Rep:Mod:ew212

Structural Optimisation

The optimised geometry of a molecule gives its equilibrium conformation. A molecule can be optimised by assuming a fixed position for each nuclei (using the Born-Oppenheimer approximation) and solving the Schrodinger equation for the electron density (SCF calculation). The geometry is changed and the SCF calculation repeated (OPT calculation), with the lowest energy giving the equilibrium conformation. The structure at equilibrium has no net force acting upon it and therefore the energy is at a minimum as long as E = ∫F•dx.

Basis Sets

The number of functions used to describe a molecule's electronic structure in a calculation is defined by the basis set. Increasing the basis set gives a more accurate reproduction of the structure yet also increases the calculation difficulty and the time taken to perform the calculation.

BH3

To gain familiarity with GaussView, BH3 was optimised. The molecule was set up to have a trigonal planar geometry and BH bond lengths of 1.53Å, 1.54Å and 1.55Å. This allowed for analysis of a system with reduced symmetry (giving the point group CS).

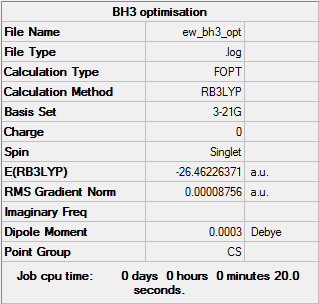

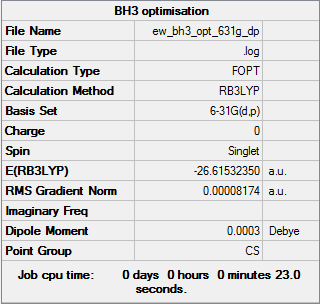

The optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and the log file here.

The optimum bond length is 1.1945 Å with an H-B-H angle of 120.0°. To be D3h, the molecule must have E, C3, σh, and 3C2 symmetry elements. As the molecule has a reduced symmetry due to changes in the x, y, z coordinates, it has E and σ operators, so must be classified as CS, with a minimum energy conformation at -26.46 au. The molecule can still be considered D3h to four decimal places.

The optimisation was verified in two ways: by reviewing the gradient, found in the summary, or by checking all of the parameters have converged in the convergence data. A gradient of less than 0.001 and a value less than the threshold for each item indicates an optimised structure. From the data table above it can be seen the BH3 molecule was successfully optimised.

The total energy graph below shows the energy of the molecule at each step in the optimisation, travelling down the potential energy surface (PES), while the RMS gradient at each step is shown in the second graph. The most negative energy structure is reflected by the smallest gradient in the final step (i.e. the PES is close to zero).

Improving the Basis Set

To improve the accuracy of the calculation, a 6-31G(d,p) basis set was used on BH3 and then compared to the results from using a 3-21G basis set.

The optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and the log file here.

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000217 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000105 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000919 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000441 0.001200 YES |

|

The average bond length (1.1927Å) is 0.0018Å less than that calculated with the smaller basis set and matches very well with an experimental bond length of 1.19001Å.[1] Although the energy using the improved basis set is 420 kJ/mol (0.153060 au) smaller that from the original set, it cannot be assumed that a lower energy state has been found as the calculations were run with different basis sets - only calculations with exactly the same parameters can be compared.

Pseudo-potentials

A pseudopotential aims to replace all non-valence electrons of an atom and its nucleus with an effective core potential (ECP) operator, which replaces the exact Hamiltonian operator in the Schrodinger equation. This produces a wavefunction with significantly fewer nodes which can therefore be more easily produced by a computer program as it reduces the size of the basis set. [2]

GaBr3

To optimise GaBr3, the point group was restricted to D3h with a medium level basis set and run on the high performance computer (HPC).

The optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below, the log file here and here DOI:10042/143683 .

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.001200 YES |

|

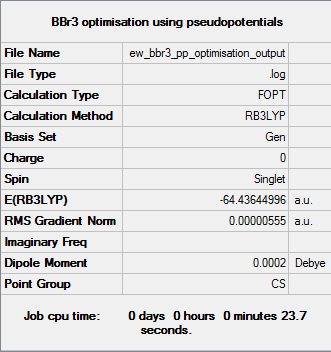

BBr3

As BBr3 contains both heavy and light atoms, it is necessary to use a mixture of pseudo-potentials and basis sets. The GEN basis set gives the option of applying different basis sets for individual atoms, while the "pseudo=read gfinput" command allows for the application of different pseudo-potentials for individual atoms. The 6-31G(d,p) basis set was assigned to the B atom and the LanL2DZ pseudo-potential was assigned to each Br atom.

The optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and here DOI:10042/143681 .

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000011 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000007 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000047 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000031 0.001200 YES |

|

Geometry Comparison between BH3, BBr3 and GaBr3

| BH3 | BBr3 | GaBr3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r(E-X) Å | 1.1927 | 1.1934 | 2.3503 |

| θ(X-E-X) degrees(º) | 120.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 |

BH3 and BBr3: Ligand comparison

Increasing the size of the ligand from hydrogen to bromine increases the bond length by 0.001 Å (0.059%), implying the B-H bond is stronger than the B-Br bond. Both ligands are diatomic, monovalent atoms and so form single covalent bonds. The valence electron of hydrogen is contained in a 1s orbital. As this orbital is located next to the nucleus, any bonded electrons from the 2p valence orbital of boron experience a large nuclear attraction to hydrogen, stabilising the bond. The valence electrons of bromine, however, are located in the 4p orbital. This orbital is much more diffuse than 1s and experiences a large shielding effect from core orbitals, decreasing nuclear attractive forces on the electrons and causing bromine to have a larger covalent radius. Furthermore, the energy match between Br(4p) and B(2p) is less than that between H(1s) and B(2p). This, as well as previously discussed factors, causes a weaker B-Br bond than B-H bond and hence the B-H bond is expected to be shorter.

BH3 and GaBr3: Central atom comparison

Increasing the size of the central atom from boron to gallium increases the bond length by 1.157 Å (96.94%), implying the B-Br bond is stronger than the Ga-Br bond. Both atoms can form trigonal planar geometries with +3 oxidation states. The 4p valence orbital of gallium matches the energy of the 4p bromine valence orbital very well. However, it has an atomic radius of 1.35 Å compared to the 0.85 Å atomic radius of boron. The Ga-Br internuclear distance is therefore much larger than that of B-Br, overriding the stability that similar energy levels brings and giving a stronger B-Br bond than Ga-Br.

Bonds

A bond is an interaction between the orbitals on two separate atoms and is caused by the electrostatic attractions between opposing charges. The equilibrium bond distance can be found at an energy minima, which is approximately the sum of the covalent radii of two atoms. It also gives a strong indication of the bond strength, as long bonds are usually weaker.

A range of bond strengths can occur, depending on the type of bond. A strong bond is usually a double or triple covalent or an ionic bond. An example is N≡N, which has an energy of 946 kJ/mol. A medium bond can also be covalent or ionic but usually contains a single bond, for example C-C, which has a dissociation energy of 348kJ/mol. Weak bonds are things such as dipole-dipole interactions, dispersion forces, or hydrogen bonds that are purely electrostatic interactions dependent only on the dipole of the molecule and tend to be approximately 20 kJ/mol.[3]

Gaussian uses a distance algorithm which determines whether there is a bond between certain atoms. At higher energy structures, the distance between certain atoms is greater than the predefined value so a bond is not seen in the program. This does not mean that a bond is not present in the structure, simply that the bond length is larger than that which Gaussian considers to be a bond.

Frequency Analysis

A frequency analysis is performed on a molecule to determine if a stationary point which is a minimum has been reached. The analysis is a second derivative of the PES and so gives positive value frequencies if the molecule is optimised to a minimum. A negative value indicates a transition state and more than one shows optimisation has not completed. To be able to accurately compare the frequency analysis and the optimisation, the same method and basis set must be used in both calculations.

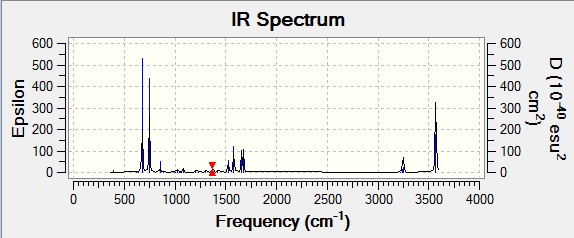

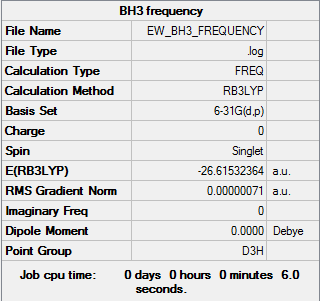

BH3

The optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and the log file here. The first line of low frequency data is all between ±15 cm-1, showing a structural energy minimum was found. The second line shows the frequencies of real vibrations in the molecule and relate to the symmetry of the molecule - in this case, from left to right, A2", E1', E1'.

| Summary data | Low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -10.1940 -10.1821 -3.1776 -0.0009 0.0579 0.4920 Low frequencies --- 1162.9850 1213.1461 1213.1463 |

Every molecule has 3N-6 vibrations which represent the motions of the centre of mass. The IR spectrum of BH3 would therefore be expected to have six peaks (contributed by the six vibrations seen below). However, the symmetric stretch does not invoke a change in dipole of the molecule and so is IR inactive and there are two sets of degenerate vibrations (1213.15cm-1 and 2715.68cm-1) which give the same IR peak. Therefore only three peaks are seen on the spectrum.

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1162.98 | 92.5671 | Yes | Out-of-plane symmetric bend (wagging) |

| 1213.15 | 14.0555 | Very slight | In-plane asymmetric bend/angle deformation (rocking) |

| 1213.15 | 14.0549 | Very slight | In-plane asymmetric bend (scissoring) |

| 2582.54 | 0.0000 | No | Symmetric stretch |

| 2715.68 | 126.3333 | Yes (strong) | Asymmetric stretch/angle deformation |

| 2715.68 | 126.3273 | Yes (strong) | Asymmetric stretch |

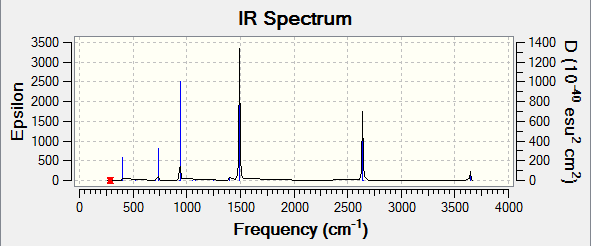

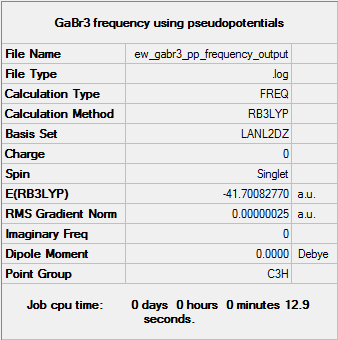

GaBr3

The first line of low frequency data is all between ±15 cm-1, showing a structural energy minimum was found. The second line shows the frequencies of real vibrations in the molecule and relate to the symmetry of the molecule - in this case, from left to right, A2", E1', E1'.

The optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and here DOI:10042/146768 .

| Summary data | Low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.4881 -0.0015 -0.0002 0.0097 0.6540 0.6540 Low frequencies --- 76.3920 76.3924 99.6767 |

Again, three peaks can be seen in the IR due to two degenerate vibrations (3.3451cm-1 and 316.18cm-1) and one IR inactive vibration (symmetric stretch).

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 76.39 | 3.3451 | Yes (Slight) | In-plane asymmetric bend (scissoring) |

| 76.39 | 3.3450 | Yes (Slight) | In-plane asymmetric bend/angle deformation (rocking) |

| 99.68 | 9.2166 | Yes (Slight) | Out-of-plane symmetric bend (wagging) |

| 197.33 | 0.0000 | No | Symmetric stretch |

| 316.18 | 57.0655 | Yes (strong) | Asymmetric stretch |

| 316.18 | 57.0655 | Yes (strong) | Asymmetric stretch/angle deformation |

Comparison between BH3 and GaBr3

The vibrational frequencies of BH3 (2715.68-1162.98cm-1) are much larger than those of GaBr3 (316.18-76.39cm-1). Borane has a much smaller mass and as can be seen from f = (1/2π)√(k/μ), where f is the vibration and μ the reduced mass, will therefore have higher frequencies. This is consistent with the smaller bond length, and higher bond strength, of B-H, as the energy of each vibration will be higher for a stronger bond.

| BH3 | GaBr3 |

|---|---|

|

|

The A2" modes occur at different vibrations in each molecule. The A2" mode is the lowest BH3 vibration, at 1162.98cm-1 with an intensity of 93. It is the highest bending vibration in GaBr3, at 99.68cm-1 with an intensity an order of magnitude smaller. The E' modes have not changed as much as the A2" modes, therefore showing a reordering of the modes. This is most likely due to the increased mass of GaBr3. Additionally, looking at the direction vectors in BH3, it can be seen that it is primarily the hydrogen atoms which move with high frequencies, due to their lighter mass relative to boron. In GaBr3, the direction vectors show that the gallium centre moves more during this vibration, with a larger displacement vector due to the relative weakness of the Ga-Br bond compared to the B-H bond.

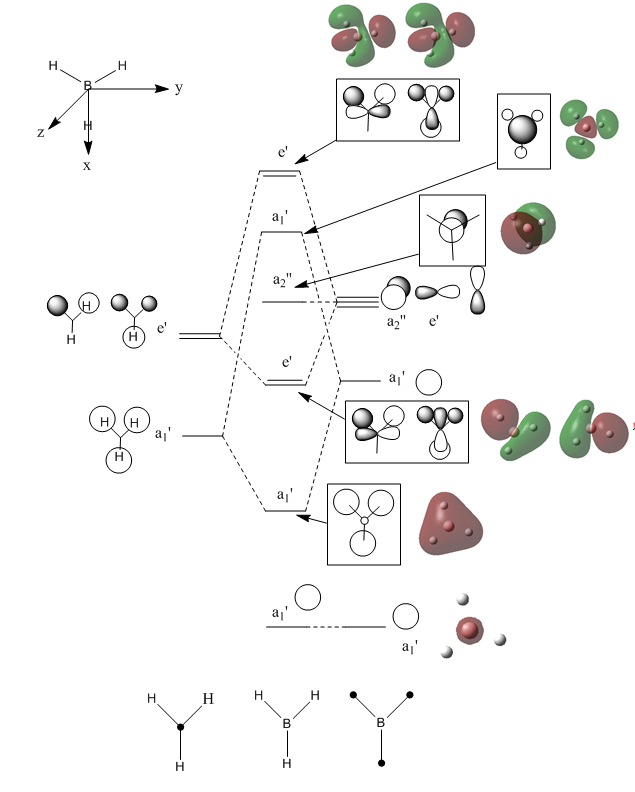

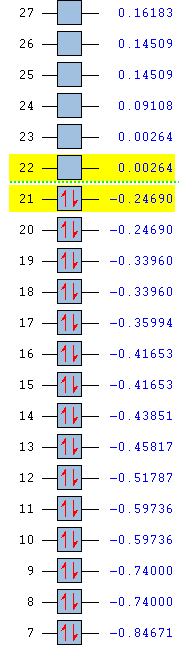

Calculating the MO of BH3

The energy calculation for the BH3 MO can be found here DOI:10042/144326 and the BH3 molecular orbital diagram can be seen below, alongside the real MOs. The predicted LCAO MO diagram has been taken from Hunt Research Group Teaching Page. [4]

The qualitative model can be seen to be a good approximation of the LCAO MOs. The HOMO-1, LUMO and LUMO+1 orbitals are all in good agreement with the prediction. Overall, however, the real orbitals are more diffuse, with differing contributions by each atomic orbital. For example, the real MOs of the degenerate e' orbital show the bonding and antibonding contributions to be spread over half of the molecule each yet the LCAO MOs of these orbitals show that there is a distinctive contribution from both the B and H3 fragments. There is still a strong correlation between both the real and LCAO MOs as the relative positions of the bonding and antibonding orbitals have been correctly predicted, even though the individual MOs have not been exactly replicated. The calculation is therefore useful in predicting MO ordering, but should not be relied upon for accurate representation of a molecule's MOs.

NBO Analysis of NH3

A natural bond order analysis can be used, among other things, to show the charge distribution across a molecule. It divides the electron density of the molecule into atomic-like orbitals. These are then used to show the contribution each atom makes to a 2c-2e bond, also giving the hybridisation of each atom.

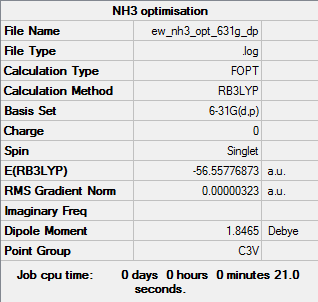

Structural Optimisation

The optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below, the log file here. It can be seen to have a C3v point group.

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000012 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES |

|

Frequency Analysis

The frequency analysis was run using the same method and basis set as the optimisation. The first line of low frequency data is all between ±15 cm-1, showing a structural energy minimum was found. The second line shows the frequencies of real vibrations in the molecule and relate to the symmetry of the molecule - in this case, from left to right, A, E, E. The frequencies of the molecule are shown by the data below and the log file here.

| Summary data | Low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0138 -0.0030 0.0013 7.0781 8.0927 8.0932 Low frequencies --- 1089.3840 1693.9368 1693.9368 |

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1089.38 | 145.4273 | Yes (strong) | Out-of-plane symmetric bend |

| 1693.94 | 13.5570 | Very slight | In-plane asymmetric bend/angle deformation |

| 1693.94 | 13.5571 | Very slight | In-plane asymmetric bend |

| 3461.30 | 1.0595 | No | Symmetric stretch |

| 3589.86 | 0.2699 | No | Asymmetric stretch/angle deformation |

| 3589.86 | 0.2699 | No | Asymmetric stretch |

MO and NBO Analysis

The MO file for population analysis can be found here DOI:10042/146700 .

| Atom | Charge |

|---|---|

| Nitrogen | -1.125 |

| Hydrogen | 0.375 |

The NBO analysis shows that the electronegative nitrogen contributes towards 69% (25% s + 75% p orbital)of an N-H bond, with 31% of the bonding coming from the slightly positive hydrogen. It shows nitrogen has formed four sp3 hybrid orbitals, one bonding with each sAO hydrogen and one lone pair. This is consistent with the tetrahedral structure and C3v symmetry that ammonia has. All N-H bonds have the same energy, whilst the lone pair is higher in energy. It can also be seen from the NBO summary that the valence orbitals are higher in energy than the core orbitals.

Association Energy of NH3BH3

NH3 and BH3 form a dative σ-bond between the nitrogen and boron centres, where the N(lone pair) is donated to the electropositive boron atom. A dative bond is longer and weaker than a covalent bond between the same atoms, and is more affected by inductive effects.

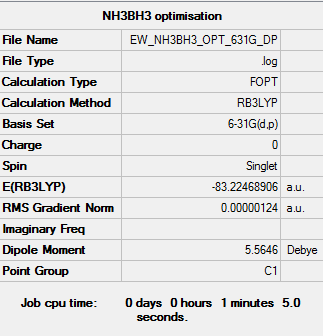

Structural Optimisation

The optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and the log file here.

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000002 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000001 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000026 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000009 0.000040 YES |

|

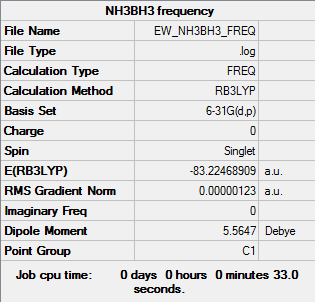

Frequency Analysis

The first line of low frequency data is all between ±15 cm-1, showing a structural energy minimum was found. The second line shows the frequencies of real vibrations in the molecule and relate to the symmetry of the molecule - in this case, from left to right, A, A, A. The frequencies of the molecule are shown by the data below and the log file here, which also shows the individual vibrations of the molecule, both IR active and inactive.

| Summary data | Low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -2.9061 -1.2382 -0.0009 -0.0008 -0.0007 4.2215 Low frequencies --- 263.4023 632.9672 638.4289 |

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 263.40 | 0.0000 | No | Bend |

| 632.97 | 14.0101 | Yes | N-B stretch |

| 638.43 | 3.5480 | No | Bend |

| 638.43 | 3.5470 | No | Bend |

| 1069.16 | 40.5092 | Yes | Bend |

| 1069.17 | 40.5089 | Yes | Bend |

| 1196.18 | 108.9760 | Yes (strong) | Bend |

| 1203.53 | 3.4687 | No | Bend |

| 1203.56 | 3.4696 | No | Bend |

| 1328.84 | 113.6075 | Yes | Bend |

| 1676.05 | 27.5659 | Yes | Bend |

| 1676.06 | 27.5659 | Yes | Bend |

| 2471.98 | 67.2015 | Yes | N-H symmetric stretch |

| 2532.08 | 231.2470 | Yes (strong) | N-H asymmetric stretch |

| 2532.09 | 231.2385 | Yes (strong) | N-H asymmetric stretch |

| 3464.09 | 2.5110 | No | B-H symmetric stretch |

| 3581.12 | 27.9537 | Yes | B-H asymmetric stretch |

| 3581.14 | 27.9535 | Yes | B-H asymmetric stretch |

Relative Energies and Dissociation

The dissociation energy of the N-B bond can be calculated by comparing the energies of the individual fragments and final molecule. To make the energies comparable, the same methods and basis sets were used in all calculations.

| Molecule | Energy (au) |

|---|---|

| NH3 | -56.5577687 |

| BH3 | -26.6153235 |

| NH3BH3 | -83.2246891 |

ΔE = E(NH3BH3) - [E(NH3) + E(BH3)]

ΔE = -83.2246891 -[-56.5577687 + -26.6153235] = -0.0515969 au = -135.47 kJ/mol

Whilst this is relatively strong for a dative bond, it is a medium-weak bond in regards to the examples discussed earlier, although still much stronger than any intermolecular interactions. A literature value is reported for this bond at -115.06±2.09 kJ/mol.[5] The deviation of the above calculated value compared to the literature value could be due to error accumulated in the dissociation energy calculation and the basis set used. Improving the accuracy of the basis set would give a value closer to that reported in the literature.

Aromaticity

Aromaticity in a molecule can be comfirmed using Huckel's rules. A molecule must have 4n+2 delocalised π electrons, be cyclic, planar, and every atom in the ring must be able to contribute to delocalisation.

The purpose of this project was to relate aromatic compounds to their molecular orbitals (MOs). C-H units in benzene were exchanged with isoelectronic units containing boron and nitrogen. The conformers, vibrations and MOs of benzene, boratabenzene, pyridinium and borazine were computed using the same basis set and analysed.

Benzene

Benzene is an organic, cyclic molecule with the formula C6H6. Each carbon contributes one electron towards the π cloud, which is formed above and below the ring. Benzene therefore contains a continuous π bond and is aromatic.

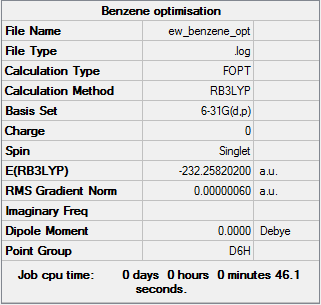

Structural Optimisation

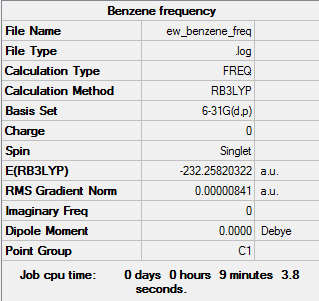

Successful optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and the log file here DOI:10042/149954 . Benzene can be seen to have D6h symmetry.

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000002 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.000040 YES |

|

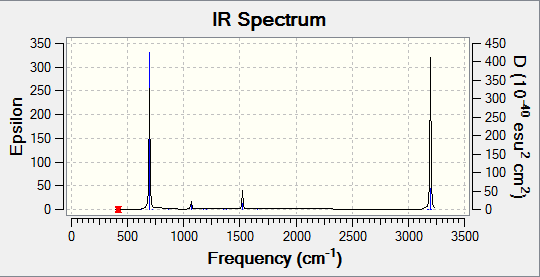

Frequency Analysis

The frequency analysis was run using the same method and basis set as the optimisation. The first line of low frequency data is all between ±15 cm-1, showing a structural energy minimum was found. The second line shows the frequencies of real vibrations in the molecule and relate to the symmetry of the molecule - in this case, from left to right, E2u, E2u and E2g. The frequencies of the molecule are shown by the data below and the log file here DOI:10042/149963 .

| Summary data | Low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -10.2549 -5.6651 -5.6651 -0.0056 -0.0055 -0.0010 Low frequencies --- 414.5451 414.5451 621.0429 |

Benzene contains six equivalent C-C and C-H bonds, therefore there are six equivalent C-C and C-H stretches. In addition to this, there are several in and out of plane bends. However, as benzene has D3h symmetry and is therefore highly symmetric, most of these vibrations will be IR inactive, such as ring expansions. Furthermore, any stretches or out-of-plane bends will cause para carbons to move in opposite directions, preventing a change in dipole and so the vibrations are inactive.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR Active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 414.54 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 414.55 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 621.06 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 621.06 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 695.82 | 74.2405 | yes | bend (wag) |

| 718.38 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 865.31 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 865.42 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 974.61 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 974.70 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 1013.30 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 1017.79 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 1019.51 | 0.0000 | no | stretch (ring expansion) |

| 1066.42 | 3.3835 | very slight | bend |

| 1066.45 | 3.3850 | very slight | bend |

| 1179.65 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 1202.50 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 1202.53 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 1355.49 | 0.0000 | no | C-C stretch |

| 1380.69 | 0.0000 | no | bend |

| 1524.42 | 6.6269 | very slight | stretch |

| 1524.44 | 6.6229 | very slight | stretch |

| 1652.65 | 0.0000 | no | stretch |

| 1652.65 | 0.0000 | no | stretch |

| 3171.73 | 0.0001 | no | stretch |

| 3181.27 | 0.0000 | no | stretch |

| 3181.34 | 0.0000 | no | stretch |

| 3196.94 | 46.6221 | yes | stretch |

| 3197.01 | 46.6130 | yes | stretch |

| 3207.56 | 0.0000 | no | C-H stretch |

MO and NBO Analysis

The MO file for population analysis can be found here DOI:10042/149982

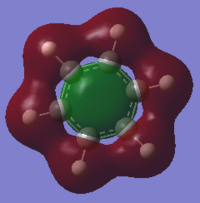

Aromaticity arises when a molecule obeys Huckel's rule, in that it must have 4n+2 electrons in the delocalised π cloud. The molecule must also be cyclic, planar, and every atom in the ring must be able to contribute to delocalisation. Benzene contains 6π electrons, giving n=1 and so fulfilling these criteria. It's aromaticity is also shown by the MOs, which spread across the whole molecule.

The first molecule to support aromaticity is the a2u MO which is composed of six pz carbon orbitals. The LCAO indicates individual bonding π orbitals are formed above and below the ring plane. The real MO shows that instead one large cloud of delocalised electron density is formed above and below the ring, one bonding and one antibonding. This represents the resonance forms which appear in a cyclic alkene.

| Atom | Charge |

|---|---|

| Carbon | -0.239 |

| Hydrogen | 0.239 |

The NBO analysis shows that each carbon contributes equally towards each C-C (35.2% s + 64.8% p orbital) and C=C (100% p orbital) bond. The electronegative carbons contribute 62.0% (29.6% s + 70.4% p orbital) of each C-H bond, with 37.8% of the bonding coming from the electropositive hydrogen. This is consistent with the highly symmetric structure and C6 rotation that benzene has. All C-C bonds have the same energy, whilst the C-H bonds are lower in energy and the C=C bonds lower still. As there is a difference in energy between C-C and C=C, the calculation has not taken into account any delocalisation, which is a cause of error in the calculations. It can also be seen from the NBO summary that the valence orbitals are higher in energy than the core orbitals.

The NBO shows the ring carbons are more electronegative than the hydrogens supporting the theory of a delocalised π system. The NBO also shows the π orbitals have an occupancy of 1.66 electrons compared to the 2 electrons assumed in the MOs. This confirms the delocalised electron density that the real MOs show in the a2u, e1g, and a1g orbitals among others. These MOs also indicate delocalisation occurs above and below the ring.

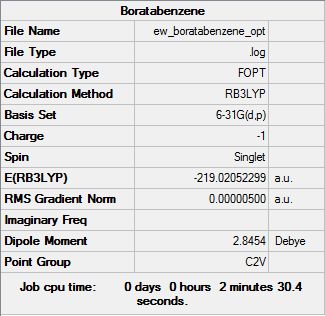

Boratabenzene

Boratabenzene is isoelectronic with benzene, with the formula [C5H6B]-. The negative charge means it acts as strong π-donating ligand.

Structural Optimisation

Successful optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and the log file here DOI:10042/157657 . Boratabenzene can be seen to have C2v symmetry.

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000003 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000044 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000013 0.000040 YES |

|

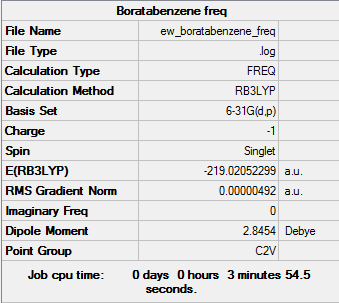

Frequency Analysis

The frequency analysis was run using the same method and basis set as the optimisation. The first line of low frequency data is all between ±15 cm-1, showing a structural energy minimum was found. The second line shows the frequencies of real vibrations in the molecule and relate to the symmetry of the molecule - in this case, from left to right, B1, A1 and B2. The frequencies of the molecule are shown by the data below and the log file here DOI:10042/157710 .

| Summary data | Low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -7.1850 -0.0006 0.0005 0.0006 3.7532 4.3181 Low frequencies --- 371.2982 404.4154 565.0738 |

MO and NBO Analysis

The MO files and analysis can be found here DOI:10042/157741 .

Pyridinium

Pyridinium is isoelectronic with benzene, with the formula [C5H6N]+. In pyridine, the lone pair on nitrogen is not part of the aromatic ring and so can easily be protonated to form the conjugate acid.

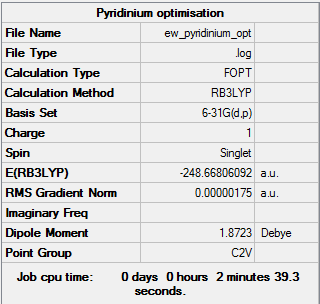

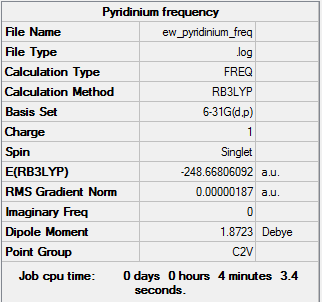

Structural Optimisation

Successful optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and the log file here DOI:10042/157774 . Pyridinium can be seen to have C2v symmetry.

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000003 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000001 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000007 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.000040 YES |

|

Frequency Analysis

The frequency analysis was run using the same method and basis set as the optimisation. The first line of low frequency data is all between ±15 cm-1, showing a structural energy minimum was found. The second line shows the frequencies of real vibrations in the molecule and relate to the symmetry of the molecule - in this case, from left to right, B1, A2 and A1. The frequencies of the molecule are shown by the data below and the log file here DOI:10042/157789 .

| Summary data | Low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -9.3821 -2.9805 -0.0004 -0.0003 0.0005 1.0287 Low frequencies --- 391.9009 404.3423 620.1995 |

MO and NBO Analysis

The MO file and analysis can be found her DOI:10042/157847 .

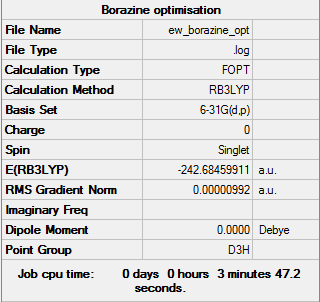

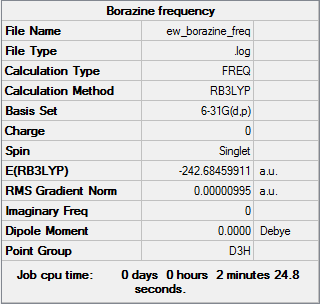

Borazine

Borazine is isoelectronic and isostructural with benzene, with the formula (BH)3(NH)3. It is, also like benzene, a colourless liquid and is therefore known as "inorganic benzene".[6]

Structural Optimisation

Successful optimisation of the molecule is shown by the data below and the log file here DOI:10042/157882 . Borazine can be seen to have D3h symmetry.

| Summary data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000010 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000005 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000056 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000018 0.000040 YES |

|

Frequency Analysis

The frequency analysis was run using the same method and basis set as the optimisation. The first line of low frequency data is all between ±15 cm-1, showing a structural energy minimum was found. The second line shows the frequencies of real vibrations in the molecule and relate to the symmetry of the molecule - in this case, from left to right, E", E" and A2". The frequencies of the molecule are shown by the data below and the log file here DOI:10042/157897 .

| Summary data | Low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -4.5793 -4.5358 -3.4227 -0.0035 0.0134 0.0194 Low frequencies --- 289.7258 289.7270 404.5169 |

MO and NBO Analysis

The MO file and analysis can be found here DOI:10042/157916 .

Comparison of Isoelectronic Molecules

Molecules are isoelectronic when they contain the same number of electrons and the same number and connectivity of atoms. All the molecules discussed are aromatic (n=1) with 6π delocalised electrons. They all exhibit planar structures with each bond in the ring contributing to the π system formed above and below the ring.

Charge Distribution

The charge distributions for each isoelectronic molecules are below. Atoms labelled A are part of the ring, where A1 is the top atom and then moves clockwise. H represents the hydrogen on each numbered ring atom respectively, moving clockwise. The grey atoms in the ring represent carbon, pink atoms represent boron and blue represent nitrogen. All atoms outside of the ring are hydrogen.

| Benzene | Boratabenzene | Pyridinium | Borazine |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Molecule | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene | -0.239 | -0.239 | -0.239 | -0.239 | -0.239 | -0.239 | 0.239 | 0.239 | 0.239 | 0.239 | 0.239 | 0.239 |

| Boratabenzene | 0.202 | -0.588 | -0.250 | -0.340 | -0.250 | -0.588 | -0.097 | 0.184 | 0.179 | 0.186 | 0.179 | 0.184 |

| Pyridinium | -0.476 | 0.071 | -0.241 | -0.122 | -0.241 | 0.071 | 0.483 | 0.285 | 0.297 | 0.292 | 0.297 | 0.285 |

| Borazine | -1.102 | 0.747 | -1.102 | 0.747 | -1.102 | 0.747 | 0.432 | -0.077 | 0.432 | -0.077 | 0.432 | -0.077 |

The distribution of charge around a molecule is reliant on electronegativity of each atom. Electronegativity is dependent on the effective nuclear charge of an atom and shielding around the nucleus. In general, it increases across a period and up a group. Literature values for each element can be found below.[6]

| Element | ΧP |

|---|---|

| Carbon | 2.25 |

| Hydrogen | 2.20 |

| Boron | 2.04 |

| Nitrogen | 3.04 |

Benzene is a highly symmetric molecule with C6 rotation. The identical environments for each carbon and hydrogen mean there is identical charge distribution on each atom of each element. Carbon is more electronegative than hydrogen so retains a larger proportion of the electron density. The molecule is neutral and so has an overall charge of zero (-0.239*6 + 0.239*6).

In boratabenzene, the A1 carbon is replaced with boron, a more electropositive atom which can be found in group 3. Boron holds the least electron density, with a charge of +0.202 whilst A2 and A6 - the two carbon atoms next to boron - have the largest negative charge (-0.588). This is due to the electronegativity difference between the two elements. As electronegativity is the measure of the tendency of atoms to attract electrons, a larger electronegativity should lead to a more negative charge distribution on that atom. In this case, this is true. The carbons meta to boron (A3 and A5) have a less negative charge (-0.250), similar to those in benzene, and the para-carbon (A4) at -0.340. The electropositive boron has a larger effect on the ortho and para carbons as it is adjacent to A2 and A6 whilst the electron density spreads above and below the ring to affect A4. The hydrogens are similarly affected. H1 is the only negative hydrogen (-0.097) as it is directly attached to the more electropositive boron. H2 to H6 are in the range of 0.179-0.186, with more positive charges adjacent to more negative carbons. Benzene hydrogens are more positive by 0.05-0.06 as boratabenzene has an overall negative charge so has more electron density to spread over the molecule.

In pyridinium, the A1 carbon is replaced with nitrogen, a more electronegative atom which can be found in group 5. It holds the most electron density, with a charge of -0.476 whilst A2 and A6 - the two ortho carbons - have the largest positive charge (0.071) of all the ring atoms. The arguments are effectively the same as for boratabenzene, with the same ortho para directing effect present for charge distribution. The hydrogen H1 is extremely positive (0.483) in comparison to the others due to the attraction of electrons towards the nitrogen centre. There is a much larger difference between the charges on the pyridinium atoms than on the boratabenzene atoms. Nitrogen and carbon have a larger electronegativity difference than boron and carbon so form a more polar bond. Electrons are attracted away from the centre of the X-C bond to a larger degree when X=N due to the increased differences in effective nuclear charge, and hence stronger attractive forces. When X=B, the bond is less polar as the nuclear charges are more similar.[7]

| Element | Zeff |

|---|---|

| Carbon | 3.14 |

| Hydrogen | 1.00 |

| Boron | 2.421 |

| Nitrogen | 3.83 |

In borazine, three B-N units have replaced three C-C units. The molecule is more symmetric, with a C3 rotation, and all boron and nitrogen atoms are in the same environment as the other atoms of that element in the molecule. Therefore the charges on boron (0.747) and nitrogen (-1.102) are constant. The same is true for the hydrogens. The hydrogens bonded to boron have a slightly negative charge (-0.077), similar to that in boratabenzene (-0.097). The negative charge is larger in boratabenzene due to the less electronegative carbon ring, as opposed to the B-N bonds present in borazine. The change is small however as the adjacent atom is the same and this has the dominant effect on the charge distribution to the hydrogen. The hydrogens bonded to nitrogen have a positive charge (0.432), similar to that in pyridinium (0.483). This is again for the reasons stated previously. The less electropositive carbon ring in pyridinium, in comparison to the adjacent borons in borazine, causes more electron density to be spread onto the hydrogen due to the smaller change in electronegativity.

Overall, it can be seen that each boron atom is donating electron charge to its adjacent atoms while each nitrogen is accepting charge from each adjacent atom.

Valence Occupied MOs

| Benzene | Boratabenzene | Pyridinium | Borazine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real |

|

|

|

|

| LCAO |

|

|

|

|

| Energy (au) | -0.51787 | -0.28949 | -0.79009 | -0.55137 |

| Ordering | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 |

| Degeneracy | No | No | No | No |

The above benzene MO shows carbon sp2 orbitals interacting with hydrogen s orbital, to form a bonding MO. There is medium through space bonding between each hydrogen and each ring atom and a large bonding between carbons para to each other through the ring.

Boratabenzene and pyridinium both show similar bonding, although there are some differences in orbital size, leading to differing energies. Boratabenzene has two through-space bondings between hydrogens fewer than benzene, which occur between the hydrogens ortho and meta to boron. The electropositive boron has less electron density on it than the other ring substituents and so has a smaller orbital, and a weaker bonding contribution. This causes a build up of electron density, as previously stated, on the para-carbon and a deficiency on the meta carbons. This electron withdrawal from the meta carbons gives the lack of through-space bonding. The reduced hydrogen bonding and smaller boron orbital weaker bonding orbital and so a higher energy (-0.28949 au) relative to benzene (-0.51787 au).

Pyridinium is the opposite case to boratabenzene. Nitrogen is more electronegative so has an increased electron density on the atom and a larger interacting orbital giving a larger density around the nitrogen hydrogen and meta-hydrogens than present in boratabenzene, as shown in the MO. The meta-carbons have a larger electron density than in the other molecules and so their orbitals have an increased bonding contribution. The para-hydrogen and carbon do not participate in this MO as there is too little electron density around the atoms. The increase in bonding character between the ring orbitals and their substituents, between the hydrogens, and between the larger ring orbitals give a lower energy (-0.79009 au) relative to the others.

There is a marked difference in the contributions each atom gives towards the MO in borazine. Hydrogen substituents on boron do not contribute to the orbital, while the hydrogens exhibit a very large bonding character with each nitrogen. This is again due to the large electronegativity differences in the molecule. The electronegative nitrogen draws electron density towards itself, away from its substituents, and causing a large bonding overlap with them. This can also be seen in the boron-nitrogen p orbital overlap MO. Boron, on the other hand, is electropositive and so does not draw its substituents into a bonding overlap. Therefore, no through space, nor through bond, overlap is observed. The boron orbitals are furthermore much smaller than the nitrogen orbitals, decreasing the through space bonding interactions between ring atoms. Overall, the nitrogen and boron negate each other's effects and give an energy (-0.55137 au) similar to that of benzene. The MO is also found at a lower order than the others due to mixing of MOs - two degenerate s MOs are raised in energy.

| Benzene | Boratabenzene | Pyridinium | Borazine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real |

|

|

|

|

| LCAO |

|

|

|

|

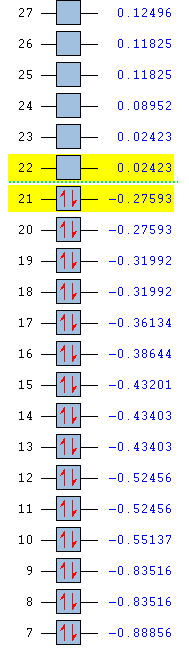

| Energy (au) | -0.35994 | -0.13209 | -0.64062 | -0.36134 |

| Ordering | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Degeneracy | No | No | No | No |

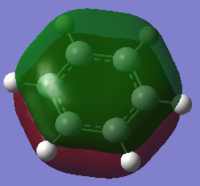

The above MO shows the delocalised π system, consisting of pz orbitals giving strong through space bonding above and below the ring plane. Each molecule shows very similar bonding and orbital interaction with the only difference being the electron density around the respective substituted ring atom and their hydrogen substituent. The effects caused by these substituents on the ortho, meta and para-carbons are also present, although the effects are minimised due to the out of plane orbitals interacting. As the electron density build up does not contribute to any orbital overlap in this MO, it only affects the through space bonding between ring substituents.

As explained above, boron destabilises the ring via the decreased through space interactions due to its more electropositive nature. This increases the energy of the MO in boratabenzene. Likewise, nitrogen stabilises the ring through its electronegative nature, giving stronger through space interactions in the ring. This decreases the energy of the MO in pyridinium.

The MOs are all in the 17th position, due to the orbital's aromatic character - it is the lowest energy orbital to display this fully and as such is not degenerate.

Whilst the LCAO model is useful in visualising the specific atomic orbital arrangements produced by the MO, it does not show the contribution each pz orbital makes to the electron density. Furthermore, the MO does not explain why different atoms change the energy of the MO. It is therefore important to consider both the charge distribution information given by the NBO and the orbital contributions given by the MO to build a full picture of the intramolecular interactions.

| Benzene | Boratabenzene | Pyridinium | Borazine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real |

|

|

|

|

| LCAO |

|

|

|

|

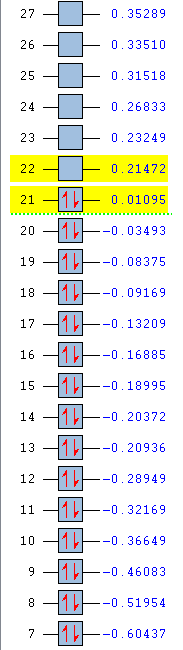

| Energy (au) | -0.24690 | 0.01095 | -0.50847 | -0.27593 |

| Ordering | 21 | 21 | 20 | 21 |

| Degeneracy | Yes | No | No | Yes |

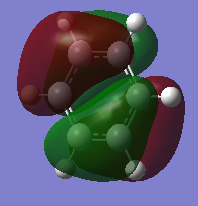

The above MOs represent the HOMO of each molecule, excluding pyridinium. There is medium through space bonding above and below the plane between three X-H units and 2 nodes resulting in through space antibonding, para to each other.

Benzene is a highly symmetric molecule with a σh plane of symmetry. The bonding and antibonding content is the same as each bonding and antibonding lobe is identical, confirming the uniform distribution of electron density predicted by the NBO. Half of the orbitals are in phase and half out of phase, with two above and two below the ring, giving four areas of electron density - each of which is half the size of the MOs in the 17th position. The MO is degenerate due to this symmetry.

Boratabenzene has reduced symmetry compared to benzene. The electropositive boron atom causes two larger, more diffuse electron clouds around the C-B-C unit in comparison to the other half of the molecule, which is more electronegative so holds the electrons more tightly. This increased diffusion raises the energy of the HOMO, also due to the decreased through space bonding between boron and its substituents, as discussed previously. The reduced symmetry causes degeneracy to break.

Pyridinium has the same symmetry as boratabenzene and so would be expected to be the HOMO of the molecule. However, the broken degeneracy caused by the reduced symmetry causes this MO to be the HOMO-1. The energy is also much lower than that of benzene (-0.50847 au). The electronegativity of the nitrogen holds the electron density tightly such that the orbitals on the ortho-carbons do not participate in this MO. This is compensated for by the meta and para-carbons which have a large charge density on less electronegative atoms, leading to more diffuse orbitals.

The MO of borazine is similar to that of benzene. The N-B-N unit has a more diffuse electron cloud than that of the B-N-B unit. This is due to the relative electronegativities of the central unit atom and the attractive forces they exhibit on their electron density, as previously disussed. Similar to benzene, borazine is a highly symmetric molecule with a σh plane of symmetry, leading to degeneracy of the HOMO.

Effect of Substitution

Altering a structure will alter the entire MO. The change in atoms changes both the distribution of electron density around the ring due to the changes in electronegativity and reduces the symmetry of the molecule. This changes the energies of each MO and the symmetry label - changing the MO structure and bonding/antibonding character.

| Molecule | Symmetry |

|---|---|

| Benzene | D6h |

| Boratabenzene | C2v |

| Pyridinium | C2v |

| Borazine | D3h |

Changing a single atom in the ring reduces the symmetry of the molecule so that the ring is no longer made up of repeating units. This removes all degeneracy from the molecule as no two wavefunctions are the same, and so no two relative energies are idential. Boratabenzene and pyridinium therefore show no degeneracy in their MOs. Borazine, however, contains a BH-NH repeating unit and so has degenerate MOs.

Changing substituents also affects the stability of the molecule. Exchanging CH for NH+, as in pyridinium, increases the stability of the molecule by reducing the relative energies of each MO in relation to benzene. Its HOMO occurs at -0.47886 au and so is the most stable aromatic investigated. The more electronegative nitrogen exerts a larger attractive force on the electrons in the ring than carbon, holding the electron density more tightly. This results in a less diffuse electron cloud, causing energy level stabilisation. Because of this stabilisation, the LUMO is lower in energy than benzene and so is more open to reduction, but is much less open to electrophilic attack.

Exchanging CH for BH-, as in boratabenzene, has the opposite effect and reduces the stability of each MO in relation to benzene. Its HOMO occurs at 0.01095 au and is the least stable aromatic investigated. The electropositive boron somewhat repels the electrons, resulting in a more diffuse electron cloud as the five electronegative carbons cannot easily stabilise the 6π electrons. This destabilises each energy level and raises the LUMO energy far above that of benzene, leaving it reactive towards electrophilic attack. The molecule is, however, not susceptible towards nucleophilic attack as it would add an electron into an unoccupied high energy orbital.

Borazine is similar in both energies, structure and degeneracy to benzene. They both have repeating units which allow for an equal spread of electron distribution across the molecule. The strong attractive forces of the electronegative nitrogen negate the repulsion of electrons by the electropositive boron. This produces bonds with more ionic character than those found in benzene, which are purely covalent. This overall balance of electronegativites causes borazine to be slightly stabilised in relation to benzene, with its HOMO at -0.27539 au as opposed to -0.24690 au.

| Benzene | Boratabenzene | Pyridinium | Borazine |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Conclusion

Overall it was seen that, although the aromatic molecules are isoelectronic, changing the substituents still widely affects the MO of each molecule. Boratabenzene is the least stable molecule due to the reduced symmetry and increased electropositive substituent (boron) in comparison to benzene and carbon. Pyridinium is the most stable, even with the reduced symmetry, due to the highly electronegative nitrogen substituent in comparison to benzene. It was found that borazine has a slight increase in stabilisation over benzene as the nitrogen negates the boron electropositivity. It was also discovered that the more electronegative the ring substituents, the tighter the electron density around it.

References

- ↑ Kawaguchi K. J. Chem. Phys. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of the BH3 ν3 band. 2007, 96 (3411). DOI:10.1063/1.461942

- ↑ Schwerdtfeger p. ChemPhysChem. The Pseudopotential Approximation in Electronic Structure Theory. 2011, 12 (17). DOI:10.1002/cphc.201100387

- ↑ Atkins P., de Paula J. Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press. Great Britain. 8th ed. 2006.

- ↑ Dr P Hunt. Hunt Research Group. www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk. Accessed 17/12/14.

- ↑ Plumley J. A., Evanseck J. D. J. Phys. Chem. A. Covalent and Ionic Nature of the Dative Bond and Account of Accurate Ammonia Borane Binding Enthalpies. 2007, 111 (51). DOI: 10.1021/jp074937z

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Shriver d., Atkins P. Inorganic Chemistry Oxford University Press. Great Britain. 5th ed. 2010.

- ↑ Clementi E., Raimondi D. L. J. Chem. Phys. Atomic Screening Constants from SCF Functions. 1963, 38 (11). DOI:10.1063/1.1733573