Rep:Mod:cr810module3

Introduction

This is the physical module of the third year computational labs - under investigation are the transition states of the Cope Rearrangement and Diels Alder Cycloaddition reactions. Gaussian will be used to calculate the potential energy surfaces and these will be used to deduce said transition states.

Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

Optimising reactants and products

Anti-Periplanar

Gauche

Comparing the energies of these two conformations, the anti conformer is the more stable, as would be expected for repulsive and steric reasons. Looking at Appendix 1, the gauche conformer is gauche2, with a relative energy of 0.62 kcal mol-1, and the anti conformer, anti1, with a relative energy of 0.04 kcal mol-1. So it can be concluded that although the anti conformer in this case is the most stable,there is still an conformation more stable - namely gauche3.

Anti2 Conformer

The has been found at the HF/3-21G level. The symmetry, as shown in Appendix 1, is Ci, and the energy is -231.69254 a.u.. The gaussian output summary is shown below:

File Name = anti2_attempt File Type = .fch Calculation Type = FOPT Calculation Method = RHF Basis Set = 3-21G Charge = 0 Spin = Singlet Total Energy = -231.69253528 a.u. RMS Gradient Norm = 0.00001469 a.u. Imaginary Freq = Dipole Moment = 0.0000 Debye |

|

This conformer was then subjected to optimisation at the higher B3LYP/6-31G(d) level, resulting in a lower energy of -234.61170 a.u.. The summary is shown below:

File Name = anti2_dft File Type = .fch Calculation Type = FOPT Calculation Method = RB3LYP Basis Set = 6-31G(D) Charge = 0 Spin = Singlet Total Energy = -234.61170283 a.u. RMS Gradient Norm = 0.00001304 a.u. Imaginary Freq = Dipole Moment = 0.0000 Debye

For direct comparison, the two optimisations are shown below side by side:

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

As can be seen above, there isn't much change in the geometry of the molecule between the different methods, despite the energy being much lower with the higher level calculations. The lower energy calculated could therefore be thought of as coming from the inclusion of more terms in the calculation, and the method being more accurate - rather than finding a more stable geometry.

Running a frequency calculation (at the same B3LYP/6-31G(d) level), the four energies are calculated:

1. Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469212 2. Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461856 3. Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.460912 4. Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500821 |

1. Potential energy at 0K, including zero-point vibrational energy; E = Eelec + ZPE. 2. Potential energy at 298.15K and 1 atm, including translational, rotational and vibrational energetic modes; E = Eelec + Evib + Erot + Etrans. |

Optimising the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition State Structures

Optimising the Chair transition state

An allyl fragment was optimised at the HF/3-21G and used to construct the chair transition structure, which was then optimised at the same level, to give the below structures (left is the transition state, right is a vibration of magnitude 818cm-1 representative of the rearrangement).

|

Another way of optimising to the transition state is through freezing the reaction co-ordinate, optimising the molecule, then unfreezing the co-ordinate and continuing the transition state optimisation again. This is a more time efficient method if the force constants would take a lot of computational time to obtain. Below are the results of this method:

|

The same geometry and imaginary vibration of 818cm-1 was obtained through this method, showing that both arrive at the same TS. (The bond making/breaking distance in this TS is 2.02Ǎ, which is short enough for there to be overlap of the Carbon VdW radii.) Therefore either method can be used to find the TS of a reaction, though the latter is better to use if the force constant calculations will be computationally costly.

Optimising the Boat transition state

The transition state is represented by the below vibration of magnitude 840cm-1, along with a labelled image for visual comparison that this is indeed the boat transition state.

|

|

The Intrinsic Reaction Co-ordinate

To identify what conformer the chair and boat transition states connect, an IRC calculation was performed upon the optimised TS structures. At first this was attempted from the respective checkpoint files, but this resulted in several errors pertaining to bad/missing data in the output files. The solution to overcome this was to simply copy and paste the geometries into blank molecule groups and run the IRC calculations from there.

| For the chair transition structure, there were 28 intermediate geometries found, using N=50. Initially it was thought to take the 28th and minimise that, however visually there was no bond between the central two atoms (C3-C4), so instead geometry 27 was optimised at the HF/3-21G level, producing the gauche2 conformer with energy -231.69167 Hartrees. |

| For the boat transition structure, N was set to 70, resulting in 29 intermediate geometries. Of these, the 29th appeared to be re-entering the boat transition state, so intermediate no. 28 was optimised at HF/3-21G, to obtain a structure not found in appendix 1. Instead, a syn-periplanar conformer of energy -231.68303 Hartrees was obtained, which is very close to the boat transition state in geometry. |

Relative Energies

To calculate the activation energies, the transition structures were optimised at the higher level of B3LYP/6-31G(d), and their respective energies compared to that of the anti2 conformer. The results of these calculations are tabulated below.

Energies of the transition states (in Hartrees)

1 hartree = 627.509 kcal/mol

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | |||

| Chair TS | -231.619322 | -231.466700 | -231.461340 | -234.556983 | -234.414929 | -234.409008 |

| Boat TS | -231.602802 | -231.450931 | -231.445302 | -234.543093 | -234.402339 | -234.396005 |

| Reactant (anti2) | -231.692535 | -231.539540 | -231.532566 | -234.611703 | -234.469212 | -234.461856 |

As can be seen above, even though the geometries are very similar - the actual calculated energies differ greatly. As such, the lower level HF/3-21G calculations should be run first to optimise the geometry to a good standard, and the higher level B3LYP/6-31G(d) applied to this pre-optimised molecule. That way the computations will be more efficient rather than starting from scratch with the high level calculation, as this would take much longer to calculate the structure and relevant energies.

Summary of activation energies (in kcal/mol)

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Expt. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | |

| ΔE (Chair) | 45.71 | 44.69 | 34.06 | 33.16 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat) | 55.60 | 54.76 | 41.96 | 41.32 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

Observing the calculated activation energies, it is clear that the higher level, DFT method, B3LYP/6-31G(d) is more accurate in it's calculated energies of the transition state, with the predictions being just within the error limits of the experimental values. Once more, this shows that for energetic calculations of this kind, it is best to pre-optimise the molecule with a lower level method, before applying something higher to obtain the most accurate values.

In conclusion, the computed values mirror those obtained by experiment, and show that the chair transition state is the lowest in energy, leading to this being the preferred structure through which the cope rearrangement takes place.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

Cis-Butadiene and Ethylene Adduct

Molecular Orbitals

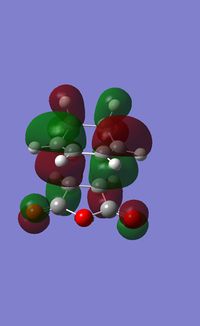

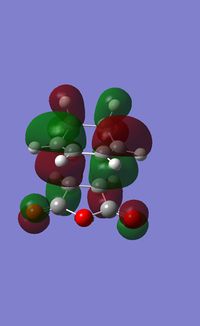

For the Diels-Alder reaction to take place, the butadiene must be in the cis isomer; this configuration was optimised in Gaussian using the AM1 semi-empirical method. The frontier orbitals, the HOMO and LUMO are shown below, alongside the optimised structure of the molecule.

The symmetry of the HOMO and LUMO is important, as these are the reacting MOs, and only orbitals of the same symmetry can interact effectively. For the HOMO, it is anti-symmetric and shall be given the assignment a. Whereas for the LUMO, the MO is symmetric about the plane, and is assigned the nomenclature of s. It should also be noted that the HOMO comprises two π-bonding orbitals (about the alkenes) with a node in the middle of the central C-C bond, whilst the LUMO consists of two π-antibonding orbitals for the alkenes, which results in a node in the middle of each, but a region of overlap over the central C-C bond.

Ethylene was also optimised, this time using the HF/3-21G method (this was chosen over the AM1 method as the molecule is so simple that there isn't much advantage time-wise for using a lower level calculation first). Again, the HOMO and LUMO are shown below, along with the structure itself.

|

|

|

In the case of Ethylene, the HOMO is symmetric, hence s, whereas the LUMO is assigned a.

Transition state of the reaction

The transition state was obtained by first orienting the ethylene molecule approximately 2.2Ǎ above the terminal carbons of the butadiene, followed by an optimisation at the HF/3-21G level. This resulted in the below geometry being obtained. The frontier orbitals were also calculated, along with an imaginary vibration of magnitude 818cm-1, and these are also shown below.

|

|

|

The vibration shows a synchronous formation of the bonds, something characteristic of a pericyclic reaction - both bonds are formed at the same time, on the same side of the molecule.

A further insight into the transition structure is the interatomic distance between the carbons. The molecule has been further optimised at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level and the bond distances measured and tabulated below, with comparisons to published bond C-C bond lengths for sp2 and sp3 [1] .

| Bond | Transition Structure | sp2 | sp3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partially formed C-C | 2.27 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

| Butadiene C=C | 1.38 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

| Butadiene C-C | 1.41 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

| Ethylene C=C | 1.39 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

The partially formed bond is still rather larger than any characteristic C-C bond, however the Van der Waals radius of Carbon is 1.7Ǎ[2], and as this interatomic distance is 2.27, this shows that there is still an overlap of the VdW surfaces and a bond is being formed. Looking at the other bonds gives an image of what is happening in the reaction: The butadiene and ethylene C=C bonds are lengthening, whilst the C-C single bond is contracting. If one compares this to the arrow pushing of this pericyclic reaction, it appears that the bonds are midway to taking on their characteristic bond lengths in the product.

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

Preparing the models

Initially ChemBio3D was used to create the two products (exo and endo), and the reactants (maleic anhydride and cyclohexa-1,3-diene), and optimise the structures quickly with the MM2 molecular mechanics method. These were then saved as MOL files and transferred to Gaussian where they were subjected to optimisation at the HF/3-21G level. This provided not only more optimal geometries, but the frontier MOs as well - all are documented in the below table.

| Cyclohexa-1,3-diene | Maleic Anhydride | Endo adduct | Exo adduct | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| .MOL file | ||||||||||||

| HOMO |

|

|

|

| ||||||||

| LUMO |

|

|

|

|

Note the degree of anti-bonding present in the LUMOs of both Diels-Alder adducts, with several nodes all over the molecule, raising the energy. Compare this to the HOMO, however, and there is a great amount of electron density about the alkene, as well as the bridging ethyl segment.

Finding the transition states

To obtain the transition structures, the HF/3-21G optimised structures of the two reactant molecules were copied into a blank molecule group in Gaussian and arranged in the appropriate orientations, as detailed below. For both structures, the frozen co-ordinate method was applied. This involved first 'freezing' the C=C of the anhydride (using the redudant co-ordinate editor and the freeze co-ordinate function) above the two alkenes of the diene at approximately 2.2Ǎ, and then optimising the rest of the molecule under HF/3-21G. Afterwards, if successful, the redundant co-ordinates of the partial bonds were set to derivative and an opt+freq job run under HF/3-21G, with the write connectivity option deselected as the calculation fails otherwise. It should be noted that the keyword opt=noeigen was also employed, to prevent any crashing of the calculation - as per the tutorial.

Exo Adduct

The exo Adduct was obtained at the HF/3-21G level with an energy of -605.60359017 a.u.. Below is a mol file of the TS, a vibration of magnitude 648cm-1 representing the forming/breaking of the new c-c bonds, and the frontier MOs.

|

|

|

| Bond | Transition Structure | sp2 | sp3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partially formed C-C | 2.26 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

| Diene C=C | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

| Diene C-C | 1.39 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

| Dienophile C=C | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

Endo Adduct

The Endo TS was obtained at the HF/3-21G level with an energy of -605.6103681 a.u., and an imaginary vibration of 644cm-1 in magnitude to represent the bond forming/breaking of the reaction. Again, the relevant images are shown below.

|

|

|

The frontier orbitals of this TS are also antisymmetric with respect to the bisecting plane of the structure, so once again the HOMO of the diene is interacting with the LUMO of the diene. However, this time the maleic anhydride is oriented differently, with the C=O held over the C=C of the diene. This allows for secondary orbital interactions where the anti-bonding orbitals of the C=O interact with the bonding π-orbitals of the alkene groups, leading to greater stabilisation of this TS compared to that for the exo adduct. A comparison of the C-C and C=C bonding distances in this transition structure may also give an insight into the reaction, tabulated below.

| Bond | Transition Structure | sp2 | sp3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partially formed C-C | 2.23 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

| Diene C=C | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

| Diene C-C | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

| Dienophile C=C | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.54 |

Once more, the double bonds are lengthening whereas the single bonds are shortening as the π-electron density increases. The partially formed C-C bonds are shorter than those in the Exo TS - highlighting that this TS is closer to forming the bonds and is therefore more stable, as seen in the lower energy calculated.

Comparison of Transition States

By directly comparing the total energies of the TS at the HF/3-21G level, the Endo TS is more stable by 4.25 kcal mol-1, and therefore the activation energy of this reaction path is much lower, which would mean that the rate of reaction towards the Endo product is much faster than that of the Exo adduct. In fact, the Exo adduct, despite being the thermodynamically more stable product [3], is rarely formed at all. This is known as the Diels-Alder Endo rule, and shows that this reaction is under kinetic, rather than thermodynamic control.

| Exo | Endo | Relative stability of Endo TS |

|---|---|---|

| - 605.60359017 a.u | - 605.6103681 a.u. | - 0.00677793 a.u. (= - 4.25 kcal mol-1) |

By inspecting the non-bonding distances of the structures, a picture of the balance of attractive and repulsive interactions contributing to the geometry can be formed. In the case of the Exo TS, the distance between the Carbons of the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment of maleic anyhydride and the -CH2-CH2- fragment directly underneath is 2.92Ǎ, whilst the C-C distance where the new bonds are forming is 2.26Ǎ. For the endo structure, it is the distance from the maleic anhydride fragment to the -CH=CH- groups that is measured as 2.85Ǎ, with the partially formed bonds being 2.23Ǎ.

With these distances calculated, although all distances are short enough for overlap of VdW radii, only the endo structure has both attractive interactions, with bonds being formed and favourable π-interactions that stabilise the transition state. The exo TS does have partially formed C-C bonds, but the energy is raised by the steric clashing with the -CH2-CH2- fragment. Therefore, the more stable TS - hence favoured reaction pathway - is the endo TS.

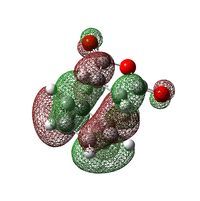

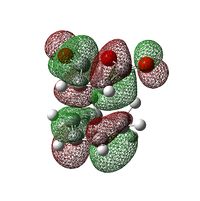

The secondary orbital overlap effect

To investigate the secondary orbital overlap, the HOMOs of both the exo and endo TS are shown below. If both jmol surfaces are oriented with the maleic anhydride is facing the same direction, it can be seen that although there is a large amount of electron density above the C=O bonds, there is a node as the phases of the orbitals are opposite. Therefore there is no apparent overlap. This is the opposite of what the secondary orbital overlap argument states. So from this evidence, it seems that this effect does not contribute to the stabilisation of the endo TS relative to the exo structure. Instead, there are other interactions such as electrostatic effects, hydrogen bonding, etc. that have not been taken into account in these calculations[4] and would be good for further investigation to determine the cause of this stability.

| Exo | Endo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

References

- ↑ http://web.pdx.edu/~wamserc/CH331F96/notes/Ch1notes.htm [Accessed 31/10/12]

- ↑ http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/products/csd/radii/table.php4 [Accessed 30/10/12]

- ↑ Clayden, Greeves, Warren and Wothers, Organic Chemistry, 8th Ed., Oxford University Press

- ↑ Garcia JI, Mayoral JA, Salvatella L; Acc. Chem. Res., 2000, 33, 658-664, Available from: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ar0000152 [Accessed 02/11/12]