Rep:Mod:fv611

Introduction

The aim of this experiment was to get familiar with various techniques within chemical modelling and successively apply these to rationalise the outcome of certain reactions and explore the properties of molecules. Modelling also gives us the tools necessary to predict NMR data and chiroptical measurements of molecules, and to use these predictions as useful insights towards determining the real structure of these molecules. Such analysis was then applied to the syntheses performed in experiment 1S, the synthetic component of this experiment, which involved asymmetric epoxidation of the same alkenes discussed in part 2 of this wiki.

All calculations presented in this wiki have been excecuted using Avogadro and Gaussian 9. The energy calculations computed by Avogadro have been based on the MMFF94s[1] Force Field, while the geometry optimizations has been done using the Conjugate Gradients method. Some characteristics of this specific Force Field are worthy of note as it will make the specific discussion flow more easily.

Molecular Mechanics compute the structure and energy of molecules based on the nuclei's movement only, considering the electrons only indirectly, following the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. This treatment is roughly comparable to considering a molecule and its bonds as a collection of weights connected with springs. Within this method, interaction between particles are described using potential functions, different for each type of interaction considered, derived from classical mechanics. These functions rely on experimentally derived parameters, unique to specific sets of atoms. A force field is defined as the ensemble of potential functions and parameters chosen to be applied, and the sum of interactions given by the force field that we choose to apply determine the conformation of atom-like particles. Force fields give a value for the steric energy of a specific molecule and generally take the form of where the total energy is shown as the sum of the energies respectively associated with bond stretching, bond angle bending, bond torsion,nonbond interactions and specific terms such as hydrogen bonding for example. The underlying principle behind the use of force fields is that although we need quantum mechanics to describe bonding accurately we can still approximate bonding with simple physical models.[2]

MMF94s, the static form of the Merck Molecular Force Field, is a computational model that accurately describes conformational and inter-molecular interaction energies but yields planar or nearly-planar equilibrium geometries. [3] This force field is accurate for both gas phase and condensed phase calculations and is highly transferable. The internal bonded terms that it uses are bond stretching, angle bending, stretch-bending, torsional energy and out of plane bending, while the nonbonded terms include Van der Waals and electrostatics. [2]

The Bond stretching energy goes up whenever a bond is compressed or stretched from its equilibrium position, by a value that can be approximated using an alternative to Hooke's law; similarly the Angle Bending energy is related to the deviation in potential energy when moving away from the strain free energy of a particular angle. These two energies usually differ by about an order of magnitude, reflecting the ease of distorting angles rather than bonds.

Out-of-plane bending is very similar to Angle bending and represents the potential energy needed to move an atom out of a plane. Additionally, the torsional potential energy term represent the ease of rotation a bout a specific bond, is modelled using a Fourier Series term and depends on the co-sinus of the torsional angle and such can be negative (unless correction is applied). [4]

Since Bond Stretching and Angle bending are not really independent, an additional Stretch-Bending Energy term is introduced, representing the coupling between the two former motions.

The two nonbonded energy contributions are easier to understand and represent the sum of the attractive and repulsive interactions between parts of the molecule due either Van der Waals forces or electrostatic (coulombic) forces respectively.

All considered, it is relatively easy to understand how a high steric energy value is a signal of instability and how inspecting the total energy of a set of optimized structures and the different contributions of each energy term can lead to a good understanding of why certain reactions tend to yield specific products.

Conformational analysis using Molecular Mechanics

Studies on Cyclopentadiene Dimers

The Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

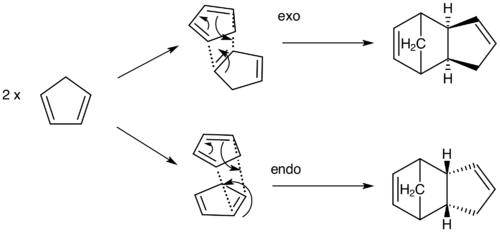

Cyclopentadiene is a small organic molecule, which is particularly popular in organometallic synthesis as its deprotonated form is a very useful ligand [6]. As depicted in Scheme 1, it can undergo two stereoisomeric Diels-Alder ( [π4s + π2s] cycloaddition) pathways leading to dimerisation. This type of addition can lead to two two possible dimers: one in which the diene and the dienophile are positioned next to each other (exo) and the other in which they are above one another (endo). The aim of this part of the experiment is to establish if the dimerisation happens under kinetic or thermodynamic control by analysing the energy of the optimized geometries. As for all equilibrium process, the thermodynamic product would be formed by the overall tendency to equilibrate the reaction towards the lowest energy isomer, while the kinetic product would be formed due to the stability of the transition state, which would require a lower activation energy [7]

Geometry optimizations and MMFF94s energy calculations have been performed on both dimer conformations and the results are summarized in Table 1, which also include 3D structures of each conformer.

| Exo-dicyclopentadiene | Endo-dicyclopentadiene | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| units: [kcal/mol] |

|

| ||||||

| Bond Stretching Energy | 3.54318 | 3.46792 | ||||||

| Angle Bending Energy | 30.77257 | 33.18932 | ||||||

| Stretch Bending Energy | -2.04142 | -2.08218 | ||||||

| Torsional Energy | -2.73099 | -2.94950 | ||||||

| Out-of-plane Bending Energy | 0.01476 | 0.02183 | ||||||

| Van der Waals Energy | 12.80165 | 12.35873 | ||||||

| Electrostatic Energy | 13.01367 | 14.18454 | ||||||

| Total Energy | 55.3742 | 58.19067 |

As mentioned by Woodward and Katz [8], the favoured steric product is the one which has the largest number of unsaturated centers in the presumed transition state, i.e. the endo-dimer.

This is thought to be due to the stabilization of the transition state by the electrons that are not involved in the bond-forming process.

As we can see from our computed results this isomer has a higher optimized energy, indicating that it would not be formed if the reaction was happening under thermodynamic control (since such conditions will yield the most stable isomer, i.e. the one with the lowest energy[9]). The only logical deduction to make here is that the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene happens under kinetic control and therefore tends to yield the endo-isomer.

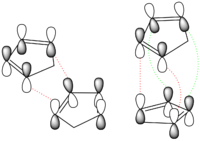

The reason why the more sterically hindered dimer (endo-form) is kinetically favoured is the presence of stabilizing secondary orbital interactions betweene the diene frontier orbitals and the π bond of the dienophile in the endo-dimer which are not compatible with its exo-form.

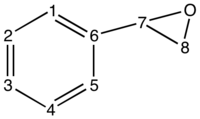

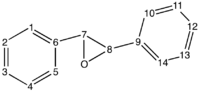

See Figure 1 for a pictorial representation of the HOMO-LUMO interactions (the primary orbital interactions are in red and the secondary ones in green).

Further analysis of the computed energies leads to the observation that the biggest contributor to the energy difference is the Angle Bending Energy . This could be due to the difference in the deviation from ideality of the C-Ĉ-C angle at the junction of the two rings. Indeed in the case of the endo-dimer this angle is further from the ideal sp3 hybridised centre angle of 109.5°, which means that the destabilisation of this product is more important than for the exo-dimer.

The Hydrogenation of Dicyclopentadiene

Since the dimer has two double bonds, hydrogenation can happen on two different sites. Each possible product has been modelled, along with the double hydrogenation product,the tetrahydro alkane. The results of these calculations are shown in Table 2 .

| Cyclopentene dehydrogenation product | Norbornene dehydrogenation product | Tetrahydro derivative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| units: [kcal/mol] | |||

| Bond Stretching Energy | 3.31163 | 2.82311 | 4.61252 |

| Angle Bending Energy | 31.93343 | 24.68536 | 47.46318 |

| Stretch Bending Energy | -2.10213 | -1.65719 | -2.55720 |

| Torsional Energy | -1.46862 | -0.37840 | -1.16379 |

| Out-of-plane Bending Energy | 0.01310 | 0.00028 | 0.00000 |

| Van der Waals Energy | 13.63879 | 10.63732 | 17.13363 |

| Electrostatic Energy | 5.11950 | 5.14702 | 0.00000 |

| Total Energy | 50.44569 | 41.25749 | 65.48833 |

These results coincide with the empirical data reported by the literature: the ratio of hydrogenation of the double bond within the norbornene ring is several times faster than the the bond situated in the cyclopentene ring [10]. Energy calculations for both these alkene products corroborate this hypothesis, in particular the notably lower energy (and related higher thermodynamic stability) of the norbornene hydrogenation product.

A closer analysis of Avogadro's results leads to the realisation that the stabilization of the latter alkene is mainly due to the change in Angle Bending energy. The higher rotational flexibility of the cyclopentene-containing product might be due to the conformational lock in the other possible hydrogenation product, imposed by the double bond in the hexane ring. The presence of more rigid sp2 carbons might make ring twisting more difficult, raising the energy necessary for rotation in the norbornene compound. An alternative explanation might be the higher stability of bond angles in the cyclopentene compound: where the sp2 angles in the norbornene compound will be unnaturally forced to less than their ideal value of 120°, the 5-mebered ring will provide a higher, more stable value.

Another significant reason for energy difference between the two possible products is strenght of the Van der Waals interactions, weaker in the cyclopentene compound. This might be explained by considering the spacial distribution of the hydrogens along the saturated rings. In the case of the cyclopentene-containing compound, the hydrogens in the 6-membered ring are likely to be more spaced apart than they would be in the 5-membered ring of the norbornene-like product.

Since the thermodynamic product is formed, we can conclude that the hydrogenation of dicyclopentadiene happens under thermodynamic conditions.

Agreeing with experimental results, the energy for the optimized tetrahydro product is a lot higher than the one of either alkene, explaining the difficulties in obtaining the doubly-reduced alkane (also logically predictable since this product needs twice as much reactant). It might be worth noting that in the saturated compound the Out-of-plane Bending Energy and the Electrostatic Interactions are zero. These observations are both trivially explainable: the absence of double bonds forbids the creation of a rigid plane, so what would be "Out-of-plane" bending is notably less energy demanding and is included in the Angle Bending term (which is indeed quite high); additionally not having pi-electron clouds avoids coulombic interactions intra- and inter-molecularly.

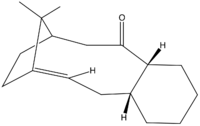

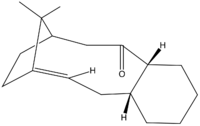

The two compounds illustrated above are first mentioned by Paquette et al. [11] as intermediates towards the synthesis of Taxol, an anti-cancer drug particularly effective in the cure of ovarian and breast cancer [12]. Their original synthesis was done through a reversible oxy-Cope rearrangement [11].

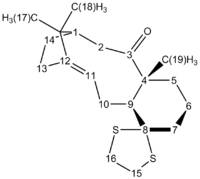

As there are numerous structural features in both compounds 1 and 2 (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 respectively), there are various possible axis of comparison to be followed in the discussion of their relative stability and the energies of their isomers.

| Atropisomer 1 (chair conformer) | Atropisomer 2 (chair conformer) | |

|---|---|---|

| units: [kcal/mol] | ||

| Total Energy | 70.54098 | 60.55270 |

These two compounds are atropisomers, essentially conformers that interconvert slowly or not at all (because of electronic and steric constraints, for example due to the restricted rotation around a single covalent bond) to be observed or even isolated in some cases [13] [14]. A very good review of the role of atropisomers in drug synthesis can be found here. The very first observations we can make are based on the relative stabilities of both atropisomers, in which the restricted rotation about the C-C bond at the ring junction results in the carbonyl group pointing towards the isopropyl bridge or opposite to it.

The computed energies (as can be seen in Table 3) underline the stability of compound 2. Those results are not surprising since the steric hindrance on the side of the plane that contains the iso-propyl bridge is much higher, rationalising the preferred configuration as the one in which the alkane bridge and the carbonyl are on opposite sides of the plane. Since one of the biggest contributions to the energy difference is again the Angle Bending Energy we can hypothesise that when the carbonyl group is pointing "down" the bond angles around the sp2 will be more favourable (closer to the natural bond angle).

Since this is an oxy-Cope rearrangement, happening at equilibrium [11], the most thermodynamically stable atropisomer should form majorly. From our results it looks like this is Atropisomer 2 so we will conduct all further investigations on derivatives of this compound.

| Atropisomer 1 (twist-boat conformer) | Atropisomer 2 (twist-boat conformer) | Atropisomer 1 (H-isomer) | Atropisomer 2 (H-isomer) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| units: [kcal/mol] | ||||

| Total Energy | 92.18541 | 68.87626 | 77.35182 | 61.03434 |

The second structural feature worth noting is the conformation of the hexane ring. This can either be optimized to a Chair conformation or a Twist-Boat one (for additional information on hexane conformations, see this paper by D. J. Nelson and C. N. Brammer (2011)). The Boat and Half-Chair conformers are not explored here because Avogadro recognizes them as unstable transition states rather than intermediates.

The energy calculations for these conformers are tabulated in Table 4 and as expected the chair conformation is energetically the most favoured. It is interesting how the energy difference between the two conformers is higher for the least stable atropisomer ( vs ).

The third structural aspect that has been investigated in this module is the position of the hydrogen substitute on the double bond: the former can indeed be pointing either in the same direction as the carbonyl group or opposite to it. This change in position has little influence on the overall energy (probably due to the small size and weight of the hydrogen molecule) but as before we can see that the difference in energy between the two isomers of Atropisomer 1 is about 7 times bigger than the energy difference between the two isomers of Atropisomer 2.

A completely separate comparative approached started from noticing the exceptionally low energy of Compound 2 . The number resulted from MMFF94s seems in fact incredibly low when thinking about the steric energy computed for the endo-dicyclopentadiene (the latter is only ca 2 kcal/mol lower!). We would expect a larger, more polar and more sterically hindered molecule to have a much higher energy compared to the hydrocarbon dimer.

With the aim of exploring this exceptional stability, we investigated three isomers of Compound 2 , to explore the effects of displacing the double bond within the 10-membered ring (alkene isomers 1 and 2 in Table 5 ) and of moving it within the hexane ring (alkene isomer 3 in Table 5 ). We also computed the energy of the saturated derivative of the compound in question. We chose to work on derivatives of the most stable of the two atropisomers to provide a computational model for molecules that would be easier to synthesize.

Results of the aforementioned computations are presented in Table 5 .

| Alkene isomer 1 | Alkene isomer 2 | Alkene isomer 3 | Alkane derivative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| units: [kcal/mol] | ||||

| Total Energy | 71.37076 | 97.59182 | 75.44373 | 74.50069 |

Although the results tabulated above might seem unreasonable when compared with Compound 2, a similar alkene with an , a closer analysis of the structures and the available literature will shed light on them.

While Compound 2 and all of its three alkene isomers have the same molecular structure, Compound 2 is the only one containing a bridgehead olefin. This particular family of compounds has been extensively researched in the literature[15][16]and found to have an exceptional stability, which explains why the alkene in question is more stable than even its saturated derivative (going against the trend seen in section 2 of alkanes tending to have a lower energy).

This incredible stability is due to the parameter defined as Olefinic Strain (OS) by Lesko & Turner [17] i.e. the strain associated with the C=C bond, one of the two contributions to the energy strain value of bridgehead olefins (the other being the strain imposed by the hydrocarbon skeleton). OS is considered a measure of the olefin instability [18] and can be defined as the difference between the total strain energy of the bridgehead alkene in its most stable conformation and its hydrogenated (saturated) derivative, also in its most stable conformation. As we can see this particular compound has a negative Olefinic Strain: it contains less strain than its hydrogenated parent compound (as predicted by Schleyer [16]). The negative OS defines a relatively new class of hyperstable olefins which are characteristically unreactive, because of their specific cage structure[19] and the positioning of the double bond at the bridgehead, rather than to enhanced π bond strenght or steric hindrance [20]. This enhanced stability is the reason why the functionalisation of the alkene in the next step towards Taxol synthesis is reported to happen slowly[11].

From further dwelling into the different contributions to the ΔE between the saturated compound and the bridgehead olefin, we can see that the Angle Bending Energy term is once again to blame. This can be rationalised by considering the large deviations in angle amplitude from the ideal sp3 value of 109.5deg in the alkane compound. In its alkene parent, some of these angle are between sp2 carbons and hence their computed value is closer to the ideal one, suppressing a large amount of strain in the molecule.

We can also rationalise the order of stability of the three alkene isomers: the least stable is the alkene with the double bond being within the largest ring, and the most stable is understandably the alkene with the double bound positioned closest to the bridging iso-propyl.

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

The aim of this part of the module was to relate empirical spectra to computed ones, and such judge the relative efficiencies and accuracies of both methods. All NMR predictions have been run on Gaussian 9, and submitted to the HPC super computer.

The previous results have established that the chair conformation of Atropisomer 2 is the most stable so we can reasonably expect Compound 3 (see Figure 4 ) to have the lowest energy between the two atropisomers.

We computed the H and C NMR of Compound 3 and compared it to the literature values.

1H NMR Comparison

It is easy to be quite confused by the results (DOI:10042/27552 ) produced by the HPC super computer but a visualisation as above might help spot the similarities rather than the differences.

There are quite a few points to consider when doing a comparaison of this type, between a computed NMR and the data from a manually run one found in the literature[21].

First of all a computed NMR is "static": it is base on a fixed picture of the molecule, a model quite distant from the real situation, where NMR are taken in a dynamic environment that allows the molecule to rotate freely about its single bonds. The major implication of this approximation is that the HPC considers all methyl groups as individual, while any "real" NMR would consider them as being in an equivalent environment. To correct for this the chemical shifts computed by the HPC as being respectively at (0.90, 0.97, 1.57ppm), (0.97, 1.23, 1.57ppm) and (0.60, 1.23, 2.31ppm) have been averaged to the following values: δ1.38ppm, δ1.26ppm, δ1.15ppm and set with an integration equivalent to 3H. The exact spectrum produced by Gaussian can be seen here, the above comparative image has been constructed on gNMR and modified in Word.It shows the reference values in red and the averaged computed ones in black.

The literature peaks for this compound are quite difficult to assign given the high number of complex multiplets. The presence of these splitting patterns in the empirical data might be due to the cyclic nature of the compounds, that locks the conformation of the hydrogens along the ring and forces them to experience germinal (2J) (CHECK) in addition to the expected 3J coupling.

All the above considered, the averaged chemical shifts of the protons on Carbons 17, 18 and 19 can be compared to the three literature shifts between δ1.10 - 1.03ppm. Although it is hard to assign exactly which peaks correspond to which set of 3 methylic protons since all three carbon environments are quite similar, we can confirm a satisfactory agreement with the literature since the averaged chemical shifts only differ by about 0.2 ppm.

The vinylic proton is expected to have a quite specific shift between δ6 and δ5 ppm, which makes it easy to identify it as the 5.95ppm value computed (cf. δ5.21ppm in the lit.). The reason why the computed chemical shift is higher than the experimental data might be that Gaussian doesn't consider the shielding effect due to the Van der Waals interactions with other Hydrogen molecules in the compound. This also would explain why the difference between the literature shift and the computed shift of the proton in question in the chair conformer is much higher than the difference with the shift computed for the same proton in the twist-boat conformation (see later): the latter conformer has less Van der Waals interactions and hence a much lower discrepancy in results.

The chemical shift reported in the literature at 1.58 is easily to assign as the Hydrogen on C(9) since we would expect it to have a doublet of doublets splitting pattern due to the coupling with the two Hydrogens on C(10).

Due to the limitations of computational chemistry, mainly in recognizing splitting patterns (maybe the degeneracy tolerance of G09 could be increased to give a more detailed spectra) we cannot go further in the analysis of the computed 1H NMR, but we have found quite a few starting points for discussion.

It might be put forward that one of the reasons for the difference in chemical shifts and patterns encountered when comparing literature values and computed ones is that the molecules on which the NMR was recorded experimentally was not actually in its lowest energy configuration. Hence we have also modelled the twist-boat conformer of the same atropisomer and computed the predicted NMR spectra using the same method, and presented in the picture below as before, with the same reference values in red and the gNMR averaged spectra in black (the methylic protons, considered as being in different environments by Gaussian as can be seen in the result spectrum here).

We can see that the computed values are closed to the empirically obtained spectra than before, suggesting that Compound 3 is actually found in its twist-boat conformation.

Of course the opposite could also be true (the chair optimized conformer is not the geometry with lowest possible energy). Unfortunately if this is the case, the error lies within the optimization algorithm and the only way to explore this aspect would be to try modelling the same compound with another program of the same type hence going out of the scope of this particular experiment.

13C NMR Comparison

| Chair conformer spectrum | Twist-Boat conformer spectrum | Literature values[21] |

|---|---|---|

| 211.06 | 211.06 | 211.49 |

| 147.94 | 148.57 | 148.79 |

| 120.03 | 118.62 | 120.9 |

| 93.64 | 88.68 | 74.61 |

| 60.46 | 67.55 | 60.53 |

| 54.77 | 56.07 | 51.3 |

| 53.94 | 55.4 | 50.94 |

| 49.54 | 49.92 | 45.53 |

| 49.15 | 46.59 | 43.28 |

| 46.66 | 44.29 | 40.82 |

| 41.89 | 41.24 | 38.72 |

| 41.73 | 37.45 | 36.78 |

| 38.52 | 36.16 | 35.47 |

| 34.05 | 31.99 | 30.84 |

| 33.61 | 29.09 | 30 |

| 28.09 | 28.62 | 25.56 |

| 26.44 | 25.85 | 25.35 |

| 24.4 | 25.1 | 22.21 |

| 22.61 | 23.28 | 21.39 |

| 21.57 | 21.7 | 19.83 |

The above Table lists the chemical shifts of the 13C NMR of the two conformers of Compound 3, along with the reported literature values for the same shifts. From the analysis of these data set we can calculated that almost all computed chemical shifts are within ±5ppm of the literature values [21] except from the carbons closer to the sulfur ring substituent, i.e. C(8), to which we can assign the literature chemical shift that most differs to the computed values for both conformers (δ74.61ppm). It is interesting that when considering the twist-boat conformer we can notice that it has one more computed chemical shift that differs significantly from the literature values: we can assign this shift (δ60.53ppm) to either of the hexane ring carbons adjacent to the sulfur-ring substituent (C(9) or C(7)), since one of these will be closer to the heavy atoms due to the specific structure of the conformer (the presence of Oxygen on the carbonyl group also has an influence but its exact impact is complex to define). Only an adequate specific correction to compensate for the heavy atoms influence will yield more accurate computed NMR spectra.

We calculated an average absolute difference between the chemical shifts reported in the literature and the computed ones and found that overall the twist-boat conformer is the closest (av. Δ(chair) = 3.51 vs av. Δ(twist-boat)=3.03). This can be considered as reasonably solid proof that Compound 3 is actually found in the twist-boat conformation.

Analysis of the Properties of the Synthesised Alkene Epoxides

The second part of this experiment consisted in the investigation of the properties of two catalytic systems used in the epoxidation of alkenes and their`Transition States, coupled with the exploration of the chiroptical properties of these epoxides. The alkenes selected for these studies are the ones that were synthesized in during the 1S experiment. The predicted 1H and 13C NMR were predicted for each alkene using the same methods and parameters used in Part 1 of this module.

The Two Catalytic Systems and their Crystal Structure

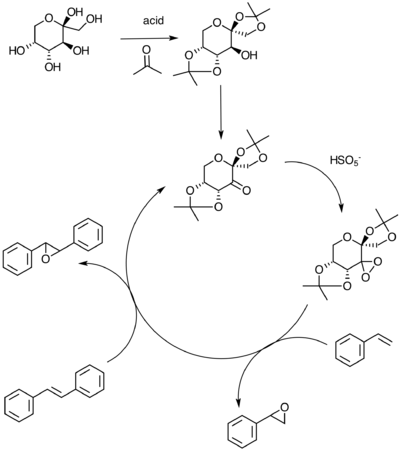

In the undergraduate laboratory, two asymmetric catalysts were synthesized, commonly known as the Jacobsen's catalyst and the Shi's catalyst. Although both catalyst perform the same epoxidation reaction on the alkenes, their structure and the mechanism they undergo is different. A search for the crystal structure of these two complexes has been done on the Cambridge Crystal Database (CCDC) using COnQuest and the results were visualized on Mercury. Each structure implicates different selectivities: the Shi catalyst has a trans-selectivity, while Jacobsen's is known to have a cis-selectivity [22]

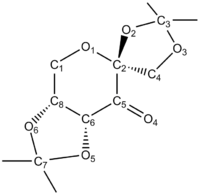

The Shi Asymmetric Fructose Catalyst

Scheme 2 above shows the catalytic cycle for the Shi catalyst, synthesized by Shi et al.[23] in 1997. Derived from fructose, this catalyst reacts through conversion (in presence of oxone) to a dioxirane intermediate that successively acts on the alkene to oxidise it. A search for this catalyst within the CCDC has yielded the NELQEA unit cell (seen in Figure 5). A 3D model of the Shi pre-catalyst can be seen by clicking

.

The structure of this catalyst depends quite a lot on stereoelectronic interactions, the most important and object of this part of the module being the anomeric effect . This effect comes from the donation of electron density from the oxygen lone pair, nO into the antibonding σ* MO on a neighbouring C-O bond. The steric requirement for this type of interactions mean that th donor orbital has to be antiperiplanarly aligned to the acceptor orbital for ideal (maximum) overlap. Usually the substituents in a 6-membered ring system will prefer to adopt an equatiorial position (thus minimising the 1,3-diaxial repulsions), but when an anomeric centre is present the increased stability derived from it overcomes the destabilising effects of diaxial repulsion, favouring the alignement of the acceptor groups in an axial position.

We can predict the locations of anomeric effects within a molecule by examining the various CO bond lengths: donation of electron density into the antibonding orbitals weakens it, thus lengthening it. Considering a typical CO bond length to be 1.43 Å, analysing the bond lengths through Mercury shows that there are 3 longer CO bonds. We can therefore conclude that there are three anomeric interactions in this complex. CO bond lengths are reported in Table 7 . None of the other bond lengths are deviate from what is expected.

| C-O bond | lenght (Å) | C-O bond | lenght (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C(1) - O(1) | 1.429 | C(5) - O(4) (double bond) |

1.213 |

| C(2) - O(1) | 1.42 | C(6) - O(5) | 1.419 |

| C(2) - O(2) | 1.53 | C(7) - O(5) | 1.442 |

| C(3) - O(2) | 1.46 | C(7) - O(6) | 1.43 |

| C(3) - O(3) | 1.406 | C(8) - O(6) | 1.428 |

| C(4) - O(3) | 1.406 |

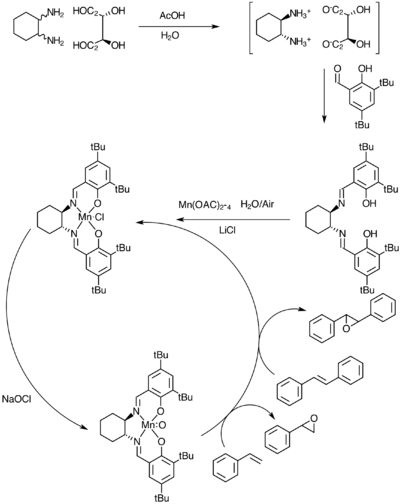

The Jacobsen Asymmetric Catalyst

Scheme 3 above depicts the catalytic cycle for Jacobsen’s catalyst. While the general picture is agreed on, there are quite a few options when considering the direction of approach of the alkene towards the catalyst . A few steric considerations might help in assessing what direction would be the most favourable. It was therefore decided to examine the non-covalent intramolecular interactions within the catalyst. As we can see from the space-filling model ( Figure 7 ) all sides of the molecule are pretty much blocked up for access except for the space in between the two ter-butyl groups.

To decide if it would be plausible for the alkene to approach in such a direction the focus has been directed on the Van der Waals interactions between the H-groups on the previously mentioned tBu groups. See for a visualisation of the distances between these atoms. One of these distances (2.o8o A) is shorter than the sum of the VdW radii (2.40 A) and hence is repulsive. This means that the groups bearing the concerned atoms will tend to position themselves as far apart from each other as possible. It can therefore be envisaged that an approach of therefore be envisaged that an approach of the alkene through these groups is possible

The Calculated NMR Properties of the Synthesized Alkenes

Styrene Oxide

| Computed 1H shift (ppm) DOI:10042/27558 (spectrum) | Literature value [24] | Computed 13C shift DOI:10042/27558 (spectrum) | Literature value [24] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.55 (1H) | 2.75 (dd, 1H) | 53.476 | 51.0 (C(8)H2) |

| 3.12 (1H) | 3.08 (dd, 1H) | 54.059 | 51.1(C(7)H) |

| 3.66 (1H) | 3.80 (dd, 1H) | 118.267 (C1) | 125.3 (2xCH) |

| 7.49 (4H), 7.30 (1H) | 7.24 - 7.33 (m, 5H) | 122.948 (C5 &C3) | 128.0 (CH) |

| 123.413 (C4) | 128.2 (2xCH) | ||

| 124.131 (C2) | |||

| 135.144 | 137.5 (C6) |

Table 8 compares computed and literature values of the NMR spectra of Styrene epoxide. All values are close enough to assume that the computed and empirical spectra were run on the same conformer. Assignement of the peaks is trivial and corresponds to what is expected.

Trans-Stilbene Oxide

| Computed 1H shift DOI:10042/27559 (spectrum) | Literature value [24] | Computed 13C shift DOI:10042/27559 ( spectrum) | Literature value [24] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.538 | 3.87 (s,2H) | 66.42 | 62.8 (2 x CH (C7+C8)) |

| 7.479 (8H), 7.57(2H) | 7.25 - 7.59 (m, 10H) | 118.264 (C5-C10) | 125.5 (4xCH) |

| 123.075 (C1-C14) | |||

| 123.212 | 128.3 (2xCH (C3-C12)) | ||

| 123.51 (C2-C13) | 128.5 (4 xCH) | ||

| 124.222 (C4-C11) | |||

| 134.091 | 137.1 (2xC (C9+C6)) |

Again, all the chemical shifts for the NMR spectra of Transtilbene oxide found in the literature match up quite nicely with the computed ones, proof that the literature and the computed conformer coincide.

Assigning the Absolute Configurations of Styrene and Transtilbene Oxide

Literature vs. Computed values for Optical Rotatory Power

| λ = 589nm; solvent:chloroform | Computed ORP | Literature Value |

|---|---|---|

| Styrene Oxide | -30.41deg DOI:10042/27560 | -33.33 deg [25] |

| Transtilbene Oxide | +297.98deg DOI:10042/27561 | +296deg [26] |

Using the Calculated Properties of Transition States for the Reactions to Determine Enantiomeric Excess

Since asymmetric epoxidation happens under kinetic control the transition state with the lowest energy will lead to the enantiomer that is formed in excess. Finding calculating the Gibbs free energy of reaction for the interconversion between the two lowest energy enantiomeric transition states allows us to calculate the equilibrium constant for such interconversion. Since the equilibrium constant is essentially the ratio between products and reactants at equilibrium, it will tell us how swayed is the composition of the mixture from its racemic state. This leads to calculation of the enantiomeric excess for each epoxide formed and allows for comparison with the literature. A useful conversion factor to remember is .

Although calculations made for Transtilbene oxide match the literature values almost exactly, the results for Styrene Oxide are more ambiguous. In fact, the value of the enantiomeric excess is the same as the literature for both Shi [27] and Jacobsen [28], but the enantiomer that is predicted to be in excess has an S- configuration, while both literature sources mention say it would be the R one or they do not specify. Two causes for the difference can be thought of: either the literature is plainly wrong or the catalyst used in the literature is in fact the mirror image of the one computed and so the ratio between the enantiomers is inverted.

All the energies of the Transition States have been computed by Prof. Rzepa and can be found here.

All calculations of K and ee are specified in the sections below.

Styrene Oxide - Shi Catalyst

| R-Series | S-Series |

|---|---|

| -1303.730238 | -1030.733828 |

| -1303.730703 | -1303.724178 |

| -1303.736813 | -1303.727673 |

| -1303.738044 | -1303.738503 |

ΔG between lowest energy isomers: (TS4(S) - TS4(R)

Since we have . This yields of a 0.38 to 0.62 R:S ratio fraction of the enantiomers, which means a 24% ee of the S enantiomer.

Styrene Oxide - Jacobsen Catalyst

| R-Series | S-Series |

|---|---|

| -3343.960889 | -3343.969197 |

| -3343.962162 | -3343.963191 |

ΔG between lowest energy isomers: (TS1(S) - TS2(R)

Since we have This yields of a 0.00058251 to 0.99941749 R:S ratio fraction of enantiomers, which means a 99.88% ee of the S enantiomer.

Transtilbene Oxide - Shi Catalyst

| R,R-Series | S,S-Series |

|---|---|

| -1534.687808 | -1534.683440 |

| -1534.687252 | -1534.685089 |

| -1534.700037 | -1534.693818 |

| -1534.699901 | -1534.691858 |

ΔG between lowest energy isomers: (TS3(R,R) - TS3(S,S)

Since we have This yields of a 0.001378 to 0.99862 S,S:R,R ratio fraction of the enantiomers, which means a 99.72% ee of the R,R enantiomer (lit. value >95% [27]).

Transtilbene Oxide - Jacobsen Catalyst

| R,R-Series | S,S-Series |

|---|---|

| -3574.921174 | -3574.923087 |

ΔG between lowest energy isomers:

Since we have

This yields of a 0.11656 to 0.883439 R,R: S,S ratio fraction of the enantiomers, which means a 76% ee of the S,S-enantiomer (lit.value: 33%) [29].

Investigating the Non-Covalent Interactions in the Active-Site of the Reaction Transition State

An NCI analysis was done on the lowest energy Transition state of R,R-Transtilbene during the Shi epoxidation, depicted in Figure 11.The bond forming region is clearly evident in the picture (in blue), but the proper non-covalent interactions are the one in green (corresponding to mildly attractive interaction regions). Not only we can see the absence of repulsive interactions, we can also appreciate how the attack of the catalyst happens only on one side of the alkene and so two classes of stereoisomers will be possible. Additionally we can predict the region with attractive interactions to be sensitive to the conformation of the phenyl rings.

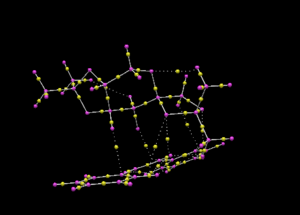

Investigating the Electronic Topology (QTAIM) in the Active-Site of the Reaction Transition State

All yellow points in Figure 12 are technically Bond Critical Points, but only those connected to carbon atoms (in purple) through solid lines correspond to covalent bonds. The dotted lines correspond to hydrogen bonds. Since BCP represent the maximum electron density within a bond it is logical for them to be roughly midways through C-C bonds, and one would expect them to be displaced towards the most electronegative atom when there is a difference in polarity between two elements forming a bond.

References

- ↑ T.A. Halgren,"MMFF VI. MMFF94s option for energy minimization studies", J Computational Chem, 20, 7, 720-729, DOI:<720::AID-JCC7>3.0.CO;2-X 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199905)20:7<720::AID-JCC7>3.0.CO;2-X

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 K. I. Ramachandran, G. Deepa, K. Namboori, "Computational Chemistry and Molecular Modeling", Soringer, 2008

- ↑ P. J. Winn, G. G. Ferency, C. A. Reynolds, "Towards Improved Force Fields:III.", J. Computational Chem, 20,7, 704-712, DOI:/10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199905)20:7

- ↑ D. Lai Gwai Cheung, "Structures and Properties of Liquid Crystals and Related Molecules from Computer Simulation", Ph.D Thesis, University of Durham, Chemistry Department, 2002

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 All schemes and chemical figures have been drawn by the author on ChemDoodle especially for this experiment.

- ↑ J. Okuda, "Bifunctional Cyclopentadyenil Ligands in Organotransition Metal Chemistry", Comments on Inorganic Chem, 16, 4, 185-205, (1994)

- ↑ M. A, Fox, J. K. Whitesell, "Organic Chemistry", Italic text, James and Barlett, 2003

- ↑ R.B. Woodward, T. J. Katz, "The mechanism of the Diels-Alder reaction", Tetrahedron, 5(1), 1959, Pages 70–89, DOI:10.1016/0040-4020(59)80072-7

- ↑ "Organic Chemistry" M.A. Fox, J.K. Whiteshell, pp287-289

- ↑ D. Skála1 and J. Hanika, "Kinetics of Dicyclopentadiene Hydrogenation, using Pd/C catalyst", Petroleum and Coal, 45, 105-108, (2003)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319; DOI:[1]

- ↑ D. G. I. Kingston , G. Samaranayake and C. A. Ivey, "The Chemistry of Taxol, a clinically useful anti-cancer agent", Journal of Natural Products, 1990, 53, 1-12

- ↑ N. L. Allinger, E. L. Eliel, S. H. Wilen, M. Ōki, "Recent Advances in Atropisomerism", Topics in Stereochemistry, 14, (2007), DOI:10.1002/9780470147238.ch1

- ↑ P. Lloyd-Williams,E.Giralt, Chem. Soc. Rev.,30, 145, (2001)

- ↑ K. J. Shea,"Recent developments in the synthesis, structure and chemistry of bridgehead alkenes", Tetrahedron Letters, 36, 1683-1715, (1980), DOI:10.1016/0040-4020(80)80067-6

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 W. F. Maier, P.V. Schleyer, " Evaluation and prediction of the stability of bridgehead olefins", J Am Chem Soc, 103, 1891-1900, (1981), DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ P. M. Lesko, R. B. Turner, "Strain energy in bicyclo[3.3.1]non-1-ene", J Am Chem Soc, 90, 6888, (1968), DOI:10.1021/ja01026a084

- ↑ D. J. Martella, M. Jones Jr., P. Schleyer, W.F. Maier, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,101, 7634, 1979, Template:DOI:10.1021/ja00519a038

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. Von Rague Schleyer,"Evaluation and Prediction of Stability in Bridgehead Olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc.,103, p1891 (1981), DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,103, p1891 (1981), DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 L. A. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, "[3.3] Sigmatropy within 1-vinyl-2-alkenyl-7,7-dimethyl-exo-norbornan-2-ols. The first atropselective oxyanionic Cope rearrangement", J. Am. Chem. Soc.,112 (1), pp 277–283, (1990), DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ja003049d

- ↑ http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 C.Wiles,M. J. Hammond, P. Watts, "The development and evaluation of a continuous flow process for the lipase-mediated oxidation of alkenes", Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2009, 5, DOI:10.3762/bjoc.5.27

- ↑ F. R. Jensen, and R. C. Kiskis, "Stereochemistry and Mechanism of the Photochemical and Thermal Insertion of Oxygen into the Carbon-Cobalt Bond of Alkyl(pyridine)cobaloximes", I974

- ↑ A. Solladié-Cavallo, A. Diep-Vohuule,"A two-step asymmetric synthesis of pure trans-(R,R)-diaryl-epoxides", Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 7,(1996), Pages 1783–1788, {{DOI|10.1016/0957-4166(96)00213-3}

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Y. Tu , Z. Wang , and Y. Shi,"An Efficient Asymmetric Epoxidation Method for trans-Olefins Mediated by a Fructose-Derived Ketone", J. Am. Chem. Soc.,118 (40), pp 9806–9807, (1996), DOI:10.1021/ja962345g

- ↑ M. Palucki, P. J. Pospisil, W.Zhang, E. Jacobsen, "Highly Enantioselective, Low-Temperature Epoxidation of Styrene", J Am Chem Soc , 116, 9333, (1994)

- ↑ W. Zhang, J. L. Loebach , S. R. Wilson, E. N. Jacobsen, "Enantioselective epoxidation of unfunctionalized olefins catalyzed by salen manganese complexes", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112 (7), pp 2801–2803, DOI:10.1021/ja00163a052