Rep:Mod:happychicken

Transition States and Reactivity

Introduction

Pericyclic Reactions

The reactions studied in this experiment are a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement (the Cope rearrangement) and Diels Alder cycloadditions which are both classes of pericyclic reaction. Their reactivity can be predicted by the Woodward-Hoffmann rules, which state:

The total number of (4q+2)s and (4r)a components of a thermal pericyclic reaction must be odd.[1]

These rules apply when considering thermal reactions. Photochemical reactions have different Woodward Hoffman rules and are not considered in this experiment. The symbols 'q' and 'r' can be any integer (but not zero) so that each component represents an orbital system on the molecule which is reacting. For example; a 6π orbital system with suffix 's' reacting with a 2π orbital system, also with suffix 's', has one componant (6π) which satisfies the (4q+2)s requirement and no components which satisfy (4r)a. The 's' and 'a' subscripts/suffixes stand for 'suprafacial' and 'antarafacial'. A suprafacial component reacts to form bonds from the same face of the orbital, whereas an antarafacial component forms bonds from opposite faces of the orbital. This analysis is applied when a Woodward Hoffman diagram, demonstrating the reacting orbital fragments, is drawn to determine in which configuration a molecule will react, and it known as Frontier Molecular Orbital Theory.

A concerted pericyclic reaction must conserve orbital symmetry. Orbital symmetry is defined by the symmetry of an orbital with respect to a plane parallel to the highest axis of rotation of the molecule. This plane must also be a mirror plane of the molecule. If the phase of the orbitals is opposite on either side of the plane, the orbital is considered to be antisymmetric (AS) and if the orbital is symmetric with respect to the plane, then it is labelled at symmetric (S). Orbital symmetry is conserved in a reaction when, for example, an AS orbital from one fragment and a S orbital from another fragment combine to create two new orbitals, one AS and the other S.

The ‘endo rule’, referring to Diels Alder reactions, is where the exo product is kinetically favoured and the endo product is thermodynamically favoured.[4]

This experiment explores the reasons behind this rule by by examining the secondary orbital effect using different levels of computational theory on GAUSSIAN 09W[5] to generate the orbitals. The secondary orbital effect is when non-active orbitals overlap with an overall stabilising effect, the active orbitals being those involved in the formation and breaking of bonds.[6]

Computational Methods

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a quantum mechanical modelling method for solving the Schrödinger equation. It is a very widely used computational technique because of its relative cheapness. DFT describes the ground state energy as a function of electron density (hence the name density functional theory), as there is a strong correlation between the ground state wavefunction and the ground state electron density.[7] The Hartree Fock (HF) method is an example of DFT. The Hartree-Fock approximation is a method of solving the Schrödinger equation by forming a linear combination of Hartree products, which can be written as a Slater determinant, to satisfy the rule that an electron wavefunction must be antisymmetric with respect to electron exchange; one Hartree product would not satisfy this condition. A Hartree product is a combination of one-electron orbitals where antisymmetry and electron spin are disregarded.[8] In Gaussian, HF is a cheap method to accurately generate the molecular orbitals for a molecule under study. Another example of DFT is B3LYP. B3LYP is an 'exchange functional' combined from three different parameters, and is an accurate way to calculate the energy of molecule.[9]

Gaussian allows calculations to be carried out using a variety of basis sets. The two main basis sets used in these experiments are 3-21G and 6-31G* (6-31G(d) is the equivalent in GausView[5]). They are 'split-valence' basis sets, meaning that there is more than one basis function making up each valence orbital. The nomenclature for these basis sets was defined by John Pople, who generalised the notation to X-YZG. 'X' defines the number of Gaussian 'bell' functions which make up the core atomic orbital basis function, and 'Y' and Z' mean that two basis functions make up each of the valence orbitals (split-valence basis set), where the numbers in place of Y and Z represent how many Gaussian functions are in the linear combination for each basis function.[10] The * after the 6-31G* basis set means that the calculation adds extra orbitals to allow for polarisation in the calculation molecular orbitals.

Austin Model 1 (AM1) is a semi empirical computational method used for its cheapness. It is a simplification of the Hartree-Fock method; the overlap integral (S) is assumed to be 1, so the Hartree-Fock secular equation becomes |H-E|=0 from |H-SE|=0.[11]

All computational calculations in the following experiments have been carried out using GAUSSIAN 09W.[5]

Nf710 (talk) 13:28, 5 November 2015 (UTC)Very good understanding of the principles behind computational chemistry

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

Optimisation of Reactants and Products

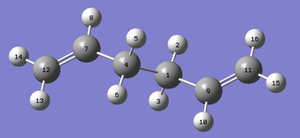

The 1,5-Hexadiene structure was optimised in three different configurations around the central four carbon atoms using the Hartree-Fock method with a 3-21G basis set.

#p HF/3-21G opt geom=connectivity

route card (1)

The keyword 'opt' tells Gaussian to optimise the given geometry to a minimum; it does this by moving along the simulated potential energy surface in the direction of the steepest negative gradient until the second derivative becomes zero; the minimum. The keyword 'geom=connectivity' tells Gaussian to read the geometry from the input file based on the connectivity syntax. The initial molecule optimised (molecule 1) was a general antiperiplanar configuration; meaning the two ethylene groups were at 180° (but the rest of the molecule's orientation was not specified) to each other when viewed as a Newman projection. Molecule 2 was optimised in a gauche configuration, meaning the two ethylene groups were now 60°. The energy for this configuration was expected to be higher because of steric overlap and torsional strain around the central C-C bond, raising the molecule's overall potential energy. Both these optimised molecules had the same symmetry; point group C2 without any relaxation of symmetry required. A prediction could be made that the antiperplanar configuration is the most stable and the ethylene groups being parallel would maximise stabilisation from π bond overlap. Following this prediction, molecule 3 was also optimised in the anitperiplanar configuration with the π bonds approximately parallel.

Comparing to Appendix 1 in the wiki script[12], molecule 1 in the antiperiplanar configuration can be identified as ‘anti 1’, molecule 2 in the gauche conformation as ‘gauche 4’ and the final predicted molecule 3 as ‘anti 2’. The molecules were identified by comparisons of energies and point groups, all of which correspond correctly.

Nf710 (talk) 13:35, 5 November 2015 (UTC) if you look in the appendix of the wiki, it clearly says gauche3 is the lowest in energy this is because of secondary orbital interactions between the two pi-bonds which are actually closer to each other but because of the twist are actually in phase in the homo and actually interact favourably. If you look in the .chk and look at the orbitals you can see that.

| Matching molecule from the wiki script[12] | Configuration | Molecule | Energy/ Hartrees | Point Group | Optimisation log file link | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule 1 | anti 1 | Antiperiplanar |

|

-231.69260235 | C2 | here | |||

| Molecule 2 | gauche 4 | Gauche |

|

-231.69153032 | C2 | here | |||

| Molecule 3 | anti 2 | Antiperiplanar |

|

-231.69253 | Ci | here |

Molecule 3 is not the absolute lowest energy conformation as molecule 1 had a lower energy, but the energies are the same to three significant figures, meaning there is no significant difference between them.

Molecule 3 was re-optimised using the B3LYP method with a 6-31G* basis set. The log file can be found here.

#p B3LYP/6-31G* opt geom=connectivity

route card (2)

The energy when optimised was calculated as -234.61171035 Hartrees, which is slightly higher than the structure optimised with the lower basis set. In a larger basis set, more orbitals are included in the analysis and therefore the overall energy is increased by a higher potential energy from orbital repulsion. The point group remained as Ci. The structure optimised with the higher basis set has altered slightly, as the bond lengths around the C=C double bonds have got slightly longer (~0.01 angstroms) and the bonds around the central carbon atoms have got slightly shorter. The angle of the double bond and its adjacent carbon has also got slightly larger. This change is only by ~0.4 degrees so may not be considered to be significant. A frequency calculation was then carried out to determine if the structure found was at a minimum on the potential energy surface; characterised by the frequencies being all real or positive. The log file of the calculation can be found

Nf710 (talk) 13:40, 5 November 2015 (UTC) You haven't done this in enough detail, you should have presented all the bond angles in a table.

here.

#p B3LYP/6-31G* freq geom=connectivity

route card (3)

The keyword 'freq' tells Gaussian to calculate all the possible frequencies of the bonds in the molecule. It does this by calculating the force constants of all the bonds in the molecule to a converged value and using the equation (where m is the reduced mass,f is the frequency and k is the force constant)[13], assuming each bond is a perfect harmonic oscillator, to relate them to a frequency.

All frequencies calculated were positive, and therefore real, meaning the structure is at an energy minimum in the potential surface; the minimum two frequencies were 74.29 cm-1 and 81.00 cm-1.

Nf710 (talk) 13:44, 5 November 2015 (UTC) Very good understanding of how the force constant relate to frequency, but you haven't put down any of the thermochemistry

Optimising the ‘chair’ and ‘boat’ Transition Structures

Optimising the 'chair' Structure

Using route card 1, an allyl fragment (CH3CHCH2) was optimised, the log file of which can be found here. A ‘chair’ transition structure was then optimised using two of the optimised allyl fragments positioned with the terminal carbons approximated at 2.2 angstroms apart using two different methods. Optimisation 1 involved using the keyword opt=noeigen in the route card to prevent the calculation from producing an error when it encounters a negative frequency. The log file can be found here.

#p HF/3-21G freq opt=(calcfc,ts,noeigen) geom=connectivity

route card (4)

This optimisation shortens the distance between the terminal carbons from 2.2 Å to 2.05 Å. A negative frequency of -818 cm-1 was produced which corresponds to the Cope rearrangement. [See figure 2 in Appendix 1]. The negative frequency is an imaginary frequency derived from a negative force constant (using the perfect harmonic oscillator equation defined in the previous section). Gaussian will find a negative frequency when the molecule is optimised to a transition state, or a saddle point on the potential energy surface. A saddle point is where, along one coordinate of the surface, the structure is a maximum and along another coordinate it is a minimum, much like the shape of a saddle. Optimisation 2 involved using the ModRedundant tool to freeze the distances between the terminal carbons can be frozen at 2.2 Å, and then optimising the structure. This only reaches the correct optimisation if the input syntax is: B 6 11 2.2 B / B 6 11 F. The numbers quoted are the numbers of the terminal carbons labelled by Gaussian. The ModRedundant line is incorporated into the route card by incorporation into the opt keyword. The structure was optimised to a minimum, the log file of which can be found here.

#p hf/3-21g opt=modredundant geom=connectivity

route card (5)

The ModRedundant tool allows the creation of bonds which the GaussView[5] input syntax does not automatically create. Because Gaussian does not physically register any interaction between the terminal carbons, these interactions must be manually created.

To optimise the bond distances, the structure was then optimised to a transition state by adding the key words opt=calcfc (calculate the force constants once) and opt=ts (optimise to a transition state) to route card (5). The log file can be found here. Although the script specifies that the force constants should never be calculated in this optimisation, the calculation failed unless force constant calculations were specified. Comparing the optimised bond lengths to those from optimisation 1; 2.02018 Å and 2.02026 Å, the bond lengths in optimisation 2 are equal; 2.02064 Å, unlike in optimisation 1, but are longer than those in optimisation 1. However both optimisations give the same bond lengths to within 4 significant figures, so it can be assumed no significant change takes place. Both optimisations also give one imaginary frequency of about -818 cm-1, and so it can be assumed that both methods produce a very structurally similar transition state. Both frequencies are antisymmetric, as they refer to the breaking of one bond and the forming of another [see figures 2 and 3 from Appendix 1]. Gaussian[5] optimises a molecule by maximising the symmetry and disregarding all chemical intuition. This means that some bond lengths may have not been optimised for chemical reasons, but to improve the symmetry of the molecule.

Optmising the 'boat' Structure

The boat transition state was then optimised using QST2 at the 3-21G level of theory using the Hartree Fock method. The log file can be found here.

#p HF/3-21G freq opt=qst2 geom=connectivity

route card (6)

The keyword opt=qst2 tell Gaussian to optimise the molecule to a transition state using the method QST2. This method is used when the guess structure is not close enough to the transition state, and involves constructing the reactants and products side by side in a GaussView window, ensuring equivalent atoms have the same labelling, and then running the transition state optimisation. This method initially failed (log filebecause the starting geometry was in the wrong conformation to reach the ‘boat’ transition state. The structure was altered by rotation around the central C-C bond to resemble a more ‘boat-like’ structure. When optimised again to the transition state, this structure gave one imaginary frequency which corresponded to the Cope rearrangement via the ‘boat’ transition structure. [See figure 3 in Appendix 1].

Finding the Reaction Coordinate of Both Confomers

It is impossible to tell which conformers of the product will be obtained from the optimised transition structures because the location of each of the minima for the product conformers of the potential energy surface with respect to the transition states are unknown. To try and visualise the reaction pathway, an IRC (intrinsic reaction coordinate) calculation was run. This gives the minimum geometry closest to the transition state.

Running an IRC for the chair structure ( log file) finished in 87 steps and reached a minimum geometry with structure and energy comparable to that of the ‘gauche 4’ conformer in Appendix 1 of the wiki script[12] [see figure 4 in Appendix 1]. The calculation was run in both directions and was observed to be symmetrical, the curve being similar to that of the Gaussian 'bell' function. The activation energy for the reaction was 0.077 Hartrees or 202.2 kJ/mol[14] (the height of the IRC curve). The curve starts out shallow as the central C-C bond lengthens. When the bond breaks, there is an sharp increase in the gradient leading to the transition state (the peak). The opposite then happens past the transition state or the rest of the curve, hence why the curve is symmetric; the product and the reactant have the same structure and so have the same energy (-231.6 Hartrees).

Running an IRC for the boat structure finished in 45 steps, calculated only in the forward direction, but did not reach a minimum described by one of the conformers in Appendix 1 of the wiki script[12]. It instead reached a local minimum with one imaginary frequency. The structure of gauche 3 can be obtained by ‘cleaning’ the local minimum structure and re-optimising.

Nf710 (talk) 13:55, 5 November 2015 (UTC) A local minimum would not have an imaginary frequency

Thermochemistry

By optimising both transition states and the reactant molecule to both 3-21G and 6-31G* levels of theory, the energy values from the ‘Thermochemistry’ section of the log files and the overall activation energies can be found. Using the structure of the tables from Appendix 1 in the wiki script[12], the following tables contain the results from the Thermochemistry section of the log files of the optimised transition states and reactant.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Energy | Sum of Electronic and Zero-Point Energies | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | Electronic Energy | Sum of Electronic and Zero-Point Energies | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | |

| (0 K) | 298 (K) | (0 K) | 298 (K) | |||

| Chair TS | -231.619322 | -231.461379 | -231.455679 | -234.554065 | -234.413402 | -234.407105 |

| Boat TS | -231.602802 | -231.450926 | -231.445297 | -234.543078 | -234.402324 | -234.395982 |

| Reactant (anti 2) | -231.692535 | -231.539539 | -231.532566 | -234.611710 | -234.469204 | -234.461857 |

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | Experiment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 K | 298.15 K | Imaginary Frequency/ cm-1 | 0 K | 298.15 K | Imaginary Frequency/ cm-1 | 0 K | |

| ΔE(Chair TS) | 205.2

49.05 |

201.9

48.25 |

-775.48 | 146.5

35.02 |

143.8

34.36 |

-532.41 | 140.2 ± 2.1

33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE(Boat TS) | 232.7

55.60 |

229.1

54.80 |

-839.71 | 175.6

41.97 |

173.0

41.34 |

-534.25 | 187.0 ± 8.4

44.7 ± 2.0 |

At both levels of theory, the activation energy for the chair transition state is much smaller so this would be the expected reaction pathway.

There is a significant lowering of both the activation energies and the imaginary frequencies for both the chair and boat transition states at the higher level of theory. This could suggest that the structure is no longer at the transition state initially found by the first optimisation. As frequency is directly proportional to the force constant of the bond (and these frequencies correspond to the bonds formed in the reaction), this means that the optimisation has weakened these 'bonds' At room temperature (298.15 K), the activation energy for both transition states at both levels of theory is smaller than at 0 K. This is because at room temperature, the molecule will have a higher amount of kinetic energy and will therefore be 'closer' to the transition state on the potential energy surface. A general trend taken from this data is that as temperature increases, the activation energy decreases, which could be confirmed by a calculation at a higher temperature.

The activation energy of the chair transition structure calculated in the previous section; 202.2 kJ/mol, is slightly different to those calculated from the values in the Thermochemistry section of the log file. This could be due to the IRC being calculated at a different temperature to 0 K or room temperature; at the 3-21G level of theory, the IRC would have been run at a temperature slightly lower than 298.15 K.

Nf710 (talk) 14:18, 5 November 2015 (UTC) you haven't compared the geometries of the optimised TS for the different levels of theory, therefor you haven't concluded that smaller basis sets do very well at getting the correct geom, but higher basis sets are needed for the energy. In all you have shown a very good understanding of the theory going far beyond, but it would have been nicer if you could have had some more of the vibrations etc within the text to break it up. You just missed a few small things which have brought your mark down, if this was a purely a lit review you would have done very well.

Appendix 1

Figure 2. Chair TS Imaginary Vibration |

Figure 2. Chair TS Imaginary Vibration |

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

This section will look at two different Diels Alder cycloaddition reactions. Reaction 1 is the reaction between cis butadiene and ethene, and reaction 2 is between cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride.

Reaction 1: Cis butadiene and Ethene

Calculations

Using the semi empirical AM1 method, both the cis butadiene and ethene fragments were optimised and their orbitals generated. The log file for butadiene can be found here, and for ethene can be found here

#p AM1 opt geom=connectivity

route card (7)

Cis butadiene is not the lowest energy configuration of butadiene, this being the trans conformer, but only the cis conformer will react via Diels Alder.

The transition state of this Diels Alder reaction was created by putting the ethene and cis butadiene optimised fragments together and ‘cleaning’ the structure. A transition state optimisation was then run similar to that of optimisation 1 in the tutorial, the log file for which can be found here.

#p AM1 opt=(calcfc,ts,noeigen) freq geom=connectivity

route card (8)

An IRC was then run in both directions ( log file).

#p AM1 irc=(maxpoints=200,calcall) geom=connectivity

route card (9)

Discussion

The reaction between cis butadiene and ethene is a [π4s +π2s] Diels Alder cycloaddition, as both of the orbital fragments react from the same plane at each end, hence the 's' suffix. The HOMO of the cis butadiene and the LUMO of the ethene are antisymmetric with respect to the imaginary plane perpendicular to the plane of each of the fragments. The LUMO of the cis butadiene and the HOMO of the ethene are symmetric with respect to this plane. Therefore, these are the pairs of orbitals that interact in this Diels Alder cycloaddition. [See figures 1 and 2 from Appendix 2]. The HOMO of the transition state [figure 4, Appendix 2] is antisymmetric with respect to this plane, and the LUMO [figure 5, Appendix 2] is symmetric with respect to the plane. These symmetries allow a prediction to be made as to which orbitals will react and form new bonds in the Diels Alder reaction; the HOMO of the transition state is formed from the HOMO of the cis butadiene and the LUMO of the ethene, and therefore the LUMO is formed from the LUMO of the cis butadiene and the HOMO of the ethene.

The bond lengths of the newly formed bonds in the transition state were measured at approximately 2.12 angstroms. These bond lengths are smaller than the van der Waals’ radii (1.96 Å[15]; there are two radii in between the carbon atoms) but larger than both the sp3 (1.53 Å[16]) and the sp2 (1.34 angstroms[16]) C-C/C=C bond lengths. This confirms the structure contains partially formed bonds/a strong interaction as expected in a transition structure. As the bond lengths for the bonds in the transition state are roughly equal, it suggests that the reaction is concerted and the bonds form simultaneously. This structure was confirmed as a transition structure by the calculation of one imaginary frequency corresponding to the bonds being formed in the cycloaddition. [see figure 7 in Appendix 2]. This vibration is symmetric with respect to the bonds being formed which also suggests that the reaction is concerted. The real vibration with the lowest frequency value has a vibration which is asymmetric with respect to these bonds and shows the rotation of the ethene molecule with butadiene remaining stationary [see figure 8 in Appendix 2]. This vibration could potentially correspond to an antibonding interaction.

The IRC of this reaction [Figure 6 in Appendix 2] starts with the reactants from the right hand side of the curve. As the reactants come together, the energy slowly starts to rise until they reach the transition state; the peak in the curve. Forming the bonds results in a large and quick release in energy shown by the much steeper downward gradient in the reaction path. The curve then plateaus as it reaches the energy minimum on the surface described by the product of the reaction. From this curve, the activation energy (ΔG‡) is 97.22 kJ/mol and the reaction energy (ΔG0) is (-)224.8 kJ/mol. The energies shown on the graph are in atomic units (Hartrees) and were converted into kJ/mol using an online converter.[14]

Reaction 2: Cyclohexadiene and Maleic Anhydride

Calculations

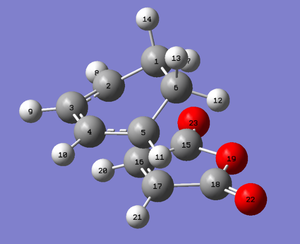

Using the semi empirical AM1 method via route card (7), the structures for both cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride were optimised and the orbitals generated . The cyclohexadiene log file can be found here, and the maleic anhydride log file can be found here. Again, the endo and exo transition state structures were optimised using the technique from optimisation 1 in the tutorial via route card (8) (Exo: here, Endo: here). The technique from optimisation 1 on reaches the transition state when the initial transition state guess structure is close to the optimised structure. The technique from optimisation 2 was also tested to compare the results of the two different methods and it was found that both techniques yielded the same result.

Both transition structures were confirmed to be correct by the presence of an imaginary frequency after a frequency calculation (incorporated within the optimisation calculation using both keywords simultaneously). These vibrations corresponded to the formation of the two new bonds in the Diels Alder reaction.

Discussion

This reaction between cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride is also a [π4s +π2s] Diels Alder cycloaddition. The 4π system is similar to that of the cis butadiene in reaction 1, just with an extra [-CH2CH2-] fragment attached to complete the six membered ring.

Due to an evident Gaussian bug, the IRCs for the endo and exo transition states of this reaction gave some problems. The exo transition state gave an extra point at the zero energy line at the transition state, even though there is already a point on the curve at the transition state. The endo transition state could only compute the forward and backward reactions separately. This could be due to the fact it was optimised via TS(Berny) instead of QST2 so a reactant and product had not been specified.

(Did you try running the IRC after a QST2 calculation? I don't think there would be a real difference between running an IRC with Berny or QST2, but then again we don't know what's causing the bug Tam10 (talk) 14:32, 28 October 2015 (UTC))

The relative energies of the exo and endo transition structures are -132.4 kJ/mol and -135.2 kJ/mol respectively. The exo transition structure, as expected, is higher in energy and so the energy difference between the starting structure and the transition state should be larger. Therefore, this suggests that the endo product is kinetically preferred. The structural difference between the endo and the exo form is the difference in the bridging group of the 6 membered ring adjacent to the furan oxygen; the endo form neighbours the C=C double bond bridge and the exo form neighbours the C-C single bond bridge. There is potential for the exo form to be more strained because of the lack of extra stabilisation from the so called ‘secondary orbital effect’. However, thermodynamically, the exo product is the most stable; the exo product energy is lower than that of the endo product. However, this is not shown by the results table below. This could be due to the Gaussian bug producing an error in the results.

| Reactant energy/ kJ/mol | Transition state energy/ kJ/mol | Product energy/ kJ/mol | Activation energy/ kJ/mol | Reaction energy/ kJ/mol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo | -250.4 | -132.3 | -419.7 | 118.0 | -169.3 |

| Endo | -247.6 | -135.2 | -420.4 | 112.4 | -172.8 |

(The reactants should have the same energy for both cases. I suspect you might have read the energies from the IRC? This might be putting your activation and reaction energies off a little Tam10 (talk) 14:32, 28 October 2015 (UTC))

The HOMO of the exo transition state [see figure 11 in Appendix 2] is antisymmetric with respect to the nodal plane shown down the centre of the picture. The major contribution around the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment is from the antibonding orbital, however, there is no stabilisation from the secondary orbital overlap effect because the π systems are not close enough to each other to interact.

The HOMO of the endo transition state [see figure 12 in Appendix 2] is also antisymmetric with respect to the nodal plane shown down the centre of the picture of the molecular orbital. The orbitals that would interact appear to be out of phase with each other and there is no interaction between the antibonding orbital on the carbonyl groups and the bridging alkene, suggesting there is no secondary orbtial overlap effect, or none that can be observed from these calculations.

| Transition 'bond' lengths/ Å | Distances between carbons in -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- / Å | Distance between carbons on the 'opposite' bridge to -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- / Å | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exo | 2.170 (carbons 2-10 and 5-17 from the below exo diagram) | 2.280 (carbons 15 and 18 from the below exo diagram) | 1.522 (carbons 1 and 6 from the below exo diagram) |

| Endo | 2.162 (carbons 5-17 and 2-16 from the below exo diagram) | 2.279 (carbons 15 and 18 from the below exo diagram) | 1.397 (carbons 3 and 4 from the below endo diagram) |

| Exo | Endo |

|---|---|

|

|

Comparison of DFT and AM1

As discussed the introduction, AM1 is a simplified form of DFT, as it simplifies the Hartree-Fock equation in order to solve the Schrödinger's Equation in a computationally cheaper way. This section compares the effects on the activation energies and orbitals produced by using the two different computation methods.

The transition states for the cis butadiene and ethene Diels Alder cycloaddition reactions were reoptimised using DFT; B3LYP at the 6-31G* level of theory (route card (1)). Below is the difference that this optimisation makes to the HOMO and the LUMO compared to the AM1 optimisation.

| HOMO | LUMO | |

|---|---|---|

| AM1 |

|

|

| DFT |

|

|

To compare the difference DFT makes to the activation energy and overall reaction energy, the IRC of the same Diels Alder was run from this optimised transition state. The IRC can be viewed in Appendix 2 [figure 13].

| ΔE(TS)/ kJ/mol | Reaction Energy/ kJ/mol | Imaginary Frequency/ cm-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AM1 | 97.22 | -224.8 | -956.22 |

| DFT | 81.39 | -249.4 | -525.00 |

The nodal properties of the HOMO have completely changed in the HOMO but the LUMO has remained similar to that in the calculation from AM1. This is because the DFT calculation has a much higher basis set and so includes more orbitals in its calculation, resulting in a more accurate HOMO and LUMO. It can be predicted that this will cause a change in the activation and reaction energies.

The imaginary frequency has lowered, meaning that the strength of the bonds created at the transition state is weakened. DFT has decreased the size of the activation energy, but increased the magnitude of the reaction energy. It would be invalid to compare the absolute energies of the compounds calculated in DFT and AM1 because they are on different scales; only the energy difference such as activation energies make sense.

Appendix 2

Figure 7. Imaginary cyclohexene frequency |

Figure 8. Real cyclohexene frequency |

Conclusion

The Cope rearrangement chair and boat transition states were optimised using DFT at 3-21G and 6-31G* levels of theory and the reaction pathways were examined by running IRCs. It was deduced that the chair transition state was more favourable because it had a smaller activation energy. It was also deduced that at as the temperature increases, the size of the activation energy decreases as the reactants move 'closer' to the transition state on the potential energy surface.

The Diels Alder cycloaddition transition states for two different reactions were optimised and their IRCs run. The cis butadiene and ethene reaction was analysed by Frontier Orbital Theory and a conclusion obtained that the reaction was thermally allowed following the Woodward-Hoffmann rules. The cyclohexdiene and maleic anhydride reaction compared the endo and exo products to see which product would be the most observed in the reaction. A Gaussian bug proved these calculations to be difficult and so not direct conclusions could be made, but it could be observed that the endo product is preferred kinetically because it had a lower activation energy (it would be the most observed in a reaction). Secondary orbital overall was also not observed, as the orbital pictures calculated gave no evidence that the interaction arose.

In these calculations, it is assumed that there is one solitary molecule undergoing the Diels Alder reactions, neglecting the effect of surrounding molecules when reacting in solution. It also assumes that a highly accurate level of theory is being used to compute the orbitals which AM1 is not. Therefore, the calculations could be improved by using a much higher level of theory. Comparing DFT and AM1, DFT, at a higher level of theory than AM1, produces more accurate molecular orbitals with different nodal properties to those produced by AM1.

A further calculation could be to extend the Cope rearrangement experiment by examining antisymmetric 1,5-hexadiene to see how the orbitals and the regioselectivity are affected.

References

- ↑ Woodward RB, Hoffmann R. The Conservation of Orbital Symmetry. Germany: Verlag Chemie GmbH Academic Press Inc.;1971.

- ↑ http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/local/organic/pericyclic/p1_sigma.html

- ↑ http://www.organicchemistry.com/mechanism-of-the-diels-alder-reaction/

- ↑ Rowley CN, Woo TK. A Computational Experiment of the Endo versus Exo Preference in a Diels Alder Reaction, J. Chem. Edu. 2009, 86 (2), p 199

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Gaussian 09, Revision D.01, Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Caricato, M.; Li, X.; Hratchian, H. P.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Bloino, J.; Zheng, G.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Montgomery, J. A., Jr.; Peralta, J. E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Knox, J. E.; Cross, J. B.; Bakken, V.; Adamo, C.; Jaramillo, J.; Gomperts, R.; Stratmann, R. E.; Yazyev, O.; Austin, A. J.; Cammi, R.; Pomelli, C.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Voth, G. A.; Salvador, P.; Dannenberg, J. J.; Dapprich, S.; Daniels, A. D.; Farkas, Ö.; Foresman, J. B.; Ortiz, J. V.; Cioslowski, J.; Fox, D. J. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009.

- ↑ Fox MA, Cardona R, Kiwiet NJ, Steric effects vs. secondary orbital overlap in Diels-Alder reactions. MNDO and AM1 studies, 1987, 52 (8), pp 1469–1474

- ↑ Sholl D, Steckel JA. Density Functional Theory: A Practical Introduction. New Jersey: A John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Publication

- ↑ Echenique P, Alonso JL. A mathematical and computational review of Hartree-Fock SCF methods in Quantum Chemistry. Molecular Physics, Vol. 00, No. 00, DD Month 200x, 1–64

- ↑ Kim K, Jordan KD. Comparison of Density Functional and MP2 Calculations on the Water Monomer and Dimer. J. Phys. Chem. 98(40): 10089-10094

- ↑ Ditchfield, R; Hehre, W.J; Pople, J. A. (1971). "Self‐Consistent Molecular‐Orbital Methods. IX. An Extended Gaussian‐Type Basis for Molecular‐Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules". J. Chem. Phys. 54 (2): 724–728.

- ↑ Dewar MJS, Zoebisch EG, Healy EF, Stweart JJP. Development and use of quantum mechanical molecular models. 76. AM1: a new general purpose quantum mechanical molecular model, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,1985, 107 (13), pp 3902–3909

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:phys3

- ↑ Seray RA, Jewett JW. Physics for Scientists and Engineers. USA:Brooks/Cole;2003

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 http://www.colby.edu/chemistry/PChem/Hartree.html

- ↑ Allinger NL. Molecular Structure: Understanding Steric and Electronic Effects from Molecular Mechanics. New Jersey:John Wiley & Sons, Ltd;2012

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Brown WH, Iverson BL, Anslyn EV, Foote CS. Organic Chemistry: 7th Edition. USA:Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning;2012