Rep:Mod:fht14ts

Computational Investigations of the Transition States of Pericylic Reactions

Introduction

This work covers the usage of computational methods to investigate the transition structures, approach trajectories, and thermodynamics of various pericyclic reactions. One can do this by computing the energy of an initial structure, perturbing the structure, and then computing the energy of the resulting structure. Iteratively performing this procedure allows one to map out the Potential Energy Surface (PES) for some reaction process. Evaluations of the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate, as well as molecular orbital discussion, have also been made for the investigated reactions.

Potential Energy Surfaces

It is irrelevant to most investigations to gain an idea of what the entire PES looks like, instead we search for certain useful topological features — namely minima, maxima, and saddle-points. A minimum is defined by being a point where the derivative in every direction is zero, and the second derivative in every direction is positive. A minimum therefore represents a structure that the system can relax into following some small perturbation. It follows that a maximum on the surface represents an unstable structure, having its first derivative be zero in every direction, and its second derivatives negative. As such any small perturbation will cause it to fall towards some other lower energy structure. Murrell and Lailer define a transition state as a point with a single negative Hessian eigenvalue, which we can visualise as a point which is a maximum in one direction, and a minimum in all others.[1] From these definitions we would expect that a transition structure would have a single negative imaginary frequency, corresponding to a vibration along the normal mode it has a maximum in, providing us with a useful method for verifying computed transition structures. Fig. 1 shows a 2D reaction profile, demonstrating the aforementioned topological features. It is noted that as this is a two dimensional case, the transition structure and maximum are the same point.

Nf710 (talk) 18:22, 22 February 2018 (UTC) Good understanding of the literature but you havent shown much understanding of what the 'directions' are. they are the degrees of freedom.

Investigation Protocol

For the following investigations in this report, GaussView (version 5.0.9) was used to interface with Gaussian 09W (version 9.5).[2,3] The general process for investigating a reaction's transition structure was as follows:

- The reactants are drawn separately, and optimised to a minimum using the semi-empirical PM6 method

- These optimised structures are then placed together in an arrangement resembling a guess of the transition state structure

- For bonds being formed over the course of the reaction, an initial separation distance of 2–2.2 Å is chosen

- Bond lengths (an in certain cases, bond angles) involved in the reaction are frozen using the Redundant Coordinate Editor

- This system is then optimised to a minimum using the semi-empirical PM6 method

- The resulting structure is then optimised (alongside a frequency calculation) to a transition structure, using the Berny Algorithm

- We check if the resulting structure is a transition state by checking if there is a single negative imaginary vibrational frequency

- An Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculation is then performed, again using the semi-empirical PM6 method

- The resulting IRC plot should have a gradient of zero at both the reactants and products, and moves to a maximum at the transition state

Where stated, the more precise Density Functional Theory B3LYP method was also used (using 6-31G(d) as its basis set). In such cases the structures were first optimised to the less computationally demanding PM6 level, before the more costly DFT method was applied.

Over the course of our investigation, the above methodology was applied to the following reactions: the [4+2]-Diels–Alder cycloaddition of butadiene and ethene, the exo- and endo-cycloadditions of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole, and the Diels–Alder and cheletropic cycloadditions of ortho-xylylene and SO2. For parts of these reactions, discussions of molecular orbitals and/or thermochemistry were also made. Pericyclic reactions made good investigations due to having concerted bond formations, meaning that only a single (and therefore easier to determine) transition state was expected.

PM6 and DFT-B3LYP Methods

PM6 is a semi-empirical method, relying on a large compendium of reference data and various approximations in order to provide a rapid method of investigating chemical systems. In investigations of complex systems it is often not enough to solely use this method, but it is widely used to find a jumping-off point for further more advanced computational methods. For this investigation the PM6 method did prove sufficient in finding and characterising transition structures, but we note the relative imprecision of the reported data from this method.[4]

A more computationally advanced method is found in the DFT B3LYP method. Density Functional Theory uses the spatially dependent electron density as its functional in order to make observations of the electronic structure of a molecular system. These results can then be used to evaluate the energies of systems — allowing structures to be optimised, and transition structures to be found. B3LYP refers to the density functional being used — the Becke3–Lee–Yang–Parr functional, an adaptation of the BLYP functional. Since its introduction, the B3LYP functional has become very widely used in DFT calculations, providing results in good agreement with experiment.[5] 6-31G(d) was used as the basis-set in these calculations. This Pople basis set uses six Gaussians to make up each core atomic orbital basis function, and composes the valence orbitals from two basis functions using three and one Gaussian function respectively.[6] This basis set has been shown to provide good results that correspond well with experimental results.[7]

Nf710 (talk) 18:56, 22 February 2018 (UTC) You have shown some good understanding here and have clearly done some extra reading. It would have been really nice if you could have complimented your discussion with some of the equations related to these methods/ basis sets.

Exercise 1: Reaction of Butadiene with Ethene

(Fv611 (talk) Very nice work and discussion overall in this exercise - well done!)

Here the [4+2] Diels–Alder cycloaddition of butadiene and ethene was investigated at the PM6 level. Discussions of the transition state, molecular orbitals, and bond lengths have also been made.

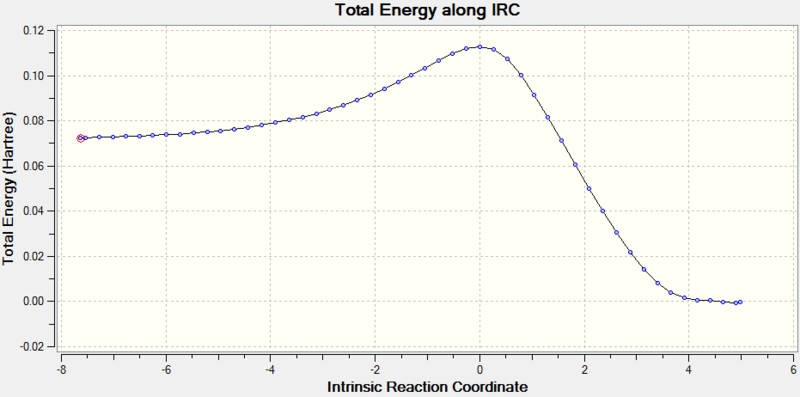

Investigation

The structures of butadiene and ethene were first optimised at the PM6 level. They were then placed into the same environment, with ethene approximately 2.2 Å away from the terminal ends of the diene, at an angle of approximately 100o to the carbon plane. This bond length was chosen to allow the ethene to be close enough for an interaction, but far away enough that bonding had not started to occur. The bond angle was chosen to resemble a general Bü–Dunitz angle (typically 90–110o). The bond lengths were then frozen, and the system optimised to a minimum at the PM6 level. The resulting system was then optimised to a transition state (using the Berny algorithm) at the PM6 level. The resulting system was found to have a vibrational mode at -949 cm-1. As previously described this presence of a single negative vibrational frequency verifies this structure as the transition state. To further verify this an IRC calculation was performed at the PM6 level, the results of which are shown in Fig. 3. Here it can be seen that the gradients approach zero at the products and reactants, with a clear maximum (the transition state). The product was then optimised to a minimum at the PM6 level.

Discussion of Bond Lengths

In Table 1 the bond lengths (as described in Fig. 5) are tabulated for the reactants, transition state, and product of this reaction. Here it can be seen that the double bonds a, c, and e lengthen from 1.33–1.34 to 1.38 Å as they move to the transition state, and then to 1.50–1.54 Å as they become single bonds in the final product. The opposite is true for the single bond b, which contracts from 1.47 to 1.41 Å, and then further to 1.34 Å. We compare these values to the carbon-carbon bond lengths seen in ethane and ethene (calculated by a DFT B3LYP optimisation) — 1.53 and 1.33 Å. These lengths demonstrate that at the transition state bonds a, b, c, and e are all at some intermediate bond length, somewhere in-between a typical carbon-carbon single and double bond. This can be equivalently discussed as a change in hybridisation, in the case of a, c, and e, from sp2 to sp3, and from sp3 to sp2 for b. Equally therefore the hybridisation at the transition state is some intermediate between the two.

The bonds d and f represent the newly forming carbon-carbon single bonds. At the transition state these are both the same length, 2.11 Å, demonstrating the symmetry in the transition structure, as well as the concerted nature of the bond-forming process. 3.4 Å represents the closest distance between non-bonding carbons (twice the van der Waals radius of 1.7 Å), which is significantly more than the bond lengths d and f at the transition state — demonstrating that these bonds have started to form at the transition state. Equally these bonds change in the same way at the same time, demonstrating the bond formation is synchronous, as expected for a pericyclic reaction.

Below is also included a Jmol applet demonstrating the vibrational mode corresponding the the bonding process, -949 cm-1. Again here the symmetry (and synchronicity) of the reaction can be seen.

| Bond | Reactants | Transition State | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | 1.34 Å | 1.38 Å | 1.50 Å |

| b | 1.47 Å | 1.41 Å | 1.34 Å |

| c | 1.34 Å | 1.38 Å | 1.50 Å |

| d | N/A | 2.11 Å | 1.54 Å |

| e | 1.33 Å | 1.38 Å | 1.54 Å |

| f | N/A | 2.11 Å | 1.54 Å |

-949 cm-1 bonding vibration

Discussion of Molecular Orbitals

Before considering the Gaussian-calculated molecular orbitals, an attempt at predicting the molecular orbital diagram for the butadiene+ethene transition state was made. Once the required calculations were performed, this diagram was filled in with the determined molecular orbitals, as well as their relevant energies. From this it was seen that only orbitals of the same symmetries interact to form new orbitals, i.e. an symmetric-symmetric or asymmetric-asymmetric interaction. This is justified by considering the integrals of odd and even functions, zero and non-zero respectively. When considering the overlap of two orbitals, when they have the same symmetry they multiply to form an even function, and when they have differing symmetries they form an odd function. Therefore the only way to gain a non-zero, and therefore constructive, overlap integral is for the orbitals to have the same symmetry. This rule is represented mathematically below:

Included below are interactive Jmol applets, allowing the HOMO and LUMO of PM6-optimised butadiene and ethene to be explored, as well as the molecular orbitals they combine to form in the transition state. (Fv611 (talk) You could have added labels on your TS MOs to match them to the diagram above.)

Butadiene MO's

Transition State MO's

Ethene MO's

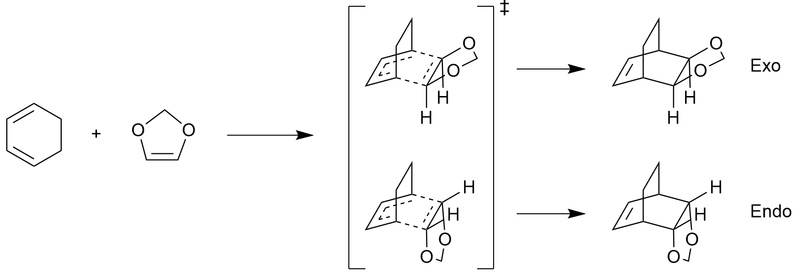

Exercise 2: Reactions of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

Here the two Diels–Alder cycloadditions of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole are investigated at the PM6 and B3LYP levels. Discussions of the transitions structures, molecular orbitals, secondary orbitals, and thermochemistries are also made.

Investigation

First the structures of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole were drawn, and then optimised to a minimum at the PM6 level. The resulting structures were then further optimised to a minimum at the B3LYP level. The optimised structures were then placed together in an arrangement resembling a guess at the transition structure for both the endo and exo reactions. Bonds involved in the reaction had their lengths frozen during an optimisation to a minimum at the B3LYP level. The resulting structures had their coordinates unfrozen, and optimisation + frequency calculations were performed on them to a transition state (using the Berny algorithm), first at the PM6 level, with those results then being run at the B3LYP level. The results at the PM6 level also had an IRC calculation (at the PM6 level), whereas the B3LYP results did not have an IRC calculation performed on them due to the extensive amount of computational time they would require. The endo and exo products were also drawn and optimised to a minimum at the PM6 and B3LYP levels.

Discussion of Transition State

The presence of a transition state was again verified by seeking out a single negative (imaginary) frequency vibration in a structure — corresponding to the bonding mode. In their final B3LYP transition state optimisations, the endo state has a single negative vibration at -529 cm-1, and the exo state has a single negative vibration at -521 cm-1. Both of these vibrational modes are displayed in the Jmol applets below.

Secondary verification of the transitions states were made by performing a PM6 IRC calculation on the PM6-optimised transition states (they were not performed on the B3LYP transition states so as to not mix methodologies). Both of these resulting plots correctly show that the gradient approaches zero at the reactants and products, as well as moving through a single transition state. These IRC plots are shown in the table below.

| Exo Transition State | End Transition State |

|

|

Discussion of Molecular Orbitals

The molecular orbital diagrams for these reactions closely resemble that of the previous exercise, having similarly constructed orbitals on its reactants. In contrast to the previous exercise, the relative energies of the frontier orbitals are now different. Due to the electron donating nature of the oxygens in 1,3-dioxole, the dieneophile is much more electron-rich than ethene. As such, the HOMO on 1,3-dioxole is closer in energy to the LUMO on cyclohexadiene than the HOMO on cyclohexadiene is to the LUMO on 1,3-dioxole. This relationship of energy levels allows this reaction to be termed the Inverse Electron-Demand Diels–Alder — contrasting the normal demand reaction in exercise 1.

Nf710 (talk) 19:30, 22 February 2018 (UTC) How do you know this? you have not investigated it?

The newly constructed molecular orbital diagrams of the endo and exo transition states are included below as Figs. 10 + 11. The HOMO and LUMO of 1,3-dioxole and cyclohexadiene are also included as interactive Jmol applets, alongside the four MOs they combine to form in the endo and exo transition structures.

(Fv611 (talk) You have computed your MO energies correctly, and reported them as such, but why did you not draw the MOs in order in your Endo diagram? For example, your TS LUMO+1 definitely has a lower energy than your diene's LUMO...)

|

|

1,3-Dioxole MO's

Cyclohexadiene MO's

Exo Transition State MO's

Endo Transition State MO's

Thermochemistry

Tabulated below are the calculated sums of electronic and thermal free energies for the B3LYP-optimised reactants, products, and transition structures. As well as this the barrier and reaction energies have also been calculated and are tabulated below. From these energies it can be seen that the endo product is ultimately the lowest in energy by 3.64 kJ/mol, making it the thermodynamic product. The kinetic product is defined as the product that is formed the fastest, so for this we must consider the Arrhenius relationship of rate of reaction: . This demonstrates the reaction with the lower barrier height will proceed the quickest. Here the exo product has the lower barrier (159.81 vs 167.64 kJ/mol), making the endo product the kinetic product as well. From evaluating the exponential it is predicted that the endo product forms approximately 2500 times faster.

| Species | Sum of free energies (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|

| Cyclohexadiene | -612593.065 |

| 1,3-Dioxole | -701188.620 |

| Reactants | -1313781.69 |

| Exo TS | -1313614.05 |

| Exo Product | -1313845.46 |

| Endo TS | -1313621.88 |

| Endo Product | -1313849.10 |

| Reaction | Barrier Energy (kJ/mol) | Reaction Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Exo | 167.64 | -64.77 |

| Endo | 159.81 | -67.41 |

One explanation for this difference in barrier height comes from analysing the HOMO in each of the two transition states. In the endo structure it can be seen that the oxygen p-orbitals are favourably overlapping with the π-orbitals in the diene, whereas no such interaction occurs in the exo structure. It can also been seen that the the bridging carbon in 1,3-dioxole (i.e. the single carbon between the two oxygens) is further away from the cyclohexadiene ring in the endo transition state, by approximately 7.5%. As such the endo structure reduces the steric influence of each molecule on one another, preventing a high-energy clash.

Nf710 (talk) 19:37, 22 February 2018 (UTC) Your energiesd are correct but your discussion is very brief and you could have added some diagrams to help explain what you are saying. Nice understanding the the kenetics of the reaction however.

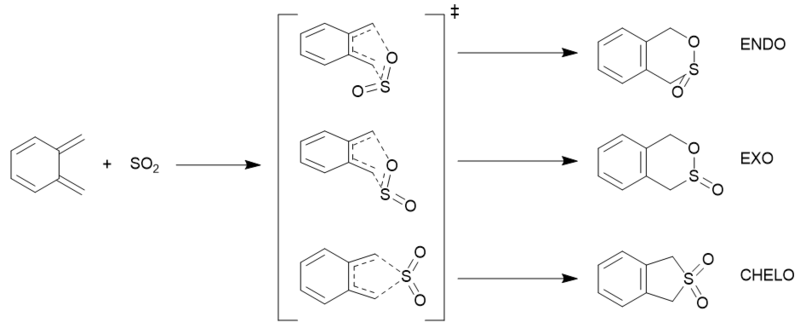

Exercise 3: Reactions of SO2 and o-xylylene

Here the various reactions of sulfur dioxide and ortho-xylylene are investigated — the exo and endo Diels–Alder reactions across the terminal ends of xylylene and across the xylylene ring, and the chelotropic reaction across the terminal carbons. Discussion of their thermochemistries and intrinsic reaction coordinates has also been made.

Investigation

First the structures of ortho-xylylene and sulfur dioxide were drawn, and then optimised to a minimum at the PM6 level. The resulting structures were then placed together in arrangements resembling a guess of the transition structures of the aforementioned five reactions. Bonds involved in the reactions had their lengths frozen, and in the case of the chelotropic reaction, the bond angles in the five-cycle transition were frozen. The frozen structures were then optimised to a minimum at the PM6 level. The resulting structures had their coordinates unfrozen, and optimisation + frequency calculated were performed on them to a transition state (using the Berny algorithm) at the PM6 level. The resulting transition structures were then submitted to an IRC calculation at the PM6 level. The final structures seen in the IRC results (the products) were then optimised to the PM6 level, alongside a frequency calculation.

Discussion of Thermochemistry

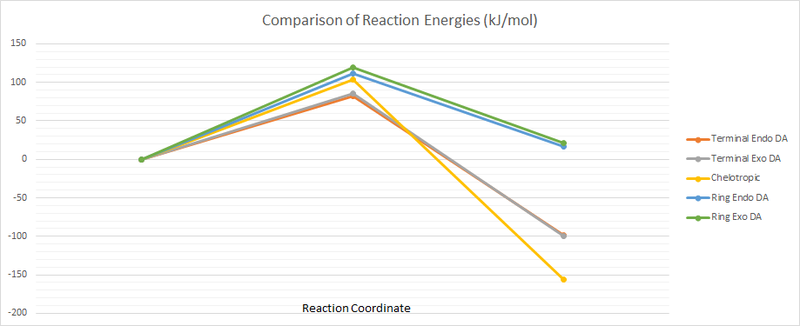

Tabulated below are the calculated sums of electronic and thermal free energies for the PM6-optimised reactants, products, and transition structures. From these values the barrier and reaction energies have been determined, and are also tabulated below. From these values it is seen that the endo Diels–Alder reaction that occurs across the terminal ends of xylylene has the lowest energy barrier, making it the kinetic product. Compared to its sister exo product, the endo product is predicted to form approximately 50 times faster under the Arrhenius equation. The alternate Diels–Alder reactions that occur across the xylylene ring occur much less readily, having energy barriers ca. 34 kJ/mol higher, making them much less kinetically favourable. Equally the energies of their products are much higher than for the terminal reactions (ca. 120 kJ/mol), making them thermodynamically unfavoured. The cheletropic reaction has a high energy barrier compared to the terminal DA reactions, but has a significantly lower energy final product. Having the lowest product energy makes the chelotropic reaction the thermodynamic product — one could attempt to produce this product by keeping the reaction time long whilst at high temperature and pressure.

(There is also a barrier between the endo and exo products which is lower than their DA barriers Tam10 (talk) 15:03, 26 February 2018 (UTC))

We can justify the low reactivity across the xylylene ring diene by looking at the new carbon-carbon double bond formed. In the terminal DA case the new double bond forms in the ring, aromatising the xylylene ring — a stabilising effect. Such an effect doesn't occur in the reaction across the ring, leading to it being higher in energy. The chelotropic reaction likely produces the lowest energy final product due to it producing the aforementioned aromatic ring, as well as producing a stable five-membered heterocycle.

The below figure further demonstrates the tabulated data, showing the relative energies of the products and transition states. Here it is noted that the values are plotted as deviations from the reactants, equivalent to setting the energy of the products as zero.

(equivalent to setting the energy of the reactants as zero Tam10 (talk) 15:03, 26 February 2018 (UTC))

| Species | Sum of free energies (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|

| o-xylylene | 467.473 |

| SO2 | -311.421 |

| Reactants | 156.052 |

| Terminal Endo TS | 237.763 |

| Terminal Endo Product | 56.968 |

| Terminal Exo TS | 241.748 |

| Terminal Exo Product | 56.327 |

| Chelotropic TS | 260.090 |

| Chelotropic Product | -0.003 |

| Ring Endo TS | 267.985 |

| Ring Endo Product | 177.256 |

| Ring Exo TS | 275.822 |

| Ring Exo Product | 176.709 |

| Reaction | Barrier Energy (kJ/mol) | Reaction Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Terminal Endo DA | 81.711 | -99.084 |

| Terminal Exo DA | 85.696 | -99.725 |

| Chelotropic | 104.038 | -156.055 |

| Ring Endo DA | 111.933 | 16.204 |

| Ring Exo DA | 119.770 | 20.657 |

(Not the clearest of diagrams - you should point out where the reactants are here, even if it seems obvious. If you use horizontal lines at the stationary points then you can include the values of barriers and reaction energies. This would make it easier to see the data Tam10 (talk) 15:03, 26 February 2018 (UTC))

Discussion on Transition States

The table below holds animations of the five intrinsic reaction coordinates, corresponding to each of the five reactions possible for this system. In contrast to the concerted nature of the previously covered Diels–Alder reactions, here they proceed in an asynchronous fashion — likely due the two different heteroatoms present. Over the course of the reactions which react at the terminal ends of xylylene it can be seen that the six-membered ring readily aromatises, likely a strong driving force in these reactions.

|

Conclusion

Overall the calculations performed over these exercises demonstrate the utility of simulation software in quickly describing reaction systems. The methodologies described have the downside of requiring prior knowledge and intuition of the transition structure. This has proved adequate for investigating the transition states of pericyclic reactions, where their forms are generally consistent, but for less familiar reactions this will not prove to be an readily applicable method. Using Gaussian to produce thermochemistry data has also provided a new tool of qualitatively appraising relative reactivities and subsequently, their rates of reaction.

References

[1] D.J. Wales, Energy Landscapes: Applications to Clusters, Biomolecules and Glasses, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003

[2] GaussView, Version 5.0.9, R. Dennington, T.A. Keith and J.M. Millam, Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission, KS, 2016

[3] Gaussian 09, Revision 9.5, M.J. Frisch et al., Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016

[4] J.J.P. Stewart, J. Mol. Model, 2007, 13, 1173–1213

[5] P.J. Stevens, F.J. Devlin, C.F. Chabalowski and M.J. Frisch, J. Phys. Chem., 1994, 98, 11623–11627

[6] R. Ditchfield, W.J. Hehre and J.A. Pople, JJ. Chem. Phys., 1971, 54, 724–728

[7] J. Tirado-Rives and W.L. Jorgensen, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2008, 4, 297–306

Appendix

Ex.1 Butadiene PM6 opt: File:Fht14butadienePM6.log

Ex.1 Ethene PM6 opt: File:Fht14ethenePM6.log

Ex.1 Ethene + Butadiene frozen opt: File:Fht14ethbutfropt.log

Ex.1 Ethene + Butadiene TS opt: File:Fht14ethbuttsopt.log

Ex.1 Ethene + Butadiene IRC: File:Fht14butethirc.log

Ex.2 Diene PM6 opt: File:Fht14dienepm6.log

Ex.2 Diene B3LYP opt: File:Fht14dienedft.log

Ex.2 Dioxole PM6: File:Fht14dioxolepm6.log

Ex.2 Dioxole B3LYP: File:Fht14dioxoledft.log

Ex.2 Frozen endo B3LYP: File:Fht14frendodft.log

Ex.2 Endo TS B3LYP: File:Fht14endotsdft.log

Ex.2 Endo IRC: File:Fht14endoirc.log

Ex.2 Endo product B3LYP opt: File:Fht14endoprod.log

Ex.2 Frozen exo B3LYP: File:Fht14frexodft.log

Ex.2 Exo TS B3LYP: File:Fht14exots.log

Ex.2 Exo IRC: File:Fht14exoirc.log

Ex.2 Exo product B3LYP opt: File:Fht14exoprod.log

Ex.3 SO2 opt: File:Fht14so2.log

Ex.3 Xylylene opt: File:Fht14xylylene.log

Ex.3 Terminal Exo TS: File:Fht14termexots.log

Ex.3 Terminal Endo TS: File:Fht14termendots.log

Ex.3 Chelotropic TS: File:Fht14chelots.log

Ex.3 Ring Exo TS: File:Fht14rexots.log

Ex.3 Ring Endo TS: File:Fht14rendots.log

Ex.3 Terminal Exo IRC: File:Fht14termexoirc.log

Ex.3 Terminal Endo IRC: File:Fht14termendoirc.log

Ex.3 Chelotropic IRC: File:Fht14cheloirc.log

Ex.3 Ring Exo IRC: File:Fht14rexoirc.log

Ex.3 Ring Endo IRC: File:Fht14rendoirc.log

Ex.3 Terminal Exo Prod: File:Fht14termoexop.log

Ex.3 Terminal Endo Prod: File:Fht14termendop.log

Ex.3 Chelotropic Prod: File:Fht14chelop.log

Ex.3 Ring Exo Prod: File:Fht14rexop.log

Ex.3 Ring Endo Prod: File:Fht14rendop.log