Rep:Mod:erty35plm

Part I

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

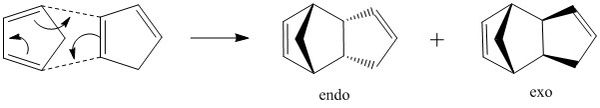

The dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is an example of Diels-Alder reaction. [1] The reaction proceeds to yield the two possible conformational products: the exo- and endo- conformers. Studies have shown that at ambient temperature, this reaction affords the endo- isomer exclusively and some exo- dimer is observed at high temperature (>150 °C).[2] This stereoselection can be explained by the Woodward-Hoffmann rules.[3]

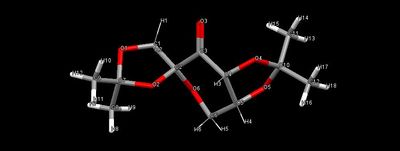

Structures of the endo- and exo- dimers were generated and optimised using Avogadro (MMFF94s). A comparison of the energies of the two dimers showed that the exo- product is thermodynamically more stable than the endo- product (55.4 kcal mol-1 < 58.2 kcal mol-1), and therefore is expected to be formed under thermodynamic conditions. However, the predominance of the endo- product suggests that dimerisation is irreversible in this case (as thermodynamic product would dominate if reaction is reversible), and proceeds via a kinetic pathway with lower energy transition state.

| Total Energy / kcal mol-1 | |

|---|---|

| Endo- | 58.2 |

| Exo- | 55.4 |

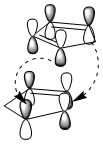

The diagram below illustrates the HOMOs and LUMOs interactions of both conformations. Secondary orbital interations (SOIs) [4] can be observed in the formation of endo- isomer, thereby stabilising the transition state, resulting in the quicker formation of kinetic endo- product. This SOI is not observed in the formation of exo- isomer.

Hydrogenation of Endo Dimer

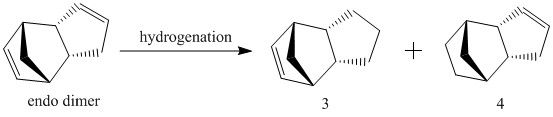

Similarly, the endo- isomer from dimerisation of cyclopentadiene undergoes hydrogenation under kinetic or thermodynamic control. This generates the dihydro derivatives 3 and 4 respectively.

Structures of the derivatives were optimised using Avogadro (MMFF94s) and a breakdown of energies associated with the products is shown below.

| Dihydro Derivative 3 | Dihydro Derivative 4 | Energy Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy / kcal mol-1 | 50.44569 | 41.25749 | 9.1882 |

| Total Bond Stretching Energy / kcal mol-1 | 3.31167 | 2.8231 | 0.48857 |

| Total Angle Bending Energy / kcal mol-1 | 31.93422 | 24.68555 | 7.24867 |

| Total Stretch Bending Energy / kcal mol-1 | -2.10217 | -1.65719 | -0.44498 |

| Total Torsional Energy / kcal mol-1 | -1.47039 | -0.37833 | -1.09206 |

| Total Out-of-plane Bending Energy / kcal mol-1 | 0.01304 | 0.00028 | 0.01276 |

| Total van der Waals Energy / kcal mol-1 | 13.63985 | 10.63705 | 3.0028 |

| Total Electrostatic Energy / kcal mol-1 | 5.11949 | 5.14702 | -0.02753 |

Both derivatives are of lower energy than the starting endo- dimer, suggesting that the hydrogenation reactions are exothermic processes. The calculated results indicate that 4 has a lower total energy, and is thus the predicted thermodynamic product. Hydrogenation of the double bond in the norbornene ring (yielding derivative 4), proceeds several times faster than that in the cyclopentene ring (yielding derivative 3). This can be explained by the difference in enthalpies of hydrogenation of the two C=C double bond.[5] Enthalpy of hydrogenation of the C=C double bond in norbornene is about 30 kJ mol -1 higher than that in the cyclopentene ring. Therefore, hydrogenation proceeds via a thermodynamic pathway. Upon observation of the energies breakdown, total angle bending energy and total van der Waals energy contributed mainly to this difference in energies between the two products. Angle bending energy increases as the angles are bent from their norm. 3 has a much higher angle bending energy than 4 due to the double bond present in the norbornene ring, resulting in significant ring strain. 3 has a high van der Waals energy than 4 too as hydrogenation in the cyclopentene ring results in stronger van der Waals repulsion between the hydrogens on sp3 carbons.

Stable Conformation of the Intermediate

Atropisomers [6] are stereoisomers arising from restricted rotation about single bonds such that steric strain energy barrier is high enough to allow conformers to be isolated as separate chemical species. The example studied here is the key intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol proposed by Paquette. [7] The intermediate will adopt a more stable conformation (with lower total energy). The two atropisomers illustrated below differ in the orientation of the carbonyl group. The bridgehead olefin group prevents hinders bond rotation and prevents interconversion between the conformers.

Energies of four conformers of each molecule are tabulated below. It can be observed from the results that chair conformation has the lowest energies for molecules (as highlighted). Twist boat has a much twisted structure, resulting in the high torsional energy.

| Intermediate 9 | Intermediate 10 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair (1) | Chair (2) | Twist Boat (1) | Twist Boat (2) | Chair (1) | Chair (2) | Twist Boat (1) | Twist Boat (2) | |

| Total Bond Stretching Energy / kcal mol-1 | 7.66398 | 7.50797 | 7.95038 | 7.63588 | 7.15053 | 7.05039 | 7.18447 | 7.13796 |

| Total Angle Bending Energy / kcal mol-1 | 28.25865 | 18.82943 | 29.49027 | 21.779 | 22.43356 | 19.85809 | 20.99908 | 20.88104 |

| Total Stretch Bending Energy / kcal mol-1 | -0.08533 | -0.15925 | 0.08039 | 0.04594 | -0.24148 | -0.40314 | -0.32717 | -0.3322 |

| Total Torsional Energy / kcal mol-1 | 0.31517 | 0.06803 | 2.77348 | 2.12829 | -1.93572 | -0.17676 | 3.88528 | 2.40238 |

| Total Out-of-plane Bending Energy / kcal mol-1 | 0.97446 | 0.96265 | 0.95332 | 1.00095 | 0.67144 | 0.69762 | 0.6609 | 0.68191 |

| Total Vander Waals Energy / kcal mol-1 | 33.11546 | 33.2439 | 34.72462 | 34.9075 | 32.12997 | 32.21822 | 33.94601 | 33.74448 |

| Total Electrostatic Energy / kcal mol-1 | 0.30307 | 0.26853 | 0.3161 | 0.27721 | 0.82755 | 0.80373 | 0.75517 | 0.76804 |

| Total Energy / kcal mol-1 | 70.54546 | 60.72126 | 76.28854 | 67.77476 | 61.03585 | 60.04815 | 67.10375 | 65.2836 |

The lowest energy conformer was obtained by adjusting the positions of the atoms manually. This was achieved by forming a chair conformation in the cyclohexane ring and maximising the number of C-H bonds which are in anti-periplanar geometry to the carbonyl group.

As seen from the tabulated results, 10 has a lower total energy, and is thus the predicted stable thermodynamic conformer. This can be rationalised by the almost anti-periplanar geometry of the carbonyl group and C-H bonds shown in the structure. This results in the interaction of σC-H/σ*C=O and σC-H/π*C=O, leading to stabilisation of the conformer. However, this interaction is not present in conformer 9, where the carbonyl group points upwards and is thus in the plane as the C-H bonds. This leads to an increase in the angle bending energy and the torsional energy, making 9 the less preferred conformer.

Hyperstable Olefin

In 1924, Julius Bredt proposed that it is impossible to have a double bond on the bridgehead of a bridged ring system. [8] This is because a bridgehead olefin is equivalent to having a trans double bond on the ring, and would result in a combination of ring and angle strain. However, this was later disputed by Prelog's study on the isolation of bicyclo[X.3.1] alkenones (where X ≥ 5). Recently, Maier and Scheyler introduced the term "hyperstable olefin", which is defined as one in which the olefin strain (OS) energy (total strain energy of the olefin - total strain energy of the parent hydrocarbon, both in the most stable conformations) has a negative value. [9] Atropisomer 10 is one example where it contains a hyperstable olefin. Total strain energy of the parent hydrocarbon of 10 was calculated in a similar way (MMFF94s in Avogadro). A comparison with that of the olefin reveals that the OS energy here is about -13 kcal mol-1. This shows that the polycycloalkane is has higher angle strain and is thus less stable than the corresponding olefin. This stability of the bridgehead olefin provides the rationale behind the its slow reactivity.

Moreover, from the MO perspective, a twisted olefin has a reduced π overlap, resulting in a decrease in the HOMO-LUMO energy gap. A HOMO-LUMO degeneracy is achieved when twist angle = 90°. As the OS energy value is directly correlated to the twisting angle strain of the olefin, a high OS value would suggest a low HOMO-LUMO energy gap and thus high chemical reactivity of the olefin. In this case, therefore, the negative OS value would suggest a low chemical reactivity at the olefin.

This section of the exercise involves the spectroscopic analysis of intermediate 17 and 18 in the synthesis of Taxol. As in the previous part, structures of intermediates were generated and optimised using Avogadro (MMFF94s), energies of the most stable conformations were tabulated below.

| Intermediate | Energy / kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|

| 17 | 117.96545 |

| 18 | 100.50615 |

1H and 13C NMR spectra were simulated with the following settings, and compared with the spectroscopic information reported in literature.

# B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Opt SCRF=(CPCM,Solvent=benzene*) Freq NMR EmpiricalDispersion=GD3

* Benzene was used as the solvent system so as to make a comparison with the literature data.

1H NMR Analysis

Generally, the simulated 1H NMR correlates well with the literature data apart from two regions. The peak corresponding to the olefin proton at δ 5.98 ppm has a large difference of 0.77 ppm from its literature value. If the peak at δ 0.64 ppm corresponds to that at δ 1.03 ppm, a difference of 0.39 ppm arises. A mismatch is multiplicities is observed too. This is due to the limitation of the calculations - the inability of the software to take bond rotation into consideration. For instance, the peaks from δ 2.70 - 3.00 ppm correspond to a multiplet of six hydrogens, whereas Gaussian has computed each shift individually.

| Calculated Data [10] | Literature Data [11] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Shift / ppm | Integral | Chemical Shift / ppm | Integral |

| 5.98 | 1 | 5.21 | 1 |

| 3.20 | 2 | 3.00 - 2.70 | 6 |

| 3.06 | 1 | ||

| 2.97 | 1 | ||

| 2.78 | 3 | ||

| 2.69 | 1 | 2.70-2.35 | 4 |

| 2.48 | 3 | ||

| 2.33 | 1 | 2.20-1.70 | 6 |

| 2.23 | 1 | ||

| 2.01 | 3 | ||

| 1.84 | 1 | ||

| 1.58 | 4 | 1.50-1.20 | 3 |

| 1.28 | 3 | 1.1 | 3 |

| 1.21 | 1 | 1.07 | 3 |

| 0.96 | 3 | 1.03 | 3 |

| 0.64 | 1 | ||

13C NMR Analysis

In general, the calculated 13C NMR spectrum agrees well with the literature data. 13C has a lower natural abundance than 1H and therefore no coupling was observed (as in the case of 1H NMR). This allows a clearer interpretation of the spectrum.

| Calculated Data [10] | Literature Data [11] | Difference / ppm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Shift / ppm | Integral | Chemical Shift / ppm | Integral | |

| 211.06 | 1 | 211.49 | 1 | -0.43 |

| 147.93 | 1 | 148.72 | 1 | -0.79 |

| 120.03 | 1 | 120.9 | 1 | -0.87 |

| 93.63 | 1 | 74.61 | 1 | 19.02 |

| 60.46 | 1 | 60.53 | 1 | -0.07 |

| 54.77 | 1 | 51.30 | 1 | 3.47 |

| 53.94 | 1 | 50.94 | 1 | 3.00 |

| 49.54 | 1 | 45.53 | 1 | 4.01 |

| 49.15 | 1 | 43.28 | 1 | 5.87 |

| 46.7 | 1 | 40.82 | 1 | 5.85 |

| 41.90 | 1 | 38.73 | 1 | 3.17 |

| 41.73 | 1 | 36.78 | 1 | 4.95 |

| 38.53 | 1 | 35.47 | 1 | 3.06 |

| 34.05 | 1 | 30.84 | 1 | 3.21 |

| 33.61 | 1 | 30 | 1 | 3.61 |

| 28.09 | 1 | 25.56 | 1 | 2.53 |

| 26.45 | 1 | 25.35 | 1 | 1.10 |

| 24.40 | 1 | 22.21 | 1 | 2.19 |

| 22.62 | 1 | 21.39 | 1 | 1.23 |

| 21.57 | 1 | 19.83 | 1 | 1.74 |

Distinct peaks include the deshielded carbons at chemical shifts δ 211 ppm, δ 147 ppm and δ 120 ppm (corresponding to the carbonyl carbon and the two olefin carbons respectively). The largest deviation occurs at δ 94 ppm (δ 75 ppm from literature) - experimental data are significantly more upfield (19 ppm) than the calculated value. This is because spin-orbit coupling was not taken into consideration in calculation, and correction factor should be accounted for to obtain more accurate data. The other two peaks with difference in chemical shifts > 5 ppm occur at δ 49 ppm and δ 47 ppm. This could be due to the slight difference in geometries of the molecules (further optimisation of energy of Intermediate 18).

Part II

Analysis of the crystal structures of Shi and Jacobsen Catalysts

Studies on the anomeric effect of Shi catalyst precursor

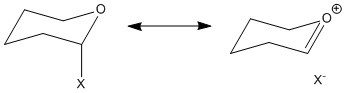

"Anomeric effect" refers to the steric and stereoelectronic effect that describes the preference of the polar group adjacent to the anomeric carbon to take up an axial position. In the case of the Shi catalyst precursor, "anomeric centres" refer to the carbon centres in the O-C-O substructures. The donation of nOsp3 → σ*C-O (app) results in the shortening of one C-O bond (partial double bond) and lengthening of the other C-O bond (as the lone pair is being donated into the anti-bonding σ* orbital). This is an example of "double bond-no bond resonance".

The catalyst precursor was built on the Conquest programme (Cambridge Crystal Database) and analysed using Mercury. By inspection, there are three anomeric centres in the molecule (i.e. O1-C9-O2, O2-C2-O6 and O4-C10-O5). However, from the calculated bond lengths (Table 7), O2-C2 and O6-C2 bonds are similar in lengths as compared to the other two anomeric centres, this suggests that O2-C2-O6 does not contain an anomeric centre. Anomeric effect is not expected here as the lone pair on O2 is unable to be in a anti-periplanar geometry to the C2-O6 bond (same applies to lone pair on O6 and O2-C2 bond).The slight difference in lengths of O2-C2 and O6-C2 bonds can be explained by the oxygen positions. O2 is in a 5-membered ring system while O6 is in a cyclohexane. As for the substructures containing anomeric centres, O1-C9 and O5-C10 are shortened (partial double bond character) while O2-C9 and O4-C10 are lengthened (donation into σ*C-O orbital).

| Bonds | Lengths |

|---|---|

| O2-C7 | 1.454 |

| O1-C7 | 1.423 |

| O6-C2 | 1.415 |

| O2-C2 | 1.423 |

| O4-C10 | 1.456 |

| O5-C10 | 1.428 |

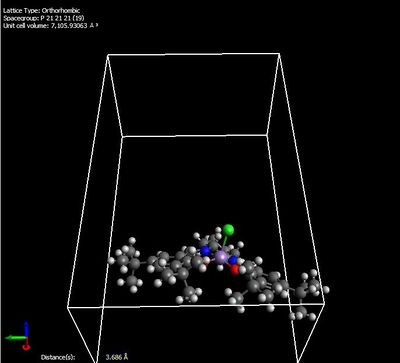

Studies on interactions of t-butyl groups on the rings of Jacobsen catalyst precursor

The catalyst precursor was built on the Conquest programme (CCDC) and analysed using Avogadro.

Intramolecular distance between the two t-butyl group was found to be 3.68645 Å, slightly longer than the sum of the van der Waals radii of two carbon atoms (3.40 Å). According to the Lennard-Jones potential curve, a distance longer than the van der Waals radii (equilibrium distance) suggests that the interaction between the t-butyl groups is attractive. This provides the rationale behind the Jacobsen catalysis mechanism shown below, and thus the predominance of cis-epoxide formation. This favourable attraction between the t-butyl groups means that alkene can only approach the catalyst in a certain orientation (alkene cannot attack from the face of t-butyl groups), thus the epoxide formed is predominantly in cis- geometry. It is also observed that this enantioselectivity is less favourable for smaller or bulkier groups substituents. Smaller groups (e.g. methyl) would mean that the intramolecular distance is large and thus, very weak attraction between the groups; bulky substituents would lead to steric interaction between the groups.

Spectroscopic Analysis of epoxides synthesised

1,2-Oxy- 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene

1H NMR Analysis

Generally, the 1H NMR spectrum calculated agrees well with the literature data (in the range of ±0.34 ppm). The results are tabulated below.

| Calculated Data [12] | Literature Data [13] | Difference / ppm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Shift / ppm | Degeneracy | Chemical Shift / ppm | Degeneracy | |

| 7.62 | 1 | 7.28 | 1 | 0.34 |

| 7.39 | 2 | 7.08 - 7.17 | 2 | 0.31 - 0.22 |

| 7.25 | 1 | 6.98 | 1 | 0.27 |

| 3.56 | 1 | 3.74 | 1 | -0.18 |

| 3.48 | 1 | 3.62 | 1 | -0.14 |

| 2.95 | 1 | 2.68 | 1 | 0.27 |

| 2.27 | 1 | 2.44 | 1 | -0.17 |

| 2.21 | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | -0.09 |

| 1.87 | 1 | 1.65 | 1 | 0.22 |

13C NMR Analysis

As expected, the 13C NMR spectrum generally agrees well with the literature data (mostly in the range of ±4.87 ppm). The two peaks with the largest deviations occur at 30.2 ppm and 29.1 ppm (difference of 5.8 ppm and 7.3 ppm from the literature values), corresponding to carbons of the cyclohexl ring not directly bonded to the oxygen atom. The experimentally determined results are more upfield than the calculated data due to possible software overestimation of the contributions of ring currents from the phenyl ring.

| Calculated Data [12] | Literature Data [13] | Difference / ppm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Shift / ppm | Degeneracy | Chemical shift / ppm | Degeneracy | |

| 135.4 | 1 | 136.7 | 1 | -1.3 |

| 130.4 | 1 | 132.6 | 1 | -2.2 |

| 126.7 | 1 | 129.5 | 1 | -2.8 |

| 123.8 | 1 | 128.4 | 1 | -4.6 |

| 123.5 | 1 | 128.4 | 1 | -4.9 |

| 121.7 | 1 | 126.1 | 1 | -4.4 |

| 52.8 | 1 | 55.1 | 1 | -2.3 |

| 52.2 | 1 | 52.7 | 1 | -0.5 |

| 30.2 | 1 | 24.4 | 1 | 5.8 |

| 29.1 | 1 | 21.8 | 1 | 7.3 |

Epoxidation of trans-ß-methyl styrene

1H NMR Analysis

Generally, the 1H NMR spectrum calculated agrees well with the literature data. The results are tabulated below. A mismatch in multiplicities is observed. This could be due to the in-built limitation of the software (as discussed previously). For example, the three hydrogens on the methyl group are in the same chemical environment due to bond rotation. Gaussian, however, has computed each shift individually. Similarly, literature reports the five aromatic hydrogens as to be in the same chemical environment, whereas this is not the case in Gaussian calculations.

| Calculated Data [14] | Literature Data [15] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Shift / ppm | Degeneracy | Chemical Shift / ppm | Degeneracy |

| 7.49 | 3 | 7.35 - 7.24 | 5 |

| 7.42 | 1 | ||

| 7.31 | 1 | ||

| 3.41 | 1 | 3.57 | 1 |

| 2.79 | 1 | 3.04 | 1 |

| 1.68 | 1 | 1.45 | 3 |

| 1.59 | 1 | ||

| 0.72 | 1 | ||

13C NMR Analysis

Generally, the 13C NMR spectrum correlates well with the literature data (mostly in the range of ±4.7 ppm). The two peaks with the largest deviations occur at δ 60.6 ppm and δ 18.8 ppm (difference of 5.4 ppm and 6.2 ppm from the literature values), corresponding to carbon directly bonded to the oxygen and the methyl carbon respectively.. The experimentally determined results are more upfield than the calculated data due to possible software overestimation of the contributions of ring currents from the phenyl ring.

| Calculated Data [14] | Literature Data [15] | Difference / ppm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Shift / ppm | Degeneracy | Chemical Shift / ppm | Degeneracy | |

| 135.0 | 1 | 135.6 | 1 | -0.6 |

| 124.1 | 1 | 128.1 | 1 | -4.0 |

| 123.3 | 1 | 127.5 | 1 | -4.2 |

| 122.8 | 1 | 126.6 | 1 | -3.8 |

| 122.7 | 1 | 125.4 | 1 | -2.7 |

| 118.5 | 1 | 120.8 | 1 | -2.3 |

| 62.3 | 1 | 57.6 | 1 | 4.7 |

| 60.6 | 1 | 55.2 | 1 | 5.4 |

| 18.8 | 1 | 12.6 | 1 | 6.2 |

Chiroptical Properties Analysis

Optical rotation of epoxides enantiomers was calculated from the quantum-mechanical optimised NMR output (MMFF94s, Avogadro) with the following settings at 589 nm and 365 nm. No literature data was reported for optical rotation at 365 nm, therefore these simulated data are not tabulated below. Chloroform was used as the solvent system to enable a meaningful comparison with literature data.

# CAM-B3LYP/6-311++g(2df,p) polar(optrot) scrf(cpcm,solvent=chloroform) CPHF=RdFreq

| Epoxide | Optical Rotation / ° | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated Value | Literature Data | Difference | |

| (1S,2R)-1,2-Oxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene | -35.86 [16] | -38.8 [17] | 2.94 |

| (1R,2S)-1,2-Oxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene | -155.82 [18] | -144.9 [19] | -10.92 |

| (1R,2R)-trans-ß-methylstyrene oxide | 46.77 [20] | 47.8 [21] | -1.03 |

| (1S,2S)-trans--ß-methylstyrene oxide | -46.77 [22] | -46.9 [23] | 0.13 |

Generally, the calculated values agree well with literature. (1R,2S)-1,2-Oxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene has a value that deviates more (as compared to the other molecules) from the literature. However, optical rotation is known to be unreliable. Several values were found in the literature and they vary with temperature, solvent and concentration. Further studies could be carry out to study the effect of varying wavelengths of irradiation on optical rotation.

Studies on the Transition States of epoxidation of ß-methyl styrene

The lowest energy transition states were identified by calculating the total energy for each system as corrected for entropy and zero-point thermal energies. The results were tabulated below, with the lowest energy transition states highlighted.

Shi epoxidation

By inspection, R,R (4) and S,S (4) have the lowest energy transition states, giving a difference in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of 20.219 kJ mol-1. Applying formula (1) and (2) gives an enantiomeric excess of 99.94% in favour of R,R epoxide. This is slightly higher than the literature value of 95.5%, [23] though still in good agreement. This shows that Shi catalyst is highly enantioselective in the epoxidation of asymmetric alkenes.

| Transition States | Total Energy / Ha | Total Energy / kJ mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| R,R (1) | -1343.02297 | -3526107.076 |

| R,R (2) | -1343.019233 | -3526097.265 |

| R,R (3) | -1343.029272 | -3526123.622 |

| R,R (4) | -1343.032443 | -3526131.948 |

| S,S (1) | -1343.017942 | -3526093.875 |

| S,S (2) | -1343.015603 | -3526087.734 |

| S,S (3) | -1343.023766 | -3526109.166 |

| S,S (4) | -1343.024742 | -3526111.729 |

Jacobsen epoxidation

cis-ß-methyl styrene

Similarly, the enantiomeric excess of cis-ß-methyl styrene epoxidation by Jacobsen catalyst can be calculated using formula (1) and (2), giving a value of ee (%) = 99.98% in favour of S,R epoxide. This is slightly higher than the literature data of 92%, [24] though still in good agreement.

| Transition State | Total Energy / Ha | Total Energy / kJ mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| S,R (1) | -3383.259559 | -8882748.649 |

| S,R (2) | -3383.253442 | -8882732.589 |

| R,S (1) | -3383.25106 | -8882726.335 |

| R,S (2) | -3383.25027 | -8882724.261 |

trans-ß-methyl styrene

Finally, the enantiomeric excess of trans-ß-methyl styrene epoxidation by Jacobsen catalyst was calculated in a similar manner, giving a result of ee (%) = 99.96% in favour of S,S epoxide. No literature data was found and thus no comparison can be made.

| Transition State | Total Energy / Ha | Total Energy / kJ mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| S,S (1) | -3383.262481 | -8882756.321 |

| S,S (2) | -3383.257847 | -8882744.154 |

| R,R (1) | -3383.253816 | -8882733.571 |

| R,R (2) | -3383.254344 | -8882734.957 |

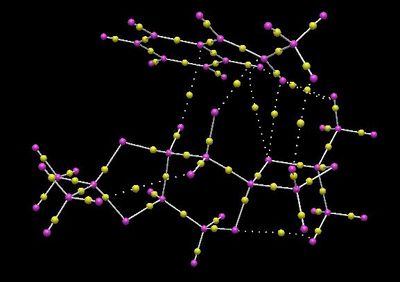

Investigation of Non-covalent Interactions in the Active-sites of Reaction Transition State

Non-covalent interactions (NCI) refer to the electromagnetic interactions between and/or within molecules. Generally, it can be classified into four categories, namely van der Waals forces, electrostatic, π-effects and hydrophobic effects. Studies on the NCI in the active-sites of reaction transition state allows a more thorough investigation of the catalytic activities and mechanisms of the reaction. The transition state chosen here is the reaction between trans-ß-methylstyrene and Shi catalyst. The electron density of the transition state is generated by GaussView.

The abundance of attraction in the model shows the transition state is stabilised. The alkene undergoes a spiro transition state [25] with favourable NCI interactions, shown by the green regions. This mode of transition state is electronically preferred over planar mode of attack as a result of stabilising interaction between the lone pair on the dioxirane oxygen and the π* orbital of the alkene. However, the planar transition state is favoured for trisubstituted alkenes due to steric effects.

The multi-coloured ring in the middle of the structure indicates the formation of a bond - comprising of both covalent and non-covalent interactions. Many NCI interactions are observed in the model. This includes the hydrogen bonding between the oxygen lone pair on the catalyst and the hydrogens on the alkene; as well as the attractive interaction between the oxygen lone pair and the aromatic ring, which could be rationalised by the lone pair-π interactions (dispersion forces and dipole-induced dipole interactions). [26]

Investigation of Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the Active-site of the Reaction Transition State

The QTAIM analysis provides further insights into the non-covalent interactions in the transition state. The electronic topology was generated using Avogadro2.

The bond critical point (BCP) is defined as a point along the bond path at the interatomic surface where the shared electron density reaches a minimum. These points are represented by the yellow dots in between the pink atoms. The dotted lines represent non-covalent interactions between atoms, and it therefore makes sense that these lines coincide with the green and blue regions in the NCI model discussed in the previous section. For example, dotted lines are observed between oxygen and hydrogen atoms, corresponding to hydrogen bondings which help to stabilise the transition state (discussed previously). It is also interesting to note that there is only one BCP connecting the dioxirane oxygen and the carbon atom in alkene, suggesting that the mechanism of this catalytic reaction is not concerted.

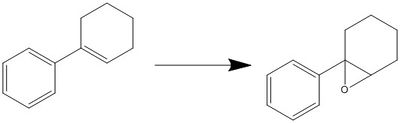

Suggestion of new candidates for investigation

Phenyl cyclohexene is an interesting molecule that undergoes epoxidation to form 1-phenyl-1-cyclohexene oxide. [27] It has a six-membered ring, which would result in different conformers during the reaction. The most stable transition state thus has to be modelled and studied using the techniques discussed in this assignment. Enantioselectivities of the catalysts can be studied with this molecule.

This epoxidation reaction has been reported to have good yield. The optical rotatory power reported has a range of about 30° and it varies with concentration. Further investigation could be carried out to study the effect of concentration on the optical rotatory power.

Reference

- ↑ P. Caramella, P. Quadrelli and L. Toma, "An Unexpected Bispericyclic Transition Structure Leading to 4+2 and 2+4 Cycloadducts in the Endo Dimerization of Cyclopentadiene", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124 (7), 1130–1131.DOI:10.1021/ja016622h

- ↑ W. L. Jorgensen, D. Lim, J. F. Blake, "Ab initio study of Diels-Alder reactions of cyclopentadiene with ethylene, isoprene, cyclopentadiene, acrylonitrile, and methyl vinyl ketone", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1993, 115 (7), 2936–2942.DOI:10.1021/ja00060a048

- ↑ G. Paul, T. L. Alejandro, K. P. Chattaraj, D. P. Frank, "The Woodward–Hoffmann Rules Reinterpreted by Conceptual Density Functional Theory", Accounts of Chemical Research 45, (5), 683–95.DOI:10.1021/ar200192t

- ↑ J. I. García, J. A. Mayoral, and L. Salvatella, "Do Secondary Orbital Interactions Really Exist?", Acc. Chem. Res., 2000, 33 (10), 658–664. DOI:10.1021/ar0000152

- ↑ M.Hao, B. Yang, H. Wang, G. Liu, and S. Qi "Kinetics of Liquid Phase Catalytic Hydrogenation of Dicyclopentadiene over Pd/C Catalyst", J. Phys. Chem. A, 2010, 114 (11), 3811–3817.DOI:10.1021/jp9060363

- ↑ J. G. Vinter and H. M. R. Hoffman, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1974, 96, 5466–5478. DOI:10.1021/ja00824a025

- ↑ L. A. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. "Rogers,[3.3] Sigmatropy within 1-vinyl-2-alkenyl-7,7-dimethyl-exo-norbornan-2-ols. The first atropselective oxyanionic Cope rearrangement", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112 (1), 277–283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ G. L. Buchanan, N. B. Kean, R. Taylor, "Bredt's rule: an anomalous decarboxylation", J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun., 1972, 201-202.DOI:10.1039/C39720000201

- ↑ A. B. McEwen, P. V. R. Schleyer, "Hyperstable olefins: further calculational explorations and predictions", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1986, 108 (14), 3951–3960.DOI:10.1021/ja00274a016

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 M. Liu, Gaussian Job Archive C20H30O1S2, 2014DOI:10042/27544

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 L. A. Paquette, K. D. Combrink, S. W. Elmore, R. D. Rogers, "Impact of substituent modifications on the atropselectivity characteristics of an anionic oxy-Cope ring expansion", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113 (4), 1335–1344.DOI:10.1021/ja00004a040

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 M. Liu, Gaussian Job ArchiveC10H10O1, 2014DOI:10042/27543

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 K. Smith, C. Liu and G. A. El-Hiti "A novel supported Katsuki-type (salen)Mn complex for asymmetric epoxidation", Org. Biomol. Chem., 2006, 004, 917-927.DOI:10.1039/B517611P

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 M. Liu, Gaussian Job ArchiveC9H10O1, 2014DOI:10042/27542

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Y. Kon, H. Hachiya, Y. Ono, T. Matsumoto, K. Sato "SAn Effective Synthesis of Acid-Sensitive Epoxides via Oxidation of Terpenes and Styrenes Using Hydrogen Peroxide under Organic Solvent-Free Conditions", Synthesis, 2011, 7, 1092 - 1098.DOI:10.1055/s-0030-1258467

- ↑ M. Liu, Gaussian Job ArchiveC9H10O1, 2014DOI:10042/27539

- ↑ S. Yian, Catalytic asymmetric epoxidation, 2002.

- ↑ M. Liu, Gaussian Job ArchiveC9H10O1, 2014DOI:10042/27538

- ↑ H. Irie, K. Sasaki, Tetrahedron, 1994, 50 (41), 11827 - 11838.

- ↑ M. Liu, Gaussian Job ArchiveC10H10O1, 2014DOI:10042/27540

- ↑ F. Fischer "Konfigurative Zuordnung über sterisch definierte Epoxydringe, III. Die hydrolytische Spaltung der optisch aktiven cis- und trans- 1-Phenyl-2-methyl-äthylenoxyde", Chemische Berichte, 1961, 94 (4), 893–901.DOI:10.1002/cber.19610940405

- ↑ M. Liu, Gaussian Job ArchiveC10H10O1, 2014DOI:10042/27541

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Z. Wang, Y. Tu, M. Frohn, J. Zhang, and Y. Shi, "An Efficient Catalytic Asymmetric Epoxidation Method", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119 (46), 11224–11235.DOI:10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ E. N. Jacobsen, W. Zhang, A. R. Muci, J. R. Ecker, L. Deng "Highly enantioselective epoxidation catalysts derived from 1,2-diaminocyclohexane", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113 (18), 7063–7064.DOI:10.1021/ja00018a068

- ↑ M. Hickey, D. Goeddel, Z. Crane, and Y. Shi "Highly enantioselective epoxidation of styrenes: Implication of an electronic effect on the competition between spiro and planar transition states", Protein Sci, 2009, 18(3), 595-605.DOI:10.1002/pro.67

- ↑ A. Jain, V. Ramanathan, R. Sankararamakrishnan, "Lone pair ... pi interactions between water oxygens and aromatic residues: quantum chemical studies based on high-resolution protein structures and model compounds", ''PNAS, '2004, '11 (16).DOI:10.1073/pnas.0307548101

- ↑ O. A. Wong and Y. Shi, "Organocatalytic Oxidation. Asymmetric Epoxidation of Olefins Catalyzed by Chiral Ketones and Iminium Salts", Chem. Rev, 2008, 108, 3958–3987.DOI:10.1021/cr068367v