Rep:Mod:certiorari2

Third Year Computational Chemistry Lab, by Simon Krautwald

Module 2 - Bonding (Ab Initio and Density Functional Molecular Orbital)

The following exercises will use computational methods based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) to investigate selected molecules and phenomena in inorganic chemistry. In order to develop a better understanding of these, molecular orbitals and vibrational spectra will be visualized and evaluated in the discussion. The use of pseudopotentials for computing the properties of metal complexes will be introduced. The module will conclude with a short miniproject on the properties of carbenes and other group 14 analogues thereof, mainly the germylenes. If at any time it appears that the focus lies heavily on the organic carbenes, this is because they are as yet the overwhelmingly important species in metal-carbene complexes and a thorough understanding of these ligands is necessary before addressing the heavier analogues.

BH3, BCl3 and SO2

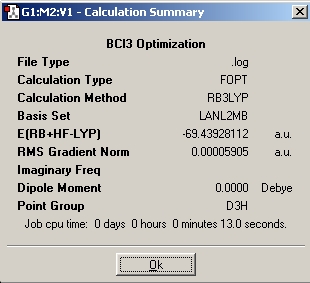

The image to the side is the summary of the computation carried out by Gaussian. The point group is D3h, this is the correct and same result one obtains when one derives the point group by hand. The dipole moment is zero, this also passes the sanity check. The molecule has high symmetry and all the B-Cl bonds are equivalent, so there is no net dipole. Moreover, the calculation method B3LYP and basis set/pseudopotential (LANL2MB) are shown. The computation took only 13 seconds.

After the optimization of the BCl3 molecule, the following values are obtained using the Inquire button:

d(B-Cl)=1.86592 Angstroms

Angle(Cl-B-Cl) = 120 degrees

In analogy to what was done for BCl3, this image shows the calculation summary for SO2. The point group is C2v, this is correct and follows our expectations. The molecule has the same geometry and symmetry elements as water, which is an elementary exercise in assigning point groups. SO2 has a dipole moment, again, like water, because the bent arrangement of atoms means that the two S-O bond dipoles do not cancel; in fact, they give rise to a net dipole.

d(S-O): 1.58232 Angstroms

Angle(O-S-O): 114.355 degrees

It will be interesting to see how well these predicted values agree with the literature, in order to get a feel for the kind of accuracy that can be expected from such a fast computation.

The optimized and final atomic coordinates of the three atoms (obtained from the log file) are as follows:

Sulfur: x = 0.000000, y = 0.000000, z = 0.428839

Oxygen: x = 0.000000, y = 1.329712, z = -0.428839

Oxygen: x = 0.000000, y = -1.329712, z = -0.428839

It can thus be seen that a) the molecule is flat (all x = 0), and that the two oxygen atoms are exactly the same distance from the sulfur atom. These are obvious points, but it is nice to see them reproduced in the output file.

Vibrational Analysis of BH3

The predicted vibrational spectrum of BH3 is presented below. There are only three lines, whereas the molecule has six vibrational modes. In IR spectroscopy, only so-called IR-active modes are observed. These are vibrations that lead to a change in dipole moment of the molecule. Vibration 4, being totally symmetric, does not lead to a change in dipole moment and thus has a predicted and observed intensity of zero. Of the five remaining modes, four belong to two pairs of degenerate vibrations (same energy). These absorptions will hence overlap in the spectrum and only one signal will be seen, although two modes are being excited when light of the correct energy is absorbed.

Molecular Orbitals of BH3

The molecular orbitals of the BH3 molecule were calculated along with the vibrations. The table below shows the surfaces computed by Gaussian. Without exception they look very similar to what qualitative MO theory would predict them to look like. Qualitative MO theory obviously cannot predict every little twist and turn of the surface, but the general shape of the orbitals and, crucially, the relative sizes of the coefficients, agree well. This is particularly well illustrated by MO 6, an antibonding orbital of e' symmetry. The overlap is out-of-phase, and where the wavefunctions cancel a node can be seen. Furthermore, the p-orbital component has larger, more diffuse lobes than the two 1s components coming from hydrogen.

This is quite a pleasing result, because it says that for simple enough molecules, qualitative MO theory can give good results very fast. The following would be interesting to investigate: When a Lewis base coordinates to BH3, it donates electron density into the LUMO, i.e. the empty p-orbital on boron. When this happens, the symmetry of the molecule changes and the former p-orbital is now able to mix with ... as they have the same symmetry. This mixing creates an occupied orbital of lower energy so that the total energy of the molecule goes down. This lowering in energy due to mixing accounts for BH3's properties as a potent Lewis acid. It would be interesting to see how well (compared to a computation) qualitative MO theory can predict the shapes of mixed orbitals, since the fragment orbitals for mixing are somewhat more complex. Unfortunately, I did not have the time to complete this.

Another helpful feature of the qualitative approach is that one can visualize facts easily merely by thinking about the symmetry and rough arguments about bonding or antibonding overlap. This gives the process a certain transparency. A computation in Gaussian, on the other hand, is quite opaque, and it is easy to simply take the result without thinking about what it means or where it comes from.

An Organometallic Complex

In the following exercise the geometry of cis- and trans-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 will be optimized using DFT methods, followed by computations that produce the vibrational spectra of both compounds from the optimized structures. There are two very interesting aspects to this work - "Which isomer is thermodynamically more stable, and why?" and "What do the vibrational spectra tell us about the molecule in terms of symmetry/ structure, and do they agree with experimentally obtained spectra?". The reliability of the geometry optimizations will be checked by comparing relevant bond lengths and associated bond angles to values found in the primary literature.

The molybdenum complexes are zero valent, i.e. the oxidation state of Mo is zero (there are only so-called L-type ligands). 6 L-type ligands provide 12 electrons, another six come from the d6 Mo. Thus, we are dealing with 18 electron complexes.

The four optimization jobs (cis, cis with d-function, trans, trans with d-functions) were submitted to the SCAN and the results put in the digital repository. The unique identifiers for the geometry optimizations are as follows:

cis: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1189

cis with d-functions: Unable to publish to D-Space

trans: Unable to publish to D-Space

trans with d-functions: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1190

Note: The above links refer to the second optimizations, respectively, i.e. the one using strict convergence criteria and the better LANL2DZ basis set.

| Complex | d(Mo-P)/A | d(P-C)/A | d(Mo-C) trans to Mo-P/A | d(Mo-C) cis to Mo-P/A | d(C-O) trans to Mo-P/A | d(C-O) cis to Mo-P/A | Angle (P-Mo-P) | Angle(P-Mo-C) | Angle (C-P-C) in PMe3 | Angle(C-Mo-C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 | 2.6479 | 1.89 | 1.9820 | 2.0326 | 1.1916 | 1.188 | 92.92 | 177.7 | 101 | 178 |

| trans-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 | 2.5717 | 1.89 | - | 2.0285 | - | 1.1898 | 179.97 | 89-91 | 101 | 179.99 |

| cis-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 with d-functions | 2.58917 | 1.85309 | 1.99361 | 2.03201 | 1.19026 | 1.18805 | 94.007 | 176.887 | 101.560 | 176.873 |

| trans-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 with d-functions | 2.525 | 1.848 | - | 2.03 | - | 1.189 | 179.33 | 89-91 | 101 | 179.6 |

A brief look at the above table is instructive. Both the cis and the trans complexes are predicted to have an almost perfect octahedral coordination environment, as indicated by the angles of ~90 and ~180 degrees. The small deviations are either due to the Gaussian programme not quite recognizing the symmetry of the complexes or, more likely, due to the steric bulk of the three methyl groups on the phosphine ligands. The C-P-C angle in the PMe3 ligands is 101 degrees, suggesting a slightly distorted tetrahedral geometry around phosphorus.

In the cis complex, the Mo-P bond is 0.07 A longer than in the trans isomer. This could have two reasons. First, in the cis complex the slightly bulky methyl groups on adjacent phosphorus atoms clash and therefore a shorter Mo-P bond will quickly destabilize this geometry. Second, in the cis isomer the phosphine ligands are trans to the very good Pi-acceptor CO ligand, which will make the metal less able to backdonate electron density into the Mo-P bond orbital and thus weaken/lengthen the bond. However, this argument cannot actually be applied to the computations of cis and trans that don't invoke d-orbitals on phosphorus, i.e. it can only be applied to rows 3 and 4 (with d-functions) in the table.

In the trans isomer, the Mo-C bond to the carbon atom of the carbonyl ligand has the same length as in the cis isomer (2.03 A). In the cis isomer, however, the two Mo-C bond lengths differ in that the Mo-C bonds to carbonyls that are trans to phosphine ligands are 4 picometres shorter than when the carbonyls are trans to another carbonyl ligand. This can be understood by considering the Pi-accepting capacities of the two ligands. CO is virtually the best Pi acceptor and somewhat better than phosphine ligands. Thus, when a CO ligand is trans to a phosphine, it competes for backdonation from the metal with a weaker Pi acceptor (phosphine) rather than one of equal strength (a CO). This means it will be able to accept a little more electron density from the metal and thus strengthen/shorten the Mo-C bond.

Including the d-functions in the calculations clearly has a notable effect. The Mo-P bond distances become shorter by about 7 pm. This agrees with our expectations. Gaussian can now include overlap of filled metal d-orbitals with empty p-orbitals on P of appropriate symmetry and thus the Mo atom backbonds to P, resulting in a strengthening and thus shortening of the Mo-P bond. The P-C distance in the PMe3 groups is also shortened by about 4 pm, indicating that there is some contribution to the P-C bond from the d-orbitals on phosphorus.

Alyea et al. deduced the crystal structure of trans-Mo(CO)4(PCy3)21. Although this is not identical with the compound at hand, it can be expected to have very similar geometrical parameters because the substituents on P are also aliphatic, i.e. electronically very similar. Some bond angles will differ, however, due to the larger steric bulk of the PCy3 group. Watson et al. deduced the structure of the cis isomer of the above compound2, and these values will be used as reference for our cis complex with PMe3 ligands.

Elmers values for their trans complex are as follows:

d(Mo-P) = 2.5436(9) A

d(Mo-C) = 2.020(4) A

d(Mo-C) = 2.028(3) A

d(P-C) = 1.872(3) A

Angle (C-P-C) = 101 degrees

The values in the above table in rows 2 and 4 (w/ and w/o d-functions) both agree very well with the literature, in fact, they are 2.57/2.52 and 2.03. The P-C bond lengths also only differ by about 2 picometres. The C-P-C angle agrees with ours of 101 degrees. This suggests that the geometry optimization was succesful.

The values of the corresponding cis-PCy3 complex are:

d(Mo-P) = 2.654(4) A

d(Mo-C) = 2.020(4) A

d(Mo-C) = 2.028(3) A

The values for the cis complex also agree very well. The geometry optimization can thus be trusted.

The images presented in the table above are the calculation summaries for each of the four geometry optimizations and frequency calculations carried out. They are labelled accordingly. For the calculations without d-functions, the energies of the cis and trans complexes differ by 0.00284619 atomic units (Hartrees), which corresponds to 7.47 kJ/mol. In fact, the cis isomer is the more stable isomer (it has a more negative energy). This initially strikes one as odd, since the trans complex has the two bulky phosphines arranged far away from one another. Since the trans complex is sterically clearly the more favourable arrangement, there must be some electronic factor at work which stabilizes the cis isomer. The cis-complex has a dipole moment, that of the trans isomer is virtually zero (ideally it should be, the fact that it is not suggests that Gaussian doesn't get it quite right). The same goes for the point groups. The trans isomer ideally has D4h symmetry.

It was shown experimentally that for certain complexes that the trans isomer is actually more stable. The most straightforward way to force a trans geometry is to use as bulky a phosphine ligand as possible, but even with some bulky substituents such as OtBu3 the cis isomer is more stable and observed experimentally, so this does not work always. A way of quantifying a ligand's steric bulk is to look at its cone angle.

The frequency calculations were submitted to the SCAN as well and published in DSpace. Their unique identifiers are as follows:

cis freq: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1304

cis with d-functions freq: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1302

trans freq: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1191

trans with d-functions freq: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1303

| Complex | v(CO)/ cm-1 | Intensity | v(CO)/ cm-1 | Intensity | v(CO)/ cm-1 | Intensity | v(CO)/ cm-1 | Intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 | 1849.33 | 1094.23 | 1850.46 | 1947.54 | 1869.97 | 652.915 | 1960.33 | 336.543 | |

| trans-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 | 1838.43 | 1999.6 | 1838.74 | 2007.14 | 1882.17 | 0.0005 | 1953.96 | 0.0001 | |

| cis-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 with d-functions | 1851.04 | 1953.59 | 1856.44 | 1048.29 | 1873.78 | 665.846 | 1959.91 | 368.906 | |

| trans-Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2 with d-functions | 1843.67 | 1979.16 | 1843.89 | 1988.8 | 1884.63 | 0.6514 | 1956.18 | 0.2108 |

The results qualitatively agree with the experimental ones. Only one signal is seen for the trans compound, arising from two degenerate vibrational modes. The other two modes have zero intensity as the vibration does not result in a change in dipole moment. For the cis compound, four vibrations are observed, each with high intensity as they give rise to a large change in dipole moment.

Darensbourg found the following results for the cis complex (his ligand was PPh3)3:

2023, 1927, 1908, 1897 cm-1 in tetrachloroethylene solution

The computations give systematically lower stretching frequencies. This is probably due to approximations made in method and basis set. The experimental result for the trans PPh3 complex (spectrum recorded by myself in 2nd year lab) was 1893 cm-1. Again, this is about 50 cm-1 higher than the computed result presented in the table above.

-8.672 cm-1 and -3.0788 cm-1 for trans, -7.2593 cm-1 for cis.

There was an additional interesting observation worth mentioning. The frequency calculation for the cis isomer and for the trans isomer with d-functions gave one and two negative stretching frequencies, respectively. This is a little odd. Normally a negative frequency indicates that the calculation has not, in fact, obtained a minimum on the PES, but rather a maximum, i.e. a transition state. But the total energy of both complexes is very similar to that of the other complexes (without negative frequencies), so this suggests that Gaussian has actually managed to get very close to the minimum. This begs the question: What kind of transition state are we dealing with here?

A clue to the answer to this question is obtained by animating the negative vibrations in question in GaussView. Looking down the P-Mo-P axis in the trans complex, the motion looks like the two PMe3 groups are trying to rotate about this axis. Rotations about single bonds in general give rise to different conformations of the same molecule, much like in well-known examples ethane (staggered-eclipsed) or butane. This suggests, then, that Gaussian has actually optimized the geometry to one that is not the lowest energy conformation, but rather one in which the two PMe3 groups are in the middle of changing from one conformation to another. This is also the reason why the frequency is negative - Gaussian has optimized to a very small local maximum which is the TS of conformational change, and any departure (vibration) from this geometry will result in a lower energy conformation. The absolute values of the frequencies are small and not more negative than about -8 cm-1. This is because the barrier to rotation (i.e. the barrier to conformational change) is rather small. In ethane, it is large, because the two methyl groups are directly connected and and eclipsed conformation is really very unfavourable. In the molybdenum complex, it is fairly small because the two PMe3 groups are quite far apart (two times the Mo-P bond length, about 5 A), so an eclipsed arrangement does not cause as much steric clash as in ethane. Furthermore, the four rod-shaped carbonyl ligands do not interfere with the phosphine ligands and thus make rotation easier. It would be interesting to convert these energy values to kJ/mol and compare to the thermal energy available at room temperature. Maybe the rotation occurs many times a second at room temperature?

References

1. Elmer C. Alyea; George Ferguson and Shanmugaperumal Kannan; Acta Cryst., 1996, C52, 765-767. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1107/S010827019600100X

2. Watson, M., Woodward, S., Conole, G., Kessler, M. & Sykara, G.; Polyhedron, 1994, 13, 2455-2458

3. D. J. Darensbourg and R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680

Ammonia

Symmetry

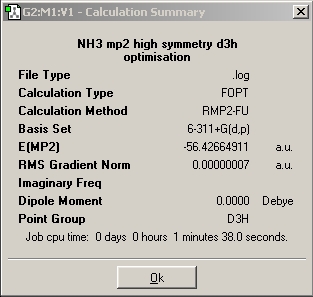

In this section, the small ammonia molecule was investigated, and specifically the impact of point group symmetry on the final structure, energy and time required for computation.

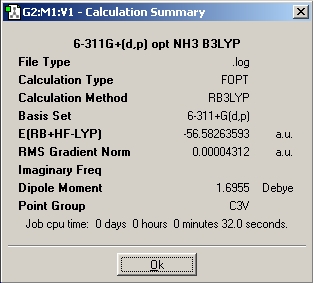

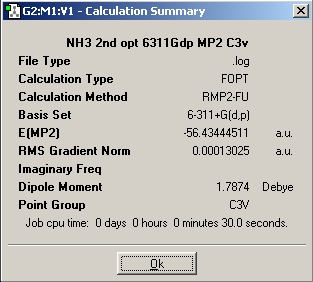

Using a 6-31G basis set, the optimized bond length is 1.00591 A/ 1.00595 A and the H-N-H angle is 116.251/ 116.158, respectively, for the computation with and without symmetry. Also, when the symmetry is ignored, the three H-N-H angles are very slightly different. Images of the calculation summaries are included in the table above (last two pictures). As outlined in the instructions, the high symmetry computation assigns C3v symmetry, whereas the one that ignores symmetry assigns the C1 point group to ammonia. The C3v calculation completed significantly faster than the C1 calculation (27 sec vs 44 sec). The D3h calculation took one minute and 17 seconds, much longer than the other two. It is interesting to note that the lowest energy structure of the three is the C1 molecule with no symmetry! The energy differences between the three molecules in atomic units an kJ/mol are as follows:

E(C3v-C1) = 0.00000172 a.u. = 0.004515860344 kJ/mol

E(D3h-C1) = 0.00034573 a.u. = 0.90771418415 kJ/mol

E(D3h-C3v) = 0.00034401 a.u. = 0.9031983238 kJ/mol

Thus the difference between C3v and C1 isn't large, but it is there. The fact that the D3h molecule is still D3h after the optimization suggests that Gaussian does not allow symmetry breaking during the optimization. The advantage of defining a symmetry for one's molecule is that it speeds up the computation, it effectively constrains the programme in what it can and cannot do during the optimization. This is useful when e.g. the crystal structure of a compound is known to have a certain symmetry and computations are supposed to be carried out on that symmetry. The disadvantage is, of course, that other minima with different symmetries might simply be missed, as is the case for D3h.

The energy difference between C3v and D3h is about 0.9 kJ/mol. This is not very much, and it gives you an idea of the energy of the transition state of inversion relative to the ground state molecule.

Why did the optimization of the D3h structure take so much longer? Probably because the file was specially prepared and contained a dummy atom, which increases the number of computations necessary and thus the time it takes to complete.

Methods

E(D3h-C3v B3LYP) = 0.15598682 a.u. = 409.54 kJ/mol

E(D3h-C3v MP2) = 0.00779600 a.u. = 20.47 kJ/mol

E(C3v B3LYP-C3v MP2) = 0.14819082 a.u. = 389.08 kJ/mol

The more stable ammonia molecule is the one resulting from the B3LYP calculation. Whether this is accurate, however, is in question. The difference between the energy of B3LYP and the TS is 409.54 kJ/mol. This is a very high barrier, and if this result was correct then nitrogen atoms in molecules would probably be chiral centres since the lone pair would then not be able to invert its position. The MP2 result makes much more sense, because it leads to a barrier of 20.47 kJ/mol, which is in rough agreement with the literature value of 24.3 kJ/mol. It is quite impressive, that a laptop calculation taking only minutes can achieve this. In this argument, we rely of course on the accuracy of the energy of the transition state. Thus, delta E has changed massively in going from the B3LYP/6-31G to the MP2/6-311+G(d,p) sets, from 0.9 to 20.47 kJ/mol.

Impressively, the computations only take a little longer to complete. It was 27 sec for B3LYP/6-31G, and only 30 sec for MP2 for the C3v molecule. The D3h took 1 minute and 38 sec instead of 1 minute 17 sec (1.27 times as long). In conclusion, the use of a better method and basis set slightly increased the computational expense and massively increased agreement with experimental values. Pretty good value for money.

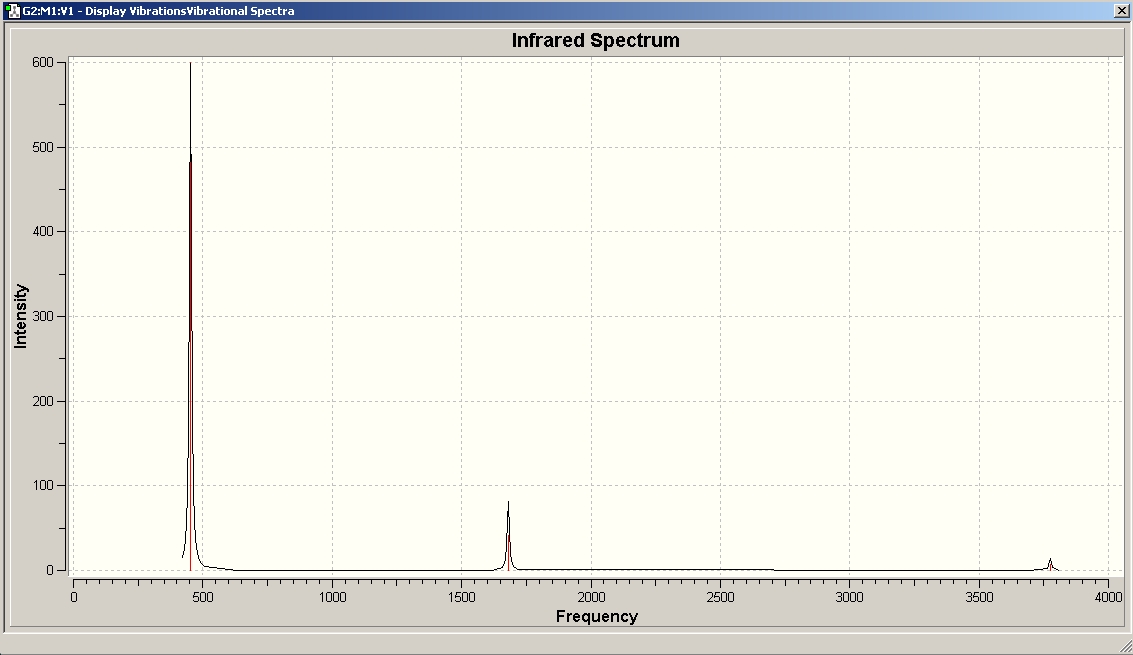

Vibrational Spectrum of NH3

This section will deal with the vibrational spectrum of ammonia. The table below shows pictures taken of the vibrations along with descriptions of the atomic motion. It will help to refer back to the table at the start of the wiki, where the vibrations of BH3 are presented, because they are extremely similar if not identical. No. 1 is the vibration following the inversion reaction path.

| No. | Form of the Vibration | Frequency/ cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3H vibrating symmetrically up and down out of the xy plane. When they move up, the N atom moves down a bit, and vice versa. H and N atoms are moving in z direction only. Corresponds to vibration 1 of BH3. Also, this is the vibration which follows the inversion reaction path | 452.302 | 599.472 | A1 |

| 2 | Symmetric inwards and outwards bending of two N-H bonds, while the remaining N-H bond (along y-axis) moves up and down out of the xy plane. The one H atom is displaced most from the xy plane when the other two H atoms are closest together. Similar to vibration 2 for BH3 | 1680.47 | 41.7256 | E |

| 3 | essentially the same displacement vectors as no. 3 for BH3, see table at start of wiki | 1680.47 | 41.7245 | E |

| 4 | essentially the same displacement vectors as no. 4 for BH3, see table at start of wiki | 3575.43 | 0.0688 | A1 |

| 5 | essentially the same displacement vectors as no. 6 for BH3, see table at start of wiki | 3775.76 | 7.0892 | E |

| 6 | essentially the same displacement vectors as no. 5 for BH3, see table at start of wiki | 3775.76 | 7.0884 | E |

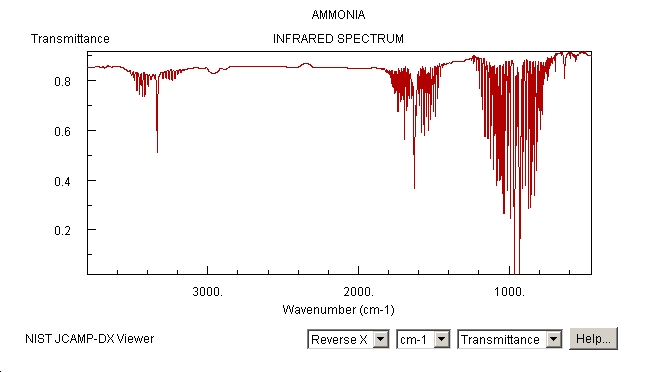

This pictures shows the predicted IR spectrum of C3v NH3.

We can compare this predicted IR spectrum with the one recorded in the gas phase by Dow Chemical Company, which is available via NIST:

http://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C7664417&Units=SI&Type=IR-SPEC&Index=1#IR-SPEC

The stretch at around 1500-1680 is present, as well as the one above 3000, although above 3000 the discrepancy is quite large. The many signals at around 1000 in the experimental spectrum are missing in the predicted spectrum, and vice versa, the predicted signal at 452 cannot be observed in the experiment. There are many more signals in the experimental spectrum because it has been recorded in the gas phase - therefore, the rotational fine structure can be seen! Gaussian does not predict this.

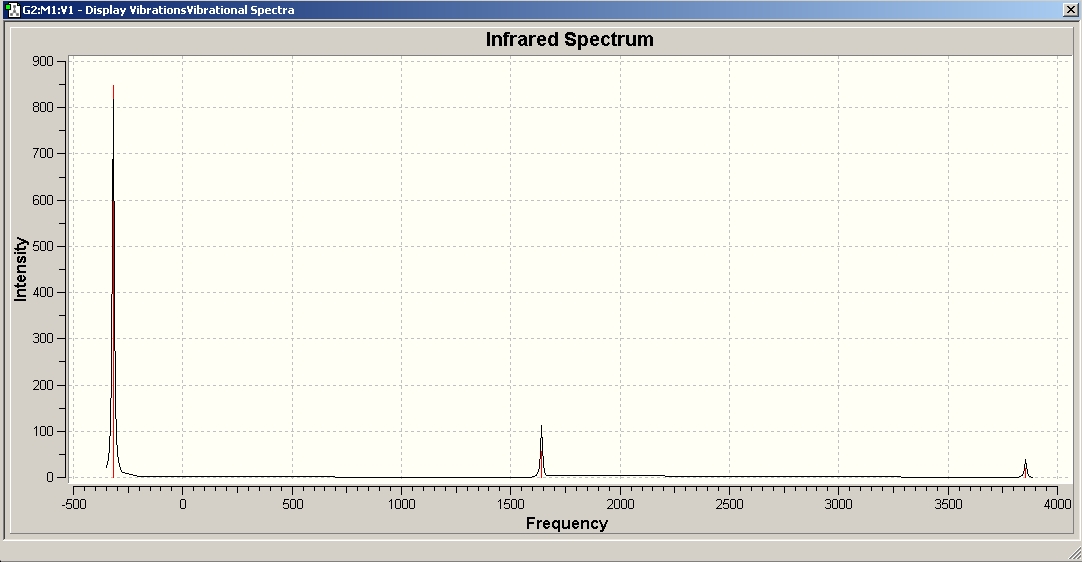

The following table shows the vibrational modes and frequencies of the transition state of the inversion process, and the image shows the predicted IR spectrum.

| No. | Form of the Vibration | Frequency/ cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Negative vibration which corresponds to molecule moving away from the transition state. This can clearly be seen animating the vibration - we observe the inversion process which is shown diagramatically on the instruction website | -318.051 | 849.113 | A2 |

| 2 | see no.2 in table for BH3 | 1640.59 | 55.9828 | E' |

| 3 | see no.3 in table for BH3 | 1640.59 | 55.9805 | E' |

| 4 | see no.4 in table for BH3 | 3635.71 | 0 | A1' |

| 5 | see no.5 in table for BH3 | 3854.27 | 19.5951 | E' |

| 6 | see no.6 in table for BH3 | 3854.27 | 19.5963 | E' |

Miniproject - Carbenes and Germylenes

In this short project the geometry of selected carbenes and germylenes will be optimized using DFT methods. The resulting output from the Gaussian calculations will be used to analyze the electronic structure, predicted vibrational frequencies and geometric parameters of the molecules to get a better picture of the bonding situation in these molecules. Furthermore, it will be instructive to see how well the computed properties of the molecules agree with the experimentally recorded ones. The study of the electronic structure of N-heterocyclic carbenes is interesting as they have found use as ligands in transition metal catalysis (e.g. Grubbs alkene metathesis) and from a theoretical point of view because the bonding they exhibit is unusual.

As a preliminary expedition into computational carbene chemistry, the structures of CH2: (singlet and triplet) were optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G level including a full natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis. The optimized geometries had bond angles that agreed very well with experimental values:

Triplet: H-C-H angle of 134.24 degrees (lit.1 134), d(C-H) = 1.08272 A (lit. 1.0753 A)

Singlet: H-C-H angle of 101.79 degrees (lit. 102), d(C-H) = 1.12770 A (lit. 1.107 A)

The triplet methylene is more stable than the singlet by 0.02981066 a.u. or 78.27 kJ/mol. The computations assign both geometries C2v symmetry. The triplet took 19 seconds to compute, the singlet 17 seconds. It is evident that the fast computations give rather good agreement with the experimentally determined geometrical parameters of the methylenes.

These two structures were optimized in order to see whether the programme give reasonable results at the most basic level. The energy of the triplet carbene is predicted to be lower than that of the singlet carbene, which is in agreement with experiment.

The FMOs of both singlet and triplet methylene were briefly looked at. For the singlet, the LUMO had essentially the shape of a p orbital with lobes above and below the H-C-H plane and the HOMO contained the lone pair. The triplet FMOs looked very similar, the only difference is of course the occupancy.

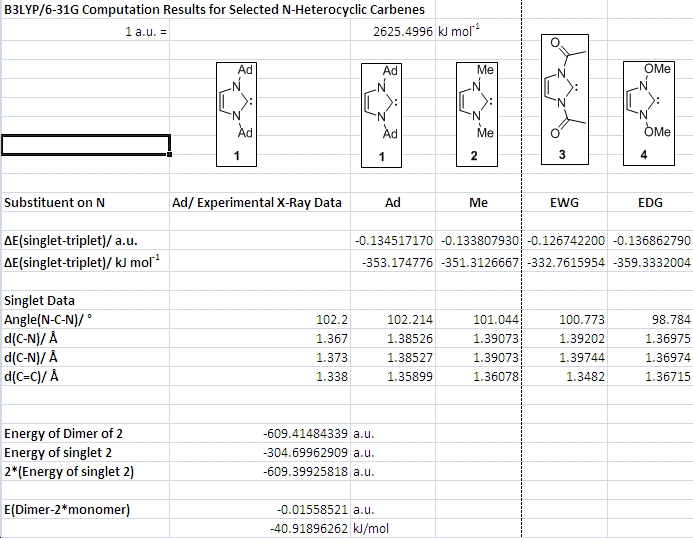

The next step was to move on to an analogue of the first carbene the solid state structure of which had been reported by Arduengo in 1991 (1,3-diadamantyl derivative of imidazol-2-ylidene, 1, shown in table below)2. The computational cost of the Ad groups is huge, so in the analogue used they were replaced by the simplest aliphatic substituent, Me. A very interesting property of these N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) is that the singlet state is more stable than the triplet state. The origin of this will be discussed later on. The computational study at hand aims to confirm the experimental observation and find out how much more stable the singlet state is.

D-Space links for 1 to 6:

Singlet 1: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1269

Triplet 1: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1268

Singlet 2: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1262

Triplet 2: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1263

Singlet 3: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1264

Triplet 3: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1265

Singlet 4: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1266

Triplet 4: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1267

Singlet 5: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1270

Singlet 6: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1271

The computational procedure for singlet 1, 2, 3 and 4 was as follows:

1) Pre-optimization at the HF/3-21G level on the laptop

2) Full optimization at the B3LYP/6-31G level including NBO analysis on the SCAN

The same procedure was intended for triplet 1. However, after the pre-optimization step, an unexpected geometry was obtained. I would have expected a structure with the C=C double bond intact and the two unpaired spins on the carbene carbon atom. The geometry of the structure is shown in the jmol file below. From the Mulliken spin densities quoted in the log file, it appears that Gaussian finds as the most stable structure one that has pronounced diradical character.

In order to make sure that the computed structure for the triplet was reasonable, a B3LYP/3-21G optimization was carried out. This gave essentially the same geometry. Thus, for triplet 1:

1) Pre-optimization at the HF/3-21G level on the laptop

2) 2nd Pre-optimization at the B3LYP/3-21G level on the laptop

3) Full optimization at the B3LYP/6-31G level including NBO analysis on the SCAN

Both fully optimized geometries are shown as 3D rotatable models in Jmol below. If the geometry of singlet 2 (i.e. bond angles and bond lengths) agrees with the one determined experimentally by x-ray diffraction of the Ad substituted NHC, then we can consider the computed electronic structure to be reasonably reliable. Looking at the molecular orbitals and NBO analysis will give some clues to the bonding and reactivity of this molecule.

3D view of the optimized singlet MeNHC

|

|---|

The geometry of singlet 1 had to be optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G level twice. After 342 cycles and 3 days and nine hours of computation, the job was terminated automatically because no convergence of the displacement could be achieved (see output file). By contrast, the triplet had about six hours of cpu time. Generous help in the analysis of the output file by Dr Patricia Hunt then showed (by animating the progression of the intermediate geometries) that the geometry was almost optimized and that the computer was oscillating slightly around some ideal value. The output geometry was submitted again and after 40 minutes the geometry was finally optimized.

The table presents the computed energy differences between singlet and triplet carbenes. In all cases the singlet is more than 300 kJ/mol more stable than the triplet. These results agree with experiment in that only singlet states are observed for these NHCs. The reason for this huge energy difference lies in three effects brought about by the nitrogen atoms. First, there is a negative inductive effect due to nitrogen's relatively high electronegativity which lowers the energy of the sigma orbital containing the lone pair on the carbon atom. Second, the nitrogen atoms are able to resonantly donate electron density (their lone pairs) into the formally empty p-orbital on the carbene C. Finally, the NHCs 1 to 4 can all be envisaged to have some degree of aromaticity. It was initially thought that this aromaticity provided the main contribution to the stability of NHCs. However, when Arduengo succeeded in isolating an NHC without a C=C double bond in the five-membered ring in 19923, this theory had to be abandonded. It may well be that it contributes to the stability of NHCs, but it is not a strictly necessary condition for isolating them.

Arduengo, A. J. et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117, 0000, DOI:

The table also shows the experimentally determined parameters of The Di-Adamantyl substituted NHC along with the computational predictions for 1, 2, 3 and 4. The general agreement of values is good. There are no completely off-the-wall values for bond angles and bond lengths that would suggest a failed optimization. Furthermore, the very bulky carbene Arduengo synthesized in order to be able to form good crystals will have slightly different values for bond lengths due to packing effects that occur in the crystal – the computation does not model these.

Comparing the geometries of 2, 3 and 4 is instructive. With an EWG attached to both N instead of a simple Me, the energy difference between triplet and singlet becomes less, i.e. the singlet is destabilized relative to the triplet. Moreover, the C-N bond length is increased very slightly. Both suggest a weakening of delocalization of the N lone pairs into the empty orbital on the carbene carbon atom. It appears that a simple carbonyl group is not electron withdrawing enough to illustrate the point in terms of bond lengths. Maybe a trinitro-substituted phenyl ring attached to both N would give more unambiguous results, but there is not enough time for the associated computations. In any case, putting an electron releasing or electron donating methoxy group on the nitrogen atoms has the expected opposite effect! The C-N bond lengths from nitrogen to the carbene carbon atom become significantly shorter (about 0.02 A), the N-C-N angle more acute (98 vs 101 degrees for Me) and the singlet-triplet gap becomes larger. These results suggest that increasing the N atoms’ ability to resonantly donate electron density through overlap of the p-orbitals on N and the carbene C will stabilize the carbene.

In conclusion, through these simple computations results were obtained that strongly support the idea that the mechanism by which N-heterocyclic carbenes are stabilized is the one described above.

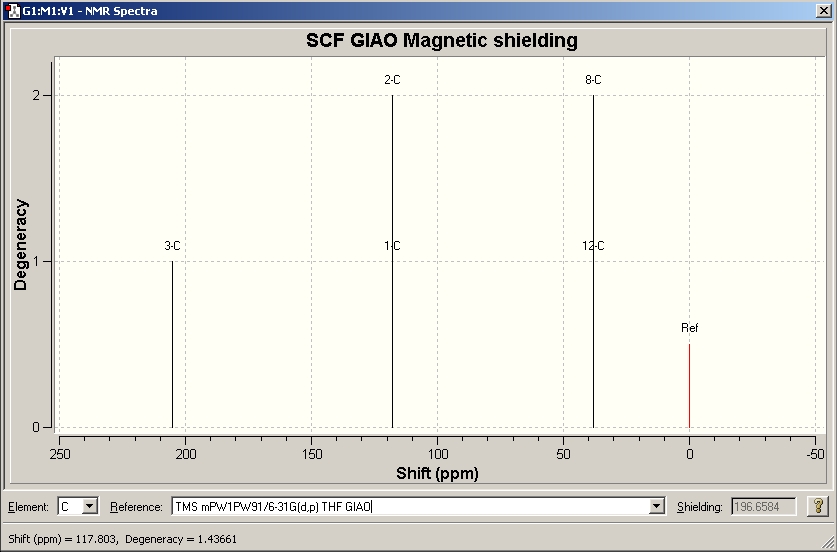

We will now look at whether we can detect some of the tell-tale signs of aromaticity. The 13C NMR spectrum of 2 was predicted using the GIAO approach introduced in the organic module. For one thing, it will be interesting to see how well this compares to the experimentally recorded one for the Ad substituted NHC 1. Also, maybe the two alkene carbons can be seen to be shifted more towards the aromatic rather than the alkene region of the spectrum.

The procedure was as follows:

1) Optimize the geometry using the follow entry in the command line:

- mpw1pw91/6-31g(d,p) opt(maxcycle=25)

i.e. the DFT method MPW1PW91 using a 6-31G (d,p) basis set.

2) Submit the optimized geometry for NMR shift calculation

- mpw1pw91/6-31g(d,p) NMR scrf(cpcm,solvent=tetrahydrofuran)

In order to predict the shifts correctly, the reference TMS in tetrahydrofuran was needed. This was not present in the dropdown menu, so the geometry of TMS was optimized at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level and then its NMR spectrum in THF predicted using the same GIAO method. Professor Henry Rzepa kindly implemented the new "TMS in THF" reference into the dropdown menu so that the work could proceed.

Apart from assessing the aromaticity of the five-membered ring, it should also be possible to comment on exactly how much of a carbene the NHC actually is. What do I mean by this? The massive electronic stabilization of the singlet state of 2 that makes it possible to actually store it (albeit in THF solution, not neat) at -30 degrees Celsius for several days could be said to alter the electronic structure of the "carbene" so much that one is actually only dealing with a carbene-like molecule. This trade-off between making a highly unstable species persist long enough to characterize it and changing the electronic structure of what is being observed significantly is a common theme in carbene chemistry or indeed in any effort dealing with characterizing highly unstable species in inorganic main group chemistry. The shift of the NHC carbene compared to that of free singlet methylene will hopefully give information to answer this question.

The image below shows a snapshot of the predicted NMR spectrum of 2 using the GIAO method.

D-Space link for NMR Prediction: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1273

The general agreement between literature and computation is good. The methyl groups on N and the two alkene carbons agree very well. Both exhibit shifts that are reasonable, the Me is shifted downfield a bit due to the electronegative nitrogen atom, and the alkene carbons have shifts typical for olefinic or aromatic double bonds. This, unfortunately, makes it difficult to get an idea of the degree of aromaticity by looking at the 13C shifts of those two carbons. The carbene carbon deviates by 10 ppm and the relative error is thus about 5%. This is not as good as the other two signals, but given the unusual electronic structure of the carbenic carbon this can probably be excused. The chemical shifts of carbenes usually fall in the range 200 - 300 ppm (i.e. very deshielded due to electron deficiency) and thus show the same kind of behaviour as carbocations characterized in superacid media. The fact that carbene 2 with a shift of 215 ppm is at the lower end of possible shifts for carbenes suggests that its electron deficiency is partly relieved.

Furthermore, we will look at all the MOs of 2 to see whether there are any that are clearly delocalized over the relevant five atoms and are an all-in-phase or all-bonding combination. This is also a well-known concept of aromaticity.

3D view of dimer of carbene 2

DimerofCompound2 |

The geometry of the alkene resulting from dimerization of singlet 2 was optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G level as well. As presented in the table, the energy of the dimer is approximately 40 kJ/mol lower than that of two isolated molecules of 2. This raises an interesting question. The carbene is obviously unstable, but how unstable? The experimental observation is that a THF solution of 2 can be stored for several days at -30 degrees Celsius. As a neat liquid (i.e. in very concentrated "solution"), it decomposes quickly. The low temperature thus makes 2 persistent and kinetically prevents the decomposition or dimerization pathway from being taken; the low temperature deprives the surroundings of the necessary activation energy. Furthermore, the donor solvent THF might have a stabilizing effect on the carbene.

A note on the side: The optimized geometry of 2 shown above is quite interesting. Clearly, the alkene is not flat - in fact, the N-C=C-N dihedral angle is about 21.6 degrees, when ideally it should of course be zero. If the steric repulsion between two pairs of methyl groups already forces the alkene Pi system to give up some of its p-p overlap in order to accommodate the substituents on nitrogen, then two pairs of adamantyl groups can reasonably be expected to prevent the formation of the alkene (dimerization of 1) altogether. This finding also explains why no dimer at all could be found by Arduengo upone decomposition of 2: There are other reaction pathways (with e.g. oxygen) that are lower in energy than the high activation energy pathway of forming the strained alkene.

D-Space link for Dimer of 2: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1272

It would be interesting to see whether computational studies of the dimer of 1 would predict it to be more stable than two monomers. This is probably the case. The experimentally observed stability thus probably reflects (in part) the kinetic stabilization by the very bulky adamantyl groups. However, it would take too long to optimize the geometry of a compound with four Ad groups.

The HOMOs and LUMOs of singlet 2, 3 and 4 were then visualized. The results are very interesting. The shape of the HOMO comes out as expected, in the sense that for all three molecules it has a large sigma lobe pointing away from the carbene carbon in the plane of the five-membered ring. This is in line with the behaviour of NHCs as nucleophiles and very strong sigma-donors in transition metal complexes4.

The shape of the LUMO is striking. For singlet 2, there appears to be no orbital coefficient at all on the carbene carbon atom! Assuming that the LUMO is the orbital that governs a molecule’s behaviour as an electrophile, this offers an explanation for the fact that the electrophilicity of NHCs is effectively removed or at least diminished to such an extent that only reactions with the carbene as nucleophile are observed. If at all, electrophilic reactivity of 2 will be observed in a different part of the molecule, e.g. the C=C double bond. Singlet 3, with electron withdrawing carbonyl groups on both nitrogen atoms, has an interesting feature – its LUMO does feature a significant coefficient on the carbene carbon atom. This result can be interpreted such that an appropriately substituted NHC will, under the right conditions, react as an electrophile.

The last two MOs shown are MOs no. 16 and 23 of compound 2. They are included here because they are the two bonding molecular orbitals which fulfil the criterion of aromaticity. They are Pi-type (as indicated by the opposite signs of the lobes on either side of the ring) and delocalized across (at least) the five ring carbon atoms, which all formally have a p type atomic orbital on them. This result suggests that aromaticity does indeed play a role in stabilizing the NHC.

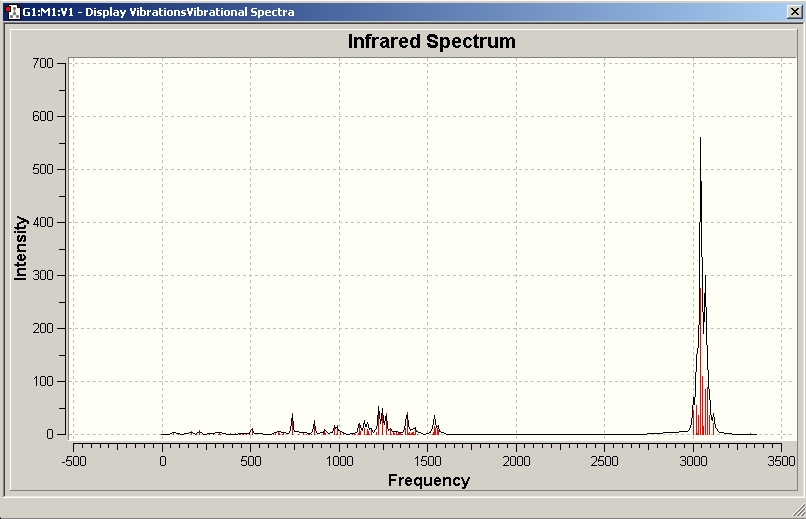

A job was submitted to the SCAN for vibrational frequency calculation of singlet 1.

D-Space for Frequency Computation: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-1261

In the B3LYP method, stretching frequencies are overestimated systematically. With an appropriate correction, this error can thus be removed and predicted frequencies can be compared to experimentally recorded IR spectra.

Arduengo himself found the following IR stretches: 2920, 1504, 1448, 1378, 1350, 1303, 1213, 1291, 833, 695, and 495

The above image shows the predicted IR spectrum for singlet 1. The problem is that the alkene has a predicted frequency of 1614, but an intensity of zero, i.e. its vibration does not result in a change in dipole moment. Thus, the most telltale functional group cannot be analyzed in this example.

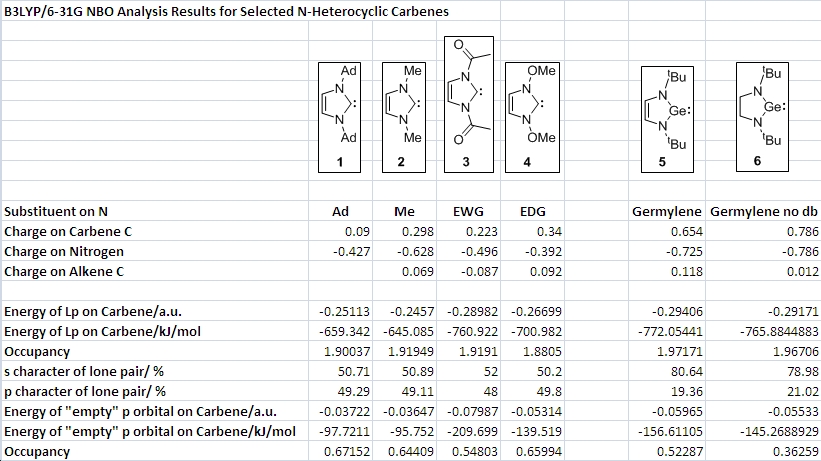

To complement and contrast the studies carried out on carbenes, electronically similar molecules of heavier main group elements were investigated, specifically the germylenes 5 and 6 (for structures, see table below), which were synthesized in 1992 by Hermann et al.5 Dr Hunt kindly provided instructions on which basis set to choose and how to include the appropriate code in the Gaussian input file. These instructions, along with some explanations, are given in the following section.

What does the “Gen” keyword do (Information adapted from the Gaussian 03 Manual)?

The Gaussian programme has stored certain number of very common standard basis sets (such as 3-21G, 6-31G, etc). For some calculations, these are not entirely appropriate, so the Gen command allows the user to employ a basis set specified by themselves. To read the specific basis set into the input file, the space normally reserved for the basis set (i.e. after the method - # b3lyp xxx) is simply filled with gen.

The keyword pseudo commands Gaussian to use an effective core potential for the core electrons. Many standard pseudo potentials are available (CEP, CHF, LANL1, LANL2, LP-31 etc), but if used just like that they will apply to all atoms. For the germylene, we only want the ECP to be applied to the heavy Ge atom, not to the computationally inexpensive carbons and nitrogens.

The sequence gen pseudo = read can then be employed to tell Gaussian to use a general basis set with an effective core potential (ECP, or pseudo potential) for only a single atom. Both germylenes were pre-optimized at the HF/3-21G level, and then optimized with the command line of the input file looking like this:

- opt b3lyp/gen pseudo=read gfinput int=ultrafine scf=conver=9 geom=connectivity pop=nbo

and an extra bit at the end defining which basis sets to use for which atoms, and which pseudo potential to use:

(Blank line)

Ge 0

LANL2DZ

C N H 0

6-311g(d,p)

(Blank line)

Ge 0

LANL2DZ

(Blank Line)

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The results of the NBO (Natural Bond Orbital) analysis of the carbenes and germylenes are very interesting, i.e. they cannot be rationalized in a trivial way.

The positive charge on the carbene carbon is decreased with an EWG and increased with the electron donating methoxy group. This suggests that the dominating factor in calculating charges is NOT Pi delocalization – otherwise the electron donation of the OMe group would cause a very low positive charge on the carbene C. This leads to the conclusion that the electronegativity of oxygen and thus inductive withdrawal of electron density cause the higher positive charge on C in 4. A way to check this would be to replace oxygen with sulphur, which is less electronegative but still electron donating, but there was too little time.

The energy of the lone pair on carbon can also be explained by inductive effects. Since the lone pair is orthogonal to the Pi system, Pi overlap effects are not at work anyway. The inductively electron withdrawing OMe and amide groups (which is also resonantly withdrawing, but this does not matter here) both stabilize the lone pair orbital. In this respect, 2 can be expected to be the most nucleophilic carbene with the highest energy HOMO (“only” -645 kJ/mol as opposed to -700 for the others).

The occupancy stays roughly the same across the four carbenes, around 1.90 electrons in the lone pair orbital. It is approximately an sp hybrid, with 50% s and 50% p character.

The other orbital of interest is of course the formally “empty” p-orbital on the carbene carbon. The occupancies indicate that it is not, in fact, empty, which is in line with the argument presented above about the Pi donation into the empty orbital in order to achieve stabilization. For 3, the electron withdrawing carbonyl groups tie up the N lone pairs in resonance and thus they are less able to donate onto the carbene, this results in an occupancy lower than for 1, 2 and 4, which all feature electron donating groups. It is interesting to note that the LUMO in 3 has an energy of -0.07987 a.u., much lower than in the other carbenes. We can thus expect this carbon atom to be the better electrophile, which agrees with what was found earlier – the fact that in 3, the LUMO actually has a coefficient on the carbene C and might thus be expected to behave as an electrophile.

The germylenes have a much high positive charge on the germanium atom than the carbenes do on the corresponding carbons, and a more negative charge on the nitrogens. This is probably due to the larger difference in electronegativity between N and Ge, leading to more charge separation. The occupancies of the lone pair orbitals are about 1.97, i.e. very close to the ideal 2. For both germylenes, the lone pair has a much higher s character (80%) and only 20% p-character. This follows the expected trend; as we go down a group towards the heavier elements, the inert pair effect starts to kick in with the resulting unwillingness of s-orbitals to participate in hybridization.

There is one more result which deserves attention. The electron density in the “empty” 4p orbital on Ge is 0.52 for Ge with double bond, and 0.36 for Ge without double bond. Both have the same nitrogen substituents donating electron density, so the difference must be due to the presence of the alkene Pi system. This result can be interpreted tentatively as evidence for aromatic delocalization of electrons around the five membered ring in the germylene containing a C=C double bond – The cyclic array of adjacent p-orbitals even allows the alkene to participate in the stabilization of the electronic situation at Ge. In this case, the partial aromaticity is very likely the reason for the observation that the first germylene is stable in air for short periods of time, whereas the one without C=C decomposes instantaneously on exposure to air.

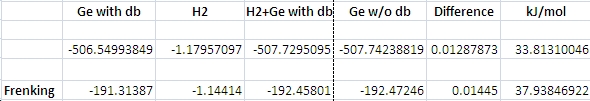

The table below shows the calculation of the heat of hydrogenation of 5 to give 6. Initially I had hoped to see a result that would indicate the sum of molecular hydrogen and 5 being more stable than 6, and thus reflect some aromatic stability. In retrospect, this expectation does not make much sense. As can be seen from the table, the calculated heat of hydrogenation is about 30 kJ/mol (i.e. hydrogenation is exothermic), in reasonably good agreement with much more accurate computations carried out by Frenking and Boehme6. Even the hydrogenation of an aromatic system such as benzene is exothermic, and simply by comparing stability of benzene plus three molecules of hydrogen and cyclohexane will not give any information as to the aromaticity of the system.

The frontier molecular orbitals of 5 and 6 are presented in the table below. They differ with respect to those of the carbenes in two important ways. First, the HOMO in 5 no longer appears to be a sigma type orbital. There are clearly two lobes of opposing phases above and below the plane of the ring, indicative of Pi character. Second, the HOMO in 6 has a very small sigma type lobe pointing away from Ge. This suggests that the molecules will have very different reactivity and coordination behaviour to metals, if it is possible to form a coordinative bond at all. In contrast to the carbenes, the LUMOs have pronounced coefficients on the germanium atom, so these compounds should exhibit carbene-like reactivity as an electrophile, particularly as the NBO charges (as presented above in the table) are large and positive (around +0.6), which is much more than for the carbenes. Thus, for the germylenes, a combination of a more stable LUMO, more positive charge on Ge (electrostatic attraction of nucleophiles) and a large coefficient on Ge in the LUMO (nucleophilic HOMO can overlap with lobes on Ge) all suggest that electrophilic behaviour can be expected.

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

References Mini Project

1. A. Neugebauer, G. Häfelinger, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2005, 6, 157

2. Arduengo, A. J. et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 361

3. A. J. Arduengo et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1992, 114, 5530-5534

4. W. A. Herrmann, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2002, 41, 1290

5. W. A. Herrmann et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 1992, 31, 1485

6. G. Frenking, C. Boehme, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1996, 118, 2039-2046