Rep:Mod:gjsmodule1

Module 1: Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

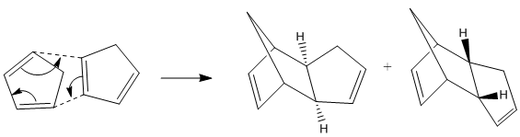

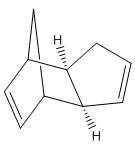

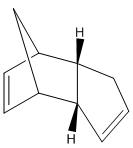

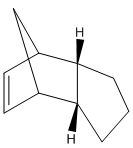

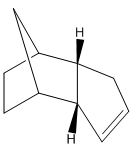

The cyclopentadienyl ligand is a common ligand in organometallic chemistry with multiple hapticities. However, it can also dimerise via a [2+4] cycloaddition reaction to form two different conformational isomers, one taking the exo form and the other the endo; a reaction which is still important for computational studies due to its integral synthetic uses [1]. By modelling both of the products and then calculating their expected energies it is possible to predict which of the two dimers should be the predominant product. The same principle can be applied to the hydrogenated dimers, again allowing informed predictions to be made about the predominance of a certain molecule. The different molecules (figure 1) and the values obtained from the MM2 calculations (figure 3) can both be seen below [2].

| Exocyclopentadiene Dimer (A) | Endocyclopentadiene Dimer (B) | Dihydro Derivative (C) | Dihydro Derivative (D) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

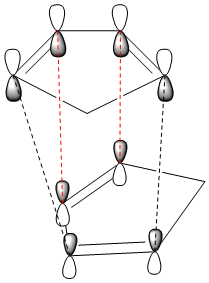

Upon inspection of the total energies of compounds A and B it can be seen that the exo product has the lower total energy with 31.8765 kcal/mol compared to 33.9975 kcal/mol for the endo product and therefore, it may be assumed to be the predominant isomer, however, this is not in fact the case under normal conditions. This is due to the stabilising effect which the endo product experiences during its formation, this is called secondary orbital overlap and a diagram of this can be seen in figure 2 in which the black dotted lines represent the forming sigma bonds, and the red dotted lines represent the stabilising interaction from the other π-orbitals.

| Compound | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.2856 | 20.5800 | -0.8383 | 7.6542 | -1.4151 | 4.2326 | 0.3775 | 31.8765 |

| B | 1.2502 | 20.8482 | -0.8359 | 9.5113 | -1.5453 | 4.3213 | 0.4478 | 33.9975 |

| C | 1.2344 | 18.9369 | -0.7609 | 12.1265 | -1.5033 | 5.7300 | 0.1631 | 35.9266 |

| D | 1.0971 | 14.5260 | -0.5493 | 12.4968 | -1.0703 | 4.5112 | 0.1406 | 31.1520 |

From figure 3 it can be seen that compound D has a much lower total energy than compound C (31.1520 kcal/mol compared to 35.9266 kcal/mol), and so is the thermodynamic product. This can be explained by looking at the large disparity in the bending energy in which compound D has ~4.41 kcal/mol more in energy. This reflects the strain felt at the sp2 hybridised carbon atoms in compound C, as the carbon atoms are part of an unconjugated 6-membered ring with an angle of 108o instead of the natural 120o angle. The sp2 hybridised carbon atoms in compound D however are part of a 5-membered unconjugated ring, with a less strained angle of 113o, thus suffering less strain and so being the thermodynamic product. However, it is not possible to predict which of the two molecules is produced via the lowest energy transition state, and so it is not possible to predict which is the kinetic product. Therefore, without this information, and without knowing to what extent the rates differ in the formation of the two molecules it is impossible to predict which is the predominant product in the hydrogenation of the endo cyclopentadiene dimer.

Stereochemistry & Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Taxol is a useful compound; it is a chemotherapy drug used to treat ovarian, breast and non-small cell lung cancer[3] as well as being used in the treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis [4] amongst other things. However, in this section Taxol itself is not to be analysed but instead some of the intermediates in its synthesis, two atropisomers which can be seen below in figure 2. The two intermediates are atropisomers as the molecule is cyclic and there is a double bond which meets a bridging bond, resulting in a high energetic barrier to ring flipping meaning that the intermediate can exist with the oxygen pointing down or up relative to the rest of the molecule in space. The intermediate which forms tends to thermally decompose to form the other atropisomer[5], suggesting that the initial intermediate formed is the kinetic intermediate and the isomer which it decomposes into is the thermodynamic intermediate. As well as there being two different intermediates, there are different conformers of the intermediates as the cyclic hexagonal ring can exist in either the chair conformation or the twist-boat conformation. Therefore, MM2 calculations and MMFF94 calculations were performed on all 4 species in order to try and determine which is the more thermodynamically favourable intermediate and which is the kinetically favoured intermediate.

| Taxol Intermediate | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy | MMFF94 Final Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 (Twist Boat) | 2.5939 | 11.4070 | 0.3575 | 20.9500 | -2.4120 | 13.9028 | -1.7109 | 45.0881 | 63.9342 |

| 9 (Chair) | 2.5510 | 11.3728 | 0.3206 | 17.3663 | -2.2609 | 12.7398 | -1.6995 | 40.3901 | 60.6308 |

| 10 (Twist Boat) | 2.7120 | 11.7434 | 0.3233 | 21.8683 | -2.1003 | 13.9183 | -2.0315 | 46.4335 | 66.3192 |

| 10 (Chair) | 2.6189 | 11.3395 | 0.3429 | 19.6784 | -2.1668 | 12.8726 | -2.0023 | 42.6830 | 60.5601 |

From looking at the results from the MM2 calculations in figure 1 above, it can be seen that the total energy of intermediate 9 is always lower than the total energy of intermediate 10 when in their respective conformations. It can also be seen that both intermediates are more energetically stable when in the chair conformation compared to the twist-boat conformation, a result which is expected as the twist-boat conformer is generally more unstable than the chair. However, there is some disparity in the results from the MMFF94 calculations as even though the total energy for intermediate 10 is greater than for 9 when in the twist-boat conformation, the total energy is greater for intermediate 9 than for 10 when in the chair conformation, although only by ~0.7 kcal/mol. It is also worth noting that there is a relatively large difference in final energy values between the MM2 results and the MMFF94 results, and this is due to the different parameters by which the calculations operate. However, as the difference between MM2 total energies when in the chair conformation is ~2.3 kcal/mol, a much greater difference than what is observed from the MMFF94 calculations and in all other cases intermediate 9 has a lower total energy than 10, it is assumed that intermediate 9 is the thermodynamic product and so intermediate 10 is the kinetic product.

| Intermediate 9 (Twist Boat) | Intermediate 9 (Chair) | Intermediate 10 (Twist Boat) | Intermediate 10 (Chair) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Intermediate 9 (Twist Boat) | Intermediate 10 (Chair) |

|---|---|

|

|

The abnormally slow functionalisation of the C=C olefinic bond of the thermodynamic intermediate is due to an effect called hyperstability [6]. This is due to the increase in steric strain experienced by the molecule when it is saturated due to the angle of the bonds at the bridging carbons. When unsaturated and the carbon atom at the bridging bond is sp2 hybridised, the angle in intermediate 9 is 124o, not too dissimilar to the natural angle of 120o for an sp2 hybridised atom. However, when saturated and the carbon atom is sp3 hybridised the angle is 122o, far from the desired 109.5o. Therefore, when saturated there is a large increase in steric strain which is energetically disfavoured meaning that the olefin bond is difficult to functionalise. The bond angles can be seen in figure 3 on the right.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Thus far mechanical molecular modelling has been used in the investigation of the stability of different isomers. However, this approach does not take into account the electronic wavefunctions of a molecule and so quickly encounters problems when dealing with slightly more taxing problems. In this section, the regioselectivity of a [1+2] cycloaddition reaction of electron deficient dichlorocarbene and compound 12 (figure 1A) is investigated by preoptimising compound 12 using the MM2 program, and then optimising it again using PM6/MOPAC, a method which approximates the valence-electron molecular wavefunctions. From this, approximate representations of the HOMO -1, HOMO, LUMO etc. were obtained, and the results can be seen in figure 2A below.

| HOMO -1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO +1 | LUMO +2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

From the HOMO it can be seen that there is a large electron density in the π-orbital of the C=C alkene bond syn to chlorine meaning that this bond is the more nucleophilic of the two double bonds, and therefore suggesting that it is this alkene bond which would undergo the [1+2] cycloaddition reaction with the electron deficient dichlorocarbene molecule. This is indeed what is observed experimentally.[7]

Further explanation for this stereospecificity for the endo product can be gathered from looking at the LUMO +1 orbital which clearly shows that the Cl-C σ* anti-bonding orbital has the correct symmetry and orientation to interact with the π-orbital of the C=C alkene bond anti to chlorine. As chlorine is relatively electronegative, this σ* anti-bonding LUMO +1 orbital is not too much higher in energy than the C=C π-orbital found at the HOMO -1 level, meaning the energy gap is small enough for a noticeable interaction to occur. This interaction results in a further stabilised molecular orbital on the C=C double bond anti to chlorine, reducing its reactivity towards the dichlorocarbene molecule. This interaction is depicted diagrammatically in figure 3A on the right.

Gaussian geometry optimization of Compound 12 and its dihydro derivative

| Compound 12 | Dihydro derivative |

|---|---|

|

|

The geometries of molecule 12 and its dihydro derivative were optimized in line with the previous methods which have been adopted, before being subjected to B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry and frequency calculations. From these results the stretching frequencies of the different bonds in the molecules became available; some of the more important stretching frequencies are reported in figure 2B below. These frequencies were taken from the IR spectra shown in figure 1B on the right.

| Compound | Stretch Freq. C-Cl (cm-1) | Stretch Freq. Anti C=C (cm-1) | Stretch Freq. Syn C=C (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound 12 | 770.84 | 1737.04 | 1757.44 |

| Dihydro derivative | 774.96 | N/A | 1758.06 |

From these results it can be seen that the C-Cl stretch for the dihydro derivative is ~4 cm-1 greater than the C-Cl stretch for compound 12, i.e. the bond is stronger. This information backs up the earlier argument that some electron density from the anti C=C π-orbital in the HOMO-1 donates some electron density into the σ* C-Cl anti-bonding orbital in the LUMO +1, as the extra electron density in the σ* orbital would destabilize the bond. However, in the dihydro derivative this π-orbital does not exist and so there is no destabilizing effect weakening the C-Cl bond, hence the frequency of absorption is slightly greater and so the bond is more stable.

Monosaccharide Chemistry: Glycosidation

In this section MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 are used in order to try and model the diastereospecificity of monosaccharides A/A*, B/B*, C/C* and D/D* in order to try and explain the almost complete stereospecificity for the reactions shown in figure 1.

The R substituent selected was a methyl group. Methyl was chosen as it is small both in terms of size and electron count meaning it facilitates a quicker and easier calculation. If a larger R substituent was selected then factors such as 1,3-diaxial compressions may have to be accounted for, as well as many other possible steric hindrances. Hydrogen was not selected as it would cause the formation of hydrogen bonds leading to more complications in the calculations. However, in this section the effects of orbital overlaps during the transition from A to C and B to D need to be considered, meaning that MOPAC/PM6 is needed in order to more correctly model the energies of the different monosaccharides. This is especially true when comparing the diastereospecificity of A/A* and B/B*.

The results can be seen below in figure 2, though it is worth noting now that it would be possible to gather very different results if the ring-flipped diastereoisomers had been analyzed instead. It is also worth noting that there may be some anomalous results due to the molecules slipping into an unwanted energy minimum during the optimization process.

| Monosaccharide | Jmol | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Charge/Dipole | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy | MOPAC/PM6 Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.2439 | 9.0495 | 0.7954 | 1.7012 | -3.7134 | 19.4035 | -2.2328 | 4.2705 | 31.5179 | -79.64831 | |

| A* | 2.2471 | 9.8482 | 0.8312 | 1.5807 | -4.0177 | 19.2264 | -0.3075 | 4.6406 | 34.0490 | -79.64647 | |

| B | 2.3412 | 13.3121 | 0.9496 | 1.2314 | -3.6958 | 18.9207 | 1.0462 | 6.2919 | 40.3973 | -69.36291 | |

| B* | 2.2759 | 9.7537 | 0.8424 | 2.1776 | -4.0674 | 19.3452 | 0.0647 | 4.0082 | 34.4003 | -64.07497 | |

| C | 2.0139 | 13.5292 | 0.6972 | 7.5264 | -2.4987 | 17.7889 | -10.2370 | -1.0047 | 27.8151 | -91.66320 | |

| C* | 2.7092 | 18.2688 | 0.8375 | 8.8618 | -2.4024 | 19.0105 | -3.2978 | -0.4355 | 43.5521 | -67.47119 | |

| D | 2.1791 | 13.7292 | 0.7111 | 9.7964 | -2.6450 | 17.6631 | -11.6706 | 1.8129 | 31.5763 | -63.13359 | |

| D* | 2.5206 | 14.7484 | 0.6701 | 8.2667 | -3.2396 | 18.9861 | -2.3289 | 2.4550 | 42.0783 | -43.19882 |

From looking at the MOPAC results there is a fairly stable trend in which the stability of the monosaccharides are as follows: A>A*, B>B*, C>C* and D>D*. However, A is only marginally more stable than A* according to the MOPAC calculation, and although most of the MM2 calculations show the same results, there is actually a reversal in stability for B and B* according to the MM2 calculation.

The large reaction completion however (nearly 100%!) when going from C to the beta anomer and from D to the alpha anomer (via the neighbouring group effect)[8] can be attributed to the extra stability of the C and D monosaccharides, compared with the C* and D* monosaccharides. These simply do not exist long enough in order to undergo the nucleophilic addition reaction which leads to the final product, due to their relative instability; an instability which can be attributed mostly to the extra strain felt at the bridges in the molecule, when the bridge is in the trans geometry rather than the cis. This is reflected in the increased bending energy for C* and D*.

Structure based Mini project using DFT-based Molecular orbital methods

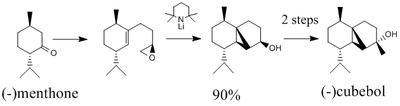

The total synthesis of (-)Cubebol

| Figure 2 | Figure 3 |

|---|---|

|

|

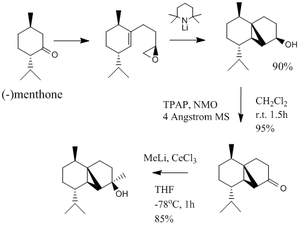

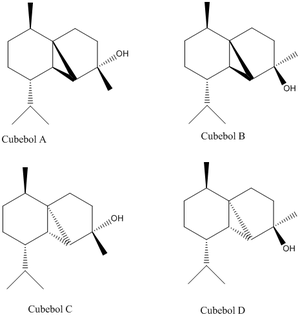

The geometry of (-)cubebol (named cubebol A for ease of nomenclature during the investigation) via its synthesis from (-)menthone is shown in figure 1 above. However, in this project I am going to investigate the possibility of the synthesis of a different isomer, cubebol B, shown in figure 2 on the right, and compare this information to that which is provided in the literature, as well as modelling (-)cubebol itself. I am also going to investigate the structures of cubebol C & D, two other isomers that could be made if the epoxide were to be facing in the opposite direction. All the geometrical isomers can be seen in figure 3.It is also worth noting that it would have been equally valuable to investigate the intermediates in the reaction scheme in order to try and dissect the reasons behind the large regioselectivity of the reaction mechanism.[9].

13C NMR Spectra

To begin with, the isomers were optimized using MM2 and MOPAC/AM1 before being minimised using DFT/mpw1pw91. From these optimized models of the four isomers, NMR data was collected as shown in figures 4 & 5 below.

| Molecule A | Molecule B | Molecule C | Molecule D |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Carbon Number | δ Literature Cubebol A (ppm) [10] | δ Cubebol A (ppm) | δ Cubebol B (ppm) | δ Cubebol C (ppm) | δ Cubebol D (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80.3 | 78.8 | 79.3 | 77.5 | 76.6 |

| 2 | 44.1 | 50.2 | 45.0 | 46.4 | 47.9 |

| 3 | 39.0 | 41.1 | 39.4 | 43.6 | 43.3 |

| 4 | 36.3 | 40.2 | 38.0 | 41.4 | 41.9 |

| 5 | 33.6 | 39.6 | 36.8 | 37.4 | 36.8 |

| 6 | 33.4 | 37.3 | 35.7 | 36.3 | 35.6 |

| 7 | 31.7 | 35.3 | 32.3 | 36.1 | 35.4 |

| 8 | 30.8 | 31.9 | 32.3 | 35.6 | 34.8 |

| 9 | 29.5 | 31.5 | 31.7 | 33.3 | 33.3 |

| 10 | 27.9 | 30.0 | 29.4 | 31.1 | 30.3 |

| 11 | 26.5 | 25.0 | 27.6 | 27.1 | 29.2 |

| 12 | 22.5 | 23.0 | 26.8 | 26.3 | 25.8 |

| 13 | 20.1 | 21.3 | 22.4 | 23.8 | 23.1 |

| 14 | 19.6 | 21.1 | 21.4 | 20.6 | 20.4 |

| 15 | 18.7 | 20.5 | 20.0 | 19.0 | 19.1 |

If the data for cubebol A and B are first considered, it can be seen that interestingly it is cubebol B that correlates more closely to the literature values when the chemical shifts are relatively large (i.e. for carbon atoms 1-7), before it is cubebol A which begins to represent the literature values more closely out of the two isomers. This makes it very difficult to decipher any meaningful results, and could be due to the heavier oxygen atom (when compared to carbon and hydrogen atoms) which has skewed the calculation. Therefore, corrections may need to be made to the NMR data.

No literature values for cubebol B, C or D was found, but when comparing C and D it can be seen that there values are again very similar, and as the 13 C NMR probably needs some correction due to the presence of the oxygen atom, it is difficult to use the data with any certainty in order to decipher between the two isomers. However, it can be seen that all the isomers follow a very similar pattern from carbon 1 to 15, and that there are large differences between A and C, A and D, B and C and B and D. This means that the direction of the cyclopropane face can be detected from the data, which is a useful tool, and with some corrections for the heavier oxygen atom and some very diligent analysis, it could also be used to separate A from B and C from D.

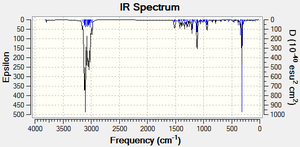

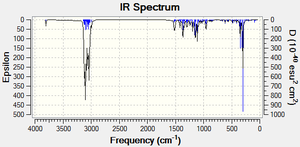

Infrared Spectra

From the IR data, it can be seen that there are some fairly large differences between the O-H bond strength of the 4 isomers. Going from strongest to weakest the order is: D>A>C>B. This suggests that there are some differences in orbital overlaps and therefore molecular orbitals (as we know there has to be) between the 4 isomers. With this knowledge therefore, the molecules were optimized using MM2 and then MOPAC/PM6 in order to inspect their respective molecular orbitals to look for some electron donation or acceptance with an O-H orbital. However, no orbitals became apparent which were similar in energy and also had the correct symmetry and orientation in order to interact. The energies derived from the MOPAC/PM6 were also very similar: -81.27305 Kcal/Mol for cubebol A, -82.97835 Kcal/Mol for cubebol B, -82.80648 Kcal/Mol for cubebol C and -81.61080 Kcal/Mol for cubebol D, interestingly suggesting that cubebol B is actually more energetically stable than cubebol A. However, as discussed earlier the MOPAC program also has its flaws and so cannot be trusted as data on its own.

| Cubebol A | Cubebol B | Cubebol C | Cubebol D |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Isomer | Literature Stretch Freq. O-H[11] | Stretch Freq. O-H (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Cubebol A | 3380 | 3799.03 |

| Cubebol B | - | 3795.08 |

| Cubebol C | - | 3796.28 |

| Cubebol D | - | 3802.21 |

References

- ↑ William L. Jorgensen, Dongchul Lim, and James F. Blake, J. Am. Chem. SOC. 1993, 115, 2936-2942

- ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:organic

- ↑ http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Cancerinformation/Cancertreatment/Treatmenttypes/Chemotherapy/Individualdrugs/Paclitaxel.aspx

- ↑ Patent no:5583153, Filing Date: 6 Oct 1994, Issue Date: 10 Dec 1996

- ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:organic

- ↑ Alan B. McEwen and and Paul von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. SOC. 1986, 108, 3951-3960

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ Tomoo Nukada, Attila Berces, Marek Z. Zgierski and Dennis M. Whitfield, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 13291-13295

- ↑ David M. Hodgson, Saifullah Salik, and David J. Fox, J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 2157–2168

- ↑ Bin Wu, Takehiro Kashiwagi, Ikuhiro Kuroda, Xiao Hui Chen, Shin-ich tebayashi & Chul-Sa Kim, J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 2157–2168

- ↑ Bin Wu, Takehiro Kashiwagi, Ikuhiro Kuroda, Xiao Hui Chen, Shin-ich tebayashi & Chul-Sa Kim, J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 2157–2168