Rep:Mod:frapnt19

In this report the program Gaussian will be used in order to build, optimise and analyse simple inorganic molecules.

In the first part, NH3 will be discussed in order to learn how to run an optimisation, understand it and critically check that it has been done in a correct and sensible way. N2 and H2 will then be optimised and analysed: the data obtained will be used together with the information about ammonia to investigate the reaction energies of the Bosch-Haber process, which is widely used in industry to produce ammonia.

The last part of the report will be an analysis of the water molecule (H2O) and its Molecular Orbitals (MOs)and a brief additional analysis of O2.

NH3 Molecule

Key information

Dynamic image of the molecule

Figure 1. 3D representation of NH3 molecule |

Optimisation data

Table 1. Important information about the optimisation process and the optimised molecule.

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| E(RB3LYP) | -56.55776873 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000485 a.u. |

| Point Group | C3V |

| Optimised N-H Bond Distance | 1.01798 Angstroms |

| Optimised H-N-H Bond Angle | 109.471 degrees |

Table 2. "Item" table, taken from the optimisation file produced by Gaussian and used to check that the optimisation has run properly (all the forces have to converge, maximum force on any atom should not exceed 0.00045 au, and the average (RMS) force should not exceed 0.0003 au).

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000004 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000072 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000035 0.001200 YES

You can find the optimisation file here.

Molecular vibrations

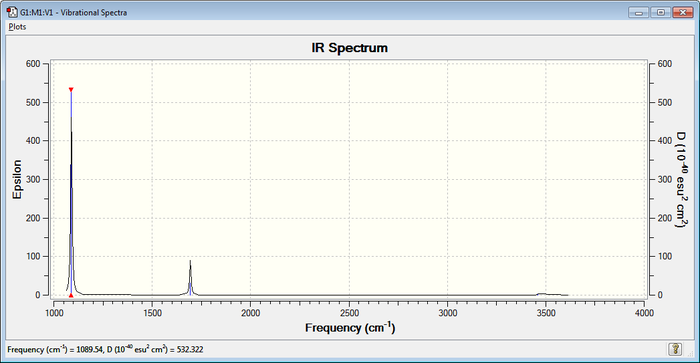

The 3N-6 rule predicts 6 modes for the molecule being analyzed: 3(4) - 6 = 6.

Modes 2 and 3 are degenerate and modes 5 and 6 are degenerate too (they have the same energy).

Modes 1,2 and 3 are "bending" vibrations and modes 4,5 and 6 are "stretching" vibrations.

Mode 4 is highly symmetric.

Mode 1 is known as the "umbrella mode".

2 bands would be expected in the experimental spectrum of gaseous ammonia: in fact, the values of the Infrared column in the above tab for modes 4,5 and 6 suggest that the intensity of the bands is very little and thus not visible, and this is due to the fact that the stretching vibrations do not induce a strong enough change in dipole and are therefore IR inactive.

IR Spectrum

Charge analysis

Charge N-atom = (-1.125)

Charge H-atoms = (0.375)

Charges calculated by computational methods are as expected: in fact, N has a negative charge because is more electronegative than H, which instead presents a positive charge.

N2 Molecule

Key information

Dynamic image of the molecule

Figure 4. 3D representation of N2 molecule |

Optimisation data

Table 3. Important information about the optimisation process and the optimised molecule.

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| E(RB3LYP) | -109.52412868 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000060 a.u. |

| Point Group | D*H |

| Optimised N-N Bond Distance | 1.10550 Angstroms |

Table 4. "Item" table, taken from the optimisation file produced by Gaussian and used to check that the optimisation has run properly (all the forces have to converge, maximum force on any atom should not exceed 0.00045 au, and the average (RMS) force should not exceed 0.0003 au).

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000001 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000000 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000000 0.001200 YES

You can find the optimisation file here.

Molecular vibrations

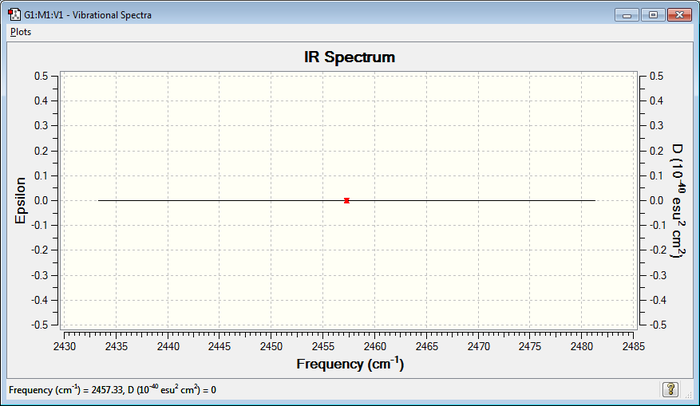

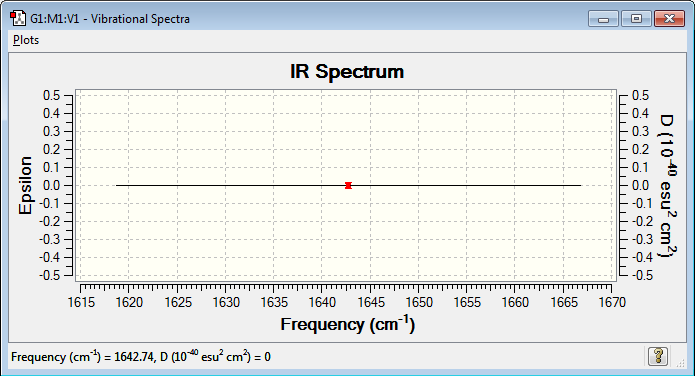

IR Spectrum

The analysis of the vibrations in this molecule shows that they do not cause any change in dipole and they are therefore IR inactive (no bands seen on the spectrum).

H2 Molecule

Key information

Dynamic image of the molecule

Figure 7. 3D representation of H2 molecule |

Optimisation data

Table 5. Important information about the optimisation process and the optimised molecule.

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| E(RB3LYP) | -1.17853936 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000017 a.u. |

| Point Group | D*H |

| Optimised H-H Bond Distance | 0.74279 Angstroms |

Table 6. "Item" table, taken from the optimisation file produced by Gaussian and used to check that the optimisation has run properly (all the forces have to converge, maximum force on any atom should not exceed 0.00045 au, and the average (RMS) force should not exceed 0.0003 au).

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000000 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.001200 YES

You can find the optimisation file here.

Molecular vibrations

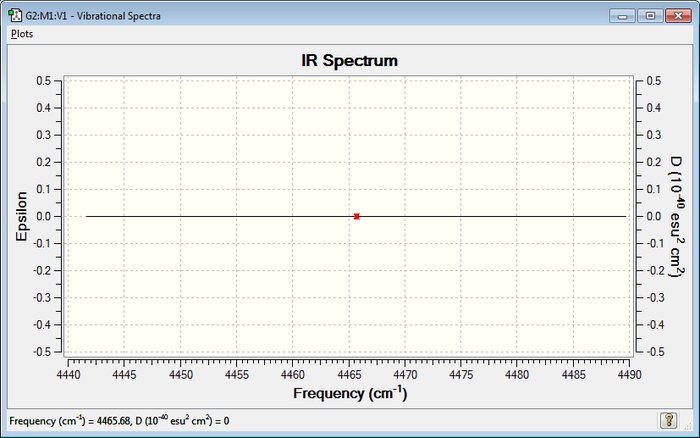

IR Spectrum

The analysis of the vibrations in this molecule shows that they do not cause any change in dipole and they are therefore IR inactive (no bands seen on the spectrum).

The Haber-Bosch Process

Using the values calculated in the previous sections of this report, it is now possible to calculate the energy for converting hydrogen and nitrogen gas into ammonia gas. In industry this reaction is known as the Haber-Bosch Process and it is fundamental because it allows large-scale production of ammonia, which is a crucially important fertilizer.

Reaction energies

N2 + 3H2 -> 2NH3

E(NH3)= -56.55776873 a.u.

2*E(NH3)= -113.11553746 a.u.

E(N2)= -109.52412868 a.u.

E(H2)= -1.17853936 a.u.

3*E(H2)= -3.53561808 a.u.

ΔE=2*E(NH3)-[E(N2)+3*E(H2)]= -0.0557907 a.u. = -146.48 kJ/mol

The reaction is exothermic, so energy is given out during the process and the product (NH3) is more stable than the reactants (H2 and N2): ammonia is in fact at lower energy.

H2O Molecule

Key information

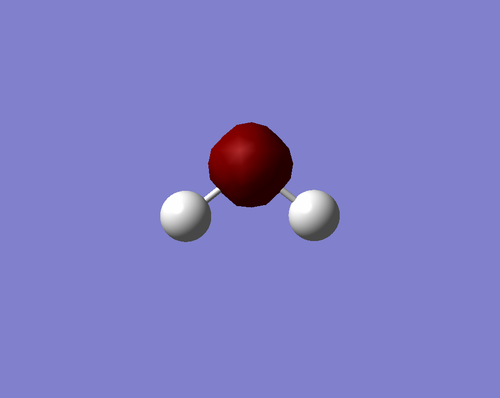

Dynamic image of the molecule

Figure 10. 3D representation of H2O molecule |

Optimisation data

Table 7. Important information about the optimisation process and the optimised molecule.

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| E(RB3LYP) | -76.41973740 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00006276 a.u. |

| Point Group | C2V |

| Optimised O-H Bond Distance | 0.96522 Angstroms |

| Optimised H-O-H Bond Angle | 103.745 degrees |

Table 8. "Item" table, taken from the optimisation file produced by Gaussian and used to check that the optimisation has run properly (all the forces have to converge, maximum force on any atom should not exceed 0.00045 au, and the average (RMS) force should not exceed 0.0003 au).

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000099 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000081 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000115 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000120 0.001200 YES

You can find the optimisation file here.

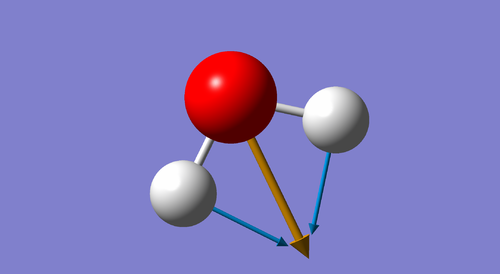

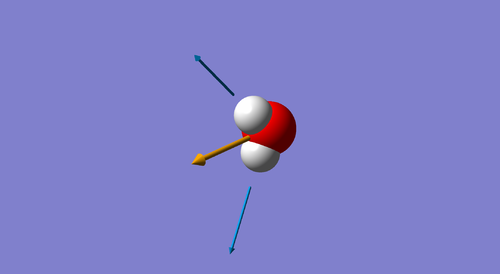

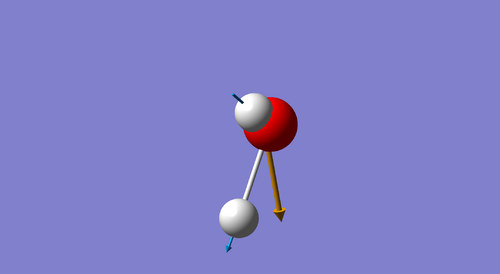

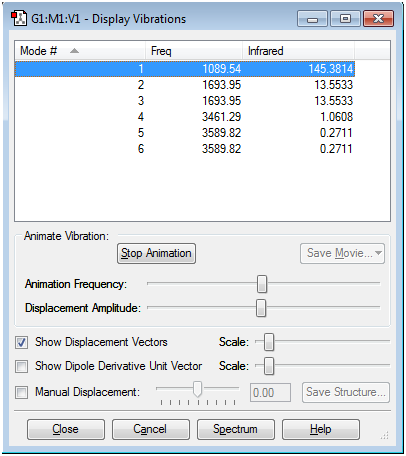

Molecular vibrations

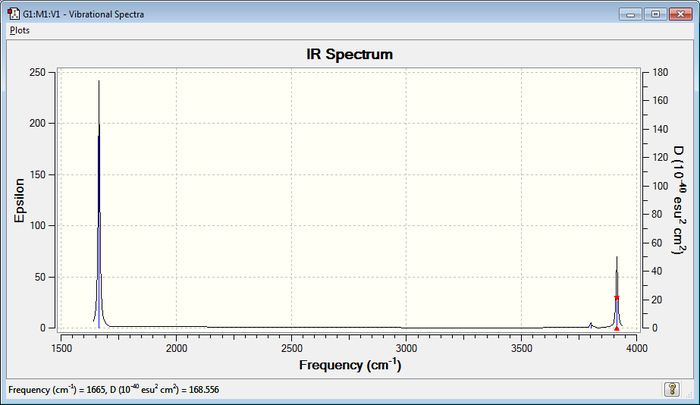

Mode 1 is a "bending" vibration, mode 2 is symmetrical "stretching" and mode 3 is asymmetrical "stretching".

The 3N-6 rule predicts 3 modes for the molecule being analyzed: 3(3) - 6 = 3.

In the spectrum it is possible to observe 2 bands of high intensity that correspond to the asymmetrical "stretching" and "bending" modes, which involve a significant change in dipole. In addition, there is a very small band given by the symmetrical "stretching" mode, which only involves a very little change in dipole.

IR Spectrum

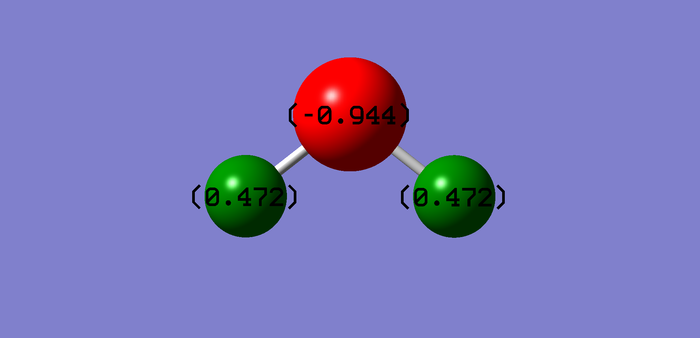

Charge analysis

Charge O-atom = (-0.944)

Charge H-atoms = (0.472)

Charges calculated by computational methods are as expected: in fact, O has a negative charge because is more electronegative than H, which instead presents a positive charge.

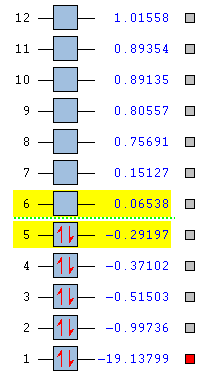

Molecular orbitals (MOs)

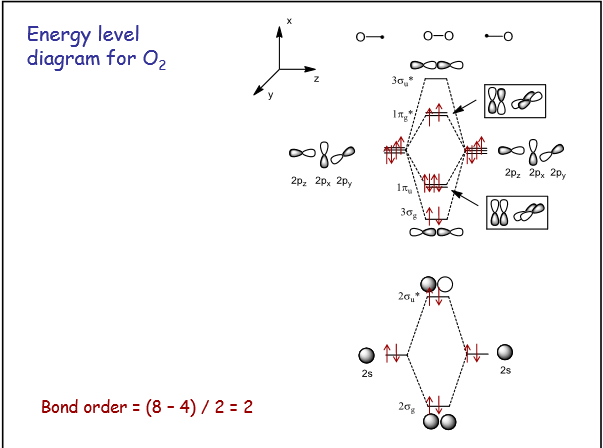

Energy level MO diagram

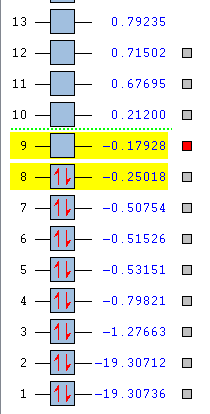

In this section, MOs of water are going to be analysed. The focus will be on lower energy orbitals because the prediction of their energies and shapes is far more accurate than it is with higher orbitals. This is the reason why the list showed in Figure 17 only includes the first 12 orbitals.

Figures 18 and 19 are the MO energy level diagrams for H2O. Since water is a polynuclear molecule, it is necessary to consider on one side the Atomic Orbitals (AOs) of Oxygen, and on the other side the Ligand Group Orbitals (LGOs), which are derived from the combination of the ligand's (Hydrogens) AOs [in-phase (σ) and out-of-phase(σ*)].

MO energy level diagrams are crucial in the understanding of Molecular Orbitals because they show how energies, shapes and phases of AOs combine and form MOs: in fact, the properties of the Molecular Orbitals depend on these factors.

The electronic configuration for Oxygen is 1s22s22p4, while the one for Hydrogen is 1s1. The valence orbitals are the 2s and 2p ones for Oxygen and 1s for the Hydrogens. Oxygen AOs are lower in energy than the 1s orbital in Hydrogen because Oxygen is more electronegative.

Analysis of bonding and antibonding Molecular Orbitals

It is important to highlight the fact that the Oxygen orbitals have a higher contribution in the formation of bonding MOs because Oxygen atom is much more electronegative than Hydrogen. At the same time however, the orbitals of the Hydrogens have a higher contribution in the formation of antibondig MOs.

The coordinates x, y and z will be the same as the one used in Figure 18.

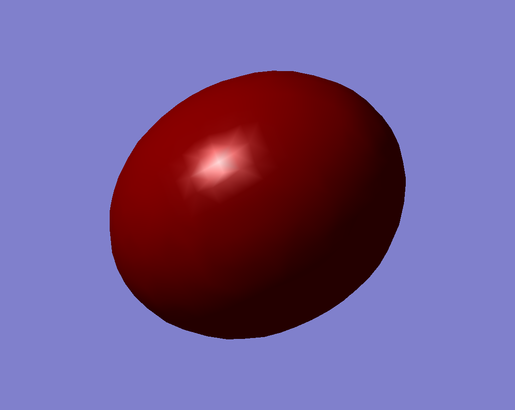

The orbital which is deepest in energy is the 1s Atomic Orbital of Oxygen: in fact, it does not contribute to the bonds of the molecule because it is too low in energy to interact with the other orbitals (#1 in Figure 17).

The MO shown in the following picture (#2 in Figure 17) is the bonding orbital with the lowest energy and it is given by the combination of the Oxygen 2s AO and the LGO's σ MO. As it is possible to observe from the Figure 18, this MO is also given by a small contribution of the Oxygen 2pz orbital, which strengthens the bond by lowering the orbital's energy.

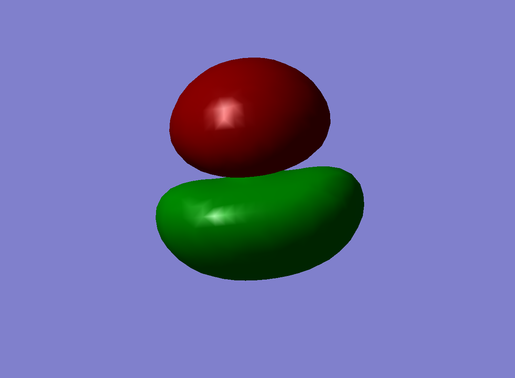

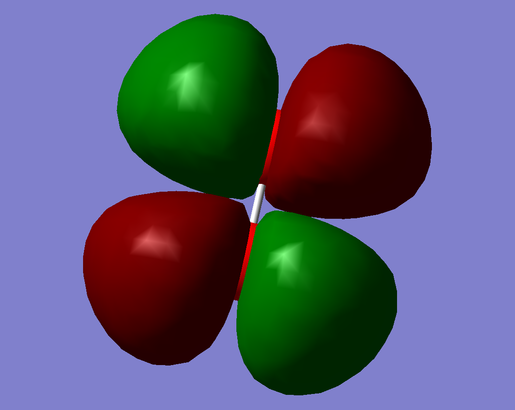

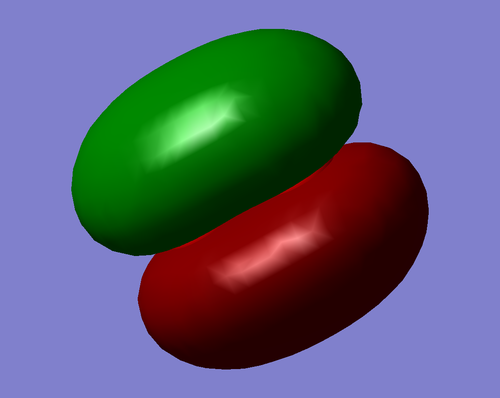

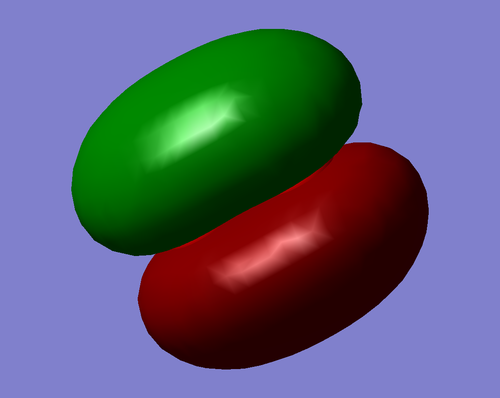

In Figure 22 it is possible to observe the bonding MO (#3 in Figure 17) generated from the mixing of the 2py Atomic Orbital and the Hydrogen σ MO. On the other hand, Figure 23 shows the corresponding antibonding MO (#7 in Figure 17) which is instead given by the interaction of the Oxygen 2py orbital with the Hydrogen σ* MO.

|

|

| Figure 22. Bonding MO orbital (given by 2py and H σ MO,1b2 in MO diagram). | Figure 23. Antibonding MO orbital (given by 2py and H σ* MO, 2b2 in MO diagram). |

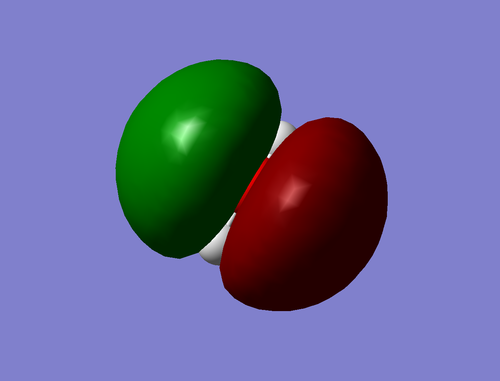

Figure 24 shows a bonding MO (#4 in Figure 17)given by the mixing of 2pz and H σ MO with a small contribution of the Oxygen 2s orbital (as shown in the diagram in Figure 18).

The Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (#6 in Figure 17) is instead an antibonding orbital which is given by the combination of the Hydrogen σ MO and again mixing between Oxygen 2pz and 2s AOs.

|

|

| Figure 24. Bonding MO orbital(3a1 in MO diagram). | Figure 25. Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO)- antibonding (4a1 in MO diagram). |

The Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (#5 in Figure 17) is just the Oxygen 2px orbital which does not combine with the 1s orbitals of the hydrogens. It is a non-bonding orbital and it is perpendicular to the molecular plane.

An analysis of the above discussed orbitals evidences how the electron density of the orbitals lower in energy is located more where the O-H bonds are, while the two higher energy orbitals (the bonding and the non-bonding ones, Figures 24 and 26) present an electron density that tends to be more "outside" the molecule. It is therefore likely that the electrons in the lower energy MOs are the ones that contribute to the O-H bonds, while the ones in the higher energy MOs are the ones that are commonly called lone pairs.

O2 Molecule

Key information

Dynamic image of the molecule

Figure 27. 3D representation of O2 molecule |

Optimisation data

Table 9. Important information about the optimisation process and the optimised molecule.

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| E(RB3LYP) | -150.25742434 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00007502 a.u. |

| Point Group | D*H |

| Optimised O-O Bond Distance | 1.21602 Angstroms |

Table 10. "Item" table, taken from the optimisation file produced by Gaussian and used to check that the optimisation has run properly (all the forces have to converge, maximum force on any atom should not exceed 0.00045 au, and the average (RMS) force should not exceed 0.0003 au).

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000130 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000130 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000080 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000113 0.001200 YES

You can find the optimisation file here.

Molecular vibrations

IR Spectrum

The analysis of the vibrations in this molecule shows that they do not cause any change in dipole and they are therefore IR inactive (no bands seen on the spectrum).

Molecular orbitals (MOs)

Energy level MO diagram

Analysis of bonding and antibonding Molecular Orbitals

|

|

| Figure 32. Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (Antibonding). | Figure 33. Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (Antibonding). |

|

|

|

| Figure 34. Bonding MO (sigma) - #3 in Figure 31. | Figure 35. Bonding MO (pi) - #6 in Figure 31. | Figure 36. Bonding MO (pi) - #7 in Figure 31. |

References

This report was written following the indications reported in the Computational Chemistry Lab Manual, which is accessible at Hunt Research Group website (URL: http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/year1_lab_start.html)

Background knowledge about Molecular Orbitals Theory is taken from Handouts 4 and 5 of Professor Vilar's Molecular Structure course.