Rep:Mod:fkl114318

Experiment 1C: Advanced Molecular Modelling and Assignment of the Absolute Configuration of an Epoxide

General Introduction to Molecular Mechanics

Introduction to MMFF94/MMFF94s

With advance in the development of computer hardware which leads to increased processing power and speed, molecular dynamics /mechanics continues to contribute to the development in computational chemistry. This is highlighted by the news that the most recent Chemistry Nobel Prize was awarded jointly to Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt and Arieh Warshel in 2013 for their contribution in computer simulation to understand complex chemical systems. More methods of molecular mechanics are being devised and improved by researchers so that the characteristic of a property of the molecule such as energy can be calculated in a more accurate way compared to the ‘true’ value.

Among the molecular properties a molecular mechanics force field can predict include the molecular geometries, conformational and stereoisomeric energies, torsional energies, intermolecular-interaction geometries and energies, vibrational frequencies and enthalpy of formation. Molecular-mechanics force fields or steric energies can be traced back to the work of Hendrickson in the 1960s. Since then, more variations have been developed such as MM1, MM2 and MM3 by Allinger and colleagues, CHARMM by Karplus and colleagues, AMBER by Kollman and coworkers and more. MMFF94, the initial version of MMFF (Merck Molecular Force Field) was developed by Thomas Halgren and his colleagues in Merck Research Laboratories followed by the MMFF94s, the ‘static’ (s) variant of MMFF94s. One of the main advantages of using MMFF94 over previous methods is that higher accuracy of molecular properties can be calculated. This is due to the fact that the core portion of MMFF94 has been derived from high-quality computational data.[1] [2]

MMFF94s was developed for use in energy-minimisation studies rather than MMFF94 which is used in molecular dynamics simulations. MMFF94 and MMFF94s share the same parameters and produce identical results in cases not involving delocalised trigonal nitrogen of amides or unsaturated amides. However, the major difference between these two variants is that MMFF94 normally produces optimised geometries that are puckered at such nitrogen centres whereas MMFF94s uses altered out of plane bending parameters in yielding planar or more nearly planar geometries seen in crystalline form. [1] [2]

The MMFF94 energy expression is represented by sum of few terms shown below:

EMMFF = EBS + EAB + ESB + EOOP + ETI + EVDW + EEI

Where EMMFF is the total energy calculated by using MMFF method, EBS is the bond stretching energy, EAB is the angle bending energy, ESB is the stretch-bend interaction, EOOP is the out-of-plane bending energy at tricoordinate centres, ETI is the torsion interactions, EVDW is the Van der Waals interactions and EEI is the electrostatic interactions. [1]

Part 1: Conformational Analysis Using Molecular Mechanics

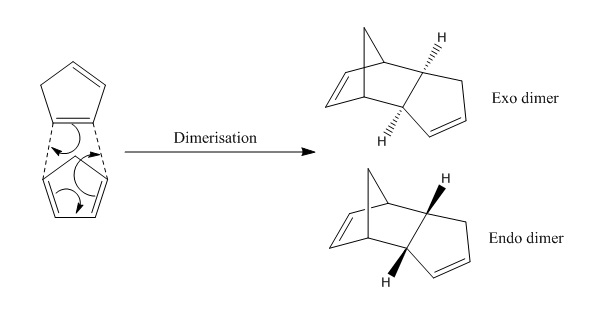

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene can dimerise to form either the exo or endo dimer. Experimentally, only the endo product is being observed as the product in thermal reaction. [3] The results calculated using MMFF94s for the energies of both endo and exo dimers shown below indicate that the exo dimer is more thermodynamically stable than endo dimer since it has a lower steric energy. The endo dimer has a greater steric energy than exo dimer due to the greater EAB where the difference may corresponds to the steric repulsion between the two fused cyclopentene rings in arc-like shape. However, in the dimerization of cyclopentadiene (a Diels-Alder reaction), the endo dimer is the sole product formed due to its stabilised transition state compared to the exo dimer. This can be explained by the presence of stabilising secondary orbital interaction in the endo transition state that the exo adduct does not have. Hence, the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is kinetically controlled where the kinetic product is endo dimer.

| Energies / kcal mol-1 | ||||||||

| EMMFF | EBS | EAB | ESB | EOOP | ETI | EVDW | EEI | |

| Endo dimer | 58.256 | 3.464 | 33.204 | -2.072 | 0.0217 | -3.006 | 12.406 | 14.238 |

| Exo dimer | 55.419 | 3.540 | 30.810 | -2.045 | 0.0168 | -2.656 | 12.741 | 13.012 |

| Endo and Exo Transition State | Structure of Endo Dimer | Structure of Exo Dimer | ||||||

|

|

|

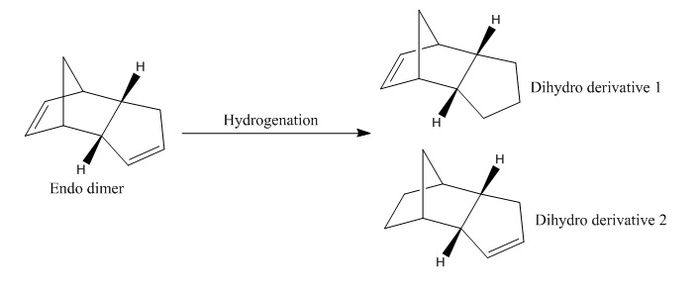

The Hydrogenation of Dicyclopentadiene

The endo dicyclopentadiene can undergo hydrogenation to produce initially one of the dihydro derivatives 1 and 2. The energies of both derivatives are calculated using MMFF94s method and the results are shown below. Derivative 2 has less steric energy than 1 which indicates that derivative 2 should be the thermodynamic product. This prediction is indeed correct with the literature where the first step of hydrogenation takes place in the norbornene part of the molecule, followed by the second C-C double bond in the molecule. The reaction heat of reaction of the two steps is -138.8 kJ mol-1 and -109.5 kJ mol-1 respectively. A tetrahydro derivative is produced at the end of the reaction after prolonged hydrogenation.[4] Overall, the hydrogenation of endo dicyclopentadiene is thermodynamically controlled.

| Energies / kcal mol-1 | ||||||||

| EMMFF | EBS | EAB | ESB | EOOP | ETI | EVDW | EEI | |

| Dihydro derivative 1 | 48.677 | 3.372 | 29.074 | -2.088 | 0.0154 | -0.304 | 13.494 | 5.114 |

| Dihydro derivative 2 | 38.314 | 2.930 | 21.093 | -1.709 | 0.00048 | 0.165 | 10.686 | 5.149 |

Atropisomerism in an Intermediate Related to the Synthesis of Taxol

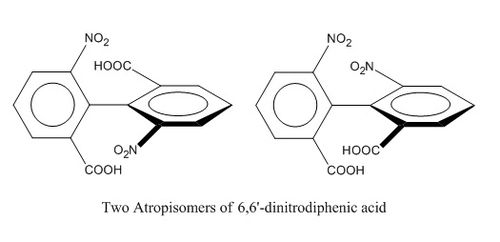

Atropisomerism is a type of stereoisomerism in a system where free rotation about a single covalent bond is obstructed sufficiently that different stereoisomers can be isolated. [5] One classic example that demonstrates the concept of atropisomerism is shown below [6]:

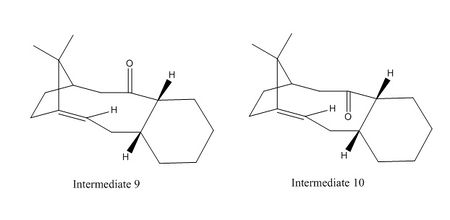

In the total synthesis of Taxol, one of the key intermediates exhibits atropisomerism. Intermediate 9 or 10 shown below has the carbonyl group pointing either up or down on standing where the compound isomerises to the alternative carbonyl isomer.

| Structures of Molecule 9 & 10 | 3D View of Intermediate 9 | 3D View of Intermediate 10 | ||||||

|

|

|

MMFF94s force-field is once again used to determine and compare the steric energies of these two intermediates. Based on the results shown below, intermediate 10 has a lower steric energy than 9 suggesting it is a more stable conformation than that of 9. The main difference in energies of the two atropisomers is EAB (difference of 5.651 kcal mol-1) which is related to the strain energy of the larger ring in the molecule. From EAB, we can infer that the carbonyl group in intermediate 10 which heads down causes a smaller twisting around the C-C double bond in the molecule; this maintains the HOMO-LUMO difference. Less twisted bridgehead olefins then have less diradicaloid character and reduced reactivity. Therefore, the alkene in intermediate 10 reacts abnormally slow. [7]

| Energies / kcal mol-1 | ||||||||

| EMMFF | EBS | EAB | ESB | EOOP | ETI | EVDW | EEI | |

| Intermediate 9 | 70.967 | 7.628 | 28.487 | -0.0776 | 1.006 | 0.813 | 32.783 | 0.327 |

| Intermediate 10 | 67.528 | 8.123 | 22.836 | 0.0970 | 1.055 | 2.083 | 33.363 | -0.0297 |

Part 1: Spectroscopic Simulation Using Quantum Mechanics

Spectroscopy of an Intermediate Related to the Synthesis of Taxol

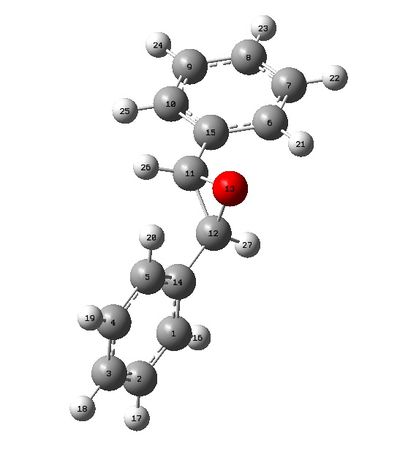

| Structures of Molecule 17 & 18 | 3D View of Molecule 17 | 3D View of Molecule 18 | ||||||

|

|

|

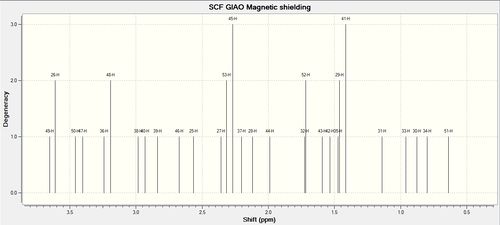

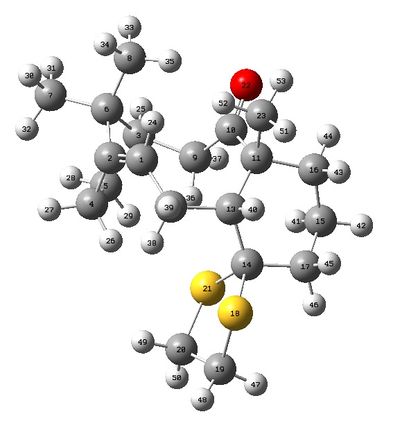

Molecules 17 and 18 are derivatives of intermediate 9 and 10 shown above. To calculate the NMR spectra of molecules 17 and 18, MMFF94s is used in the first stage of optimising the molecules followed by using Gaussian to reach the aim mentioned earlier. The results obtained are compared with literature values to determine the accuracy of the predictions.[8]

NMR Spectra of Intermediate 17

Calculations of NMR spectra of molecule 17 can be found here: DOI:10042/27141

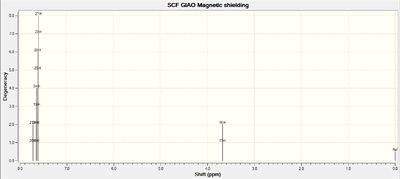

1H NMR Spectrum of Molecule 17

| 1H NMR Spectrum of Molecule 17 (Full) | 1H NMR Spectrum of Molecule 17 (Zoom in) |

|

|

| H-Atoms | Chemical Shift / ppm | Integration Height (Degeneracy) | Literature Values | Molecule 17 with Labeled Atoms |

| 24 | 5.9940 | 1 | 4.84 |  |

| 49 | 3.6523 | 2 | 3.40-3.10 | |

| 26 | 3.6110 | 2 | 3.40-3.10 | |

| 50 | 3.4571 | 1 | 3.40-3.10 | |

| 47 | 3.4030 | 1 | 3.40-3.10 | |

| 36 | 3.2422 | 2 | ||

| 48 | 3.1933 | 2 | ||

| 38 | 2.9846 | 1 | 2.99 | |

| 40 | 2.9305 | 1 | ||

| 39 | 2.8380 | 1 | ||

| 46 | 2.6730 | 1 | Remarks | |

| 25 | 2.5654 | 1 | In general, the prediction of 1H NMR spectrum agrees fairly with the literature values [8] but some of the literature values cannot be correlated to the predicted values especially in the lower chemical shift region. | |

| 27 | 2.3569 | 3 | ||

| 53 | 2.3155 | 3 | ||

| 45 | 2.2700 | 3 | ||

| 37 | 2.2025 | 1 | ||

| 28 | 2.1193 | 1 | ||

| 44 | 1.9882 | 1 | ||

| 32 | 1.7267 | 2 | ||

| 52 | 1.7176 | 2 | ||

| 43 | 1.5932 | 1 | ||

| 42 | 1.5337 | 1 | ||

| 35 | 1.4727 | 3 | 1.38 | |

| 29 | 1.4617 | 3 | 1.38 | |

| 41 | 1.4158 | 3 | 1.38 | |

| 31 | 1.1415 | 1 | ||

| 33 | 0.9600 | 1 | ||

| 30 | 0.8777 | 1 | ||

| 34 | 0.8001 | 1 | ||

| 51 | 0.6382 | 1 |

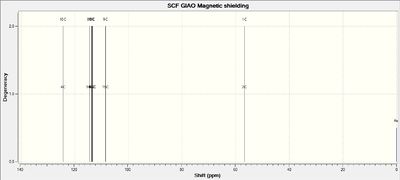

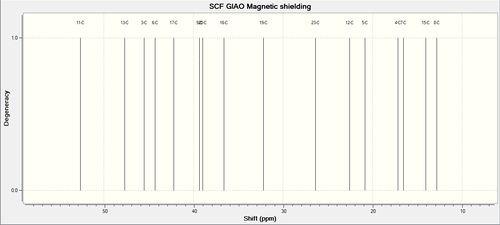

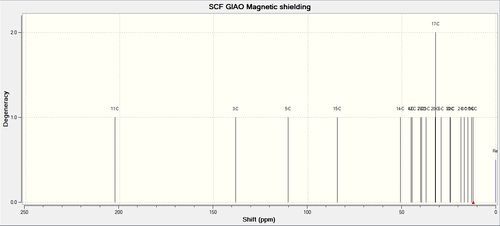

13C NMR Spectrum of Molecule 17

| 13C NMR Spectrum of Molecule 17 (Full) | 13C NMR Spectrum of Molecule 17 (Zoom in) |

|

|

| C-Atoms | Chemical Shift / ppm | Integration Height (Degeneracy) | Literature Values | Remarks |

| 10 | 210.42 | 1 | 218.79 | In general, the prediction of 13C NMR spectrum by calculation tends to be accurate in higher chemical shift region from about 32 ppm onwards when compared with literature values [8]. |

| 2 | 139.99 | 1 | 144.63 | |

| 1 | 107.25 | 1 | 125.33 | |

| 14 | 83.283 | 1 | 72.88 | |

| 11 | 52.601 | 1 | 56.19 | |

| 13 | 47.650 | 1 | 52.52 | |

| 3 | 45.496 | 1 | 48.50 | |

| 6 | 44.262 | 1 | 46.80 | |

| 17 | 42.199 | 1 | 45.76 | |

| 9 | 39.328 | 1 | 39.80 | |

| 20 | 38.951 | 1 | 38.81 | |

| 16 | 36.580 | 1 | 35.85 | |

| 19 | 32.167 | 1 | 32.66 | |

| 23 | 26.378 | 1 | 28.79 | |

| 12 | 22.549 | 1 | 28.29 | |

| 5 | 20.859 | 1 | 26.88 | |

| 4 | 17.154 | 1 | 25.66 | |

| 7 | 16.549 | 1 | 23.86 | |

| 15 | 14.053 | 1 | 20.96 | |

| 8 | 12.820 | 1 | 18.71 |

NMR Spectra of Intermediate 18

Calculations of NMR spectra of molecule 18 can be found here: DOI:10042/27140

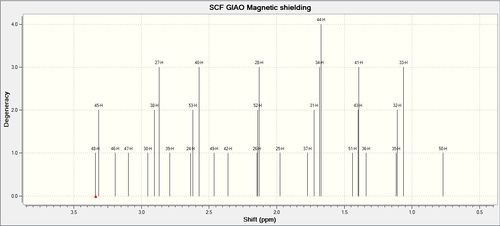

1H NMR Spectrum of Molecule 18

| 1H NMR Spectrum of Molecule 18 (Full) | 1H NMR Spectrum of Molecule 18 (Zoom in) |

|

|

| H-Atoms | Chemical Shift / ppm | Integration Height (Degeneracy) | Literature Values | Molecule 18 with Labeled Atoms |

| 29 | 6.1108 | 1 | 5.21 |  |

| 48 | 3.3395 | 2 | ||

| 45 | 3.3167 | 2 | ||

| 46 | 3.1941 | 1 | 2.70-3.00 | |

| 47 | 3.0975 | 1 | 2.70-3.00 | |

| 30 | 2.9532 | 3 | 2.70-3.00 | |

| 38 | 2.9035 | 3 | 2.70-3.00 | |

| 27 | 2.8701 | 3 | 2.70-3.00 | |

| 39 | 2.7907 | 1 | 2.70-3.00 | |

| 24 | 2.6362 | 3 | ||

| 53 | 2.6214 | 3 | Remarks | |

| 40 | 2.5756 | 3 | In general, the prediction of 1H NMR spectrum fairly agrees with the literature values [8] with some of the literature values cannot be correlated to the predicted values. | |

| 49 | 2.4644 | 1 | ||

| 42 | 2.3597 | 1 | ||

| 26 | 2.1455 | 3 | ||

| 52 | 2.1396 | 3 | ||

| 28 | 2.1310 | 3 | ||

| 25 | 1.9744 | 1 | ||

| 37 | 1.7719 | 4 | ||

| 31 | 1.7239 | 4 | ||

| 34 | 1.6828 | 4 | ||

| 44 | 1.6726 | 4 | ||

| 51 | 1.4393 | 3 | 1.50-1.20 | |

| 43 | 1.3980 | 3 | 1.50-1.20 | |

| 41 | 1.3945 | 3 | 1.50-1.20 | |

| 36 | 1.3405 | 1 | ||

| 35 | 1.1178 | 3 | 1.03 | |

| 32 | 1.1087 | 3 | 1.03 | |

| 33 | 1.0627 | 3 | 1.03 | |

| 50 | 0.7706 | 1 |

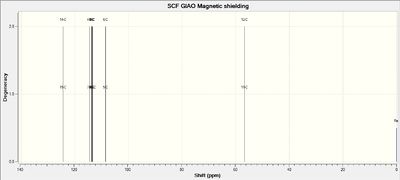

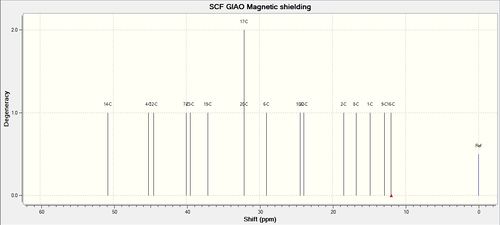

13C NMR Spectrum of Molecule 18

| 13C NMR Spectrum of Molecule 18 (Full) | 13C NMR Spectrum of Molecule 18 (Zoom in) |

|

|

| C-Atoms | Chemical Shift / ppm | Integration Height (Degeneracy) | Literature Values | Remarks |

| 11 | 202.521 | 1 | 211.49 | In general, the prediction of 13C NMR spectrum does not really agree well with the literature values. [8]' The difference between the prediction and literature values ranges from about 3 to 10 ppm. This may due to the reason that the molecule may not be optimised well at first stage before further calculations are done. |

| 3 | 138.370 | 1 | 148.72 | |

| 5 | 110.436 | 1 | 120.90 | |

| 15 | 84.402 | 1 | 74.61 | |

| 14 | 50.719 | 1 | 60.53 | |

| 4 | 45.177 | 1 | 51.30 | |

| 12 | 44.492 | 1 | 50.94 | |

| 7 | 39.985 | 1 | 45.53 | |

| 23 | 39.432 | 1 | 43.28 | |

| 19 | 37.069 | 1 | 40.82 | |

| 20 | 32.110 | 2 | 38.73 | |

| 17 | 32.066 | 2 | 36.78 | |

| 6 | 29.032 | 1 | 35.47 | |

| 10 | 24.426 | 1 | 30.84 | |

| 22 | 23.944 | 1 | 30.00 | |

| 2 | 18.452 | 1 | 25.56 | |

| 8 | 16.756 | 1 | 25.35 | |

| 1 | 14.840 | 1 | 22.21 | |

| 9 | 12.916 | 1 | 21.39 | |

| 16 | 12.013 | 1 | 19.83 |

Part 2: Analysis of the Properties of the Synthesised Alkene Epoxides

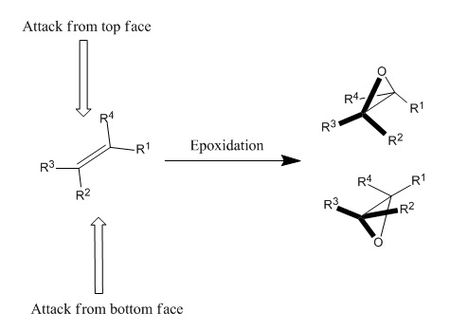

Epoxidation of olefins can potentially occur at the top or bottom face of the planar molecule which leads to the formation of products with different stereochemistry. This problem can be solved by using specific types of catalysts that leads to asymmetric epoxidation. In this case, only one of the two possible products with specific stereochemistry will be formed. The Shi asymmetric fructose catalyst and the Jacobsen asymmetric catalyst will be highlighted in the following section. The reactants used for asymmetric epoxidation are styrene and trans-stilbene where the configuration of the products from these two reactants are predicted and rationalised.

The Two Catalytic Systems

The Shi Asymmetric Fructose Catalyst

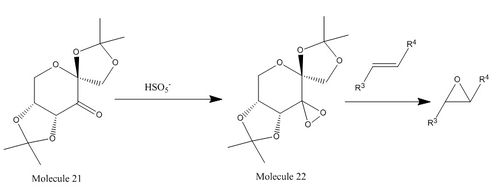

Studies show that molecule 21 is a very efficient catalyst for the epoxidation of trans- and trisubstituted olefins. Steric effect is the major explanation for the enantioselectivity in the epoxidation of alkenes by Shi catalyst. Based on the proposed competing transition states A and B shown above, spiro A is the major transition state as opposed to B since there is steric clash between the dimethyl ketal group of the catalyst and the substituent R1 on the olefin in B. [9] Molecule 21 is the stable precursor to the Shi catalyst and species 22 is the active catalyst under generation of persulfuric acid.

The Jacobsen Asymmetric Catalyst

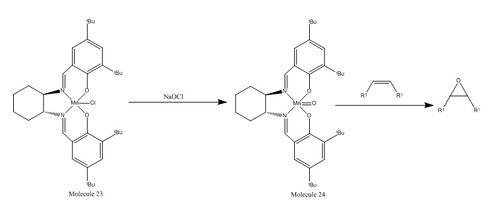

Simplified mechanism for the epoxidation of a cis-alkene by Jacobsen catalyst is shown above. The reaction proceeds through two sequential C-O bond forming steps. The first step is the addition of a cis-alkene to the (salen)-Mn(V) oxo species which generates a radical intermediate. The stereochemistry information of the alkene is lost once the radical species is formed since the C-Ar bond can then rotate before collapse to form a mixture of cis and trans epoxides.[10] Molecule 23 is the stable pre-catalyst and species 24 is the active catalyst generated from hypochlorite.

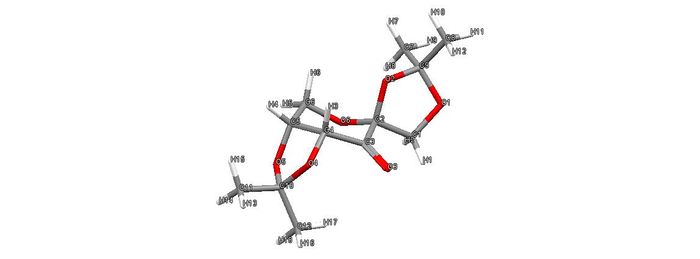

The Crystal Structures of the Catalysts

Molecule 21 (Precursor to the Shi Catalyst)

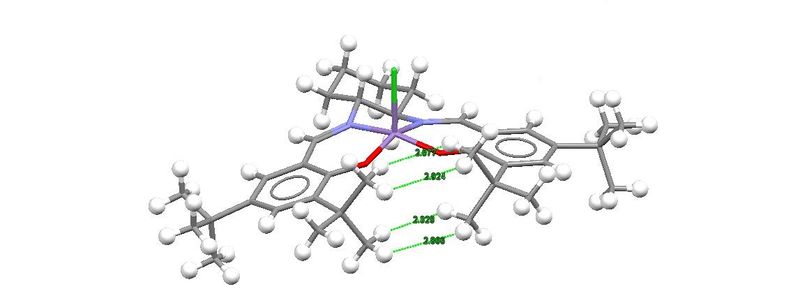

Molecule 23 (Precursor to the Jacobsen Catalyst)

The molecule adopts a nearly square pyramidal molecular geometry. The molecular is nearly planar due to delocalisation of electron density at both sides of the salen ligand. The two adjacent t-butyl groups on the two aromatic rings are close in distance to each other where the distance between the hydrogen atoms on the t-butyl groups are shown in the structure above. The interactions between these hydrogen atoms are not repulsive. This is because the distance between them is more than 2.1 Å which exceeds the sum of two hydrogen atoms Van der Waals radii which is 1.10 Å each. The maximum attraction occurs when the distance between two non-bonded hydrogen atoms is around 2.4 Å and this is seen in the crystal structure of molecule 23.[11] Therefore, we may safely deduce that the interaction between the hydrogen atoms of the two t-butyl groups on each side of the ring helps in stabilising the molecule.

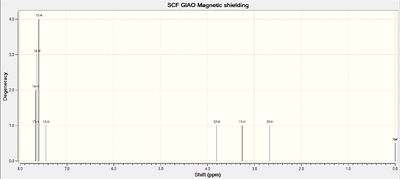

The calculated NMR Properties of Styrene and Stilbene Oxides

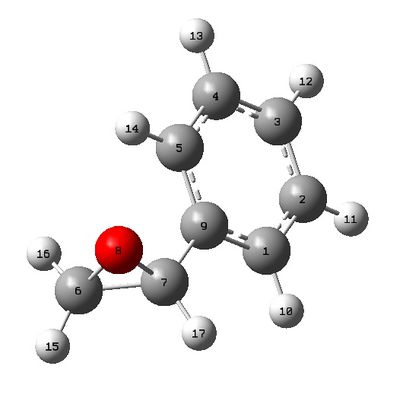

NMR Spectra of Styrene Oxide

Calculations of NMR spectra of (R) and (S)-styrene oxide can be found here: DOI:10042/27142 and DOI:10042/27143 respectively.

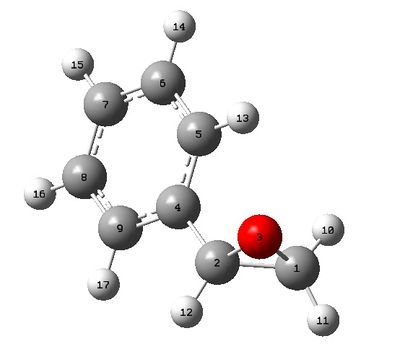

NMR Spectra of Stilbene Oxide

Calculations of NMR spectra of (R,R) and (S,S)-stilbene oxide can be found here: DOI:10042/27145 and DOI:10042/27144 respectively.

Assignment of Absolute Configuration of the Products

The Calculated Chiroptical Properties of Products

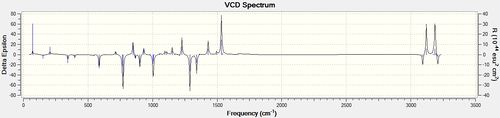

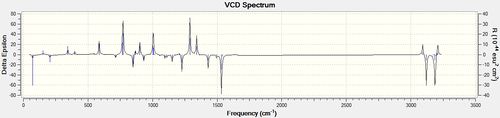

The optical rotatory power (ORP) and vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) calculated for the products are compared with literature values.

Chiroptical Properties of Styrene Oxide

Calculations of ORP values of (R) and (S)-styrene oxide can be found here: DOI:10042/27146 and DOI:10042/27147 respectively.

In the case of (R)-styrene oxide, the predicted ORP differ from the literature value [12] by about 7 deg. The predicted ORP of (S)-styrene oxide differ from the literature value [13] by 1.53 deg suggesting a better prediction has been done compared to that of (R)-styrene oxide. However, the predicted ORP values for both molecules are almost identical but in opposite signs.

Chiroptical Properties of Stilbene Oxide

Calculations of ORP values of (R,R) and (S,S)-stilbene oxide can be found here: DOI:10042/27149 and DOI:10042/27150 respectively.

The predicted ORP of (R,R)-stilbene oxide is consistent with the literature value [14] which indicates the calculation done by Gaussian is quite accurate. On the other hand, the literature value of ORP [15] differs from the calculated ORP of (S,S)-stilbene oxide by 92.99 deg. This may due to the difference in experimental conditions in reality and calculation considered by Gaussian.

Usage of the (calculated) Properties of Transition State for the Reaction

Enantiomeric excess of one product over another can be calculated from the free energy difference between two diastereomeric transition states. This is done by using Curtin-Hammett principle which states that the relative amounts of product formed from two specific conformations are only depend on the difference in free energy of the transition states, provided the rates of reaction are slower than the rates of conformational interconversion.[16]

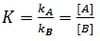

First the rate constant of a reaction is defined as:

Consider two enantiomers A and B can interconvert into each other, the rate constant also can be defined as the ratio between rate of formation of enantiomers A and that of B. This is also equals to the ratio of their concentrations:

According to Curtin-Hammett principle, because equilibration is rapid compared to the rates of conformational interconversion, the ratio of their concentrations remains constant and K is also constant. The product ratio can therefore be written as:

Where - ΔGTS is the difference in Gibbs free energy of the two transition states leading to enantiomers A and B.

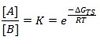

Enantiomeric excess is defined as:

Where XA and XB is mole fractions of products A and B respectively.

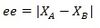

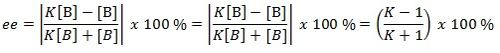

The term is usually expressed in percentage form and can be determined in alternative way if we know the amount of each enantiomer produced:

Since [A] = K[B] , this is substituted into the equation above which leads to:

The final equation obtained above is used to calculate the enantiomeric excess of one product over another and the results are shown below. Note that β-methyl styrene is the reactant for undergoing epoxidation by both Shi catalyst and Jacobsen catalyst.

For Shi Catalyst

| Free Energy of Transition State for (R,R)-Trans-β-methyl Styrene Oxide Formation | Free Energy of Transition State for (S,S)-Trans-β-methyl Styrene Oxide Formation | Difference in Free Energy Between Two Diastereomeric Transition States / Hartree | K (the ratio of concentrations of the two species based on free energy difference) | Enantiomeric Excess / % |

| -1343.022970 | -1343.017942 | -0.005028 | 4.8667 x 10-3 | 99.03 |

| -1343.019233 | -1343.015603 | -0.003630 | 2.1393 x 10-2 | 95.81 |

| -1343.029272 | -1343.023766 | -0.005506 | 2.9333 x 10-3 | 99.41 |

| -1343.032443 | -1343.024742 | -0.007701 | 2.8689 x 10-4 | 99.94 |

Note that the unit of difference in free energy between the two diastereomeric transtion states (in Hartree)is to be converted to units in J mol-1 in order to calculate values of enantiomeric excess correctly. Also the temperature used in calculation has been taken as 298.15 K and 1 Hatree is equal to 4.359 7 × 10−18 J.

Based on the calculations shown above, (R,R)-Trans- β –methyl styrene oxide is the sole product from epoxidation with enantiomeric excess ranging from 95-99 %. The prediction is indeed accurate when compared with literature where at 30°C, 91.1 % of (R,R) products over (S,S) product was obtained. [17]

For Jacobsen Catalyst

| Free Energy of Transition State for (S,R)-Cis-β-methyl Styrene Oxide Formation | Free Energy of Transition State for (R,S)-Cis-β-methyl Styrene Oxide Formation | Free Energy Difference Between Two Diastereomeric Transition States / Hartree | K (the ratio of concentrations of the two species based on free energy difference) | Enantiomeric Excess / % |

| -3383.259559 | -3383.251060 | -0.008499 | 1.2321 x 10-4 | 99.97 |

| -3383.253442 | -3383.250270 | -0.003172 | 3.4750 x 10-2 | 93.28 |

| Free Energy of Transition State for (S,S)-Trans-β-methyl Styrene Oxide Formation | Free Energy of Transition State for (R,R)-Trans-β-methyl Styrene Oxide Formation | Free Energy Difference Between Two Diastereomeric Transition States / Hartree | K (the ratio of concentrations of the two species based on free energy difference) | Enantiomeric Excess / % |

| -3383.262481 | -3383.253816 | -0.008665 | 1.0335 x 10-4 | 99.98 |

| -3383.257847 | -3383.254344 | -0.003503 | 2.4474 x 10-2 | 95.22 |

Based on the calculations above, (S,R)-Cis-β-methyl Styrene Oxide is the sole product from epoxidation by Jacobsen catalyst which agrees well with literature (enentiomeric excess of 88 %) [18]

Investigation of Interactions at the Active Site of Reaction Transition State

Shi Fructose Catalyst

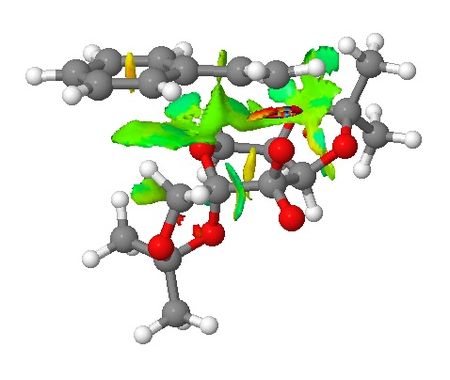

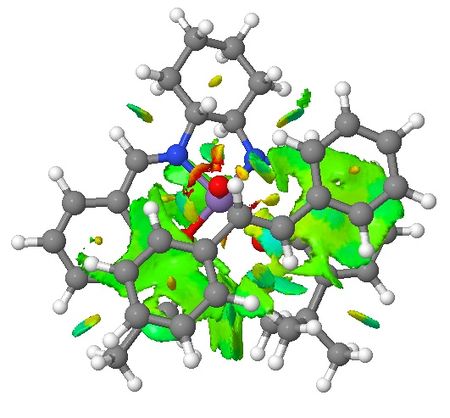

Transiton states of Shi epoxidation of styrene are presented in this section where their non-covalent interactions (NCI) and electronic topology (QTAIM) are investigated. The styrene molecule will approach the catalyst in a way to avoid steric repulsion with the two 5-membered rings attached to the 6-membered ring where the site is the active site. This concept has been enforced in the section of introduction to Shi asymmetric fructose catalyst. NCI are viewed from the side of the transition state (TS) and from the top where the styrene molecule approaches the catalyst. Based on NCI shown below for both TSs, it is clear there is more NCI for (R)-styrene oxide formation TS than that of (S)-styrene oxide (larger green area around the active site of the catalyst). It can be seen that the main difference in NCI for both TSs is that in (R)-styrene oxide TS, the aromatic ring of styrene interacts with the –CH2- below it which may lead to stabilisation of the TS.

| (R)-Styrene Oxide | (S)-Styrene Oxide | |||||||

| 3D View of Transition State of Shi Epoxidation |

|

| ||||||

| Non-covalent Interactions in the Transition State |   |

|

| (R)-Styrene Transition State | (S)-Styrene Transition State |

|

|

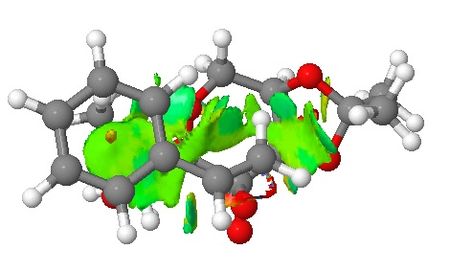

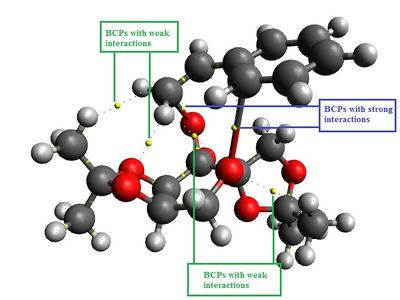

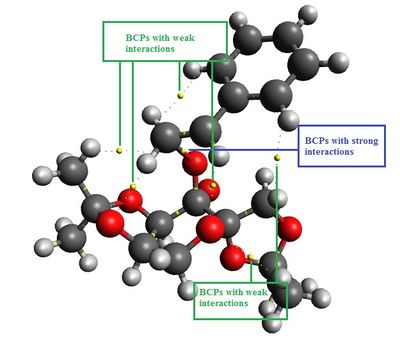

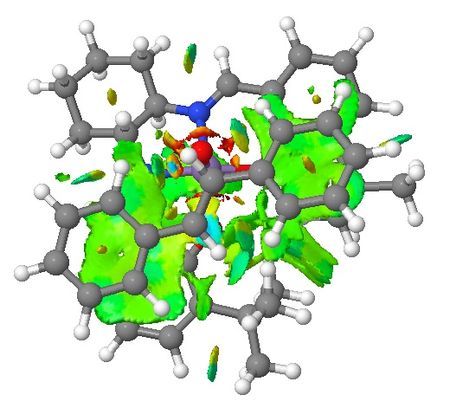

Based on the QTAIM analysis above, (S)-styrene TS has more bond critical points (BCPs) where interactions occur than that of (R)-styrene TS. However, it only has two more weak interactions but lack of a strong interaction as opposed to (R)-styrene TS. In (R)-styrene TS, there are two BCPs with strong interactions in the active site of catalyst where one of the oxygen atoms being transferred to the styrene molecule whilst another BCP indicating the oxygen atom in the 6-membered sing of the catalyst stabilising the aromatic ring of styrene. This does not occur in (S)-styrene where there are two weak interactions stabilise the aromatic ring. More calculations are needed to be done to quantify the interactions exist in both TSs so that valid comparisons can be made.

Jacobsen Catalyst

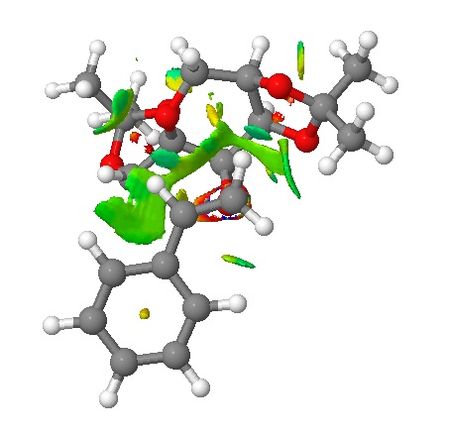

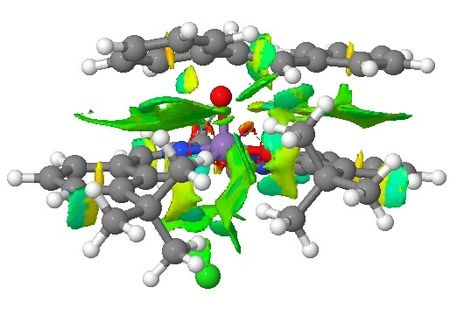

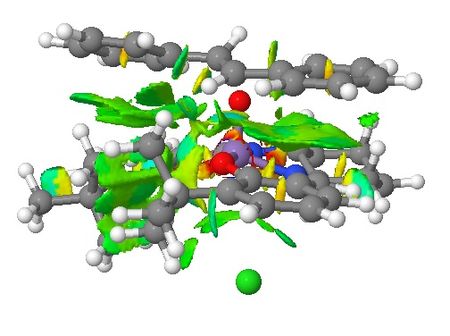

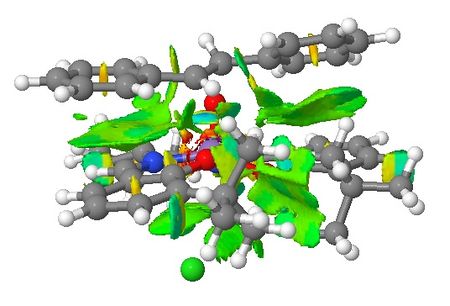

Transiton states of Jacobsen epoxidation of trans-stilbene are presented in this section where their non-covalent interactions (NCI) and electronic topology (QTAIM) are investigated. NCI are viewed from the sides and top of stilbene approaching the TS. Based on the NCI for both transition states, it seems that there are more favourable interactions in formation of (R,R)-stilbene oxide TS than in (S,S)-stilbene oxide. This is due to more favourable interactions between the phenyl rings of stilbene with the catalyst. There are favourable interactions between the two adjacent t-butyl groups on the two aromatic rings which supports the explanations in the section of discussion about the crystal structure of catalyst.

| (S,S)-Stilbene Oxide | (R,R)-Stilbene Oxide | |||||||

| 3D View of Transition State of Jacobsen Epoxidation |

|

| ||||||

| Non-covalent Interactions in the Transition State |    |

|

| (S,S)-Stilbene Oxide Formation Transition State | (R,R)-Stilbene Oxide Formation Transition State |

|

|

Based on the QTAIM analysis above, there are numerous BCPs indicating strong and weak interactions exist in both transition states. There are strong interactions between the aromatic rings of stilbene and aromatic rings of salen ligand of the catalyst which helps to stabilise the transition state in the formation of (S,S)-stilbene oxide. There are also weak interactions between the two adjacent t-butyl groups on the two aromatic rings which again supports the explanations in the section of discussion of crystal structure of catalyst. These interactions are found in both of the TSs. One interesting phenomenon with (R,R)-stilbene oxide formation TS is that there are no interactions between one of the phenyl rings and the catalyst which somewhat contradicts with NCI of the system. Again, more calculations are needed to be done to quantify the interactions exist in both TSs so that valid comparisons can be made between these two TSs.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 T.Halgren, "Merck Molecular Force Field. I. Basis, Form, Scope, Parameterisation, and Performance of MMFF94", J. Comput. Chem., 1996, 17, 490-519.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 T.Halgren, "MMFF VI. MMFF94s Option for Energy Minimization Studies", J. Comput. Chem., 1999, 20, 720-729.

- ↑ A. Turnbull and H. Hull, "A Thermodynamic Study of the Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene", Aust. J. Chem., 1968, 21, 1789-1797.

- ↑ D. Skala and J. Hanika, "Kinetics of Dicyclopentadiene Hydrogenation Using Pd/C Catalyst", Pet. Coal, 2003, 45, 105-108.

- ↑ P. Lloyd-Williams and E. Giralt, "Atropisomerism, Biphenyls and the Suzuki Coupling- Peptide Antibiotics", Chem. Soc. Rev., 2001, 30, 145–157. DOI:10.1039/B001971M

- ↑ G. Christie and J. Kenner, "LXXI.—The molecular configurations of polynuclear aromatic compounds. Part I. The resolution of γ-6 : 6′-dinitro- and 4 : 6 : 4′ : 6′-tetranitro-diphenic acids into optically active components", J. Chem. Soc. Trans., 1922, 121, 614–620. DOI:10.1039/CT9222100614

- ↑ W. Maier and P. Schleyer, "Evaluation and Prediction of the Stability of Bridgehead Olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891-1900. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 L. Paquette, N. Pegg, D. Toops, G. Maynard and R. Rogers, "[3.3] Sigmatropy within 1-vinyl-2-alkenyl-7,7-dimethyl-exo-norbornan-2-ols. The first atropselective oxyanionic Cope rearrangement", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277–283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ O. A. Wong, B. Wang, M.-X. Zhao, and Y. Shi, "Asymmetric Epoxidation Catalyzed by α,α-Dimethylmorpholinone Ketone. Methyl Group Effect on Spiro and Planar Transition States", J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74, 6335-6338. DOI:10.1021/jo900739q

- ↑ M. Palucki, N. Finney, P. Pospisil, M. Güler, T. Ishida and E. Jacaobsen, "The Mechanistic Basis for Electronic Effects on Enantioselectivity in the (salen)Mn(III)-Catalyzed Epoxidation Reaction", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1998, 120, 948-954. DOI:10.1021/ja973468j

- ↑ M. Mantina, A. C. Chamberlin, R. Valero, C. J. Cramer, and D. G. Truhlar, "Consistent van der Waals Radii for the Whole Main Group", J. Phys. Chem. A, 2009, 113, 5806–12. DOI:10.1021/jp8111556

- ↑ D. E. White and E. N. Jacobsen, "New Oligomeric Catalyst for the Hydrolytic Kinetic Resolution of Terminal Epoxides Under Solvent-free Conditions", Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2003, 14, 3633–3638. DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2003.09.024

- ↑ H. Lin, J. Qiao, Y. Liu, and Z.-L. Wu, "Styrene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. LQ26 catalyzes the asymmetric epoxidation of both conjugated and unconjugated alkenes", , J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym., 2010, 67, 236–241. DOI:10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.08.012

- ↑ A. Solladié-Cavallo, A. Diep-Vohuule, V. Sunjic, and V. Vinkovic, "A Two-step Asymmetric Synthesis of Pure Trans-(R,R)-Diaryl-epoxides", Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 1996, 7, 1783–1788. DOI:10.1016/0957-4166(96)00213-3

- ↑ T. Niwa and M. Nakada, "A Non-Heme Iron(III) Complex with Porphyrin-like Properties That Catalyzes Asymmetric Epoxidation", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2012, 134, 13538–13541. DOI:10.1021/ja304219s

- ↑ J. Seeman, "The Curtin-Hammett principle and the Winstein-Holness equation: new definition and recent extensions to classical concepts", J. Chem. Educ., 1986, 63, 42–48. DOI:10.1021/ed063p42

- ↑ Z. Wang, Y. Tu, M. Frohn, J. Zhang and Y. Shi, "An Efficient Catalytic Asymmetric Epoxidation Method", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 11224-11235. DOI:10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ T. S. Reger and K. D. Janda, "Polymer-Supported (Salen)Mn Catalysts for Asymmetric Epoxidation: A Comparison between Soluble and Insoluble Matrices", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2000, 122, 6929–6934. DOI:10.1021/ja000692r