Rep:Mod:cn1c

Molecules were drawn on Avogadro and force field of MMFF94s using the Steepest Descent algorithm with 500 steps and convergence of 10e-7. Avogadro was preferred over ChemBiodraw3D due to, although initial difficulties were experienced with the operation of the program, particularly drawing molecules, once familiarised, the twisting and rearranging of molecules to different conformers was much easier on Avogadro.

Computational methods have become central to chemistry demonstrated by the Nobel prize in Chemistry in 1998 for the development of computational methods and the density functional theory to Pople and Kohn[1] and then more recently the 2013 Nobel prize going to Karplus, Levitt and Warshel for their development of the method and the application to more complex systems. [2]

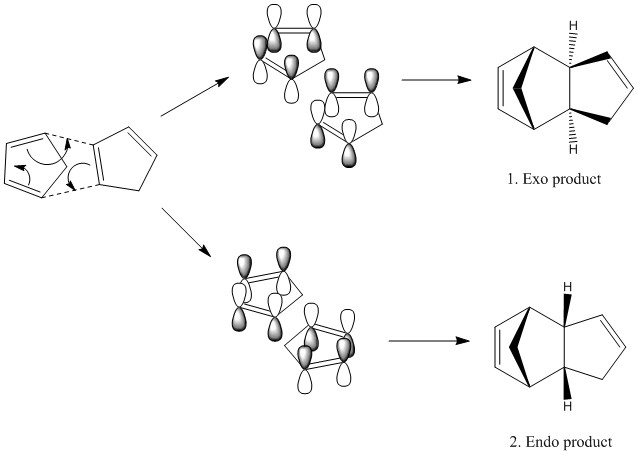

Investigations into the cyclopentadiene dimer

When cyclopentadiene dimerises it is a 4n+2 electron thermal process (where n=1) which proceeds via a Huckel transition state and is suprafacial which is under orbital control. Cyclopentadiene is very prone to cycloadditions as it is locked into the s-cis conformation and so ready for reaction, hence if cyclopentadiene is wanted it must be 'cracked' which causes the retrocycloaddition back to the monomer. Depending upon the orientation of the dienophile in the reaction two products are possible- endo and exo.

Scheme 1. Cyclopentadiene dimerisation

| Stretch (kcal/mol) | Bend (kcal/mol) | Stretch bend (kcal/mol) | Torsion (kcal/mol) | Out of plane bending (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals (kcal/mol) | Electrostatic (kcal/mol) | Total (kcal/mol) | |

| Product 1 | 3.54302 | 30.77273 | -2.04138 | -2.73113 | 0.01485 | 12.80164 | 13.01372 | 55.37344 |

| Product 2 | 3.46681 | 33.20178 | -2.08203 | -2.94509 | 0.02178 | 12.35093 | 14.17742 | 58.1916 |

| Difference | 0.07621 | -2.42905 | 0.04065 | 0.21396 | -0.00693 | 0.45071 | -1.1637 | -2.81816 |

Table 1. Calculated energies of the endo and exo products of cycloaddition

Thus it can be seen that the two isomers are close in energy but the exo product is slightly lower in energy. The greatest contribution in the difference of the two isomers is the bend of the molecules. This is unsurprising due to the fact that larger groups generally tend to prefer to be equatorial as they avoid 1,3 diaxial clashing. However, the endo product is preferentially formed due to stabilising secondary orbital interactions in the transition state. Thus, although the product is higher in energy the barrier to reaction is lower and so forms faster. This is due to the reaction being under kinetic control. The energy of transition states can be calculated to a good degree of accuracy to predict the ratio of product formed. This was done later to determine the configuration of epoxides.

Next the hydrogenation of the endo cyclopentadiene dimer was investigated. With two double bonds and assuming stoichiometric reducing agent only one double bond will be reduced. The stability of the two possible products was calculated using Avogadro.

Figure 1. Different hydrogenation products of the cyclopentadiene dimer

| Stretch (kcal/mol) | Bend (kcal/mol) | Stretch bend (kcal/mol) | Torsion (kcal/mol) | Out of plane bending (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals (kcal/mol) | Electrostatic (kcal/mol) | Total (kcal/mol) | |

| Product 3 | 3.30833 | 30.86455 | -1.92666 | 0.05915 | 0.01536 | 13.28112 | 5.12099 | 50.72283 |

| Product 4 | 2.82234 | 24.68751 | -1.6567 | -0.37519 | 0.00028 | 10.63233 | 5.14705 | 41.25762 |

| Difference | 0.48599 | 6.17704 | -0.26996 | 0.43434 | 0.01508 | 2.64879 | -0.02606 | 9.46521 |

Table 2. Different energies of the hydrogenated cyclopentadiene dimer

Here the bending of the two molecules is the major difference in the overall greater stability of product 4. This is probably due to the nearness of the double bond to the bridgehead in product 3 resulting in a very rigid structure with very high bending energy.

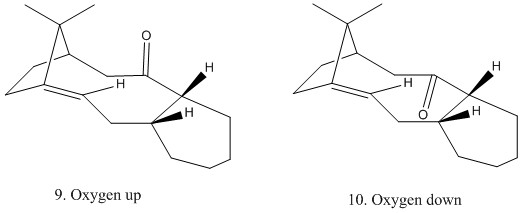

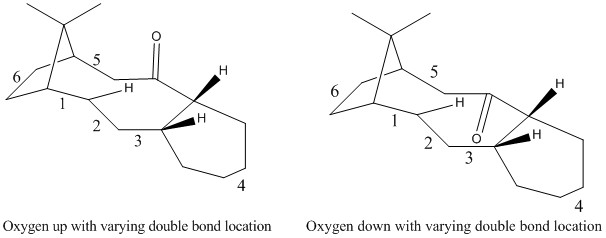

Taxol is a key anti cancer drug and its total synthesis is one of the successes of organic syntheses. As part of the synthesis proposed by Paquette in 1994 involves the synthesis of the carbonyl group up or down. [3] However, due to the lower energy of the carbonyl group pointing downwards, over time the carbonyl rearranges to this more stable conformation. Below are the calculated energy differences.

Figure 2. Taxol like intermediates

| Stretch (kcal/mol) | Bend (kcal/mol) | Stretch bend (kcal/mol) | Torsion (kcal/mol) | Out of plane bending (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals (kcal/mol) | Electrostatic (kcal/mol) | Total (kcal/mol) | |

| 9. Oxygen up | 7.67926 | 28.27323 | -0.07828 | 0.22013 | 0.98634 | 33.16339 | 0.2964 | 70.54047 |

| 10. Oxygen down | 7.594 | 18.80313 | -0.14357 | 0.23728 | 0.85238 | 33.26422 | -0.05534 | 60.55211 |

| Difference | 0.08526 | 9.4701 | 0.06529 | -0.01715 | 0.13396 | -0.10083 | 0.35174 | 9.98836 |

Table 3. Difference in energies of the Taxol like intermediates

This shows again that almost all of the stabilisation comes from the bending. Both of the cyclohexyl rings in the products are both chairs indicating the lowest available conformation. However, with the oxygen down there is also favorable overlap of a C-H σ and C-O σ*. The C-O σ* is a low energy acceptor which can align approximately antiperiplanar to the C-H σ, which according to Kirby's Theory is the most preferred conformation. Using the Klopman Salem equation it can be rationalised that this results in a large stabilisation energy. Using Deslongchamps theory the benefit of this and the chair in oxygen down product results in an overall favoured conformation.

Bond angle analysis was also done. With the oxygen up, the sp2 C has a bond angle of 117.5. This 2.5° deviation from the ideal 120° bond angle may be accountable for the higher energy due to the higher bending energy as the bond is already strained and any further bending may result in steric clashes between the oxygen and the hydrogen off the methyl which is 2.82 Å away. Interestingly, the vicinal hydrogen off the tertiary carbon has a proton at 96.5° and so would be easily deprontated via donation of the C-H σ into the C=O π*. With the oxygen down the bond angles are found to be much closer to the optimum 120°.

The above compounds are part of a sub class known as hyperstable alkenes.[4] These compounds contrary to Bredt's rule, are olefins to bridgeheads which in fact are unusually stable. This is due to the olefins existing in a cage structure and the hydrogenated alkene actually being higher in energy and so hydrogenation is unfavourable. There existence can be confirmed, experimentally, by their slow reaction times as well as calculations on regioisomers with the double bond moved away from the bridgehead.

Figure 3. Regioisomers of 9 and 10

| Double bond location with oxygen down | ||

| Total Energy (kcal/mol) | Difference (kcal/mol) | |

| 1 | 60.55211 | 0 |

| 2 | 74.00018 | 13.44807 |

| 3 | 80.31338 | 19.76127 |

| 4 | 72.86965 | 12.31754 |

| 5 | 88.03204 | 27.47993 |

| 6 | 68.10935 | 7.55724 |

Table 4. Energies with changed double bond locations and oxygen down

| Double bond location with oxygen up | ||

| Total Energy (kcal/mol) | Difference (kcal/mol) | |

| 1 | 70.54047 | 0 |

| 2 | 79.04601 | 8.50554 |

| 3 | 88.02969 | 17.48922 |

| 4 | 78.32293 | 7.78246 |

| 5 | 84.49349 | 13.95302 |

| 6 | 72.66672 | 2.12625 |

Table 5. Energies with changed double bond locations and oxygen up

As shown above the energy is minimised for both oxygen positions with the double bond at the bridgehead position, confirming that the location of the double bond results in a hyperstable alkene. However, it is noted that the whilst the absolute energy ordering is the same for the location of the double bonds, with the exception of location 5, the relative increase is not constant. This suggests that simply changing the location of the double bond can result in a long distance interaction with the carbonyl, depending upon its orientation, affecting the overall energy.

In location 5 the compound is in fact an α-β unsaturated ketone. The reason for the exceptionally high energy of this regioisomer with the oxygen down may be attributed to only two stabilising interactions between the two bonding electrons in a C-H σ orbital rather than 4 as only one C-H is in the correct orientation to overlap with the C-O σ*. To compound this, the other adjacent oxygen is clashing with the oxygen of the carbonyl being only 2.3 Å away and being almost perfectly eclipsed.

Spectroscopic Simulations using Quantum Mechanics

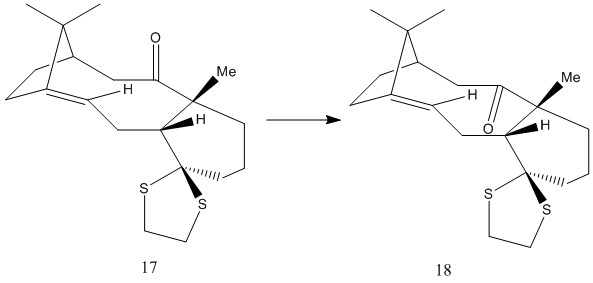

The oxygen down compound 10 was modified by inclusion of a methyl instead of a hydrogen up from the cyclohexyl ring, adjacent to the carbonyl as well as the addition of a dithiane ring. Shown below is compound 18, which is an intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol.

Scheme 2 Taxol intermediate

Energy was minimised using the MMFF94s force field and found to be 100.44 kcal mol-1. It is interesting to note that this is much higher than analogous molecule 10. This can be attributed to the dithiane ring but it is also worth noting that one of the antiperiplanar C-H to the ketone has been replaced by a methyl C-C. This is a lower energy donor than C-H and so via the Klopman-Salem equation the resulting stabilisation energy is less. This is reflected in the shorter C-C bond as the degree of donation increases the enolate like resonance appearance. With a C-H σ donor in 10 the C-C bond length is 1.536 Å whilst with a C-C σ donor in 18 the C-C bond length is 1.562 Å. This supports the resonance form with a C=C double bond.

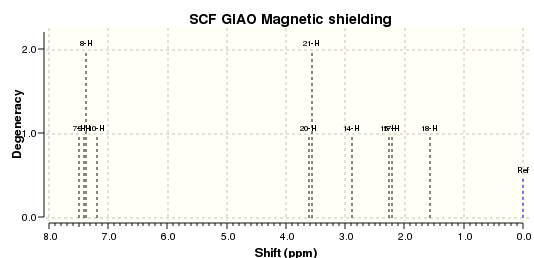

The optimised structure 18 was then submitted to Gaussian to calculate the NMR in benzene for comparison with the literature. The B3LYP theory was used and the 6-31G(d,p) basis. dispersion attractions were included by appending the empirical dispersion= GD3. This was submitted to the high performance computer (HPC) for calculation.

Computed NMR data for compound 18 [5]

| Literature 1H[6] | Collected computed values 1H | Averaged lit values | Averaged comp values | Diff | % diff |

| 5.21 (m, 1 H) | 5.97 | 5.21 | 5.97 | -0.76 | -14.58733205 |

| 3.00-2.70 (m, 6 H) | 3.12, 3.12, 2.95, 2.95, 2.89, 2.8 | 2.85 | 2.971666667 | -0.121666667 | -4.269005848 |

| 2.70-2.35 (m, 4 H) | 2.8, 2.67, 2.54, 2.54 | 2.53 | 2.6375 | -0.1075 | -4.249011858 |

| 2.20-1.70 (m, 6 H) | 2.43, 2.31, 2.31, 1.98, 1.98, 1.83 | 1.95 | 2.14 | -0.19 | -9.743589744 |

| 1.58 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1 H) | 1.83 | 1.58 | 1.83 | -0.25 | -15.82278481 |

| 1.50-1.20 (m, 3H) | 1.64, 1.53, 1.53 | 1.35 | 1.566666667 | -0.216666667 | -16.04938272 |

| 1.10 (s, 3 H) | 1.53, 1.34, 1.27 | 1.1 | 1.38 | -0.28 | -25.45454545 |

| 1.07 (s, 3 H) | 1.21, 1.21, 0.96 | 1.07 | 1.126666667 | -0.056666667 | -5.295950156 |

| 1.03 (s, 3 H) | 0.96, 0.9, 0.6 | 1.03 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 20.38834951 |

Table 6.

| Literature 13C | Computed 13C | Difference | % Diff |

| 211.49 | 211.92 | -0.43 | -0.203319306 |

| 148.72 | 147.87 | 0.85 | 0.571543841 |

| 120.9 | 120.13 | 0.77 | 0.636889992 |

| 74.61 | 92.84 | -18.23 | -24.43372202 |

| 60.53 | 65.94 | -5.41 | -8.937716835 |

| 51.3 | 54.93 | -3.63 | -7.076023392 |

| 50.94 | 54.76 | -3.82 | -7.499018453 |

| 45.53 | 49.53 | -4 | -8.785416209 |

| 43.28 | 48.04 | -4.76 | -10.99815157 |

| 40.82 | 45.65 | -4.83 | -11.83243508 |

| 38.73 | 44.01 | -5.28 | -13.63284276 |

| 36.78 | 41.47 | -4.69 | -12.75149538 |

| 35.47 | 38.51 | -3.04 | -8.570623062 |

| 30.84 | 33.69 | -2.85 | -9.241245136 |

| 30 | 32.47 | -2.47 | -8.233333333 |

| 25.56 | 28.36 | -2.8 | -10.95461659 |

| 25.35 | 26.5 | -1.15 | -4.536489152 |

| 22.21 | 24.45 | -2.24 | -10.08554705 |

| 21.39 | 24.01 | -2.62 | -12.24871435 |

| 19.83 | 22.58 | -2.75 | -13.86787695 |

Table 7.

It is interesting to note that despite a very strong R2 for both NMR graphs suggesting a very high correlation between experimental and computed values upon further inspection the percentage difference is quite marked, in particular for the proton NMR with up to 25% difference in calculated values. The 13C NMR is better matched with percentage differences in calculated shifts not more than 14%. However, this still shows an inherent disparity which was pointed out by Bland and Altman in which correlation may not signify agreement. As such Bland Altman plots could have been used to determine the agreement of the two methods. [7]

The total Gibbs free energies of the products 17 and 18 can also be investigated using Gaussian. This was resolved to be -1651.438451 Ha for 17 [8] and -1651.462137 Ha for the 18. This correlates to a ΔG= -62.187584 kJ/mol. This shows that conformer 18 is more stable and that is direction of the forward reaction. Using the Gaussian Checkpoint files the two molecules, with oxygen up and down, also had their dipole moment calculated. With oxygen up it was calculated to be 3.93 Debeye. Conversely with oxygen down, the dipole moment was calculated to be 1.8269 Debeye. This may also be a contributing factor in the overall stabilisation and general preferred conformation of the molecule as molecules attempt to minimise their dipole.

In order to try and find calculated results that closer matched those in the literature the conformation of the cyclohexene ring was distored from its optimum chair to a boat conformation which was then submitted to the HPC for calculation of the NMR.

NMR data of 18 in boat conformation [9]

Computed 1H NMR for the boat conformation

Computed 13C NMR for the boat conformation

| Averaged lit values | Averaged comp values | Diff | % Difference |

| 5.21 | 5.38 | -0.17 | -3.26296 |

| 2.85 | 2.908 | -0.058 | -2.03509 |

| 2.53 | 2.26 | 0.27 | 10.67194 |

| 1.95 | 1.93 | 0.02 | 1.025641 |

| 1.58 | 1.77 | -0.19 | -12.0253 |

| 1.35 | 1.58 | -0.23 | -17.037 |

| 1.1 | 1.42 | -0.32 | -29.0909 |

| 1.07 | 1.1 | -0.03 | -2.80374 |

| 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.01 | 0.970874 |

Table 8.

| Literature 13C | 13C Computed NMR | Difference | % Difference |

| 211.49 | 212.24 | -0.75 | -0.35463 |

| 148.72 | 148.9 | -0.18 | -0.12103 |

| 120.9 | 118.55 | 2.35 | 1.943755 |

| 74.61 | 89.06 | -14.45 | -19.3674 |

| 60.53 | 67.58 | -7.05 | -11.6471 |

| 51.3 | 56.31 | -5.01 | -9.76608 |

| 50.94 | 55.54 | -4.6 | -9.03023 |

| 45.53 | 50.09 | -4.56 | -10.0154 |

| 43.28 | 46.82 | -3.54 | -8.1793 |

| 40.82 | 44.47 | -3.65 | -8.9417 |

| 38.73 | 41.3 | -2.57 | -6.63568 |

| 36.78 | 37.68 | -0.9 | -2.44698 |

| 35.47 | 36.28 | -0.81 | -2.28362 |

| 30.84 | 32.08 | -1.24 | -4.02075 |

| 30 | 29.07 | 0.93 | 3.1 |

| 25.56 | 58.7 | -33.14 | -129.656 |

| 25.35 | 25.86 | -0.51 | -2.01183 |

| 22.21 | 25.21 | -3 | -13.5074 |

| 21.39 | 23.28 | -1.89 | -8.8359 |

| 19.83 | 21.74 | -1.91 | -9.63187 |

Table 9.

Thus it can be seen that on average the literature values and the computed values in the boat form are in better agreement, albeit one anomalous result in each, with 30% and 130% percentage difference between the computed and literature values. In both cases the prediction is for a much more deshielded environment and may be due to the presumed exerted influence of nearby sulphur atoms. This is supported by the numbering of the atoms which indicate the most erroneous atom assignments are adjacent to the dithiane ring.

Interestingly, the free energy calculated from the Gaussian log file for the boat is actually lower than that of the chair. Albeit small, this suggests that the boat conformer is actually favored in contrast to the usual convention that the chair is the lowest energy conformation. The energy difference between the two was calculated to be 1.698 kJ mol-1. This corresponds to a K value of 1.98 at room temperature. As mentioned, this is a small preference but still unusual. This could be due to the dithiane interactions or differences between state in solid and liquid where the boat may be solvent stabilised. Unfortunately, the free energy of the twist boat could not be calculated to see if this was even more stable as calculated for other cyclohexane rings with large substituents. [10]

Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

Chiral synthesis has developed greatly recently with the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2001 being rewarded to Knowles, Noyori and Sharpless for their work on chirally catalysed hydrogenation and oxidation reactions respectively.[11] Recently chiral epoxidation methods have been developed including the use of the Jacobsen catalyst [12] and Shi catalyst [13]. These were synthesised previously in the lab and then used to catalytically epoxidise two alkenes. Here the resulting epoxides absolute configurations are assigned using computational methods to investigate catalyst active sites and transition state energies.

NMR analysis of epoxides

NMR Data for 1,2 dihydronapthalene oxide [14]

Computed 1H NMR

Computed 13C NMR

| Computed 1H NMR | Literature 1H NMR [15] | Computed 13C NMR | Literature 13C NMR |

| 7.49 (1H) | 7.28 (1H) | 133.84 | 136.7 |

| 7.39 (2H) | 7.08-7.17 (2H) | 130.38 | 132.6 |

| 7.2 (1H) | 6.98 (1H) | 125.55 | 129.5 |

| 3.59 (2H) | 3.74 (1H) | 123.84 | 128.4 |

| 2.88 (1H) | 3.62 (1H) | 123.43 | 128.4 |

| 2.68 (1H) | 2.68 (1H) | 121.44 | 126.1 |

| 2.22 (1H) | 2.44 (1H) | 56.44 | 55.1 |

| 1.56 (1H) | 2.30 (1H) | 54.83 | 52.7 |

| 1.65 (1H) | 28.04 | 24.4 | |

| 24.95 | 21.8 |

Table 10.

This shows good agreement between the computed and literature values. The only real disparity for the 1H NMR is the computed value for two hydorgens to be at 3.59 ppm when according to the literature they are in fact at 3.74 ppm and 3.62 ppm. The 13C NMR is also in very good agreement with the computed values. Particularly impressive is the prediction of the essentially equivalent peaks computed at 123 ppm and in literature quoted at 128.4 ppm.

NMR Data for trans-β-methyl styrene oxide [16]

Computed 1H NMR

Computed 13C NMR

| Computed 1H NMR | Literature 1H NMR [17] | Computed 13C NMR | Literature 13C NMR |

| 7.49 (3H) | 7.39-7.24 (5H) | 134.98 | 135.84 |

| 7.42 (1H) | 3.57 (1H) | 124.07 | 128.3 |

| 7.31 (1H) | 3.40-3.32 (1H) | 123.33 | 127.7 |

| 3.42 (1H) | 1.45 (3H) | 122.8 | 125.7 |

| 2.79 (1H) | 122.73 | 59.7 | |

| 1.68 (1H) | 118.49 | 59.7 | |

| 1.59 (1H) | 62.31 | 18.1 | |

| 0.72 (1H) | 60.59 | ||

| 18.84 |

Table 11.

The deshielded protons show good agreement between the computed values and literature values with the five most deshielded hydrogens computed hydrogens broadly falling within the experimental values. However the more shielded protons show some disparity in particular the one of the hydrogens being predicted at 0.72 ppm when experimentally it is found to be about 1.45 ppm. However, the other two values of 1.68 ppm and 1.59 ppm are not bad matches. The particularly low predicition may be due to restricted rotation predicted leading to not only 3 distinct environments but one proton also being significantly more shielded than the other two. The 13C NMR again agrees generally with the computed values. However, the literature cites only 7 carbon environments whilst computed, and using common sense, there are 9 carbon environments. It is most likely that the two signals are hidden behind peaks and the authors have not quoted the values twice in the literature. It is most likely aromatic carbons behind the 125.7 ppm and 127.7 ppm peaks.

Optical rotation

One way of determining the absolute configuration of the epoxides made is the comparison of their optical rotation with literature values. Two enantiomers will have equal and opposite values for their optical rotatory power. Unfortunately, the literature reported values are widely varied. However, although their magnitude is of some interest only their absolute sign is relevant for determining their absolute configuration. It was found that values ranged for the S,S configuration of trans-β-methyl styrene from -15.6° [18] to - 116°[19]. The R,R enatiomer was drawn and found to have a calculated value of 47.00°. [20] For 1,2 dihydronapthalene oxide the S,R conformer was calculated and found to have a value of -155.79.[21] In the literature the value for the R,S conformer was found to be range from 126°[22] to 133°. [23] Thus it can be seen that not only do the values for the calculated enantiomers have different signs to their opposing enantiomers in literature, they are even of similar magnitudes. This is very impressive, particularly in the case of trans-β-methyl styrene which has a predicted value in the range of literature values and isn't even a particualrly large number indicating impressive sensitivity.

Catalysts

Jacobsen catalyst synthesis and use for epoxidation [24]

Scheme 3. Jacobsen synthesis and epoxidation method

The Jacobsen catalyst crystal structure was investigated using Mercury. Viewing the Jacobsen catalyst using the space filing model it is apparent that the Jacobsen catalyst is selective for Z alkenes. with huge steric bulk preventing sideways approach and the active site protruding from the Salen ligand plane it is clear that the alkene must be cis to reach the active site or face serious steric hinderance.

Looking at distances between groups shows that due to the steric shielding afforded by the tert-butyl groups results in a gap of around 3 Å, with the distance between adjacent hydrogens in ethene being just under 2.5 Å, it can be seen the sideways approach will encounter extreme steric hindrance.

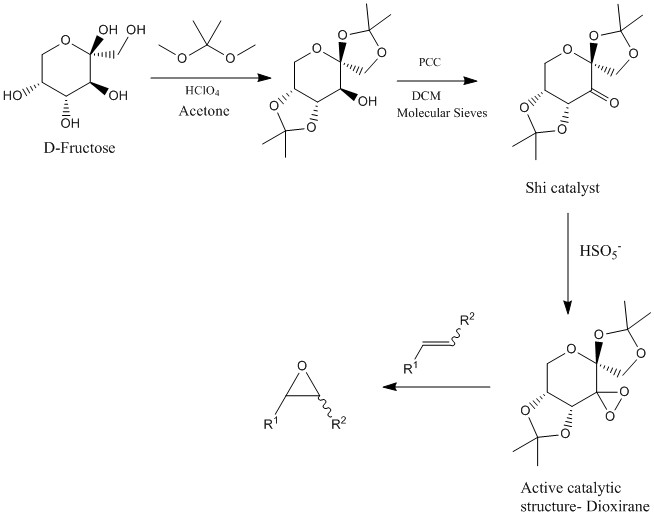

Shi catalyst synthesis and use for epoxidation [25]

Scheme 4. Shi Catalyst and epoxidation method

Shi Catalyst

The Shi catalyst was investigated with specific focus on the C-O bond lengths. C-O σ* is a good acceptor and whilst the lone pair on adjacent oxygen is a high energy donor. This results in a favourable overlap and so is responsible for the anomeric effect, in which despite steric constraints sugars often prefer the α anomer with the C-O axial. Interestingly, there a numerous C-O σ* antiperiplanar to lone pairs resulting in numerous bond shortenings and lengthenings. The four C-O bonds in the five membered acetal ring off the sugar backbone vary in length from 1.46 Å to 1.405 Å. This is due available overlaps resulting in double bond- no bond resonance forms. The long 1.46 Å bond is due to a antiperiplanar C-O σ* but no double bond resonance. The axial C-O is not particularly long due to the oxygen lone pair being able to donate into the C-O σ* that is part of the sugar backbone. This corresponds to a lengthening of the bond which counteracts the characteristic anomeric shortening resulting in a normal C-O bond length.

Closer inspection at the crystal structure of the Shi catalyst can give insight into its selectivity. The active species is a dioxirane ring orthogonal to the sugar ring. As shown below, it can be seen that trans alkenes can orientate themselves correctly to avoid clashing with the methyl groups off five membered acetal rings which exist above and below the plane of the sugar ring and are all less than 3 Å away.

Transition state analysis

The HPC was used to calculate energies of the transition states leading to the synthesised epoxides using both Jacobsen and Shi catalysts. This was able to discern the absolute configuration of the tetrahedral centers via calculation of the transition states energies leading to the products.

In order to calculate the absolute configurations the relative energies of the transitions states en route to each product. As the two possible products are enantiomers they by definition have the same free energy but us of a chiral catalyst can ensure the energy of a transition state to one of the products is lower and so formed preferentially.

This is comparable to the cycloaddition of cyclopentadiene.

Due to the great number of molecules involved in the transition states and therefore the long computational times required transitions states were given calculated. However, due to the different approaches possible by the molecules and in the case of the Shi catalyst the difference between the two oxygens in the dioxirane, the many different possible transitions states were analysed via the sum of electronic and thermal free energies to determine the lowest free energy for each enantiomers approach and consequently the equilibrium constant between enantiomers. It is reasonable to assume that for the formation of all enantiomers the reaction would proceed via the lowest energy pathway and so for each enantiomer these were analysed.

| Shi trans beta methyl styrene | |||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies (Ha) | |||||

| RR [26] | SS [27] | Difference | dG (kJ/mol) | ln K | K |

| -1343.032443 | -1343.024742 | -0.007701 | -20.1289 | 8.16 | 3501 |

Table 11.

| 1,2 dihydronapthalene Jacobsen | |||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies (Ha) | |||||

| S,R [28] | R,S [29] | Difference | dG (kJ/mol) | ln K | K |

| -3421.369033 | -3421.359499 | -0.009534 | -25.03151338 | 10.1 | 24422 |

Table 12.

Thus it can be seen that the R,R configuration is preferred by for epoxidation product of trans beta methyl styrene using the Shi catalyst. Likewise the S,R configuration is preferred by the 1,2 dihydronapthalene epoxide product using the Jacobsen catalyst. It is worth noting that the Jacobsen equilibrium constant is much higher than that for the Shi catalyst and so can be argued to be more selective, demonstrated by its higher enantiomeric excess (ee) values. This is a measure of how much more one enantiomer is present than another. To compensate, the Shi epoxidation in the lab was run at 273 K. This results in a larger ln K and a subsequent K value of 7104, approximately double the equilibrium constant at room temperature. Using the K value the enantiomeric excess can be calculated using:

For the Shi catalyst this represents an ee for R,R of 99.94%. The decreased temperature results in a ee of 99.97%. For Jacobsen the ee of S,R is 99.99%.

Interestingly, use of the Jacobsen catalyst with trans beta methyl stryene through analaysis of the transition states predicts the S,S transition state to be 10.83 kJ mol-1 lower in energy resulting in a K=79.23 and an ee of 97.5%. [30] [31]

'Non Covalent Interactions investigation'

Orbital |

This shows the relative forces within the R,R Shi catalyst transition state with trans-β-methyl styrene. Green represents mild attractive forces. and it shows the numerous stabilising attractive forces in this orientation which lead to this being the lowest energy transition state and so leading to the dominant R,R enantiomeric product. Of particular interest is the hydrogen orientated up adjacent to the dioxirance ring which interacts favorably with the benzene ring. Also generating a large stabilising interaction is the methyl, off the double bond, interacting with the 5 membered acetal ring off adjacent to the dioxirane ring. Also of interest is the multicolored ring off the dioxirane where the bond can be seen to start to form as blue indicates very attractive interactions- the birth of the new bond.

Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

Another method for visaulising interactions within the transition state is with QTAIM to investigate the electronic topology. The dotted yellow lines with yellow balls represent interactions. However, this method is slightly less useful as it does not show the magnitude of attractive forces nor does it give a good 3D smearing of the interactions but represents them as point interactions. However, this still shows the same main attractive forces namely between the hydrogen of the catalyst and the benzene ring, shown on the right, as well as the methyl interacting with the acetal ring, shown on the left.

Alternate candidate for epoxidation

A possible expansion of the experiment for epoxidations would be to epoxidise cis-stilbene. Trans stilbene was used in the experiment but the change in the geometry of the double bond would allow for more quantitative and comparable results in the different transition states of the catalysts, in particular their steric requirements. There is no reported values for the optical rotation in the literature and thus calculated values would have to be compared to students own experimental findings.

References

- ↑ http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1998/

- ↑ http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/2013/

- ↑ L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI|10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ C. Nielsen, Compound 18, D-space, DOI:10042/27506

- ↑ ↑ L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ J.M Bland and D.G Altman, Stat Methods Med Res, 1999 8, 135, DOI:10.1177/096228029900800204 10.1177/096228029900800204

- ↑ C. Nielsen, Compound 17, D-space, DOI:10042/27505

- ↑ C, Nielsen, Compound 18 in boat, D-space DOI:10042/27498

- ↑ G. Gill, D.M. Pawar, E.A. Noe.,,J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 10726-10731 DOI:10.1021/jo051654z

- ↑ http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/2001/

- ↑ E. N. Jacobsen , W. Zhang , A. R. Muci ,J. R. Ecker , L. Deng J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 7063–7064; DOI:10.1021/ja00018a068

- ↑ O. A. Wong , B. Wang , M-X Zhao and Y. Shi J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74, 335–6338; DOI:10.1021/jo900739q

- ↑ C. Nielsen, 1,2 Dihydronapthalene oxide, D-Space DOI:10042/27503

- ↑ K.Smith, C. Liu, G. A. El-Hiti, Org. Biomol. Chem., 2006,004, 917-927 DOI:10.1039/b517611p 10.1039/b517611p

- ↑ C. Nielsen, trans-β-methyl styrene oxide, D-space DOI:10042/27504

- ↑ P.C Bulman Page, P. Parker, B. Buckley, G. A. Rassius, D. Bethell, Tetrahedron, 2009, 65, 2910–2915DOI:10.1039/B517611P 10.1039/B517611P

- ↑ Feiten, Hans-Juergen; Hofstetter, Karin; Hollmann, Frank; Schmid, Andreas; Witholt, Bernard Advanced Synthesis and Catalysis, 2001 , 343, 732 - 737

- ↑ Fourneau; Benoit Bulletin de la Societe Chimique de France, 1945 , 5, 985,988

- ↑ C. Nielsen, trans-β-methyl stryene optical roation, D-space DOI:10042/27535

- ↑ C. Nielsen, 1,2 dihydronapthalene oxide optical rotation, D-space {{DOI|10042/27534}

- ↑ Akhtar; Boyd 'Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications,' 1975 , 916

- ↑ Boyd, Derek R.; Sharma, Narain D.; Agarwal, Rajiv; Kerley, Nuala A.; McMordie, R. Austin S.; et al.Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications, 1994 , 14, 1693 - 1694

- ↑ J. Hanson,J. Chem. Educ., 2001, 78, {DOI|:10.1021/ed078p1266}

- ↑ A. Burke , P. Dillon , Kyle Martin and T. W. Hanks,"Catalytic Asymmetric Epoxidation Using a Fructose-Derived Catalyst", J. Chem. Educ., 2000, 77, 271; DOI:10.1021/ed077p271

- ↑ H. S. Rzepa, Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7, Figshare, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.738037

- ↑ H.S. Rzepa, Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.739117

- ↑ H.S Rzepa, Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3, Figshare, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.740436

- ↑ H. S Rzepa, Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3, Figshare, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.783898

- ↑ H.S. Rzepa,Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3, Figshare, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.856650

- ↑ H.S, Rzepa, Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3, Figshare, 2013 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.856651