Rep:Mod:ga714

Introduction

The potential energy surface for the species involved in a reaction is riddles with maxima and minima. Some understanding of the transition state, reactant approach orientation or products is required to obtain an optimised transition structure and, therefore, a clear picture of the reaction profile. During this experiment, a variety of methods for obtaining this transition structure were used. Method one was a guess at the transition structure and a direct optimisation of this to arrive at the saddle point. Method two involved first optimising this guess at the transition state to a local minimum with select frozen co-ordinates and a subsequent optimisation to obtain the desired structure. Method three involved first creating the product, optimising this structure, then breaking the bonds that are formed in this reaction and moving the two species apart slightly. This formed a structure resembling the transition state and from this point method two was carried out. It is clear that method one is the fastest and simplest method to adopt, however, it proved difficult to obtain such a good visual approximation of the transition state that Gaussian was able to calculate the structure without errors. Method three was the most indirect method, but by far the most reliable. The correct orientation of the reacting molecules in this method is inherent as the estimate was created from the product, and so a detailed knowledge of the transition state was not required. For all the reactions except for that in exercise 1, method three proved to be the most fruitful. This is a result of the species being more complex, and so, a direct route to the optimised transition structure became more difficult. Furthermore, in Exercise 2, the transition state, product and reactants were optimised using two different levels of optimisation, PM6 and B3LYP/6-31G(d) respectively. The PM6 level of optimisation is much quicker but less accurate that that of the B3LYP/6-31G(d). The two have different reference points for the calculated energies under the heading 'Thermochemistry' and so the values cannot be directly compared but relative energies can be. Intrinsic Reaction Co-ordinate (IRC) calculations were carried out to illustrate the progress of the reaction from one local minimum, through the transition state saddle point, and to another minimum.

Exercises 1, 2 and 3 all involve a class of pericyclic reactions, namely [4+2] cycloadditions. The Diels-Alder reactions can be recognised as normal or inverse electron demand.[1] Normal electron demand is when the strongest bonding interaction involves the combination of the diene HOMO and dienophile LUMO. However, if the diene is bonded to an electron-withdrawing group, lowering the energy of the HOMO and LUMO, and the dieneophile is bonded to electron-donating groups, raising the energy of the HOMO and LUMO, inverse electron demand will be observed. This is when the strongest bonding interaction involves overlap of the HOMO of the dienophile and LUMO of the diene. Cheletropic reaction is the other type of reaction investigated in this experiment. The thermodynamics and kinetics of the reaction were compared to those of the Diels-Alder cycloadditions.

Minimum

A minimum is a point on a potential energy surface at which in all dimensions the force constant is negative. However, this does not mean that it is the lowest point on the potential energy surface. The lowest point on a potential energy surface is known as the global minimum, otherwise the point is a local minimum.

Transition State

A transition state is the point of a potential energy surface where the force constant is negative in only one dimension and in all other dimensions it is positive. In 2D this manifests itself as a saddle point, where the reaction pathway is the dimension with positive force constant.

Cheletropic Reaction[3]

A cheletropic reaction is a type of cycloaddition reaction where two new sigma bonds are formed to a single atom from the terminal atoms from a fully conjugated system.

Nf710 (talk) 21:32, 14 December 2016 (UTC) Great intro but you havent said that the force constant is the second derivative of the PES.

Computational Methods

The Different Methods of Optimisation

The semi-empirical PM6 method has pre-set values for certain common integrals. This reduces the number of integrals that need to be evaluated, thus, significantly reducing the time required for the program to run but decreasing the accuracy of the result. The DFT B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of optimisation has a hamiltonian that is a function of charge density. Below is the exchange correlation part of the Hamiltonian for the B3LYP method. This is the part of the Hamiltonian that cannot be solved analytically with Density Functional Theory.

It is clear that exchange correlation of the B3LYP function involves evaluating the integrals via the Hartree-Fock method. This method uses a hamiltonian that is a function of r. These calculations can have a multitude of dimensions and, therefore, evaluating all of the integrals in the matrix as a function of their position is extremely time consuming. The B3LYP function takes the ab initio Hartree-Fock method and adds some corrections, as the Hartree-Fock method overestimates the energy. This leads to much longer processing times when optimising using the B3LYP method relative to the PM6 level of optimisation. For example, when optimising the transition structures in Exercise 2, using the B3LYP level of optimisation the run time was about an hour whereas with the PM6 level it was four minutes. Therefore, for the purpose of the following qualitative analysis the PM6 level of optimisation alone was sufficient for Exercises 1 and 3. Nevertheless, if a more quantitative analysis was required, the B3LYP method would yield more accurate results.

Nf710 (talk) 21:35, 14 December 2016 (UTC) Good attempt at explaining the methods.

Exercise 1: Reaction of Butadiene with Ethylene

This experiment involved the formation of cyclohexene via a Diels-Alder reaction. The transition state, reagents and product were all optimised using a PM6 level calculation.

MO Analysis

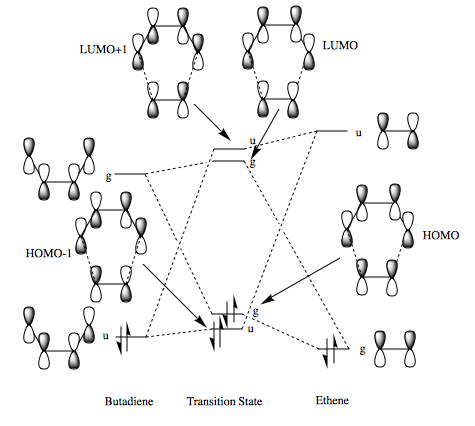

Analysing the molecular orbitals produced as a result of the PM6 calculation allowed the MO diagram above to be constructed. From the Jmols below, it can be seen that the HOMO of butadiene and the LUMO of ethene are the same symmetry, ungerade, as are the LUMO of butadiene and the HOMO of ethene, however, they are gerade. This is a key observation as orbitals of different symmetry have an overlap integral of zero, and therefore do not mix. Orbitals of the same symmetry can mix and form new bonding and antibonding MOs. Consequently, it is the mixing of one of these pairs that will form the HOMO and LUMO of the transition state.

The HOMO-1 and LUMO+1 of the transition state clearly show the result of an interaction between the butadiene HOMO and the ethene LUMO. This is an example of normal electron demand. The sizes of the orbitals in the transition state HOMO-1 show a larger butadiene contribution, this shows that the butadiene HOMO is lower in energy and contributes from to the bonding MO of this interaction. Furthermore, the HOMO of ethene and LUMO of butadiene are close enough in energy to interact, but not to change the order of the MOs. These MOs combined to form the HOMO and LUMO MOs of the transition state.

The MOs of the transition state involve unfavourable interactions, and so, the energy of the MOs in the transition state are higher that the MOs of the reactants. This is to be expected as we know that the transition state is the highest energy point on a reaction profile.

| Butadiene | Ethene | Transition State | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bond Length Analysis

| C-C Bonds | Bond Length (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Butadiene/Ethene | Transition State | Cyclohexene | |

| C1-C2 | 1.4683 | 1.4111 | 1.3378 |

| C2-C3 | 1.3354 | 1.3798 | 1.5007 |

| C3-C4 | N/A | 2.1143 | 1.5403 |

| C4-C5 | 1.3273 | 1.3818 | 1.5409 |

| C5-C6 | N/A | 2.1151 | 1.5403 |

| C6-C1 | 1.3354 | 1.3797 | 1.5007 |

| Lit.[4] Bond Length (Å) butadiene double=1.338 single=1.454 ethene=1.3305 | |||

The table shows that the butadiene and ethene double bonds get longer as the reaction progresses through the transition state. This demonstrates the breaking of the pi bonds and subsequently the formation of new C-C single bonds. The butadiene single bond gets shorter as the change in hybridisation, from sp3 to sp2, of the two carbons and the formation of a pi bond occurs. At the transition state, the formation of the new C-C single bonds has already begun as the distance between the carbons is about 2.11 Å and the Van der Waals' radius of one carbon atom is 1.7 Å. The fact that the carbon atoms are within 2 Van der Waals' radii of eachother indicates that there is some level of interaction occurring between carbons 3 and 4, and, 5 and 6 in the transition state. Additionally, it appears that the calculation underestimates the effect of conjugation and subsequent delocalisation in butadiene. Delocalisation results in the slight lengthening of the double bonds and shortening of the single bonds. The PM6 calculation got a smaller value for the butadiene double bonds and a larger value for the single bond compared to the experimental literature values.

Vibrational Modes

The .gif file above is an animation of the imaginary vibrational frequency calculated in the TS (Berry) optimisation. It shows the terminal carbons of butadiene and the ethene carbons moving towards eachother and maintaining symmetry. This movement is that which the two molecules follow in the formation of the cyclohexene product. The symmetry being maintained throughout this movement shows that the bonding is synchrous. This is in good agreement with that which is expected from a concerted Diels-Alder cycloaddition.

Below is the animation of the first real vibrational frequency. It is clear that this vibration occurs in a different plane to the imaginary vibration and that this twisting motion has nothing to do with bond formation.

Nf710 (talk) 21:47, 14 December 2016 (UTC) Very Well answered exercise, including the TS state MO

Exercise 2: Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

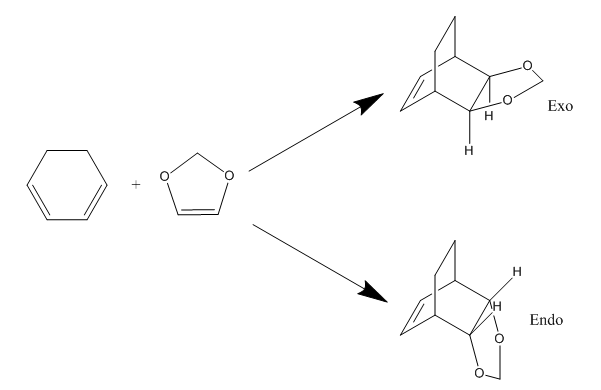

The following experiment involved the Diels-Alder reaction between cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole. This resulted in the formation of two products, the exo and endo adducts. Only a change in approach orientation resulted in the formation of a different product. All reagents, transition states and products were optimised at the PM6 and B3LYP levels. The optimisation at the B3LYP level was much more expensive for the transition state than it was for the products and reagents.

MO Analysis

For this cycloaddition, the dienophile had particularly high energy HOMO and LUMO. This was a result of the electron-donating nature of the two oxygen atoms adjacent to the double bond. This resulted in the LUMO of the dienophile being too high in energy to interact significantly with the HOMO of the diene. However, the HOMO of the dienophile had a more comparable energy level with the LUMO of the diene and a good overlap was observed through the HOMO and LUMO of the transition states. Both the endo and exo transition state HOMOs show a slightly larger contribution from the dieneophile HOMO, meaning that this molecular orbital is slightly lower in energy than the diene LUMO. The outcome of this overlap is an example of inverse electron demand.

| Exo Transition State HOMO and LUMO | Endo Transition State HOMO and LUMO | Dieneophile HOMO | Diene LUMO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

(These are the MOs for PM6. With B3LYP, it would be clearer to see the secondary orbital interactions Tam10 (talk) 11:50, 5 December 2016 (UTC))

Thermodynamics

The table below shows the calculated activation and reaction energies for the formation of the both the exo and endo products at the PM6 and B3LYP level. Firstly, it should be made clear that regardless of the level of calculation the relative position of the energy does not change. For example, at both the PM6 and B3LYP level, the exo activation energy is greater than that of the endo. Therefore, for a qualitative analysis and determination of the thermodynamic and kinetic products, a PM6 level calculation is sufficient. It is clear that the exo adduct is the thermodynamic product. Therefore, if the reaction were allowed to equilibrate the major product would be the exo one as it is the lower energy product. Yet, the kinetic product is the endo adduct, as it has a lower energy barrier to reaction. The transition state of the endo product is believed to be stabilised by secondary orbital interactions between the groups bonded to the alkene in the dienophile and the rear of the diene (see below table). This means that for an irreversible Diels-Alder reaction, the endo product is formed.

Additionally, the difference between the calculated energies between the two optimisation levels is greatest for the activation energy. This means that the transition state is much lower in energy than calculated at the PM6 level and was exemplified by the time taken for the B3LYP optimisation of the PM6 optimised transition state. Therefore, if thorough quantitative analysis of the reaction thermodynamics and kinetics were to be performed, a PM6 calculation would not be suitable.

| Reaction Adduct and Optimisation Level | Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | Reaction Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Exo PM6 | 195.09 | -69.90 |

| Exo B3LYP | 117.91 | -65.15 |

| Endo PM6 | 192.56 | -70.35 |

| Endo B3LYP | 110.21 | -68.75 |

The sp2 hybridised oxygen has a lone pair located in a p-orbital. In the approach that results in the endo product, this p-orbital is in a position where it can overlap with the rear of the diene, as visualised in the diagram above with the dotted arrows. This interaction between the p orbital and the pi bond results in a stabilising of the endo transition state. This rationalises the lower activation energy of the endo Diels-Alder reaction. For the exo approach the oxygen p-orbitals are too far away from the rear of the diene and so a secondary orbital effect is not observed. Therefore, the activation energy of the exo approach is greater.[5]

Nf710 (talk) 21:58, 14 December 2016 (UTC) This section was done very well and concisely and your understanding of the theory is excellent f

Exercise 3: Diels-Alder Vs Cheletropic

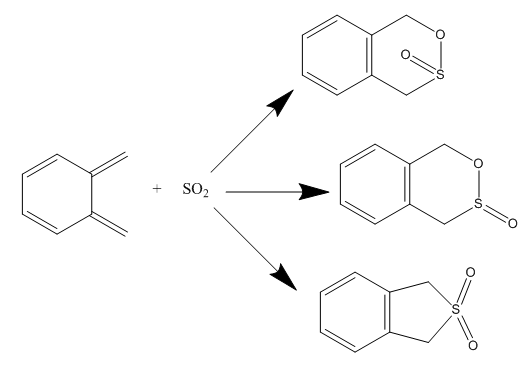

This experiment involved the investigation of the approach orientation on the type of cycloaddition reaction that occurred as well as the product that was formed. For the reaction between sulfur dioxide and o-xylylene, there were three products identified: the exo and endo products of the Diels-Alder [4+2] cycloaddition and the product of the cheletropic reaction.

IRC Analysis

Below are the .gif file animations of the IRC. These show the synchronous nature of the cheletropic reaction and the asynchronous nature of the Diels-Alder reaction.

| Exo IRC | Endo IRC | Cheletropic IRC |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Exo .log file File:IRC.LOG

Endo .log File File:IRCENDO.LOG

Cheletropic .log file File:IRCCHELE.LOG

Thermodynamics

| Reaction Class and Adduct | Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | Reaction Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

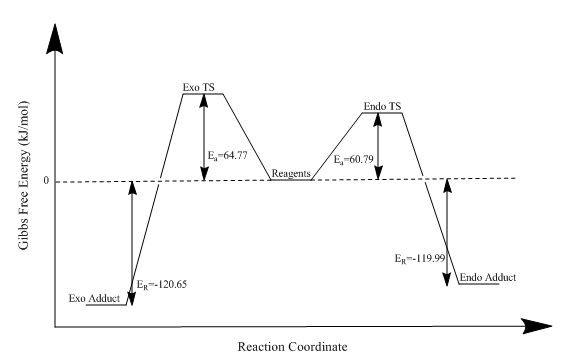

| Diels-Alder Exo | 64.77 | -120.65 |

| Diels-Alder Endo | 60.79 | -119.99 |

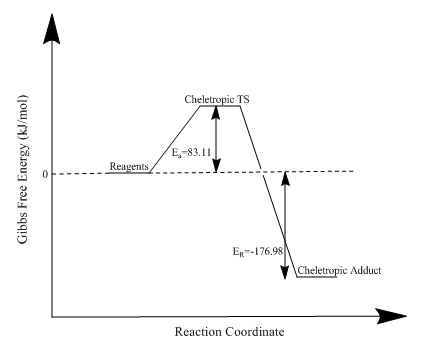

| Cheletropic | 83.11 | -176.98 |

Reaction Profiles

Using the data obtained, it is clear that, once again, the exo adduct is the thermodynamic product and the endo adduct is the kinetic product. By altering the reaction conditions it is possible to favour the formation of one over the other. The transition state of the endo product is stabilised by secondary orbital effects. The activation energies and reaction energies can be visualised in the reaction profiles below. The cheletropic reaction has a large activation energy but is also the most thermodynamically stable product. The large activation energy is a result of the formation of a strained five-membered ring. The thermodynamic stability relative to the Diels-Alder product is a consequence of the presence of the sulfonyl group. The enthalpic contribution of the extra strong S=O bond gives the cheletropic product its thermodynamic stability.

| Exo and Endo Diels-Alder Reaction Profiles | Cheletropic Reaction Profile |

|---|---|

|

|

(Good, clear diagrams. It's obvious to see what you're explaining. For more than 2 pathways you can still put them on the same diagram so that they can all be compared Tam10 (talk) 11:50, 5 December 2016 (UTC))

Xylylene Instability

In the IRC animations for the Diels-Alder reactions, the formation of a delocalised pi-system, preceding bond formation, is observed. This pi-system is very similar to that of benzene and is very stable. Consequently, xylylene is not a particularly stable species as the formation of a delocalised pi-system drives its reactions. Below the mechanism for the electrocyclic reaction that results in the formation of benzocyclobutane is outlined. Woodward-Hoffman rules state that, for a reaction to be thermally allowed, there must be an odd number of (4q+2)s and (4r)a components. In the xylylene system under investigation, there are four pi-electrons and the orbitals overlap in antarafacial fashion (as shown below). This means there are zero (4q+2)s and one (4r)a and so the reaction is thermally allowed. Subsequently, a conrotatory mechanism is observed. The formation of the benzocyclobutane product is thermodynamically favourable for the aforementioned reasons and the reaction energy is shown in the table below. Furthermore, it would appear possible that o-xylylene could react with itself as it could act as the diene and the dienophile in a Diels-Alder reaction. However, conjugation of the double bonds would indicate that it may not be an ideal dienophilic substrate.

(This reaction is thermally forbidden. As you've shown, it has a large barrier. The first sentence of this paper shows the use of UV to force the reaction. This paper actually shows the difficulty of the reaction as the Diels-Alder dimerisation tends to occur first Tam10 (talk) 11:50, 5 December 2016 (UTC))

| Reaction | Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | Reaction Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Xylylene Aromatisation | 143.82 | -53.12 |

Alternative Diels-Alder Reaction Pathway

O-xylylene has a second diene site, however, the inability of the product to have a stabilising delocalised pi-system means that these exo and endo products are relatively unfavourable. In the previous exercises, it has been shown that the endo and exo products are not too dissimilar in energy. Therefore, from the result below for the reaction energy to form the alternative endo product, which is far less than the reaction energies displayed in the previous table, it can be said that this is a relatively poor site for Diels-Alder [4+2] cycloaddition. A consequence of this is that there is not a great thermodynamic driving force for the reaction.

| Reaction Class and Adduct | Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | Reaction Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Diels-Alder Alternative Endo Site | 91.01 | -4.72 |

Conclusion

Through these experiments it was found that a direct attempt at optimising a transition state is extremely unreliable as soon as the transition state configuration is not trivial. Furthermore, that the PM6 level calculations are very good at obtaining quick qualitative results. However, it is not suitable for good quantitative study, particularly when calculating transition state energies. For the two reactions investigated the endo product was the kinetic product due to stabilising secondary orbital effects in the transition state.

References

- ↑ J. Clayden, N. Greeves and S. Warren, Organic Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 2nd edt.

- ↑ Image taken from http://sf.anu.edu.au/~vvv900/gaussian/ts/ 24/11/16.

- ↑ PAC, (Glossary of terms used in physical organic chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 1994)), 1994, pp 1094

- ↑ N. C. Craig, P. Groner, and D. C. McKean, J. Phys. Chem. Ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jp060695b 110, 7461 (2006)

- ↑ P. V. Alston , R. M. Ottenbrite , J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 1111–1116.