Rep:Mod:em2815ts

Introduction

Potential Energy Surfaces

A potential energy surface (PES) describes the energy of a system in terms of certain parameters, for example nuclear position. For a linear molecule, the potential energy is dependent on 3N-6 degrees of freedom ie normal modes of vibration, where N = the number of atoms.[1] From the PES, a reaction coordinate can be derived; this is a progress variable which describes the reaction. It shows the progression of reactants to products and predicts the exact probability that a certain configuration will reach the product state.

The salient points on a PES are the stationary points, where the gradient, given by the first derivative, is 0. These points correspond to the reactants, products or transition states of the reaction. The curvature of these points, indicated by the second derivative, indicates the type of stationary point and allows the differentiation between the minima and the transition state.

It can be noted that the gradient and curvature of these points correspond to the force and force constant, respectively.

Reactants and Products

If the second derivative is > 0 with respect to all 3N-6 degrees of freedom, the stationary point is a minimum. This represents a minimum on the reaction coordinate. There are different types of minima, for example global and relative: the former is the lowest energy minimum which corresponds to the products and the latter can correspond to the reactants.

Transition State

If the second derivative is < 0 along the reaction coordinate but > 0 for all other degrees of freedom (in other words, a maximum along the reaction coordinate but a minimum in all other directions), the stationary point corresponds to a transition state. This gives rise to a single negative Hessian eigenvalue and represents a maximum energy point along the reaction coordinate (it is the maximum on the minimum energy path which connects the reactant and product minima).

Nf710 (talk) 10:29, 16 April 2018 (BST) The eigenvetors are linear combinations of the degrees of freedom. hence Why they look like vibrations when you move along them.

Computational Methods

During this investigation, GaussView was used to locate the transition states of the relevant reactions. Two main computational methods were used, PM6 and B3LYP. PM6 is a fitted semi-empirical method which uses experimental data, ie previously calculated integrals, to solve the Hamiltonian matrix. This method is advantageous since it does not need to calculate all of the integrals in each optimisation; this makes it less expensive and also much faster. The PM6 method is, however, less accurate because it uses many approximations.[2] [3]

B3LYP is a method which uses Density Functional Theory (which uses the electron density) to calculate the terms of the Hamiltonian and the Hartree Fock calculation (which uses electronic position) to find the exchange correlation terms.[2] This method is extremely accurate but it is slower than the PM6 method since it does not use precalculated values. In this investigation, the B3LYP method uses the 6-31G(d) basis set, which is a set of functions which represent atomic orbitals which can be linearly combined to form molecular orbitals.[4] The 6-31G(d) set is high enough such that enough atomic orbitals are used to give an accurate view of the molecular orbitals without costing the computational effort too much. Higher basis sets result in higher computational effort which is expensive and time-consuming; the 6-31G(d) basis set offers a good compromise between accuracy and computational effort.

Nf710 (talk) 10:32, 16 April 2018 (BST) You have clearly read beyond the script here and have understood the methods well. You could however have added some equations to compliment your discussion.

Locating the Transition State

The following methods were used to locate the transition states.

Method 1

Method 1 involves the use of the previously PM6 optimised reactants to estimate the transition state structure by altering the distances between the reacting terminii. The estimated structure is then optimised to a transition state at the PM6 or/and B3LYP/6-31G(d) level(s). This method is good because it is the fastest, but it is very unreliable and requires knowledge of the transition state (it will only work if the initial guess of the transition state structure is extremely close to the actual structure).

Method 2

Method 2 is similar to method 1 in that it involves the use of previously optimised reactants. The optimised reactants are placed close together and the distances between the reacting atoms are set. These pairs of reacting atoms are then 'frozen' and the frozen structure is optimised to a minimum. The resulting molecule is then optimised to a transition state at the PM6 level and can be further optimised at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. This method is much more reliable than method 1.

Method 3

Method 3 is slightly different to methods 1 and 2 in that it begins with the product. The product is constructed and optimised to a minimum at the PM6 level. The new bonds which have formed during the reaction are then broken and the distances between the reacting atoms are set. These bonds are then frozen and the structure is optimised to a minimum at the PM6 level. The resulting molecule from this calculation is then optimised to a transition state at the PM6 level and can be optimised further at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. Method 3 is the most reliable method since it does not require knowledge of the transition state and it is very easy and more likely to succeed. The only downsides of this method are that it requires more steps and that it may not work with all reactions.

Checks

The success of each optimisation was determined by analysing the vibrations/frequency calculations. All molecules which were successfully optimised to a minimum yielded all positive frequencies whereas molecules which were successfully optimised to a transition state resulted in the first normal mode having a negative frequency, indicative of an imaginary number. The transition state has a negative force constant, therefore when substituted into the equation for the simple harmonic oscillator, the output frequency is an imaginary number.

Part 1: Reaction of 1,3-butadiene with Ethene

(Fv611 (talk) Great work across the whole exercise. Well done!)

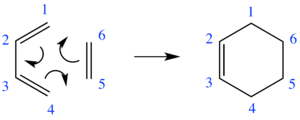

Scheme 1 shows the Diels Alder reaction of ethene and 1,3-butadiene.

The reactants were optimised at the PM6 level and the transition state was located using method 3, also at the PM6 level. The success of this reaction was confirmed by the presence of an imaginary frequency at 948.48i cm-1. The MOs generated computationally have been correlated with the MOs in Fig 1a (see Table 1).

Molecular Orbitals

The molecular orbital diagram for this reaction can be seen in Fig 1a and the molecular orbitals found computationally can be seen below.

| Ethene | 1,3-butadiene | Transition State | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

LUMO (corresponds to MO 3) |

LUMO (corresponds to MO 2) |

LUMO +1 (corresponds to MO 8) | ||||||

LUMO (corresponds to MO 7) | ||||||||

HOMO (corresponds to MO 4) |

HOMO (corresponds to MO 1) |

HOMO (corresponds to MO 6) | ||||||

HOMO-1 (corresponds to MO 5) |

The MO diagram shows that the LUMO of 1,3-butadiene combines with the HOMO of ethene in-phase and out-of-phase to generate the HOMO and LUMO of the transition state, respectively. The HOMO of 1,3-butadiene also combines with the LUMO of ethene in-phase (a stabilising interaction) to generate HOMO-1 and out of phase (a destabilising interaction) to generate LUMO+1.

Evidently, orbitals of the same symmetry combine to form a molecular orbital with a retention of symmetry. Hence, two symmetric orbitals overlap to form an orbital which is symmetric and two antisymmetric orbitals overlap to form an antisymmetric orbital. If the orbitals have the same symmetry, they will overlap spatially and so the overlap integral will be non-zero (thus, the overlap integral is non-zero for symmetric-symmetric and antisymmetric-antisymmetric interactions and 0 for antisymmetric-symmetric interactions). This shows that for a reaction to be allowed, there is a requirement for the symmetry to be the same.[5]

In normal electron demand Diels Alder reactions, the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile are closer in energy than the LUMO of the diene and the HOMO of the dienophile.[6] After obtaining the energies of the molecular orbitals by looking at the MO analysis, it was found that this statement is true for this case, hence the reaction between 1,3-butadiene and ethene involves normal electron demand.

Carbon-Carbon Bond Lengths

| Bond | Bond Length in Reactants (Å) | Bond Length in Transition State (Å) | Bond Length in Product (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | 1.3334 | 1.3798 | 1.5008 |

| 2-3 | 1.4708 | 1.4111 | 1.3370 |

| 3-4 | 1.3334 | 1.3798 | 1.5009 |

| 4-5 | N/A | 2.1147 | 1.5371 |

| 5-6 | 1.3273 | 1.3818 | 1.5346 |

| 6-1 | N/A | 2.1148 | 1.5371 |

The carbon-carbon bond lengths in ethene, 1,3-butadiene, the transition state and the cyclohexene product are shown in Table 2. It can be seen that bonds 1-2 and 3-4 get longer as the reaction proceeds from the reactants to the products; this makes sense since the hybridisation of the carbon atoms is changing from sp2 to sp3 as the double bonds change to single bonds. As expected, bond 2-3 gets shorter as the cyclohexene double bond forms (the carbon atoms go from sp3 to sp2). Bonds 4-5 and 6-1 become shorter from the transition state to the product as the reacting terminii approach each other as the bonds form. It can be noted that the distances between the two pairs of reacting atoms in the transition state (4-5 and 6-1) are shorter than 2x the Van der Waals radius of the C atom (1.70 Å), thus confirming the interaction between the reacting terminii and the partial formation of these bonds in the transition state.

The bond lengths obtained computationally are mostly consistent with the typical sp2 and sp3 C-C bond lengths of 1.34 and 1.54 Å, respectively.[7] One deviation, however, is bond 2-3 in the reactant butadiene. This length is slightly shorter than the typical sp3 C-C bond length due to the delocalised pi system. Another notable deviation involves bonds 1-2 and 3-4 in the product, which are shorter than the expected sp3 length due to the fact that one carbon atom of each of these bonds is sp2 hybridised.

Vibration Analysis

Fig 1b: the vibration at the transition state of the reaction between 1,3-butadiene and ethene

The vibration which corresponds to the reaction path at the transition state (see Fig 1b) is the vibration with the negative (imaginary) frequency. The animation shows that the reacting terminii of both reactants move towards each other simultaneously as the two new bonds form synchronously (ie, at the same time). This is also confirmed by the IRC, since both bonds form in Step 10 .

Log Files

LOG file of 1,3-butadiene minimum PM6

LOG file of ethene minimum PM6

LOG file of transition state PM6

LOG file of product minimum PM6

Part 2: Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole

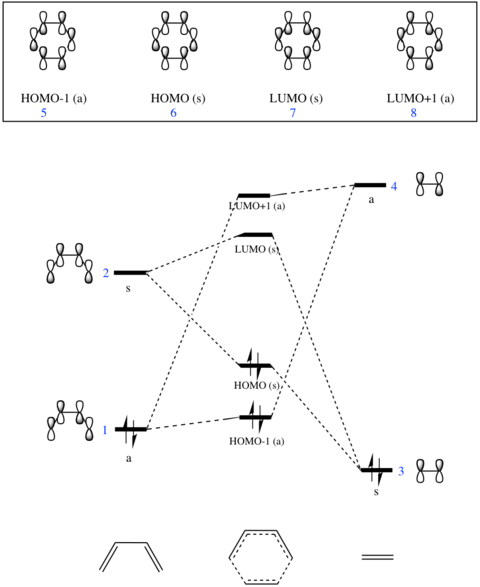

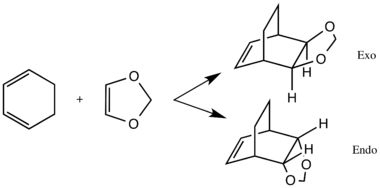

Scheme 2 shows the Diels Alder reaction of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole. This reaction can go via two pathways: exo or endo.

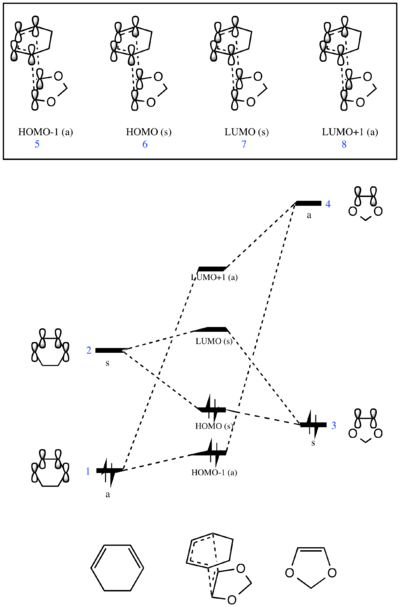

The reactants and products were optimised at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level and the transition state was located using method 3, also at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. The success of the endo and exo reactions were confirmed by the presence of the imaginary frequencies at 520.90i and 528.79i cm-1, respectively. The MOs generated computationally have been correlated with the MOs in Fig 2 (see Table 3).

Molecular Orbitals

The molecular orbital diagram for the exo reaction can be seen in Fig 2 and the molecular orbitals found computationally can be seen below.

| Cyclohexadiene | 1,3-dioxole | Endo Transition State | Exo Transition State | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

LUMO (corresponds to MO 2) |

LUMO (corresponds to MO 4) |

LUMO +1 (analogous to MO 8) |

LUMO +1 (corresponds to MO 8) | ||||||||

LUMO (analogous to MO 7) |

LUMO (corresponds to MO 7) | ||||||||||

HOMO (corresponds to MO 1) |

HOMO (corresponds to MO 3) |

HOMO (analogous to MO 6) |

HOMO (corresponds to MO 6) | ||||||||

HOMO-1 (analogous to MO 5) |

HOMO-1 (corresponds to MO 5) |

The MO diagram shows that the LUMO of cyclohexadiene combines with the HOMO of 1,3-dioxole in-phase and out-of-phase to generate the HOMO and LUMO of the transition state, respectively. The HOMO of cyclohexadiene also combines with the LUMO of 1,3-dioxole in-phase (a stabilising interaction) to generate HOMO-1 and out of phase (a destabilising interaction) to generate LUMO+1.

This MO diagram can be compared to that of the Diels Alder reaction in Part 1. The presence of the electron-donating oxygen atoms in 1,3-dioxole destabilises the HOMO and LUMO of the alkene therefore they are higher in energy compared to the simple ethene molecule. This means that the HOMO of the electron deficient 1,3-dioxole is closer in energy to the LUMO of the electron rich cyclohexadiene, hence these are the orbitals that overlap and interact. Since the HOMO of the alkene (dienophile) and the LUMO of the diene are closer in energy than the LUMO of the alkene and the HOMO of the diene, the reaction goes via inverse electron demand.[5][6]

It is worth noting that the endo pathway would produce transition state molecular orbitals which are lower energy than those depicted for the exo pathway.

(Fv611 (talk) You can't compare MO energies on different potential energy surfaces, so your last point should have been discussed in terms of relative energy gaps instead.)

Nf710 (talk) 10:46, 16 April 2018 (BST) You could have compared this by doing a single point energy on the reactants

Thermochemistry

| Endo | Exo | |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | +157.53 | +165.41 |

| Reaction Energy (kJ/mol) | -70.89 | -65.64 |

The 'Thermochemistry Data' from the optimisations were used to calculate the activation and reaction energies of the exo and endo pathways, see Table 4. Since the endo pathway has a smaller activation energy, it is kinetically favoured and leads to the kinetic/endo product, which is faster formed. This is the case because there is less steric clash in the endo transition state. Another possible reason is a stabilising secondary orbital overlap between the pi system of the diene and the pi orbitals of both oxygen atoms in 1,3-dioxole which decreases the energy of the transition state, lowering the activation energy.

The reaction energy for the endo pathway is also more negative than that for the exo pathway, suggesting that the endo product is the more thermodynamically stable (lower energy) product. This is the case because of the same reasons discussed earlier: the secondary orbital interaction is also present in the endo product and there is less steric clash. Hence, the endo product is kinetically and thermodynamically favoured.

The exo pathway has a larger activation energy and a smaller reaction energy than the endo pathway. This shows that the exo product is less thermodynamically stable (higher energy) than the endo product. The aforementioned secondary orbital interaction is not possible in the exo product since the 1,3-dioxole molecule is in the wrong orientation for the pi systems of the oxygen atoms and the diene to overlap. The exo product therefore does not benefit from the additional stabilisation, and this coupled with the fact that there is more steric clash means that the exo product is higher in energy.

Nf710 (talk) 10:50, 16 April 2018 (BST) This is a good section. Your energies are correct and you have come to the corretc conclusions. you could have backed up your discussion with some diagrams. Nf710 (talk) 14:11, 19 April 2018 (BST) Further to your email. You lost marks because you have bothered to draw any figures to explain what you are talking about. such as for the sterics and the SOO. This would have also complimented your discussion on the thermodynamics and kinetics. Secondly your discussion on the electron demand, its just your opinion and is completely qualitative. You can actually run a calculation to investigate the electron demand which you haven't done., to get a quantitative analysis. Your other 2 questions and intro were really good and you still get a very high mark. compared to the other labs you would have done.

Log Files

LOG file of dioxole minimum B3LYP

LOG file of cyclohexadiene minimum B3LYP

LOG file of endo transition state B3LYP

LOG file of exo transition state B3LYP

LOG file of endo product minimum B3LYP

LOG file of exo product minimum B3LYP

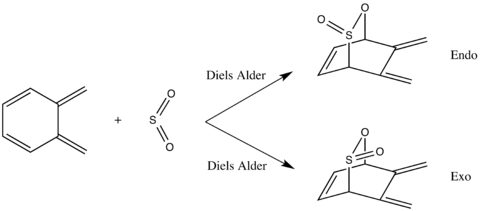

Part 3: Reaction of o-Xylylene and SO2

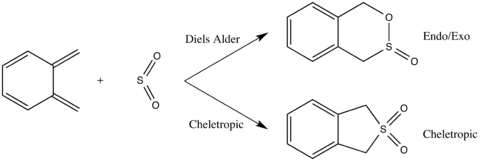

Scheme 3 shows the Diels Alder and Cheletropic reactions of o-xylylene and SO2.

The reactants and products were optimised at the PM6 level and the transition state was located using method 3, also at the PM6 level. The success of the endo, exo and cheletropic reactions were confirmed by the presence of the imaginary frequencies at 333.79i, 351.67i and 486.55i cm-1, respectively.

IRC Calculations

The Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate calculations for the endo, exo and cheletropic reactions can be seen in Figs 3a, 3b and 3c. Evidently, for the Diels Alder reactions, the reacting terminii of both reactants move towards each other at different rates. The C-O and C-S bonds are formed at different rates due to asymmetry, hence the bond formation is asynchronous. For the endo pathway, the C-S bond forms in step 56 whereas the C-O bond forms in step 52 and for the exo pathway, the C-S and C-O bonds form in steps 64 and 60, respectively. This however is not the case for the cheletropic reaction. Since this reaction is symmetric, the reacting terminii move towards each other at the same rate and the C-S bonds are formed synchronously (both C-S bonds form in step 78 of the IRC).

(Don't use the word "rate" here, as their formation is staggered in time. It's very difficult to say when exactly a "bond" is formed. The bonds that GaussView uses are aesthetic (except in molecular mechanical calculations) and are decided when atoms cross a cutoff distance Tam10 (talk) 11:48, 4 April 2018 (BST))

o-Xylylene Stability

The IRCs for the reactions show that the two double bonds in the 6 membered ring of xylylene break and a delocalised ring structure forms. This shows that xylylene is extremely reactive since there is a very large driving force for aromatisation.

Thermochemistry

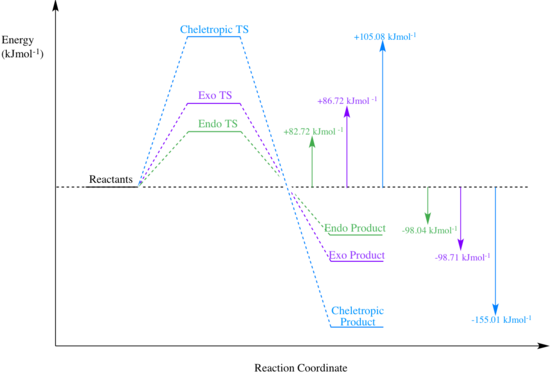

| Endo | Exo | Cheletropic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | +82.72 | +86.72 | +105.08 |

| Reaction Energy (kJ/mol) | -98.04 | -98.71 | -155.01 |

The 'Thermochemistry Data' were used to calculate the activation and reaction energies of each of the three pathways, see Table 5. The endo pathway has the smallest activation energy, therefore it is kinetically favoured (thus the endo product is the kinetic product). The endo transition state could be lower in energy because there is reduced steric clash. It may also be stabilised by a secondary orbital overlap between the pi systems of the xylylene and the oxygen atoms from SO2. Since these factors stabilise the transition state, they result in a lower activation barrier.

The exo transition state has more steric clash and does not benefit from the secondary orbital overlap therefore it is higher in energy. Furthermore, the cheletropic transition state consists of a highly strained 5 membered ring. This is much higher in energy than the 6 membered ring in the exo and endo transition states (6 membered rings are essentially strain-free), therefore the cheletropic transition state is much less stable, resulting in the largest activation barrier.

The cheletropic reaction has the most negative reaction energy, indicating that the cheletropic product is the most energetically stable and therefore the thermodynamic product. This is the case because the S=O bonds are extremely strong and high energy therefore they stabilise the product.

The values for activation energy and reaction energy were used to generate the reaction profile shown in Fig 4.

Alternative Diels-Alder Pathway

So far, the reaction at the terminal diene has been discussed. There is also an alternative reaction pathway involving the second cis-butadiene fragment which is in the 6 membered ring of o-xylylene. See Scheme 4.

The IRC calculations and thermodynamic data for the exo and endo pathways involving this cis-butadiene fragment can be seen below in Figs 5a & 5b and Table 6. The activation energies for both pathways are extremely high, indicating that reactions at this site are very kinetically unfavourable. The reaction energies are also positive, indicating that both the exo and endo products are relatively high in energy compared to the products of terminal diene pathway discussed earlier. Since both products are less stable, there is a lower driving force for the xylylene compound to react at this site. The positive reaction energy also indicates that the reactions are endothermic and hence thermodynamically unfavourable.

| Endo | Exo | |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | +112.94 | +120.78 |

| Reaction Energy (kJ/mol) | +17.22 | +21.67 |

The kinetic and thermodynamic unfavourability of these pathways can be explained by the fact that these reactions do not achieve aromatisation of the xylylene ring in the product. The conjugation is also lost in this pathway, therefore the reactants are much less stable and are disfavoured. Aromatisation and conjugation can however be achieved and maintained in the reaction occurring at the terminal diene, therefore this is the kinetically and thermodynamically favourable site of the reaction.

Log Files

LOG file of SO2 Reactant Minimum PM6

LOG file of o-Xylylene Reactant Minimum PM6

LOG file of endo transition state PM6

LOG file of endo product minimum PM6

LOG file of exo transition state PM6

LOG file of exo product minimum PM6

LOG file of cheletropic transition state PM6

LOG file of cheletropic product minimum PM6

LOG file of cheletropic pathway IRC

Alternative Pathway

LOG file of endo transition state (reacting in the xylylene ring) PM6

LOG file of endo product minimum(reacting in the xylylene ring) PM6

LOG file of exo transition state (reacting in the xylylene ring) PM6

LOG file of exo product minimum (reacting in the xylylene ring) PM6

LOG file of endo pathway (reacting in the xylylene ring) IRC

LOG file of exo pathway (reacting in the xylylene ring) IRC

Conclusion

This investigation used the PM6 and B3LYP/6-31G(d) computational methods to locate the transition states of various cycloaddition reactions. Method 3 proved to be the most efficient and reliable method which lead to successful calculations. It was found that the type of reactants affected the type of reaction occurring; from part 1 to part 2, the addition of the heteroatoms in the alkene resulted in an inverse electron demand reaction, affecting the ordering of the orbitals involved in the reaction.

For part 2, the competition of different reacting pathways was investigated. The exo and endo pathways of the Diels Alder reaction of cyclohexadiene with 1,3-dioxole were observed and it was found that the endo pathway has a lower activation barrier than the exo pathway therefore the endo product is kinetically favoured. This product was also found to be more stable than the exo product, hence it is thermodynamically favoured too. It has been suggested that the kinetic and thermodynamic favouring of the endo product is due to the reduced steric clash and the secondary orbital overlap between the pi orbitals of the oxygen atoms and the pi system of the diene, which is only possible in the endo configuration.

In part 3, the competition of three different reacting pathways was investigated. SO2 can react with o-xylylene in a Diels Alder fashion, with one S atom and one O atom as part of a 6 membered ring, or in a cheletropic fashion, with just the S atom as part of a 5 membered ring. It was found that the endo product is kinetically favoured for this reaction since it has the smallest activation energy, however the thermodynamically favoured product is the cheletropic molecule. Although the cheletropic transiton state is disfavoured in terms of kinetics (due to the strained 5 membered ring), it is the most thermodynamically stable due to its strong and unreactive S=O bonds.

References

<references> [1]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 P. Atkin, J. Paula, Physical chemistry, 8th edn, 2006.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 X. Qu, D. Latino and J. Aires-De-sousa, J. Cheminform., 2013, 5, 1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 E. Lewars, Computational Chemistry: Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Molecular and Quantum Mechanics, 1st edn, 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 F. Jensen, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci., 2013, 3, 273–295.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 R. Hoffmann and R. B. Woodward, Acc. Chem. Res., 1968, 1, 17–22.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 D. Boger, Progress in Heterocyclic Chemistry, 1st edn, 1989.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 H. J. Bernstein, Trans. Faraday Soc., 1961, 57, 1649–1656.