Rep:Mod:clras13

Module 2: Bonding

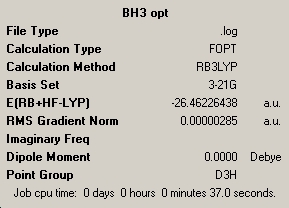

BH3

|

Bond Angle (B-H, Å) |

|---|---|

| 1.19425 | |

| Bond Angle (H-B-H, °) | |

| 120.000 |

Gradient

A gradient is the rate of change of one variable with respect to another i.e. first derivative of the function (dy/dx). For instance as the number of optimisation steps increases, the rate of change in the total energy of the molecule decreases (a negative slope). As this value approaches (and reaches) 0, no matter how many more steps are run the total energy will not change and hence a energy maximum or minimum has been reached (determined by the second derivative - d2y/dx2).

Bond Definition

A bond can be defined as the sharing of a pair of electrons between two atoms. This interaction arises when the two atoms are brought sufficiently close together but internuclear repulsion maintains an optimum distance between the two atoms. The distance required for the bond varies according to the molecular orbitals involved in the interaction. The smaller and less diffuse the orbitals involved, the shorter the bond distance.

In Gaussview, however, the last point (regarding the distance for bonds varying) is not taken into account. A set distance is defined at which point Gaussview draws a formal bond. Any distance beyond this and a bond is not seen despite the interactions between the atoms being taken into account by the program.

Vibrational Analysis

The vibrational analysis was obtained via a Frequency/DFT/B3LYP/3-21G setting with additional text pop=full.

The irreducible representation labels are determined by taking the vibrations as objects and subjecting them to the operations of the D3h group and comparing to the character table. The values for degenerate vibrations are determined by taking a sub group of the point group such as C2v and then applying the operations to the vibrations. This removes degeneracy since there are fewer axes for example. The sum of the values for the degenerate vibrations represents the irreducible representation in the D3h point group. As it can be seen there are two pairs of degenerate vibrations and hence whilst there are 6 vibrations, only four peaks are seen expected in the I.R. spectrum.

There are however only three peaks. This is because the one of the peaks (2592.79cm-1) has an intensity of 0. Hence it is not observed. The pair of degenerate vibrations' (1204.66cm-1 and 2731.31cm-1) intensities stack and hence appear as only two peaks. This is combined with the singly degenerate peak at 1145.71cm-1 causing only three peaks in the I.R. spectrum.

I.R. Spectrum

|

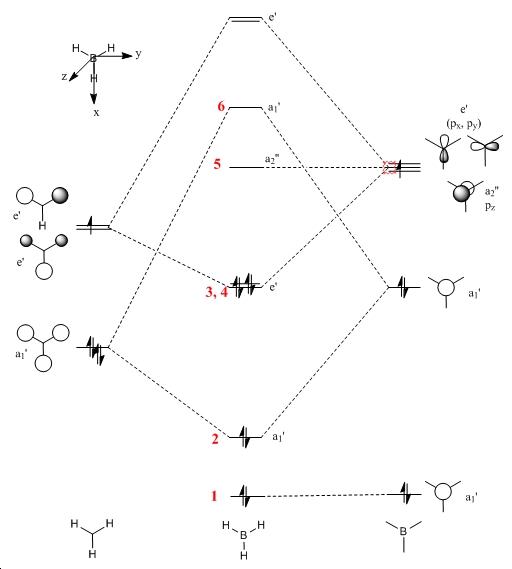

Molecular Orbitals

The molecular orbitals were obtained via a optimisation/DFT/B3LYP/3-21G basis set with the additional text pop=full.

| Molecular Orbital Diagram | Number | Qualitative M.O. | Quantitative M.O. |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 6 |

|

| |

| 5 |

|

| |

| 4 |

|

| |

| 3 |

|

| |

| 2 |

|

| |

| 1 |

|

|

The difference between the qualitative and quantitative M.O.s are very small. All occupied molecular orbitals match up very well. The main differences arise from the unoccupied molecular orbitals. In the case of the LUMO, the orbitals are of the same type as the qualitative LUMO (p-orbital shape), but it is also far more diffuse and appears to cover the H atoms as well. This is a similar case for the LUMO+1, which results in the major s orbital on the B atom being squeezed by the out of phase H atom S orbitals. This is difference arises from the fact that a lack of occupancy of the orbitals causes changes to the calculations. Hence the difference when considering reactivity is not that great. Electrophilic attack on the molecule would still proceed as expected by the qualitative and quantitative M.O. diagrams - i.e. at the vacant p orbital on the B atom. The accurate modelling of the occupied M.O. also indicates that if Bh3 could act as a nucleophile it would react as expected from qualitative M.O. theory. Hence this implies the qualitative M.O. theory is very accurate and useful in making predictions about the reactivity of a molecule.

BCl3

|

Bond Angle (B-Cl, Å) |

|---|---|

| 1.87000 | |

| Bond Angle (Cl-B-Cl, °) | |

| 120.000 |

CF4[1]

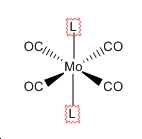

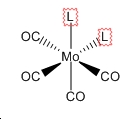

Mo(CO)4L2 Isomers

The method for optimisation of the structures in this section was three fold. Firstly a optimisation/DFT/B3LYP/LanL2MB (with additional text opt=loose) was run. The basis set was then improved to LanL2DZ with the additional text removed before doing the final optimisation whereby int=ultrafine scf=conver=9 was added to the text. The I.R. data was then obtained by keeping the same LanL2DZ basis set but changing the method to frequency and removing the additional text.

Computational methods enable the modelling of compounds that may not have been characterised before. Hence bond distances, angles, vibrations etc. are not always available. Thus to ensure that calculations are not totally incorrect from real life reactions, approximate values are usually determined. This is case for L=pyridine for instance. Prolonged searching (over a day) of the databases returned no crystal or I.R. data.

Another important problem with computational methods is that all I.R. values are inherently flawed (unless a very high level calculation is preformed). B3LYP calculations are off experimental values by approximately 10% due to correlation effects not being taken into account. Furthermore solvation of the molecules is not considered. Hence direct comparison of frequencies between lit. and calc. are not appropriate. However the frequency difference between peaks can be compared as the errors should not have a significant. This from of comparison enables computational chemistry to be very useful in analysing trans effects for instance.

The trans effect also indicates a very important point about distinguishing between the trans and cis system. If the L ligand is trans to a CO ligand there will be two different Mo-C bond lengths. This is due to the electronegativety , π donor/acceptor quaility of the L ligand (thermodynamic trans effect). If the molecule is a trans with respect to the L groups then this different bond length will not occur as the ligand trans to the CO will be a CO ligand. Furthermore depending on the steric bulk of the L ligands, when the L groups are trans to each other there should be least steric clashes and hence the bond length of the trans isomer Mo-L bond should be smaller than cis Mo-L bonds. These trends are noticeable in the below isomers and support the suggestion accurate optimisation has occurred.

In I.R. analysis of cis and trans ligands a similar pattern should be observed no matter what the L ligand is. This is based upon the pseudo point group of the molecules (by treating the ligands as point charges).

| Trans | Cis |

|---|---|

|

|

| D4h | C2v |

| ГIR=A1g+B1g+Eu[2] | ГIR=2A1+B1+B2[2] |

From these molecules, reducible representations for the vibrations can be determined (as detailed in BH3) which can then be placed in the reduction formula to determine the the irreducible components (as shown in the table above).

Thus for the trans isomer only one peak is seen with two smaller shoulder peaks. This is because the A1g+B1g vibrations do not change sign when the operations of the point group are applied (i.e. the molecule and electron density is symmetrical). However, due to the actual symmetry of the molecules not being the same as the pseudo point group the A1g+B1g vibrations are seen.

The cis isomer should exhibit four peaks with two of them being very similar in frequency (there are two A1 vibrations).

L=PMe3

| Trans | Cis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[4] [4]

|

|

[6] [6]

| ||||||

| Trans C=O stretches (cm-1) | Cis C=O stretches (cm-1) | ||||||||

| Lit.[7] | Calc. (Intensity) | Lit.[8] | Calc. (Intensity) | ||||||

| 1901(s) | 1956.17(4.3056), 1884.69(11.15), 1843.77(1978.38), 1843.42(1973.61) | 2022(m), 1917(s), 1903(s), 1882(s) | 1959.97(369.602), 1873.87(665.766), 1856.56(1047.73), 1851.09(1953.69) | ||||||

All optimisation and I.R. calculation data was obtained from Simon Sung (NB - the advanced addition of d orbitals to the P atom was done in these calculations). All lit. values obtained are for the ligand PR3 (most of the time Ph). This ligand is very similar to the PMe3 ligand and hence the values should be very similar.

| Bond Type | Trans Bond Length Lit. (Å)[9] | Trans Bond Length (Å) | Cis Bond Length Lit. (Å)[10] | Cis Bond Length (Å) |

| Mo-P | 2.500 | 2.524 | 2.522 | 2.589 |

| Mo-C | 2.005, 2.016 | 2.029, 2.028, 2.031, 2.032 | 1.966, 1.975, 2.022, 2.042 | 1.994, 2.032 |

| Bond Type | Trans Bond Angle Lit. (°)[9] | Trans Bond Angle (°) | Cis Bond Angle Lit. (°)[10] | Cis Bond Angle (°) |

| P-M-P | 180.000 | 177.006 | 97.54 | 93.985 |

The vibrations are in accordance with lit and theory in terms of intensity (the actual frequency is different for the reasons mentioned previously). The trans isomer appears to deviate from theory by possessing two strong vibrations but this may be due to an error in the calculation - the difference is only 0.35cm-1. Hence these two peaks are most likely degenerate Eu vibrations.

The bond lengths are (Mo-C) are very similar to lit. (and theoretical reasoning) and show that computational methods are a good approximation. The max deviation from the lit. is ~3%. The pairs of similar Mo-C bond lengths in lit. are roughly the average of the calc. value and hence the number of different bond lengths in not significant (this is most likely due to Jahn-Teller distortions to remove degeneracy and reach a more stable conformation). The Mo-P bond has the most deviation from lit. (~0.07Å) despite d orbitals being taken into account. In terms of bond angle, the difference is most likely due to an inherent error in the calculation as both values in cis and trans are off by 3°. Nonetheless this is only an estimate and hence these values show that the accuracy obtained by the optimisation is as high as possible for the level of calculation.

L=C5H10N-

| Trans | Cis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[12] [12]

|

|

[14] [14]

| ||||||

| Trans C=O stretches (cm-1) | Cis C=O stretches (cm-1) | ||||||||

| Lit. | Calc. (Intensity) | Lit.[15] | Calc. (Intensity) | ||||||

| Unabale to find the compound (but expected number of C=O

stretches [from theory] are present. |

2001.77(0), 1922.33(0.0001), 1901.63(1670.08), 1896.84(1973.45) | 2012(mw), 1913(sh), 1887(s), 1838(s), 1792(sh), 1774(vs) | 1992.43(639.556), 1928.52(483.48), 1907.87(515.347), 1874.38(1847.02) | ||||||

Once again there is good correlation suggesting that this is indeed an accurate optimisation of the structures (there is some deviation but this is due to the fact the modelled ligand is the conjugate base of the lit. [piperidine]).

| Bond Type | Trans Bond Length (Å) | Cis Bond Length (Å) |

| Mo-N | 2.068 | 2.055 |

| Mo-C | 2.066 | 2.050, 2.083 |

The typical Mo-N bond lengths are 2.10Å, 1.84Å and 1.68Å for single, double and triple bonds respectively[16]. From this it can be seen that the bonds in this complex are most similar to single bonds. This is in keeping with theory which suggests the ligand co-ordinates via a lone pair and that there is little π donation to the metal (or acceptance of electron density from the Mo to a π* orbital).

The Mo-C bond lengths are harder to approximate. The trans product (with respect to the L ligands) should possess Mo-C bond lengths which are approximately the same as the PMe3 trans complex (the trans ligand to the C=O is the same in both complexes). This is nearly the case but it is slightly longer. This is most likely due to the electronegativity difference between N and P. N is far more electronegative and hence the Mo-N bonds are shorter than Mo-P bonds causing the sterically smaller C=O ligands to be forced away from the Mo centre. This may also explain why the cis (w.r.t. L ligands) bond lengths (Mo-C) are longer than PMe3. It should be noted that less significance can be placed on the trans effect because the C-Mo-N bond angle is in fact 166.125°. Thus orbital alignment for the trans effect is likely to be poorer.

| Bond Type | Trans Bond Angle (°) | Cis Bond Angle (°) |

| N-M-N | 180.000 | 112.449 |

The trans angle suggests good optimisation since this is the expected angle for most trans products (e.g. see lit. values for PMe3). The cis bond angle is significantly different from the 90° bond angle expected from a perfect octahedral arrangement. This may be due to the steric bulk of the ring system being closer to the metal centre (shorter Mo-N bond) causing the C=O ligands (smaller) to be displaced further to make room for the ligand.

L=Pyridine

The complex modelled cannot be found in lit. despite long hours searching. Hence there are no lit. value. However the number of peaks and intensities does support theoretical predictions (the reason for two strong trans peaks being explained earlier).

| Bond Type | Trans Bond Length (Å) | Cis Bond Length (Å) |

| Mo-N | 2.275 | 2.310 |

| Mo-C | 2.029 | 2.036, 1.977 |

The bond length of the Mo-N is in slightly longer than the normal Mo-N single bond length. This seems to suggest that either the optimisation has not been successful (not likely due to the fact other values match up with approximate values) or that the very high electron density of the aromatic ring system is prevented from approaching the Mo centre by the π electron density of the carbonyl groups. Thus since the pyridine groups cannot approach to the same degree as the conjugate base of piperidine as well as the fact planar pyridine is orientated between two C=O groups, the trans isomer Mo-C bond lengths should be very similar to the PMe3 values - which they are. The cis isomer Mo-C bond lengths should also be similar because the trans effect of pyridine is lower than PMe3. Hence the Mo-N bond in the cis complex should be longer (which it is) and the Mo-C bond should be slightly shorter (which is also the case).

| Bond Type | Trans Bond Angle (°) | Cis Bond Angle (°) |

| N-M-N | 180.000 | 85.519 |

The bond angles are once again as expected from theoretical values. The trans value appears to be consistent with general angle of a trans [Mo(CO)4L2] complex. The cis angle is also very close to 90°. This is unlike the piperdine conjugate base isomers and is expected. The orientation of the pyridine rings is between two C=O ligands (i.e. not parallel with the C=O ligands). Thus there is less steric interactions and a more optimum 90° angle can be approached.

Cis - Trans Energy Differences

| Cis-Trans Energy Difference (kJ/mol) | ||

|---|---|---|

| L=PMe3 | L=C5H10N- | L=Pyridine |

| 3.11 | 6.7375581 | 50.85703771 |

| Strong trans effect | Weak trans effect | Weak trans effect |

| Trans more stable | Cis more stable | Cis more stable |

Whilst the trans effect is kinetically very important in transition state structure it also has an impact on the thermodynamic stability of the complex. The large the difference between the ligands in terms of the trans effect, the longer the M-Lweak trans effect ligand. In the weak trans effect ligand cases (N based ligands above) the cis energy is the lowest. C=O ligands have a strong trans effect. Hence in the cis isomers the electron density is drawn away from the L ligand to the C=O. This must have induce a stabilising force which is not present in the trans isomer (all ligands have the same ligand trans to themselves - thus no trans effect difference)

When the trans effect of the ligand is weak and the ligand is sterically bulky in terms of orientation with respect to the C=O groups, the energy difference is not that great (as shown by C5H10N-). This is due to the C-Mo-N angle being distorted to 166°. Hence there is poorer orbital overlap for the trans effect to occur. This was tested by using L=pyridine. Thus when the ligand is made to be slightly less sterically demanding the complex (as in the case of pyridine - explained previously), it can be seen the energy difference between the two isomers is far greater and the cis isomer is significantly more stable. Hence, if the active catalytic form is the cis Mo(CO)4L2, a weak trans effect L which is sterically small is ideal.

The strong trans effect PMe3 ligand results in the trans isomer being more stable. Hence this suggests to get a more stable trans form of the Mo(CO)4L2 molecule, stronger trans effect L ligands are required. This is because the difference in trans effect between PMe3 and C=O is not great. Thus the stabilising force is not as significant in the cis isomers. Thus this raises the energy of the cis isomer above the trans isomer. To ensure the greatest orbital overlap for the trans effect the L ligand must be sterically smaller.

The stabilising force that is mentioned appears to be connected to the trans effect. However the trend cannot be confirmed with only three different ligands - a wider array of lignds must be modelled and compared to lit. to ascertain the accuracy of this statement and its possible origin.

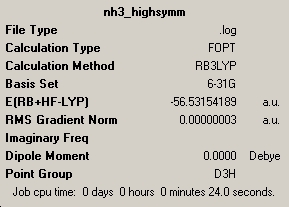

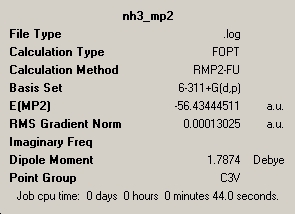

NH3

The following three optimisations were run on a optimisation/DFT/B3LYP/6-31G basis set.

| Point Group | C3v | C1 | D3h |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary |

|

|

|

| Bond Length (Å) | 1.00591 | 1.00595 | 1.00037 |

| Bond Angle (°) | 116.251 | 116.158 | 120.000 |

| Total Energy (kJ/mol) | -148424.4664 | -148424.4709 | -148423.5632 |

| ΔE=E(high energy)-E(low energy)=[(-148423.5632)-(-148424.4709)]= 0.9077kJ/mol | |||

The higher the symmetry, the lower the optimisation time. This is most likely due to the fact that there are fewer geometries for the molecule that conform to higher symmetry molecules. Hence there are fewer optimisation steps.

The lowest energy molecule is the one with C1 symmetry whilst the highest energy molecule is has least symmetry (D3h). In the D3h molecule, orbital mixing can not occur due to the irreducible representation of the orbitals not being the same. However upon vibration of the nuclei, the symmetry is broken and non degenerate orbital mixing occurs of the excited state with ground state (second order Jahn-Teller distortion). This results in a lower energy ground state and hence the molecule is lower energy and more stable. The coupling of the vibrations of the nuclei and electronic structure results in the breaking of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation which in turn enables symmetry breaking. In Gaussview, symmetry breaking can be allowed by ticking the box in the general section of the calculation window. Only by doing this can conformations be entered hat break the symmetry of the molecule.

The greater conformational freedom in lower symmetry C1 molecule with respect to C2v results in a lower energy conformation being available.

The difference in energy between these symmetries is very low and negligible when compared to the thermal energy available at room temperature (kb x T x NA = 2.478 kJ/mol). Hence inversion of the H atoms on the N atom occur rapidly at room temperature as the activation energy required to reach the higher energy D3h transition state is readily available.

The following higher level calculations were run on the optimsation/MP2/6-311G+(d,p) basis set.

| Point Group | C3v | D3h | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary |

|

| |

| Total Energy (kJ/mol) | -148168.6356 | -148148.1672 | |

| ΔE=E(high energy)-E(low energy)=[(-148148.1672)-(-148168.6356)]= 20.4684 kJ/mol | |||

It should first be noted that direct comparison of energies from the MP2 and DFT calculations can not be done because the basis sets are very different.

The higher level MP2 calculations require more time as more equations must be solved. This hence results in greater accuracy of results with them being only 15.77% different from lit. (24.3 kJ/mol) instead of being a very significant 96.26% off (DFT result). The main difference between the two calculations is that MP2 takes into account the potential energy of electron electron interactions and more importantly the quantum side of this calculation. For instance dynamic correlations between electrons are taken into account by MP2 where as not even static correlations between electrons accounted for by DFT. The DFT method only takes into account coulomb interactions. The difference between DFT and MP2 is 95.55%.

With the more accurate activation energy obtained it can be seen that the thermal energy available is insufficient for inversion of the molecule. However rapid inversion does occur. This is due to quantum tunnelling of the protons from one side of the N atom to the other. H atoms are sufficiently small to experience quantum tunnelling (they are not point charges and have some wave-like characteristics) and hence makes the high activation energy for inversion obsolete.

Vibrational Analysis

The I.R. data was obtained from a frequency/DFT/B3LYP/6-31G basis set.

| Number | Vibrational Form | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry (D3h) | E | 2C3 (z) | 3C2 (y) | σh | 2S3 | 3σv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

-318.051 | 849.113 | A2’’ | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 1 |

| 2 |

|

1640.59 | 55.9828 | E' | 1 | *** | 1 | 1 | *** | 1 |

| 3 |

|

1640.59 | 55.9805 | 1 | *** | -1 | 1 | *** | -1 | |

| Sum | 2 | -1 | 0 | 2 | -1 | 0 | ||||

| 4 |

|

3635.71 | 0 | A1' | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 |

|

3854.27 | 19.5951 | E' | 1 | *** | -1 | 1 | *** | -1 |

| 6 |

|

3854.27 | 19.5963 | 1 | *** | 1 | 1 | *** | 1 | |

| Sum | 2 | -1 | 0 | 2 | -1 | 0 | ||||

| Number | Vibrational Form | Lit. Frequency (cm-1)[17] | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry (C3v) | E | 2C3 (z) | 3σv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

932/968 | 452.299 | 599.472 | A1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 |

|

1626 | 1680.47 | 41.7257 | E | 1 | *** | 1 |

| 3 |

|

1680.47 | 41.7245 | 1 | *** | -1 | ||

| Sum | 2 | -1 | 0 | |||||

| 4 |

|

3337 | 3575.43 | 0.0688 | A1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 |

|

3444 | 3775.76 | 7.0892 | E | 1 | *** | 1 |

| 6 |

|

3775.76 | 7.0885 | 1 | *** | -1 | ||

| Sum | 2 | -1 | 0 | |||||

Irreducible representations were determined as detailed in the BH3 Vibrational Analysis section. All vibration motions for D3h and C3v match as follows -

| D3h No. | C3v No. |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 6 |

| 6 | 5 |

This is to be expected since C3v is a sub group of D3h. The first vibration (no. 1) of both the C3v and D3h are similar to the inversion path taken by NH3. This is further supported by the fact the value for this vibration in the D3h frequencies is negative (-318.051cm-1) - which is an indication of a transition state structure. The inversion path vibration (C3v) is also not very similar in frequency to lit. This is most likely due to the quantum effects mentioned previously (calculation accuracy breaks down at this point).

The rest of the lit. values for the vibrations of the C3v structure are not in very close agreement with the calculated value (approx. 100-400cm-1 difference). This is most likely due the calculation not being of a high enough level (the 10% error stated earlier).

Ansa-Ferrocene Complexes Project

The optimisation of the ferrocene compounds was done by an initial low level Optimisation/DFT/B3LYP/LanL2MB calculation (to enable quicker and more accurate higher level calculations) followed by a higher level LanL2DZ optimisation which applies a pseudo potential and enables d orbitals for the Fe atoms (NB - low lying d orbitals are still not taken into account). This second calculation was run with the additional text pop=full to generate M.O. diagrams. The NBOs were then generated on the Energy/DFT/B3LYP/LanL2DZ basis set with the full NBO option selected.

| Ferrocene[18] | fc[SiMe(flu)][19] | 1,2,3-Trithia[3]ferrocenophane[20] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Ferrocene is a stable staggered complex with a D5d point group. However upon the addition of a bridge between the two ligands the orbital interacts are altered and possible basic character is enabled. This is done by exposing equatorial orbitals and maintaining the rigidity of the ansa structures.

Prior to molecular orbital and NBO analysis, the optimisation accuracy must be checked by comparing the key bond angles and lengths to lit. values.

| Ferrocene | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-C Bond Length (Å) | C-C Bond Length (Å) | C-Fe-C Bond Angle (°) | |||

| Lit.[21] | Calc. | Lit.[21] | Calc. | Calc. | |

| 2.045 | 2.121 | 1.403 | 1.443 | 112.453 | |

The ferrocene optimisation appears to successful with only ~3.5% error in the bond lengths calculated (with respect to the lit.). This value may be a systematic error in the calculation basis set (as it can be seen below it this error margin persists). The angle stated above could not be found in lit. but does enable later comparison (in NBO section) between normal ferrocene ring separation (the two Cp rings appear to be parallel) and the same separation in ansa ferrocenes.

| fc[SiMe(flu)] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-C (to bridge C) Bond Length (Å) | C-C Bond Length (Å) | Si-C (of Cp) Bond Length (Å) | Fe---Si Length (Å) | C-Fe-C (of bridge C atoms)

Bond Angle (°) | |||||

| Lit.[22] | Calc. | Lit.[22] | Calc. | Lit.[22] | Calc. | Lit.[22] | Calc. | Calc. | |

| 2.034 | 2.054 | 1.393 | 1.440 | 1.890 | 1.920 | 2.692 | 2.823 | 85.710 | |

The deviation from lit. of the Fe-C and C-C bonds (1% and 3.5% respectively) is consistent with those obtained for ferrocene indicating the fact the error was caused by the level of calculation. The errors in the Fe---Si and C-Si are gretaer and ~5%. This may be due to the fact that low lying d orbitals are not taken into account by the basis set. This is indicated by the NBO section showing no d orbital character in the Si atom at all. However this error is not too great for the analysis undertaken (M.O. and NBO).

| 1,2,3-Trithia[3]ferrocenophane | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-C (to bridge C) Bond Length (Å) | C-C Bond Length (Å) | S-S Bond Length (Å) | C-S Bond Length (Å) | C-Fe-C Bond (of bridge C atoms) Angle (°) | |||||

| Lit.[23] | Calc. | Lit.[23] | Calc. | Lit.[23] | Calc. | Lit.[23] | Calc. | Calc. | |

| 2.044 | 2.120 | 1.422 | 1.439 | 2.049 | 2.304 | 1.748 | 1.811 | 110.554 | |

The error in all the bond lengths except the S-S bond is approximately 3.5% which is consistent with the trend observed in the other ferrocene compound optimisations. The S-S bond length, however, is significantly higher than the 3.5% error at ~12%. This is most likely due to correlation effects and once again the low lying d orbitals not being taken into account. Thus the analysis of this ansa ferrocene must be taken with caution.

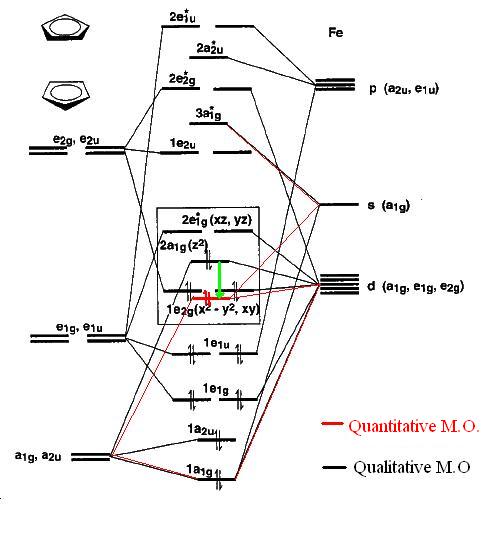

M.O. Diagram Ferrocene

| M.O. Diagram[24] | D5h Symmetry | Qualitative Orbitals [25] | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

e1g |

|

|

| a1g |

| ||

| e2g |

|

| |

| Quantitative Orbitals[18] | ||||

| HOMO-2 | HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 |

|

|

|

|

|

As it can be seen from the above diagram the qualitative and quantitative calculations do not agree on the position of the 2a1g orbital. This is most likely due to the mixing of the Mo 3a1g s orbital with the 2a1g orbital and not the 1a1g (if the basis set level is considered to be sufficiently high to model the M.O.s). This makes sense theoretically because the 2a1g orbital is closer in energy to the unoccupied 3a1g orbital and would hence result in a greater stabilisation of the 2a1g orbital with respect to mixing with the 1a1g orbital (the separation between this orbital and the 3a1g orbital is far larger). To further support this point comparison of the HOMO-2 with the possible outcome of qualitative mixing of the metal s and dz2 orbital shows it corresponds to the lower qualitative orbital (in the diagram). The anti-bonding version in the quantitative M.O. is placed adjacent to this diagram. This orbital does not correspond so well to the qualitative diagram but this is mainly due to the limitations of the Hartree-Fock calculation on unoccupied molecular orbitals.

| Orbital Mixing | Quantitative HOMO-2 | Quantitative Corresponding

Anti-bonding orbital |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Otherwise the molecular orbitals correlate well and shows the fact that around the HOMO and LUMO the molecular orbitals do not have any face of possible attack at the equatorial position. The electron density in the HOMO could act as a lewis base but the position of the Cp rings sterically inhibits this. Hence ansa ferrocenes (Cp rings bridged) could help improve the availability of this electron density enabling greater metal basicity. Lewis acid characteristics of the complex are unlikely due to the electron density being placed in mainly anti-bonding LUMOs. The HOMO itself has some bonding character due to orbital mixing.

It should also be noted that the electron density in the HOMO is also located on the Cp rings (same for all ansa ferrocenes - see NBO section). Hence the Cp rings act as a competing site for electrophiles (the charge is nearly the same on the Cp rings as the Fe - see NBO section below).

Bridging Impacts on M.O. and NBO Analysis

| fc[SiMe(flu)][19] | 1,2,3-Trithia[3]ferrocenophane[20] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO | LUMO | HOMO | LUMO |

|

|

|

|

The HOMOs remain localised on the metal centre. The S3 bridge appears to have little to no impact on the rings. The angle of separation is almost the same as that in the ferrocene. This is because the S3 bridge is very flexible and causes no rigidity in structure. Hence the HOMO orbital is not more exposed at the metal centre - the basic nature of the complex should not be altered greatly. However in the case of the flu complex the ring is significantly strained and pulls the Cp rings together (the C-F-C angle [C atoms are bridging] is lower by ~40°). Thus the HOMO metal orbital is more exposed to increase its basic character. The Si bridge causes greater rigidity and stereochemical control in the molecule.

The LUMO of these complexes seems to imply that nucleophilic attack occurs at the S atoms or the aromatic rings of the flu group. Whilst this appears impossible in theory since both the S atoms and aromatic flu group normally have very high electron density, the bridging the rings appears to reverse this. This is based on the normal bonding orbital calculations run on the molecules.

| Normal Bonding Orbitals (N.B.O.) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ferrocene[26] | fc[SiMe(flu)][27] | 1,2,3-Trithia[3]ferrocenophane[28] |

|

|

|

The S atoms (except the central S atom) are in fact quite electropositive and hence may be susceptible to nucleophilic attack. Bridging appears to have removed electron density from the S atoms linked directly to the Cp rings and transfer it to the S atom at the middle of the bridge. There is no effect on the electron density in the Cp rings and Fe itself in comparison to the ferrocene NBO. Furthermore the d orbitals on the S atom may enable expansion of the octet to enable nucleophilic attack. The reason for the shift in electron density to the central S atom may be due to repulsion of the lone pairs by the aromatic system causing and inductive movement of the electrons towards the point furthest away from the Cp rings - the S atom at the centre of the bridge.

In the case of the flu complex, electron density has been transferred from the more electropositive Si atom to the electronegative C atoms attached (all experience a increased negative charge). The difference between these groups on the Pauling scale is 0.65. Hence with respect to the ferrocene NBO there is greater electron density in the ring itself (especially the bridgehead C atoms). The NBO also indicates the cyclopentane ring C atoms joining the two 6 membered rings together are almost neutral in terms of charge in the molecule. Hence this is a possible site of attack by a nucleophile especially with the LUMO centred on the flu group.

However it should be noted that whilst S atoms highlighted and C atoms in the flu group possibly susceptible to nucleophilic attack, steric and electronic factors must also be taken into account. Hence the large electron density of the S atom in the centre of the bridge and the aromatic ring systems are likely to repel a negatively charged nucleophile from attack in certain geometries. Thus the rate of attack would be very hindered.

All NBOs illustrate that the reactivity of the Cp ring itself is not altered to a significant degree. In the flu complex one of bridgehead C atom is more vulnerable to attack. Otherwise the C atoms are not greatly changed by the bridging.

Conclusion

Computational analysis is a very effective, cheap, time efficient method of analysis at the level of calculations run in the report. However these calculations are based on approximations of integrals etc. to a certain extent. Hence there is inherent errors that can be factored in. Also the accuracy of the optimisation must be treated with caution when lit. values can not be found. This, however, also highlights an important strength of computational methods. Via approximation of lit. values, new and novel compounds properties can be predicted. This for instance enables the influence of bridging on ferrocene to be determined. As reported above unless sterically constricted bridges are used the properties of ferrocene itself. However unexpectedly, for example, the bridge atoms becoming more activated to nucleophilic attack.

References

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1031

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 M. Y. Darensbourg and D. J. Darensbourg, J. Chem. Ed., 1970, 47, 33

- ↑ Simon Sung, DOI:10042/to-1038

- ↑ Simon Sung, DOI:10042/to-1048

- ↑ Simon Sung, DOI:10042/to-1045

- ↑ Simon Sung, DOI:10042/to-1047

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg and R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680-2682 DOI:10.1021/ic50187a062

- ↑ A. D. Allen. and P. F. Barrett, Can. J. Chem., 1968, 46, 1649–1653 DOI:10.1139/v68-276

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 G. Hogarth and T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171 DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 F. A. Cotton, D. J. Darensbourg, S. Klein and B. W. S. Kolthammer, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 2661-2666 DOI:10.1021/ic00137a026

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1033

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1032

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1049

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1034

- ↑ P. Braunstein, J. Taquet, O. Siri, R. Welter, Angew. Chem., 2004, 116, 6048–6051 DOI:10.1002/ange.200461175

- ↑ Y. Du, A. L. Rheingold and E. A. Maatta, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun., 1994, 2163 - 2164 DOI:10.1039/C39940002163

- ↑ D. Dixon and D. A. Dixon, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2005, 109, 5129 DOI:S1089-5639(04)04562-1 10.1021/jp0445627 S1089-5639(04)04562-1

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 DOI:10042/to-1086

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 DOI:10042/to-1085

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 DOI:10042/to-1084

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 J. D. Dunitz, L. E. Orgel and A. Rich, Acta Cryst., 1956, 9, 373-375 DOI:10.1107/S0365110X56001091

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 M. Herberhold, A. Ayazi, W. Milius and B. Wrackmeyer, J. Organomet. Chem., 2002, 656, 71-80 DOI:10.1016/S0022-328X(02)01560-7

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 B. R. Davis and I. Bernal, J. Cryst. Mol. Struct., 1972, 2, 107-114 DOI:10.1007/BF01464791

- ↑ Y. Yamaguchi and C. Kuta, Inorg. Chem., 1999, 38, 4861-4867 DOI:10.1021/ic990173t

- ↑ K. C. Molloy, Group Theory for Chemists: Fundamental Theory and Applications, 2004, Horwood Publishing Ltd., 105-111

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1081

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1082

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1083