Rep:Mod:cdhxp74296

Part 1: An Introduction to Gaussian: BH3 and TlBr3

As an introduction to using Computational methods to study structure, reactivity and spectroscopy of chemical system, we are first going to look at the application of these methods on two simple systems, Borane, of which we are very familiar, and TlBr3, which is new to us, but as we shall see, we are able to draw parallels to what we are more familiar with.

BH3

Borane is a familiar molecule, one which we came across when learning the application of group theory to the molecular orbitals of chemical systems. We are going to construct and run a calculation to optimise the structure of this simple molecule then look at the MO's, NBO's and vibrations, and compare the calculated results to our group theory predictions.

Optimisation

Using the Gaussview 3.09 GUI, a molecule of borane, BH3, was created, using the trigonal planar boron fragment. We then defined a bond length using the 'Modify bond length' control of the interface, and set all three B-H bonds equal to 1.5Å; this is a longer bond than that reported, but it enables us to see the effect of the optimisation directly. Also, this tool would be very useful for defining a geometry from a crystal structure. We then ran a geometry optimisation calculation on the molecule, using a DFT/B3LYP/3-21G method, route and basis set respectively. This is a low level basis, but this means the calculation can be run on the laptops.

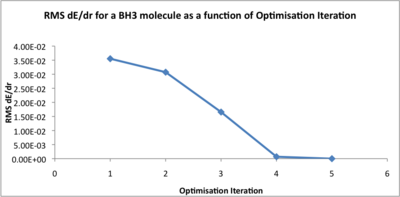

How does the optimisation work? Gaussian calculates the energy of the molecule based upon the molecular geometry defined, by numerically solving the Schrodinger equation, then changes the positions of the nuclei, to try to reduce the energy. This iterative cycle continues until a minimum in the energy is reached. This is when the gradient of the dE/dr plot converges under a set value, close to zero. We can view the geometry on each iteration, to see how the structure of the molecule changes as the energy is lowered, and plot the total energy and RMS dE/dr as a function of iteration, to show this procedure in action.

|

BH3 Geometry Optimisation - Iterative Sequence |

|||||

|

Step no |

Step 1 |

Step 2 |

Step 3 |

Step 4 |

Step 5 |

|

Geometry |

|||||

|

Total Energy /Hartrees |

-26.38 |

-26.42 |

-26.45 |

-26.46 |

-26.46 |

|

RMS dE/dr |

3.55E-02 |

3.07E-02 |

1.66E-02 |

6.91E-04 |

2.85E-06 |

|

B-H Bond Length /Å |

1.50 |

1.41 |

1.28 |

1.19 |

1.19 |

In this simple case, we can directly relate the decrease in energy to the length of the B-H bonds, all of which are equal. As the bond becomes shorted, the overlap integral between the H3 SAO's and the B AO's will increase, so the total energy will become more negative. However, at the same time we are pushing the nuclei and electrons together, so this total energy will continue to decrease until the nuclear/nuclear and electron/electron repulsive terms of the Hamiltonian for the system balance this attraction. Therefore, the BH bond distance is determined by a balance of attractive nuclear/electron interaction, and repulsive electron/electron and nuclear/nuclear interactions. For more complex molecules, this principle still stands, but the computation will take much longer, as more atomic pair terms have to be calculated.

The optimised BH bond angles were all 120o exactly, as expected, and the bond lengths 1.19Å. The molecule is D3h symmetric, so necessarily all bond length and angles are the same. Comparing to literature, we find a reported bond length of 1.2325Å[1], recorded by UV. This is a good result for our low basis.

BH3 Optimised Geometry |

Molecular Orbitals

We can construct a qualitative MO diagram for BH3, from the symmetry allowed combination of H3 SAO's and B AO's. Gaussian calculates the LCAO for the MOs. We shall compare between the qualitative form and the actual form of the MOs, to judge the validity of out qualitative LCAO approach. Calculation to the DFT/B3LYP/3-21G level, orbitals shown at isovalue 0.02. Rendered using Avagadro 1.01.

|

BH3 valence molecular orbital diagram |

|

|

3a1' |

|

|

2e' |

|

|

1a2" |

|

|

1e' |

|

|

2a1' |

|

|

1a1' |

|

The molecule is of the D3h point group, so we use H3 symmetry fragments to build the diagram, since these are of the same point group. The B 2s (and 1s) AO's and H3 totally bonding SAO are both of a1' symmetry, and form a symmetry allowed combination to make a totally bonding MO, 1a1', and its antibonding counterpart, by reversal of the phase of one component basis set. These are s-s overlaps, and quite close in energy, so are strongly bonding and antibonding. The degenerate e' H3 SAO set can form allowed overlap with px and py B AO's. This p-s sigma overlap is less strong than s-s, and the two fragment orbitals are further apart in energy, so are split less than the a1' combination. The pz AO is of a2" symmetry, which has no symmetry partner on the H3 fragment, so remains non-bonding. There is no significant mixing expected in this molecule, because the 2a1'and 1a1' are both filled and too far apart in energy.

Comparing the two sets, we see good agreement between our simple LCAO diagram and the computed MO's. The order of the MOs as we predicted is the same, and the form too. Therefore, we can say that, at least for simple molecules, out qualitative group theory prediction holds true, and is a very useful tool.

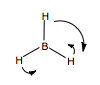

Natural bond orbitals

The calculation to generate the molecular orbitals of the BH3 molecule was specified to also carry out a full population analysis, and calculate the NBO's. We now look at the results.

First, we analyse the atomic partial charges. The molecule is overall neutral, so the calculation reports the charge relative to that overall charge. Hence, we find each hydrogen atom has a partial negative charge of -0.11, and the central B atom has a partial postive charge of +0.33, i.e summing to zero. The B atom has this partial positive charge because it has an empty pz orbital - the non-bonding a2" MO we discussed above. This means the BH3 molecule is a Lewis acid, since the B atom is electron deficient.

We can also read off the hybridisation of each bond. All three B-H bonds are of equal length, and are all of sp2 hybridised B (1s and 2p) and 1s H. Therefore, as we expect from the MO analysis, and the Lewis acidity, we can conclude that the B centre has an empty pz orbital, explaining the planar structure and three bond angles of 120o. The NBO picture of the molecule is shown.

If we look at the Second order Perturbation Theory analysis section, we can see if there is any secondary orbital overlap which acts to stabilise the system. As expected, there is no significant secondary orbital overlap in our molecule - normally we would expect Secondary overlap in systems with high energy donors and low energy acceptors, such as lone pairs and π* orbitals, given a correct orientation, but here we have no good donors or acceptors.

Vibrations

When we discussed the optimisation, we said that the dE/dr = 0 at our optimal geometry. This is not the only point at which this is true. This condition is also fulfilled at a transition state. Obviously, a transition state will, by definition, not be the ground state molecular geometry, so we must check that we have found ground state minimum, and not the transition state, by performing a frequency analysis. The frequency calculation finds the second derivative of position, with respect to energy, i.e the curvature of the slopes either side of the stationary point. If the curvature is negative, we have found a maximum - a transition state of addle point, and if positive, then we have found the ground state geometry.

A DFT/B3LYP/3-21G BH3 frequency calculation was carried out on the geometry resulting from the optimisation. Reading from the log file, we look at the low frequencies section, corresponding to the translational and rotational modes ('-6' in 3N-6), the only negative frequencies are -0.6560, -0.0170 and -0.0021cm-1. These ideally should be zero, but given our low level basis, this is a good result, and we can be confident we have indeed found the minimum.

Also reading from the low frequencies output, we find the highest frequency translational/rotational displacement is 22cm-1. The lowest energy mode of a true vibration of the molecule, is 1146cm-1. This is almost two orders of magnitude smaller, which is again a check to us that the optimisation worked. This shows it is OK.

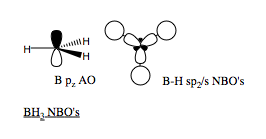

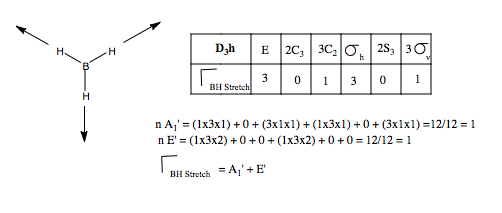

We are now going to predict the number and form of the vibrational modes of BH3, from group theory, much as we did for the molecular orbitals above. First, we need to form a basis set, comprising of displacement vectors describing the vibrations, and see how these transform under the symmetry operations of the point group. This gives us the reducible representation. Then we find the contributing irreducible representations using the reduction formula. Finally, we find the form of the vibration, and whether or not they are IR active, using the projection operator, or in a simple system like this, guess.

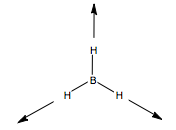

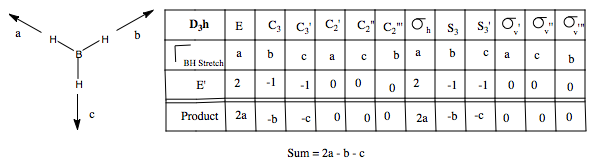

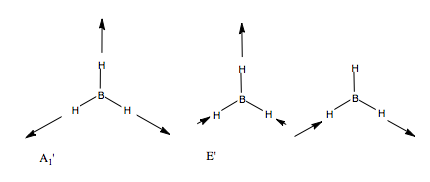

Let us first apply this to the stretching modes of the molecule. We apply a displacement vector to each B-H bond, and form our basis. We form the reducible representation of this basis, and using the reduction formula, find the component irreducible representations. We therefore predict three BH stretching modes, a non-degenerate mode, and a pair of degenerate modes. What do these look like? We can form a guess for the A1' mode, because it is of the highest symmetry, it will be the totally symmetric, all BH stretches, in phase with one another. The form of the degenerate pair is not so simple. We use the projection operator. Once again, we form our basis, and take one vector, and see how it transforms onto others under the symmetry operations. We treat each operation individually. We then multiply each character by the irreducible representation of E' symmetry, and this gives us the coefficients for each of the three vectors, but only for one of the two degenerate modes. The other we find by guessing.

We could guess using orthogonality, but there is an easier way. When determining the form of H3 SAOs, we treated a 3H1s AO basis and found a totally symmetry a1' orbital and a degenerate e' set. The orbitals before and the vibrational vectors now move in the same way under the point group, hence we expect the same form of the objects. Hence, we can form a guess for the second E' mode by reference to the second H3 e' orbital, namely phi = s2-s3, and in the case of vibrations, e'(b) = vector b - vector c. The form of our three guesses are shown:

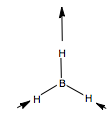

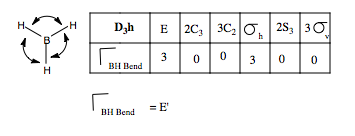

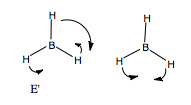

We can carry out the same analysis for bending modes. This time, we place curved vectors between the bonds, allowing the bonds to rock back and form in plane These we would expect to be at a lower frequency than the stretching modes. We form the reducible representation, and find the contributing irreducible representations. Only one doubly degenerate mode contributes to the in place BH bending. Using the logic we used above, we can guess the form of the vibrations by reference to the H3 SAO e' orbital set. Thus, we form our guess:

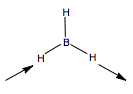

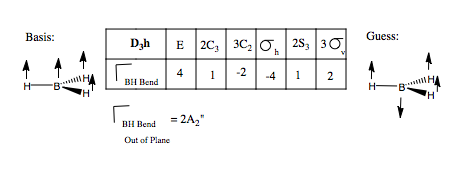

Finally, we have to consider BH out of plane bending. Again, forming the basis, by placing arrows across pointing out of the plane of the molecule, we form the reducible representation of this basis, and use the reduction formula to find the contributing irreducible representations. We find two, non-degenerate A2" modes. However, we have to be careful here, as one mode corresponds to pure translation in the z-direction, as can be seen in the character table. Hence, we expect one A2" true vibrational mode. If we make an educated guess as to the form of the vibration, we may suggest that the three H atoms displace one way, and the B atom the other way. This vibration is not pure translation down the z-axis, and all atoms displace, as allowed by the basis. This out of plane bending we would expect to again be lower in energy than the in plane bending modes.

The condition for a vibrational mode to be infra red active is that on transition, the dipole moment of the molecule must change. Hence, we would expect all modes expect A1' to be IR active, since only this one is totally symmetric and doesn't change the dipole moment.

|

Comparing the predicted and calculated vibrational modes of borane |

||||||||

|

Symmetry |

Prediction |

Calculated |

||||||

|

Form |

Active? |

Displacement |

Frequency |

Intensity |

||||

|

A1' |

Inactive |

|

2593 |

0 |

||||

|

E' |

IR Active |

|

2731 |

104 |

||||

|

E' |

IR Active |

|

2731 |

104 |

||||

|

E' |

IR Active |

|

1204 |

12 |

||||

|

E' |

IR Active |

|

1204 |

12 |

||||

|

A2" |

IR Active |

|

1146 |

93 |

||||

We find our predictions agree well to those calculated, in terms of the number, form, the activity and the order of energy. We can compare the three optically allowed frequencies to literature[2]. The A2" mode is calculated to resonate at a frequency of 1145cm-1, and is reported at 1125cm-1. The E' double degenerate modes are calculated to resonate at 1205cm-1 and 2731cm-1, and are reported at 1640cm-1 and 2808cm-1. We find good agreement for two sets of vibrational modes, but one prediction gets the energy totally wrong. How can this be? The energy order is still correct, but the magnitude is off. This corresponds to the in plane BH bending modes. The prediction underestimates the energy to excite the resonance of the modes. Perhaps this is due to the difference between gas-phase (modeled) and real, solvated BH3. Or this could be due to the dimer, B2H6, but the literature reports this as BH3, measured by experiment. Unfortunately there is not any indication of how this was collected, so we cannot be sure why this is different.

TlBr3

Optimisation using a Pseudopotential basis set

Using Gaussview, a molecule of TlBr3 was created, using a trigonal planar Tl fragment, and attaching to it three Br atomic fragments. The symmetry of the molecule was confined to the D3h point group. The geometry of the molecule was optimised, using a DFT B3LYP/LanL2DZ method/route/basis set calculation. This basis set uses a pseudopotential to describe the heavier elements beyond the first row, since their chemical behavior is determined by the valence electrons anyway. Without the use of the pseudopotential, the calculation would likely take a very long time to solve all for of the electrons in the four heavy elements.

The calculation completed in three iterations - the RMS gradient converged under its predetermined value (close to zero). As for BH3 above, we can see that the Tl-Br bond distance determines the geometry and hence energy of the molecule; again a balance between electron/electron and nuclear/nuclear repulsions and electron/nuclear attractions. The optimised geometry has Br-Tl-Br bond angles all exactly of 120.0o - we confined to D3h, so this is to be expected, both in terms of the symmetry and the energy of the molecule - any closer angle would make the repulsion between the close two more than between the further two, and this makes no sense considering the three atoms are identical. The bond lengths are calculated to be 2.65Å, again, all the same length. Bonds lengths in a gaseous sample of TlBr were measure using microwave spectroscopy and found to be 2.6182Å[3]. Given that we are dealing with Tl, with its valence 6s2 6p1 electronic configuration, we would expect an inert pair effect for the 6s electrons, explaining why the Tl is mono-valent, and this also would account for the difference in bond length. Given this, our calculation is in good agreement, also considering the use of a mid-level pseudopotential basis set.

BH3 Optimised Geometry |

Vibrations

An analysis of the vibrational frequencies was carried out, to check the optimisation had minimized onto a conformation, and not onto a transition state. We must do this for every optimisation. A DFT B3LYP/LanL2DZ frequency calculation was carried out. This is the same method/route and basis set as the geometry optimisation, otherwise the results would be invalid. Why? If we consider a basis set like taking a photograph - aka, a photograph reproduces fairly accurately the real scene, a high level basis set if you like. However, if we then made a drawing of this photograph, i.e use a lower basis set for a further calculation, we loose information along the way between the photo and the drawing - in the quantum computing case we loose accuracy in the result. If we did it the other way around, we now have a photo of a drawing - again, the accuracy has suffered when we compare to the real scene. In this case we can say there is no point undertaking a calculation using a higher level basis set on a geometry optimised by a low level basis set - the accuracy is limited by the lowest level basis set. Of the '6' vibrational modes corresponding to pure translation and rotation, there was a frequency at -3cm-1 and one at 4cm-1. These should ideally be zero as we have said. However, they are an order of magnitude smaller than the lowest energy real mode. The use of pseudopotentials may also contribute to these not being equal to zero. The negative frequency was still within limits to where we can say the optimisation worked.

The nature of the displacements are identical to those of BH3 above, a necessary condition since vibrational modes are only observed if the displacement conforms to the symmetry of the point group. Since the molecules are in the same point group, D3h, they have the same symmetry allowed modes. We can in-fact use the form of the vibrational modes for any AB3 D3h species. However, the frequency of the resonance of the modes is different. The resonant frequency of a bond is proportional to the inverse square of the reduced mass of the vibrating system. Gaussian also calculates this, which we can read from the log file. The reduced mass of the TlBr3 modes are much larger than those of the BH3 vibrational modes, hence the frequency of vibration is higher. The intensity we see is also weaker for the TlBr stretches. This is because the lower energy mode oscillates slower and is hence less resonant.

|

Comparison between BH3 and TlBr3 vibrational modes |

||||||

|

Mode |

BH3 |

TlBr3 |

||||

|

Frequency /cm-1 |

Intensity |

Reduced Mass /au |

Frequency /cm-1 |

Intensity |

Reduced Mass /au |

|

|

A2" |

1146 |

92 |

1.25 |

52 |

6 |

117.72 |

|

E'(a) |

1204 |

12 |

1.11 |

46 |

4 |

88.46 |

|

A1' |

2593 |

0 |

1.00 |

165 |

0 |

78.92 |

|

E' (b) |

2731 |

103 |

1.13 |

210 |

25 |

101.4 |

Files

Borane DFT B3LYP 3-21G Optimisation: [1]

Borane DFT B3LYP 3-21G Frequency: [2]

Borane DFT B3LYP 3-21G SCF MO/NBO: [3]

TlBr3 DFT B3LYP LanL2DZ Opt and Freq: [4]

General references made throughout to:

T.Hunt, Molecular Orbitals in Inorganic Chemistry Lecture Course, 2009-2010

K.C.Molloy, Group Theory For Chemists, 2007

J.B.Foresman and A.Frisch, Exploring Chemistry with Electronic Structure Methods, 1996

Part 1: Introduction to the Course: BH3 and TlBr3