Rep:Mod:cn816

NH3 Molecule

Summary of optimisation results

| Molecule | NH3 |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final energy E(RB3LYP) | -56.55776873 |

| RMS gradient | 0.00000485 |

| Point group | C3V |

| N-H bond length | 1.01798 Å |

| H-N-H bond angle | 105.741° |

Item Table

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000004 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000072 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000035 0.001200 YES

The optimisation file is linked to here

3D visualisation of NH3

Optimized NH molecule |

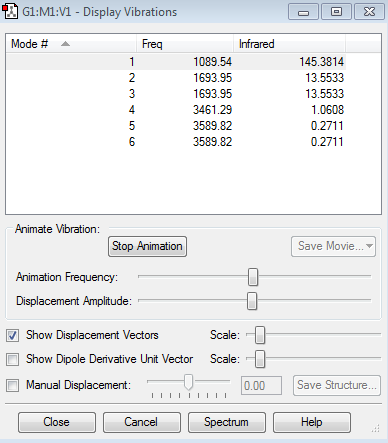

Vibration modes of NH3 Molecule

Expected number of modes: 6

Modes which are degenerate: (2,3), (5,6)

Bending vibration modes: 1,2,3

Bond stretch vibration modes: 4,5,6

The mode that is highly symmetric:4

"umbrella" mode: 1

Number of bands expected to see in an experimental spectrum of gaseous ammonia: 3

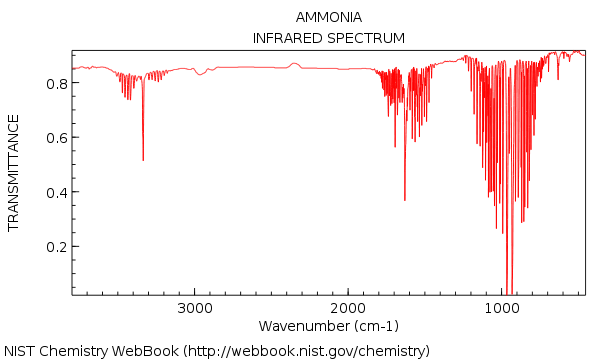

IR spectrum of NH3 Molecule

This is the gas phase IR spectrum for NH3.[1]

As it can be seen, there are three peaks corresponding to the N-H bends and stretches at around 1000, 1700 and 3400 cm-1. This corresponds to the stretching frequencies we have attained in our calculations. The last peak at 3600 is too small an intensity to be observed on the IR spectra. The IR spectra of NH3 also shows rotational coupling, resulting in the large band of tiny peaks within each peak

Atomic charges

Charge on N = -1.125

Charge on H = 0.375

It is expected that N would have a negative atomic charge while H has a positive atomic charge as N is more electronegative than H and will draw electron density to itself, resulting in a high electron density at N and low electron density on H.

N2 Molecule

Summary of optimisation results

| Molecule | N2 |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final energy E(RB3LYP) | -109.52412868 |

| RMS gradient | 0.00000060 |

| Point group | D∞h |

| N-N bond length | 1.10550 Å |

| N-N bond angle | 180° |

The optimisation file is linked to here

Item Table

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000001 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000000 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000000 0.001200 YES

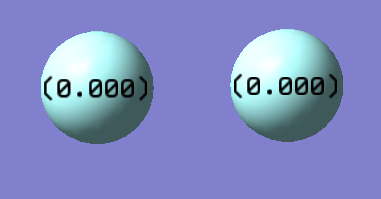

3D visualisation of N2

Optimized N molecule |

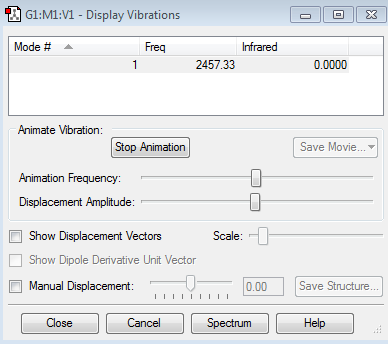

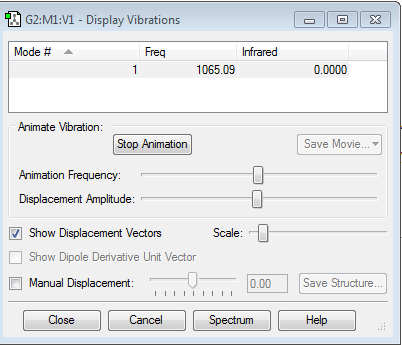

Vibration modes of N2 Molecule

N2 is IR inactive as it is a homodinuclear molecule with no dipole moment. (Hence an IR intensity of 0)

H2 Molecule

Summary of optimisation results

| Molecule | H2 |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final energy E(RB3LYP) | -1.17853936 |

| RMS gradient | 0.00000017 |

| Point group | D∞h |

| H-H bond length | 0.74279 Å |

| H-H bond angle | 180° |

Item Table

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000000 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.001200 YES

The optimisation file is linked to here

3D visualisation of H2

Optimized H molecule |

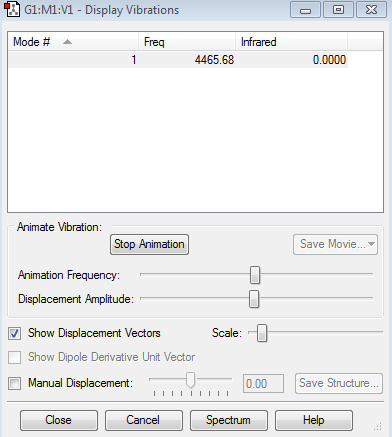

Vibration modes of H2 Molecule

H2 is IR inactive as it is a homodinuclear molecule with no dipole moment. (Hence an IR intensity of 0)

Calculating the energy for the Haber process

E(NH3)= -56.55776873

2*E(NH3)= -113.11553746

E(N2)= -109.52412868

E(H2)=-1.17853936

3*E(H2)=-3.53561808

ΔE=2*E(NH3)-[E(N2)+3*E(H2)]= (-0.0557907 x 2625.5) kjmol-1 = -146.47848285 kjmol-1 = -146.48 kjmol-1 (2 d.p.)

As the reaction is exothermic as seen from the negative overall energy change, ammonia product is more stable.

Comparing it to literature [2] values of the same process of -92kjmol-1 , we can see that the calculated enthalpy change is much more exothermic than in experiments. This is because these density functional theory calculations assume that our molecules are at 0K and are very poor in taking the long range interactions between molecules into account. In real life, experiments are usually conducted at 298k and at this temperature, molecules have intermolecular forces of attraction that need to be overcome as well. DFT calculations deal with isolated molecules and fail to take this into account. Hence the experimental enthalpy change will be less exothermic than the theoretical value at 0k as these interactions need to be overcome.

Chosen molecule: F2 Molecule

Summary of optimisation results

| Molecule | F2 |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final energy E(RB3LYP) | -199.49825218 |

| RMS gradient | 0.00007365 |

| Point group | D∞h |

| F-F bond length | 1.40281 Å |

| F-F bond angle | 180° |

Item Table

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000128 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000128 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000156 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000221 0.001200 YES

The optimisation file is linked to here

3D visualisation of F2

Optimized F molecule |

Vibration modes of F2 Molecule

F2 is not IR active as it is a homodinuclear molecule. (Hence the IR intensity is 0)

Distribution of charges of F2 Molecule

Molecular orbital diagrams

This molecular orbital is attained from the mixing of the 1s orbitals of F. Molecular orbital is symmetric about the intramolecular axis and hence it is gerade. Because of the extremely high electronegativity of the F atoms, the 1s orbitals are very contracted and pulled very close to the nuclei such that we do not see much of a molecular orbital in this diagram.

This molecule is attained form the mixing of the 2s orbitals of F. Molecular orbital is symmetric about the intramolecular axis and hence it is also gerade. Comparing it to the figure above, the molecular orbital is bigger as it is formed form the mixing of bigger and more diffuse 2s orbitals. Bond strength is also weaker (as seen from the higher energy of the molecular orbital formed) as there is less localised electron density between the two bonding F atoms.

This is a sigma bond formed via the head-on overlap of a 2p orbital from each F atom. There are two nodal planes located on the nuclei of each atom.

This is a pi bond formed via the sideways overlap of 2p orbitals of F. Molecular orbital is assymmetric about the intramolecular axis and hence it is ungerade. The nodal plane is on the intramolecular axis, and electron density is located above and below this plane.

This molecular orbital is the unoccupied antibonding orbital from the head-on overlap of 2p orbitals of opposite phase. As such, the orbitals oberlap in such a way that there is a nodal plane in the centre between the two nuclei, and a nodal plane on each of the nuclei. This is thus an antibonding orbital. As it is not occupied, it is the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital [LUMO].

Extra Molecule: SiOH2 Molecule

Summary of optimisation results

| Molecule | SiOH2 |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final energy E(RB3LYP) | -365.90001403 |

| RMS gradient | 0.00000941 |

| Point group | CS |

| Si=O bond length | 1.53172 Å |

| Si-H bond length | 1.48652 Å |

| O-Si-H bond angle | 124.156° |

| H-Si-H bond angle | 111.686° |

Item Table

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000023 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000009 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000023 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000017 0.001200 YES

The optimisation file is linked to here

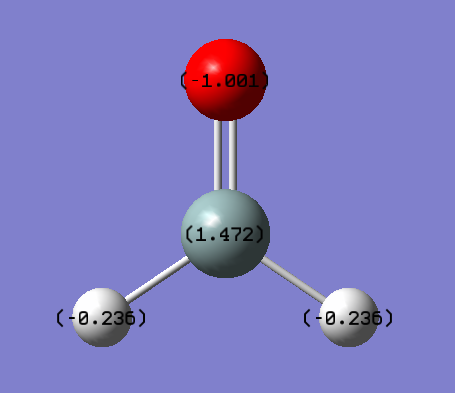

3D visualisation of SiOH2

Optimized F molecule |

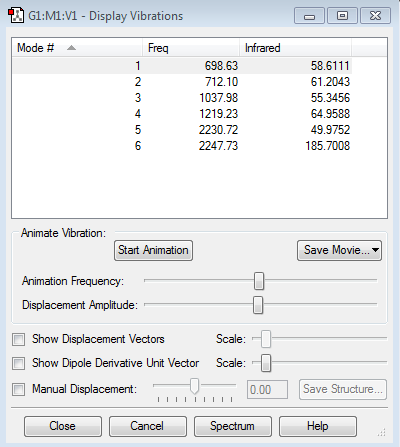

Vibration modes of SiOH2 Molecule

Distribution of charges of SiOH2 Molecule

Interestingly, hydrogen has a negative charge distribution of -0.236. This is because Si has a lower electronegativity (1.9)[3] of compared to H (2.2), hence electron density is drawn towards H, and hence it acts as a hydride here.