Rep:Mod:chchanmod2

Module Two: Bonding (Ab Initio and Density Functional Molecular Orbital) by Chun Ho Chan

Introduction

Simple Main Group Compound - Borane

Optimisation

The first molecule being investigated is a borane, which is a trigonal planar under the D3H point group. The molecule was being input into GaussView and each B-H bond length was set to be 1.5 Å. Via the application of the B3LYP method with the 3-21G basis set, the molecule was optimised to give all H-B-H bond angles at 120o and all B-H bond lengths at 1.19Å. The experimental B-H bond length in BH4- is 1.25Å[1], hence they are in good agreement. The important results summary is shown in Table 1 and the log file for the optimisation can be accessed at Media:BH3_OPTIMISATION_chc08.LOG.

Root mean squared (RMS) gradient is much less than 0.001, which is an indication of the high level of accuracy achieved by this model; whilst the short time taken for the completion of the calculations indicates the simplicity of the model.

|

|

Figures 4 and 5 reflect the optimisation procedure, the position of Hydrogen atoms would continue to be changed until the RMS gradient reaches zero, hence a turning point. Although this indicates a stationary point, but whether it has converged to a minimum or maximum requires further analysis, thus vibrational analysis was performed.

Vibrational Analysis

Table 2 shows the 6 vibration modes which can be performed by the molecule, all the frequencies obtained are positive, hence the optimised energy/structure is at the minimum point of the potential energy curve. The log file is at Media:BH3_FREQUENCY_chc08.LOG.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode | Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1146 | 93 | A2’’ |  |

1205 | 12 | E’ |

|

| 1205 | 12 | E' |  |

2592 | 0 | A1’ |

|

| 2730 | 104 | E’ |  |

2730 | 104 | E’ |

|

|

The A1’ atretch at 2592 cm-1 is infra-red inactive, as it would not cause a dipole moment on the molecule due to its symmetric stretching, hence it would not show on its infra-red spectrum (as shown in Figure 6).

|

|

Molecular Orbital Estimation

|

Molecular orbitals are generated by Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO) theoretically; as shown in Figure 7, the computed molecular orbitals agree with the theoretical approach (The coloured pictures in Figure 7 are the computed results). Based on the energies computed, it has clearly shown that the 1a1' molecular orbital is at a much lower energy level than any other molecular orbitals, which agrees with the theory as it is composed of the 1s orbital of Boron atom, whereas the others are formed by 2s and 2p orbitals of Boron atom with 1s orbitals of Hydrogen atoms. The model can compute most molecular orbital energies accurately, but for 2e' and 3a1', as they have very similar energies with only ~9 kJ mol-1 difference, it is very hard to estimate precisely their arrangement, thus a more accurate model needs to be applied to achieve a better results. As most reactions proceed via HOMO and LUMO interactions, HOMO can be seen clearly as one of two degenerate e' bonding orbitals, whilst the LUMO is the empty non-bonding pz orbital. This explains the Lewis acidity of the molecule as it can accept a lone pair of electrons at the LUMO and this would not have effect on the bond order as it is a non-bonding orbital. For BH3, there is no significant mixing, which can be more important in other molecules. The log file can be accessed at Media:BH3_MO_chc08.LOG

|

|

Natural Bond Orbitals

Natural Bond Orbital is a representation integrating both atomic and molecular orbitals, it shows the nature of bonds and the charge distribution among a molecule. The BH3 molecule is composed with an electron deficient Boron centre, surrounded by electron rich Hydrogen atoms; whilst the charge distribution is calculated as +0.33 at Boron atom and -0.11 at each Hydrogen atom, giving an overall neutral molecule. Figure 8 shows that all the bonds are two centres-two electrons (2c-2e) bond, with 44.48% Boron and 55.52% Hydrogen contributions to the total electron density. The results also show that the Boron centre comprises of 33.33% s-character and 66.67% p-character, whilst each Hydrogen atom has 100% s-character. This implies that Boron uses three sp2 hybridised orbitals for bonding as described with Valance Shell Electron Pair Repulsion(VSEPR) theory. The "lone pair" orbital with 100% p-character centred at Boron indicates the presence of a non-bonding p orbital, which is the LUMO as mentioned previously. In addition, the calculations show there is a 100% s-character orbital at the Boron centre, which is the 1s orbital and it would not interact with other orbitals as it is too low in energy compare to the H3 fragment molecular orbitals.

|

|

Larger Main Group Compound - Thallium Tribromide

Optimisation

|

The same computational model used for BH3 can also applied for TlBr3, since they are both trigonal planar under the D3H point group, but it would be less accurate as there are many more electrons need to be taken into account, thus pseudo potential was applied to give a more accurate optimisation. Psedo potential improves the approximation by including relativistic effects imposed on distant valence electrons. Besides chosing the method and basis set, the point group symmetry was constrained to D3H along with tightening the toleration to 0.0001 to impose strict rules for the convergence; since the RMS gradient is much less than 0.0001, hence the optimisation was successdul and it is of high level of accuracy. The optimisation gives all Tl-Br bond lengths at 2.65Å and all Br-Tl-Br bond angles at 120o. The experimental Tl-Br bond length was measured to be 2.51Å[2], thus the values are still in roughly good agreement, but it can be improved by a more accurate calculation method. The log file can be accessed at Media:TLBR3_OPTIMISATION_chc08.LOG

|

|

|

|

Vibrational Analysis

Table 6 shows the vibrational frequencies computed for TlBr3, all the frequencies are positive values, which confirm the optimised structure is at the minimum point of the potential energy curve. The log file can be accessed at Media:CHC_TLBR3_FREQ.LOG

There is one infra-red inactive mode of vibrations as BH3, the symmetric stretch has zero intensity since it does not generate a dipole moment.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode | Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46 | 4 | E' |  |

46 | 4 | E’ |

|

| 52 | 6 | A2’’ |  |

165 | 0 | A1’ |

|

| 211 | 25 | E’ |  |

211 | 25 | E’ |

|

|

The low frequencies calculated are -3.4213,-0.0026,-0.0004,0.0015,3.9367 and 3.9367 cm-1, which are quite close to zero and their magnitudes are small in comparison with the lowest wavenumber, 46 cm-1; this shows that the method chose was accurate enough for this particular molecule.

|

|

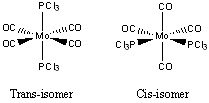

Geometric Isomerism of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Introduction

There are different kinds of isomerism such as linkage isomerism, optical isomerism, and they appear habitually in molecules, especially transition metal complexes; these isomerisms would affect not only the physical and chemical properties of the molecule, but also its spectroscopic properties. In this section, the geometric isomerism of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 would be investigated.

Optimisation

Loose Optimisation

Both isomers were firstly optimised by the B3LYP method with the basis set and pseudo-potential, LANL2MB, which is a low level method, hence loose convergence was imposed to ensure turning points for both structures would be found. The trans-isomer does not possess a dipole moment, which is the same as the BH3 and TlBr3, due to the cancellation of dipole moment in all directions, whereas a dipole moment would be expected in the cis-isomer. This observation is under the assumption of PCl3 acts as an atom, L, hence no P-Cl bond exists. The difference between energies of the two isomers is relatively small, as the energy of cis-isomer is -1.621312 x 106 kJ/mol, whilst for trans-isomer it is -1.621304 x 106 kJ/mol, giving about 8 kJ/mol difference and cis-isomer is thermodynamically slightly more stable. This low energy barrier suggests the possibility of interconversion between the two isomers under this model. Both molecules were computed to have C1 symmetry, which is not true since trans-isomer has higher degree of symmetry.

|

|

|

The RMS gradients for both optimisations are very small, which indicate stationary points were being found, but these can be fake minimums as there might be more than one turning points on the potential energy curves of the molecules as suggested in Figure 15. Based on this possibility and the fail of assigning symmetry of this model, a tighter optimisation is required in order to improve the results.

|

|

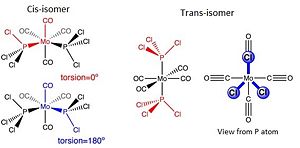

Tight Optimisation

|

To perform a tighter optimisation, the same B3LYP method was applied but with LANL2DZ pseudo-potential and basis sets, also the electronic convergence was increased. In addition, the torsion angles were modified according to Figure 16 before the calculations.

|

|

|

|

Geometric Parameters and Theoretical Prediction of Stability

As seen in Table 12, all the bond lengths and bond angles are in good agreement with the literature values, since the exact compounds could not be found, thus similar molecules were used. The cis-isomer literature values were based on cis-Mo(CO)4(PMe2Ph), whilst trans-Mo(CO)4PPh3 was used for comparison.

| Cis-isomer | Cis-isomer Literature[3] | Trans-isomer | Trans-isomer Literature[4] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-P Bond Length /Å | 2.51 | 2.53 | 2.48 | 2.50 |

| Mo-C Bond Length /Å | 2.01 and 2.06 | 1.98 and 2.02 | 2.11 | 2.01 |

| P-Mo-P Bond Angle /o | 94.2 | 94.8 | 180 | 180 |

| P-Mo-C Bond Angle /o | 89, 92 and 176 | 88, 94 and 176 | 89 and 91 | 87 and 92 |

| C-Mo-C Bond Angle /o | 87, 89, 90 and 178 | 88, 90, 93 and 177 | 90 and 180 | 92 and 180 |

As PCl3 is a medium group, therefore some steric effects would be expected in the cis-isomer, which would destabilise the isomer. Although steric effects is important, but electronic effects also need to be considered. For the cis-isomer, a trans-effect is present between the P atom and CO group to stabilise the molecule; the non-bonding orbital at P can interact with the π* orbital of CO to form two new molecular orbitals to enhance stabilisation. Thus it is hard to predict whether steric effects or electronic effects would affect the molecule stronger.

By changing the substituents around P atom, the stability of geometric isomers can be altered. To achieve a more stable trans-isomer, a very bulky group such as PPh3 can be used as substituent to maximise the steric effects; Alternatively, if a cis-isomer is more stable, it would have small and electron-donating substituent, such as CH3, to minimise the steric effects and maximise the electronic effects.

Vibrational Analysis

Minimum Stationary Point Justification

To further confirm the stationary points found during the optimisations are at their minimums, vibrational analyses were carried out. All the vibrational frequencies calculated are positive illustrating the optimised structures are at the minimum stationary points of their respective potential energy curves. The log files of cis- and trans-isomer frequency calculations can be accessed at Media:Cis_frequency_chc08.out and Media:Trans_frequency_chc08.out respectively.

|

|

The low frequencies of cis-isomer are -1.9993, -0.0003, 0.0004, 0.0005, 0.8168 and 1.2763 cm-1, whilst for trans-isomer, they are -2.1478, -1.5103, 0.0004, 0.0005, 0.0005 and 3.4585 cm-1. All these are very close to zero, which indicates it is an acceptable method to compute these compounds.

Vibrations at Low Energies

On the computed infra-red spectra as shown in Figure 17 and 18, there are peaks at very low wavenumbers; these are corresponded to the weak Mo-P bond stretches, and they would general happen at room temperature (normally less than 207 cm-1. This is one of the reasons why GaussView failed to predict the correct point group of the molecules, as the P groups can rotate freely around the Mo metal centre.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode | Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 0.03 | A |  |

18 | 0.01 | A |

|

| 42 | 0.00 | A |  |

44 | 0.10 | A |

|

| 56 | 0.83 | A |  |

67 | 0.22 | A |

|

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode | Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.09 | A |  |

6 | 0.00 | A |

|

| 37 | 0.42 | A |  |

40 | 0.31 | A |

|

| 72 | 0.00 | A |  |

79 | 1.07 | A |

|

|

|

Carbonyl Stretches

Symmetry of a molecule would affect its spectroscopic data, therefore infra-red spectroscopy can act as a tool to identify geometric isomers like Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2. The computed frequencies are illustrated in Table 17 and 18.

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode | Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 | 762 | A |  |

1949 | 1500 | A |

|

| 1959 | 634 | A |  |

2024 | 597 | A |

|

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode | Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry | Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 1475 | A |  |

1951 | 1467 | A |

|

| 1977 | 1 | A |  |

2031 | 4 | A |

|

|

The computed results clearly differ from the literature values, which can be explained by the wrong symmetries of the computational models. The point group of the cis-isomer is C2V, whereas the trans-isomer is under the D4H point group. As the trans-isomer is of a high degree of symmetry, therefore there would be fewer different carbonyl stretches expected, which agrees with the literature (experimental) values. Since the computational model assigned the symmetry to be C1 (the lowest symmetry point group), therefore four different vibrational modes were computed. For the cis-isomer, as it has a lower level of symmetry, thus a few different carbonyl stretches would be expected, which again agrees with the literature values. The computational model correctly predicted 4 different stretches, but the symmetry and wavenumber of each stretch are different from the literature values. The computed stretches should have the following symmetries, 1950 cm-1 of B2, 1951 cm-1 of B1 and both 1977 and 2031 cm-1 are of A1. Alteration of the point group during optimisation can help to improve not only the optimisation results, but also the vibrational frequency estimations. |

|

||||||||||||||||||

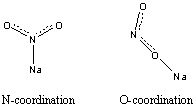

Mini Project - Structure of Sodium Nitrite (NaNO2)

Introduction

As mentioned above, isomerisms present in numerous molecules; even for a very small system like NaNO2, linkage isomerism can occur. In this molecule, Nitrogen atom and Oxygen atoms can coordinate with the positively charged Na+ ion, which leads to two possible structures of the molecule. In this section, the structures would be optimised and their relative energies would be compared to predict the more stable structure.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 19 - Ground State Theoretical Structures of NaNO2. |

|

Optimisation

To compute the two structures, B3LYP method with 6-311G(d) basis set was used, which took into account all the electrons. Based on the first optimised results, different point group constraints were applied with tight toleration to determine the best optimised structure.

N-coordinated NaNO2

|

|

|

|

Based upon the 4 optimisation summaries, all 4 structures have very similar energies and dipole moments. Although N-coordinated NaNO2 is not under a highly symmetrical point group, but it still has a certain level of symmetry; therefore by increasing its symmetry from C1 to C2V, the RMS gradient would decrease giving a better optimisation towards the stationary point of the potential energy curve. The bond lengths obtained from the optimisation are 1.24 Å for N-O bond and 2.20 Å for Na-N bond. The N-O bond length agrees with the literature value, 1.24 Å[6], hence this model is relatively accurate for the NO2- structure. Both C1 and C2 constraints did not work for the molecule, as they were being forced into CS and C2V respectively.

O-coordinated NaNO2

The energies optimised are very similar but the RMS gradient shows that optimisation 6 is closer to the stationary point of potential energy curve of the structure, which is due to the tight toleration since the symmetry of the structure was being forced to be CS. N-O bond length was computed to be 1.26 Å and Na-O bond length was optimised to be 2.22 Å; the N-O bond length agrees with the literature value as mention above, which is 1.24 Å.

|

|

The log files for the optimisations can be accessed at

|

Optimisation 1:Media:NANO2_OPTIMISATION_chc08.LOG, |

Optimisation 2:Media:NANO2_OPTIMISATION_C1_SYMMETRY_chc08.LOG, |

|

Optimisation 3:Media:NANO2_OPTIMISATION_C2_SYMMETRY_chc08.LOG, |

Optimisation 4:Media:NANO2_OPTIMISATION_C2V_SYMMETRY_chc08.LOG, |

|

Optimisation 5:Media:NAONO_OPTIMISATION_chc08.LOG and |

Optimisation 6:Media:NAONO_OPTIMISATION_C1_SYMMETRY_3_chc08.LOG |

Vibrational Analysis

Vibrational frequencies are estimated to further determine which optimisation structure is the most optimised one; also, vibrational frequencies are used to confirm if the stationary point found by optimisation is the minima.

N-coordinated NaNO2

|

|

|

|

Although the low frequencies are not in the acceptable range, hence the method is not the best computational model for this structure, this can be explained by the very ionic nature of Na-N bond. For each optimised structure, there is one mode of vibration which has a negative frequency; this indicates all these structures are at a maximum stationary point, and so they are all transition state of the energy curve. Based upon optimisation results and vibrational frequencies, optimisation 4 is the best transition state structure.

O-coordinated NaNO2

|

|

The low frequencies for both optimised structures are roughly in the acceptable range, therefore a better computational model should be used for this structure. All vibrational frequencies obtained are positive, which provide evidence these structures are at a minimum stationary point of the energy curve. Based upon optimisation results and vibrational frequencies, optimisation 5 is a better optimised structure.

The log files for the vibrational frequency calculations can be accessed at

|

Optimisation 1:Media:NANO2_FREQUENCY_chc08.LOG, |

Optimisation 2:Media:NANO2_FREQUENCY_C1_SYMMETRY_chc08.LOG, |

|

Optimisation 3:Media:NANO2_FREQUENCY_C2_SYMMETRY_chc08.LOG, |

Optimisation 4:Media:NANO2_FREQUENCYC_C2V_SYMMETRY_chc08.LOG, |

|

Optimisation 5:Media:NAONO_FREQUENCY_chc08.LOG and |

Optimisation 6:Media:NAONO_FREQUENCY_C1_SYMMETRY_3_chc08.LOG |

Conclusion

Theoretically based upon the two optimised structures, O-coordination would be predicted to be more stable as it has two oxygen atoms donating electron density towards the Na+, whereas N-coordination only has one coordination and the negative charge of the anion is delocalised among all three atoms making N less electron rich. The computational model estimate the N-coordination is the transition state whilst the O-coordination is the ground state, this suggests that when the anion is rotating, it would rotate from the O-coordination state to the N-coordination state, and then return to O-coordination state. The method used for the project is B3LYP, which is a low level calculation method; to improve the results, a higher level method can be applied, but it would increase the time consumption. For such ionic compound, molecular orbital may not be the best approach to analyse stability as it depends more on the Coulombic interactions between the opposite charged species than the orbital overlap.

Reference

- ↑ L. Radom, Aust. J. Chem., 1976, 29, 1635-40

- ↑ J. Glaser and G. Johansson, Acta. Chem. Scand. A., 1982, 36, 126

- ↑ F. A. Cotton, D. J. Darensbourg, S. Klein and B. W. S. Kolthammer, Inorganic Chemistry, 1982, 21, 294-299

- ↑ G. Hogarth and T. Norman, lnorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171

- ↑ F. A. Cotton, Inorganic Chemistry, 1964, 3, 702-711

- ↑ L. Radom, Aust. J. Chem., 1976, 29, 1635-40