Rep:Mod:eo308mod2

Third Year Computational Laboratory - Module 2: Bonding (Ab initio and density functional molecule orbital)- Emma Oakton (eo308, CID:00557791)

Structural analysis of TlBr3

Optimising the TlBr3 ground state structure

In calculating the optimised structure of a molecule, we are in turn finding the molecular structure at equilibrium. The starting point of the calculation is an initial structure which is an estimate of the equilibrium structure. The potential energy of this structure is found by solving the Schrödinger equation for the involved electrons, in this calculation we assume the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. The structure is then altering the relative positions of the nuclei systematically. The potential energy is then re-calculated for this structure. If the energy of the altered structure is lower than that of the initial structure, the calculation continues by making further alterations to that structure. Therefore the change in potential energy (ΔPE) with respect to change in nuclear position (ΔR) is calculated, this is the first derivative of the potential energy – nuclear position relationship (Potential Energy Surface - PES).

The process continues until any further alteration of the molecular structure results in no change in potential energy, i.e. a potential energy plateau point has been reached. This is noted when the ΔPE/ΔR value is zero. The structure at ΔPE/ΔR=0 is the optimised structure.

To commence the structural analysis of TlBr3, it's geometry must first be optimised. This process calculates the optimum structure, corresponding to that with the lowest energy.

Process

Firstly, using Gaussview 3, a model of TlBr3 was drawn with initial bond lengths of 2.69Å. The point group was then restricted to D3h and the tolerance to this fact set as 'Very tight'. This very low tolerance means there will be little deviation from the D3h point group for the optimised molecule, leading to more accurate molecular orbitals and vibration, which will be calculated later.

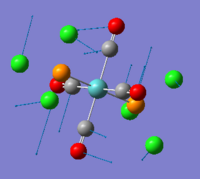

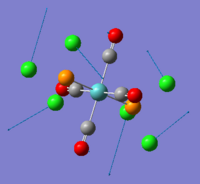

An optimisation calculation was then run on the initial TlBr3 structure (using Gaussview 3). Clicking the button below will show figure 1, a Jmol of the initial TlBr3 structure and figure 1 (below right) shows the data provided by the results summary, once the calculation was completed.

Figure 1

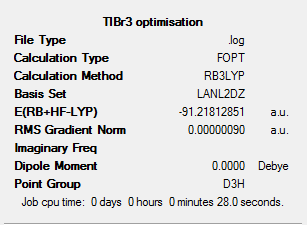

Figure 2 left gives information on the calculation method along with the results. From this we can see the calculation method was RB3LYP and the basis set used LANL2DZ.

The method used (noted as RB3LYP) was a DFT-B3LYP method which uses Density Functional Theory.

LanL2DZ is the pseudo potential used in this calculation, a pseudo potential is a function used which models the non valence electrons in an atom. Tl and Br are both considered heavy elements with many electrons. Because of this, using the Schrodinger equation with a high accuracy basis set would not accurately represent interactions between these heavy molecules. We assume here that the bonding interactions in molecules are a result of interaction of valence electrons. Therefore using this the electron models of Br and Tl can be simplified by using a pseudo potential. The pseudo potential is used to model the non valence electrons, which a basis set is used to model the valence electrons.

From the data in figure 2 we can also note the energy and dipole moment of the optimised structure, these can be found in table 1 below. It is noted, a calculation error of ±0.0038 au (Hartrees) was included for the energy value and the dipole moment value is accurate to 2 decimal places.

| Molecule | TlBr3 optimised structure |

|---|---|

| Energy [E(RB+HF-LYP) / au (Hartrees) | -91.22±0.0038 |

| Dipole Moment / Debye | 0.00 |

The optimised structure can be checked (to show the calculation converged to a minimum) by looking at the output log file of the calculation, a section of which can be seen in figure 3.

The above figure shows that all bond length and bond angle values for the structure converged to the same value, suggesting the calculation was completed successfully. From this we can say our structure represents an energy minimum and is equivalent to the equilibrium structure of TlBr3. The button below, links to a Jmol of the optimised TlBr3 structure.

The bond lengths and bond angles of the optimised structure were then calculated from Gaussview 3. This is shown below, it was noted all bond lengths and bond angles in the molecule were equal.

| Molecule | TlBr3 optimised structure |

|---|---|

| Tl-Br Bond length / Å | 2.65±0.01 |

| Br-Tl-Br Bond angle / oC | 120.0±0.1 |

The completed output log file for this calculation can be found at: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/6/6e/TlBr3_structure_optimisation_output_log_file.LOG

Frequency analysis of TlBr3

Optimisation does not ensure us that the structure calculated is the potential energy minimum. This is because the first derivative of a function (as used during optimisation) only tells us the gradient of the potential energy slope. This could be zero for both energy minima and maxima. Therefore during the frequency analysis provides us with the second derivative of the potential energy surface. If the calculated frequencies for the structure are positive, then that molecular structure corresponds to the PE minimum and therefore is the equilibrium structure. If this is not the case, the structure corresponds to a transition state and is a potential energy maximum.

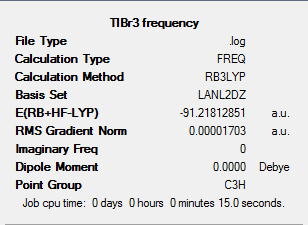

Frequency analysis was then completed on TlBr3. The same method (DFT-B3LYP) and basis set (LANL2DZ) were used for the calculation.

The output file for this frequency analysis can be found at: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/c/ca/TLBR3_FREQUENCY.LOG

The result summary of the frequency analysis can be found in figure 4 below. Figure 5 shows the output file showing the frequency results.

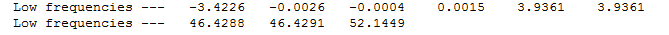

Figure 6 shows the low frequency vibrations that have been calculated for TlBr3. Although some of these are shown as negative, they are extremely close to zero they are not considered as true negative values. This is because Gaussian optimises these values to zero and as a result, some very small negative values are achieved.

The lowest real mode can be found by animating the vibrations. The list of IR vibrations can be found below.

The figure (left) shows that the lowest real mode occurs at 46.4cm-1. An animation and explanation of this mode and description of the movement can be found below.

Tl-Br bond length in TlBr3

The table below shows the Tl-Br bond distance as calculated above and reported in literature[1].

| Molecule | TlBr3 optimised structure |

|---|---|

| Tl-Br Bond Length / | 2.65±0.01 |

| Literature Tl-Br Bond Length / | 2.62-2.63 |

The above table shows that the calculated Tl-Br bond length is is good accordance with the literature value. Therefore it can be said that the optimisation has been completed successfully (also shown by frequency analysis) and the bond length produced is reasonable.

Note: Bonds in Gaussview 3

It was noted during the exercises completed that for some structures, Gaussview 3 did not show bonds between atoms for the optimised structures. This is because Gaussview has a set threshold atomic-distance at which a bond will be recognised. If the optimised bond distance is more than the threshold, Gaussview will not visualise a bond between those atoms, however if the bodn distance is less than the threshold value, a bond will be recognised. As most of these are set from organic molecules, usually bonds are missed in inorganic compounds such as those investigated here.

A bond can be loosely described as an attraction between two atoms which keeps them held a certain distance from one and other, this distance is noted as the bond length. More specifically, this attraction can be a result of dipole attraction between two oppositely charged species, termed an ionic bond, or the attraction between electrons and nuclei, termed a covalent bond. In both cases e;electromagnetic forces cause this attraction. Ionic and covalent bonds are considered strong, as their presence results is relatively short bond distances. However there are also bonds which have a longer range such as Hydrogen bonds, which result from dipole-dipole attractions.

Therefore it can be said that just because Gaussview does not visualise a bond (because the bond distance is too large) this does not mean there is not a bond present.

The MO of BH3

In this section, the molecular orbitals of BH3 will be calculated. Firstly the geometry of an inital BH3 molecule was optimised, using Gaussian with a DFT-B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set. Figure 7 below shows the optimised structure of BH3 and the results summary for the optimisation. The output log file for this calculation can be found at the following site:https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/3/34/BH3_optimisation_output.LOG

The bond lengths and bond angles of the optimised structure were as follows in the table below.

| Molecule | BH3 optimised structure |

|---|---|

| B-H Bond length / Å | 1.19±0.01 |

| H-B-H Bond angle / oC | 120.0±0.1 |

As the structure is trigonal planar, the calculated bond angle agrees with what we would expect for a trigonal planar structure. The B-H calculated bond length agrees with the terminal B-H bond length in bis(trifluorophosphine)diborane(4) (1.252Å) in the following report[2]. This shows the BH3 structure has been optimised to reasonable accuracy.

Frequency analysis was then completed to confirm this optimised structure was indeed an energy minimum. The output file for this calculation can be found at: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/b/bc/EMMAOAKTON_BH3_FREQ.LOG

This output confirmed the structure gained through optimisation is the equilibrium BH3 structure. Table 6 below demonstrates the different vibrational modes calculated for BH3.

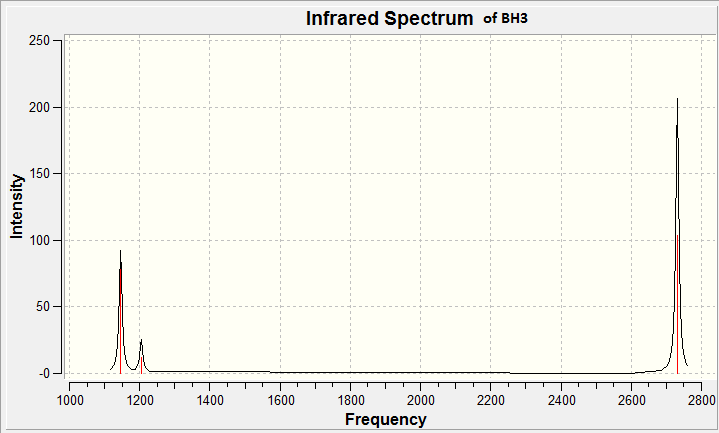

The frequency analysis also produced the infrared spectrum of BH3 this can be found in figure 8 below.

Figure 8 above shows that there are only 3 peaks seen in the IR spectrum of BH3, however table 5 above shows there are 6 vibrational modes. By comparing figure 8 with the data in table 5, we can deduce that the peak at 2593cm-1 is not seen. This can be rationalised by looking at the pictorial representation of the vibrational mode (4) and it's vibrational intensity. We see the vibrational intensity is zero, this is why a peak for this vibration is not seen. However justification for a vibrational intensity of zero can be taken from it's vibrational action. It is noted that the H atoms for vibrational mode 4 move in a concerted fashion and therefore this motion does not change the overall dipole of the molecule. In IR spectroscopy, only vibrations which result in a change of dipole within the molecule are recognised and because of this, vibrational mode 4 (occurring at 2593cm-1) is not seen in the spectrum.

It is also noted that 2 pairs of vibrations have the same vibrational frequency (modes 2,3 and 5,6). These vibrations are degenerate and therefore are only represented by one peak per pair in the spectrum.

Calculating the Molecular Orbitals of BH3

In this section, the MO's of BH3 will be calculated and compared to those produced by LCAO (Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals). The results from these two approaches can be compared and the accuracy of the qualitative approach (LCAO) can be determined.

The MO's of BH3 were calculated using Gaussian. A DFT-B3LYP method and 6-31G basis set were used for this calculation. The output files for this calculation can be found here: DOI:10042/to-5727

An MO diagram for BH3 was produced using LCAO and MO theory. The full diagram be can found at: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/0/0e/BH3_MO_diagram.png

Table 7 below shows pictures of the MO's calculated using Gaussian and those deduced using LCAO.

| MO number | LCAO | Gaussian | MO number | LCAO | Gaussian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

5 |

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

6 |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

7 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

8 |

|

|

From table 7, it can be seen the quantitative (Gaussian) and qualitative (LCAO) are in good agreement for MOs 1-6. When comparing the diagrams for each MO, the change in phase and orbital distribution correlate well. This shows at these levels, the LCAO approach is a good way to estimate the appearance of molecular orbitals. Some differences can be seen for MOs 7 and 8 in the extent of distribution over the molecule. The orbitals have greater spread covering the majority of the molecular area. this spread out distribution is not predicted so strongly with the LCAO orbitals.

The above investigation has shown LCAO to be a good and accurate technique for predicting the phase changes in an MO. However this investigation has also shown that the MO coverage of the molecule is much wider than that expected by LCAO. In conclusion LCAO is taken to be a useful theory to understand bonding and the bonding and anti-bonding interactions within molecular orbitals. However LCAO is a qualitative theory and therefore the accuracy is not sufficient to make any further justifications.

NBO Analysis

NBO analysis was also completed for the BH3 structure. The out put files for this calculation can be found along with the MO analysis output files here: DOI:10042/to-5727 .

The figure below shows the results of this:

This figure shows the charge separation within the BH,sub>3 molecule. This fits with what we would expect, B as a well known lewis acceptor has the most positive character, with a charge of 0.097. The H atoms have a more electron dense charge of -0.032. From this we can justify the neutral character of the BH3 molecule. The charges of the 3H atoms balance with the positive charge of the single B atoms. There is a residual charge of 0.001 however this discrepancy can be justified by calculation errors.

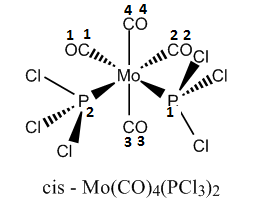

Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

In this section, the cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 will be investigated. By optimising the structure of these isomers and completing frequency analysis, we can investigate the relative thermal stabilities, vibrational modes and infra-red spectra of the two isomers.

Cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Geometry Optimisation

As seen previously, in order to compute further calculations for a structure, it;'s geometry must first be optimised to the equilibrium structure. This was completed as a two-stage process for the cis isomer. The initial structure was optimised, using the DFT-B3LYP method and relatively low-level basis set (LAN2MB). A loose convergence was set for the calculation. This produced a rough initial optimised geometry, the output file for which can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5798

The output geometry from the previous calculation was then altered, to a known starting point which will further ensure the correct potential energy minimum structure is found. The geometry which the initial optimised structure was altered to can be found below. A more accurate calculation was then completed. For this a LANL2DZ basis set was used, increasing the accuracy of the calculation. The amount of required convergence was also increased by using: int-ultrafine scf=conver=9 in the additional keywords section when setting up the calculation. The full results of this calculation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5797

Figure 10 below shows the geometry the structure was altered to further increase the accuracy of the optimisation. Figure 10 also found below, shows the final accurately optimised structure of cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2.

From this optimised structure (figure 10), the following data was collected.

| Molecule | Cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 fully optimised structure | Literature[3] Cis-Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 |

|---|---|---|

| P-Cl Bond length / Å | 2.24±0.01 | - |

| Mo-P Bond length / Å | 2.51±0.01 | 2.576, 2.577 |

| Axial Mo-C Bond length / Å | 2.06±0.1 | 2.059, 2.022 |

| Equatorial Mo-C Bond length / Å | 2.01±0.1 | 1.972, 1.973 |

| Axial CO Bond length / Å | 1.17±0.1 | 1.136, 1.137 |

| Equatorial CO Bond length / Å | 1.18±0.1 | 1.158, 1.149 |

| Molecule | Cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 fully optimised structure | Literature[3] Cis-Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 |

|---|---|---|

| P-Mo-P Bond Angle / o | 94.2 | 104.67 |

| P1-Mo-C1,2 Bond Angle / o | 176.1, 89.4 | 163.7, 80.6 |

| P1-Mo-C3,4 Bond Angle / o | 91.9, 89.2 | 94.0, 90.3 |

| P2-Mo-C1,2 Bond Angle / o | 89.4, 176.1 | 91.7, 173.2 |

| P2-Mo-C3,4 Bond Angle / o | 89.2, 91.9 | 90.6, 84.0 |

| C1-Mo-C2 Bond Angle / o | 87.1 | 83 |

| C1-Mo-C3,4 Bond Angle / o | 89.7, 89.1 | 87.0, 90.1 |

| C2-Mo-C3,4 Bond Angle / o | 89.1, 89.7 | 93.4, 91.3 |

| C3-Mo-C4 Bond Angle / o | 178.4 | 174.1 |

| Mo-C1,2,3,4-O1,2,3,4 Bond Angle / o | 177.8, 177.8, 177.9, 177.9 | 170.0, 176.6, 176.9, 177.5 |

Frequency Analysis

Frequency analysis of the cis isomer was next conducted. The DFT-B3LYP method and LANL2DZ basis set was used for this calculation. The output files for this can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5745 . It can be seen from the output log file that all generated low frequencies are non negative (>-5cm-1). This shows the optimised structure is the equilibrium structure of the isomer.

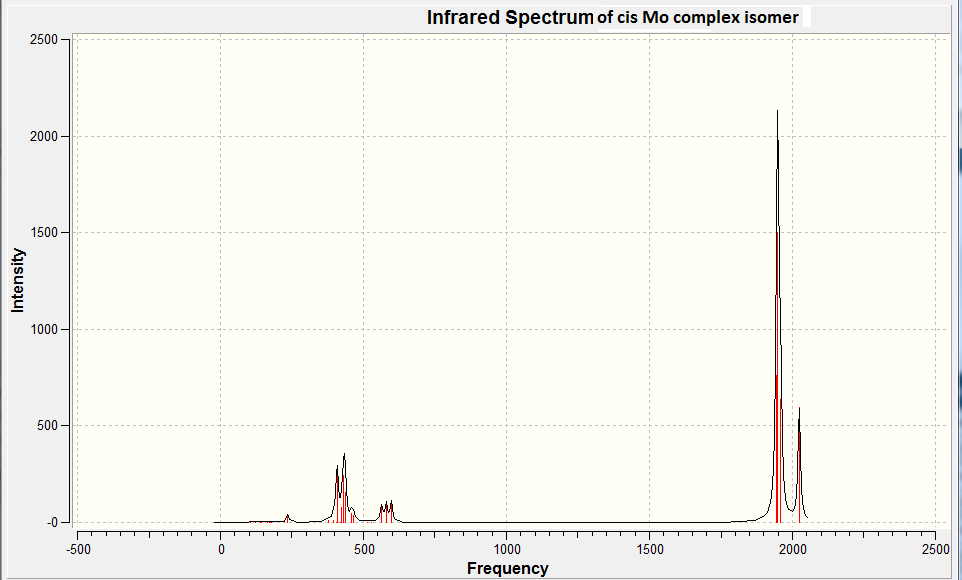

The computed IR spectrum of Cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 can be found as figure 11 below.

Trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

As for the cis isomer, the geometry of trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 was first optimised in a two-stage process. The first stage calculation used a DFT-B3LYP method and LAN2MB basis set, the convergence of the calculation was set as loose. The results for this rough primary optimisation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5746

It was noted that a good starting geometry for the second (more accurate) optimisation, would be the conformation for which the two PCl3 groups are eclipsed. The received output file from the first optimisation was checked and did indeed show this stereochemistry. Therefore the structure was then submitted for further optimisation. This was completed again using the DFT-B3LYP method. However the accuracy of the basis set was increased by using a LANL2DZ basis set. The output files for this calculation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5747

The jmol below shows the accurately optimised structure of trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2.

The table below shows the bond lengths calculated for this isomer.

| Molecule | Trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 fully optimised structure | Literature[4] Trans-Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 |

|---|---|---|

| P-Cl Bond length / Å | 2.24±0.01 | - |

| Mo-P Bond length / Å | 2.44±0.01 | 2.500 |

| Equatorial Mo-C Bond length / Å | 2.06±0.1 | 2.005, 2.016 |

| CO Bond length / Å | 1.17±0.1 | 1.164, 1.165 |

| Molecule | Trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 fully optimised structure | Literature[4] Trans-Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 |

|---|---|---|

| P-Mo-P Bond Angle / o | 177.4 | 180.0 |

| P1-Mo-C1,2,3,4 Bond Angle / o | 90.0, 91.3, 90.0, 88.7 | 87.2, 92.0 |

| P2-Mo-C1,2,3,4 Bond Angle / o | 90.0, 91.3, 90.0, 88.7 | - |

| C1-Mo-C2,3,4 Bond Angle / o | 89.5, 179.0, 90.5 | 92.1, 180.0 |

| C2-Mo-C3,4 Bond Angle / o | 89.5, 180 | 92.1, 180.0 |

| C3-Mo-C4 Bond Angle / o | 90.5 | - |

| Mo-C1,2,3,4-O1,2,3,4 Bond Angle / o | 179.2, 180.0, 179.2, 180.0 | - |

Frequency analysis

Frequency analysis was next conducted on the structure shown in figure 12. The DFT-B3LYP method and LANL2DZ basis set were used. The output files for the optimisation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5750 The output log file shows all calculated 'low frequencies' are non-negative values (>-5cm-1) and therefore the structure seen as figure 12 is confirmed as the equilibrium structure of the trans isomer.

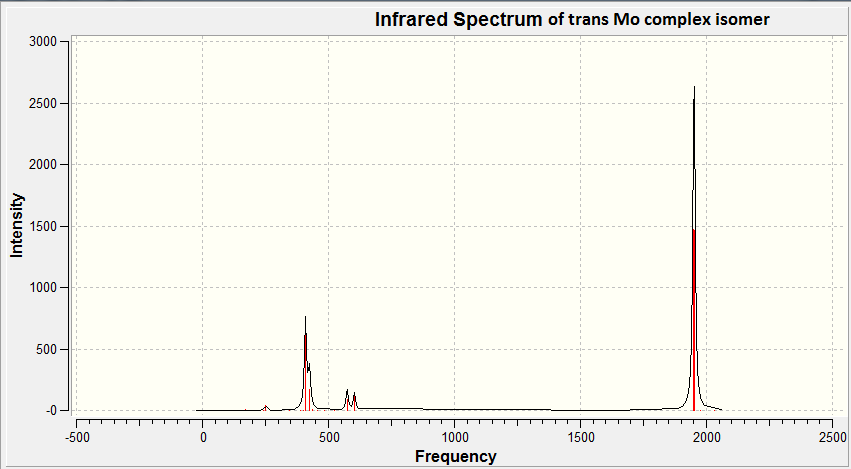

The IR spectrum of trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 can be found below.

Comparison between cis and trans geometries

From the tables above it can be seen the P-Cl bond lengths are the same in both species. However the Mo-P bond length is recorded as longer in the cis complex,in comparison to the trans. Differences are also seen between the Mo-C bond lengths and CO bond lengths.

It is noted that in the cis complex, the Mo-C bond lengths varys according to whether to C is axial or equatorial. This is due to the trans effect as in the cis isomer, the equatorial CO ligands are both trans the PCl3 groups. The P atom backbonds to the Mo centre by transferring electron density back into Mo d-orbitals. This increases the electron density on Mo and therefore strengthens the Mo-C bond which lies trans to the PCl3 group. The difference in bond length between the equatorial and axial Mo-C bonds is calculated as 0.05Å, suggesting a small trans effect is seen, however a larger difference in bond length would be seen with stronger back-bonding ligands such as CN-. In contrast, a trans effect is not seen for the trans complex, as non of the CO ligands are trans to the back-bonding PCl3. Because all the the CO groups have the same relationship to both PCl3 groups, all Mo-C bond lengths are the same.

A similar relationship is seen for the axial and equatorial CO bond lengths in the cis isomer. The axial CO groups have a shorter bond length in comparison to the equatorial CO group, therefore it can be said that the axial CO groups have a stronger CO bond. This could be justified again using the trans effect, the increase in strength of the Mo-C bonds for the equatorial C atoms, causes a small increase (0.01Å) in the CO bond length.

Both optimised cis and trans Mo complex geometries show good agreement with literature values.

Comparison between cis and trans energies

The energies of the difference isomers were taken from the results summary for the frequency analysis. These are reported in both Hartrees (au) and kJ/mol.

| Molecule | Energy accounting for accuracy of calculation / kJ/mol | Energy / Hartrees | Energy / kJ/mol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | -1.64x106 | -623.57707150 | -1.637259x106 |

| Trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | -1.64x106 | -623.57603112 | -1.637256x106 |

The above table shows, when accounting for the error in the calculation, the energies of the two isomers are the same. Therefore the whole calculated value needs to be looked at when comparing the energies. It can be seen the cis isomer has a lower energy in comparison to the trans. Using the variation principle, the lowest energy isomer is the most favourable.

Interestingly, looking for a sterics point of view the cis isomer would be the least favourable and therefore higher energy. Therefore there must be further reasoning as to why in this case, the cis isomer is the most stable.

Using the data in the table above, the energy difference between the cis and trans isomers was calculated at 3kJ/mol. This is small difference.

In this case as the cis isomer is more stable, the Cl ligands are considered relatively small, as the steric interactions are not sufficient to make the trans isomer the most favourable. Therefore in order to change the geometry of the molecule from cis to trans, we must increase the steric bulk of the PR3 group. This would increase the energy of the cis isomer and therefore destabilise the structure. This would cause the trans isomer, with reduced steric interactions to have the more favourable (lower) energy.

Comparison between cis and trans IR spectra

Using the frequency analysis previously completed we can use the output files to analyse the specific vibrational modes of both isomers.

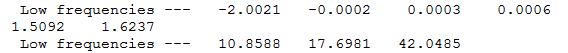

Firstly we will consider any vibrations which occur at a very low or negative frequency. The relevant section of the output log files for the cis and trans frequency analysis can be found below.

From the above two figures it can be seen that there are 3 low vibrational modes for each isomer. The tables below show the vibrational action for each mode. From this it can be speculated that at room temperature, there is resonance between the Cl atoms, i.e. Cl exchange.

We can now look at the CO vibrations noted in the IR spectra. These are tabulated below for the two complexes.

| Molecule | Cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 fully optimised structure | Trans-Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 | Literature [5] |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO vibrational frequency / cm-1 | 2023.6, 1958.6, 1949.1, 1945.5 | 2031.1, 1977.3, 1951.0, 1950.4 | 2018 |

| CO vibrational intensity | 595.7, 634.9, 1499.8, 762.03 | 3.8, 0.65, 1466.8, 1475.4 | - |

The data given in the table above is recorded respectively, i.e. CO vibrational frequency: 1,2,3,4 and CO vibrational intensity: 1,2,3,4.

From symmetry we would expect 4 different vibrational frequencies for the CO bonds in the cis complex and a single vibration for the CO bonds in the trans complex. The table above shows 4 vibrational frequencies are seen for the CO bonds in the cis isomer, which agrees with what we would expect from symmetry.

However for the trans isomer, more vibrations are seen than molecule symmetry dictates. This can be justified by looking at the bond angles in the trans complex (table...). From this we can see there is some molecular distortion from ideality as bond angles do not equal 90o and 180o as we would expect in a totally symmetric molecule. This deviation from symmetry means more vibrations are seen. Although, the vibrations at 2031.1 and 1977.3 cm-1 show intensities of 3.8 and 0.65 respectively, these are very low. This supports that it is the weak deviation from the molecules ideal centrosymmetric character which is causing these vibrations.

The presence of the frequencies at 1951.0 and 1950.4 cm-1 can also be explained. By looking at the modes of these vibrations (shown in figures .. and .. below) the same antisymmetric stretching action is seen between two CO groups in the same plane(with approximate 180o bond angle). Both these vibrations occur at very similar frequencies, this suggests it is the break in symmetry which causes the stretch to be separated into two non-degenerate vibrations.

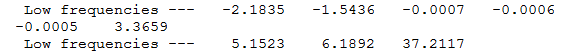

Mini Project - Conformations of Tetramethyldisilene

The differing conformations of disilene compounds are well documented. The first thermally stable disilene compounds were reported in 1981 by West[6]. Since this publication there has been research into the different conformations of disilenes compounds and these alkene analogues have been found to be conformational flexible. This high conformational flexibility is due to crystal packing forces.

There are 3 main conformations of disilene compounds which can be found in the figure below.

It is noted that the most observed conformations are trans-bent and planar. However some twisted conformations have been reported where the angle between the SiR2 planes is less than 90o[7]. Cis bent examples are also rare due to electron repulsion between singlet siliylenes on approach. In the cis bent case, steric repulsions between the R groups also cause strain and destabilise this conformation. The cis bent structure will not be investigated here due to it's low number of literature appearances.

In this project, the disilene compound, Me2Si=SiMe2 will be investigated. The conformations outlined about will be compared in terms of energy and and destabilisation supported via MO calculations.

General Gaussview errror An error was found during the calculations for this mini project. The error read as follows:

CConnectionGLOG::Parse_GLOG() Gaussian error detected

With this error the output log file would not open correctly. The only solution found to this problem (after many alterations to the input file) was to remove the OPT(MAXCYCLE=50) keywords from the input file. This allowed the output log file from the calculation to be read in Gaussview with no error warning. Therefore for all calculations in this mini project, the OPT(MAXCYCLE=50) was omitted from all input files.

Calculation methods and basis sets

Optimisation

For the structure optimisation, in all cases a rough optimisation was carried out followed by an accurate optimisation. To make the resulting energies comparable, the same method and basis sets were used on each conformation. For both rough and accurate a DFT-B3LYP method was used, due to it's reasonable accuracy and also good time frame for completion of the calculation. For the rough optimisation a low level 3-21G basis set was used, to get an approximation to a potential equilibrium structure. The accuracy of the basis set was increased for the more accurate optimisation by using a 6-311G(d,p) basis set. Pseudo potentials were not used in this analysis as the atoms were not considered 'heavy' enough to suit it's use. Not using the PP in the calculation unnecessarily, means the accuracy of the method was optimised. The accuracy of the accurate optimisations were also increased by using key words int=ultrafine scf=conver=9 in all cases.

Frequency Analysis

For all conformations and DFT-B3LYP method and 6-311G(d,p) basis set used so the calculation is the same accuracy as for the accurate optimisation.

MO analysis

Mo analysis, like frequency analysis was used with the same methods and basis sets as for the accurate optimisation in all cases. As seen below, MO analysis was not completed on transition state structures as these are no PES minima. Therefore only their relative energies can be compared.

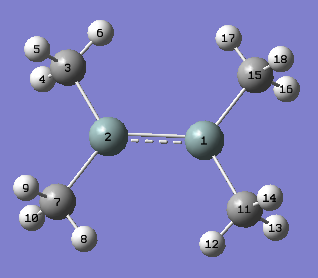

Trans-bent conformation

An initial trans bent structure was first optimised using a DFT-B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set. The output files can be found here: DOI:10042/to-5895 . The accuracy of optimisation was then increased by changing the basis set to 6-311G(d,p) (a DFT-B3LYP method was still employed). Key words were added to the input file to use ultrafine convergence (int=ultrafine scf=conver=9) which further increases the accuracy of the calculation The output files for this more accurate optimisation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5943

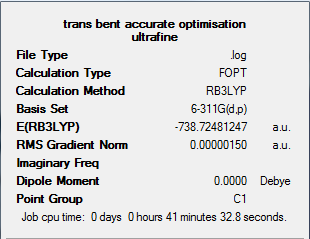

The results summary for this optimisation can be found below.

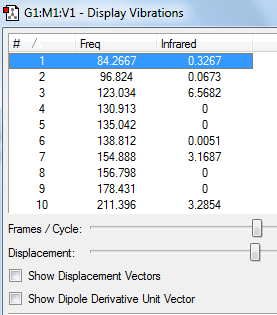

Frequency analysis was then completed to determine if the structure is an equilibrium structure. The output file for this calculation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5944 The output log file shows that the maximum displacement value did not converge during this calculation. This means there is some inaccuracy to the IR spectra and computated vibrations, however the accuracy could be improved further by using an MP2 method or higher level basis set. Another concern from this calculation was a low frequency of -7.81cm-1. Usually we would consider this value as truly negative (as it is <-5cm-1) however due to the non-full convergence, this is frequency can be considered as non negative. This is also supported by the vibrational spectra, discussed below.

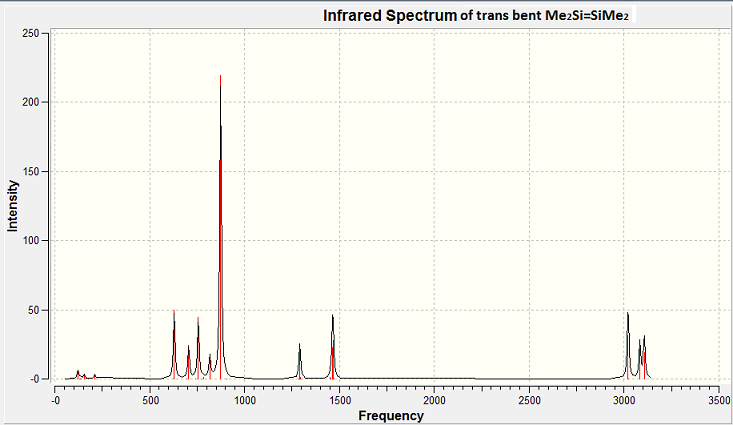

The formatted checkpoint file can be downloaded to produce the IR spectra and molecular vibrations. From the screen-shot below. We can see the -7.81cm-1 vibration is not noted in the IR spectra, therefore we can consider the accurately optimised structure, to be a ground state equilibrium structure.

Figure 18 above shows the IR spectra of the trans bent confirmation of the investigated disilene. Below are some assigned peaks. An Si=Si stretch was found from the output checkpoint file (visualised on GaussView) at 429cm-1. However an Si=Si stretch would not be shown in an IR spectrum as this stretch would not change the dipole moment of the molecule.

High intensity peaks were analysed for their vibrational modes. These can be found in the table below.

The above table shows the main contributions to the IR spectra for the trans bent structure are by C-H stretches and rotations. Three C-Si stretches are seen. And Si=Si stretch would not be expected to be seen in the spectra as previously discussed.

MO analysis was also completed for this structure. Results of which can be found below. The output files for this calculation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5984

| MO | View 1 | View 2 |

|---|---|---|

| LUMO+2 |  |

|

| LUMO+1 |  |

|

| LUMO |  |

|

| HOMO |  |

|

| HOMO-1 |  |

|

| HOMO-2 |  |

|

The above table shows the MOs calculated for the trans bent structure. However as this is the only ground state structure, in depth analysis without a comparison is difficult.

Geometry of the trans bent structure

The appropriate geometric parameters for the trans bent structure can be found in the table below.

| Parameter | Trans bent tetramethyldisilene calculated value | Literature [8] value calculated value of (E)-[(tBu2MeSi)2MeSi](tBu2MeSi)SiSiMe(SiMetBu2)(DFT-B3LYP, 6-311G(d,p)) |

|---|---|---|

| Si=Si Bond length / Å | 2.18 | 2.20 |

| Si-C bond length / Å | 1.90 | 1.91 |

| C-H bond length / Å | 1.09 | - |

| C-H bond length / Å | 1.09 | - |

Planar conformation

Problems

Some problems were noted whilst using Gaussview for the optimisation of the planar Me2Si=SiMe2. Firstly the structure was optimised roughly using a DFT-B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set. However this resulted in changed of symmetry and conversion of the planar structure to trans bent. Therefore steps were taken to constrain the geometry of the initial planar structure to D2h. This initially prevented conversion to the trans bent structure. However on accurate optimisation (DFT-B3LYP method and 6-311G(d,p) basis set) followed by frequency analysis this structure was confirmed as a transition state.

In order to achieve an equilibrium planar structure, the H atoms on the methyl groups were be rotated to relieve less steric strain. However because of this rotation, the previous D2h symmetry was disrupted and therefore the symmetry could not be constrained. This caused the structure to convert to trans bent on rough optimisation.

In order to solve this problem further action was taken, this is explained below.

Process

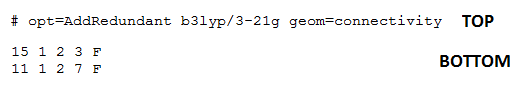

A two step optimisation process was first carried out on a planar structure of Me2Si=SiMe2. The initial rough optimisation calculation was completed using a DFT-B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set. As previously described the methyl H atoms were rotated to relieve steric strain in the initial structure prior to optimisation. The input file was then altered to freeze the dihedral angles in the molecule. The figure below shows the atomic labelling for the planar structure and the relevant section of the Gaussian Input File which shows the alterations made to freeze the appropriate dihedral angles.

The two diagrams (left and above) show that the Gaussian Input file for the rough optimisation of the planar structure include dihedral angle freezing, for the dihedral angles between C15-C3 and C11-C7. This dihedral angle freezing was carried out for all other calculations on non-trans bent conformations.

A rough optimisation was then calculated, the output files for which can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5946

A more accurate optimisation of the planar structure was then completed on this initially optimised structure. An DFT-B3LYP method was used with a 6-311G(d,p) basis set to increase accuracy, whilst maintaining dihedral angle freezing. Key words int=ultrafine scf=conver=9 were included to ensure an accurate optimisation. The output files for this analysis can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5950

The resulting optimised planar disilene structure can be found below.

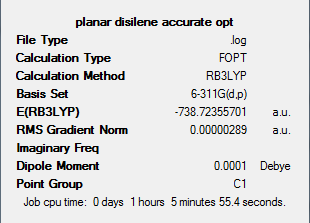

The convergence of the accurate and rough optimisations can be seen from the output file. The result summary for the accurate optimisation can be found below.

Frequency analysis was then completed on the above optimised structure. This will allow us to confirm if the structure is indeed an equilibrium structure. The frequency analysis was carried out using the same method and basis set as the accurate optimisation. The output file for this can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5951

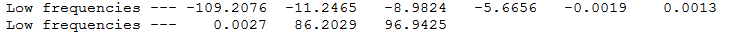

However from the output log file it can be seen that there are highly negative vibrations present. These are shown below.

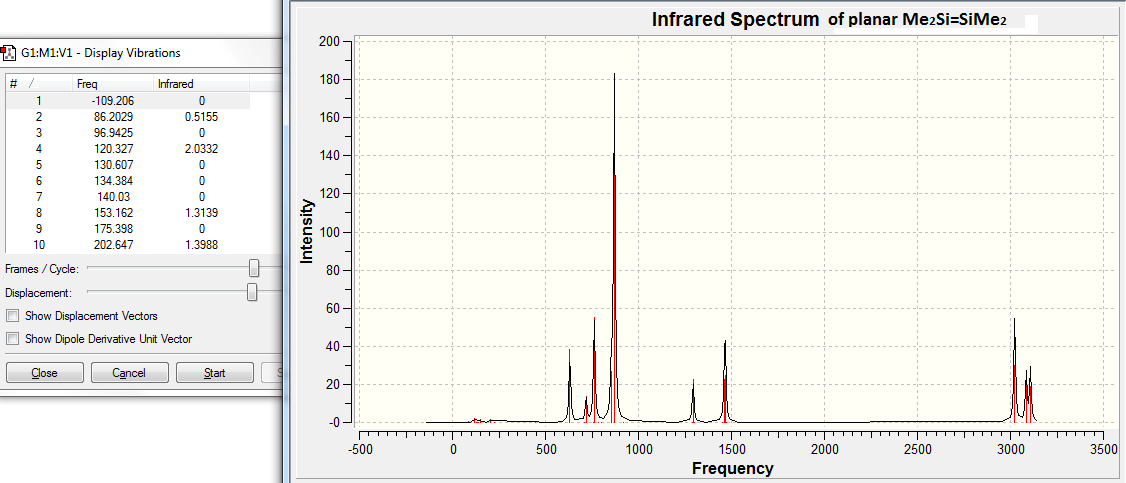

The appearance of the -109.21cm-1 frequency is confirmed in the IR spectra shown below.

The vibration at -109.21cm-1 can be investigated to find out the nature of the vibration. This is done in the table below.

Due to the nature of this negative vibration shown above, the optimised planar structure is determined as transition state.

Twisted - 54.4o twist angle

A twisted structure noted in literature[7]was found to have a twist angle (i.e. angle between two R group planes) of 54.4o, therefore this specific structure was investigated here.

Problems

Similar problems were found for the optimisation of the twisted structure as to the planar structure. Therefore the dihedral angles were also frozen in this case. The alterations made to the the input file for the rough optimisation were the same as for the planar structure.

Process

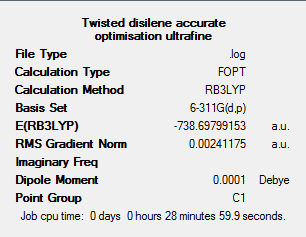

A rough optimisation (method:DFT-B3LYP, basis set:3-21G) was first completed on an intitial twisted Me2Si=SiMe2 structure with a twist angle of 54.4o. The output file for this optimisation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5954 . An accurate optimisation was then conducted using a DFT-B3LYP method and 6-311G(d,p) basis set, convergence was set to ultrafine as previous. The output file for this calculation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5955 From the output files it can be seen that both calculations fully converged. The resulting structure for the accurate optimised twisted (54.4o) disilene can be found below along with the results summary for the accurate optimisation.

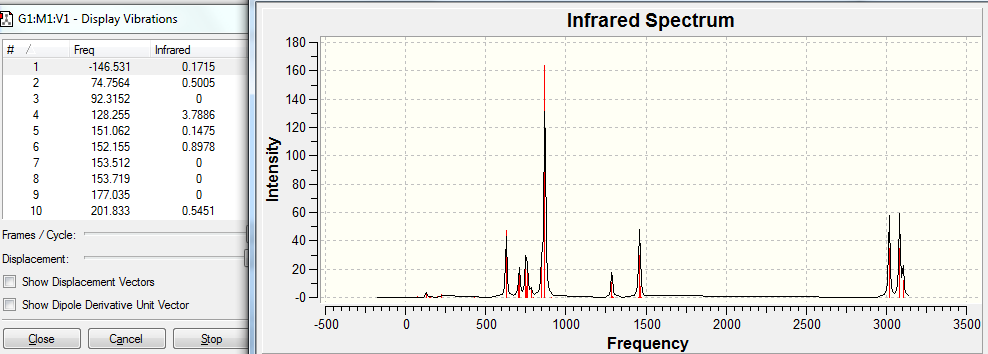

Frequency analysis was also completed, using the same DFT-B3LYP method and 6-311G(d,p) as used for the accurate optimisation. The output files for this can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5956 . On analysis of the output log file, negative frequencies were seen. The specific vibrational modes were then analysed from the output checkpoint file and the IR spectrum produced. These can be found below.

The above figure shows that there is a negative vibrational mode at -146.5cm-1. This vibrational mode can now be looked at in more detail. This is done in the table below.

Because of the nature of this negative vibrational mode, this twisted structure is determined as a transition state.

Twisted 90o structure

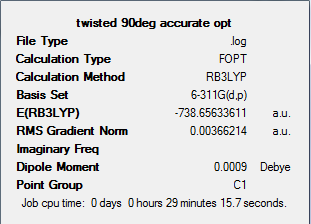

In order to relieve any possible steric strain in the previous twisted structure, the twist angle was increased. A rough optimisation was completed on this structure and the output files for this can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5960 . An accurate optimisation was then completed, the output file for which can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5961 . The results summary can be found below with the accurately optimised structure.

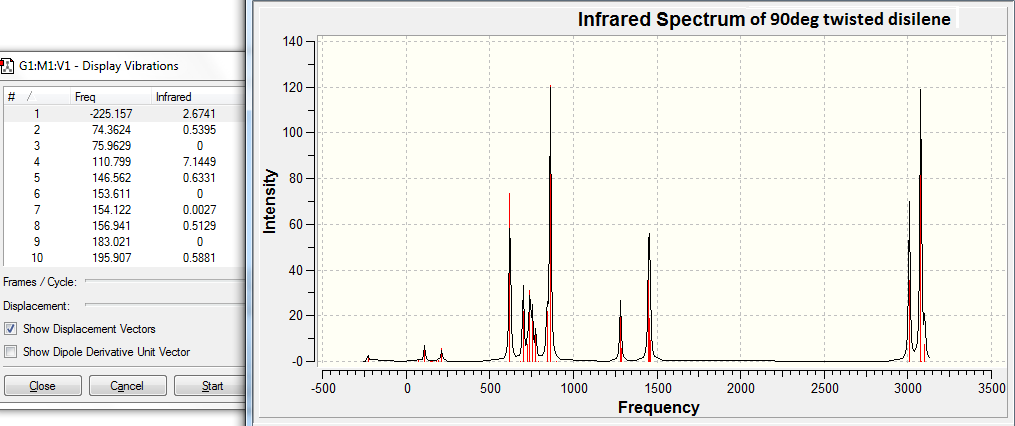

Frequency analysis was also completed on this twisted structure, to see if an equilibrium structure was achieved. The output files for this can be found at: DOI:10042/to-5962 . Once again on analysis of the output file we see a negative frequencies. The vibrational modes and IR spectrum can be analysed to see if any of these negative vibrations are present.

The above figure shows that the largely negative -225.2cm-1 vibration does occur in the IR spectrum. The table below analyses this vibration in more detail.

Conclusions from raw analysis

It can be seen above that only one true equilibrium structure has been found for Me2Si=SiMe2. This is the trans bent structure. Therefore only MO analysis and further IR analysis was conducted on this species. However the relative energies of the trans bent structure and the other transition states can be done.

Energy comparison

The table below shows the energies in Hartees and kJ/mol for each of the optimised species.

| Structure | Energy (accounting for error) / Hartrees | Energy (raw) / Hartrees | Energy (accounting for error) / kJ/mol | Energy (raw) / kJ/mol | Energy difference relative to trans bent / kJ/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans bent | -738.725 ± 0.0038 | -738.72481247 | -1.93952x106 ± 10 | -1.939522x106 | - |

| Planar TS | -738.724 ± 0.0038 | -738.72355701 | -1.93952x106 ± 10 | -1.939519x106 | 3 |

| Twisted (54.4o) TS | -738.698 ± 0.0038 | -738.69799153 | -1.93945x106 ± 10 | -1.939452x106 | 70 |

| Twisted (90o) TS | -738.656 ± 0.0038 | -738.65633611 | -1.93934x106 ± 10 | -1.939342x106 | 180 |

Using the data above approximations can be made about the relative stability of the planar and twisted equilibrium structures of disilenes. As the more stabilised the transition state for an equilibrium structure, the more likely it's formation.

The table above shows the different energies of the optimised species along with the energy difference between each transition state (TS) structure and the trans bent. It can be seen that there is a small energy difference (3kJ/mol) between the trans bent and planar TS. This suggests that a relatively small increase in size of the R groups (R=Methyl in this investigation) would favour the planar structure. However for the twisted structures to become favourable, there must be a very large increase in the R group size. This is supported by literature [9].

These deductions are supported by literature. Sekiguchi[7]reported a twisting angle of 54.4o for R2Si=SiR2 where R is SiMetBu2. Therefore in this case, the increase in steric bulk (in comparison to Me) was sufficient to stabilise the twisted (54.4o) structure.

However it is noted that twisted 90o disilenes have not been recorded experimentally. This suggests that the R group (with very large steric bulk) required to stabilise this structure is not adequate for reaction.

Final Conclusions

This project has shown that for the specific disilene and the structures investigated (Me2Si=SiMe,sub>2) the trans bent structure was the only ground state. However this investigation could be further improved. Using a more accurate MP2 method and more accurate basis set, such as cc-pVQZ. This would increase the accuracy of the optimisation calculations, and therefore the corresponding ground state to the transition state structure could be found.

However it can be said that steric contributions are large factors which determine the most stable conformation of a disilene structure. In this case the R group is reasonably small and so the trans bent is most favourable. This is supported by the trans bent MO analysis which shows many antibonding interactions.

References

- ↑ S. E. Jeffs, R. W. H. Small and I. J. Worrall, Structure of Tribromotris(pyridine)thallium(III), [TlBr3(C5H5N)3]DOI:10.1107/S0108270184009719

- ↑ E. R. Lory, R. F. Porter and S. H. Bauer, The structure of bis(trifluorophosphine)diborane(4), determined by electron diffractionDOI:10.1021/ic50099a043

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 F. A. Cotton, D. J. Darensbourg, S. Klein and B. W. S. Kolthammer, Steric contributions to the solid-state structures of bis(phosphine) derivatives of molybdenum carbonyl. X-ray structural studies of cis-Mo(CO)4[PPh3-nMen]2 (n = 0, 1, 2) DOI:10.1021/ic00131a055

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 G. Hogarth and T. Norman Crystal structures of trans-[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 and 1,4-bis(diphenylphosphino)-2,5-difluorobenzene DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X

- ↑ L. Hirsivaana, M. Haukka and J. Pursiainen, Intramolecular hydrogen bonding and cation p-interactions affecting cis–trans isomerization in tungsten hexacarbonyl derivatives of 2-pyridyldiphenylphosphane and triphenylphosphane DOI:10.1016/S1387-7003(00)00131-3

- ↑ R. West, M. J. Fink and J. Michl, Tetramesityldisilene, a Stable Compound Containing a Silicon-Silicon Double BondDOI:10.1126/science.214.4527.1343

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 A. Sekiguchi, S. Inoue, M. Ichinohe and Y. Arai, Isolable Anion Radical of Blue Disilene (tBu2MeSi)2SiSi(SiMetBu2)2 Formed upon One-Electron Reduction: Synthesis and CharacterizationDOI:10.1021/ja040079y

- ↑ Dr. M. Nag and Prof. P. P. Gaspar, Theoretical Calculations on the Tetramethyldisilene Rearrangement: A New Approach to an Old Mechanistic Problem DOI:10.1002/chem.200901024

- ↑ Faessler and Grutzmacher, Chem. Eur. J.', 2006, 6, 2317