Rep:Mod:god2212

Daniel Godfrey - 21/01/2009 - Organic Computational Laboratory

Introduction

Through the course of this project, reactions will be mapped using a range of computational techniques including molecular mechanics, semi-empirical and density functional molecular orbital theory. This process will in the most part take the form of computational analysis of reactants and products of cited reactions that require detailed isomeric or individual analysis in order to differentiate between distinct reactivities observed under the same reaction conditions.

Structure and Spectroscopy

Section 1: Molecular Mechanics

Rationalising Selective Dimerisation and Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene

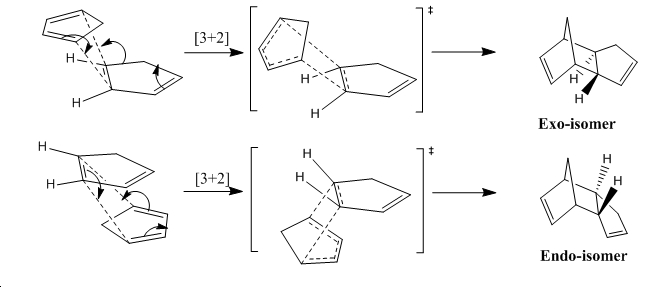

Cyclopentadiene dimerises in a concerted [3+2] cycloaddition mechanism due the ability of the cyclic system to act as an electron rich alkene, whilst also retaining electron poor diene character. The mechanism shown below for the process has two possible isomeric products, of which the endo selectivity dominates. In order to rationalise this selectivity it can be surmised that the origin of the selectivity is either in the thermodynamic or kinetic stability of the dimers (X and Y), which has been analysed below in figure 1 and table 1.

∆Figure 1 - Dimerisation mechanisms for Cyclopentadiene forming the endo (X) and exo (Y) isomers

|

Energy Component |

Exo-isomer [kCal/mol] |

Endo-isomer [kCal/mol] |

Difference (Endo-Exo) [kCal/mol] |

|

Stretching |

1.28 |

9.72 |

8.44 |

|

Bending |

20.59 |

111.69 |

91.10 |

|

Stretch-Bending |

-0.83 |

-4.57 |

-5.40 |

|

Torsion |

7.67 |

24.81 |

17.14 |

|

1,4-Van der Waals |

4.23 |

28.79 |

24.56 |

|

Non 1,4-Van der Waals |

-1.44 |

-1.24 |

0.20 |

|

Dipole-Dipole |

0.38 |

0.43 |

0.05 |

|

Total Energy |

31.88 |

169.64 |

137.76 |

∆Table 1 - Energy Comparison of the endo and exo dimers of cyclopentadiene via molecular mechanics

This corresponds to an overall energy difference of 137.76kJ/mol or 0.22Hartree, which clearly would show a massive preference to forming the exo isomer if the reaction was thermodynamically controlled. The knowledge that the endo isomer is the major product proves that the reaction is undoubtedly kinetically controlled due to stabilisation of the transition state of the endo dimerisation mechanism shown above. This can be attributed to favourable orbital overlap in the endo transition state as illustrated below in figure 2.

∆Figure 2 - Diagram of Stabilising factors promoting kinetic control of dimerisation

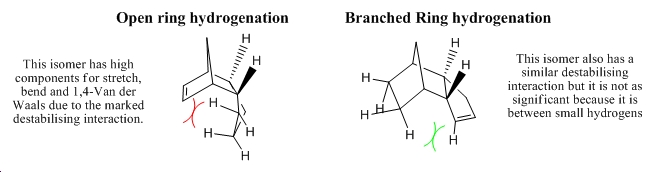

From this selective dimerisation a thermodynamic preference is observed in hydrogenation. A monohydrogenated product is obtained for short reaction times and one of the two possible isomers selectively dominates. On a basis of molecular mechanical analysis of the two possible isomeric products the selectively produced isomer can be found to be the 'open-ring' hydrogenation product. This is the kinetic hydrogenation product as can be observed from the molecular mechanics energy contributions featured in table 2, that clearly emphasises that the 'branched-ring' isomer is the thermodynamic product with an energy difference of 4.78k Cal/mol or 7.62x10-3 Hartree. The greater stability of the 'branched-ring' isomer can be attributed to the lesser effect of diaxial destabilising processes in the motions of stretching, bending, torsion and in terms of limited repulsive electronic Van der Waals contributions, which has been analysed illustratively in figure 3. These contributions make up the vast majority of the overall energy and factors stabilising these processes are therefore important. Table 2 shows the results of molecular mechanics treatment.

∆Figure 3 - Illustration of hydrogenation isomers named here 'branched ring hydrogenation' isomer and 'open ring hydrogenation' isomer

|

Energy Component |

Open Ring Hydrogenation-Isomer [kCal/mol] |

Branched Ring Hydrogenation-Isomer [kCal/mol] |

Difference (Open-Fused) [kCal/mol] |

|

Stretching |

1.22 |

1.10 |

0.12 |

|

Bending |

18.87 |

14.51 |

4.36 |

|

Stretch-Bending |

-0.76 |

-0.55 |

-0.21 |

|

Torsion |

12.25 |

12.50 |

-0.25 |

|

1,4-Van der Waals |

5.75 |

4.51 |

1.24 |

|

Non-1,4-Van der Waals |

-1.56 |

-1.05 |

-0.51 |

|

Dipole-Dipole |

0.16 |

0.14 |

0.02 |

|

Total Energy |

35.93 |

31.15 |

4.78 |

∆Table 2 - Energy Comparison of the fused ring and open ring hydrogenation products via molecular mechanics

As the more stable isomer has been judged to be favoured by the hydrogenation process and the knowledge that only after prolonged hydrogenation does the tetrahydrogenated dimer form, the hydrogenation mechanism is therefore thermodynamically controlled until all dimers have been hydrogenated on the 'branched alkene' in an exhaustive fashion.

The limitations of the molecular mechanics approach is obvious in this case as the energy contributions for products are shown to give no information about the possible isomeric transition states of the reaction and do not consider the origin of isomeric control. Also it does not take into account the electronics of the transition state. However, given the knowledge of the major product isomer, they have helped to reason whether the reaction must be thermodynamically or kinetically controlled. For the molecular mechanics values to be useful they must not both be coincident inside the error limit of the this purely classical approach for both isomers. As the energy difference between the hydrogenation isomers is 4.78kCal/mol or 7.62x10-3Hartree the reasoning can be said to reliable.

Rationalising Selectivity in Nucleophilic Addition to Optically Active NAD+ Analogues

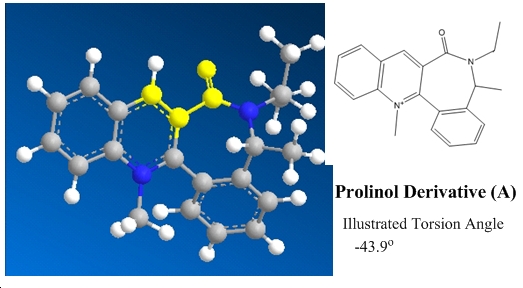

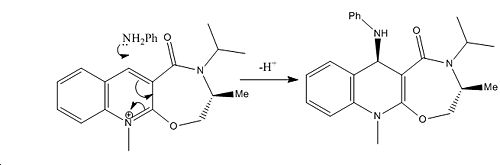

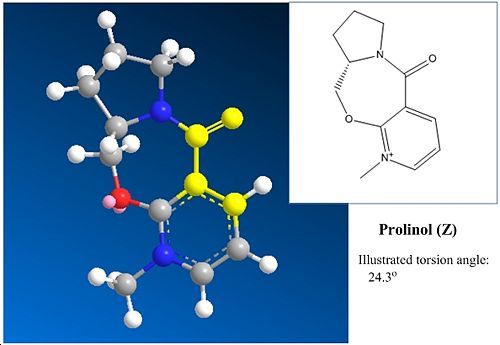

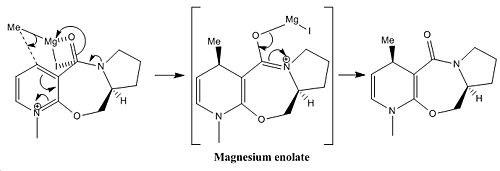

The reaction mechanisms of interest are shown below in figure 4, with the first showing prolinol reactant (Z) proceding to react with methyl magnesium iodide via a magnesium enolate intermediate[1] and the second an amine attacking a similar molecule (A). Included in the diagrams are some important highlighted angles and the ball and stick and skeletal structures of the relevant molecules.

∆Figure 4 - Mechanisms and identified structural characteristics for the considered reactions

In this example the most important aspect of the molecular mechanics approach is consideration of the absolute geometries of the reactants and the effect that has on the attacking species in nucleophilic reactions. This is in direct contrast to the energetic treatment of the products seen in the previous section. This illustrates another useful method for investigating stereochemical consequences of reaction mechanism. Although the breakdown of the specific energy contributions is not important in this case it is worth noting that the products will be higher in energy than the reactants due to loss of aromaticity in the pyridyl ring and therefore destabilised contributions from molecular motions such as stretching, bending, stretch-bending and torsion in particular.

In the reaction of prolinol Z, it can be seen that a torsion angle is made of 24.3o between the carbonyl and the attacked position on the pyridyl ring. In this case it can be stated that the resulting methyl orientation is optically dependant on torsion angle produced by the carbonyl in respect to the aromatic ring as it can be seen that due to the intermediate enolate formation the methyl will attack at the face directed onto by enolate formation. The larger the torsion angle observed the greater the directing ability and the more stereoselectivity will be yielded. Although the carbonyl is not attached this is an example of neighbouring group participation. It is notable that there are two enantiomers of the starting reagent Z and it can be said that given the alternate enantiomer as electrophilic species the product would be formed with the opposite methyl orientation due to the negatively related torsion angle of the carbonyl and the aromatic ring in the alternative enantiomer Z' with respect to that observed in Z. This concept is illustrated in figure 5.

∆Figure 5 - Analogous reaction of Z' with methyl magnesium iodide showing sterochemical consequences.

In the reaction of A with phenylamine a differing phenomenon is observed. In comparison of the reagents A and Z a quinoline analogue has been introduced to block attack at ortho and meta pyridyl positions in order to observe the stereochemical consequence of attack at the para position. This was unnecessary for Z as the carbonyl placement allows preferential directed attack of the para postion. As the nucleophilic amine contains a large phenyl group, which will hinder attack of sterically protected areas of A, it is expected that the face of attack would be the top face due to the torsion angle of -43.9o as illustrated to avoid destabilising electronic repulsions between the incoming amine and the carbonyl which are both electron rich species. Overall, this means that the topside of the molecule (as viewed on the page) is stereospecifically favoured. The higher the torsion angle of the carbonyl with respect to the aromatic ring, the greater the effect of directing the nucleophile onto the top side of the molecule. The prediction could be made that under increased reaction temperatures the selectivity of the reaction would be reduced due to the higher conformational flexibilty changing the angle of the carbonyl with respect to the aromatic ring via increased thermal agitation.

In the case of this exercise the classical molecular mechanics approach has been useful in rationalising the stereoselective mechanistic formation of the products with reference to the starting materials signifying the further utility of this approach. As reported in Allinger's original reporting of the MM2 force field molecular mechanics approach[2] this approach has limitations. The flaws that are significant for this example is notably the poor accountability for the effect of charge and aromaticity on the electronic distribution of the molecule. This effect is the most significant due to the use of the MM2 force field to describe the energetics and preferred geometries of charge bearing reactants, by a mostly steric component that dominates treatment of the preferred geometry and therefore overall energy. This example would therefore benefit from the inclusion of some degree of quantum mechanical treatment of the electronic distribution. It would be interesting to observe the effect on the energy and geometry output for a semi-empirical modelling scheme. The method chosen does however serve to explain the reaction phenomenon even if there is a degree of error in the absolute values for the carbonyl torsion angle with respect to the aromatic ring. Also treatment of the transition states would improve the approximation by spatially illustrating the preferred attack trajectory in which the true effect of angles could be probed.

Further flaws of molecular mechanics such as poor treatment of functional groups and 'unusual' chemistry do not factor significantly into the discrepancy compared to the real values, as functional groups do not participate in the reaction mechanism and addition to a ring to quench charge on an electronegative atom is a fairly intuitive and simple type of chemistry, which is modelled fairly well by this approach.

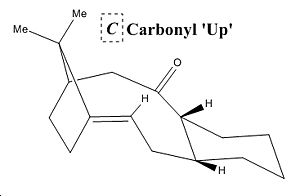

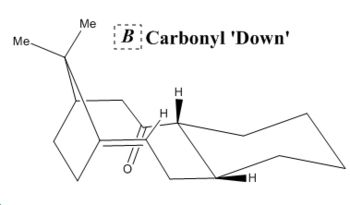

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

This analysis introduces the concept of atropisomerism. Atropisomers are structures with identical chemical composition that differ only in the conformations produced by the sterically hindered rotation of a single bond. This was formally defined by Oki that the isomers have an interconversion half-life of above 1000 seconds[3] at given temperatures. Taxol is a pharmaceutical drug and the intermediate atropisomers (B and C) depicted below are integral to it's total synthesis. Molecular mechanics was utilised to determine the most stable isomer, with results shown in figure 4 and table 4, whilst a primary objective was to explain the usually low reactivity of the alkenes present, especially upon functionalisation by substituting for hydrogen in B and C below.

|

Jmol Representations of the structures of the Isomers of Taxol |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

∆Figure 6 - Jmol Representations of the molecular isomers of intermediates in the synthesis of Taxol as resolved by molecular mechanics. Note: Erroneous non-inclusion of dimethyl on C structure. However DFT optimised file contains dimethyl however SCAN was run on erroneous isomer to get .XML file. Optimised file is linked here: [1]

∆Table 3 - Energy Comparison of the isomers of an intermediate in the total synthesis of Taxol via molecular mechanics

Stereochemistry of carbonyl addition is dependant on the most stable isomer which is formed in abundance prior to reaction. This atropisomer is C with the carbonyl facing 'down' in the opposite direction to the bridging carbon, which by visual representation appears a lot more natural structure. This isomer is produced in greater quantities and so therefore produces enantioselective carbonyl addition products in neutral pH conditions. The breakdown of energy contributions shown in table 3 shows that C is significantly more thermodynamically stable to the processes of stretching and bending which is indicative of it's more spatially efficient structure with a smaller energetic barrier to elongation and bending through the centre of the molecule as visualised in the table above. In B due to the unnatural conformation the cyclohexyl group is forced into a twist boat conformation which increases the destabilisation from 1,3-diaxial interactions, which are encapsulated in the 1,4-Van der Waals energy contribution.

Upon functionalisation, the alkene reacts slowly as it is now tetrasubstituted with alkyl groups and due to the fact that it has eliminated alpha to a bridgehead carbon which has a high enthalpic barrier to reverse, is termed a hyper-stable alkene. The 'Burgi-Dunertz' angle of sp2 attack is guarded by the large alkyl groups however the alkene is also eliminated alpha to a bridging carbon which adds further kinetic stability by terminating the desire to relieve steric strain. The alkene is electron neutral and non-polar and therefore reacts slowly and only under forced conditions.

The original hyperstable alkenes were reported on by Schleyer[4] in 1981 who used Allinger's MM1 force field to compute the energies of bridgehead olefins and in the process recognised hyperstable alkenes where one end of the alkene is a bridgehead carbon as well as di-alkyl substituted. The formation of these compounds are in direct contravening of Bredt's rule[5] which was formulated in 1924, which was reviewed by Fawcett[6] in 1950 building on work of the time suggesting that the bridgehead-eliminated olefin could be observed in bicycloalkenones over a certain critical size. The bicyclic system in the taxol intermediate illustrates this with a seven membered ring allowing the isolation of the bridgehead hyperstable olefin. As seen from the Jmol representations figure 6, the isolation of these ring systems is governed by the transannular distance which decreases as the ring size increases, destabilising the olefin. The utility of the molecular mechanics is increases further by it's ability to illustrate such effects despite a documented limitation of the approach being 'usual bonding'.

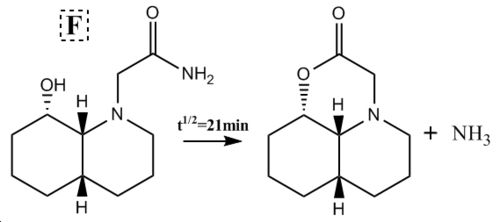

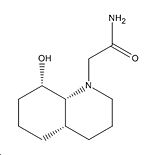

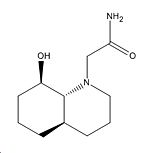

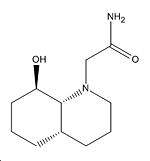

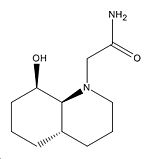

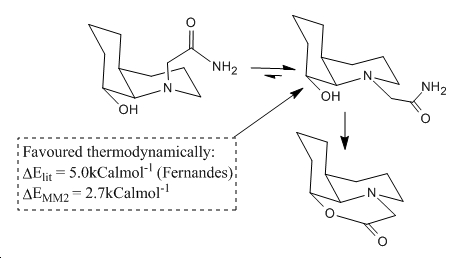

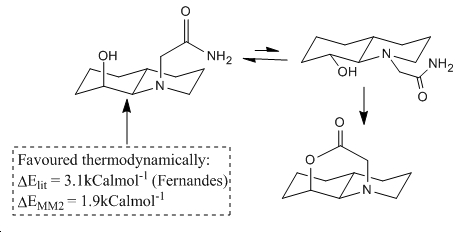

Peptide Hydrolysis at Room Temperature

In peptides room temperature hydrolysis is extremely slow at neutral pH due to NH2 being a worse leaving group than the attacking nucleophilic hydroxide and therefore the tetrahedral intermediate will collapse favouring the reformation of the amide bond. The oxygen lone pair used in hydrolysis will also be in a rapid dynamic equilibrium with protic species, rendering it less nucleophilic. Two isomeric forms of the reactant were studied for each of the two reaction schemes given and the stabilities for each were considered using molecular mechanics.

∆Figure 7 - Experimental halflives for room temperature hydrolysis of peptides F and G

∆Table 4 - Energy Comparison of the isomers of F and G via molecular mechanics

Burgi and Dunitz[7] originally reported on the high selective angular requirement for nucleophilic approach and short distance between nucleophile and electrophile is very important also in the intramolecular versions of the amide cleavage where the nucleophilic species is constrained by the geometry of the molecule. This explains why different reactivities are observed for isomeric reactants as the preferred conformations will place the nucleophilic oxygen and the intramolecular carbonyl at varying spatial distances apart and varying angles. This fully explains the difference in kinetics observed in the literature, however molecular mechanics can be utilised in order to analyse nucleophile-electrophile proximity and angular location. The angular dependance for attack of an sp2 centre is ~107o which was coined the 'Burgi-Dunertz angle'[8] and nucleophilic transition state trajectories that abide by this angle will show improved reactivity to amide cleavage when intramolecular neighbouring group participation is also incurred as in these intramolecular examples. Table 5 below shows the varying distance and angle between nucleophilic oxygen lone pair and electrophilic carbonyl carbon. It is also worth noting that in intramolecular annulations the formation of six-membered rings is a geometrically favourable process to form the morpholinoactone[9] product.

|

Property |

Isomer of F |

Isomer of G |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carbon-Oxygen Distance |

4.546Å |

3.325Å |

3.021Å |

3.040Å |

|

Dihedral Angle (O-C-O) |

107o |

108o |

65o |

61o |

∆Table 5 - Angular dependance and distance between nucleophilic oxygen and electrophilic carbonyl carbon.

From the results in the table above it can be seen that indeed the best match of the dihedral angle to the Burgi-Dunertz angle is the two F isomers in equal measure. The shortest distance between nucleophilic oxygen and electrophilic amide is for the thermodynamically preferred isomer of F. This is significant as the most abundant isomer of F in equilibrating conditions is the one that meets the optimal requirement for rapid nucleophilic attack is met and so rapid amide cleavage is observed. This process is treated in figure 8 which is adapted from the literature[10] to explain the short half life and comparisons of the thermodynamic energy difference reported and that calculated above in table 4 has been shown.

∆Figure 8 - Equilibrium picture of amide cleavage scheme featured in figure 5 for isomer F.

The isomers of G have been treated in an analogous way and it is notable that these isomeric forms are of much lower energy due to the much more planar array of the rings. Because of this the angles and distances considered in table 5 show poor accordance to those set out as optimal for sp2 nucleophilic attack. Of the two isomers of G the thermodynamic isomer is the one that is least amenable to nucleophilic attack and so in an equilibrating mixture of isomers only a small amount of thermodynamically unfavoured isomer is present at any time and therefore there is a much slower half life of reaction. This is considered in an analogous way to figure 8 in figure 9 below which is again adapted from the literature[11].

∆Figure 9 - Equilibrium picture of amide cleavage scheme featured in figure 5 for isomer G.

In comparison of the literature values obtained for the isomeric energy differences this emphasises the failings in the accuracy of the energy contributions obtained by the molecular mechanics approach. However the results do serve to point towards the reported results and do produce an accurate enough molecular geometry in order to explain the reaction phenomenon. The observation of the lower energy of the F isomer with the hydroxyl group equatorial is reportedly due to destabilising synaxial interactions in the axial-hydroxyl isomer[12]. As reported by Suggs and Pines[13] the attacking hydroxyl group is activated through hydrogen bonding to ring nitrogen lone pair which stabilises the transition state.

Section 2: Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Switching methodology to semi-empirical molecular orbital theory moves from a purely classical molecular mechanics approach to incorporating some quantum mechanical treatment in a so-called 'semi-empirical molecular orbital' treatment. The aim of this section is to illustrate the differences between the two possible approaches and the advantages and failings of each.

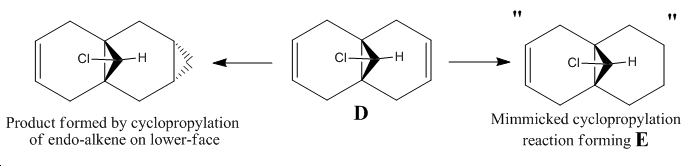

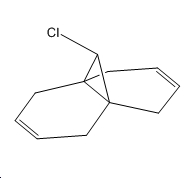

The reaction that is to be studied is the selective cyclopropylation of compound D using dichlorocarbene which is a reagent formed in-situ via irradiation of chloroform in the presence of D, where chloroform also acts as solvent medium for the reaction. The newly formed cyclopropyl ring sterically favours formation on the bottom face of the bicyclic system[14].

The cyclopropylation product will be modelled slightly differently from its real structure in the name of simplicity. D shows selectivity towards cyclopropylation of the alkene endo to the bridged chlorine atom as cited in the literature[15] (E). Both of D and E have been computationally analysed using molecular mechanics and semi-empirical molecular orbital approaches. Two types of semi-empirical methods have been used which are namely:

1)Hartree-Fock self-consistent-field molecular orbital treatment using the 'STO-3G' basis set which approximates the valence electron wavefunction concentrating primarily on the HOMO orbital which is presumed to participate majorly in the reaction.

2)Density Functional B3LYP molecular orbital treatment using the '6-31G(d)' basis set which is a more comprehensive computational method in which a better approximation is made to the electronic wavefunction.

∆Figure 10 - Mimmicked cyclopropylation of D showing product E for simplified modelling

Firstly, the geometries for each molecule D and E are considered, as optimised, by each of the three methods. As also stated in the literature an important characteristic to the selectivity observed is the geometry of the molecule which has been compared for each computational approach in measurement of the respective distances between the endo double bond and the bridging carbon and the same length for the exo double bond as predicted by each approach. This has been done below in table 5, from which it can be seen that the selected distances change very significantly between the molecular mechanics (MM2) approach and the Hartree-Fock (HF) semi-empirical approach and a slight adjusting of the HF distances acquired to obtain the DFT approximation which is considered to be the best. It can therefore be observed that the use of molecular mechanics to predict molecular geometry can be vastly improved upon by incorporating a semi-empirical approach and further improved (but to a lesser degree) by including further electronics in the DFT approach. This confirms the failings of the molecular mechanics model in particular, in the prediction of geometries and also the importance that quantum mechanical electronics has in the resultant real time-averaged geometry of a molecule.

The endo carbons can be seen to be approximately 0.20Å further away from the bridgehead carbon than the corresponding distance for the exo carbons. The reasoning for this will be treated by looking at the molecular orbital of the species in figure 11.

|

Jmol Representations of the structures of D, E, H and I Respectively |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

∆Table 6 - Jmol Representations of the molecules D, E, H and I as obtained from DFT molecular orbital theory.

|

Distance |

No Substituents |

Substituents |

||

|

D |

E |

H (-Nitrile) |

I (-Methoxy) |

|

|

Exo C=C-Bridge Carbon (MM2) |

3.22Å |

3.20Å |

3.20Å |

3.24Å |

|

Endo C=C-Bridge Carbon (MM2) |

2.97Å |

3.21Å (Average) |

2.98Å |

2.98Å |

|

Exo C=C-Bridge Carbon (HF) |

3.24Å |

3.21Å |

3.23Å |

3.23Å |

|

Endo C=C-Bridge Carbon (HF) |

3.02Å |

3.24Å (Average) |

3.02Å |

3.02Å |

|

Exo C=C-Bridge Carbon (DFT) |

3.28Å |

3.26Å |

3.30Å |

3.29Å (Average) |

|

Endo C=C-Bridge Carbon (DFT) |

3.03Å |

3.21Å (Average) |

3.03Å |

3.03Å |

∆Table 7 - Integral distances involved in the derivation of the selectivity of the reaction scheme shown.

Secondly, the energetics approximated by molecular mechanics have been considered in table 8 from which, it can be seen that as expected the overall effect of adding substituents to the exo-double bond has an associated energy debt. The difference in energy between H and I can't be attributed to the difference in electronic nature as molecular mechanics is dominated by steric factors and such a large energy distinction between the two molecules is attributable to the effect these groups have on the ease of molecular motion in terms of the subset energy contributions. For example the non-planar methoxy group destabilises I more than the planar nitrile group destabilised H with respect to D due to the greater capacity for the methoxy group to come into close proximity of the rest of molecule I in the processes of stretching, bending and stretch-bending.

|

Energy Contribution |

D [kCal/mol] |

E [kCal/mol] |

H [kCal/mol] |

I [kCal/mol] |

Energy Differences (E-D) |

|

Stretching |

0.61 |

0.89 |

0.69 |

1.19 |

0.27 |

|

Bending |

4.81 |

4.69 |

5.52 |

8.35 |

-0.12 |

|

Stretch-Bending |

0.04 |

0.01 |

-0.01 |

0.14 |

-0.03 |

|

Torsion |

7.62 |

10.79 |

7.06 |

11.04 |

3.17 |

|

1,4-Van der Waals |

5.79 |

6.97 |

6.10 |

11.01 |

1.18 |

|

Non-1,4-Van der Waals |

-1.08 |

-1.09 |

-1.66 |

-1.92 |

-0.01 |

|

Dipole-Dipole |

0.11 |

0.07 |

1.32 |

0.08 |

-0.04 |

|

Total Energy |

17.91 |

22.34 |

19.02 |

29.90 |

4.43 |

∆Table 8 - Energy Comparison of the D, E, H and I via molecular mechanics

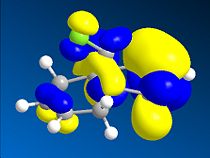

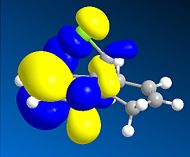

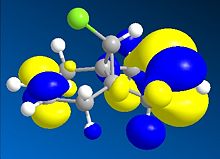

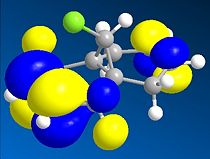

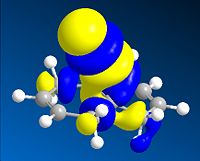

Thirdly, the molecular orbitals produced by the Hartree-Fock method are shown below and give good insight into the selectivities observed for this molecule. The LUMO+2 orbital can be seen to be the σ* C-Cl orbital, the HOMO the endo-π orbital and the HOMO-1 the exo-π orbital as reported in the literature[16]. The HF semi-empirical model is therefore very useful in producing molecular orbital forms that are highly distinguishable in terms of the assigning the major localisation and therefore reactivity of the molecule. The HOMO orbital is cited as[17], and is intuitively, the most reactive towards electrophilic attack of the carbene from which you would expect addition to the diene endo to the chlorine atom.

The intramolecular donation of electron density from the exo-π orbital into the C-Cl σ* orbital is attributable to the difference in distance from bridgehead carbon to each double bond (or corresponding bond in derivative) via this favourable stereoelectronic secondary molecular orbital effect. It is this interaction that is responsible for the regioselectivity observed as the donation of electron-density from the exo-π (HOMO-1) orbital to the σ* C-Cl (LUMO+2) orbital makes the exo-π orbital more electron poor that the endo alkene and less nucleophilic in terms of its likelihood of reacting with the electrophilic carbene, thus the selectivity is towards reaction with the endo-alkene. This process is therefore an example of neighbouring group participation as a secondary orbital effect or stereoelectronic effect assists the observed selectivity.

|

Stills of the Molecular Orbitals of D  |

||||

|

HOMO-1 |

HOMO |

LUMO |

LUMO+1 |

LUMO+2 |

|

|

|

|

|

∆Figure 11 - Molecular Orbitals produced by Hartree-Fock Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

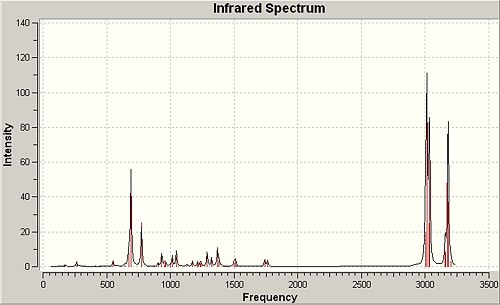

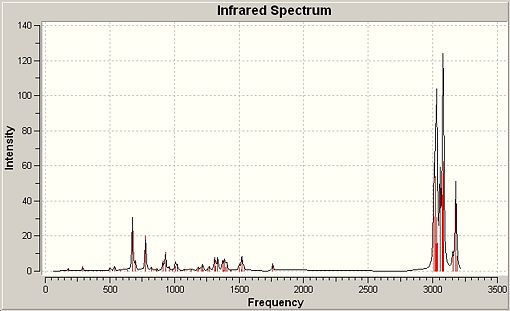

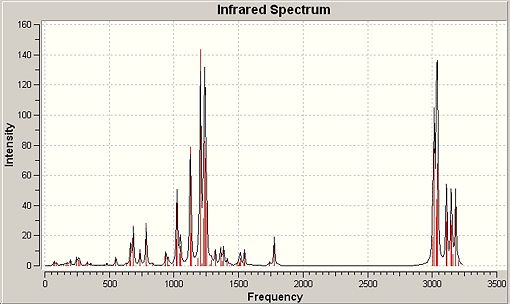

The infrared stretching frequencies, as predicted by the density functional B3LYP molecular orbital treatment, were investigated for compounds D and E in order to identify the spectroscopic differences between the two molecules. Only stretching frequencies of interest have been included in the analysis. The scanning process was speeded up for the diene D by assigning the molecule Cs point group symmetry. However the same process could not be done for the monohydrogenated E as it does not have Cs symmetry.

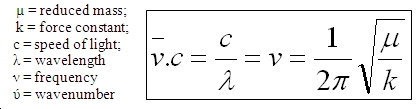

∆Table 9 - Infrared Spectrum of D and E with peak annotations

The equation governing the frequencies observed is shown below. According to the stereoelectronic effect mentioned earlier and using the equation shown below the expected result is obtained. The electron density donated to the σ* LUMO+2 orbital from the exo-C=C localised π HOMO-1 orbital removes bonding electrons reducing the bond order and therefore lowering the strength of the bond. As can be seen from the equation below a weaker bond corresponds to a lower force constant k and therefore an increase in the vibration wavenumber. As the monohydrated alkene E does not have this same stereoelectronic effect the wavenumber of the exo C=C bond vibration is expected to be higher in D than that in E.

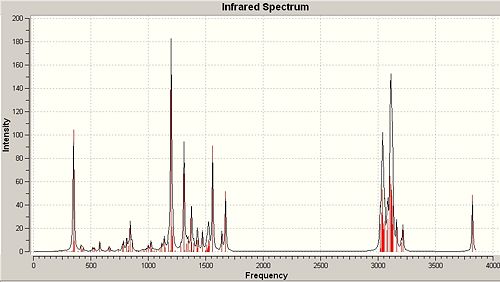

Finally, the ability of the density functional B3LYP molecular orbital treatment to incorporate substituent electronic nature into this analysis has been analysed below through the use of compounds H and I. These compounds include substitution of the exo double bond with extremes of electron withdrawing and electron donating substituents utilising nitrile and methoxy groups respectively to exemplify this whilst keeping the overall molecular complexity low.

∆Table 10 - Infrared Spectrum of H and I with peak annotations

As can be seen from the above data it is clear that altering the electronic nature of the substituents on the exo double bond does have the effect of changing the stretching frequencies of the double bonds. It would be expected that in the case of adding the electron withdrawing substituent nitrile groups to the exo double bond this would have the effect of reducing bond order and reducing the wavenumber of the vibration by reducing the force constant k which is directly related to the strength of the bond. In the converse situation it would be expected that the electron donating methoxy substituent would increase the bond order increasing the strength of the bond and the force constant k, increasing the wavenumber of the vibrations of interest. This effect is seen for the exo double bond but the effect on the electronic nature of the extended molecular is not observed. A strange effect is observed for the wavenumber of the carbon-chlorine bond vibration which saw the vibration increased in the case of both extremes of substituent electronic nature when it may be expected that opposing effects would be observed for opposite electronic nature. This shows the limitations of using only semi-electronic approaches and the overall importance of including maximum amounts of electronic consideration, without making the calculation impractical or even impossible with current techniques, for prediction of spectroscopic properties.

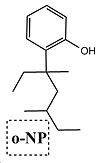

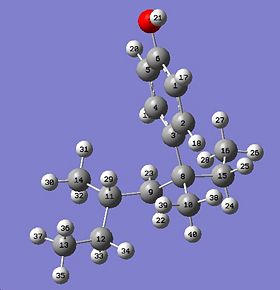

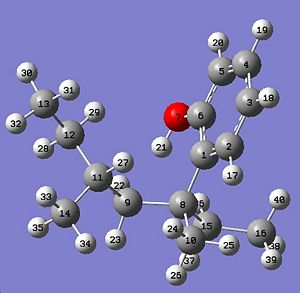

Section 3: Mini-Project - Nonylphenol Isomeric Products

Introduction

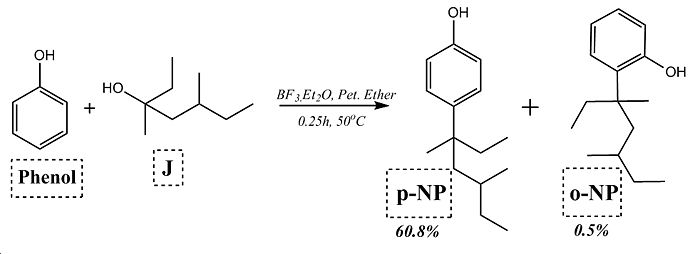

The reaction being studied by this method is the Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of carbolic acid (phenol) using a tertiary nonylalcohol and Boron Fluoride catalyst. The reaction conditions for formation of the isomeric product are shown below in figure 12. Anaylsis of the isomers of nonylphenol are cited in the following literature for analysis by mass spectroscopy producing characteristic signals with minimal noise interference with high signal to noise ratio[18][19][20], however unfortunately this method could not be used to differentiate between the isomers produced by the reaction below and does not lend itself well to computational prediction. The best method for differentiating between the isomers would be to use H and C NMR spectroscopy with the isomers differing in the coupling observed for the aromatic phenol hydrogens/carbons. As NMR spectroscopy is the best method for resolving these isomeric products, it adds further interest to the question "is the GIAO method a good means of predicting the 13C NMR spectrum of a set of isomers".

∆Figure 12 - Reaction scheme for cited reaction for study by GIAO method.

Clearly the reaction mechanism above shows selectivity to the para-alkylated isomer and this will be investigated by means of the methods used earlier in this report. It is important to note that other side products are produced by this mechanism such as the dialkylated product but since this is not isomeric in respect to the major product of the reaction this has not been considered despite having a 2.5% yield. A range of nonylalcohol reagent isomers could have been considered, however these were not chosen as the degree of alkyl branching was lesser and a known limitation of this computational approach is for molecules that show high conformational flexibility.

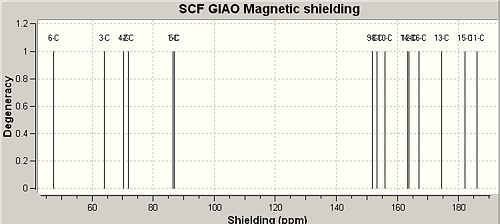

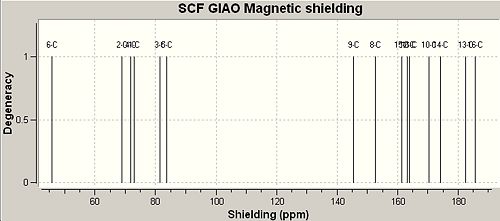

Predicting the 13C NMR Spectrum of Nonylphenol Isomeric Products using the GIAO Method

NMR files were unable to be published to D-space as an error message was received, so Gaussian log files were uploaded and linked here - p-NP[2]o-NP[3]

|

NMR Spectra for the molecules p-NP and o-NP |

|||||||

|

Major Product p-NP |

Minor Product o-NP |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Chemical Shift |

Predicted 3JH-H |

Atom Assignment |

Literature Shift[21] |

Chemical Shift |

Predicted 3JH-H |

Atom Assignment |

|

|

86ppm |

3JH17-H18 = 8.2Hz |

C1 |

114.5ppm |

73ppm |

N/A |

C1 |

127.2ppm |

|

72ppm |

3JH18-H17 = 8.2Hz |

C2 |

127.7ppm |

69ppm |

3JH17-H18 = 8.2Hz |

C2 |

127.8ppm |

|

64ppm |

N/A |

C3 |

140.0ppm |

81ppm |

3JH18-H17 = 8.2Hz |

C3 |

132.2ppm |

|

70ppm |

3JH19-H20 = 8.2Hz |

C4 |

127.7ppm |

72ppm |

3JH19-H20 = 8.2Hz |

C4 |

127.3ppm |

|

87ppm |

3JH20-H19 = 8.2Hz |

C5 |

114.5ppm |

84ppm |

3JH20-H19 = 8.2Hz |

C5 |

142.2ppm |

|

47ppm |

N/A |

C6 |

152.6ppm |

46ppm |

3JH19-H20 = 8.2Hz |

C6 |

153.1ppm |

|

153ppm |

N/A |

C8 |

40.6ppm |

153ppm |

N/A |

C8 |

32.5ppm |

|

87ppm |

3JH23-H29 = 2.1Hz |

C9 |

50.7ppm |

84ppm |

3JH22-H27 = 5.0Hz |

C9 |

44.9ppm |

|

167ppm |

N/A |

C10 |

22.9ppm |

170ppm |

N/A |

C10 |

19.7ppm |

|

164ppm |

3JH29-H23 = 2.1Hz |

C11 |

30.5ppm |

164ppm |

3JH27-H22 = 5.0Hz |

C11 |

32.6ppm |

|

163ppm |

3JH33-H36 = 13.9Hz |

C12 |

31.3ppm |

163ppm |

3JH28-H27 = 12.3Hz |

C12 |

31.4ppm |

|

182ppm |

3JH36-H33 = 13.9Hz |

C13 |

11.2ppm |

182ppm |

3JH30-H28 = 2.7Hz |

C13 |

12.0ppm |

|

175ppm |

3JH30-H29 = 2.9Hz |

C14 |

21.2ppm |

174ppm |

3JH33-H27 = 2.6Hz |

C14 |

20.7ppm |

|

156ppm |

3JH25-H27 = 2.8Hz |

C15 |

36.0ppm |

161ppm |

3JH37-H38 = 2.6Hz |

C15 |

30.2ppm |

|

186ppm |

3JH27-H25 = 2.8Hz |

C16 |

8.5ppm |

186ppm |

3JH38-H37 = 2.6Hz |

C16 |

12.0ppm |

∆Table 11 - NMR Spectrum of p-NP and o-NP with peak assignments

The poor ability of the GIAO method to incorporate heavy atoms and complex electronic effects such as aromaticity is exemplified by table 10 above. The result of these limitations is that the shielding of aromatics and alkyl carbon's respectively has been inverted to give results that show the opposite trends to the literature shifts. The literature shifts were obtained from the cited places and due to not being able to find literature 13 NMR shifts for o-NP the shifts were predicted by considering the products of fragmentation.

According to the literature shifts adjustments would need to be made to carbon's directly attached to heavy atoms, therefore C6 attached to 'heavy atom' oxygen was expected to have a shift error of approximately -3ppm[24]. However, the difference between the literature shifts and the experimental shifts was approximately 90ppm. The results files were saved as .mol files using ChemBio3d and input into Jannochio to attempt to predict 3JH-H coupling constants which are seen to give very reasonable coupling constants that are clearly torsion angle dependant according to the Karplus equation[25] with the best coupling (largest constant) observed for three bond orientations with an antiperiplanar 180o arrangement. Of course the coupling constants predicted are averaged in many cases due to the rotation of sigma-bonds on the NMR timescale. The net result of this is that the largest and smallest shifts are not observed. The mid-range constants agreed well with the literature[26] although tabulated comparisons have not been made here.

In summary of this section the NMR approximation was proven to not be accurate for the chosen case and therefore no significant useful information can be extracted to enable acclaim for the computational method in prediction of real NMR spectroscopy, as 1H NMR is also notoriously poor in computation prediction. This method could not be used reliably in research application for such molecules as nonylphenol which have changable electronic distribution and relatively high conformational flexibility.

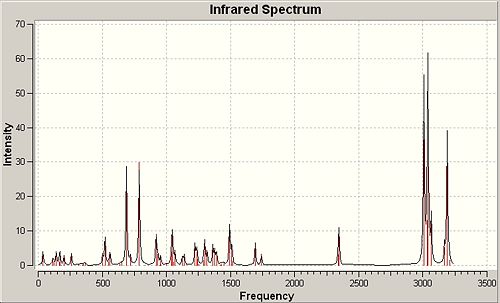

Vibrational Analysis

IR files were unable to be published to D-space as an error message was received, so Gaussian log files were uploaded and linked here - p-NP[4]o-NP[5]

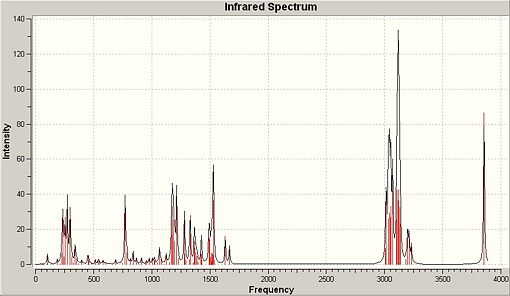

A method that has been shown to show reliable predictions to real spectroscopy for the chosen molecule is vibrational analysis. Table 11 shows the form of the IR spectra obtained via computational methods with some notable differences between the two isomers which accord nicely with expected rationale and literature citation[27]. Only some predicted vibrations that enable distinction between the two molecules have been included.

∆Table 12 - Infrared Spectrum of p-NP and o-NP with significant peak annotations

There are stark differences between the forms of the IR spectrum of p-NP and o-NP. As the two molecules are regioisomers the number and form of each individual vibration should be very similar, however just by looking at the predicted IR spectra of the two molecules it can be seen that several peaks vary in intensity. Some of these peaks include localised vibration of the OH bond in a ‘wagging’ fashion and such peaks are present at approximately 300-400cm-1 and 1100cm-1. These major peaks are included in the vibrational analysis table below. The rationale for these differences in vibration is derived in the placement of the phenolic hydroxyl with respect to its proximity to the vast alkyl system. For p-NP it can be seen that the O-H bond is at polar ends of the phenyl ring with respect to substitution of the nonyl alkyl chain which allows freedom of vibration. This freedom corresponds to a high intensity peak of that is clearly seen on the spectrum. Conversely, when treating the o-NP product the OH bond is close to the substituted branched-nonyl which has high intrinsic flexibility. Due to this flexibility the branched-nonyl alkane chain will interfere with the otherwise strong intensity vibration which makes it appear at much lower intensity which is not so clearly observed on the spectrum.

- p-NP - Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies = -660.999Hartree

- o-NP - Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies = -660.997Hartree

These values in the output file for each optimised geometry show the two isomers are extremely close in energy when optimised via DFT MO theory. The 0.002Hartree difference corresponds to a stability of p-NP over o-NP energy difference of only 1.25kCal/mol which is coindicent inside the method's error limit, showing just how close the two are in terms of Gibbs Free Energy.

Optical Rotation Analysis

OR files could not be uploaded to D-space as an error message was received, so the Gaussian log file was saved in .txt format and uploaded here - p-NP[6]o-NP[7]

The quaternary chiral centre was held constant for both molecules whilst the tertiary chiral centre was varied, with o-NP and p-NP having opposite optical configuration [see table 10 for confirmation] so the overall magnitude of the rotation observed would originate from one chiral centre. The rotations are weak which is referenced as being inaccurate when computed[28], but this process may provide valued information on the accuracy of weak optical rotations when two chiral centres are present in a molecule and one is held constant.

The predicted result is that the same modulus value would be obtained with the rotary degrees varying in sign. This method proves the poor accuracy of the values obtained with a discrepancy of approximately 78% in the modulus values. However, one useful aspect of the analysis is that the opposite sign of rotation is observed which adds some credibility to an otherwise poor approximation. This result is not unexpected as the degree of accuracy is highly dependant on conformation and as can be seen from the optimised geometries the most stable conformation for each isomer is different which can have a large effect on the computed optical rotation[29]. The conformation of the molecule that was originally input into the DFT calculations for better optimisation was that optimised via molecular mechanics. Five conformational structures were tried for each of the isomers in order to achieve close to the lowest possible energy possible via simple molecular mechanics. The results of this preliminary optimisation can be seen in the following section. The optical rotation values achieved are given below.

- o-NP Rotation: [α]D = 5.72o

- p-NP Rotation: [α]D = -25.90o

The origins of such errors in the absolute values are discussed in the literature[30] and the most significant in this case is likely to be conformational ambiguity, which is often a major problem to the GIAO method.

Molecular Mechanics of p-NP and o-NP

As mentioned earlier, prior to DFT optimisation the structures of o-NP and p-NP were optimised using molecular mechanics. The energy breakdown for the lowest energy conformation attainable via molecular mechanics has been featured below in table 12.

∆Table 13 - Energy Comparison of the isomers of Nonylphenol

As can be seen there is very little difference between the overall energy values obtained for each optimal conformation, when intuitively it would be expected that p-NP would be more stable in terms of the stretch, bend and stretch bending molecular energy contributions which is indeed the case. However, the close proximity of the overall energies can be explained by considering the energy stabilisation obtained via the ability of the oxygen lone pair to coordinate to H27. in a hydrogen bonding fashion to constrain and stabilise the shown conformation for o-NP, making it the most stable conformation by molecular mechanics means by over 3kCal/mol. Account for this hydrogen bonding stabilisation in molecular mechanics terms is in the much lower torsion energy for o-NP.

This method can't be used to rational the cited selectivity towards the phenolic para position as the results obtained point towards the reaction not being controlled thermodynamically, in which case an approximately 1:1 mixture would be expected. Of course the rationale for the selectivity lies in the combination of mesomeric effects and inductive effect's from oxygen making the para position more susceptible to electrophilic attack and proceeding to the product via Friedel-Crafts (SEAr) alkylation.

Conclusions

Through the course of this investigation it has been proven that, although molecular mechanics can give useful inside into the energetics of a set of molecules, electronic computational methods must be included to gain any significant degree of accuracy. Despite this the overall computational process has been shown to have many limitations and caveates that limit its use for complex molecules, which culminated in the results of the mini project.

Overall the computation methods were shown to have significant limitations for the molecules o-NP and p-NP. There were significant successes however, and it was shown that in this case infrared analysis was the most applicable method to computationally produce results that would allow discrimination between the two products. Given a typical reaction, under the conditions stated in figure....., it could be proven that a mixture of both isomers was produced by means of peak analysis of the 'bending' OH peaks observed at various key areas of the spectrum on the basis of intensity and absolute peak wavenumber.

As mentioned previously the rationale for the complex Friedel-Crafts SEAr was independent of the results obtained by molecular mechanics, however this section did suggest that the mechanism was not thermodynamically controlled. The major problem with Friedel-Crafts alkylation is overalkylation because the product is more nucleophilic than the starting material which is why the dialkylated o-p-NP was a major side product in the reaction.

The most disappointing aspect of the procedure was the extremely poor prediction of the 13C NMR spectrum, although the likely reasons for its failings have been well referenced. Further work should seek to fragment o-NP and p-NP molecules into phenol and nonylphenol derivatives and repeat the GIAO approach to observe the accuracy of the predicted 13C NMR shifts for these derivative molecules. If this experiment was a success it would imply that the cause of the problem was the inclusion of two very different types of electronic consideration in one molecule, being aromaticity and highly branched alkane chains. It is possible that this could lead to improvement of the computational method in terms of the computational combination of these two types of electronic distribution. However a possible adverse effect of this proposed plan is the higher conformational flexibility that would be afforded to the nonyl alkyl chain derivative that may further increase conformational ambiguity, which is known to be a major cause of inaccurate NMR prediction.

In certain specific situations computer modelling has very useful applications to modern chemistry and no doubt will be improved upon further in the future and will become a powerful influence in the methods of modern analytical and synthetic chemistry. It is however important to be fully aware of the range of limitations of theses featured approach so that the maximum amount of useful and more importantly reliable data can be abstracted.

References

- ↑ S. Leleu, C. Papamicael, Tetrahedron Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919

- ↑ N. L. Allinger, J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 99, 1977, 8127

- ↑ M. Oki, Topics in Stereochemistry, 1983, 1

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. V. R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 103, 1981, 1891

- ↑ J. Bredt, H. Thouet, J. Schmitz, J. Liebigs Ann. Chem., 1, 1924, 437

- ↑ F. S. Fawcett, Chem. Rev., 47, 1950, 219.

- ↑ H. B. Bürgi, J. D. Dunitz, Tetrahedron, 30,1974, 1563.

- ↑ H. B. Bürgi, J. D. Dunitz, Tetrahedron, 30,1974, 1563.

- ↑ J. W. Suggs, R. M. Pires, Tetrahedron Lett., 38, 1997, 2227

- ↑ N. M. Fernandes, F. Fache, M. Rosen, J. Org. Chem., 73, 2008, 6413

- ↑ N. M. Fernandes, F. Fache, M. Rosen, J. Org. Chem., 73, 2008, 6413

- ↑ N. M. Fernandes, F. Fache, M. Rosen, J. Org. Chem., 73, 2008, 6413

- ↑ J. W. Suggs, R. M. Pires, Tetrahedron Lett., 38, 1997, 2227

- ↑ H. S. Rzepa, R. Baoseb, B. Halton, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans., 1992, 447.

- ↑ H. S. Rzepa, R. Baoseb, B. Halton, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans., 1992, 447.

- ↑ H. S. Rzepa, R. Baoseb, B. Halton, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans., 1992, 447.

- ↑ www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Mod:Organic

- ↑ M. Moedera, C. Martin, J. Harynuk, J. Chromatography A, 1102, 2006, 245

- ↑ R Vinken, B. Schmidt, A. Schaffer, J. Label Comp. Radiopharm., 45, 2002, 1253.

- ↑ B. Thiele, V. Heinke, E. Kleist, J. Environ. Sci. Technol., 38, 2004, 3405

- ↑ R Vinken, B. Schmidt, A. Schaffer, J. Label Comp. Radiopharm., 45, 2002, 1253.

- ↑ T. Kinoshita, K. Shibayama, Chem. Soc. Jap., 61, 1988, 2917.

- ↑ P. LachanceCan. J. Chem., 57, 1979, 367

- ↑ www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Mod:Organic

- ↑ M. Karplus, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 85, 1963, 2870

- ↑ B. Thiele, V. Heinke, Environmental Science & Technology, 38, 2004; 3405

- ↑ R. Vinken, B. Schmidt, A. Schaffer, J. Label Comp. Radiopharm., 45, 2002, 1253.

- ↑ www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Mod:Organic

- ↑ www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Mod:Organic

- ↑ C.Rosini, B. Menucci, J. Org. Chem., 72, 2007, 6680