been attributed to an organic dissociation mechanism involving transfer of the organic ligand; this may involve allylic carbocations or allylic radicals.

The reactivity of Grignard reagents contrasts markedly from those of organolithiums – these show stereo- and regio-random products, presumably due to the inability of the lone pair of the carbonyl oxygen to chelate to the lithium centre. This would mean that the organic nucleophile from an organolithium could attack from either the top or bottom face of the compound, resulting in a mixture of diastereomers.

Stereomodels formed by Drieding[2] illustrated that the 7-membered ring displayed very little conformational flexibility. An important finding from these stereomodels was that the carbonyl group could be either above the plane of the pyridinium ring (ie anti to the hydrogen at the chiral centre), or coplanar with the pyridinium ring. No conformation was found with the carbonyl group below the plane of the ring, syn to the hydrogen on the chiral carbon centre.

The high stereo- and regio-selectivity of Grignard reagents for these examples mean they have potential applications for diastereo- or enantio-selective alkaloid syntheses.

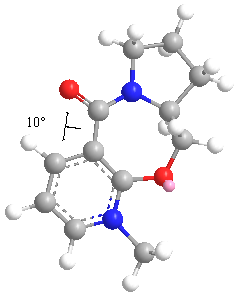

Bearing in mind the results from Drieding’s stereomodels, i.e. that the carbonyl group is either above the plane of the pyridinium ring, or coplanar with the ring, energies of possible conformations were calculated using the MM2 method; the dihedral angle was varied between 0 and 180o in order to compare the relative energies of the conformers:

| Dihedral angle (o) | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Charge/Dipole | Dipole/Dipole | Total energy |

| 1.0133 | 2.0956 | 14.5945 | 0.1349 | 4.8396 | -0.3873 | 16.6424 | 9.5599 | -4.0087 | 43.4709 |

| 2.0144 | 2.104 | 14.5414 | 0.1369 | 4.8204 | -0.4015 | 16.6206 | 9.5555 | -4.0112 | 43.3661 |

| 3.0104 | 2.0863 | 14.4971 | 0.1358 | 4.812 | -0.4171 | 16.6213 | 9.5559 | -4.0134 | 43.2778 |

| 4.0081 | 2.084 | 14.4477 | 0.1341 | 4.8163 | -0.428 | 16.614 | 9.554 | -4.0151 | 43.2068 |

| 5.0059 | 2.0781 | 14.402 | 0.1346 | 4.8378 | -0.4436 | 16.6078 | 9.5525 | -4.0172 | 43.152 |

| 6.0038 | 2.0629 | 14.3644 | 0.1335 | 4.8622 | -0.4574 | 16.6108 | 9.5527 | -4.0196 | 43.1095 |

| 7.0028 | 2.0603 | 14.3205 | 0.1345 | 4.9084 | -0.4743 | 16.5920 | 9.5556 | -4.0187 | 43.0784 |

| 8.0001 | 2.0591 | 14.2881 | 0.1334 | 4.9716 | -0.4910 | 16.5761 | 9.5514 | -4.0216 | 43.0671 |

| 8.9981 | 2.0531 | 14.2532 | 0.1311 | 5.0524 | -0.5139 | 16.5687 | 9.5484 | -4.0231 | 43.0699 |

| 9.9972 | 2.0377 | 14.2047 | 0.1293 | 5.1211 | -0.5309 | 16.5667 | 9.5587 | -4.0197 | 43.0676 |

| 10.9981 | 2.0416 | 14.1732 | 0.1303 | 5.2101 | -0.5646 | 16.5345 | 9.5681 | -4.0168 | 43.0765 |

| 14.9882 | 1.9933 | 14.0338 | 0.1234 | 5.7804 | -0.6630 | 16.5025 | 9.5546 | -4.0196 | 43.3054 |

| 19.9823 | 1.9503 | 13.7783 | 0.1167 | 6.7528 | -0.8532 | 16.3959 | 9.5868 | -4.0025 | 43.7251 |

| 24.9750 | 1.8946 | 13.5212 | 0.1093 | 8.0679 | -1.0560 | 16.3010 | 9.5992 | -3.9870 | 44.4502 |

| 29.9682 | 1.8405 | 13.2856 | 0.1008 | 9.7030 | -1.2702 | 16.2010 | 9.5904 | -3.9769 | 45.4742 |

| 34.9612 | 1.7775 | 13.0668 | 0.0928 | 11.6370 | -1.5025 | 16.0917 | 9.5785 | -3.9648 | 46.7771 |

| 39.9557 | 1.7189 | 12.8325 | 0.0888 | 13.8075 | -1.7476 | 15.9760 | 9.5792 | -3.9438 | 48.3114 |

| 49.9447 | 1.6341 | 12.5439 | 0.0781 | 18.8069 | -2.1966 | 15.7286 | 9.5084 | -3.9242 | 52.1792 |

| 59.9376 | 1.5568 | 12.3259 | 0.0718 | 24.3715 | -2.5761 | 15.5161 | 9.4125 | -3.9043 | 56.7741 |

| 69.9368 | 1.5092 | 12.1189 | 0.0805 | 30.0736 | -2.8653 | 15.3389 | 9.2762 | -3.8766 | 61.6555 |

| 79.9442 | 1.4805 | 11.9297 | 0.1015 | 35.4019 | -3.0609 | 15.2367 | 9.0469 | -3.8386 | 66.2977 |

| 89.9580 | 1.4749 | 12.2839 | 0.1287 | 39.4947 | -3.1439 | 15.1958 | 8.5655 | -3.8124 | 70.1872 |

| 99.9744 | 1.4832 | 13.1255 | 0.1581 | 41.9835 | -3.1293 | 15.2448 | 7.8486 | -3.8154 | 72.8993 |

| 109.9858 | 1.4987 | 14.7721 | 0.1832 | 42.4103 | -2.9744 | 15.3620 | 7.0311 | -3.8469 | 74.4362 |

| 119.9932 | 1.5589 | 16.4413 | 0.2069 | 41.6952 | -2.8156 | 15.5061 | 6.4084 | -3.8334 | 75.1679 |

| 129.9919 | 1.6386 | 18.4023 | 0.2285 | 40.1342 | -2.4345 | 15.7155 | 5.8288 | -3.8526 | 75.6608 |

| 139.9874 | 1.7686 | 19.9062 | 0.2549 | 38.7390 | -2.2418 | 15.9603 | 5.5951 | -3.6944 | 76.2879 |

| 149.9746 | 1.9332 | 19.7642 | 0.2115 | 37.1515 | -2.1168 | 16.2662 | 6.2616 | -2.5612 | 76.9102 |

| 159.9575 | 2.1190 | 22.3227 | 0.2072 | 36.3374 | -1.5500 | 16.7446 | 5.9812 | -2.6295 | 79.5324 |

| 169.9384 | 2.3736 | 24.8617 | 0.2048 | 36.7749 | -0.9786 | 17.2774 | 5.8048 | -2.7586 | 83.5601 |

| 179.9418 | 2.6574 | 27.6648 | 0.1862 | 38.3687 | -0.2019 | 17.9079 | 5.6176 | -2.8803 | 89.3202 |

In the case of the MM2 model, the lowest energy conformation is found with a dihedral angle of around 10o above the plane of the pyridinium ring. Attempting to include the MeMgI component in the calculations gave the message that Mg was not a recognised atom type.

As the MM2 molecular mechanic approach is known to encounter difficulties when dealing with compounds containing a positively charged nitrogen atom, the structure of compound 5 was also optimised using MMFF94 and MOPAC PM6 methods. These results showed higher overall energies for the ‘lowest energy’ conformations, though the dihedral angles obtained of 20.15o and 20.60o, respectively, are in good agreement with each other. Again, these show the lowest energy conformation as having the carbonyl group above the plane of the ring, which reinforces the chelation control mechanism proposed to account for the regiochemistry of the product.

| Method | Dihedral angle | Energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| MMFF94 | 20.1517o | 57.5375 |

| MOPAC PM6 | 20.6034o | 93.9079 (heat of formation) |

In a similar reaction, compound 7 can react with aniline to give compound 8, shown below, with its absolute stereochemistry defined:

This reaction involves the nucleophilic attack of an aniline on a quinolinium ring of compound 7 to form the product, compound 8. The product is an example of a nucleophile transferring agent – in this specific example it will act as an amine transferring reagent. Compound 7 is an NAD+ analogue, and displays similar activity to NAD+, which can act as a hydride transfer reagent, undergoing successive reductions and oxidations within the body.

Compound 7 can undergo nucleophilic addition, in a so-called anchoring step, followed by a releasing step in which the amine functionality is transferred to an electrophile[3].

In this example, the 1,4-product is the only one which can form – formation of a 1,2-adduct is prevented by the quinoline, rather than pyridine, ring within the structure, as this means that all the ortho and meta positions relative to the quinolinium nitrogen are not available for nucleophilic addition.

MM2 analysis of the dihedral angles for the carbonyl group within compound 7 show that the molecule has a lower energy when the carbonyl group is below the plane of the pyridinium ring (i.e. a negative dihedral angle). MM2 reports the lowest energy conformation to have a dihedral angle of around -19o.

| Dihedral angle (o) | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Charge/Dipole | Dipole/Dipole | Total energy |

| -1.0316 | 4.1803 | 13.4480 | 0.4372 | 8.8190 | 4.9100 | 29.6782 | 9.1753 | -4.8818 | 65.7662 |

| -2.0292 | 4.1800 | 13.3306 | 0.4371 | 8.7772 | 4.8539 | 29.6479 | 9.1673 | -4.8798 | 65.5141 |

| -3.0266 | 4.1226 | 13.2281 | 0.4315 | 8.7076 | 4.8191 | 29.6511 | 9.1654 | -4.8839 | 65.2416 |

| -4.0237 | 4.1422 | 13.0869 | 0.4317 | 8.6760 | 4.8017 | 29.6254 | 9.1560 | -4.8856 | 65.0343 |

| -5.0230 | 4.1177 | 13.0006 | 0.4305 | 8.6695 | 4.7323 | 29.6017 | 9.1561 | -4.8841 | 64.8244 |

| -6.0207 | 4.1328 | 12.8673 | 0.4293 | 8.6313 | 4.7114 | 29.5693 | 9.1540 | -4.8833 | 64.6120 |

| -7.0198 | 4.0812 | 12.7691 | 0.4262 | 8.6145 | 4.6868 | 29.5709 | 9.1564 | -4.8879 | 64.4172 |

| -8.0186 | 4.0942 | 12.6970 | 0.4264 | 8.6089 | 4.6380 | 29.5327 | 9.1440 | -4.8846 | 64.2568 |

| -9.0155 | 4.0923 | 12.5942 | 0.4248 | 8.6396 | 4.6048 | 29.5195 | 9.1303 | -4.8844 | 64.1212 |

| -10.0137 | 4.0467 | 12.5216 | 0.4231 | 8.7003 | 4.5477 | 29.5116 | 9.1281 | -4.8869 | 63.9921 |

| -11.0118 | 4.0454 | 12.4083 | 0.4200 | 8.7343 | 4.5266 | 29.4956 | 9.1234 | -4.8875 | 63.8660 |

| -15.0051 | 3.9701 | 12.0921 | 0.4151 | 9.1551 | 4.3012 | 29.4290 | 9.0783 | -4.8836 | 63.5573 |

| -19.9971 | 3.8981 | 11.7388 | 0.4043 | 9.8224 | 4.0685 | 29.3491 | 9.0205 | -4.8829 | 63.4190 |

| -21.6433 | 3.8504 | 11.4542 | 0.3944 | 10.6339 | 3.7230 | 29.3828 | 9.0206 | -4.8805 | 63.5788 |

| -24.9875 | 3.8353 | 11.3961 | 0.3923 | 10.9595 | 3.7591 | 29.2495 | 8.9400 | -4.8775 | 63.6543 |

| -29.9810 | 3.7886 | 11.1505 | 0.3784 | 12.1736 | 3.4805 | 29.1488 | 8.8533 | -4.8749 | 64.0988 |

| -34.9743 | 3.7065 | 10.9511 | 0.3663 | 13.7193 | 3.1622 | 29.0549 | 8.7532 | -4.8711 | 64.8424 |

| -39.9690 | 3.6352 | 10.7020 | 0.3497 | 15.5270 | 2.8066 | 28.9368 | 8.6451 | -4.8686 | 65.7337 |

| -49.9559 | 3.5231 | 10.5153 | 0.3227 | 19.9870 | 2.0170 | 28.7055 | 8.3624 | -4.8531 | 68.5799 |

| -54.9479 | 3.4599 | 10.4608 | 0.2990 | 24.8657 | 1.3163 | 28.4715 | 8.0263 | -4.8418 | 72.0576 |

| -69.9497 | 3.4621 | 10.2929 | 0.2822 | 29.8175 | 0.5671 | 28.3080 | 7.5670 | -4.8307 | 75.4661 |

| -79.9567 | 3.4823 | 10.5690 | 0.2764 | 34.1427 | 0.1441 | 28.2985 | 6.9293 | -4.8063 | 79.0360 |

| -89.9670 | 3.5577 | 11.3386 | 0.2779 | 37.0266 | -0.0663 | 28.4518 | 6.1157 | -4.7749 | 81.9271 |

| -99.9872 | 3.6146 | 12.5310 | 0.2819 | 38.3370 | -0.0564 | 28.7148 | 5.2686 | -4.7326 | 83.9589 |

| -109.9860 | 3.7357 | 13.9722 | 0.2874 | 38.2054 | 0.0438 | 29.0063 | 4.5886 | -4.6931 | 85.1463 |

| -119.9888 | 3.8106 | 15.4952 | 0.2810 | 37.2680 | 0.3552 | 29.3040 | 4.1093 | -4.6501 | 85.9733 |

| -129.9845 | 3.9107 | 16.8002 | 0.2752 | 36.1815 | 0.6965 | 29.5332 | 3.9771 | -4.6058 | 86.7685 |

| -139.9755 | 4.0180 | 18.1844 | 0.2619 | 35.3203 | 1.1834 | 29.6876 | 3.9750 | -4.5585 | 88.0721 |

| -149.9606 | 4.1338 | 19.7727 | 0.2408 | 35.0478 | 1.8422 | 29.9257 | 4.0037 | -4.5334 | 90.4333 |

| -159.9358 | 4.3162 | 21.4642 | 0.2113 | 35.8478 | 2.6098 | 30.1827 | 4.0701 | -4.5131 | 94.1889 |

| -169.9182 | 4.5287 | 23.2341 | 0.1846 | 37.9895 | 3.4608 | 30.5238 | 4.1534 | -4.4942 | 99.5807 |

| -179.8925 | 4.7797 | 25.2432 | 0.134 | 41.7716 | 4.415 | 31.028 | 4.162 | -4.4857 | 107.0477 |

The equivalent conformations, with the carbonyl present above the plane of the quinolinium ring, were also analysed, giving the following results:

| Dihedral angle (o) | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-bend | Torsion | Non-1,4-VDW | 1,4 VDW | Charge/Dipole | Dipole/Dipole | Total energy |

| 0.9682 | 4.2343 | 13.5632 | 0.4315 | 9.1649 | 4.8470 | 29.6221 | 9.1807 | -4.8723 | 66.1714 |

| 1.9664 | 4.2777 | 13.6512 | 0.4326 | 9.1190 | 4.8740 | 29.6074 | 9.1921 | -4.8738 | 66.2802 |

| 2.9648 | 4.2571 | 13.8033 | 0.4299 | 9.2047 | 4.9003 | 29.6283 | 9.2007 | -4.8767 | 66.5476 |

| 3.9624 | 4.2691 | 13.9111 | 0.4329 | 9.3236 | 4.9245 | 29.6387 | 9.2026 | -4.8751 | 66.8276 |

| 4.9614 | 4.3057 | 14.0066 | 0.4351 | 9.4382 | 4.9506 | 29.6324 | 9.1925 | -4.8729 | 67.0881 |

| 5.9608 | 4.3143 | 14.0951 | 0.4337 | 9.5802 | 4.9364 | 29.6318 | 9.1929 | -4.8746 | 67.3098 |

| 6.9608 | 4.3241 | 14.1485 | 0.4306 | 9.7009 | 4.8965 | 29.6342 | 9.1784 | -4.8801 | 67.4332 |

| 7.9592 | 4.3385 | 14.2742 | 0.4283 | 9.8608 | 4.9060 | 29.6368 | 9.1785 | -4.8802 | 67.7429 |

| 8.9587 | 4.3627 | 14.3354 | 0.4278 | 10.0244 | 4.8787 | 29.6345 | 9.1647 | -4.8825 | 67.9458 |

| 9.9576 | 4.3620 | 14.4457 | 0.4261 | 10.2214 | 4.8639 | 29.6425 | 9.1585 | -4.8838 | 68.2363 |

| 10.9572 | 4.3584 | 14.5678 | 0.4249 | 10.4415 | 4.8361 | 29.6546 | 9.1506 | -4.8836 | 68.5503 |

| 14.9502 | 4.3983 | 14.9891 | 0.4221 | 11.4665 | 4.8207 | 29.6467 | 9.1281 | -4.8800 | 69.9915 |

| 19.9450 | 4.4221 | 15.4171 | 0.4078 | 13.1797 | 4.6270 | 29.6521 | 9.0513 | -4.8811 | 71.8760 |

| 21.5880 | 4.4369 | 15.4844 | 0.4037 | 13.8312 | 4.5318 | 29.6488 | 9.0125 | -4.8844 | 72.4649 |

| 24.9400 | 4.4311 | 15.8750 | 0.3959 | 15.1507 | 4.3973 | 29.6413 | 8.9700 | -4.8808 | 73.9805 |

| 23.9363 | 4.4409 | 16.2448 | 0.3783 | 17.4858 | 4.0936 | 29.6249 | 8.8457 | -4.8868 | 76.2272 |

| 34.9291 | 4.4287 | 16.8055 | 0.3633 | 19.9405 | 3.8345 | 29.5888 | 8.7486 | -4.8843 | 78.8256 |

| 39.9260 | 4.4317 | 17.2312 | 0.3452 | 22.7335 | 3.4898 | 29.5523 | 8.6013 | -4.8945 | 81.4906 |

| 49.9201 | 4.3668 | 18.2990 | 0.3163 | 28.7432 | 2.7903 | 29.4749 | 8.2673 | -4.9115 | 87.3462 |

| 59.9175 | 4.3304 | 19.5219 | 0.3001 | 35.0914 | 2.1611 | 29.3066 | 7.8692 | -4.9320 | 93.6487 |

| 69.9226 | 4.4112 | 20.3586 | 0.3004 | 41.5071 | 1.7453 | 29.0476 | 7.2943 | -4.9746 | 99.6898 |

| 79.9361 | 4.4035 | 21.3101 | 0.3123 | 47.3633 | 1.6589 | 28.7666 | 6.1904 | -5.0065 | 104.9986 |

| 90.0015 | 5.7659 | 22.2851 | 0.4388 | 45.3080 | 2.7541 | 29.1616 | 2.0121 | -4.9739 | 102.7517 |

| 99.9988 | 5.8965 | 24.8976 | 0.5025 | 42.3119 | 3.4430 | 29.6209 | 0.9010 | -5.0249 | 102.5485 |

| 109.9903 | 6.0422 | 27.2327 | 0.5511 | 39.5413 | 4.1556 | 30.1128 | 0.1387 | -5.0683 | 102.7060 |

| 119.9827 | 6.2249 | 29.0770 | 0.5896 | 37.0624 | 5.1015 | 30.5171 | -0.2117 | -5.0862 | 103.2746 |

| 129.9651 | 6.3804 | 31.3040 | 0.6052 | 35.2833 | 6.1119 | 31.0001 | -0.4694 | -5.1101 | 105.1055 |

| 139.9524 | 6.5049 | 32.1586 | 0.5996 | 35.6591 | 7.0826 | 31.1454 | -0.5003 | -5.0870 | 107.5628 |

| 149.9361 | 6.5914 | 33.3918 | 0.5803 | 37.1993 | 8.0429 | 31.5653 | -0.6443 | -5.0832 | 111.6434 |

| 159.9410 | 6.6978 | 29.5840 | 0.6030 | 39.7688 | 5.7727 | 30.7503 | 0.3657 | -4.9546 | 108.5878 |

| 169.9198 | 6.8073 | 30.8237 | 0.5756 | 42.7135 | 6.6140 | 31.1868 | 0.3128 | -4.9643 | 114.0694 |

| 179.9083 | 6.6057 | 30.9359 | 0.5183 | 49.6782 | 6.2877 | 31.5631 | -0.1317 | -4.9683 | 120.4889 |

This shows that, for a given positive and negative dihedral angle, the lower energy conformation is that with a negative dihedral angle, with the carbonyl group below the plane of the quinolinium ring.

This can be compared to the results from MMFF94 and PM6 MOPAC analyses, which report a dihedral angle of around 40o below the plane of the quinolinium ring. These results are markedly different from those obtained using the MM2 analysis, which found an optimal dihedral angle of -19o. Again, the MM2 results are not particularly accurate due to the inability to process the N+ of the ring. The MMFF94 and PM6 results are generally in good agreement:

| Method | Dihedral angle | Energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| MMFF94 | -40.4213o | 99.6385 |

| MOPAC PM6 | -43.3294o | 156.1984 (heat of formation) |

(NB. Unlike the MM2 force field, the MMFF94 force field does not permit a dihedral angle to be specified, in order to calculate the energy of such a geometry.)

This shows that the carbonyl group is located below the plane of the quinolinium ring. In the product, the NHPh group is therefore located anti to the carbonyl group, meaning it adds on the opposite face to the carbonyl group. This is assumed to be because of a steric influence exerted by the lactam carbonyl group, preventing attack from the lower face of the molecule and therefore promoting attack from the top face of the molecule. As the aniline is not an organometallic reagent, no chelation control is possible, meaning the reactivity is the opposite of what would presumably be observed with a Grignard reagent, i.e. in the transformation of compound 5 to compound 6.

The main factor in determining the diastereoselectivity of compound 8 has been proposed to be the following C-C(=O) axis[3]:

The axis is presumed to have a key role during the anchoring step, in which the NHPh group adds to the ring. The orientation of said axis can be controlled by the presence of a chiral inducer – in this case, this is the methyl group on the carbon adjacent to the lactam nitrogen. The carbonyl group then adopts a conformation anti to this methyl group.

One application for the product, compound 8, is for the atropenantioselectively amination of aromatic esters[3].

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

A key intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol, an anticancer drug, can exist as a pair of atropisomeric compounds, shown below:

Compounds 9 and 10 exist as atropisomers. Atropisomers are defined as stereoisomers with hindered rotation about a single bond. This bond rotation energy is high enough for the two isomers to be isolated as separate conformers. In this example, the carbonyl group can point either up (i.e. proximal to the bridging carbon), or down (i.e. distal to the bridging carbon).

Performing an MM2 energy minimisation of the atropisomers 9 and 10 reveals that compound 10 is around 15 kcal mol-1 more stable than compound 9, meaning that the compound is most stable with the carbonyl group pointing downwards.

| Energy parameter | Compound 9 energy (kcal mol-1) | Compound 10 energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 3.3202 | 2.5502 |

| Bend | 20.1512 | 10.7038 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.4746 | 0.3241 |

| Torsion | 21.8793 | 19.5871 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -0.4721 | -1.2364 |

| 1,4 VDW | 14.5351 | 12.5552 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -0.0061 | -0.1828 |

| Total energy | 59.8823 | 44.3013 |

This may be due to decreased steric repulsion between the carbonyl group and the bridging methylene carbon in the downwards atropisomer, compared to the isomer with the carbonyl group pointing upwards.

Performing an energy minimisation with the MMFF94 force field produced the same overall conclusion, though the energies of the two compounds were significantly higher than those found with the MM2 force field:

| Compound 9 energy (kcal mol-1) | Compound 10 energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|

| 82.7069 | 60.5859 |

This may be due to different parameters being used in the MMFF94 force field – generally, energies obtained from different force fields cannot be directly compared. In this case, the overall trend is the same – i.e. the isomer with the carbonyl group pointing downwards is the most stable.

Paquette[4]synthesised this taxol intermediate using an atropselective anionic oxy-Cope rearrangement. Cope rearrangements tend to be reversible reactions, but in this case, the strong C=O bond renders the reaction generally irreversible.

The carbonyl group stereochemistry following the ring-closing Cope rearrangement has been found to vary depending on the size of substituents present on the 6-membered ring. In this case, the ring is unsubstituted.

Paquette found that bulky axial substituents (ie OTBS groups) below the ring will lead to the carbonyl group favouring the upwards direction, whereas for the unsubstituted ring, the carbonyl group will tend to prefer the downwards direction.

It has been found that an endo-chair transition state is involved in the formation of the taxol intermediate[4]. This conformation for the transition state has been attributed to favourable orbital alignment and favourable distance between the bonds involved in the sigmatropic rearrangement. This means that initially, the carbonyl group will be formed facing upwards, i.e. proximal to the methylene bridging carbon.

This contrasts to the results found using the MM2 and MMFF94 calculations, which show that atropisomer 10 is of lower energy.

Provided sufficient thermal energy is available, sigma bond rotations can occur to isomerise compound 9 to compound 10. The resulting structure has a lower energy framework and thus the reaction will significantly favour the downwards facing carbonyl group.

On a similar note, research has found that the double bond present undergoes abnormally slow functionalisation. The alkene can be considered as a hyperstable alkene.

Compounds 9 and 10 contradict Bredt’s 1924 rule for alkenes, which stated that double bonds tend to avoid being found next to ring junctions[5]. Since then, numerous bridgehead alkenes have been documented in literature, and MM2 calculations have found that roofed ring systems with trans double bonds can be considered as hyperstable alkenes[6].

Maier and Schleyer[6] proposed that hyperstable alkenes tend to show less strain than the hydrogenated parent hydrocarbon. Wiseman[5] found that all previously isolated bridgehead alkenes have been present as a trans cycloalkene moiety, with at least 8 carbons present in the ring. In this case, the two atropisomers can be defined as anti-Bredt olefins, in which the double bond is present in a medium ring of 10 atoms. They can therefore show a strong resistance to hydrogenation.

The energy difference between a bridgehead alkene and its corresponding parent hydrocarbon can be defined as the olefin strain energy. This can be correlated to the heats of hydrogenation of the alkene compounds.

Maier and Schleyer formulated some empirical rules for determining the stability of bridgehead alkenes, based on their energy difference from the parent hydrogenated hydrocarbon.

These rules can be defined as follows[5]:

· 1. For isolable bridgehead olefins, the olefin strain energy must be less than or equal to 17 kcal mol-1.

· 2. For observable bridgehead olefins, the olefin strain energy must be between 17 and 21 kcal mol-1.

· 3. For unstable bridgehead olefins, the olefin strain energy must be above 21 kcal mol-1.

According to the MM2 manual[7], the strain energy for a compound can be obtained by summing the contributions from bonding interactions within a compound: these include stretches, bends and torsional strain.

This means that the olefin energy of compounds 9 and 10 can be calculated by comparing the bonding interaction energies with those of the fully hydrogenated parent hydrocarbons, which have had their energy minimised with the MM2 force field.

| Energy parameter | Hydrogenated compound 9 energy (kcal mol-1) | Hydrogenated compound 10 energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 4.4725 | 4.9077 |

| Bend | 22.2708 | 22.2217 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.9328 | 1.0742 |

| Torsion | 25.3102 | 22.6433 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | 2.2834 | 4.1803 |

| 1,4 VDW | 18.4736 | 17.9341 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Total energy | 73.7432 | 72.9614 |

This gives the following results:

Compound 9: total strain energy = 45.8253 kcal mol-1

Hydrogenated version of compound 9: total strain energy = 52.9863 kcal mol-1

The strain energy for compound 9 can then be calculated to be 52.9863 – 45.8253 = 7.1610 kcal mol-1.

Similarly, for compound 10: total strain energy = 33.1652 kcal mol-1

Hydrogenated version of compound 10: total strain energy = 50.8469 kcal mol-1

Overall olefin strain energy: 50.8469 – 33.1652 = 17.6817 kcal mol-1.

This means that compound 9 would be classed as isolable by Maier and Schleyer’s rules, and compound 10 as observable. This helps to account for why the two compounds can interconvert following synthesis – they are both highly stable bridgehead olefins which are favoured by the empirical rules.

Calculating the energies using the MMFF94 force field gives the following results:

| Hydrogenated compound 9 energy (kcal mol-1) | Hydrogenated compound 10 energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|

| 110.372 | 110.342 |

Unfortunately the MMFF94 method does not separate out energy terms, meaning that the olefin strain energy cannot be calculated from this method's results.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

The above structural analyses involved an entirely molecular mechanical treatment. This was shown to be insufficient, particularly in the case of cyclopentadiene, whose formation invoking an endo stereoselectivity involved secondary orbital interactions not accounted for in the molecular mechanics model. The following analyses aim to delve into these electronic factors which influence activity, particularly in terms of how electrons can influence both bond parameters and spectroscopic results.

In this section, the effect that orbitals exert on regioselectivity will be examined.

Compound 12 is a diene, which can potentially react with electrophiles such as dichlorocarbene and peracids (e.g. mCPBA) at the double bond syn or anti to the C-Cl bond.

Compound 12 can be synthesised in the following manner[8]:

It has been found[8] that compound 12 displays excellent selectivity for electrophilic addition at one of the two double bonds in particular. This is due to a lowering of electron density in the double bond anti to the chloro substituent, resulting in electrophilic addition occurring at the double bond syn to the chloro substituent.

In order to account for these experimental observations, the geometry of compound 12 was predicted by optimising the geometry using the MM2 method. Following this, the energies of the frontier orbitals were predicted with the MOPAC PM6 application.

This gave the following orbital electron density distributions:

| Molecular orbital | Electron density distribution |

|---|---|

| HOMO-1 |  |

| HOMO |  |

| LUMO |  |

| LUMO+1 |  |

The structure of compound 12 is based on an extremely rigid carbon skeleton, and there is almost negligible steric distinction between the two potential sites for electrophilic attack. This means that the regioselectivity seen could be as a result of either orbital, electrostatic or transition-state mediated factors[9].

X-ray analysis[9] of the crystal structure of compound 12 has revealed substantial geometric distortion is present within the structure: the distance of each of the carbons forming the C=C bond anti to the chloro substituent is 0.24 Å closer to the bridgehead carbon than those forming the syn double bond. This result does now suggest a degree of steric differentiation between the two sites.

A proposed explanation for the observed distortion, and the regioselectivity seen, comes from Rzepa[9], who proposed a stabilising antiperiplanar interaction between the C-Cl σ* orbital, and the π orbital of the anti double bond. This would, in turn, result in the syn double bond gaining a higher nucleophilicity, meaning that it would be more susceptible to nucleophilic attack.

Analysis of the orbital electron density diagrams produced seems to support these ideas. The HOMO shows a high region of π electron density at the double bond syn to the chloro substituent, making it the best candidate for electrophilic attack. The HOMO-1 corresponds to the anti double bond’s π orbital. The HOMO-1 is ideally set up for antiperiplanar overlap with the C-Cl σ* orbital, which is found in the LUMO+2.

The vibrational frequencies of compounds 12 and 13 were also compared using a B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian calculation, to determine the effect of the C-Cl bond. This gave the following results:

| Compound | C-Cl stretching frequency (cm-1) | C=C stretching frequency/frequencies (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

|

| |

|

|

The results show a marked decrease in the C-Cl stretching frequency in compound 12, the diene, compared to compound 13, the monoalkene. This can be rationalised by taking the aforementioned principles into account: interaction of the anti π bond with the C-Cl σ* orbital will act to lower the C-Cl bond order, resulting in a weaker bond with a lower vibrational frequency. Consequently, this will also result in a reduction of electron density in the anti π bond, which again can be seen as a reduction in vibrational frequency relative to the frequency seen for the syn double bond.

The vibrational frequency of the syn double bond differs little between the two compounds, confirming that this is relatively unaffected by the chloro substituent.

Structure based mini project: Highly selective cobalt-mediated [6+2] cycloaddition of cycloheptatriene and allenes

Introduction

The synthesis of eight-membered carbocycles has been widely researched, namely due to their profound biological importance. One such method of synthesis[12] is a chromium(0) catalysed [6π + 2π] cycloaddition between cycloheptatriene and an unsaturated compound (to act as the 2π electron component), to produce an 8-membered carbocycle with a bridging methylene unit.

If a substituted allene is used as the 2π electron component, it has been found that the product will form with exclusively E-selectivity of the allene-derived component[12]:

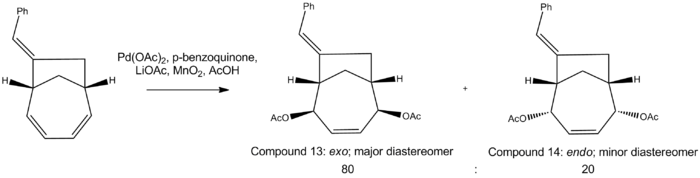

This stereoselective product can then undergo a palladium-catalysed 1,4-diacetoxylation across the conjugated diene functionality:

Extensive research[13] has found that palladium catalysts will promote solely cis-addition to 7-membered rings. Following addition of the first nucleophile, a (π-allyl)-Pd complex is formed, which acts to direct stabilised carbon nucleophiles (AcO- in this case) via an external trans attack to the 4-position, relative to the first nucleophile’s addition site.

This will generate an exo major diastereomer, with the acetoxy groups on the same side as the methylene bridge, and an endo minor diastereomer, with the acetoxy groups on the opposite face as the methylene bridge.

The aim of this section is to computationally analyse the minimum energies of both of the proposed major and minor diastereomers, and to calculate predicted IR and 13C NMR spectra to compare to the literature data, to determine if the authors’ assignments were correct.

The relative energies of the two diastereomers were calculated using the MM2 force field, which gave the following results:

| Energy parameter | Major diastereomer energy (compound 13) | Minor diastereomer energy (compound 14) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.6121 | 2.5720 |

| Bend | 17.8226 | 33.5554 |

| Stretch-bend | 0.6623 | 0.8237 |

| Torsion | -2.6756 | -2.7435 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -0.3604 | -1.8980 |

| 1,4 VDW | 21.4676 | 22.9560 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 10.3935 | 9.6495 |

| Total energy | 49.9222 | 64.9152 |

This shows that compound 13 is indeed lower in energy than compound 14. Assuming the reaction is under thermodynamic control, this would support the conclusion that the major diastereomer is compound 13.

13C NMR chemical shift calculation

The 13C NMR spectra of both the major and minor products were predicted using the GIAO approach. This involved minimising the energy of the two structures using the MM2 force field, and creating a Gaussian input file from the energy minimised structure. This was then submitted to be scanned using DFT=mpw1pw91, using a 6-31G(d,p) basis set, resulting in an optimised structure suitable for NMR predictions. The structures were again submitted to SCAN for NMR predictions, using chloroform as solvent as per the literature.

The GIAO approach is extremely sensitive to slight conformational changes. The compounds chosen for this analysis are rigid, bicyclic systems, which should act to minimise conformational flexibility.

To correct for a systematic error present for ester carbons, the chemical shifts of the two carbonyl ester carbons were corrected using the following equation: δcorr = 0.96δcalc + 12.2.

| Carbon number | Computed chemical shift δ/ppm | Literature chemical shift δ/ppm |

|---|---|---|

| 21 | 168.992 | 170.5 |

| 25 | 168.828 | 170.3 |

| 8 | 143.691 | 143.5 |

| 13 | 134.431 | |

| 4 | 130.09 | |

| 14 | 125.21 | 128.8 |

| 3 | 124.807 | 128.4 |

| 15 | 124.561 | 127.9 |

| 17 | 124.248 | 126.5 |

| 18 | 124.187 | 124.5 |

| 16 | 123.052 | |

| 10 | 121.937 | |

| 5 | 80.8626 | 75.2 |

| 2 | 79.7193 | 74.8 |

| 1 | 48.6333 | 49.0 |

| 6 | 42.2703 | 41.3 |

| 9 | 41.2247 | 34.6 |

| 7 | 30.3508 | 27.5 |

| 22 | 20.9424 | 21.5 |

| 26 | 20.7258 | 21.4 |

| Carbon number | Computed chemical shift δ/ppm | Literature chemical shift δ/ppm |

|---|---|---|

| 25 | 170.695 | 170.5 |

| 21 | 169.372 | 170.3 |

| 8 | 145.521 | 144.7 |

| 13 | 134.463 | 137.9 |

| 4 | 128.965 | 128.3 |

| 14 | 126.933 | 128.2 |

| 3 | 125.718 | 126.4 |

| 10 | 125.641 | |

| 15 | 124.688 | 124.9 |

| 17 | 124.378 | 123.7 |

| 18 | 122.918 | |

| 16 | 122.811 | |

| 2 | 80.8275 | 76.4 |

| 5 | 80.0229 | 74.3 |

| 1 | 47.5555 | 48.8 |

| 6 | 43.8084 | 40.6 |

| 9 | 35.9552 | 32.0 |

| 7 | 33.7674 | 28.9 |

| 26 | 22.9504 | 21.5 |

| 22 | 20.7164 | 21.4 |

The NMR results are in excellent agreement with those in the literature. All but one of the assignments are correct to within 5ppm, suggesting the conformations adopted are correct. As the chemical shift distribution of the two isomers is very similar, X-ray diffraction of the two diastereomers could be used to definitively determine which isomer is which. The paper’s authors did in fact perform an X-ray diffraction of the products, which confirmed that the exo product is the major diastereomer.

HRMS is commonly used to identify unknown products, though in this case it would be expected that the two diastereomers would fragment in almost identical fashions, meaning this technique would not be of use for these products.

Predicted IR spectrum

The IR spectra of the two diastereomers was predicted using DFT=B3LYP, and the 6-31G(d,p) basis set. Using Guassview to analyse the scan results, ‘normal modes’ were saved, before analysing these and their predicted intensities.

Only absorptions with intensities greater than 50 were selected for characterisation.

| Computed vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Assignment |

|---|---|

| 1014.86 | C-H bend |

| 1039.14 | C-O stretch |

| 1228 to 1265 | C-C bends |

| 1404.37 | C-H stretch |

| 1847.06 | C=O stretch (antisymmetric) |

| 1850.96 | C=O stretch (symmetric) |

| Computed vibrational frequency (cm-1) | Assignment |

|---|---|

| 1006.16 | C-H bend |

| 1065.46 | C-O stretch |

| 1215.54 | C-H bend |

| 1221.88 | C-C stretch |

| 1263 | CH (methyl) |

| 1407.20 | C-H stretch |

| 1838.91 | C=O stretch (antisymmetric) |

| 1849.47 | C=O stretch (symmetric) |

The predicted IR spectra show slightly different absorption regions for the most strongly absorbing bands, though as the same functionalities are present within each compound, this analytical technique would prove insufficient in assigning the two diastereomers.

References

- ↑ N. L. Allinger, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1977, 99, 8127-8134.DOI:10.1021/ja00467a001

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838-841. DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ref 1 proline" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 S. Leleu, C. Papamicael, F. Marsais, G. Dupas, V. Levacher, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928.DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "proline ref 2" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 4.0 4.1 L. A. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard and R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277-283.DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "taxol ref 5" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 W. F. Maier and P. v. R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891-1900.DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "hyperstable alkenes ref 2" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 6.0 6.1 S. Lalitha, J. Chandrasakhar and G. Mehta, Tet. Lett., 1990, 31, 4219-4222.DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)97586-5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "hyperstable alkenes ref 1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ MM2 help section within ChemBio3D: strain is defined on the page describing 'force fields'.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 B. Halton and S. G. G. Russell, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 5553-5556.DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "dcc ref 2" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447.DOI:10.1039/P29920000447 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "dcc ref 1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ SPECTRa Chemical Depository: Compound 12DOI:10042/to-6472

- ↑ SPECTRa Chemical Depository: Compound 13DOI:10042/to-6471

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 H. Clavier, K. L. Jeune, I. Riggi, A. Tenaglia and G. Buono, Org. Lett., 2011, 13, 308-311.DOI:10.1021.ol102783x Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "best mini project ref" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ J-E. Backvall, S. E. Bystrom and R. E. Nordberg, J. Org. Chem., 1984, 49, 4619-4631DOI:10.1021/jo00198a010

- ↑ SPECTRa Chemical Depository: Compound 13a DOI:10042/to-6424

- ↑ SPECTRa Chemical Depository: Compound 14 DOI:10042/to-6425

- ↑ SPECTRa Chemical Depository: Compound 13a DOI:10042/to-6449

- ↑ SPECTRa Chemical Depository: Compound 14 DOI:10042/to-6450