Rep:Mod:god22122

Daniel Godfrey - 03/02/2009 - Inorganic Computational Laboratory

Bonding (Ab-Intio and DF-MO Theory)

Introduction

Computational modelling is used in inorganic chemistry in direct contrast to its use in organic chemistry. Difficulties in reproducing the level of complexity involved in unconventional bonding types is a common limitation in treatment of inorganic molecules which is a published limitation of molecular mechanics approaches in particular. For these reasons, inorganic chemists will aim to gain information on a molecule on the basis of the energetics of its approximate transition states and also the form of excited activated complexes. Importantly reaction profiles can be studied via the retrieval of values such as energy of activation (ETS#) from the calculated energy of stable reagent states.

Critically spectroscopic characteristic of molecules can be investigated and predicted for use in species assignments. Introducing increased levels of electronic complexity into the calculation interface can prove very useful in assignment of bonding types and the electronic distribution surrounding a molecule, thus calculating localised reactive regions of species.

Much of the work done will involve the computational consideration of the potential energy surface of the molecule in question. Optimisation of the molecule will involve the method trying to find the lowest energy point of the potential energy well that is approximated by the simple harmonic motion approximation. The computational method traverses the potential energy surface by changing the nuclear coordinates and calculating the energetics of the system in terms of electrostatic and steric arguments. This will be the stimulus to find the lowest energy structure attainable to the accuracy decided by the level of quantum mechanical treatment included in the method and the ability of the mathematical functions that describe the basis set to accurately predict the electronics of the molecule. The basis set may be improved in terms of quantity of functions incorporated. By this it is clear that the iterative type calculation process may benefit from an increase in the number of periodic Fourier functions used to attempt to describe the molecular wavefunction to a greater degree. The basis set may also be improved in terms of quality of functions incorporated. In this case it is also true that changing the basis set to incorporate the functions that describe the orbitals that best approximate the molecular system. The trade off that often needs consideration is optimum balance between decreasing computation time that is increased by increasing accuracy by the two means suggested above and obtaining a degree of accuracy that allows reliable analysis and interpretation of the output of the calculation.

The optimised structure is that found in the gas phase when energetic availability is not a structure determining factor and therefore intermolecular considerations are overcome. In solid and liquid phase optimum structures are an important issue and the structure observed will be manipulated from the gas phase structure in order to minimise these effects.

On many conventional bonding situations it is a useful approximation to only consider the electrons which dominate the bonding interactions. For this reason all electrons that are non-bonding can be grouped into an overall effect that is modelled by a function called a pseudo-potential. This simplifies calculations by not significantly changing the results, however at the forefront of physical chemistry the effort must be made to obtain the best calculation for under-researched issues to attempt to provide evidence for or against theoretical conjecture.

Part 1: Molecular Energy Considerations

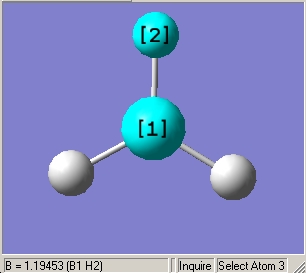

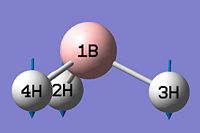

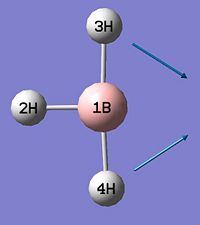

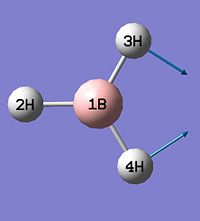

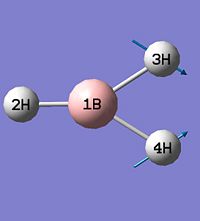

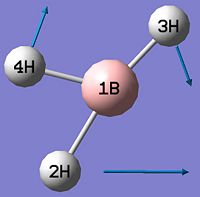

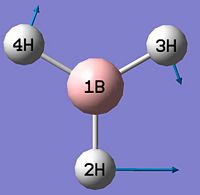

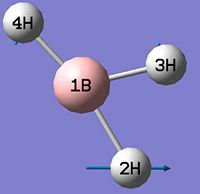

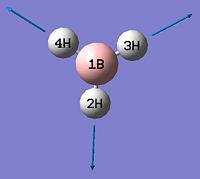

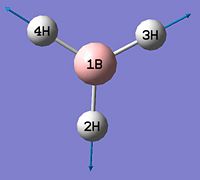

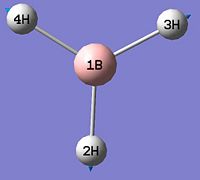

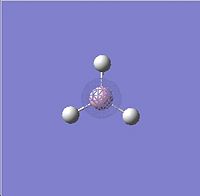

BH3

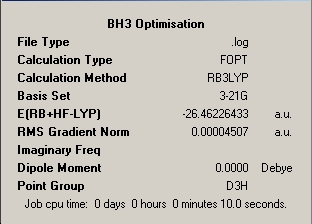

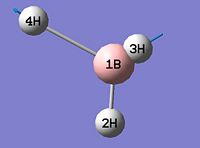

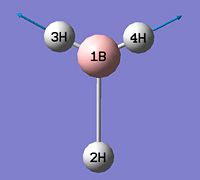

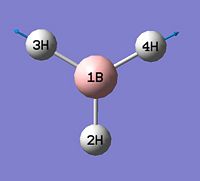

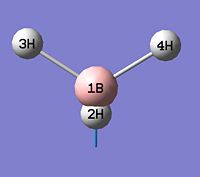

BH3 was optimised by the B3LYP DFT method using the 3-21G basis set giving a low level of accuracy by considering a simple array of orbital functions yielding a rapid calculation. The methods iteratively solves the Schroedinger equation for the orbital functions dictated by the basis set used finding the lowest energy arrangement of the molecules. Increasing the complexity of the basis set used will of course account for more electronic effects that dictate the optimised structure of the molecule, however there is a trade-off between degree of accuracy and calculation time and for simple molecules the extra calculation time is not warranted as it will not greatly affect the overall optimised structure significantly. Allowing scaling of wavefunctions and increasing number of describing functions increases accuracy of approximation by using the 'Weinbaum' and 'Variational' parameters.

The Weinbaum and variational parameters allow for manipulation of the degree of intrinsic covalency of bonding interactions in a molecule whilst the variational parameter changes the shape of the orbital whilst keeping the overall volume constant to the Schroedinger solutions dictated by consideration of the LCAO coefficients. These parameters allow for the electronic effects such as variable diffuse nature of orbitals and intrinsic polarisation of molecules. Both types of scaling are important for the consideration of inorganic molecules where electron density distribution is complex. The following optimised geometry is obtained:

- B-H bond length (all equivalent to accuracy shown) = 1.19Å

- H-B-H angle (all equivalent) = 120.0o

∆Table 1 - Consideration of the Optimised BH3.

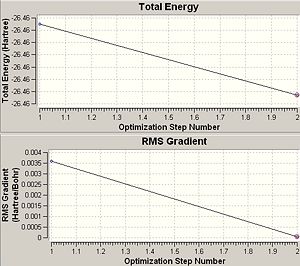

The calculation summary confirms that the optimised structure has D3h symmetry and the calculation time is low as a low number of iterative cycles is needed to obtain a gradient of below 0.001 which dictates the optimisation of a molecule.

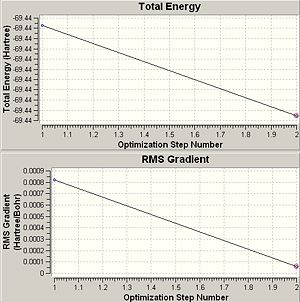

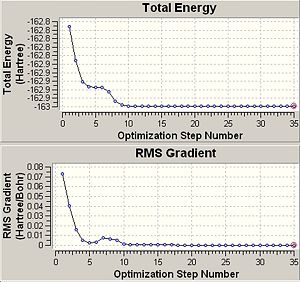

The graph entitled 'Total Energy' shows the change in energy of the molecule through the course of the optimisation (time) whilst the graph entitled 'RMS Gradient' signifies the first derivative (or 'rate of change') of the energy of the molecule during the computational method. The latter identifies the value of the RMS gradient at each optimisation stage and in this case the gradient signifies the inverse rate of convergence of the energy, where a highly negative RMS gradient shows that the current iterative energy of the molecules is a large distance away from the minimised energy and a low RMS gradient (~0) shows an optimisation energy that is close to the minimised energy of the adjacent stationary point signifying the minimum of the molecule's potential energy surface and the optimum internuclear separations have been obtained. RMS stands for root mean squared which is a statistical method of averaging the system being considered and the minimised energy is the ground state energy of the molecule as dictated by Hammond's Postulate.

Of course by the above reasoning and practical application of the variational theory the last structure obtained as the 'optimised structure' will be the most negative in energy and have the smallest gradient. This is due to the stipulation that the lowest energy conformation will be the ground state of the molecule in question and the fact that gradient is the smallest possible value signifies that a minimum energy has indeed been obtained. The calculation can result in a structure that has not reached a minimum value and therefore gradient close to zero and for this reason each optimisation must be checked to ensure that the gradient immediately adjacent to the end point of the optimisation is below a certain critical value reported to be 0.001[1]. This can be observed from the summarised results of the optimisation seen in table 1, where the final gradient is two orders of magnitude smaller than the critical value. Therefore, the most negative energy and the smallest gradient is observed for the optimised geometry showing that the method has arrived at a structure that it believes to be the lowest energy possible for that degree of computational complexity and hence the most accurate description of the ground state of the molecule that the method can achieve and no net electrostatic forces act upon the molecule as a whole and the system is in equilibrium. Until equilibrium is reached unfavourable electrostatic interactions between like-charges exerts a force onto the molecules to change position into a more favourable array with a lower energy. This of course assumes that the method has proceeded correctly and fully optimised the structure, which must be checked as mentioned earlier.

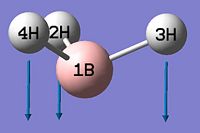

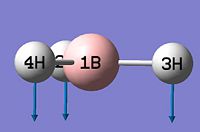

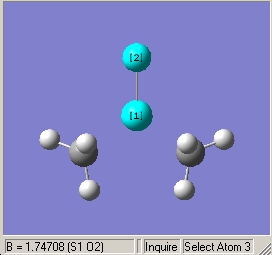

As can be seen from figure 1 the optimised geometry only shows a series of atoms that aren't connected by conventional 'bonds' but are instead suspended in an invisible confined array. This is cited as being due to the optimised distance exceeding what GaussView expects the bond length to be. One chosen definition of a bond that is relevant in the case of computational approach, is the generation of a species with a newly formed interaction between two independent particles that exhibits a preference to forming over remaining independent, which results in satisfying the characteristic nature of the two molecules.

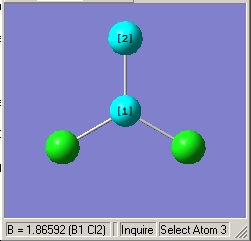

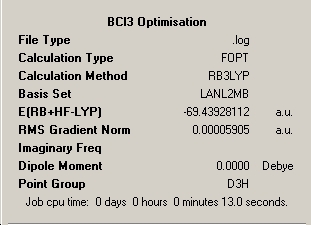

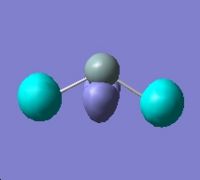

BCl3

The same process was carried out for the molecule BCl3, using the same method and basis set as BH3, and also using the same method using a slightly more complex basis set called LanL2MB [which begins to incorporate pseudo potentials]. The aim of this process is to determine the effect on simple parameters such a bond lengths and angle for a simple trivalent molecule. Both basis sets are still relatively simple and calculation times were similarly low. Once again the optimised geometry is the stable atomic arrangement with nuclear positions that approximate to the bottom of the potential energy surface for the molecule. The substitution of hydrogen in the previous example for chlorine leads to comparison of the differing electronic nature of each molecule, with chlorine being larger in size and possessing more electrons. Pseudo-potentials are often required for accurate consideration of heavier elemental substituents such as chlorine and should yield a better approximation, however it will be interesting to see the difference between the two approachs for such a simple molecule. The optimised bond lengths and angles by the two methods is shown below:

- B-Cl Bond length (All equivalent to accuracy quoted) = 1.78Å for 3-1G2 Basis Set

- B-Cl Bond length (All equivalent to accuracy quoted) = 1.87Å for LanL2MB Basis Set

- Cl-B-Cl Angle (Equivalent for both basis sets) = 120.0o

Despite the low complexity of the molecule the necessity of using a low-level pseudo-potential basis set is observed, as assuming the LanL2MB approach is more accurate in this case, the 3-1G2 basis set produces a value which has a relative error of 4.8% which is relatively large for a small molecule. The table below shows the results produced for the more accurate LanL2MB basis set.

∆Table 2 - Consideration of the Optimised BCl3.

The total energy of the molecule during the optimisation does not change in two decimal places of the unit Hartree, however this can be misleading as Hartree is a large unit. In knowing the optimised energy (summary), in standard units of Joules per mole of molecules of BCl3 the energy could not have changed more than 13.2kJmol-1 from the input structure to the optimised structure with a relative error of 1kJmol-1 (3.8x10-4Hartree. This is a relatively large value and no real analysis of this graph can be made except to comment that due to the low calculation time of 13 seconds and linear plot of 'Total Energy' means that the number of iterative steps was low and from this it must be assumed that the change in energy was much lower than the maximum value. The log file of the optimised structure would shed more light into the change of energy.

The optimisation pane for the optimised structure shows that the file and calculation type are .log and FOPT (Fourier Optimisation) respectively, reflecting the iterative nature of the calculation. A final energy was obtained of -69.439Hartree, and as expected a dipole moment of 0.0 D was obtained due to three approximately equal polarisation vectors acting at 120.0o to eachother and cancelling eachother out in the two dimensions considered in the D3h. The calculation time was slightly longer than that of BH3 at 13 seconds which corresponds to an increase of 30% from substituting hydrogen for the more complex Chlorine. The optimisation was clearly successful, as noted, because the optimal RMS gradient was less than 0.001.

|

Optimised Atomic Coordinates |

Charges According to Heavy Atom Pseudo Potential |

Further Calculation Properties |

|

B1 (0.0, 0.0, 0.0) |

B1 = 0.564142 |

-Seven cycles using standard basis: LANL2MB (5D, 7F): with 8 symmetry adapted basis functions of A1 symmetry, 1 symmetry adapted basis functions of A2 symmetry, 5 symmetry adapted basis functions of B1 symmetry and 3 symmetry adapted basis functions of B2 symmetry |

∆Table 4 - Log file consideration for optimised DMSO.

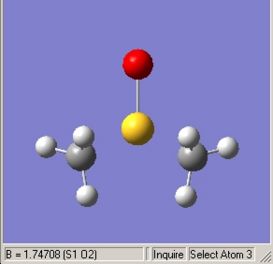

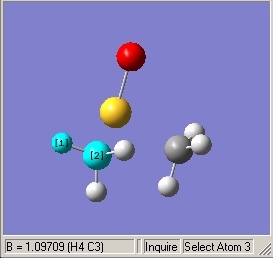

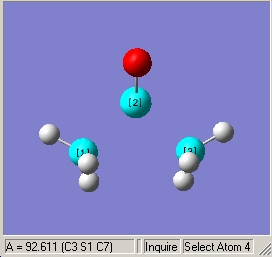

Independant Work - DMSO

Placing the file on D-space yielded an error so the file was uploaded as a .txt file and published here [1]

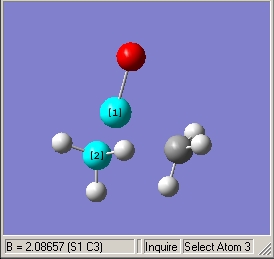

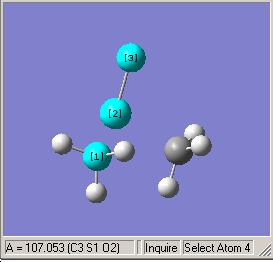

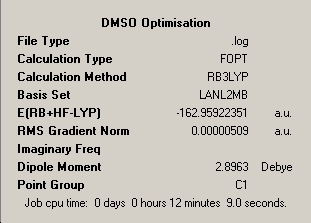

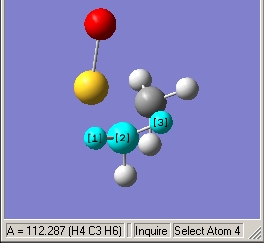

The molecule I have chosen to consider is dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) which is frequently used as a polar aprotic solvent or nucleophilic reagent in synthesis. Its point group is Cs which was constrained prior to calculation to reduce calculation times. Below in table 3 the optimised structure is shown with the molecules optimised geometry annotated. The calculation method and basis set used were B3LYP and LanM2MB respectively using FOPT as the iterative calculation type.

From the molecules log file various properties that were of particular note were given as follows:

|

Optimised Molecular Form and Data |

Optimised Bond Lengths |

Optimisated Bond Angles |

|

|

|

|

- Pre-described non-bonding due to exceeding critical value for bond length |

- Illustrated C-H bond length of 1.10Å |

- Illustrated C-S-C bond angle of 92.6o |

|

|

|

|

- Optimisation plots showing local minima and maxima |

- Illustrated C-S bond length of 2.09Å |

- Illustrated C-S=O bond angle of 107.1o |

|

|

|

|

- 'RMS Gradient Norm' is less than 0.001 (Optimised!) |

- Illustrated S=O bond length of 1.75Å |

- Illustrated H-C-H bond angle of 112.3o |

∆Table 3 - Consideration of the Optimised DMSO.

|

Optimised Atomic Coordinates |

Charges According to Heavy Atom Pseudo Potential |

Further Calculation Properties |

|

S2 (-0.001069, 1.727875, 0.462315) |

S2 = 0.023197 |

- Dipole moment (field-independent basis, Debye): |

∆Table 4 - Log file consideration for optimised DMSO.

The finalised energy is given as -162.959Hartree, however interestingly the optimisation plot shows a non-linear plot and has a much longer calculation time than the previous two molecules of 12 minutes 9 seconds. This fact can put down to the differing angles of exertion of electrostatic forces in order to find the optimum geometry and the much higher complexity of the molecule. This fact is decided in essence by the point group symmetry of the molecule, as the higher symmetry of the BCl3 and BH3 molecules and their C3 axes of rotation dictates that the iterative cycles move all three equivalent outer atoms in tandem to find the optimum equivalent bond lengths. This process means that the dipole moment of the molecule remains constant throughout the process and a linear plot of total energy against time is obtained assuming each iterative cycle takes approximately the same amount of time. DMSO has much lower Cs symmetry and this dictates that electrostatics exert forces which have differing angular components which has the effect of moving the atoms in differing directions, manipulating the dipole of the molecule which has the effect of producing a non-linear graph of 'Total Energy'. It is visible from both optimisation plots that a local minimum is reached at approximate energy -162.95 Hartree and iteration step 5 respectively. The formation of a local minimum potential is shown by the RMS gradient and in fact the gradient reaches a positive value between iteration steps 6 and 7. It is highly impressive that the method continued and traversed the local minimum and maximum to reach a lower overall optimised potential. The reasons why this occured is because the gradient was not constant enough i.e. below 0.001 to small changes of nuclear coordinates so the iterations continued and identified the minimum as local. Had the iteration stopped at the local minimum an energy discrepancy of 0.05Hartree or 131.3kJmol-1 would be seen in the optimised energy of the molecule which would have had a huge effect on the optimised geometry obtained.

As expected the optimal dipole moment is much higher at 2.90 D which is a parameter which is inadvertantly minimised suring the optimisation process as it is unfavourable and destabilising for a non-ionic molecule to possess a high dipole moment as it represents charge separation in covalent molecules as originally studied by Debye.

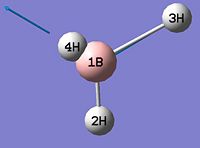

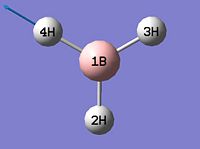

Vibrational Analysis

As access was denied to D-space the BH3 file was uploaded as a .txt file here: [2]

A vibrational frequency analysis was carried out for BH3 by changing the calculation type to frequency and optimisation on the Gaussian input file which adds to the script as per below. The pop=(nbo,full) keyword is added to carry out full molecular orbital analysis sequentially in the Gaussian calculation.

# freq b3lyp/3-21g pop=(nbo,full) geom=connectivity

BH3 Frequency

0 1

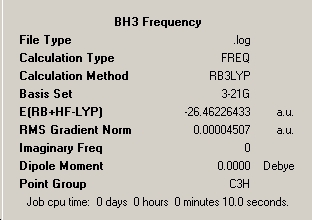

As explained in the literature the second derivative of the potential energy surface is the frequency analysis, and it is known that the means of classifying the nature of a stationary point is via the sign of the second derivative, in this case, of the total energy. It the second derivative has a positive value then the location being considered is a minimum point or stable geometry, if the second derivative is negative a maximum point is obtained which falls in line with the concept of an unstable transition state. If the second derivative is a mixture of the two then the point being considered is unimportant in terms of energy and the calculation has failed to locate a stable conformation and reasonable approximation of the ground state equilibrium geometry. In that respect the second derivative or frequency analysis is useful in providing the answer to the question 'has the molecule been optimised?'. The frequency analysis also calculates the Infrared transitions for the molecule and ultimately a predicted IR spectrum which can be easily compared to experimentally obtained results. The summary for the frequency analysis of BH3 has been included below.

|

Frequency Analysis Summary |

|

|

- Calculation time of 10 seconds |

∆Table 4 - Consideration of the Frequency Analysis of BH3.

The energy quoted by this optimisation shows no change in 8 decimal places of Hartree which means that the molecular geometry found was indeed the correctly minimised structure, which is intuitive due to the effective 2D optimisation which limits error. It is important that this is the case as if a different energy had been obtained than the original structure would not have been a critical point in the potential energy surface of the molecule, which can easily be envisaged as being the case for large molecules. The imaginary ('negative') frequencies column counts the number of inverse frequency vibrational modes calculated, and remembering the relationship between the second derivative and the frequency analysis, the fact that it is zero shows that a minimum point has been obtained. Had one negative frequency been counted by the method the located position on the potential energy surface would be a transition state. Had the number been greater than one the calculation would have arrived at an unimportant location on the potential energy surface.

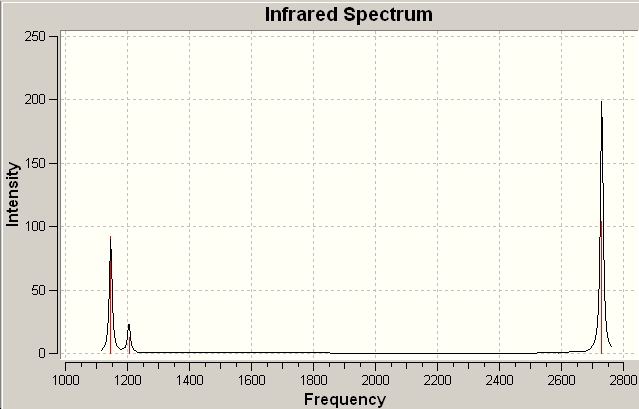

As previously mentioned the calculation type has been changed in order to produce the predicted IR spectrum for the molecule. The same basis set was used as no 'heavy atoms' are included in the molecule and the 3-1G2 basis set is sufficient to describe the simple molecule. The point group has changed from D3h to C3h, which may be due to the consideration of non-planar vibrations. The six vibrations of the BH3 molecule are considered below.

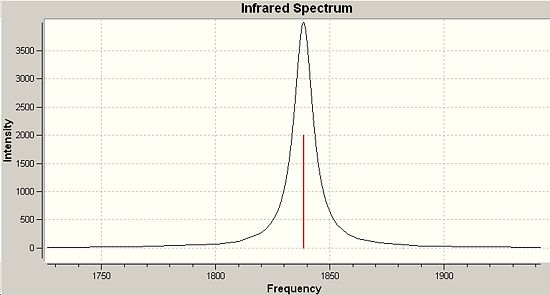

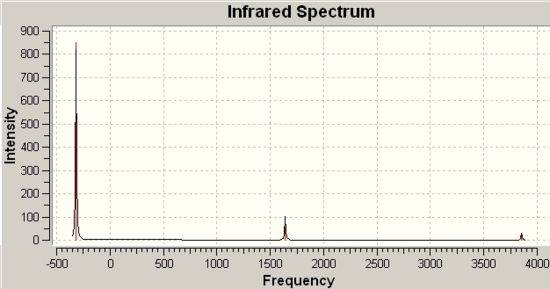

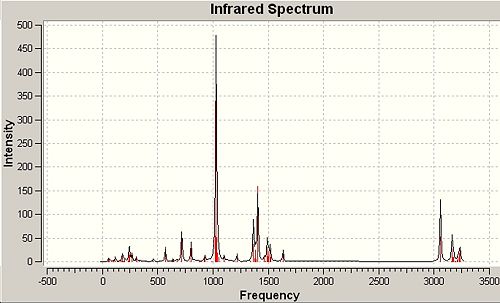

∆Figure 1 - Infrared Spectrum produced by frequency analysis of BH3.

There are clearly less than six vibrations observed in the IR spectrum for BH3. This is because each vibration has an associated intensity (perhaps an intrinsically low resonance intensity) which can depend on the energy required to activate the vibration, hence the energy available and also the interference of vibrations of similar energy. In this case one vibration may override the other and be the only one that exhibits itself.

∆Table 5 - Vibrational Analysis of BH3

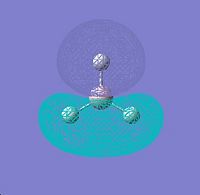

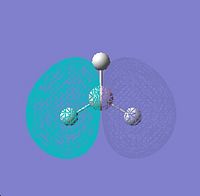

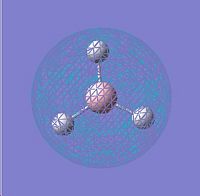

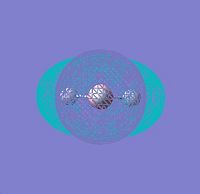

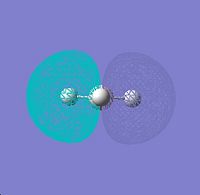

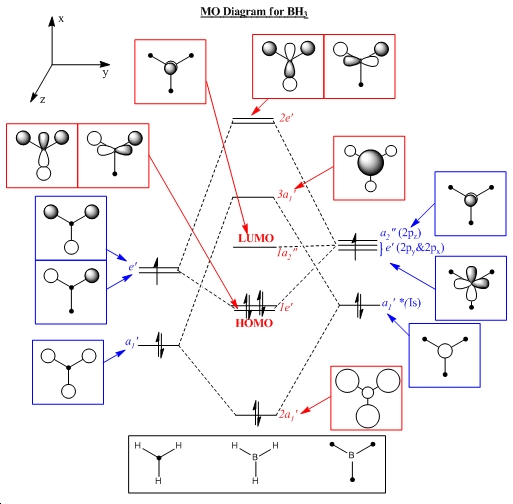

MO Analysis

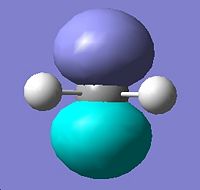

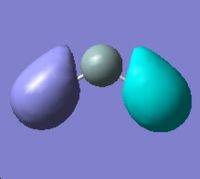

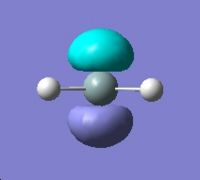

The unoccupied orbitals are intrinsically more diffuse than the occupied orbitals. They are therefore more complex to interpret and so they are not considered. Below is featured the molecular orbital diagram has been humanly processed from well tested rules and principles derived from first principles. The two representations are shown to show good visual concordance to each other with the three computationally derived HOMO (two degenerate) and LUMO orbitals being the linear combinations of the atomic orbitals combined in the diagrammatically derived surface. This process is intuitive with respect to considering the constructive and deconstructive regions caused by linear combination of the atomic orbitals into one overall surface or molecular orbital.

|

HOMO - 2 |

HOMO - 1 |

Degenerate HOMO px |

Degenerate HOMO py |

LUMO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

∆Table 6 - Visual Representations of the Molecular Orbitals of BH3

∆Figure 2 - Conceptual Representations of the Molecular Orbitals of BH3 based on the constituent atomic orbitals.

One major difference between the two representations is that the computational molecular orbitals suggest that the non-bonding orbital is the px orbital when the hand-derived diagram suggests it should be the pz orbital that remains non-bonding. The reasoning for this dicrepancy is unclear unless it is due to the minimal basis set not being great enough to accomodate for the difference in treatment.

This is the only one significant differences between the two representations apart from the exact combination of orbitals, as only the relative contributions from each atomic orbital is considered in the diagrammatical approach. The accuracy of the qualitative computational approach is therefore very high and agrees highly with derived results. Computational approach is used to produce the MOs relatively rapidly for small molecules although it can be done competently by fragmenting a molecule and considering the symmetry and relevant atomic or fragment orbitals that combine to form the molecule. Therefore the massive advantage of the computational approach is to calculate quickly the molecular orbitals of molecules that must be fragmented many times to gain enough simplicity to eventually obtain the complex molecular orbitals. Combination of the mixed orbitals will be difficult to combine in corrrect proportion and are much better dealt with computationally.

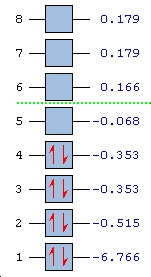

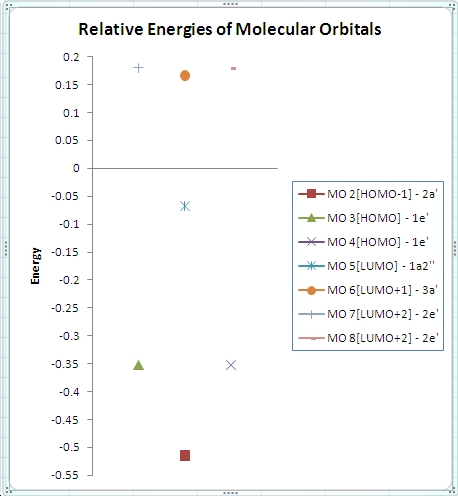

∆Figure 3 - Computed energies for the molecular orbitals of BH3 and the corresponding plot of the energy levels.

From the above plot of the computed relative energies of the molecular orbitals featured in the hand-derived diagram it can be seen that a similar pattern can be seen. However it is also clear that only an empirically expected splitting of interacting orbitals can be conceptually arrived at and it is highly mathematically involved to achieve the exact energies of each molecular orbital of BH3. The limitations of the non-computational diagram is therefore that it can be difficult to arrive at the correct energy spacings between the molecular orbitals due to varying degrees of interaction of 'fragment orbitals'. In turn the advantage of the computational approach is that much more accurate approximations to the relative energies of the molecular orbitals are calculated which can easily be compared in a plot such as the one above. Of course the accuracy of the energies calculated is highly dependent on the method and basis set utilised.

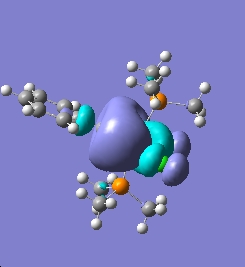

Part 2 - Isomers of Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2

The optimised structures log files could not be input to D-space and so cis and trans respectively have been placed as .txt files here: [3] [4]

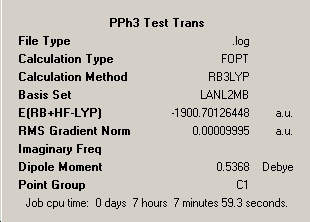

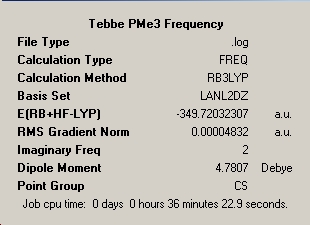

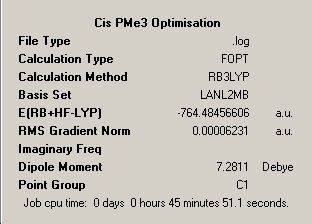

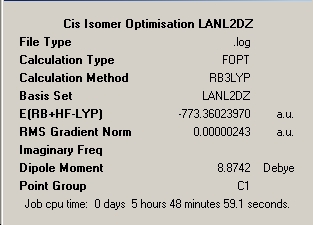

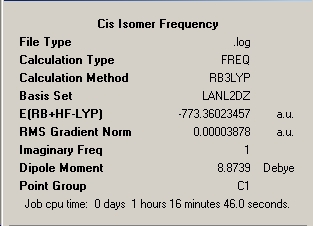

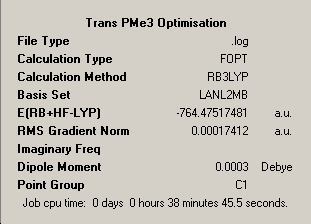

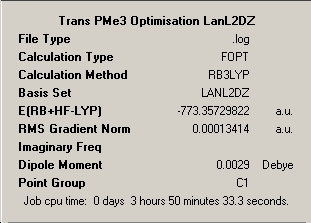

The aim of this section is to use calculations to predict the thermal stability and spectral characteristics of the cis and trans isomers of the titled Molybdenum tetracarbonyl complex. The two structures were optimised using a low level pseudo-potential LANL2MB and the method B3LYP followed by the final optimisation of both of these geometries using the more accurate higher level LANL2DZ approximation. Key information and answers to the posed questions are shown below. Loose convergence of the RMS gradient for the initial low level approximation as otherwise the iteration will never reach a low enough gradient. As observed from the optimisation summary below in table 9 the structure had been optimised despite the gradient being higher than that of previous calculations signifying a poorer quality minimisation. Electronic convergence of the final structures were produced with greater accuracy due to the increased refinement of the basis set and pseudo-potential. The table below shows information regarding the two optimisation types.

|

Jmol Representations of the structures of the Isomers of Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

∆Table 7 - Jmol Representations of the molecular isomers of Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2.

From the three dimensional representations of the diastereoisomers it can be seen that two of the three hydrogens on each methyl group are in optimal positions when equidistant from a carbonyl oxygen. This is the effect of hydrogen bonding stabilisation that becomes important when steric bulk of ligand is not the limiting factor that decides the energy of the isomers. It can be seen that closer proximity is achieved in the cis isomer due to steric interference of the PMe3 ligands acting to increase the P-Mo-P angle from the expected 90o to the angle of 93.1o and the result is a shorter average O-H distance of 3.3Å in the cis isomer and an average of 3.4Å in the trans isomer. Due to the fact that the cis isomer possessed a dipole moment (trans is centrosymmetric and does not) the hydrogen bonding is also stronger due to the increased electronegativity difference between donor oxygen and acceptor hydrogen, thus this is a more favourable and stabilising interaction.

In comparison of the computed optimised diastereoisomers of the molybdenum title complex the following geometric parameters have been extracted at various points in the optimisation process. Previous to this section illustrative pictures have been given to identify the variables being examined, however in the interest of time, description of the variable in mathematical shorthand has ensued. Literature values have been included in the table and discussion will be continued below.

|

Cis - Optimised to LanL2MB Level |

Cis - Optimised to LanL2DZ Level |

Trans - Optimised to LanL2MB Level |

Trans - Optimised to LanL2DZ Level |

|

----------Bond Lengths------------ |

----------Bond Lengths------------ |

----------Bond Lengths------------ |

----------Bond Lengths------------ |

|

-------------Angles--------------- |

-------------Angles--------------- |

-------------Angles--------------- |

-------------Angles--------------- |

∆Table 8 - Important Parameters for optimised isomers using firstly LanL2MB pseudo potential and basis set, and secondly by LanL2DZ pseudo potential and basis set.

From the above table it can be seen that the two structures when optimised do not perfectly assimilate the point group geometry and standard hybridisation angles that would be expected to be observed. This is of course due to the computational method treating the electronic distribution of the molecules in 3D space and not just along the plane of bonding. The inclusion of hydrogen bonding stabilisation is a clear example of the computational accomodation of these effects. As these molecules are not perfectly identical to their symmetry optimised counterparts and such is try for many molecules in their ground state. It is important at this point to remember before comparison of literature values that the structure obtained is of a molecule in the gas phase. The literature single crystal X-ray diffraction results have been sighted but it must be beared in mind that this calculation may have crystal packing forces that distorts the molecule from the picture obtained here. However the literature value will serve to add credibility to the geometry calculated. Mo-P = 2.52Å; Mo-C = 1.97Å & 2.03Å; C-O = 1.14Å; P-C = 1.85Å&1.79Å; P-Mo-P = 97.5o; P-Mo-C = 90.8o; Mo-C-O 178.0o; Mo-P-C = 116.4o[3].

The values cited in the literature showed very little discrepancy from the computational values when the exact variables that had been expressed in this report were compared with the exact same bonds in the molecular crystal. Packing forces appear not to be an issue for this molecule and a maximum discrepancy of under 5% was observed. The fully optimised results showed a convergence towards the real values from the inputted minimally optimised LanL2MB basis set which were a considerable distance off. The most significant error was observed for the Mo-P which provides evidence for the minimal basis set being not sufficient to adequately describe the electronics of the phosphorus atom. Knowing the literature value for the Mo-P bond and with an extended basis set calculation being run it should be easy to define the effect of adding phosphorus' d- orbitals to its basis set, which has been completed below. As the values for a trans isomer of the exact molecule could not be found the previously found literature values serve to prove that the values are sensible and a good approximation to the real structure has been obtained for both the cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2.

|

Cis-Isomer |

||

|

LanL2MB |

LanL2DZ |

Frequency Analysis |

|

|

|

|

Trans-Isomer |

||

|

LanL2MB |

LanL2DZ |

Frequency Analysis |

|

|

|

∆Table 9 - Summary Windows for the molecular isomers of Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2.

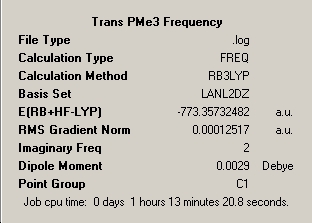

As can be seen from the frequency analysis windows this aspect of the investigation was fairly unsuccessful. Due to the subtleties in getting the molecules to optimise meeting only certain convergence criteria at different stages, it is easy to unerstand that a optmisation may find it's way to maximum point or transition state exhibiting one imaginary frequency. As the energy of the molecule only differed in the last 3 decimal places of the energy then this approximation is sufficiently good. However, if more than one imaginary frequency is returned then the calculation has failed to achieve a stationary point at all and no reliability is afforded to the outcome of the frequency analysis. The optimisation window featured above is for the file uploaded at the top of this section, however the calculation was re-run from scratch but yielded only the same resultant two imaginary peaks for a slightly shorter calculation time of 1hour and 9minutes.

Other ways of checking the accuracy of the calculation had literature values not been found would include the simplifying and homogenising a test molecule (making all ligands the same), with the same molybdenum centre and optimising the structure in small stages and observing the effect on the bond lengths seen. The nature of the test ligand used could then be changed in order to identify a typical range for the binding to a molybdenum centre. Ideally the ligand chosen would include extremes of electronic nature to try to achieve the widest range possible. Following this the metal centre could be changed to one of tried and tested electronic nature where predicted or literature values are easily come by. Comparison of the output of these simple calculations and comparison to any further literature found would obtain evidence for the reliability of unreliability of a result.

The molybdenum complexes were then subjected to full Normal Bonding Orbital molecular orbital analysis. They were submitted to the SCAN using the key calculation instruction shown below.

# freq b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity pop=(full,nbo)

Cis Isomer Frequency

0 1

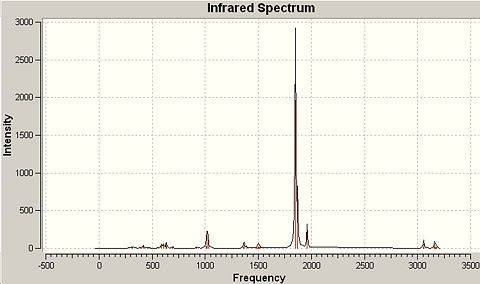

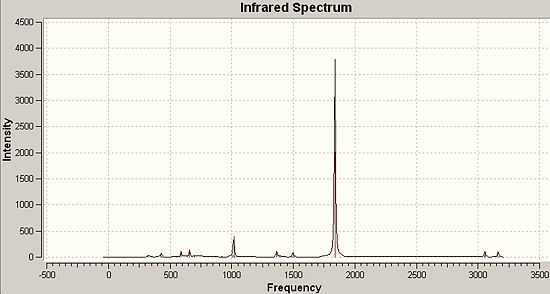

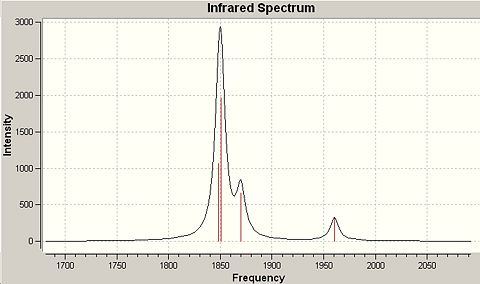

The IR spectra produced by the process are given below and compared to the literature in the following discussion. Literature values were obtained from the Gmelin Database through the MDL Crossfire Commander Interface. It can be seen from the summary above that the optimisation energies of the cis LanL2Dz optimisation and the cis frequency analysis. It can also be seen that the frequency analysis carries an imaginary frequency. This means that the point on the potential energy curve that the frequency analysis is of is of a local maximum or transition state. As the two energies are very close and vary in only the last three decimals (corresponding to an energy difference of 10Jmol-1) the energy difference is insignificant and the frequencies calculated hold for the structures obtained. If the number of imaginary frequencies was greater than one then the point arrived at is not a stationary point and the calculation has failed to reach a reproducible location on the potential energy curve. Trans has currently not reached a correct value need to quickly retrieve the Mo trans off the suite asap and calculate frequencies

|

Infrared Spectra for the molecular isomers of Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 |

|||||

|

Cis Isomer |

Trans Isomer |

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Frequency |

Relative Peak Intensity |

Literature Value[4] |

Frequency (I) |

Relative Peak Intensity |

Literature Value[5] |

|

1960cm-1 |

340 |

2036 |

1838cm-1 |

2003 |

1870cm-1 |

|

1870cm-1 |

666 |

1942cm-1 |

|||

|

1850cm-1 |

1960 |

1920cm-1 |

|||

|

1848cm-1 |

1069 |

1900cm-1 |

|||

∆Table 10 - Infrared Spectral Data for Molecular Isomers.

The vibrations of interest are the carbonyl stretches in the cis and trans forms of the compound. References were found which showed good concordance with the computed frequencies. The obvious difference between the two isomers infrared carbonyl regions is the number of peaks identified, which can all be attributed to the symmetry of the molecule. For centrosymmetric octahedral complexes such as trans-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 all the carbonyl ligands are exactly equivalent to each over when time dependant effects are averaged over the macroscopic IR timescales, hence only one vibrational frequency is obtained with an extremely strong intensity. For the non-centrosymmetric cis version of the complex there are two distinguishable sets of carbonyl groups and for each you would expect to see a symmetry stretch and an asymmetric stretch giving the yielded four peaks cited in the literature.[6]

The pseudo point-group symmetry of the trans-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 is Oh which identifies the high symmetry of the complex. On the Other hand cis-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 has the point group symmetry C2V which is a much lower symmetry group. The integral feature of both spectra is the correct multiplicity of the carbonyl peaks as this is often used in chemical synthesis to follow the progress of a reaction or to identify a geometry. The predicted strong intensity peaks are mirrored in actual infrared spectra and provide a reliable method of structural prediction. The literature values found for the complexes considered do not coincide well with the wavenumbers of the literature, however the predicted peak multiplicity is correct and the source of the error in is likely to be due to a mixture of the slight difference in the optimisation energy for the frequency analysis and the optimised structure and also due to the inclusion of only a minimal basis set for phosphorus in the LanL2DZ pseudo-potential and basis set combination. The inclusion of phosphorus' low lying d-orbitals may well have an effect on the optimisation geometry obtained and therefore the wavenumbers derived from frequency analysis of that optimised structure. In an effort to probe the approximate percentage difference to the energy that the inclusion of d-orbitals into the basis set, the unoptimised trans-isomer was re-input having manipulated the Gaussian input file manually to include the d-orbitals on phosphorus. If time had allowed the whole process would have been repeated to include the phosphorus d-orbitals and to therefore derive the actually differences in the frequencies of the IR spectrum. Upon inclusion of the d-orbitals of phosphorus (or any improvement to the pseudo-potential and basis set utilised) would be expected to have the effect of forcing the wavenumbers of the carbonyl peaks to converge upon the literature values. This would involve the spacing between the peaks equilizing relative to their current spacings and reducing the overall range of wavenumbers observed.

The Hartree energies produced by the optimisation suggest that there is a difference in energy of 7.7kJmol-1 in favour of the more stable cis isomer. This would suggest that the cis structure is stabilised by hydrogen bonding from the oxygen lone pair to the methyl hydrogens more so in the cis isomer than in the trans isomer possible reasoning for this is discussed above.

Fine-tuning of the isomers in terms of energetics could be carried out in order to stabilise the more catalytic isomer over the less useful one. If for example as in this case it was desired that the less stable trans isomer was required it is predicted that increasing the steric bulk of the ligand by exchanging P(Me)3 for P(Ph)3 would favour the largest groups being as far apart as possible favouring the trans over the cis isomer as the hydrogen bonding stabilisation is not significant compared to the destabilisation felt from the steric repulsions. This theory was tested by inputting the two diastereomeric isomers of the titled molybdenum complex for P(Ph)3 to be calculated using the LanL2MB pseudo-potential and basis set combination.

Results of Extended Work

The aim of this short extension was to observe the effect of adding large stericall bulky lingads in terms of the molecule energy observed. It is postulated that having increased the size of the ligand hydrogen bonding stabilisation will become less significant and perhaps the trans isomer will become the more stable of the two as a result. The summary windows for the two diastereomeric molybdenum carbonyl complexes were calculated coordinated to two triphenylphosphine groups are shown below.

From this it can clearly be seen that the energetic favourability is now in favour of..... by approximately......kJmol-1

The use of an extended basis set was also carried out however time did not allow for the consideration of the findings through a combination of busy servers and illness. An exemplar extended basis set optimisation has been uploaded here: [5]

Part 3 - Ammonia

Optimisation Symmetry and its Effects

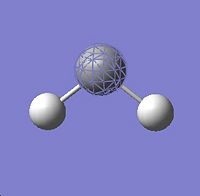

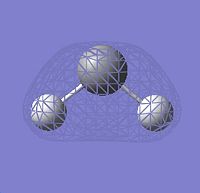

In the first part of this section we will consider the effect on the optimised structure of changing the symmetry of the inputted file. This investigation will answer the question 'how important is it to know the symmetry of a molecule in which only the molecular formula is known. For the simple molecule NH3 it can be imagined that the molecular formula may take the form of the high symmetry trigonal planar formula taking on the point group of D3h. Another option is that all bond lengths may not be identical and therefore the point group symmetry of the molecule may be C1. Of course the reality is that the tool of hybridisation leads to the correct geometry with a long pair occupying a non-bonding sp3 orbital which forces the molecular geometry into trigonal pyramidal geometry due to electron-electron repulsions and of course the true point group C3V. Of course these three point groups are linked together mathematically with D3h being the high symmetry group in the chain, C3V a lower symmetry sub group, and C1 a low symmetry sub group in the chain.

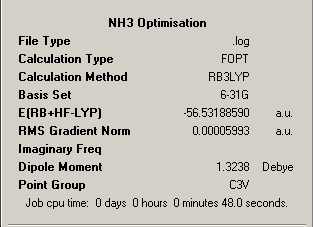

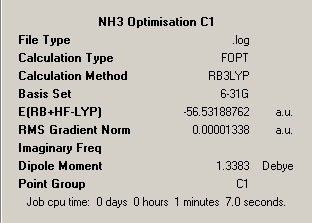

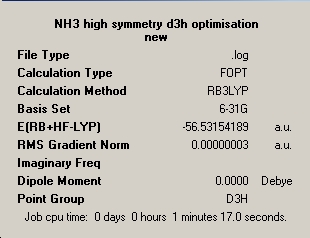

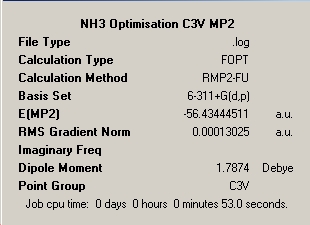

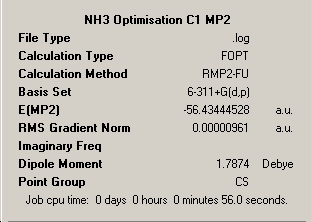

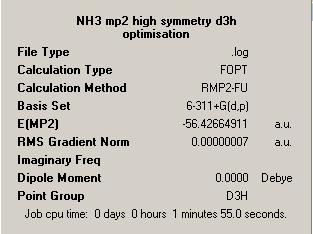

Below is a table of the summary windows for the B3LYP and 6-321G optimisation of each constrained symmetry. Discussion of the implications continues below.

|

Ammonia Symmetry Summary Captions |

||

|

C3V |

C1 |

D3H |

|

|

|

∆Table 13 - Summary Windows for the Variable symmetry of NH3.

|

Ammonia Output Orientations |

||

|

C3V |

C1 |

D3H |

|

1.01Å = B1 = B2 = B3 |

1.01Å = B1 = B2 ≠ B3 |

A1 = A2 = A3 = 1.00Å |

∆Table 14 - Geometric output (optimisated parameters for each distinct input geometry.

All structures can be seen be have been optimised effectively possessing a final gradient below 0.001. The difference between the different symmetry inputs is apparent from the realised geometric parameters. Shortest bonds are observed for the higher symmetry planar D3h and C3V has slightly shorter bonds than C1. It is also worth noting that if symmetry was requested to be conserved through the calculation, resultant equal parameters can't be realised in the optimised structure if they were not equal in the input geometry. This can be seen for the optimised C1 parameters where although very close in proximity the bond or angle parameters can't be equal. In that respect, unless symmetry is ignored then symmetry must be conserved through the calculation process. In comparison of the optimised angles of the non-planar geometries, the C1 angles are smaller than the C3V angles and as mentioned the angle parameters are equal in the C3V molecules, whereas the C1 angles can't be. The D3h molecule unsurprisingly has all 'like' parameters equal.

This process clearly shows that the conventional geometries of the molecule are required to be correct in order to obtain the most rapid estimate of the geometry. In many cases a higher symmetry point group will obtain a more rapid result however this is only the case when the high symmetry geometry is the VSEPR derived structure. This shows that a knowledge of the valence electronic configuration of the atoms in the molecule being considered is required to shorten computational timeframes and to therefore save money. A shorter calculation time is observed for the C3V point group geometry in this case as it is the VSEPR model for the geometry of the molecule. The longest calculation time is observed for the molecule with the least symmetry as if the symmetry is know the method can work to stricter computational rules. The percentage difference between the calculation times of 48 seconds for C3V and 67 seconds for C1 of 40%%. Therefore it is worth noting that working from a molecule with very low symmetry takes significantly longer than working from a pre-defined and constrained point group however the calculation time can be further reduced by knowing more about the expected symmetry of the molecule. The implication of this is that the higher order is the symmetry of the molecule the more defined are the rules that dictate the course of the reaction and more defined are the symmetry of the functions that make up the basis set.

If a high symmetry structure is input into Gaussian the symmetry must be confined and optimising the molecule will be severely constrained. This can be a good thing under some applications if symmetry needs to be conserved, however is can also have the adverse effect of not allowing the structure to fully optimise and reach a gradient that is low enough to converge to a minimum energy.

As can be seen from the output energies, featured in Table 14 in kJmol-1, the C1 geometry is predicted to be the lowest energy structure at the level of optimisation used. It is 731Jmol-1 more stable than the D3h geometry showing that the non-bond pair of electrons are being considered in the basis set utilised. The C1 geometry is rather surprisingly 36Jmol-1 more stable than the C3V geometry although this is a low number. The source of this added stabilisation may be in terms of increased disorder (i.e. entropy favoured), however the energy difference is not significant as thermal energy at room temperature accounts for approximately 2.5kJmol-1 of available energy. This is evidence for the fact that it is facile for the C3V symmetry to distort to C1 interchanging rapidly whereas the realisation of the more energetically unfavourable high symmetry D3h point group , which is entropy disfavoured, has a much higher activation barrier that corresponds to an increase in temperature of nearly 90K based on purely thermal agitation. However it is known that the inversion of ammonia is a purely quantum mechanical phenomenon based on the hydrogen atoms quantum tunnelling through to the other side of the molecule through the D3h symmetry. The energy values quoted correspond to the activation energies required to invert the molecule.

Clearly the dipole moment results are a consequence of the differing geometric structures and therefore different approximated electronic distributions. The RMS gradient may optimise to slightly different values as the potential energy surface defined for each input structure is slightly different. In evaluation of this analysis, the important messages is to be aware of the errors induced by obtaining structures of slightly different symmetry and energy and to do all possible to reduce computational timeframes.

Changing method and basis set to MP2 and 6-311+G (d,p)

'Pre-optimising' structures before using the improved method and basis set described above is a conventional tactic for reducing electricity costs and time in computational chemistry. Molecules in this section were not pre-optimised as the full calculation time was required to contrast the lower and higher level approximations. In this section we will be concerned with the increase in computational time, although ammonia is a small molecule and doesn't take much longer to process, it is the percentage increase that will offer guidance in the future when much more complex molecules are considered. As in the previous section the same three geometries were considered and the summary windows for each has been features below in table 15.

|

Ammonia Symmetry Summary Captions |

||

|

C3V |

C1 |

D3H |

|

|

|

∆Table 15 - Summary Windows for the Variable symmetry of NH3 calculated under new basis set.

Firstly, it is of notes that all structures have optimised having a RMS gradient of less than 0.001. The calculations can be seen to have taken less time than the DFT B3LYP calculations with a better basis set. The difference in calculation times between the longest (C1) and the shortest times (C3V) for the MP2 method is 3 seconds or 5.7%. It is notable that the same order in relative amount of time taken is not observed and this calculation process seems to favour lack of defined symmetry over too highly constrained symmetry with a small percentage difference of 1.8%. The decrease in calculation time in comparison to the longer B3YLP method used earlier is an average of 14.57% despite the increase in complexity of the calculated basis set. However if the geometry of the molecule is known then the B3LYP method proves to be the faster by 10.4%.

In the case of the new basis set the energy barrier to inversion, as defined earlier, is 16.58kJmol-1. In comparison of the two methods and the literature values for inversion of ammonia (24.3 kJmol-1) the MP2 method obtains a better result even though it has a lower average calculation time. The percentage increase in the accuracy achieved by the method over the B3LYP method is 65%. This is a huge value and emphasises the need to choose carefully which calculation method you use for which type of calculation as for example MP2 is much better than B3LYP at predicting experimental relative energy differences between isomeric molecules.

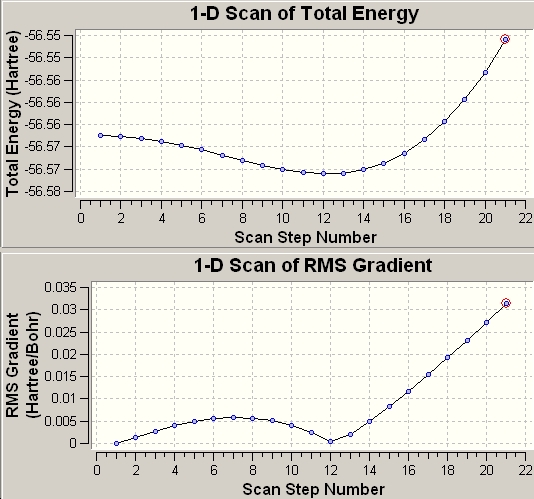

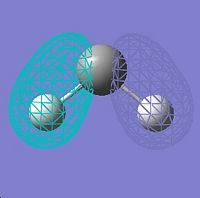

Inversion

So far we have constructed a symmetry defined route, with a high activation barrier, by which ammonia can invert its structure. The aim now is to connect the energies of the intermediate phases between the calculated point group symmetries. 'A scan' is a reference eigenvalue used to plot such a path which works by controlling one variable with respect to the optimised geometry and allowing the other variables to optimise. This scan can be plotted to yield the inversion energy profile. In this case the controlled variable is the bond lengths (R1) and the variance is seen in the angles that move the hydrogen atoms in an umbrella motion reaction coordinate is the movement of the hydrogen atoms in an umbrella motion[7].

The 'scan' is computed and published in the log file of the optimised structure and this allows the potential energy surface of the mechanism to be plotted directly. The 'scan' for file given is shown below and corresponds to the optimisation plot in figure 6.

1 2 3 4 5

EIGENVALUES -- -56.56750 -56.56765 -56.56806 -56.56874 -56.56962

R1 .99867 .99867 .99929 1.00002 1.00102

A1 90.00000 88.00000 86.00000 84.00000 82.00000

T1 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000

6 7 8 9 10

EIGENVALUES -- -56.57067 -56.57182 -56.57300 -56.57410 -56.57505

R1 1.00232 1.00388 1.00570 1.00776 1.01005

A1 80.00000 78.00000 76.00000 74.00000 72.00000

T1 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000

11 12 13 14 15

EIGENVALUES -- -56.57572 -56.57603 -56.57585 -56.57509 -56.57365

R1 1.01254 1.01525 1.01814 1.02124 1.02454

A1 70.00000 68.00000 66.00000 64.00000 62.00000

T1 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000

16 17 18 19 20

EIGENVALUES -- -56.57142 -56.56833 -56.56431 -56.55930 -56.55321

R1 1.02805 1.03178 1.03574 1.03995 1.04447

A1 60.00000 58.00000 56.00000 54.00000 52.00000

T1 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000 120.00000

21

EIGENVALUES -- -56.54594

R1 1.04941

A1 50.00000

T1 120.00000

∆Table 15 - Optimisation plot showing the controlled approach of a transition state in the inversion mechanism.

This process can easily lend itself to following a reaction dynamic and this is how reaction profiles are tested and derived computationally.

Vibrational Analysis

The vibrations of C3h molecules are linked to those of the D3h point group membership such as earlier considered BH3. The vibrations observed in a molecule are highly symmetry dependant and as the two point groups are mathematically linked to each other, with D3h being the main group and C3V being the sub-group, similarities will be seen between the realised spectra.

|

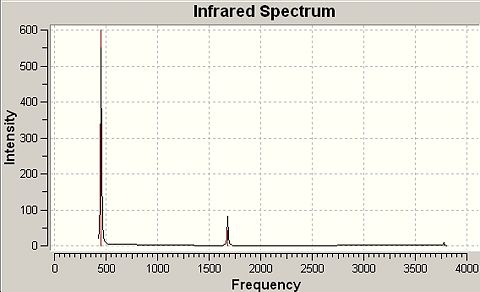

Infrared Spectra for NH3 modelled in D3h and C3V Point Group Geometries |

||||

|

D3h |

C3V |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Frequency |

Relative Peak Intensity |

Literature Value[8] |

Frequency |

Relative Peak Intensity |

|

-318cm-1 |

849 |

937cm-1 |

452cm-1 |

599 |

|

1641cm-1 (degenerate) |

55 |

1626cm-1 |

1680cm-1 (degenerate) |

42 |

|

1641cm-1 (degenerate) |

55 |

1627cm-1 |

1680cm-1 (degenerate) |

42 |

|

3636cm-1 |

0 |

3337cm-1 |

3575cm-1 |

0.0 |

|

3854cm-1 (degenerate) |

20 |

3343cm-1 |

3776cm-1 (degenerate) |

7 |

|

3854cm-1 (degenerate) |

20 |

3343cm-1 |

3776cm-1 (degenerate) |

7 |

∆Table 16 - Infrared Spectral Data for Ammonia Point Group Isomers.

The C3V frequency analysis yields six positive frequencies. The D3H frequency analysis yields five positive frequencies plus one negative frequency that defines the transition state structure. It is clear from the spectrum that the same vibration in each point group appears at very different wavenumber in the D3h spectrum as it does in the C3V spectrum. These vibrations have been identified in single rows in the table above.

As discussed previously, the C3V structure is the ground state structure which always has all positive frequencies[9]. The value of the negative frequency (imaginary) that defined the D3h structure as a transition state is -318cm-1. From the form of the vibrational modes present for each molecule, the vibration that follows the inversion profile described in a previous section of the report was -318cm-1 (the imaginary frequency) for D3h and 452cm-1 for C3V.

In comparison of the literature values and the predicted wavenumbers for the infrared absorption of ammonia there is an average discrepancy of The calculated frequencies are not especially good when you consider the fact that the vibrations that there is an average error on each of approximately 20%. The results do show a definite tendency towards the C3V over the transition state geometry of the D3h.

Mini-Project

Introduction

Original interest for this project arose in the area of the unusual electronic structure that was a characteristic of the divalent carbenes, alkylidenes, metal carbenoids and their heavier congeners. The starting point was to investigate the ability of the computational approach to accomodate this usual type of electronic configuration and testing the computational function of characterising the multiplicity of the ground state of such species. This will involve investigating the well-known Dewar-Chatt-Duncanson model for metal-carbene double bond character and whether the relatively simple calculation modes can account for these bonding orbital interactions. Two well know carbenoid species will be considered varying in substituents and metal centre and the effect of back-bonding will be considered.

Many ideas for this section failed on the basis of sheer computational time scales even when attempting the lowest level Hartree-Fock and DFT methods on minimal basis sets and loose convergence criteria. This is due to the level of electronic complexity in the molecule and the poor treatment of unconventional bonding. This was a problem when considering carbenoid species containing Cp rings. For this reason many ligands have been simplified to conventionally bonding ligands which are better and rapidly treated by the computational approaches that time permits for this section. Many of the scans had to be submitted to the overnight SCAN due to the fact that errors occurred when submitted to Gaussian on the student laptops. This was due to the processing power required to run the calculations and caused long time delays in obtaining the results.

Comparison of Methylene and Silylene

The files could not be published to D-space and so the optimised files have been linked here as txt files: Silylene Frequency Analysis File[6]; Methylene Frequency Analysis File[7]

Geometry Analysis

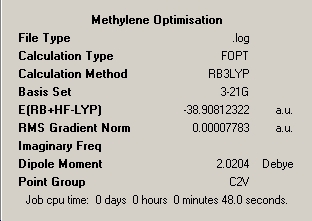

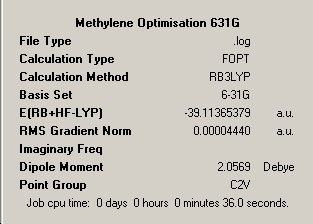

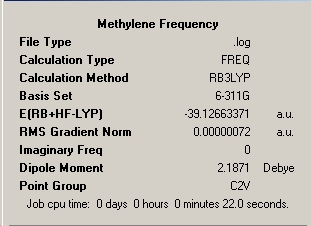

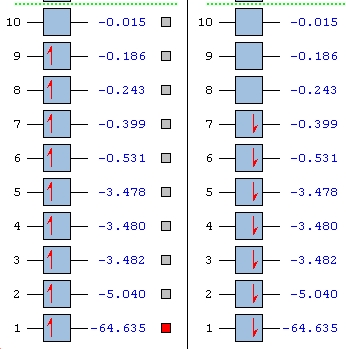

The first stage of this mini-project was to consider the well publicised differing ground state structures of the important transient reaction intermediate methylene and the less common silylene analogue. The sequence of optimisation of the two structures has been illustrated below via inclusion of the optimisation summaries for each step which has been commented on. For methylene all elements are in the first row of the periodic table and therefore use of pseudo-potential is unnecessary. Therefore this molecule will be optimised utilising B3LYP method; 3-21G and 6-31G basis sets for 'pre-optimisation' and final optimisation utilising the 6-311G and frequency analysis and full molecular orbital analysis was executed from this optimised structure.

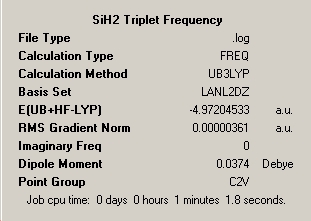

∆Table 17 - Summary Windows for the Calculations carried on on methylene and silylene

All locations probed by each method has optimised the structure to a gradient under 0.001 Hartree, and none of the points on the potential energy curves that were frequency analysed had any imaginary frequency which identifies the optimised structure as a genuine minimum stationary point on the potential energy curve.

For the silylene the input geometry had to be specified as triplet in nature due to the knowledge that for silylene the triplet ground state is more stable. A species will adopt a triplet ground state if the HOMO orbital is a degenerate set that is half occupied in the case of a doubley degenerate HOMO set. This statement is in accordance with the Hund's first rule of multiplicity which states that if it is possible to a species will seek to maximise its spin and the degeneracy allows this to happen without suffering an energy debt to promote an electron to the next highest energy level. It could be thought that by this reasoning methylene may adopt a triplet ground state as open the triplet state is lower in energy, however the formation of a triplet ground state would cause severe destabilisation of the molecule due to polarisation of the electronic distribution in a non-polar molecule. This problem is exhasibated by the small penetrating molecular orbitals of methylene in comparison to the larger more diffuse orbitals of silylene that can better accomodate the polarised electron cloud which is held less tightly to the nucleus. A clear aim of this section will therefore be to directly compare the sizes of the molecular orbitals of methylene and silylene.

The geometries of the two complexes were then compared through the optimisation route as seen below in table 17 and discussion continues below.

|

Methylene Geometric Parameters |

||

|

3-21G 'Pre-Optimisation' |

6-31G 'Pre-Optimisation' |

6-311G Optimisation |

|

B1 = B2 = 1.13Å |

B1 = B2 = 1.13Å |

B1 = B2 = 1.12Å |

|

Silylene Geometric Parameters |

||

|

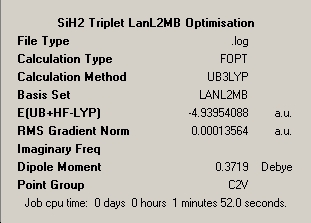

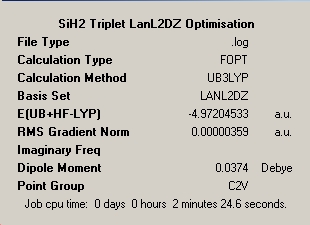

LanL2MB 'Pre-Optimisation' |

LanL2DZ Optimisation |

Frequency Analysis |

|

B1 = B2 = 1.55Å |

B1 = B2 = 1.49Å |

B1 = B2 = 1.49Å |

∆Table 18 - Comparison of the simple geometries of methylene and silylene at varying points of optimisation

The above table shows that the methods very fairly close to the literature values however the approach could doubtless be improved by increasing the basis set orbitals considered. In both cases the method seems to be converging upon the literature bond length however also in each case it is true that the optimum bond angle is not be converged upon which may suggest the more amenable method is available as the basis set used for methylene is sufficient for the simple hydrocarbon bonding. On the other hand it may point towards a stabilising factor that is acting upon the molecule that can't be treated by this particular computational method and basis set, as it is true that a similar factor would also be present in the silylene molecule that could result in a similar effect. This point will be revisited upon molecular orbital anaylsis in order to attempt to identify the factor that is causing the discrepancy or whether it can't be resolved. These result seems to show that a minimal basis set is also sufficient for silylene and its low lying d-orbital do not significantly participate, so they will not be considered.

Frequency Analysis

Finally, as featured earlier, a frequency analysis was run for the two molecules including an analysis of the important molecular orbitals and the contrasts between the two. Dealing first with the simple spectra and vibration that derive from the C2V point group symmetry of each molecule.

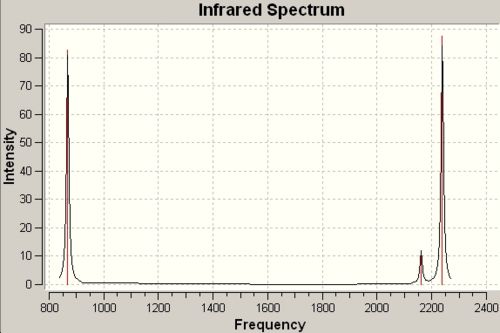

|

Infrared Spectra for Methylene and Silylene derived from C2V Symmetry |

||||

|

C2V Silylene |

C2V Methylene |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Frequency |

Relative Peak Intensity |

Literature Value[12]& Assignment |

Frequency |

Relative Peak Intensity |

|

868cm-1 |

82 |

995cm-1 C-H Bend |

1406cm-1 |

4.2 |

|

2161cm-1 |

12 |

1973cm-1 C-H Symmetric Stretch |

2794cm-1 |

148 |

|

2238cm-1 |

57 |

1992cm-1 C-H Assymetric Stretch |

2862cm-1 |

127 |

∆Table 19 - Infrared Spectral Data for methylene and silylene congeners.

As the two congeners above have the same point group symmetry they possess the same vibrational motions in their IR spectra, however as can be observed there is a massive difference in the predicted wavenumber's observed for each vibration. The fit to the spectral data is not great even though the method has clearly optimised to a minimum energy that is equal to the optimisation energy for the final optimisation in the sequence. The lack of account for d-orbitals in the approximation may go some way to explaining why the infrared wavenumbers are quite a lot way off even though they show the expected pattern of absorptions.

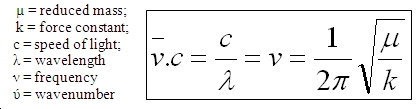

The only difference between the molecules is the bond strengths involved in the binding that will change the predicted frequency of the vibration. In this respect an empirical derivation can be made as to the relative strength of the Si-H bond in comparison to the C-H bond. The expected result is that the bond will be stronger for C-H due to their more similar sizes and electronegativity difference participating in an almost fully covalent bond. Taking the lowest energy peak from each spectrum and comparing the wavenuber for the same bending vibrational motion a peak spacing of 538cm-1. The relationship that links frequency to force constant (bond strength) is shown below:

From this it can be seen that frequency is proportional to k-1/2. In this way manipulating the express leads to the conclusion that the C-H bond is approximately 3.5x10-6 times the strength of a Si-H bond. The average value of the three peak spacings is approximately 2.8x10-6.

Molecular Orbital Analysis

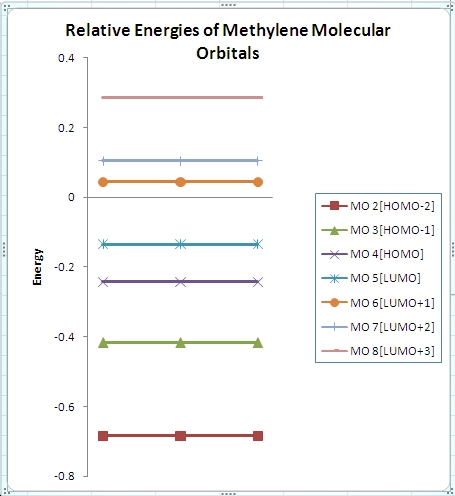

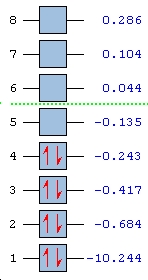

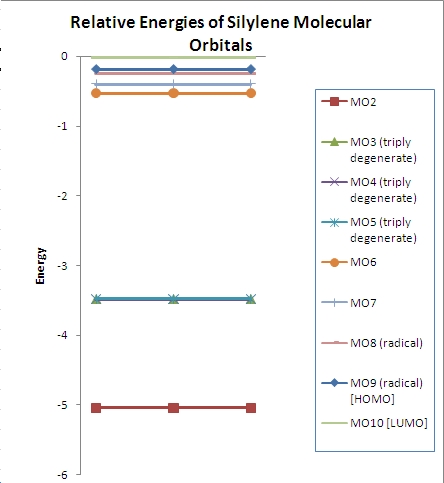

For the frequency analysis the full molecular orbital diagram for methylene and silylene has been contrasted and plotted below:

|

Molecular Orbitals for Singlet Methylene |

||||

|

HOMO - 3 |

HOMO - 2 |

HOMO - 1 |

HOMO |

LUMO |

|

|

|

|

|

∆Table 20 - Visual Representations of the Molecular Orbitals of Methylene

|

Molecular Orbitals for Triplet Silylene |

||||

|

HOMO - 3 |

HOMO - 2 |

HOMO - 1 |

HOMO |

LUMO |

|

|

|

|

|

∆Table 21 - Visual Representations of the Molecular Orbitals of Silylene

Difficulties were faced as the LanL2DZ optimised geometry of silylene did not produce a downloadable checkpoint file from the SCAN server so the file had to be manually input again. This took time and the eventually a means of obtaining the checkpoint file was found and the MO orbitals obtained for SiH2.

Below is featured a plot of the relevant energy levels and a plot of the occupancy of each of the orbitals that was mapped. It can be seen that the promotion energy needed to promote an electron from the HOMO orbital to the LUMO orbital is 0.108Hartree. This corresponds to an promotion energy of 230kJmol-1, which is very high and the energy debt caused by the pairing of the HOMO electrons is much less than the promotion energy necessary for intersystem crossing to occur.

∆Figure 4 - Molecular Orbital energy diagram plots as visual reasoning aids.

With an estimated 0.108Hartree or 230kJmol-1 first excited state (S1) promotion energy for the singlet methylene species it is easy to understand why the methylene ground state configuration prefers to pair electrons in the HOMO orbital as opposed to promoting to the next highest level. This provides good evidence for the reasoning behind the observation that methylene is a singlet ground state species. A typical pairing energy may on in the order of a couple of kJmol-1 and is certainly very significantly less than the promotion barrier.

∆Figure 5 - Analogous Molecular Orbital Energy Diagrams for use as visual aids.

With an estimated 0.157 Hartree or 334kJmol-1 difference between the diradical energy levels (T1 ground state) promotion energy for the triplet silylene is no smaller than that for methylene. However when axamining the whole picture of the relative energies of the molecular orbitals it can be seen that there are much larger energy gaps of approximately 5 Hartree. When bearing in mind the filling of the orbitals the HOMO-LUMO region is hiding inside a bunch of orbitals that are close together in energy with respect to the largest energy gaps. Therefore if a molecule has a electron which must fill high energy levels then it is more favourable to avoid spin pairing and the formation of a triplet state which is more stable than the ground state has been formed. In this species it is apparent that the compound can avoid the extra electron-electron repulsions by promoting and undergoing a rapid rate of intersystem crossing to shut of the S1 decay path back to the S0 the methylene ground state configuration prefers to pair electrons in the HOMO orbital as opposed to promoting to the next highest level. This provides good evidence for the reasoning behind the observation that methylene is a singlet ground state species. A typical pairing energy may on of the order of a couple of kJmol-1 and is certainly significantly less than the promotion barrier.

Evalutation

The procedure has been very successful in providing circumstancial rationalisation for the differences in the ground state structures of each compound. Although the molecule is extremely simple if is not a conventional structure with a divalent carbonyl and some intrigue is added to the following section in which some good experimentally agreeing values can be extracted. As these compounds are under large amounts of scrutiny in the chemical world due to their importance as transient intermediates. As silylene is less transient than methylene then spectroscopy has been able to be carriod out The literature values added credibility to the optimised structures obtained and the testing could have been increased further in accuracy to encroach even further on literature geometric values.

IR spectral data was identified in a chemical physics journal which did not agree brilliantly with the predcited results. This suggested that their is a better computational means to derive the spectral properties of interest for a molecule. In comparison of the molecular orbitals of each of the congeners it can be said that when viewed under an equal isocontour value of 0.1 that it was not observed as proposed that silicon atom carries softer diffuse orbitals. Since this approach has been seen to be so successful in dealing with methylene and silylene things are promising for the carbenoids being considered.

Comparison of Two Carbenoid Species

Introduction

The two reagents considered in this section are; a derivative of Tebbe's reagent and Grubbs' (first generation) catalyst. The nature of their electron distributions has important implications for their properties and hence for their applications in synthetic chemistry. Both species are said to have a doublet electronic multiplicity, however in reaction they may behave as if singlet or triplet in nature. Doublet refers to the olefin type metal-carbon double bond that influences the electronic structure.

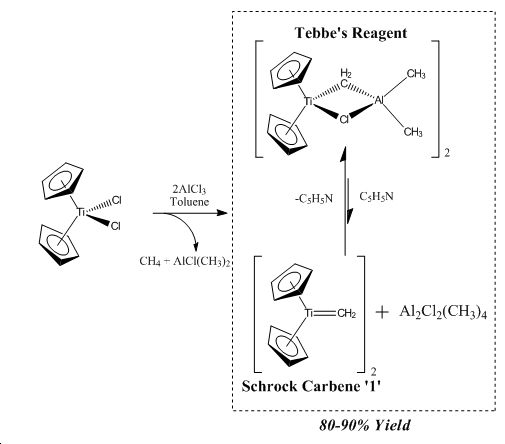

Tebbe's reagent is a complex based on group 4 Titanium in its +2 oxidation state. Tebbe's reagent exists in equilibrium with a Schrock carbene (1) with dimerised AlMe2Cl2 which can be pushed to favour the formation of Tebbe's reagent by adding Lewis basic pyridine, as seen below in figure 6. Tebbe's reagent is the stable state of the active Schrock carbene (1) that is used for methylenation of carbonyls.

Tebbe's Reagent is an important reagent, being an indirect source of a reactive carbene species that shows favourable reactivity towards olefination of carbonyl compound, proceeding through a proposed oxatitanacyclobutane intermediate. This reaction is driven by the favourable formation of the strong Ti=O bond in the yielded side-product and this favourable formation is termed that Titanium has high oxaphillicity. Tebbe's reagent was the first complex to exhibit a methylene bridging bond to a transition metaland a main group metal[13]. As the bridging alkyl group is not easily modelled computationally as with the cyclopentadienyl groups the species being studied is 1, which will give added insight by being directly related to the simple carbene that was considered in the section above. The cyclopentadienyl ligands will be modelled using PMe3 ligands which are regularly used to model more complex ligands in a simplified fashion.

The reagent has analogous effect to the Wittig reaction however it has clear advantages of having chemistry based on a transition metal complex which are cited as being more efficient, especially for sterically encumbered carbonyls and furthermore, the Tebbe reagent is less basic than the Wittig reagent and hence does not give unwanted products formed by β-elimination. Although separation is more productive some useful work has been done using the reagent in-situ[14][15][16].

∆Figure 6 - Formation and equilibrium allowing formation of 1

This work will also include examination of the molecular orbitals and frequency analysis of 1, and examination of the moelcular orbitals will lead to the identification of the equatorial binding orbitals that allow bent metallocenes to form and also the change in Cp binding orbitals to facillitate this change.

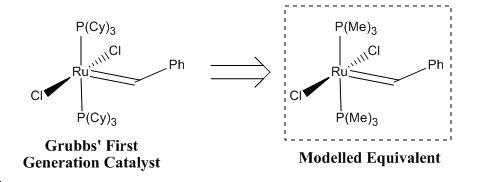

Grubbs catalyst is an alkylidene carbenoid with a group 8 ruthenium metal centre in its +4 oxidation state. It is termed an alkylidene the methylene group behaves as a triplet carbene would when reaction takes place. Grubbs' catalyst is a olefin metathesis catalyst and performs such reactions with high versatility and accomodation of sensitive functional olefin substituents. The catalyst is also employable in a wide range of solvents. The correct structure of the ligands of the Grubbs first generation catalyst are cyclohexane structures, which are even more amenable to the simplification to PMe3 ligands for this modelling exercise. This is summarised pictorially below in figure 7.

∆Figure 7 - Form of Grubbs' First Generation Catalyst and modelled version

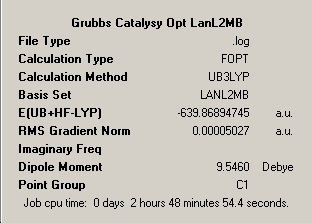

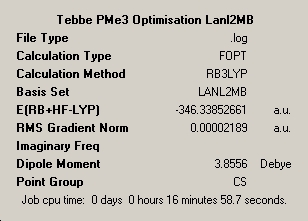

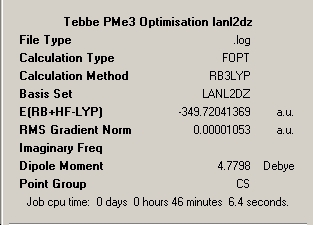

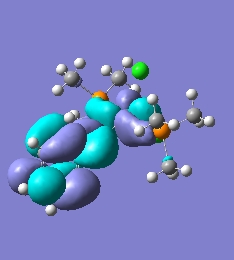

Both molecules were optimised used the B3LYP and LanL2MB 'pre-optimisation' followed by optimisation using the B3LYP and LanL2DZ pseudo=potnetial and basis set combination as it has proved to be effective with such molecules in the treatment of the Molybdenum complexes seen earlier. A Jmol representation of each of the final structures has been included and the optimised variables that make up the structure have been taken from the optimisation log file and summarised below.

Geometry Analysis

Again like in the first section of the mini-project the optimised structure's optimised variables have been published and compared to literature values. The optimisation pathway has been included by featuring the summary windows for each stage of 'pre-optimisation' and optimisation. Full molecular orbital analysis was executed from the optimised structure the summary of which has been included below.

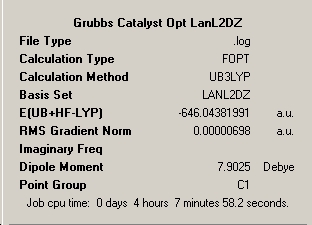

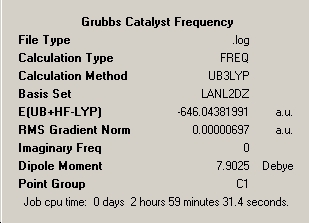

∆Table 22 - Summary Windows for the Calculations carried out on Grubbs Catalyst and Tebbe's Reagent

All locations probed by each method has optimised the structure to a gradient under 0.001 Hartree. However the frequency optimisation of Schrock alkylidene was computed for a non-crucial point as determined by the present of more than one imaginary frequency. A further attempt was made using fine convergence criteria to analyse the frequencies however the same result was obtained in both cases. Analysis of the spectrum produced by this unfortunate should still be possible from the ouput and via consideration of likely literature values. The Grubbs frequency analysis contains no imaginary frequencies which illustrates that the frequencies were calculated for one of the points on the potential energy curves that identifies the optimised structure as a genuine minimum stationary point on the potential energy curve.

In terms of the energies, as no conclusion can be drawn from energies obtained via different methods or basis sets, all that can be done is to compare which of the two carbenoids is the more stable. The energy differences between the structures at the LanL2MB level is 6.2x105kJmol-1, at the LanL2DZ level the difference is 6.3x105kJmol-1 and the frequency analysed positions are 6.2x105kJmol-1 all in favour of the more stable Grubbs Catalyst. Simply compare the realised energies from the same method and basis set in a brief sentence

The geometries of the two complexes were then compared through the optimisation route as seen below in table 17 and discussion continues below.

|

Grubbs Catalyst Geometric Parameters |

||

|

LanL2MB 'Pre-Optimisation' |

LanL2DZ Optimisation |

|

|

Ru=C = 1.76Å |

Ti=C = 1.74Å |

Ru=C = 1.85Å |

|

Schrock Alkylidene 1 Geometric Parameters |

||

|

LanL2MB 'Pre-Optimisation' |

LanL2DZ Optimisation |

Literature Values |

|

Ti=C = 1.92Å |

Ti=C = 1.89Å |

Ru=C = 1.85Å |

∆Table 23 - Comparison of the geometries of Grubbs catalyst and 1 at varying points of optimisation

The above table shows that the methods are fairly close to the literature values however the approach could doubtless be improved by increasing the basis set orbitals considered ad using a better modelling pseudo-potential. In both cases the method seems to be converging upon the literature bond length however also in each case it is true that the optimum bond angle is not be converged upon which may suggest the more amenable method is available as the basis set used for methylene is sufficient for the simple hydrocarbon bonding. On the other hand it may point towards a stabilising factor that is acting upon the molecule that can't be treated by this particular computational method and basis set, as it is true that a similar factor would also be present in the silylene molecule that could result in a similar effect. This point will be revisited upon molecular orbital anaylsis in order to attempt to identify the factor that is causing the discrepancy or whether it can't be resolved. These result seems to show that a minimal basis set is also sufficient for silylene and its low lying d-orbital do not significantly participate, so they will not be considered.

Frequency Analysis

Finally, as featured earlier, a frequency analysis was run for the two molecules including an analysis of the important molecular orbitals and the contrasts between the two. Dealing first with the simple spectra and vibration that derive from the point group symmetry of each molecule if any is present.

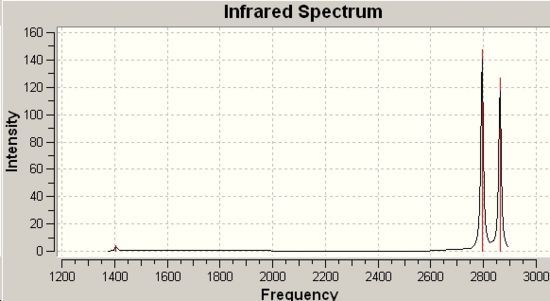

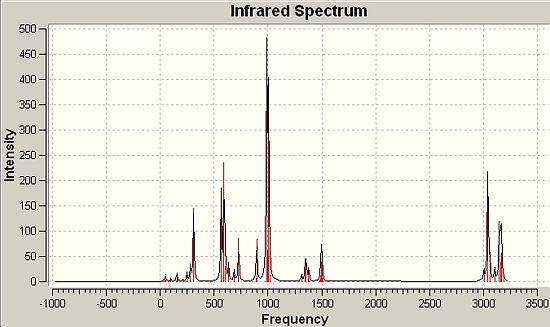

|

Infrared Spectra for Schrock Alkylidene 1 and Grubbs Catalysis |

||||

|

C1 Grubbs Alkylidene |

CS Schrock Alkylidene 1 |

|||

|

|

|||

∆Table 24 - Infrared Spectral Data for Grubbs Catalyst and 1.

Infrared spectra will not be assigned in depth only significant peaks will be assigned and analysis taken from it regarding backbonding and empirical strength of bonding due to difference in metal centre. The expected empirical result would be that due to backbonding to the methylene group in each case electron density would be removed from the metal centre, strengthening electronic donation from the phosphine bond which would increase the bond force constant k and therefore reduce the wavenumber the vibrations are observed at for the phosphine group. Backbonding to the empty pz orbital on the methylene group (as identified in the previous section would destabilise methylene substituent bonds, lowering the bond force constant and increasing the wavenumber of the peaks observed in the IR spectrum. This section will rely heavily on finding appropriate literature values to retain reliable evaluation as the molecules are intrinically different and therefore not directly comparible. The two molecules will however be epitimised by their intrinsically different electronic nature and guiding principle will be the different in degree of backbonding that the two molecules exhibit. The Ruthenium centre is more electron rich than the Titanium centre and therefore more backbonding behaviour would be expected of the Ruthenium centre. The main bonds that will be focused on in this analysis is the phosphine bonds that are common to both molecules.

As can be seen from the results.....

Molecular Orbital Analysis

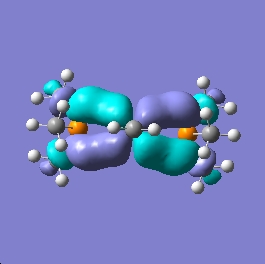

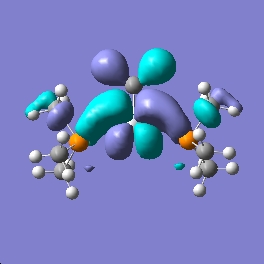

Shown below are the MO representations for the HOMO and LUMO orbitals of 1 and Grubbs' Catalyst.

1

It can be seen from the representations that the HOMO and LUMO orbitals of the titanium based molecule (assumed to show the greatest donor-acceptor nature) do not show the correct symmetries to be effective at back bonding, with the metal based HOMO orbital showing clear delta-bonding symmetry and the methylene based LUMO orbital showing distinct pi-symmetry. However it is likely that because an orbital resembling a pi-star orbital has been identified it is likely that there will be a couple of orbitals that are able to weakly donate and increase the bond order of the metal-methylene bond into the double bond range. Minimal net interaction will occur between the HOMO and LUMO orbitals in the region of the methylene group and therefore the bond order and frequency of vibration would be expected to show a mid-range value with respect to the literature. Also with reference to the geometry of the bonding the metal carbon double bond would be expected to be fairly elongated due to the weak pi donation attained.

This is indeed the case as the prediced bond length of the Ti=C bond shows good concordance with the literature and agrees with the analysis that minimal backbonding will occur.

Grubbs Catalyst