Rep:Mod:elablablagdb

Name: Genco Devrim Barikan; CID: 00610085; Computational Lab, Module 1

Introduction

The applicability of the computational method in physical/chemical systems has been put to test numerous times ever since the discovery of the molecular mechanics theory by Allinger and the MM2 Force Field. The Force Field Method, differing from physics, makes use of the additive nature of potential energy terms in a system, which combines the output values of different potential energy functions, each related to a physical parameter. Each of these functions are empirical phenomena, and are calculated using advanced quantum mechanical methods. However, in simplest terms, the different parameters can be summed up as;

- Bond Length Potential Energy Contribution, given by Hooke’s Law

- Bond Angle Energy Contribution; similar to polar coordinates

- Torsion Angle Potential Energy Contribution, given by the dihedral angle, similar to Karplus Equation

- Electrostatic Potential Energy Contribution, given by Coulomb’s Law

- Van der Waals Potential Energy Contribution, given by Lennard-Jones Potential

The MM2 Force Field method relies on empirical data, and hence it will require most of the bonds to be defined prior to calculation. This can be viewed as a weakness, as other methods such as MOPAC have been developed that put focus on electronic interactions and only needs this to operate. The experiment focuses on both these methods separately and together, and investigates their weaknesses and strengths in the context of the study at hand.[1] [2] [3]

Molecular Mechanics

Regioselectivity in Diels-Alder Reactions: Cyclopentadiene Dimers

Diels-Alder: Outline

First documented in 1928, the Diels-Alder reaction is still considered to be one of the most efficient ways in the synthesis of unsaturated ring structures. The rapid formation of carbon-carbon bonds in a cycloaddition requires essentially no energy, and due to concerted nature of the reaction the process is highly stereoselective in that it is ortho/para directing. The stereoselectivity is further discussed in this section, and the simple definitions of the two different pathways are defined.

The reaction can either progress via a thermodynamic or a kinetic pathway. The endo and exo approaches and their products are given on the right. The endo approach intuitively forms the least stable species as the proximity of R1 and R2 would raise the energy associated with the overall steric hindrance of the molecule. This is absent in the exo-approach, hence the two pathways are assigned to the endo and exo approaches as the kinetic and thermodynamic respectively. Hence, energetically the formation of the exo product is expected at high temperatures. However, the kinetic product could dominate at low temperatures given the greater number of orbitals that could interact with the HOMO of the nucleophile. The localised orbital interaction of the exo approach is given on the right, and it can be seen that this approach lacks any sort of secondary stabilisation from the whole of the LUMO. Hence, the kinetic pathway may be observed given low temperatures. This preference is studied in the dimerization of cyclopentadiene. [4] [5]

Cyclopentadiene

The high stereospecificity of the Diels-Alder can be further observed in the dimerization reaction of two cyclopentadiene molecules. Despite being aromatic (2π e-, =4n+2), it shows unusual reactivity compared to other neutral aromatics such as benzene etc. due to its molecular orbitals. The classical/mechanical focus of Alligner’s MM2 calculations appear to be sufficient for giving a reasonable explanation the reaction, however the orbital theory behind the dimerization should also be noted for definitive results.

Cyclopentadiene has 5 molecular orbitals, ψ1(lowest-bonding), ψ2- ψ3 (doubly degenerate HOMO), and ψ4 - ψ5(doubly degenerate LUMO). The relatively energetic HOMO results in the molecule appearing as a reactive nucleophile, and along with its low-lying LUMO, two molecules can exhibit a diene-dienophile relationship, assumed ideal for a Diels-Alder type π4s + π2s cycloaddition reaction. The HOMO can be seen as the electron-rich diene, and the single-symmetrical unit of the low-lying LUMO as the electron-deficient dienophile. The reaction progresses stereoselectively under either Huckel’s (thermal, Δ) or Mobius’ (photo, hv) rules, dominated by orbital configurations.

Dimerization:Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Control

The MM2 calculations were carried out on the different products of the Diels-Alder reaction, namely the different cyclopentadiene dimers which were drawn in ChemBio3D software. The results are given below in Table 1.1, along with the MM2 calculations done on the hydrogenated products of the different dimers. The hydrogenation reaction is discussed later along in this section.

| Compound (energy in kcal/mol) | Dimerisation Product | Hydrogenation Product | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (exo) | 2 (endo) | 3 | 4 | |

| Energy in (kcal/mol) | ||||

| Stretch | 1.2856 | 1.2507 | 1.2785 | 1.0962 |

| Bend | 20.5791 | 20.8474 | 19.858 | 14.5238 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.838 | -0.8356 | -0.8347 | -0.5492 |

| Torsion | 7.6571 | 9.5109 | 10.8107 | 12.4981 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.4171 | -1.543 | -1.2216 | -1.0697 |

| 1,4 VDW | 4.2322 | 4.3195 | 5.632 | 4.5124 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.3776 | 0.4476 | 0.1621 | 0.1406 |

| Total MM2 Energy | 31.8766 | 33.9975 | 35.685 | 31.1521 |

| MM2 Energy Difference | +2.1209 | +3.8121 | ||

It is seen that Dimer 1, the exo product has an energy value lower than Dimer 2 by ≈ 2 kcal/mol. Most of this difference comes from the torsional strain parameter, which is intuitive, as the exo-approach gives the product with the less steric hindrance since there is no steric clash around the hydrocarbon bridge of the nucleophile. This is seen on the molecules shown in Table 1.1. Hence, Dimer 1 is the thermodynamic product. However, it is given that the cycloaddition results in the formation of the endo dimer, Dimer 2. Dimer 2 being the more energetic dimer, this indicates that the reaction is dictated by kinetics at room temperature, due to the optimal orbital interactions of the endo-approach between the HOMO and LUMO in the transition state.

The conclusion is that at room temperature, the cycloaddition will form the endo-product due to a more stabilised transition state, however, as the temperature is increased, the kinetic product is expected to go over the high-energy transition barrier to form the exo(thermodynamic)-product.

Hydrogenation

Table 1.2 shows Product 3 to be more energetic than Product 4 by ≈ 4 kcal/mol, which is a significant difference. In the mechanism (given below), this overall energy difference dictates, although the different parameters must be accounted for in order to get a clear explanation. Due to a relatively large difference, all parameters are expected to have different values by some degree, however the dominating ones can be isolated as bend and torsion.

From Dimer 2, the hydrogenation of both alkene bonds result in less bending energy, however the magnitude is what makes the difference. Product 3, which is obtained from the hydrogenation of the alkene bond farthest to the hydrocarbon bridge, shows little alleviation from a high bending energy. However, it is obvious that the alkene close to the hydrocarbon bridge is paramount for the reaction, as it is most likely to be the reason for the stability of Product 4. In Product 3, the bridgehead carbons that are already in a distorted sp3 geometry due to the strain from the bridge are being further distorted by the short neighbouring alkene bond. This extra strain is absent in Product 4, if not less due to a longer alkane bond. The relative bond lengths and angles can be seen in Table 1.1.

| Measurement | Product 3 | Product 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Display | Value | Display | |

| C-C-C (angle) | 98 |  |

101 |  |

| Bond length | (C=C)1.3 | (C-C)1.5 | ||

The results confirm the prediction, since an angle of 101 θ is closer to the optimum geometry than 98 θ, which is 109.5 θ for a tetrahedral sp3.

A quick note on torsional strain is the possible staggered/eclipsed conformation of any neighbouring hydrogens to the incipient alkane hydrogens. This is nearly non-existing in Product 3, due to the presence of only 1 hydrogen atom. However, Product 4 has 2 neighbouring hydrogen atoms neighbouring the newly-formed alkane, and since these are all conformationally-locked due to ring structure, the torsional strain is slightly higher for Product 4 than 3.

Therefore, the dimerization goes through a kinetic pathway, whereas hydrogenation goes through a thermodynamic one and the formation of Product 4 is expected to happen before Product 3 before both alkenes are hydrogenated.

Synthesis of Taxol: Intermediate Reactivity & Atropisomerism

Atropisomerism: Introduction

Strain over a C-C bond rotation is a common concept seen in the simplest of molecules. However, in structures already suffering from a residual strain often due to the presence of a ring species, such rotations may be unfavoured due to an unusually high torsional energy barrier, which theoretically makes the two (three, four etc.) species formed from C-C bond rotation conformers. Such conformers are called atropisomers, isomers arising from unfavoured C-C bond rotations. In the total synthesis of the anti-cancer drug Taxol, an intermediate is encountered that leads to the two atropisomers shown in the figure below.[6] [7] [8] The high energy barrier and the stability of these conformers may be dependent on numerous factors, and these factors are studied.

Results and Discussion

Results shown in table 2.1 gives the stable isomer as Intermediate 10, which could have been predicted prior to any calculation by looking at the position of the carbonyl and judging its proximity to the hydrocarbon bridge. At this point, the stabilizing contribution of the alkene (discussed later on) to the overall molecule can be overlooked as this will be present in both isomers. The stability of the isomer is dictated by steric hindrance arising from the clashing of the Van der Waahl’s radii of the bridgehead and the oxygen atoms. Initially, Intermediate 9 was thought to be somewhat favourable due to possible stabilization from H-bonding interactions arising from the proximity of the bridgehead hydrogens to the oxygen, however, even if such interactions do indeed exist, they are evidently overridden by the aforementioned steric clashing. These observations can be confirmed by looking at the energy values of the specific parameters. Intermediate 9 has a lower Non-1,4 VDW energy compared to 10 by ≈0.1 kcal/mol, however Intermediate 10 has a lower torsion value by ~ 2 kcal/mol. H-bonding may be somewhat present in the Non-1,4 VDW parameter, which would stabilise Intermediate 9 and give a lower Non-1,4 VDW value, but it is evident that steric interactions indeed dictate the stability of the intermediate structures, as 10 being the most stable one due to the anti-periplanar relationship of the carbonyl oxygen and the bridgehead.

Moreover, the conformation of the cyclohexyl group in the said intermediate structure was studied, given the possibility of different chair conformers. This can be viewed in Table 2.1, where the ring has been flipped to give the substituents at different positions, which in turn puts the ring in a more unfavourable position relative to the hydrocarbon bridge. This is proven by a high total MM2 energy value of 53 kcal/mol, with the major contributions isolated as Bend and Non-1,4 VDW energy parameters. The strain caused by the new conformation of the cyclohexyl ring gives a reasonable explanation for both these parameters.

| Energy (in kcal/mol) | Intermediate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 (syn-Carbonyl) | 10 (anti-Carbonyl) | 10' (anti-Carbonyl, chair-flipped) | |

| Stretch | 2.7039 | 2.6781 | 3.2067 |

| Bend | 12.6791 | 11.2770 | 16.2283 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.4468 | 0.3241 | 0.2760 |

| Torsion | 22.2395 | 20.7220 | 20.5803 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.7338 | -1.6410 | 1.1014 |

| 1,4 VDW | 14.2283 | 13.2121 | 13.9044 |

| Charge/Dipole | - | - | - |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.7020 | -2.0023 | -1.8249 |

| Total MM2 Energy | 48.8617 | 44.5701 | 53.4722 |

| MOPAC/PM6 (Heat of Formation) | -61.43821 | -65.07134 | -58.42948 |

| MMFF94 | 67.7648 | 60.5834 | 73.2899 |

| Geometry (*minimised with all the above) | |||

Following the isolation of the 3 possible conformations, and given the apparent effect of Non-VDW interactions arising from Hydrogen-bonding in these isomers, MOPAC and MMFF94 calculations were run on the MM2 optimized intermediates as an attempt to obtain a more precise measurement. This attempt is justified by looking at the methods and the nature of H-bonding, as both MOPAC and MMFF94 treat bonds significantly differently than MM2 in that their focus is put more on the electronic interactions rather than the classical two-body spring potential and other additive energy terms.

MOPAC/MMFF94

MOPAC and MMFF94 gave results that are similar to MM2 calculations, which is enough to say the MM2 method is good enough to reach a certain conclusion about the stability of the isomers at hand. Unfortunately it is not easy to point out how differently MMFF94 treats a system, since it was initially formulated privately for Merck Research company, however, by looking at the MMFF94 energy values of intermediates 9 & 10, it can be said that MMFF94 is more sensitive to such interactions, as the difference of MM2 energies of the said isomers is ≈4 kcal/mol, whereas MMFF94 gave a difference of ≈7 kcal/mol.

Hyperstable Alkenes

The literature on hyperstable alkene gives the major contribution to the stabililty of a bridgehead olefin to be the relative strain of the olefin itself and its parent hydrocarbon. This can be studied using optimization methods and inspecting the geometry/angles of the alkene and its hydrocarbon by comparison to their relative ideal geometries, namely sp2 and sp3.

| Parameter | Alkene/sp2 |  |

Parent Alkane/sp3 |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle (in degrees) | 123.1° | 118.6° | ||

| Ideal Angle for Given Geometry | 120° | 109.5° |

The results are given in Table 2.2. The angle was measured between the bond under study and the bridgehead carbon. It can be seen from the results that both structures are somewhat distorted from their ideal geometries, but it is evident that the alkane is under the most strain, as it adopts an sp3 geometry with an angle of 119°, which is significantly different than 109.5° whereas the alkene has to distort only slightly from an ideal angle of 120°.

Hence, said strain, or so its called, olefin strain, is the major parameter in explaining the nature of hyperstable alkenes, and their lowered reactivitiy towards functionalization when the alkene under study is part of a bigger ring structure suffering from a residual strain, such as a hydrocarbon bridge.

Semi-Empricial/DFT Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Outline

The carbenylation reaction of a chlorosubstituted aryl derivative (Compound 12) was studied using MOPAC calculations, focusing on electronic effects and Molecular Orbitals. The difference of the two alkene groups in Compound 12 were noted and along with this difference, their importance in the reactivity of the system was explained.

Results and Discussion

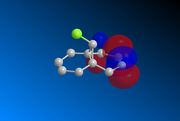

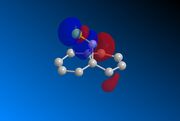

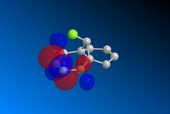

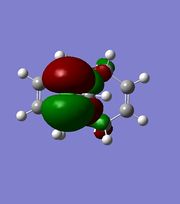

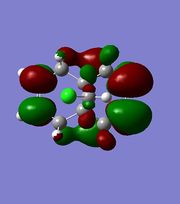

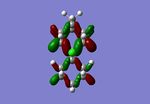

Compound 12 was drawn on ChemBio3D and its geometry optimised prior to any MOPAC calculations. The underlying HOMO/LUMO interactions obtained via the MOPAC minimisation of the compound in PM6 geometry are given below;

| Displayed Orbitals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 | |

| MOPAC/PM6 |  |

|

|

|

|

| Gaussview |  |

|

|

|

|

The orbitals displayed above minimised in MOPAC are seen to have incorrect symmetry in relation to the Cs. This is evidently a fault in the MOPAC program as it does not fully account for the plane of symmetry shown in the symmetry figure shown on the right. This problem can indeed be worked around by displaying the orbitals using Gaussview after running the compound file on SCAN. These are also given in Table 3.1, and can be seen to have the correct symmetry of the Cs point group.

Upon inspection of the HOMO, which is the obvious choice for any participation in nucleophilic attack, it can be seen that the syn/endo C=C that is on the side of the chlorine atom, has significantly larger electron density around it compared to the anti/exo C=C. Hence, one would expect a stronger nucleophilic character from the endo C=C, resulting in a regioselective carbenylation reaction, as seen in the figure showing the mechanism.

Hence, the different reactivities of the alkene groups can been explained by the endo C=C having more electron density in its HOMO, but this is not a full answer. Why does the exo C=C show less nucleophilic character than the endo? Intuitively, as well as looking at the LUMO+2(Gaussian), it is seen that the C-Cl bond has its anti-bonding σ*C-Cl orbital pointing towards the exo-alkene. Moreover, the exo-alkene was found to have most of its eletron density in the HOMO-1 level. Since the LUMO+2 and HOMO-1 have matching symmetries, as do all other orbitals, the exo-alkene can most likely donate its electron density into the C-Cl antibonding orbital. Moreover, upon minimisation, it was observed that the dihedral angle measured between the 4 carbon atoms of the exo and endo side was different by an angle of 20 ° (for endo; -1.3 °, for exo; 18.8 °). This indicates that the exo side is slightly bent towards the bridgehead, due to the aforementioned e- donation, and the endo side is slightly bent away from the C-Cl, which is probably due to electronic clashing from the HOMO’s. Hence, because σ*C-Cl is a good acceptor (low-lying antibonding orbital due to electronegative Cl), and πC=C is a good donor, the symmetrical HOMO/LUMO presence leads to an interaction, leading to the distorted geometry of Compound 12 and reduced nucleophilicity of the exo bond. [9]

Further Analysis

The πexo,C=C --> σ*C-Cl donation explains the geometry of the overall molecule, as well as its regioselective reactivity. The extent of this interaction has been studied by altering the nature of the exo-alkene bond to vary the magnitude of πexo,C=C --> σ*C-Cl electron donation. The bond strengths of the C=C bonds were measured, along with the corresponding C-Cl bonds using Gaussview software. The results can be seen in Table 3.2.

|

|

|---|

Intuitively, one would expect the C-Cl bond to weaken as the substituents on the exo-alkene became more and more electron donating, as this would mean more donation into antibonding C-Cl, therefore a decreased the bond order. Following this, electron withdrawing substituents on the alkene would mean the opposite; a stronger C-Cl bond arising from an increased bond order, which would reach its strongest when the alkene is absent as a whole. This is indeed what is observed, as the monoalkene exhibits a stronger C-Cl bond compared to the dialkene by 9 cm-1. The electron withdrawing substituent CN results in a stronger C-Cl bond, and the electron donating substituent SiH3 gives a weaker C-Cl bond. Hence, this gives rise to the tuneability of the C-Cl bond, which can be said to depend heavily on the exo-alkene, which in turn can be tuned by substituent effects.

Baeyer-Villiger Reaction of a Substituted-Norbornanone: An Analogous Example

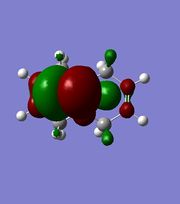

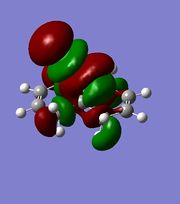

A similar substituent effect can be observed in the Baeyer-Villiger reaction of norbornan-7-one. In the reaction mechanism given in the figure on the right, it is found that when R=CN, an electron withdrawing group, the reaction shows high regioselectivity and gives the product as Product 2 (Prod.2 100:0 Prod.3).[10] However, prior to the formation of the products, the literature Baeyer-Villiger reaction predicts the formation of a tetrahedral intermediate arising from the peroxy-attack on the ketone. The attack of such a nucleophile gives way to the first regioselective process in the reaction, which can be explained by a similar MO analysis as the carbenylation mechanism. The orbitals are given below

|

|

|

|---|

It can be seen that in the LUMO+1 orbitals the endo-side(the CN side) has a larger anti-bonding orbital(green), which would gives rise to the tetrahedral formation in the endo-side. The reaction is then dictated via the transition state energies from the migratory aptitude of each either C-C=O bond.

Glycosidation: Computational Approach

Anomers: Outline

In pyranose-like species bearing a heteroatom within the ring structure, the position of the substituent adjacent to the heteroatom may either be equatorial or axial. Generally, the equatorial position for substituents other than hydrogen is preferred since it leads to the least hindrance. However, the anomeric effect, which was first observed in 1955, gives this substituent in the axial position(α-anomer), which could be explained by the arising stereoelectronic effects that are described below.

The anti-periplanar relationship between the anomeric substituent and the lone pair on the ring oxygen in the α-anomer gives rise to the possibility of lone pair donation from the heteroatom oxygen into the antibonding σ* orbital of the anomeric substituent. The donation is analogous to resonance, which is long-known to stabilise a molecule. This relationship is absent in the β-anomer, as the orbitals are neither syn nor anti periplanar, which is the counter-argument as to why this anomer is not preferred in pyranose ring structures. However, a pseudo-long-range substituent effect has been observed in such ring structures which leads to the formation of the β-anomer. When the carbon adjacent to the anomeric carbon, C(1), has an acetyl group, neighbouring group participation leads to the quenching/stabilising of the oxonium cation formed from the aforementioned resonance. Upon nucleophilic attack, this quenched structure limits the approach of the incoming nucleophile, giving the β-anomer via a reverse-anomeric effect. This phenomenon is studied. [11]

MM2/MOPAC?: Choosing the appropriate method

Prior to analysis of the results, the role of MM2 calculations in this system should be made clear. Because the electronic interactions are important in the system(A and B), especially beyond the point where the oxonium cation is quenched by neighbouring group participation (C and D), the total MM2 energies start becoming more and more unreliable, and hence should be treated as less important compared to values obtained from MOPAC/PM6 calculations. The difference between these two methods have been discussed before, however a quick overview will be given and parameters discussed in the said context.

The weakness of Alligner’s MM2 Force Field in this case can be seen as its inability in characterising the oxonium cation as one, which is a non-classical cation and can easily be confused with a hypervalent ether. Following upon this argument, the cationic charge on the oxygen has to be defined manually prior to any minimisation. However, this is not a weakness of the MM2 Force Field per se, but ChemBio itself, as other methods of minimisation tend to oversee this charge as well, with the only exception being MOPAC.

Generally, MOPAC method relies mostly on the number of electrons given in the system, hence it is immune to any possible confusions that may have been had about the characteristics of a pre-defined bond. Hence, MOPAC calculations are a better fit to this system, and more focus will be put on these energy values than Alligner’s MM2 Force Field.

Results and Discussion

The R group has to be defined before minimising the structure. For the sake of the argument, one could talk about a range of substituents, however it is only intuitive to give the hydrogen atom as a starting point. This –OH group could very well keep the computational demand minimal, however it has been previously discussed in the Taxol argument that hydrogen bonding is a dominant phenomenon in energy calculations and hence can cause significant deviance on the total energy value. Moreover, adding a heteroatom that is not already present in the system would cause further demand, hence the best choice for R would be a methyl –CH3 group.

4 conformations were found in total for the A & B pair, where the initial A and B pair were already given as the neighbouring group occupying the equatorial and axial positions respectively, and hence limiting the incipient nucleophile attack to top and bottom face. The A’ & B’ pair are defined as the complementary conformations of their parent pair, where A has been ring-flipped to give A’ with the neighbouring group occupying the complementary axial position, limiting nucleophilic attack to the bottom, and vice versa for B & B’. These conformations have been minimised in energy using MM2 followed by the MOPAC/PM6 method. The results and the geometries are given in Table 4.1.

| Method(MM2/MOPAC) (energy in kcal/mol) | Reactant (AA'BB') | Intermediate (CC'DD') | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A

|

A'

|

B

|

B'

|

C

|

C'

|

D

|

D'

| ||

| MM2 | Stretch | 2.2046 | 2.2486 | 2.3387 | 2.4539 | 2.0479 | 2.9294 | 2.0574 | 1.8804 |

| Bend | 10.3481 | 13.9799 | 11.6914 | 2.4539 | 13.37 | 18.08 | 16.4047 | 20.3017 | |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.8082 | 0.9579 | 0.9504 | 1.0561 | 0.7817 | 0.8788 | 0.95 | 1.0099 | |

| Torsion | 3.0736 | 0.643 | 1.3036 | 2.6115 | 9.765 | 9.263 | 9.6157 | 9.1985 | |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.8021 | -1.9382 | -2.2974 | -2.8078 | -3.8688 | -3.0253 | -3.9439 | -1.8378 | |

| 1,4 VDW | 19.6709 | 18.66 | 18.5641 | 18.8504 | 17.7011 | 19.2546 | 17.1781 | 15.8836 | |

| Charge/Dipole | -15.6068 | -12.2774 | -11.2677 | -1.0594 | -2.2124 | -1.065 | 4.8558 | -8.8456 | |

| Dipole/Dipole | 7.0548 | 8.7099 | 6.5958 | 6.603 | -2.2208 | -0.9585 | -1.7048 | -1.3089 | |

| Total MM2 Energy | 24.7514 | 30.9838 | 27.8788 | 42.1717 | 35.3636 | 45.3569 | 45.413 | 36.282 | |

| MOPAC/Heat of Formation | -91.177 | -75.907 | -85.528 | -64.082 | -91.650 | -66.726 | -85.945 | -64.052 | |

It was concluded before that MOPAC calculations were more reliable than MM2 ones, however, both of these methods give similar results when just dealing with the first two isomers and their derivatives, AA’BB’.

It can be seen that the A’B’ pair are significantly higher in energy than the AB pair, indicating that ring-flipping is highly unfavourable, possibly due to the axial strain achieved through having all the substituents close together. Moreover, beyond ring flipping is where the MM2 calculations are expected to fail, as all the substituents have significant proximity and classical methods no longer apply. Among the initial AB pair, A seems to be lower in energy compared to B by ≈ 3 kcal/mol (MOPAC/PM6 method), which means the neighbouring group participation from the acetyl group would most likely direct nucleophilic attack to the top face, hence giving the β-anomer. The lower energy can be explained by the charge/dipole interaction included in MM2 calculations, as this is what dictates as the proximity of the acetyl carbonyl and the (+) oxonium charge changes. Of course this can change, as the effect is dependent on a number of factors, such as the nature of the ring-substituents and the extent of stabilisation of an axial atom from the ether oxygen via nLp,O-->σ*substituent donation, which would vary the magnitude of the cationic charge. Moreover, since the energy difference is relatively small between A & B, at a temperature slightly higher than room temperature, the reaction should give both anomers as the product.

Furthermore, it is important to talk about the intermediate energies before reaching a viable conclusion, as a lower energy intermediate might cause a shift between structures, given the possibility of a rearrangement, which would also lead to a mixed product. The observation made for the AA’BB’ pairs are seen again in the C’D’ pairs as they are significantly higher in energy than their parent structures. Hence, ring-flipping is again highly unfavourable. Moreover, the similarity between A&C and B&D in terms of their energies should be noted. The MOPAC energy of A and C are almost equal, as are the energies of B and D, which has to be explained. Since the formation of the intermediate structures are driven by a present charged species, they are merely resonant forms of each other, and in theory are equal in energy. The difference between MOPAC and MM2 really does come to surface here, as MM2 fails to recognize this equality, whereas MOPAC does due to all of the aforementioned reasons. Both MOPAC minimisations give the acyl oxygen close to the ideally preferred Burgi-Dunitz angle(105.1θ, view in PM6 jmol), which is expected as the mecanism is analogous to nucleophilic attack on a sp2 hybridised carbonyl. This is again seen in B & D pairs. MOPAC, unlike MM2, treats molecule in a more flexible way as it will assume new bonsd as it sees fit. Hence, the resonance form is present in all the MOPAC calculations, which is the reason why A=C and B=D. However, the A’B’C’D’ pairs seem to not fully apply in this methods, as the results could not be explained fully by just analysing the values. Instead, the stabilities could be related to their geometries by intuition, where the axial nature of the ring-flipped structures would cause much strain, especially in C’ and D’, since the formation of a rigid bond between the acyl oxygen puts high strain/bend/torsion energy against the rigid ring-backbone.

Mini Project: Thermolysis of 1-chlorodiadamantane

Adamantane: A Brief Background and Outline

Adamantane can be said to be unique in terms of its nature, as its structure resembles diamond in that it is rigid and yet stress-free. It is a stable species with a higher melting point than other hydrocarbons its molecular weight. It can be obtained from the hydrogenated cyclopentadiene dimer species discussed in section 1. It was first synthesised by Meerwein in 1924. The molecule is not chiral, however it can be made chiral if all the four vertices of the structure bears a different substituent. This won't make any specific carbon a chiral center per se, but the overall chirality of the molecule will be made present. This is not the case in this study, hence an optical rotation will not be run on the compound. [12] [13]

The Thermolysis Reaction: Outline

"Thermal rearrangement of 1-substituted spiro [ adamantane-2,2'- 1 1 adamantane] derivatives"

The thermal rearrangement of 1-halosubstituted-diadamantane was studied. Using chlorine as the halogen, the thermolysis reaction at temperatures higher than ~275 gives either the 4-chloro-substituted or the 6-chlorosubstituted diadamantane, where the former has 2 stereoisomers, namely 4-anti-chlorodiadamantane and 4-syn-chlorodiadamantane (display available in tables). The literature discounts the 6-chloro species due to symmetry issues, hence only the 4-chloro-diadamantane isomers will be investigated.[14] [15] [16] Possible spectroscopical results (IR, NMR) were obtained using Gaussian calculations, and MM2/MOPAC energies were obtained from ChemBio3D using Gaussian optimised geometries.

Results and Discussion

13C NMR was cited in the literature paper, and was used to confirm the thermolysis reaction. The literature does not distinguish between the two isomers, and that is the objective of this study; which 4-chlorodiadamantane isomer is more likely to form upon thermolysis of 1-chlorodiadamantane? Moreover, the compounds at hand are neither chiral(discussed in the previous sections), nor UV-active hence only NMR and IR spectroscopy were run and analysed.

NMR Spectroscopy

The essential difference in the two isomers (anti/syn) is the conformation arising from the position of the chlorine atom, which may or may not give peaks distinctive to each isomer. It is more useful to compare MM2/MOPAC energies, however an NMR interpretation will be given.

The issue of whether the computational models are in accord with the actual molecules was dealt with by predicting a C13 NMR spectra of the molecule using the GIAO method and comparing the computational data with the experimental, which were published in the literature paper. The two sets of values (computational data, literature data) for each compound under study are given below in Table 5.1.

| Peak Type/Environment | 1-chlorodiadamantane [17]

|

Peak Type/Environment | 4-syn/anti-chlorodiadamantane [18]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C Peak Shift (δ,ppm) | 13C Peak Shift (δ,ppm) | ||||||

| Results | Literature (solvent: CDCl3) [19] | Discrepancy | Results | Literature (solvent: CDCl3)[20] | Discrepancy | ||

| C-Cl (correction: -3 ppm) | 81.9 (corrected from 84.9) | 78.5 | 3.4 | CHCl (correction: -3 ppm) | 68.0 (corrected from 71.0) | 65.2 | 2.8 |

| Cq | 51.6 | 48.3 | 3.3 | Cq | 47.6 | 44.4 | 3.2 |

| 2 CH | 46.4 | 46.3 | 0.1 | CH | 40.4 | 39.1 | 1.3 |

| CH | 40.7 | 41.1 | 0.4 | CH | 39.1 | 38.1 | 1.0 |

| CH | 38.5 | 37.1 | 1.4 | CH | 36.9 | 35.2 | 1.7 |

| CH | 37.5 | 35.8 | 1.7 | CH | 33.6 | 32.4 | 1.2 |

| 2 CH2 | 34.6 | 33.8 | 0.6 | CH | 33.3 | 32.3 | 1.0 |

| 2 CH | 34.3 | 33.5 | 0.8 | CH | 33.3 | 32.1 | 1.2 |

| 2 CH | 33.6 | 31.7 | 1.9 | CH | 32.9 | 31.8 | 1.1 |

| 2 CH | 33.4 | 31.5 | 1.9 | CH | 32.9 | 31.8 | 1.1 |

| 2 CH | 31.4 | 30.3 | 1.1 | CH | 32.9 | 31.6 | 1.3 |

| CH | 28.9 | 27.7 | 1.2 | CH | 32.7 | 31.5 | 1.2 |

| CH | 28.8 | 27.0 | 1.8 | CH | 32.6 | 30.6 | 2.0 |

| - | - | - | - | CH | 32.6 | 30.3 | 2.3 |

| - | - | - | - | CH | 31.8 | 29.2 | 2.6 |

| - | - | - | - | CH | 29.1 | 27.4 | 1.7 |

| - | - | - | - | CH | 28.9 | 27.3 | 1.6 |

| - | - | - | - | CH | 28.2 | 26.7 | 1.5 |

| - | - | - | - | CH | 26.3 | 24.3 | 2.0 |

The NMR results were in good argument with the literature values, as the discrepancy of the shift are only off by ~ 2-3 ppm. This corresponds to average discrepancy is value of 1.6 ppm, which is a neglectable error. The C-Cl shifts had to be corrected since over-prediction of the shifts of heavy-atom bonds is common in the system.

The NMR is satisfactory in determining whether a thermal rearrangement is indeed present in the species at high temperatures, as the C-Cl shift in 1-chlorodiadamantane and 4-anti/syn-diadamantane evidently indicates they are in different environments. However, the syn/anti isomers both gave similar results, where the paek shifts of the -anti isomer were slightly more deshielded overall. This similarity was expected as they are diastereoisomers of each other and exhibit identical connectivity. NMR can only provide so much information about the nature of the isomers, hence other methods are needed to be sought.

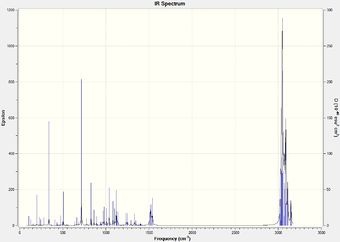

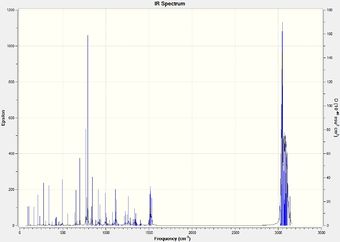

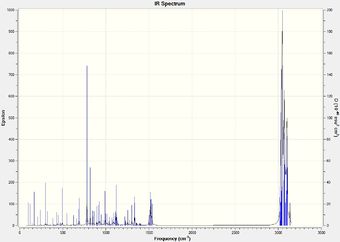

IR Spectroscopy

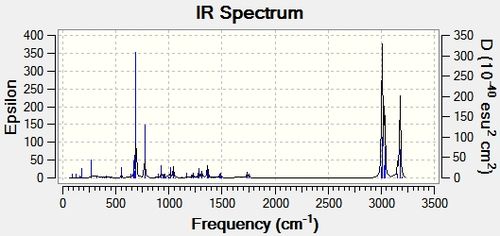

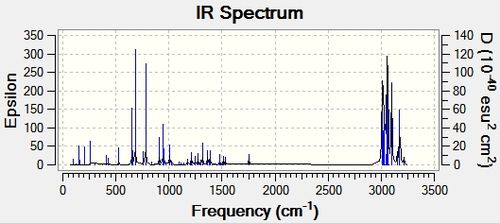

IR frequency values were not cited in the literature paper, however the Gaussian calculations gave promisingly different values for the isomers. These can be seen in Table 5.2 along with the displayed C-Cl stretches.

|

|

|

|---|

It is seen that the C-Cl bond in the thermolysis product is stronger than the reactant, 1-chlorodiadamantane by a difference of ~ 70 cm-1. This is a significant difference, and may contribute to the overall stability of the thermolysis products, given they are more than just high energy intermediates. The two isomers, 4-anti/syn-chlorodiadamantane, exhibit different C-Cl bond stretch frequencies, with the –anti isomer having a stronger C-Cl stretch frequency by 10 cm-1. This is intuitive, as the C-Cl bond in the –anti isomer points away from the molecule and can stretch without suffering from steric clashes with the nearby hydrogens. In other words, it has more freedom to vibrate. The limiting steric effects of the overall structrue are observed in the –syn isomer, as the C-Cl peak is less sharper and weaker. This is displayed in Table 5.2.

Another thing to mention is that the C-C bonds gave weak peaks, if any, in the IR spectrum. Since adamantane suffers from a high strain due to the bridged-ring structure, all the C-C bonds are tertiary and are contained within this strained ring-structure. Hence, in the context of adamantane, the C-C bonds can be said to be intrinsically weak, and do not vibrate/stretch easily compared to alkyls.

MM2/MOPAC Calculations

The IR spectrum gave promising results that somewhat distinguished between the two isomers with respect to their bond strengths. Following from this, if this greater C-Cl bond strength is ubiquitous in the overall bond frequencies of the –anti isomer, it can be predicted that this is the stable isomer compared to the -syn and will be the observed isomer upon thermolysis. The MM2/MOPAC calculations were run on ChemBio3D using the PM6 geometries optimised by Gaussian priorly. The results are given below.

| Method (energy in kcal/mol) | 1-chloro

|

4-anti-chloro

|

4-syn-chloro

| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM2 | stretch | 5.3464 | 3.9132 | 4.0693 |

| bend | 7.7720 | 4.5386 | 6.0187 | |

| stretch-bend | 0.7308 | 0.4755 | 0.5195 | |

| torsion | 20.1056 | 19.7734 | 20.0805 | |

| Non-1,4 VDW | 0.0467 | -2.4838 | -2.1161 | |

| 1,4 VDW | 21.0067 | 19.7571 | 19.7838 | |

| Charge/Dipole | - | - | - | |

| Dipole/Dipole | - | - | - | |

| Total MM2 Energy | 55.0081 | 45.9740 | 48.3557 | |

| MOPAC/PM6 | -60.90956 | -63.77747 | -60.84033 | |

The parameters will be analysed. The lower stretch/bend/stretch-bend energies of the -anti isomer confirms the IR predictions, as the order of compounds in decreasing MM2 stretch/bend energies give 1-chloro > 4-syn > 4-anti, which is also obtained from the increasing IR C-Cl bond stretch frequencies. Hence, the contribution from the C-Cl bond strength to the overall molecule is an important defining parameter in the stability of the isomer. Furthermore, it is observed that the thermally rearranged isomers have lower Non-1,4 VDW/1,4 VDW values, which again indicates that the 4-position for the chlorine atom is electronically more favourable.

The total MM2 energy values are defining. It is seen that 1-chlorodiadamantane has the highest energy amongst the 3 compounds under study, which indicates that it indeed can be viewed as a high energy intermediate in the context of a total synthesis of the 4-chloro isomers. 4-anti-chlorodiadamante is indeed the stable isomer as initially predicted from IR values, by a total MM2 energy value of ~ 45 kcal/mol. The high energy barrier requires the process to be carried at high temperatures, which would give the 4-anti-chlorodiadamantane as the product. At low temperatures, 1-chlorodiadamantane would be stable.

Since electronic effects are non-dominating in this case, MM2 provides good enough information and is reliable, however, even though it doesn’t distinguish between 1-chloro and 4-syn-diadamantane, MOPAC/PM6 also gives a sufficient answer in determining the –anti isomer as the stable one, with a heat of formation value of ~ -63 kcal/mol.

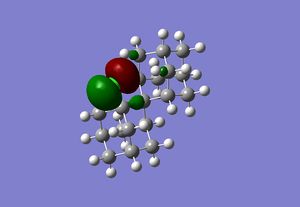

The relevant molecular orbitals have been calculated with the appropriate method used in the carbenylation section, and the HOMO and HOMO-4 are given for reference. The compound has Cs point group, and this can be viewed clearly in the HOMO-4 level, where the plane of symmetry can be compared to the chloro-substituted bicyclic dialkene.

Making sense of the thermolysis reaction using molecular orbitals is not intuitive, and is quite obscure given that most of the orbitals are spread out over the entire molecule. Moreover, it is not certain that such an interaction is orbital-driven, since MM2 energies were proved more useful then MOPAC. However, a mechanism can be proposed and supported with MO calculations. It is possible that the rearranged chlorine does not stay within the initial adamantane unit it was in upon thermal rearrangement. A possible mechanism is given below, where the chlorine "jumps" to the other adamantane unit which upon rotation is the 4-chlorodiadamantane species. This is a plausible mechanism, as the proximity is enough for the chlorine HOMO to attack. Upon displaying the orbitals, it was seen that the HOMO of 1-chlorodiadamantane lies on the C-Cl bond, and it pointed towards the possible rearrangement site given in the figure. This orbital also causes the intrinsic Cl distortion in the species, which is again seen in the figure.

Conclusion

5 systems have been studied. A concerted pericyclic dimerization reaction and a system showing atropisomerism using MM2 Force Field and Molecular Mehcanics as the main focus, and a regioselective carbenlyation reaction and anomeric glycosidation reaction using semi-empirical molecular orbital theory, and in the end, a diadamanate structure using spectroscopical method obtained from computational ab initio/DFT methods. The discrepancy of the results in the mini project have been accounted for. The stabilities of each system have been explained using the dominant parameters, and the parameters discussed with respect to the strengths and weaknesses of the different methods.

References

- ↑ Wu, Zhijun. Lecture Notes on Computatlonal Structrual Biology, World Scientific Publishing, 2008.

- ↑ Allinger NL, Burkert U (1982). Molecular Mechanics. An American Chemical Society Publication. ISBN 0-8412-0885-9

- ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:organic

- ↑ The Diels–Alder Reaction in Total Synthesis K. C. Nicolaou, S. A. Snyder, T. Montagnon, G. Vassilikogiannakis Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1668–1698. (Review) doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1668::AID-ANIE1668>3.0.CO;2-Z

- ↑ Clayden, J., Greeves, N., Warren, S., Wothers, P., "Organic Chemistry", 2001

- ↑ Wilhelm F. Maier, Paul Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891. DOI: 10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ J. G. Vinter and H. M. R. Hoffman, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1974, 96, 5466 (DOI:10.1021/ja00824a025 DOI:10.1021/ja00824a025

- ↑ Nicolaou, KC; Yang, Z; Liu, JJ; Ueno, H; Nantermet, PG; Guy, RK; Claiborne, CF; Renaud, J et al. (February 1994). "Total synthesis of taxol". Nature 367 (6464): 630–4. doi:10.1038/367630a0. PMID 7906395

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ Konigsberger, "Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of bicyclic ketones by Cylindrocarpon destructans." Doi: 10.1007/BF01086344

- ↑ D. M. Whitfield, T. Nukada, Carbohydr. Res., 2007, 342, 1291. DOI:10.1016/j.carres.2007.03.030

- ↑ J. Applequist, P. Rivers, D. E. Applequist. (1969). "Theoretical and experimental studies of optically active bridgehead-substituted adamantanes and related compounds". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 91 (21): 5705–5711. doi:10.1021/ja01049a002

- ↑ H. Hamill, M. A. McKervey (1969). "The resolution of 3-methyl-5-bromoadamantanecarboxylic acid". Chem. Comm. (15): 864. doi:10.1039/C2969000864a

- ↑ J. J. Sosnowski, A. L. Rheingold and R. K. Murray, J. Org. Chem., 1985,50,3788.

- ↑ J. S. Lomas, C. Cordier and S. Briand, “"Thermal rearrangement of 1-substituted spiro [ adamantane-2,2'- 1 1 adamantane] derivatives" J. Chem. SOC., Perkin Trans. 2, 1996

- ↑ J. S. Lomas, C. Cordier and S. Briand, J. Chem. SOC., Perkin Trans. 2, 1996, preceding paper.

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11800

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11801

- ↑ J. S. Lomas, C. Cordier and S. Briand, “"Thermal rearrangement of 1-substituted spiro [ adamantane-2,2'- 1 1 adamantane] derivatives" J. Chem. SOC., Perkin Trans. 2, 1996

- ↑ J. S. Lomas, C. Cordier and S. Briand, “"Thermal rearrangement of 1-substituted spiro [ adamantane-2,2'- 1 1 adamantane] derivatives" J. Chem. SOC., Perkin Trans. 2, 1996

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11802

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11803

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11804