Rep:Mod:eh1013

This computational experiment looks at the study of transition structures from reactions belonging to a class of reactions called pericyclics: the Cope rearrangement and Diels-Alder cycloaddition. From transition state optimisations, the reaction pathways and activation energy barriers can be investigated and rationalsed. All optimisation calculations carried out during the course of this experiment were performed using GaussView 5.0.

Introduction to Pericyclic Reactions

Pericyclic reactions are so-called due to the adoption of a cyclic transition state geometry during a concerted reaction. The reactivity of such reactions can be predicted using Woodward-Hoffmann analysis. For a thermal pericyclic reaction, the Woodward-Hoffmann rules state that:

The total number of (4q + 2)s and (4r)a components must be odd.[1]

where 'q' and 'r' are non-zero integers, and the subscripts 's' and 'a' stand for 'suprafacial' and 'antarafacial', respectively. A suprafacial component is one where the reactive orbitals partaking in the bond formation are on the same side of the molecule. In contrast, an antarafacial component combines orbital lobes from opposite sides.

The rules are different for a reaction to be photochemically allowed; the total must be even rather than odd, but in the realms of this experiment it is only thermal reactions we are considering.

Nf710 (talk) 16:27, 4 February 2016 (UTC) Good understanding of the mechanism

Gaussian Computational Methods

There are different computational methods available within Gaussian; a combination of two methods have been used for this experiment: Hartree-Fock (HF) and Density Functional Theory (DFT), which are quantum mechanical modelling methods used to solve the Schrödinger equation. DFT is useful for its computational cheapness in investigating the electronic ground state of molecules compared to HF. There are also different basis sets to utilise. 3-21G and 6-31G* were used, 6-31G* being the more 'expensive' of the two. These are known as 'split-valence' basis sets, which means that each valence orbital is made up of more than one basis function, allowing it to adjust to different molecular environments. The notation of the basis sets was developed by John Pople. They follow a general formula of X-YZG where 'X' dictates the number of Gaussian bell functions used to build the core atomic orbital basis function, and 'Y' and 'Z' represent the number of Gaussian functions used in the linear combination of each basis function.[2] The '*' in the 6-31G* basis set refers to the addition of extra orbitals within the calculation which account for molecular orbital polarisation.

Nf710 (talk) 16:33, 4 February 2016 (UTC) Good understanding however you could have gone into more detail with the understanding of the method themselves

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

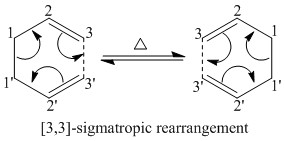

The Cope rearrangement has incurred some controversy in the past in relation to how its mechanism proceeds; whether it's in a concerted, step-wise or dissociative fashion. It is now widely agreed upon that the mechanism is concerted.[3] This reaction is also known as a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, named according to the carbon atom numbers where the new sigma bond forms with respect to the corresponding sigma bond that is broken (as shown in figure 1).

The sigmatropic rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene passes through either a 'boat' or 'chair' transition state. Computational optimisations performed on these transition state geometries allow us to interpret which structure is energetically favourable, as well as which reactant conformers (gauche or anti) facilitate the lowest energy reaction pathway.

Optimising Reactants and Products

The free rotation about an sp3 hybridised carbon centre allows for a great number of possible conformers to form the reactant and product in the Cope rearrangement. Two anti and two gauche conformers of 1,5-hexadiene have been optimised and compared using the Hartree-Fock method with a 3-21G basis set:

Anti1 Conformer

By drawing an antiperiplanar conformation (dihedral angle of 180 °) of 1,5-hexadiene in GaussView and 'cleaning' the molecule using the in-built clean function, a more accurate representation of the intended structure is generated before running an optimisation. If a molecular optimisation is attempted whilst the starting geometry is too far from the geometry you're trying to produce then the Gaussian calculation is more likely to generate a molecule at an energy minimum that does not correspond to the anticipated conformer. After cleaning, the molecule still needs to be optimised as it's only an approximation. From HF/3-21G, the energy obtained for anti1 was -231.69260235 Hartrees, with a point group of C2.

| Summary Data | GaussView Structure | Point Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C2 |

Gauche1 Conformer

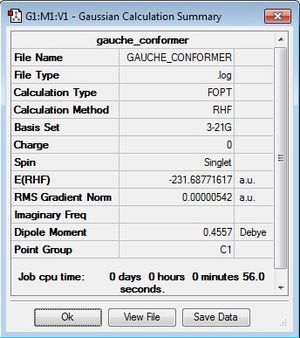

Gauche conformers have a dihedral angle of 60 ° and would therefore be expected to be the higher energy conformer compared to anti as a result of greater steric clash between substituents. This is indeed true for the gauche1 conformer computed in this example. After cleaning and optimising at the HF/3-21G level of theory, the energy was found to be -231.68771617 Hartrees and the point group is C2.

| Summary Data | GaussView Structure | Point Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C2 |

Gauche3 Conformer

After optimisation, the energy obtained was -231.69266120 Hartrees, this time belonging to the point group C1.

| Summary Data | GaussView Structure | Point Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C1 |

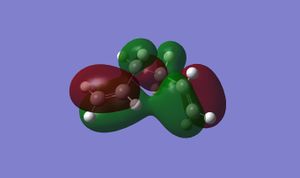

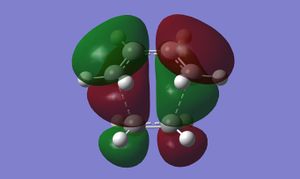

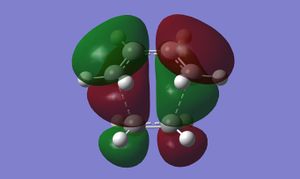

Surprisingly, at least from a steric view-point, this is the lowest energy conformation. One rationale for this observation is that favourable second order orbital interactions in the gauche3 conformer lower its energy minimum. This phenomenon can be seen in the HOMO of the gauche3 conformer:

There is considerable orbital overlap between the terminal pi-bonds here, which is a stabilising interaction.

Nf710 (talk) 16:36, 4 February 2016 (UTC) Good use of the orbitals to show the stabalisation

Anti2 Conformer

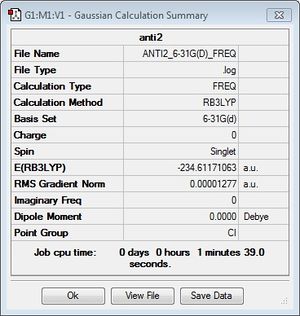

This conformer produced an energy of -231.69253527 Hartrees at the HF/3-21G level, and is of the point group Ci. The anti2 conformer was reoptimised at the higher level of theory, DFT/B3LYP/6-31G*. The energy obtained from this calculation (-234.61171063 Hartrees) is not comparable to that from HF/3-21G as it is meaningless to compare energies from different levels of theory. The DFT optimisation, generally speaking, is cheaper as well as being more precise than HF, as it takes into account the electron spin and pairing energies. However, with a larger basis set this process can be rather expensive.

| Summary Data | GaussView Structure | Point Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ci |

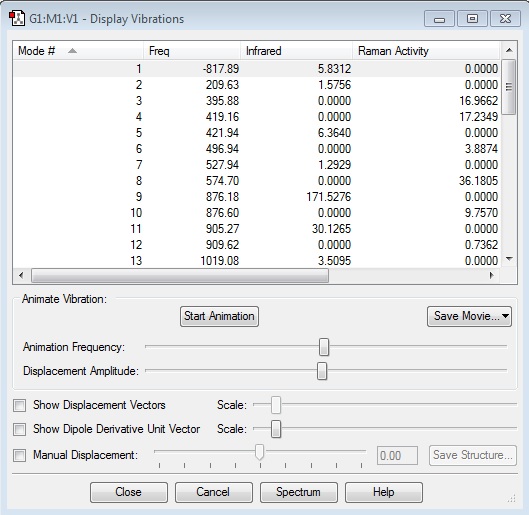

In order to confirm that the energy minimum has indeed been located, a frequency analysis was performed; an energy minimum has been reached if all vibrational frequencies are real and positive. The following table summarises the geometric similarities/differences between the anti2 conformer optimised at both levels of theory:

| Theory Level | Bond Length/ Å | Dihedral Angle/ ° | Point Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1=C2/C5=C6 Termini | C2-C3/C4-C5 | Central C3-C4 | C1-C2-C3-C4 | ||

| HF/3-21G | 1.355 | 1.540 | 1.540 | 114.67 | Ci |

| DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* | 1.334 | 1.504 | 1.548 | 118.60 | Ci |

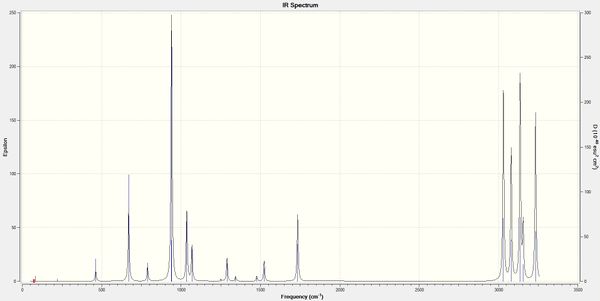

By viewing the IR spectrum (left), we can confirm that there are no negative (imaginary) frequencies and the intended real conformer has been achieved, rather than a transition state.

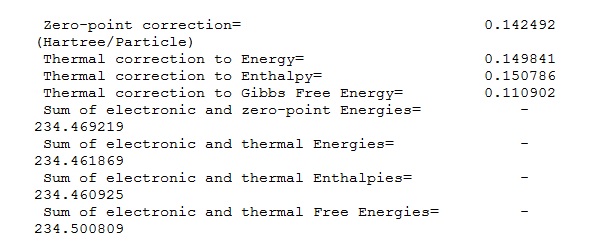

From the log file of the frequency analysis performed with the 6-31G* basis set, thermochemistry data for the molecule can be obtained, as follows:

The sum of electronic and zero-point energies is equivalent to the potential energy at zero Kelvin, including the zero-point vibrational energy:

E = Eelec + ZPE

The sum of electronic and thermal energies is the energy at 298.15 K and 1 atm, including contributions from translational, rotational and vibrational energy modes:

E = E + Evib + Erot Etrans

The sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies accounts for an additional correction for RT:

H = E + RT

The final energy sum for electronic and thermal free energies includes the entropic contribution to free energy:

G = H - TS

Optimising the 'Chair' and 'Boat' Transition Structures

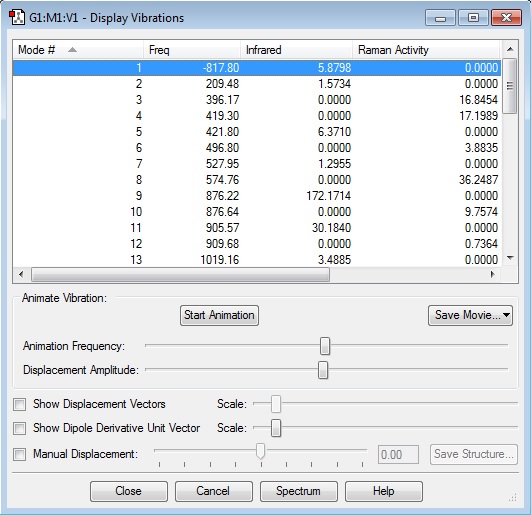

When locating the transition state of a molecule, the geometry is at a minimum energy when all of the vibrational frequencies are positive except for one, which is known as the imaginary freqency. The transition structure lies at the saddle point on the potential energy surface, and the second derivative (force constant, k) of the potential energy surface is negative, which gives rise to the imaginary frequency.

Computing Force Constants

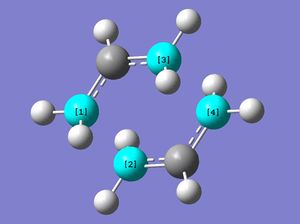

For the chair transition state computed using HF/3-21G and optimised to a Berny TS, the resulting electronic energy is -231.61932220 Hartrees, and the imaginary frequency occurs at -817.80 cm-1:

| Summary Data | GaussView Structure | Calculated Frequencies | Transition State Animation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Frozen Coordinate Method

An alternative method for locating the TS is the frozen coordinate method, which, in this example, fixes the intermediate bond forming/breaking distances to 2.2 Å before the final optimisation. This produces only minor differences in energy and geometry to the Berny TS method, summarised in the following table:

| TS Optimisation Method | Energy/ Hartrees | Imaginary Frequency/ cm-1 | Intermediate Bond Forming Distances/ Å | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1-C2 | C3-C4 | |||

| Berny TS | -231.61932220 | -817.80 | 2.02002 | 2.02002 |

| Frozen Bond | -231.61932233 | -817.89 | 2.02072 | 2.02075 |

The difference in results between these two methods is negligible, hence all subsequent optimisations have been performed using the Berny (or QST2, explored later) TS method, for consistency.

| Summary Data | GaussView Structure | Calculated Frequencies | Transition State Animation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

QST2 Method

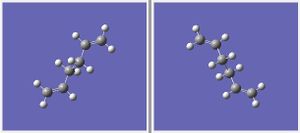

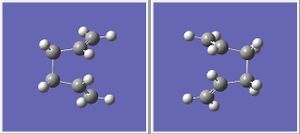

From the QST2 TS method, the boat TS energy minimum is -231.60280247 and the imaginary frequency occurs at -840.00 cm-1, which is animated below:

The initial optimisation of the boat TS was unsuccessful, owing to the fact that the reactant and product geometries were too far away from the anticipated boat structure. To fix this, the dihedral angles were adjusted in the reactant and product molecules before running the QST2 optimisation again:

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Analysis

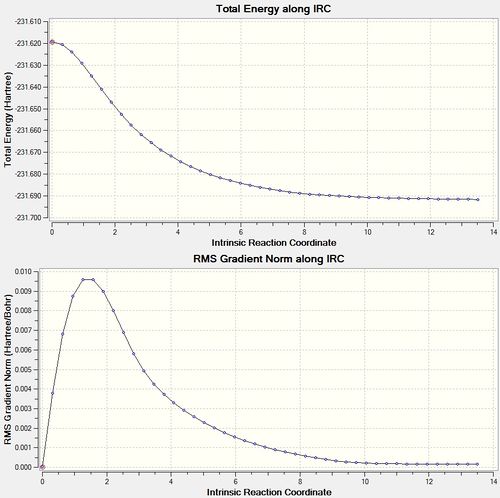

Running an IRC allows the reaction pathway to be visualised, and ultimately determines which conformers connect the transition state. As the reaction pathway for the Cope rearrangement is symmetric, it is not necessary to run an IRC in both directions, and hence only the forwards direction is shown graphically in the following examples. The IRC performed on the optimised chair TS terminated after 44 steps, and the energy can be seen to converge as the gradient tends to zero:

| IRC Plot | Reaction Path Animation |

|---|---|

|

|

The energy obtained from the resulting structure, when optimised, is -231.69166702 Hartrees. This is indicative of the gauche2 conformer, and also has the point group C2.

The IRC of the boat TS terminated after 75 steps and can be seen to reach the geometry of the lowest energy conformer, gauche3, with an energy (when optimised) of -231.69266121 Hartrees. Its point group of C1 is also consistent with gauche3.

| IRC Plot | Reaction Path Animation |

|---|---|

|

|

Nf710 (talk) 16:56, 4 February 2016 (UTC) Correct congf well done

Activation Energies

| Electronic Energy

(HF/3-21G)/ Hartrees |

Electronic + Zero-Point Energies (0 K)

(HF/3-21G)/ Hartrees |

Electronic + Thermal Energies (298.15 K)

(HF/3-21G)/ Hartrees |

Electronic Energy

(B3LYP/6-31G*)/ Hartrees |

Electronic + Zero Point Energies (0 K)

(B3LYP/6-31G*)/ Hartrees |

Electronic + Thermal Energies (298.15 K)

(B3LYP/6-31G*)/ Hartrees | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair TS | -231.61932220 | -231.466699 | -231.461340 | -234.55690813 | -234.414915 | -234.408975 |

| Boat TS | -231.60280247 | -231.450930 | -231.445301 | -234.54309340 | -234.402342 | -234.396007 |

| Anti2 Conformer | -231.69253527 | -231.539540 | -231.532566 | -234.61171063 | -234.469219 | -234.461869 |

| HF/3-21G

Activation Energy at 0 K/ kcal/mol |

HF/3-21G

Activation Energy at 298.15 K/ kcal/mol |

B3LYP/6-31G*

Activation Energy at 0 K/ kcal/mol |

B3LYP/6-31G*

Activation Energy at 298.15 K/ kcal/mol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair TS | 45.708 | 44.695 | 34.076 | 33.191 |

| Boat TS | 55.604 | 54.760 | 41.966 | 41.329 |

An important observation from these results is that the use of a higher basis set does not make a considerable difference to the geometric qualities of a molecule, but does greatly affect the computed activation energies.

Nf710 (talk) 16:58, 4 February 2016 (UTC) Correct energies and well evaluated. In general this a good report but you could have shown more understanding of what is going on with the quantum chemistry methods. and also you did compare the energies to experiment

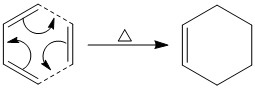

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels-Alder (DA) reaction, as mentioned before, is an example of a concerted pericyclic reaction which occurs via a cyclic transition state, with the absence of formation of intermediates. It involves the reaction of a diene and a dienophile (in this case cis-butadiene and ethylene, respectively) to form a 6-membered ring system. Such reactions can be described as having either normal electron demand or inverse electron demand. Normal electron demand is experienced when the cycloaddition occurs between the HOMO of the electron-rich diene and the LUMO of the electron-deficient dienophile. Inverse electron demand is prevalent when an electron withdrawing group (EWG) on the dienophile makes it sufficiently electron-deficient that it is its LUMO that reacts with the HOMO of the dienophile which has been raised in energy by electron donating groups (EDGs). The reaction is said to be allowed if the HOMO and LUMO have the same orbital symmetries in addition to a non-zero overlap integral.[4] The Woodward-Hoffmann rules also dictate whether or not a reaction is thermally allowed or forbidden.

(Good introduction. Perhaps expand a little if you're mentioning Woodward-Hoffmann rules Tam10 (talk) 13:36, 27 January 2016 (UTC))

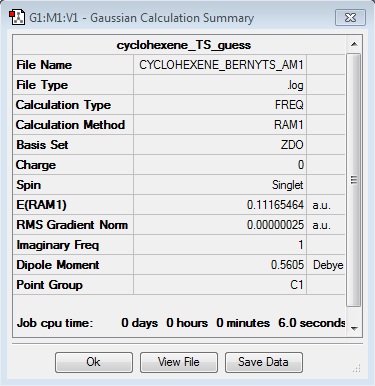

The DA cycloaddition optimisation calculations employ the AM1 semi-empirical molecular orbital method. This method is computationally cheaper in comparison to other methods because the two electron integral part of the Hamiltonian is neglected.

Geometry Optimisation of cis-butadiene

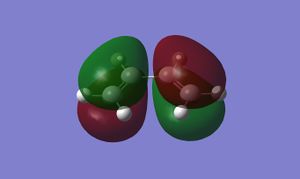

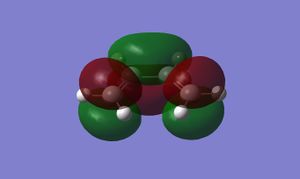

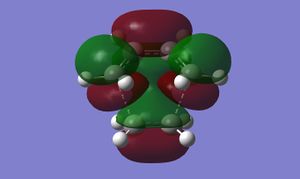

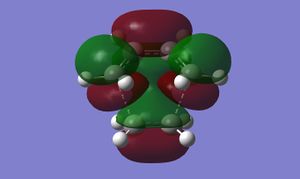

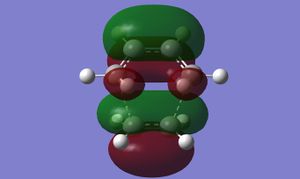

Butadiene can adopt either a trans or cis geometry, but it is only the cis isomer that can react via a DA cycloaddition. After drawing and optimising the cis-isomer in GaussView, the following HOMO and LUMO were obtained:

The HOMO of cis-butadiene is antisymmetric with respect to its symmetry plane, whilst the LUMO is symmetric.

Computation of the cis-butadiene/ethylene Diels-Alder Transition State

In order to locate the transition structure, the ethylene reactant molecule was also optimised; both the diene and dienophile could then be orientated in an envelope structure to maximise the orbital overlap. Optimisation to a Berny TS produced a cyclohexene TS of energy 0.11165464 Hartrees, and could be confirmed as being a TS by the presence of one imaginary frequency of the value -956.22 cm-1.

The formation of the two bonds in the TS is synchronous, and the partly formed sigma C-C bond lengths are 2.11926 Angstroms.

(How does the bond length compare to typical C/C bonds? Tam10 (talk) 13:36, 27 January 2016 (UTC))

(Too many significant figures for the C-C bond lengths. These calculations can't be trusted beyond 2 decimal places Tam10 (talk) 13:36, 27 January 2016 (UTC))

| Summary Data | DA Transition Structure | TS Animation | Minimum Positive Frequency Animation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| IRC Plots | IRC Animation |

|---|---|

|

|

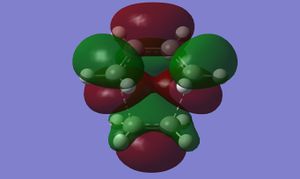

Inspection of the cyclohexene TS MOs shows us that this reaction proceeds via normal electron demand; the HOMO of cis-butadiene is higher in energy than the HOMO of ethylene. The coming together of the diene HOMO and dienophile LUMO gives rise to a symmetric LUMO in the TS. An antisymmetric TS HOMO is formed from the diene LUMO and dienophile HOMO.

(The other way around, unfortunately! Tam10 (talk) 13:36, 27 January 2016 (UTC))

| HOMO | LUMO | |

|---|---|---|

| AM1 |

|

|

| DFT |

|

|

The differences in nodal properties of the HOMOs from the two methods are quite drastic, whereas the LUMOs are virtually the same. DFT calculations use a higher basis set, including more orbitals in the calculations, which is what gives rise to the more accurate representation of the HOMO and LUMO. Using DFT, the imaginary frequency occurs at -524.99 cm-1. This is much lower than for AM1, meaning that the bonds formed in the transition state are considerably weaker.

Regioselectivity within a Diels-Alder Reaction

The product of a [4+2] cycloaddition can be either an exo or an endo adduct; which one is favoured depends upon the dienophile substituents and their ability to engage in stabilising secondary orbital interactions. In this example, the DA reaction between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride is investigated.

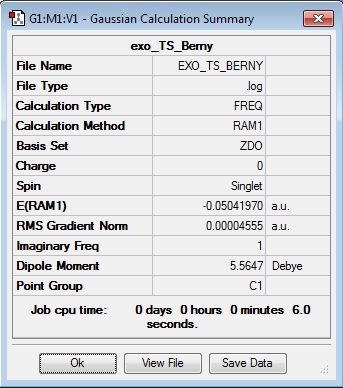

Exo Berny Transition State

Energy = -0.05041970 = -132.376932434 kJ/mol Imaginary freq. = -812.17

(This data should really be tabulated, ideally to compare with endo. Tam10 (talk) 13:36, 27 January 2016 (UTC))

(Converting absolute energies to kJ/mol isn't too meaningful. What would be better would be to take the difference between the reactant energies and the TS energy to calculate the barrier height, which can be converted to kJ/mol Tam10 (talk) 13:36, 27 January 2016 (UTC))

Transition C-C ‘bond’ lengths = 2.170 C-C through space distance between -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment = 2.280 Distance between carbons on bridge ‘opposite’ to -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- = 1.522

| TS Data Summary | DA Exo TS | TS Animation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| IRC Plots | IRC Animation |

|---|---|

|

|

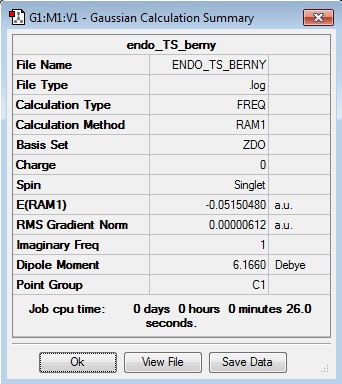

Endo Berny Transition State

energy = -0.05150480 = -135.225862701 kJ/mol Imaginary freq. = -806.33 Transition C-C ‘bond’ lengths = 2.162 C-C through space distance between -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment = 2.279 Distance between carbons on bridge ‘opposite’ to -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- = 1.397

| TS Data Summary | DA Exo TS | TS Animation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

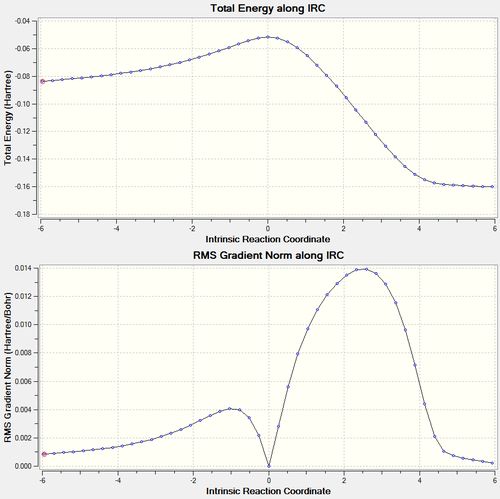

| IRC Plots | IRC Animation |

|---|---|

|

|

Optimising the exo and endo transition states using the QTS2 method produced the same results as for Berny TS.

| Adduct | Transition C-C ‘bond’ lengths/ Å | C-C through space distance in -(C=O)-O-(C=O)-/ Å | Distance between carbons on bridge ‘opposite’ to -(C=O)-O-(C=O)-/ Å |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exo | 2.170 | 2.280 | 1.522 |

| Endo | 2.162 | 2.279 | 1.397 |

(You need to put in more than just a table here to explain the steric effects. It's not too easy for someone unfamiliar to the lab to understand what you're getting at Tam10 (talk) 13:36, 27 January 2016 (UTC))

Conclusion

For the Cope rearrangement, the chair and boat transition structures were optimised and it was found that the chair TS was lower in energy as well as having a lower activation energy, thus the chair transition structure is the kinetically favoured reaction pathway.

The Diels-Alder cycloaddition was found to favour the endo transition state due to stabilising secondary orbital interactions between the diene and dienophile, in spite of the fact that the exo adduct is thermodynamically favoured.

(The secondary orbital overlap wasn't properly discussed here or in the section before. Also, did you prove that exo was the thermodynamically favoured product? Tam10 (talk) 13:38, 27 January 2016 (UTC))

The comparison of using DFT and AM1 for calculations shows that a higher level of theory (DFT) results in more accurate MOs where the nodal properties differ to those for AM1.

References

- ↑ R. B. Woodward and R. Hoffmann, "The Conservation of Orbital Symmetry", 1969, 8 (11), 781-932

- ↑ R. Ditchfield, W. J. Hehre and J. A. Pople, "Self-Consistent Molecular-Orbital Methods. IX. An Extended Gaussian-Type Basis for Molecular-Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules", J. Chem. Phys., 1971, 54 (2), 724-728

- ↑ Imperial College London, Computational Chemistry Wiki: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:phys3

- ↑ H. C. Longuet-Higgins and E. W. Abrahamson, "The Electronic Mechanism of Electrocyclic Reactions", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87 (9), 2045-2046