Rep:Mod:go114

Introduction

This experiment strives to model the behaviour of crystalline magnesium oxide at varying temperatures in terms of its Helmholtz free energy and the volume of a unit cell and to determine its thermal expansion coefficient. Two different methods are compared: the quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics calculations. The quasi-harmonic approximation is based on the fact that Lennard-Jones potential can be approximated as a parabola at energies around the equilibrium energy. This calculation is augmented by using the transformation of the crystal to k-space, where the phonons of the crystal are determined and added to the harmonic potential. These calculations are time-independent and carried out for a conventional or primitive unit cell. The molecular dynamics approach works by assigning velocities to ions in the crystal and solving the Shrodinger's equation according to the new positions and velocities of the ions at intervals of 1 fs, and uses a supercell (8 conventional cells stacked in a 2×2×2 pattern). The software used for the calculations is GULP and Crystal for the quasi-harmonic and molecular dynamics calculations respectively, both run on the DLVisualize platform.

Results and Discussion

Phonon dispersion and density of states

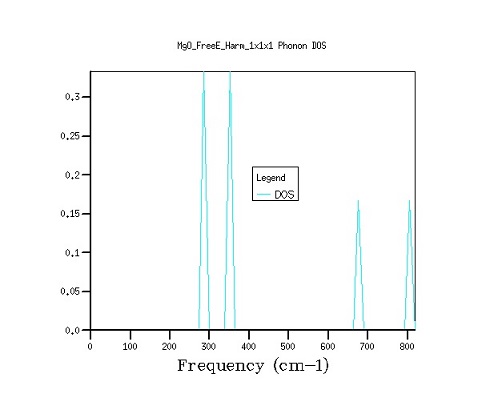

Figure 1. Phonon dispersion and density of state curves with a 1×1×1 grid.

The 1×1×1 grid seen in Figure 1 is computed for one of the symmetry points in the k-space, namely, point L, as evidenced by the fact that the frequencies match those of the point L of the dispersion curves. Furthermore, it can be observed that the density of states at the frequencies of 286 cm-1 and 351 cm-1 are twice those at 676 cm-1 and 806 cm-1, which matches the fact that on the phonon dispersion curve the former values have two degenerate bands each as opposed to only one for the latter two frequencies.

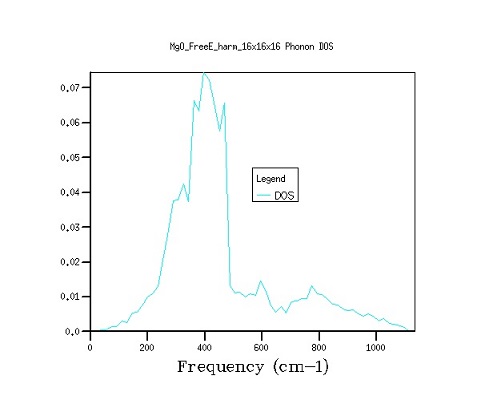

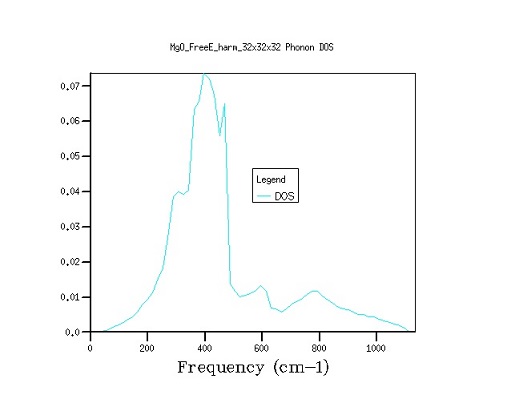

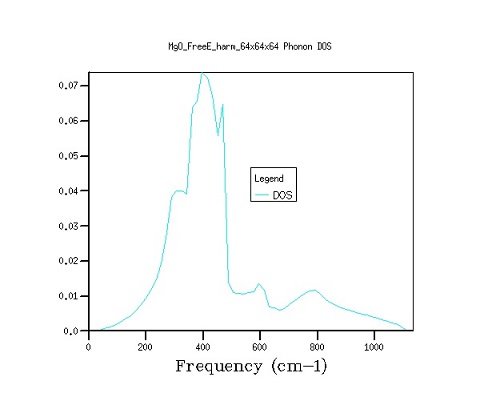

As the grid size increases, the relevant calculations are performed on more k-points and therefore the output better represents the reality predicted by the dispersion curves. As the phonon dispersion curve is a collection of uncountably many k-points, it is expected that the use of more k-points (larger grid) will provide density of state curves that match the phonon dispersion curves more closely, which is exactly what was observed by conducting further calculations. For example, when examining the phonon dispersion curve it can be seen that many bands cross the frequency of around 400 cm-1, meaning that many vibrations are degenerate at this frequency, and this is mirrored in the density of state curve, which shows a large peak at this frequency (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The comparison between density of state curves as grid size is varied from 16×16×16 to 32×32×32 to 64×64×64. As shown by graphs above (Figure 3), the transition from a 16×16×16 to a 32×32×32 grid gives a noticeably smoother distribution graph, while the transition to 64×64×64 grid only slightly changes the fine structure of the graph. This increase in accuracy, however, comes at the cost of calculating 8 times as many k-points, and therefore a vastly longer computation time, therefore 32×32×32 is the optimum grid size for the calculation. A decrease in the grid size will result in the loss of structure in the density of state curves, while increase of the grid size will bring an exponential growth in the computation time and only marginal improvements in the finer structure of the graph.

The optimum grid size is dependent on the material that is used. Similar materials such as calcium oxide would have a similar optimum grid size because of the similarities in charge (and therefore band energy) distribution as well as the roughly comparable size. In contrast, in metals the electronic structure can be approximated as "cation in the sea of electrons", where electrons move freely to counteract the movement of metal ions, therefore the vibrations would occur over a smaller range of energies, thus fewer k-points would have to be sampled for comparable precision and the optimum grid size would shrink. In a different vein, if a zeolite is used, a smaller grid would also be necessary, as a*=2π/a, and its structure is much larger and more complex than that of magnesium oxide, therefore the lattice parameter in the reciprocal space is much smaller and therefore less k-points are necessary for a similar level of accuracy.

Quasi-harmonic aproximation

Effect of grid size

| Grid size | A /ev | ΔA /mEV |

|---|---|---|

| 1x1x1 | -40.93030 | 3.82 |

| 2x2x2 | -40.92661 | 0.13 |

| 4x4x4 | -40.92645 | 0.03 |

| 8x8x8 | -40.92648 | 0.00 |

| 16x16x16 | -40.92648 | 0.00 |

| 32x32x32 | -40.92648 | 0.00 |

| 64x64x64 | -40.92648 | 0.00 |

Table 1. Helmholtz free energy as a function of grid size with precision calculations shown.

Examining Table 1, it can be seen that as grid size increases, the free energy is calculated for more k-points, iimproving the accuracy of the measurement to approach the value given by the quasi-harmonic approximation (though not necessarily the empirical value).

In this table the energy difference is calcuated between each point and the most precise point, in this case, that calculated with the 64×64×64 grid. After reaching a 2×2×2 grid the energy remains stable to 0.5 meV, while the 4×4×4 grid is accurate to 0.1 meV.

Effect of temperature

Figure 3. Lattice parameter and primitive unit cell volume as a function of temperature.

Expectedly, as temperature increases, so do the lattice parameter and therefore the volume of the primitive unit cell, as both of these quantities are related (Figure 3). This is entirely expected from empirical observations, i.e., substances expand while heated. In both cases the temperature range up to around 400 K shows a somewhat parabolic relationship, while after that the relationship has a more linear character. This can potentially be explained by the fact that phonons are the source of the anharmonicity in the graph and only at higher temperatures when there are more thermally populated bands does the effect become significant enough to outcompete the natural parabolic shape of the graph.

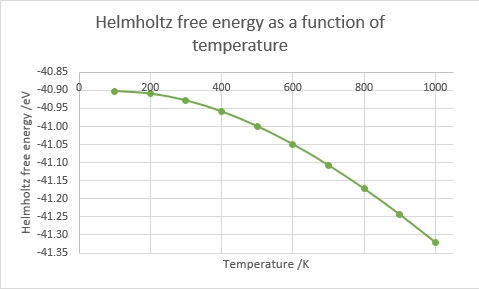

Figure 4.Helmholtz free energy as a function of temperature.

As temperature increases, Helmholtz fee energy decreases, i.e., becomes more negative (Figure 4). As free energy measures the energy that can be extracted from a system, it is no surprise that increasing temperature increases the amount of work that can be done by the system even after accounting for the losses as entropy, as the heat energy is stored within the crystal. Notably, there is no free energy at 0 K, but this is due to the fact that the system must be in its zero-point energy state and any molecular motion ceases, therefore no useful work can be extracted from the system.

Thermal expansion coefficient

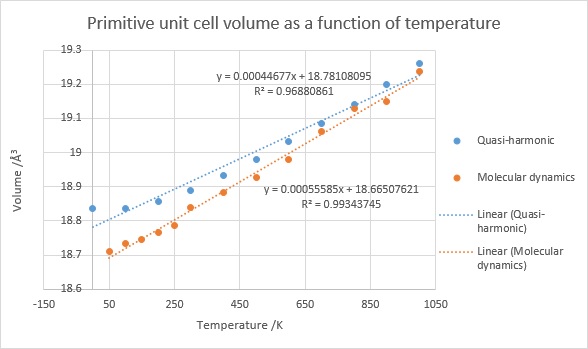

From the curves above the thermal expansion coefficient can be calculated, it is α=1/V×k =2.56×10-5 K-1 at 300 K ,where V is the volume of a unit cell at the desired temperature and k is the gradient of the V with respect to T curve (shown together with molecular dynamics analysis in Figure 5). In comparison, the literature value is 3.12×10-5 K-1,1 indicating that quasi-harmonic approximation underestimates the real value by 17.9%, which is rather substantial. To investigate where this error comes from, we can compare the density predicted by the quasi-harmonic approximation to the density of magnesium oxide in real life. The calculation leads to the value of ρ=M/(NA×V)=3.54 g cm-1 at 300 K, while the actual value at 300 K is 3.59 g cm-1,1 which means that the density approximation is within a margin of error of 1.4% from the real value. This indicates that even though the density at around 300 K is approximated well, the error in thermal expansion coefficient stems from either overestimation of density at low temperatures or its underestimation at high temperatures. Both are likely, as the assumption that the potential surface can be modeled by a parabola becomes less valid further from the equilibrium value (at high temperatures), and also molecular dynamics analysis shows no parabolic shape in the graph at low temperatures (Figure 5).

Another problem facing the accuracy of the approximation at high near-melting temperatures is that the anharmonicity introduced by phonons could distort the crystal structure enough to temporarily break the periodic nature of the crystals, meaning that one of the fundamental assumptions - periodicity - would not be true anymore.

As in reality from the Lennard-Jones potential curve it can be seen the increase in energy is steeper with bond length decreasing rather than increasing from the equilibrium value, at an energy higher than the zero-point energy of a system the extremes of a vibration are more skewed towards longer bond lengths. When averaged over many vibrations and atoms, it leads to an increase in the average bond length and therefore the overall expansion of the system. This is an effect that is ignored by the quasi-harmonic approximation, meaning that a diatomic molecule would still be predicted the same average bond length regardless of temperature. However, as crystals have a periodic 3D structure and their phonons can be calculated, they can be used to introduce some degree of anharmonicity in the approximation (hence, quasi-harmonic approximation), which allows to correctly predict that increase in volume will occur.

Comparison of quasi-harmonic approximation to molecular dynamics simulations

Figure 5. Volume of a primitive unit cell as a function of temperature obtained by quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics calculations.

Both methods provide roughly similar thermal expansion values, especially at higher temperatures, though the thermal expansion coefficient predicted by the molecular dynamics approach is 15% higher than that obtained from the quasi-harmonic approach at 2.95×10-5 (only 5.4% smaller than the literature value). From this it can be seen that the molecular dynamics approach is more accurate than the quasi-harmonic approximation.

Furthermore, if R2 values are examined, it can be seen that the thermal expansion predicted by the quasi-harmonic approach is better described by a parabola rather than a line, while that predicted by molecular dynamics is linear. This is due to the fact that quasi-harmonic approach uses a parabola to approximate the shape of the potential curve close to the equilibrium bond distance. As can be seen from Figure 5, the molecular dynamics approach matches a linear fit more closely, but can include more "noise"; the precision is reduced. This could be rectified by increasing the time of the simulation, as even if by the end of the simulation the vibrations centered around the average volume more than in the beginning, the differences were large enough to affect the running average value quite significantly. If run for longer than 500 femtoseconds used in this calcuation, the average calculated volume of the unit cell would become more accurate and therefore a smaller discrepancy from the line of best fit would be expected.

Due to the higher temperature-dependence of the cell volume predicted by the molecular dynamics approach, it is expected that higher temperatures would see more extreme vibrations than predicted by the quasi-harmonic approach, especially because the quasi-harmonic approximation is best at values close to the equilibrium. Furthermore, the real shape of the potential energy surface allows for bonds to be broken, which is not included in the quasi-harmonic approximation, therefore we would expect only the molecular dynamics calculation to show the melting of magnesium oxide. As upon melting magnesium oxide would lose its crystal structure, periodicity would be removed and therefore any calculation using k-space would break down as well. In contrast, the molecular dynamics approach, which is based on Schrodinger's equation, will provide a better model for this situation.

Conclusions

It was determined that 32×32×32 grid size was optimal for conducting calculations that use quasi-harmonic approximation. It proved to be a very powerful tool for quantifying the vibrations occurring in a magnesium oxide crystal, calculating the Helmholtz free energy and helping imagine bands in k-space. It could also be successfully used to determine the density of a magnesium oxide crystal at normal temperature. The drawbacks for using the quasi-harmonic approximation are the fact that the parabola used to estimate any displacement from the equilibrium value left its traces in the predictions for all the values calculated, therefore costing accuracy for the sake of flexibility and improved qualitative analysis. Other advantages of this approach include the computational simplicity and high precision.

In contrast, the molecular dynamics calculations gave a better fit to real-life thermal expansion values (relative inaccuracy of 5.4% as opposed to 17.9% with quasi-harmonic approximation), but it merely illustrated the vibrations instead of explaining their physical origin. Furthermore, the computations ran longer and often included a much larger spread of points around their approximate values.

From all this it an be concluded that both methods have their strengths and weaknesses, and it is imperative that one understands them and how both methods can be used in conjunction to achieve maximum utility.

References

[1] https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/srd/jpcrd375.pdf