Rep:Mod:cr810module1

Introduction

This is the organic module for the third year computational chemistry lab

Part 1

Hydrogenation of the Cyclopentadiene Dimer

| Using the MM2 forcefield in ChemBio3D, molecules 1-4 were minimised in their energy, and the various components towards this total recorded (see table). |  |

| Molecule | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole-Dipole (H-bond) | Total Energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.2857 | 20.5811 | -0.8382 | 7.6541 | -1.4162 | 4.2324 | 0.3775 | 31.8765 |

| 2 | 1.2516 | 20.847 | -0.8357 | 9.5108 | -1.5433 | 4.3196 | 0.4476 | 33.9975 |

| 3 | 1.2777 | 19.8661 | -0.8349 | 10.8068 | -1.2256 | 5.6329 | 0.1621 | 35.685 |

| 4 | 1.0966 | 14.5251 | -0.5491 | 12.4978 | -1.0707 | 4.5119 | 0.1406 | 31.152 |

|

|

For the first pair of molecules, 1 and 2, the more stable of the two is molecule 1 - the exo product. If the reaction was under thermodynamic control, which is the case if the reaction was reversible, then this would be the favoured isomer formed. However, it is not observed at all. Instead, molecule 2, the endo product, is the sole isomer present. This shows that the stability of the final product has no bearing on which isomer is formed, and as such this reaction is deemed to be under kinetic control. This preference for the endo adduct is known as the Diels-Alder endo rule, and is due to a bonding interaction of the two pi-systems of the diene and dienophile, if the two molecules are orientated correctly in the transition state. This stabilises the transition state of the endo product relative to the exo form, allowing a much faster rate of reaction.[1] |

Comparing the energetic values of molecules 3 and 4, it can be seen that molecule 4 is much less strained (14.53 kcal mol -1 compared to 19.87 kcal mol-1) and as such is the more thermodynamically stable product. The main source of strain for both molecules is the alkene double bond, and this can be used to explain why molecule 4 would be the preferred product of hydrogenation. The position of the alkene in molecule 3, coupled with the higher calculated strain shows that this alkene is the more strained of the two, and as such is more reactive. Therefore it is much easier to hydrogenate than the alkene in the larger ring, resulting in the more thermodynamically stable molecule 4.

Atropisomerism of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

The MM2 force field was also used to determine the more stable of the two atropisomers, molecules 9 and 10. Once more, the calculated energies are displayed in a table (below). To understand the effect of hyperstable alkenes, the corresponding hydrogenated molecules have also been subjected to the calculation, the relative stabilities of the two isomers can be seen by the energy of hydrogenation - i.e. the energy difference between the alkene and its appropriate alkane derivative. Care was taken after the initial MM2 minimisation to investigate the structure and it was found that the 6-membered ring was in the unstable, twist-boat conformation. Manual rearrangement of the atoms of this ring, followed by a further minimisation under MM2, yielded the chair conformation and the most stable overall conformation for the molecules. It should be noted that using the other available force field, MMFF94, does result in very similar conformations, but the energetic value differs by approximately 20 kcal mol-1, and there is no breakdown of the specific contributions. As such, it isn't as useful to help rationalise relative stabilities and reactivities of the isomers.

| Molecule | Stretch | Bend | Stretch-bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole-Dipole (H-bond) | Total Energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 2.5489 | 11.3706 | 0.3202 | 17.3658 | -2.2578 | 12.7421 | -1.6995 | 40.3902 |

| 9 alkane | 2.9705 | 17.6643 | 0.6798 | 23.0739 | -1.4427 | 16.1278 | -1.7740 | 57.2995 |

| 10 | 2.6196 | 11.3402 | 0.3431 | 19.6715 | -2.1623 | 12.8731 | -2.0024 | 42.6829 |

| 10 alkane | 2.7112 | 18.8443 | 0.5858 | 20.2296 | -2.1900 | 16.1945 | -1.7452 | 54.6302 |

As can be seen in the above table, the isomer 9, with the upward pointing carbonyl group, is the more stable of the two by 2.29 kcal mol-1.

Hyperstability

Comparison of the strain (bend term) of the alkenes and their alkane derivatives highlights something very unusual - both alkenes are less strained than the parent hydrocarbon, by a surprisingly large 6.29 and 7.50 kcal mol-1 respectively. In fact, the olefin should actually be more strained than its alkane counterpart. By definition, a hyperstable alkene contains less strain than its parent hydrocarbon, and has a negative OS (Olefinic Strain) value - in this case, OS = -6.29 and -7.50 kcal mol-1 [2]. These special alkenes are very unreactive. However, this cannot only be explained by the thermodynamic stability of the molecule. Another explanation could be afforded by thinking about the MOs involved in chemical reactivity - the HOMO and LUMO. The majority of the strain that could exist in an alkene would be twisting of the double bond, which in turn would disrupt the overlap of pi-orbitals. This would lower the LUMO in energy whilst simultaneously raising that of the HOMO - effectively contracting the HOMO-LUMO gap, and making the alkene more reactive. Therefore it could be concluded that the lower the OS, then the better the orbital overlap and hence larger the HOMO-LUMO gap. So, in the case of these hyperstable alkenes, there must be very little strain about the double bond, resulting in an energy gap that would be substantially large enough to cause abnormal unreactivity.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene to a Diene

| Molecule 12 was first minimised using the MM2 forcefield, and then subjected to MOPAC minimisation (using the RM1 method). The former uses molecular mechanics whereas the latter also includes stereoelectronic effects. A direct comparison (see JMOL) can be made by overlaying the two molecules. This was achieved by choosing several corresponding pairs of atoms between the two optimised geometries and minimising the distance between the consituents. In this case, four atoms were chosen: the chlorine, the carbon of the methyl group, the carbon that is bonded inbetween these two, and one of the bridgehead carbons. The chlorine and the methyl group were chosen as they were the two atoms most likely to have an effect on the conformation of the rest of the molecule, and the other two carbons because they were in the middle of the molecule. By choosing to minimise the distance between these pairs, the conformational difference of the two six-membered rings between the geometries can better be seen. |

As shown in the JMOL file, the ring underneath the methyl group is barely affected once electronic effects are considered, however, when comparing the side under the chlorine - a clear discrepancy between the optimisation performed under MM2 and that under MOPAC can be seen. Therefore it can safely be said that whilst molecular mechanics alone can give a rough estimate of a molecule's structure, once atoms other than carbon and hydrogen begin to appear, more complex effects need to be taken into account.

Using Density Functional Theory (DFT) to investigate the reactivity

By implementing the B3LYP method, along with the 6-31G basis set, through Gaussian, the geometry was first optimised (using the earlier MOPAC optimisation as a starting point), and then the MO's and vibrational modes of the molecule computed. The important MO's to look at are those surrounding the HOMO-LUMO pair - the frontier orbitals, and these are displayed below.

|

|

|

|

| The HOMO shows a lot of electron density about the alkene underneath the chlorine, whereas the HOMO-1 orbital shows density over the other double bond. As such, it can be predicted that the former is the more reactive as it is most dominant in the MO higher in energy. However, the MOs can also help explain the lower energy of the other alkene: The LUMO shows the σ*C-Cl bond, which is unoccupied. If the LUMO and HOMO-1 orbitals are overlaid (as shown to the right), it can be seen that there is an overlap of this empty orbital with the filled π orbital of the alkene on the "methyl side". This allows for some donation of electron density into the σ*, which has two effects: the lowering of the bond order, making the double bond weaker, and also, somewhat counterintuitively, the lowering of the reactivity too; alkenes usually react via electrophilic substitution, so a decrease in the electron density means a decrease in the reactivity. |

|

Using IR Spectroscopy to differentiate between the alkenes

Looking at the calculated vibrational modes confirms a slightly weaker double bond for the alkene underneath the methyl group - there are two C=C stretches, one at 1752.88cm-1 and the other at a slightly higher 1765.51cm-1. Their respective animations (left to right as calculated via Gaussian) are shown below, along with the calculated IR spectrum.

|

|

|

| A further confirmation of this reactivity can be drawn from the electrostatic potential of the molecule, calculated in Gaussian (see right). It can clearly be seen that there is significantly more electron density over the alkene underneath the chlorine atom, increasing it's reactivity compared to the other double bond. |

|

Monosaccharide chemistry and the mechanism of glycosidation

Both MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 have been used to obtain the optimal geometries of the 4 possible conformations and configurations (2 conformations for each of the axial and equatorial configurations of the ester) for the oxonium cation intermediate A. Their mol files and relative energies are shown in the table below. n.b. MM2 energies are steric energy, whilst MOPAC energies are heats of formation.

| Method | Axial | Equatorial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Above | Below | Above | Below | |

| MM2 | 34.21 kcal mol-1 |

31.85 kcal mol-1 |

35.54 kcal mol-1 |

31.77 kcal mol-1 |

| MOPAC/PM6 | -91.64 kcal mol-1 |

-69.23 kcal mol-1 |

-86.49 kcal mol-1 |

-83.66 kcal mol-1 |

| It can be seen that for MM2, the favoured conformations are both when the carbonyl is below the oxonium carbon, with not much difference between the axial or equatorial configurations. However, with the inclusion of the electronic effects in the calculations used with MOPAC/PM6, it appears to be the conformation with the carbonyl above that is most favoured, especially in the case of the axial configuration. If the relevant jMol file is consulted (see right), it can be seen that the carbonyl oxygen is held in almost a perfect example of the Burgi-Dunitz trajectory [3]. This would provide optimal overlap of the lone pair on the oxygen with the π* C=O of the oxyonium ion, allowing stabilisation of the cation via electron donation. This effect is not effectively taken into account by the molecular mechanics approach. |

The same procedure was applied to intermediate B, again with the results outlined in the table below.

| Method | Axial | Equatorial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Above | Below | Above | Below | |

| MM2 | 36.06 kcal mol-1 |

34.57 kcal mol-1 |

43.36 kcal mol-1 |

38.69 kcal mol-1 |

| MOPAC/PM6 | -91.64 kcal mol-1 |

-66.95 kcal mol-1 |

- 66.84 kcal mol-1 |

-91.66 kcal mol-1 |

Immediately noticeable in the results is the striking similarity of the energies calculated via MOPAC/PM6 with those for intermediate A. It seems that even without the bonds being formally defined, the semi-empirical method fully took into account the ability of the carbonyl to stabilise the oxonium ion via electronic orbital interactions. The results from MM2 calculations seem contradictory and confusing when compared to those from MOPAC, highlighting the limitations of a purely molecular mechanics approach when modelling a molecule that is heavily stabilised via electronic effects. If a MOPAC minimisation was followed by MM2, the most stable MM2 geometry would likely be reached. However, this would not have been acquired by MM2 alone.

Part 2

DSPACE:http://hdl.handle.net/10042/20874

| Intermediate 18 from the featured[4] synthesis of Taxol was drawn in ChemBio3D, before being subjected to the following minimisations: MM2 --> MOPAC/PM6 -->DFTB3LYP/6-31G(d,p). Once this optimised structure was obtained, the mpw1pw91 method (with the same basis set of 6-31G(d,p)) was used to obtain the NMR spectra. The jmol to the right can be used to identify the number of the atom in the assignment: right click and go to style->labels->label with atom number. (There are also several options for changing the colour, position etc of the labels). |

| GIAO | Literature | |

|---|---|---|

| δ/ppm | Gaussian Assignment | δ/ppm |

| 23.63 | 17 - Methyl on bridge pointing into molecule | 19.83 |

| 24.47 | 15 - Methyl substituent of 6-membered ring | 21.39 |

| 24.77 | 12 - CH2 in original 5-membered ring | 22.21 |

| 24.78 | 9 - CH2 in 6-membered ring | 25.35 |

| 25.68 | 18 - Methyl on bridge pointing out of molecule | 25.56 |

| 28.74 | 13 - CH2 next to bridgehead alkene, original 5-membered ring | 30.00 |

| 31.12 | 10 - CH2 in 6-membered ring, closest to carbonyl oxygen | 30.84 |

| 37.40 | 5 - CH2 adjacent to carbonyl in larger ring | 35.47 |

| 39.07 | 1 - CH2 adjacent to alkene, between alkene and start of 6-membered ring | 36.78 |

| 41.49 | 22 - CH2 within ring between the two sulphur atoms | 38.73 |

| 42.97 | 8 - CH2 adjacent to the C-S linkage in the 6-membered ring | 40.82 |

| 44.55 | 23 - CH2 within the ring between the two sulphur atoms | 43.28 |

| 50.91 | 16 - Quaternary carbon within the bridge, between the two methyl groups | 45.53 |

| 53.53 | 11 - CH Bridgehead opposite alkene | 50.94 |

| 58.91 | 3 - Quaternary carbon attached to the methyl substituent in the larger ring | 51.30 |

| 64.25 | 2 - Tertiary carbon attached to 6-membered ring, adjacent to carbon 3 | 60.53 |

| 90.67 | 7 - Quaternary carbon in the 6-membered ring, attached to both sulphurs | 74.61 |

| 124.08 | 6 - CH as part of the alkene | 120.90 |

| 145.18 | 14 - CR2 as other carbon in alkene | 148.72 |

| 212.75 | 4 - C within carbonyl | 211.49 |

It should be noted that the exact conditions (solvent, method, basis set etc.) were unavailable in Gaussian at the time, as such the correct basis set and method were used, but no solvent selected. However, for the most part, the computed shifts are within the rule of thumb limit of ±5ppm. The largest error appears to be Carbon #7, the carbon for which both sulphurs are bonded to. Looking at the jmol file, and the output file in Gaussian, one of the Sulphurs appears to not be bonded. Maybe an error occurred during one of the minimisation processes - however, due to time constraints, a repeat job cannot be processed.

Aside from the above error, it seems reasonable to say that the assignments given by Gaussian can be applied to the literature molecule.

Due to further time constraints, it has not been possible to assign the 1H NMR shifts.

Literature Molecule: 2-(1,1-Dimethyl-allyl)-malonic acid dimethylester

DSPACE: Isomer A - http://hdl.handle.net/10042/20855 Isomer B - http://hdl.handle.net/10042/20851 (both for NMR)

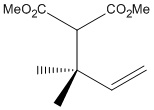

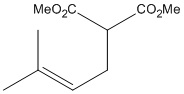

| The above molecule has been synthesised [5] and reported as one of two isomers, in the ratio of 98:2 A:B - a highly regiospecific reaction. To the right are the molecules, dubbed A and B from now on for ease of reference (clicking the buttons loads the jmol model, optimised through DFTB3LYP/6-31G(d,p)). |  |

|

To check the accuracy of the literature assignments[6] for the spectroscopic data, computational methods have been used to calculate the 1H and 13C NMR peaks, along with the IR vibrations. Before these calculations were made, the geometry of both isomers was optimised in the same way as the earlier Taxol intermediate (with the final optimisation being the better DFT method for NMR calculations): MM2 --> MOPAC/PM6 --> DFTB3LYP/6-31G(d,p) -->mpw1pw91/6-31G(d,p)

1H NMR

The images of the isomers (open in new tab) show the labels used for the assignments of atoms

|

|

| GIAO - A | GIAO - B | Literature[6] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ /ppm | Multiplicity | Rel. Integral. | Gaussian Assignment | δ /ppm | Multiplicity | Rel. Integral. | Gaussian Assignment | δ /ppm | Multiplicity | Rel. Integral. |

| 0.86 | s | 1H | 16 - Methyl | 1.46 | s | 1H | 18 - Alkene Methyl | 1.19 | s | 6H |

| 0.93 | s | 1H | 17 - Methyl | 1.47 | s | 1H | 19 - Alkene Methyl | 3.34 | s | 1H |

| 1.26 | s | 1H | 19 - Methyl | 1.65 | s | 1H | 16 - Alkene Methyl | 3.66 | s | 6H |

| 1.27 | s | 1H | 20 - Methyl | 1.78 | s | 1H | 15 - Alkene Methyl | 4.98 | d, J= 10.8 Hz | 1H |

| 2.23 | s | 1H | 21 - Methyl | 1.80 | s | 1H | 17 - Alkene Methyl | 5.00 | d, J= 17.2 Hz | 1H |

| 2.27 | s | 1H | 18 - Methyl | 2.09 | s | 1H | 20 - Alkene Methyl | 6.01 | dd, J= 17.2, 10.8 Hz | 1H |

| 3.51 | s | 1H | 15 - CH | 2.57 | s | 1H | 22 - CH2 | |||

| 3.71 | s | 1H | 25 - Ester Methyl | 2.76 | s | 1H | 23 - CH2 | |||

| 3.80 | s | 1H | 29 - Ester Methyl | 3.48 | s | 1H | 24 - CH | |||

| 3.91 | s | 1H | 26 - Ester Methyl | 3.78 | s | 1H | 29 - Ester Methyl | |||

| 3.92 | s | 1H | 28 - Ester Methyl | 3.89 | s | 1H | 26 - Ester Methyl | |||

| 3.97 | s | 1H | 30 - Ester Methyl | 4.00 | s | 1H | 30 - Ester Methyl | |||

| 4.19 | s | 1H | 27 - Ester methyl | 4.02 | s | 1H | 25 - Ester Methyl | |||

| 5.31 | s | 1H | 23 - Alkene CH2 | 4.07 | s | 1H | 27 - Ester Methyl | |||

| 5.38 | s | 1H | 24 - Alkene CH2 | 4.40 | s | 1H | 28 - Ester Methyl | |||

| 6.38 | s | 1H | 22 - Alkene CH | 5.44 | s | 1H | 21 - Alkene CH | |||

Gaussian has given all the NMR peaks as singlets, and there are a lot more environments than those reported in the literature[6]. However, there is an easy explanation for this: in the literature, the individual hydrogens on the methyls etc. are rotating about the bond so fast that we observe an average peak, instead of the individual absorptions. As such, it is now possible to confirm the validity of the claim to have produced isomer A:

- The singlet at 1.19ppm with an integral of 6H can be one of three things: 6 x CH, 3 x CH2, or 2 x CH3. The only possibility with this molecule is two identical methyl groups, either the alkene methyls of B or the two methyls from A. Looking at the chemical shift, it is too low for the groups to be next to an alkene. Therefore this is attributed to isomer A.

- The singlet at 3.34ppm for 1H is equally likely to be from either isomer.

- The singlet at 3.66ppm for 6H is once more due to two identical methyl groups, this time those in the ester groups. However, there is no real way to distinguish between the two isomers.

- The doublets of 1H each at 4.98ppm and 5.00ppm can only be assigned to the two protons of the CH2 of the alkene. They themselves are in very similar chemical environments, the rigidity of the double bond preventing them from being observed as a singlet. The calculated shifts for isomer B are too low, whereas those for A are much closer - therefore more evidence that A has indeed been synthesised.

- The doublet of doublets can only be the CH proton of the alkene, it is coupled to the two protons on the other side of the alkene, each with slightly different coupling constants, leading to observed splitting pattern. The chemical shift of this peak tends slightly towards that calculated for A, although alone it wouldn't be enough evidence to support a definitive conclusion.

13C NMR

A strong case for isomer A's presence has been built, but more confirmation would be welcome. Thankfully the 13C NMR spectrum for A has also been computed. If there is enough correlation between the two, then it is undoubtedly confirmed that A has been reported correctly. note: the earlier labelled images still apply to help identify the assignments visually

| GIAO - A | GIAO - B | Literature[6] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ /ppm | Gaussian Assignment | δ /ppm | Gaussian Assignment | δ /ppm |

| 19.67 | 4 - Methyl | 18.75 | 3 - Alkene Methyl | 25.2 |

| 28.93 | 3 - Methyl | 27.22 | 1 - Alkene Methyl | 39.0 |

| 44.82 | 2 - CR4 | 31.60 | 5 - CR2H2 | 52.1 |

| 53.66 | 14 - Ester Methyl | 55.96 | 11 - Ester Methyl | 60.7 |

| 56.50 | 10 - Ester Methyl | 56.10 | 6 - CHR3 | 112.5 |

| 61.95 | 1 - CHR3 | 57.04 | 14 - Ester Methyl | 144.7 |

| 110.07 | 6 - Alkene (terminal carbon; C=CH2) | 118.70 | 4 - Alkene (internal carbon; C=CHR) | 168.4 |

| 144.07 | 5 - Alkene (internal carbon; C=CHR) | 135.78 | 2 - Alkene (terminal carbon; C=CR2) | |

| 164.12 | 7 - Ester C=O | 163.96 | 7 - Ester C=O | |

| 166.27 | 11 - Ester C=O | 166.95 | 8 - Ester C=O | |

It can be seen that once more, there are more peaks from Gaussian than those reported, and the explanation still holds - rotation about the bonds results in an averaging of the environments.

- The environment at 25.2ppm corresponds to the two methyl groups - but it's difficult to differentiate between A or B

- The peak at 39.0ppm is easier to assign, and this can be assigned to the quaternary carbon present only in isomer A.

- The 52.1ppm peak can be assigned to the two ester methyls, but once again there's no clear difference between either isomer.

- The peak at 60.7ppm can be attributed to the tertiary carbon, and it can be argued to be very close to that predicted for A.

- The 112.5ppm absorption is most likely that of the terminal carbon in the alkene of A - the two hydrogens do not deshield as much as the methyl present in B.

- The 114.7ppm environment is remarkably close to that calculated for the internal carbon of the alkene in isomer A.

- Finally, the 168.4ppm peak can be assigned to the ester carbonyl carbon, although as this is present in both isomers in the same environment, this doesn't bias the conclusion either way.

IR Vibrational Modes

DSPACE: Isomer A - http://hdl.handle.net/10042/20899 Isomer B - http://hdl.handle.net/10042/20900 (for IR)

| A | B | Literature[6] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band / cm-1 | Gaussian Assignment | Band / cm-1 | Gaussian Assignment | Band / cm-1 |

| 1158.17 | CH rock (methyl) | 1138.38, 1151.51, 1166.17 | Alkene Methyl rock (weak), CH2 rock (strong), Ester Methyl rock | 1142 |

| 1264.51, 1266.37 | CH bend | 1238.62, 1251.18, 1272.65 | C-H wave (1272.65 v. strong) | 1245 |

| 1314.7 | C-H wag | 1328.88 | C-H wave (strong) | 1327 |

| 1407.37,1426.06,1463.69,1479.28 | CH3 Bending (1463 is CH2 bending) | 1436.42 | Alkene CH3 bending (extremely weak!) | 1435 |

| 1724.14 | C=C stretch (v. weak) | 1749.95 | C=C stretch (v. weak) | 1736 |

| 1808.04, 1834.56 | C=O stretches | 1810.29, 1831.10 | C=O stretches (very strong, medium-strong) | |

| 3047.36-3067.31 | C-H methyl stretch | 3023.24-3067.17 | C-H methyl stretch | 2955 |

Unlike with the NMR absorptions, there doesn't seem to be a way of clearly determining between the two isomers using IR as the same functional groups are present in both isomers. The literature only mentions characteristic absorptions but there was no attempt to assign them, so that shall be done using the computed results as a guide:

- 1142cm-1 seems to be an absorption that the authors decided was the strongest within that region, as there would be several - as evidenced by the two computed spectra. This is an area known as the fingerprint region, and contains several CH rocking, waving, and wagging modes. As such, this is a difficult band to assign without a visual aid such as the animations provided by Gaussian. Due to this, it shall simply be assigned CH rocking as the computed absorptions in this region exhibited that characteristic motion.

- 1245cm-1 is similar to the previous peak, this is again in the fingerprint region and is probably one of many such absorptions observed. It shall be assigned C-H waving.

- 1327cm-1 is surprisingly close to the strong band seen for isomer B for C-H waving, and is assigned the same mode of vibration.

- 1435cm-1 is also very close to a peak observed for isomer B, for Alkene CH3 bending, although in the computed spectra this was exceptionally weak. No strength of signal was mention in the literature but this will be assigned the same bending mode.

- 1736cm-1 is in the region expected for both C=C and C=O stretches. However both computed spectra have a C=C stretch in this region, and so this will be given that assignment.

- 2955cm-1 is lower than the computed absorptions of the same region, but will still be given the C-H stretching mode.

It seems surprising that for a molecule containing two C=O bonds, the literature[6] fails to report any absorptions for them. Possibly the authors thought them not very indicative of what isomer was present and chose to omit them. However, the remaining peaks aren't very helpful in identifying the structure. It appears that, in this case, IR spectroscopy is more helpful in confirming the presence of functional groups, but is no help in distinguishing between the isomers.

Conclusion

Despite the the computed IR spectra not being much help in identifying the isomer reported. Both NMR spectra showed strong evidence for the presence of isomer A, which was the assignment originally given in the literature.(In fact this was such a regiospecific reaction that the ratio of A:B was 98:2![5]) Through comparison with the computational results, the previously unassigned NMR and IR values in the literature were given to their most likely environments and vibrational modes respectively. This exercise shows the importance of spectroscopic and computational techniques in analysing, assigning, and checking that the correct isomer has been produced, especially in situations were several isomeric products may occur.

References

- ↑ Clayden, Greeves, Warren and Wothers, Organic Chemistry, 8th Ed., Oxford University Press

- ↑ Wilhelm F. Maier, Paul Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891. DOI: 10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ Bürgi, H. B.; Dunitz, J. D.; Shefter, E., "Geometrical Reaction Coordinates. II. Nucleophilic Addition to a Carbonyl Group". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 5065-5067

- ↑ L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.200503274/pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 http://www.wiley-vch.de/contents/jc_2002/2006/z503274_s.pdf